Adolf Hitler: Difference between revisions

→Rise to power: simplify mark-up |

Danielc192 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 455: | Line 455: | ||

* [[Streets named after Adolf Hitler]] |

* [[Streets named after Adolf Hitler]] |

||

* [[Vorbunker]] |

* [[Vorbunker]] |

||

* [[Hitler Has Only Got One Ball]] - A comedic song |

|||

==Footnotes== |

==Footnotes== |

||

Revision as of 22:44, 30 August 2012

Adolf Hitler | |

|---|---|

Hitler in 1937 | |

| Führer of Germany | |

| In office 2 August 1934 – 30 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Paul von Hindenburg (as President) |

| Succeeded by | Karl Dönitz (as President) |

| Chancellor of Germany | |

| In office 30 January 1933 – 30 April 1945 | |

| President | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Deputy |

|

| Preceded by | Kurt von Schleicher |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Goebbels |

| Reichsstatthalter of Prussia | |

| In office 30 January 1933 – 30 January 1935 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 April 1889 Braunau am Inn, Austria–Hungary |

| Died | 30 April 1945 (aged 56) Berlin, Germany |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Nationality |

|

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (1921–1945) |

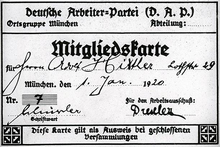

| Other political affiliations | German Workers' Party (1920–1921) |

| Spouse(s) | Eva Braun (29–30 April 1945) |

| Occupation | Politician, soldier, artist, writer |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1914–1918 |

| Rank | Gefreiter |

| Unit | 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Adolf Hitler (German: [ˈadɔlf ˈhɪtlɐ] ; 20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945 and dictator of Nazi Germany (as Führer und Reichskanzler) from 1934 to 1945. Hitler was at the centre of the founding of Nazism, the start of World War II, and the Holocaust.

A decorated veteran of World War I, Hitler joined the German Workers' Party, precursor of the Nazi Party, in 1919, and became leader of the NSDAP in 1921. In 1923, he attempted a coup d'état, known as the Beer Hall Putsch, in Munich. The failed coup resulted in Hitler's imprisonment, during which time he wrote his memoir, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). After his release in 1924, Hitler gained popular support by attacking the Treaty of Versailles and promoting Pan-Germanism, antisemitism, and anticommunism with charismatic oratory and Nazi propaganda. After his appointment as chancellor in 1933, he transformed the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, a single-party dictatorship based on the totalitarian and autocratic ideology of Nazism. His aim was to establish a New Order of absolute Nazi German hegemony in continental Europe.

Hitler's foreign and domestic policies had the goal of seizing Lebensraum ("living space") for the Germanic people. He directed the rearmament of Germany and the invasion of Poland by the Wehrmacht in September 1939, leading to the outbreak of World War II in Europe. Under Hitler's rule, in 1941 German forces and their European allies occupied most of Europe and North Africa. By 1943, Hitler's military decisions led to escalating defeats. In 1945 the Allied armies successfully invaded Germany. Hitler's supremacist and racially motivated policies resulted in the systematic murder of eleven million people, including an estimated six million Jews.

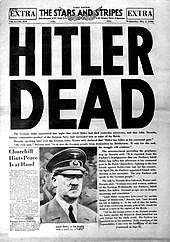

In the final days of the war, during the Battle of Berlin in 1945, Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun. On 30 April 1945, less than two days later, the two committed suicide to avoid capture by the Red Army, and their corpses were burned.

Early years

Ancestry

Hitler's father, Alois Hitler (1837–1903), was the illegitimate child of Maria Anna Schicklgruber. The baptismal register did not show the name of Alois's father, so Alois bore his mother's surname. In 1842 Johann Georg Hiedler married Anna. After she died in 1847 and he in 1856, Alois was brought up in the family of Hiedler's brother, Johann Nepomuk Hiedler.[2] It was not until 1876 that Alois was legitimated and the baptismal register changed by a priest before three witnesses.[3] While awaiting trial at Nuremberg in 1945, Nazi official Hans Frank suggested the existence of letters claiming that Alois' mother was employed as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in Graz and that the family's 19-year-old son, Leopold Frankenberger, had fathered Alois.[4] However, no Frankenberger, Jewish or otherwise, was registered in Graz during that period.[5] Historians doubt the claim that Alois' father was Jewish.[6][7]

At age 39, Alois assumed the surname "Hitler", also spelled as "Hiedler", "Hüttler", or "Huettler". The origin of the name is either "one who lives in a hut" (Standard German Hütte), "shepherd" (Standard German hüten "to guard", English "heed"), or is from the Slavic words Hidlar and Hidlarcek.[8]

Childhood and education

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 at the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in Ranshofen,[9] a village annexed in 1938 to the municipality of Braunau am Inn, Austria-Hungary. He was the fourth of six children to Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl (1860–1907). Adolf's older siblings – Gustav, Ida, and Otto – died in infancy.[10] When Hitler was three, the family moved to Passau, Germany.[11] There he acquired the distinctive lower Bavarian dialect, rather than Austrian German, which marked his speech all of his life.[12][13][14] In 1894 the family relocated to Leonding (near Linz), and in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld, near Lambach, where he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. Adolf attended school in nearby Fischlham. Hitler became fixated on warfare after finding a picture book about the Franco-Prussian War among his father's belongings.[15][16]

The move to Hafeld coincided with the onset of intense father-son conflicts caused by Adolf's refusal to conform to the strict discipline of his school.[17] Alois Hitler's farming efforts at Hafeld ended in failure, and in 1897 the family moved to Lambach. The eight-year-old Hitler took singing lessons, sang in the church choir, and even entertained thoughts of becoming a priest.[18] In 1898 the family returned permanently to Leonding. The death of his younger brother, Edmund, from measles on 2 February 1900 deeply affected Hitler. He changed from being confident and outgoing and an excellent student, to a morose, detached, and sullen boy who constantly fought with his father and teachers.[19]

Alois had made a successful career in the customs bureau and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps.[20] Hitler later dramatised an episode from this period when his father took him to visit a customs office, depicting it as an event that gave rise to an unforgiving antagonism between father and son, who were both strong-willed.[21][22][23] Ignoring his son's desire to attend a classical high school and become an artist, in September 1900 Alois sent Adolf to the Realschule in Linz.[24] (This was the same high school that Adolf Eichmann would attend some 17 years later.)[25] Hitler rebelled against this decision, and in Mein Kampf revealed that he did poorly in school, hoping that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to my dream."[26]

Hitler became obsessed with German nationalism from a young age.[27] He expressed loyalty only to Germany, despising the declining Habsburg Monarchy and its rule over an ethnically-variegated empire.[28][29] Hitler and his friends used the German greeting "Heil", and sang the German anthem "Deutschland Über Alles" instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.[30]

After Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's performance at school deteriorated. His mother allowed him to quit in autumn 1905.[31] He enrolled at the Realschule in Steyr in September 1904; his behaviour and performance showed some slight and gradual improvement.[32] In the autumn of 1905, after passing a repeat and the final exam, Hitler left the school without showing any ambitions for further schooling or clear plans for a career.[33]

Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich

From 1905, Hitler lived a bohemian life in Vienna, financed by orphan's benefits and support from his mother. He worked as a casual labourer and eventually as a painter, selling watercolours. The Academy of Fine Arts Vienna rejected him twice, in 1907 and 1908, because of his "unfitness for painting". The director recommended that Hitler study architecture,[34] but he lacked the academic credentials.[35] On 21 December 1907, his mother died aged 47. After the Academy's second rejection, Hitler ran out of money. In 1909 he lived in a homeless shelter, and by 1910, he had settled into a house for poor working men on Meldemannstraße.[36] At the time Hitler lived there, Vienna was a hotbed of religious prejudice and 19th-century racism.[37] Fears of being overrun by immigrants from the East were widespread, and the populist mayor, Karl Lueger, exploited the rhetoric of virulent antisemitism for political effect. Georg Schönerer's pan-Germanic antisemitism had a strong following and base in the Mariahilf district, where Hitler lived.[38] Hitler read local newspapers, such as the Deutsches Volksblatt, that fanned prejudice and played on Christian fears of being swamped by an influx of eastern Jews.[39] Hostile to what he saw as Catholic "Germanophobia", he developed an admiration for Martin Luther.[40]

The origin and first expression of Hitler's antisemitism have been difficult to locate.[41] Hitler states in Mein Kampf that he first became an antisemite in Vienna.[42] His close friend, August Kubizek, claimed that Hitler was a "confirmed antisemite" before he left Linz.[43] Kubizek's account has been challenged by historian Brigitte Hamann, who writes that Kubizek is the only person to have said that the young Hitler was an antisemite.[44] Hamann also notes that no antisemitic remark has been documented from Hitler during this period.[45] Historian Ian Kershaw suggests that if Hitler had made such remarks, they may have gone unnoticed because of the prevailing antisemitism in Vienna at that time.[46] Several sources provide strong evidence that Hitler had Jewish friends in his hostel and in other places in Vienna.[47][48] Historian Richard J. Evans states that "historians now generally agree that his notorious, murderous anti-Semitism emerged well after Germany’s defeat [in World War I], as a product of the paranoid 'stab-in-the-back' explanation for the catastrophe".[49]

Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to Munich.[50] Historians believe he left Vienna to evade conscription into the Austrian army.[51] Hitler later claimed that he did not wish to serve the Habsburg Empire because of the mixture of "races" in its army.[50] After he was deemed unfit for service—he failed his physical exam in Salzburg on 5 February 1914—he returned to Munich.[52]

World War I

At the outbreak of World War I, Hitler was a resident of Munich and volunteered to serve in the Bavarian Army as an Austrian citizen.[53] Posted to the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (1st Company of the List Regiment),[54][53] he served as a dispatch runner on the Western Front in France and Belgium,[55] spending nearly half his time well behind the front lines.[56][57] He was present at the First Battle of Ypres, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, and the Battle of Passchendaele, and was wounded at the Somme.[58]

He was decorated for bravery, receiving the Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1914.[58] Recommended by Hugo Gutmann, he received the Iron Cross, First Class, on 4 August 1918,[59] a decoration rarely awarded to one of Hitler's rank (Gefreiter). Hitler's post at regimental headquarters, providing frequent interactions with senior officers, may have helped him receive this decoration.[60] Though his rewarded actions may have been courageous, they were probably not highly exceptional.[61] He also received the Black Wound Badge on 18 May 1918.[62]

During his service at the headquarters, Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons, and instructions for an army newspaper. During the Battle of the Somme in October 1916, he was wounded either in the groin area[63] or the left thigh by a shell that had exploded in the dispatch runners' dugout.[64] Hitler spent almost two months in the Red Cross hospital at Beelitz, returning to his regiment on 5 March 1917.[65] On 15 October 1918, he was temporarily blinded by a mustard gas attack and was hospitalised in Pasewalk.[66] While there, Hitler learnt of Germany's defeat,[67] and—by his own account—on receiving this news, he suffered a second bout of blindness.[68]

Hitler became embittered over the collapse of the war effort, and his ideological development began to firmly take shape.[69] He described the war as "the greatest of all experiences", and was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery.[70] The experience reinforced his passionate German patriotism and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918.[71] Like other German nationalists, he believed in the Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back legend), which claimed that the German army, "undefeated in the field", had been "stabbed in the back" on the home front by civilian leaders and Marxists, later dubbed the "November criminals".[72]

The Treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany must relinquish several of its territories and demilitarise the Rhineland. The treaty imposed economic sanctions and levied heavy reparations on the country. Many Germans perceived the treaty—especially Article 231, which declared Germany responsible for the war—as a humiliation.[73] The Versailles Treaty and the economic, social, and political conditions in Germany after the war were later exploited by Hitler for political gains.[74]

Entry into politics

After World War I Hitler returned to Munich.[75] Having no formal education and career plans or prospects, he tried to remain in the army for as long as possible.[76] In July 1919 he was appointed Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance commando) of the Reichswehr, to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the German Workers' Party (DAP). While monitoring the activities of the DAP, Hitler became attracted to the founder Anton Drexler's antisemitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist, and anti-Marxist ideas.[77] Drexler favoured a strong active government, a "non-Jewish" version of socialism, and solidarity among all members of society. Impressed with Hitler's oratory skills, Drexler invited him to join the DAP. Hitler accepted on 12 September 1919,[78] becoming the party's 55th member.[79]

At the DAP, Hitler met Dietrich Eckart, one of its early founders and a member of the occult Thule Society.[80] Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him and introducing him to a wide range of people in Munich society.[81] To increase its appeal, the DAP changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party – NSDAP).[82] Hitler designed the party's banner of a swastika in a white circle on a red background.[83]

Hitler was discharged from the army in March 1920 and began working full time for the NSDAP. In February 1921—already highly effective at speaking to large audiences—he spoke to a crowd of over 6,000 in Munich.[84] To publicise the meeting, two truckloads of party supporters drove around town waving swastika flags and throwing leaflets. Hitler soon gained notoriety for his rowdy, polemic speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians, and especially against Marxists and Jews.[85] At the time, the NSDAP was centred in Munich, a major hotbed of anti-government German nationalists determined to crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar Republic.[86]

In June 1921, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to Berlin, a mutiny broke out within the NSDAP in Munich. Members of the its executive committee, some of whom considered Hitler to be too overbearing, wanted to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP).[87] Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July 1921 and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that his resignation would mean the end of the party.[88] Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich.[89] The committee agreed; he rejoined the party as member 3,680. He still faced some opposition within the NSDAP: Hermann Esser and his allies printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party.[89][a] In the following days, Hitler spoke to several packed houses and defended himself, to thunderous applause. His strategy proved successful: at a general membership meeting, he was granted absolute powers as party chairman, with only one nay vote cast.[90]

Hitler's vitriolic beer hall speeches began attracting regular audiences. He became adept at using populist themes targeted at his audience, including the use of scapegoats who could be blamed for the economic hardships of his listeners.[91][92][93] Historians have noted the hypnotic effect of his rhetoric on large audiences, and of his eyes in small groups. Kessel writes, "Overwhelmingly ... Germans speak with mystification of Hitler's 'hypnotic' appeal. The word shows up again and again; Hitler is said to have mesmerized the nation, captured them in a trance from which they could not break loose."[94] Historian Hugh Trevor-Roper described "the fascination of those eyes, which had bewitched so many seemingly sober men."[95] He used his personal magnetism and an understanding of crowd psychology to his advantage while engaged in public speaking.[96][97] Alfons Heck, a former member of the Hitler Youth, describes the reaction to a speech by Hitler: "We erupted into a frenzy of nationalistic pride that bordered on hysteria. For minutes on end, we shouted at the top of our lungs, with tears streaming down our faces: Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil! From that moment on, I belonged to Adolf Hitler body and soul".[98] Although his oratory skills and personal traits were generally received well by large crowds and at official events, some who had met Hitler privately noted that his appearance and demeanour failed to make a lasting impression on them.[99][100]

Early followers included Rudolf Hess, former air force pilot Hermann Göring, and army captain Ernst Röhm. Röhm became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organisation, the Sturmabteilung (SA, "Stormtroopers"), which protected meetings and frequently attacked political opponents. A critical influence on his thinking during this period was the Aufbau Vereinigung,[101] a conspiratorial group formed of White Russian exiles and early National Socialists. The group, financed with funds channelled from wealthy industrialists like Henry Ford, introduced him to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy, linking international finance with Bolshevism.[102]

Beer Hall Putsch

Hitler enlisted the help of World War I General Erich Ludendorff for an attempted coup known as the "Beer Hall Putsch" (also known as the "Hitler Putsch" or "Munich Putsch"). The Nazi Party had used Italian Fascism as a model for their appearance and policies. Hitler wanted to emulate Benito Mussolini's "March on Rome" (1922) by staging his own coup in Bavaria, to be followed by challenging the government in Berlin. Hitler and Ludendorff sought the support of Staatskommissar (state commissioner) Gustav von Kahr, Bavaria's de facto ruler. However, Kahr, along with Police Chief Hans Ritter von Seisser (Seißer) and Reichswehr General Otto von Lossow, wanted to install a nationalist dictatorship without Hitler.[103]

Hitler wanted to seize a critical moment for successful popular agitation and support.[104] On 8 November 1923 he and the SA stormed a public meeting of 3,000 people that had been organised by Kahr in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich. Hitler interrupted Kahr's speech and announced that the national revolution had begun, declaring the formation of a new government with Ludendorff.[105] Retiring to a backroom, Hitler, with handgun drawn, demanded and got the support of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow.[105] Hitler's forces initially succeeded in occupying the local Reichswehr and police headquarters; however, Kahr and his consorts quickly withdrew their support and neither the army nor the state police joined forces with him.[106] The next day, Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the Bavarian War Ministry to overthrow the Bavarian government, but police dispersed them.[107] Sixteen NSDAP members and four police officers were killed in the failed coup.[108]

Hitler fled to the home of Ernst Hanfstaengl, and by some accounts contemplated suicide.[109] He was depressed but calm when arrested on 11 November 1923 for high treason.[110] His trial began in February 1924 before the special People's Court in Munich,[111] and Alfred Rosenberg became temporary leader of the NSDAP. On 1 April Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg Prison.[112] He received friendly treatment from the guards; he was allowed mail from supporters and regular visits by party comrades. The Bavarian Supreme Court issued a pardon and he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections.[113] Including time on remand, Hitler had served just over one year in prison.[114]

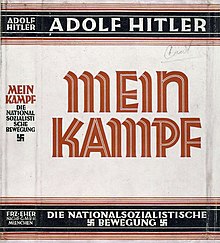

While at Landsberg, Hitler dictated most of the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle; originally entitled Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice) to his deputy, Rudolf Hess.[114] The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant, which Hitler called "my Bible".[115] The book laid out Hitler's plans for transforming German society into one based on race. Some passages implied genocide.[116] Published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, it sold 228,000 copies between 1925 and 1932. One million copies were sold in 1933, Hitler's first year in office. [117]

Rebuilding the NSDAP

At the time of Hitler's release from prison, politics in Germany had become less combative, and the economy had improved. This limited Hitler's opportunities for political agitation. As a result of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, the NSDAP and its affiliated organisations were banned in Bavaria. In a meeting with Prime Minister of Bavaria Heinrich Held on 4 January 1925, Hitler agreed to respect the authority of the state: he would only seek political power through the democratic process. The meeting paved the way for the ban on the NSDAP to be lifted.[118] However, Hitler was barred from public speaking, [119] a ban that remained in place until 1927.[120] To advance his political ambitions in spite of the ban, Hitler appointed Gregor Strasser, Otto Strasser, and Joseph Goebbels to organise and grow the NSDAP in northern Germany. A superb organiser, Gregor Strasser steered a more independent political course, emphasising the socialist element of the party's programme.[121]

Hitler ruled the NSDAP autocratically by asserting the Führerprinzip ("Leader principle"). Rank in the party was not determined by elections—positions were filled through appointment by those of higher rank, who demanded unquestioning obedience to the will of the leader.[122]

The stock market in the United States crashed on 24 October 1929. The impact in Germany was dire: millions were thrown out of work and several major banks collapsed. Hitler and the NSDAP prepared to take advantage of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to repudiate the Versailles Treaty, strengthen the economy, and provide jobs.[123]

Rise to power

| Election | Total votes | % votes | Reichstag seats | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:DtshMay 1924 | 1,918,300 | 6.5 | 32 | Hitler in prison |

| Template:DtshDecember 1924 | 907,300 | 3.0 | 14 | Hitler released from prison |

| Template:Dtsh1928 | 810,100 | 2.6 | 12 | |

| Template:Dtsh1930 | 6,409,600 | 18.3 | 107 | After the financial crisis |

| Template:Dtsh1932 | 13,745,000 | 37.3 | 230 | After Hitler was candidate for presidency |

| Template:Dtsh1932 | 11,737,000 | 33.1 | 196 | |

| Template:Dtsh1933 | 17,277,180 | 43.9 | 288 | During Hitler's term as chancellor of Germany |

Brüning administration

The Great Depression in Germany provided a political opportunity for Hitler. Germans were ambivalent to the parliamentary republic, which faced strong challenges from right- and left-wing extremists. The moderate political parties were increasingly unable to stem the tide of extremism, and the German referendum of 1929 had helped to elevate Nazi ideology.[125] The elections of September 1930 resulted in the break-up of a grand coalition and its replacement with a minority cabinet. Its leader, chancellor Heinrich Brüning of the Centre Party, governed through emergency decrees from the president, Paul von Hindenburg. Governance by decree would become the new norm and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government.[126] The NSDAP rose from obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote and 107 parliamentary seats in the 1930 election, becoming the second-largest party in parliament.[127]

Hitler made a prominent appearance at the trial of two Reichswehr officers, Lieutenants Richard Scheringer and Hans Ludin, in the autumn of 1930. Both were charged with membership in the NSDAP, at that time illegal for Reichswehr personnel.[128] The prosecution argued that the NSDAP was an extremist party, prompting defence lawyer Hans Frank to call on Hitler to testify in court.[129] On 25 September 1930 Hitler testified that his party would pursue political power solely through democratic elections,[130] a testimony that won him many supporters in the officer corps.[131]

Brüning's austerity measures brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular.[132] Hitler exploited this by targeting his political messages specifically at people who had been affected by the inflation of the 1920s and the Depression, such as farmers, war veterans, and the middle class.[133]

Hitler had formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925, but at the time did not acquire German citizenship. For almost seven years Hitler was stateless, unable to run for public office, and faced the risk of deportation.[134] On 25 February 1932 the interior minister of Brunswick, who was a member of the NSDAP, appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the Reichsrat in Berlin, making Hitler a citizen of Brunswick,[135] and thus of Germany.[136]

In 1932 Hitler ran against von Hindenburg in the presidential elections. The viability of his candidacy was underscored by a 27 January 1932 speech to the Industry Club in Düsseldorf, which won him support from many of Germany's most powerful industrialists.[137] However, Hindenburg had support from various nationalist, monarchist, Catholic, and republican parties, and some social democrats. Hitler used the campaign slogan "Hitler über Deutschland" ("Hitler over Germany"), a reference to both his political ambitions and to his campaigning by aircraft.[138] Hitler came in second in both rounds of the election, garnering more than 35% of the vote in the final election. Although he lost to Hindenburg, this election established Hitler as a strong force in German politics.[139]

Appointment as chancellor

The absence of an effective government prompted two influential politicians, Franz von Papen and Alfred Hugenberg, along with several other industrialists and businessmen, to write a letter to von Hindenburg. The signers urged Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as leader of a government "independent from parliamentary parties", which could turn into a movement that would "enrapture millions of people".[140][141]

Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler as chancellor after two further parliamentary elections—in July and November 1932—had not resulted in the formation of a majority government. Hitler was to head a short-lived coalition government formed by the NSDAP and Hugenberg's party, the German National People's Party (DNVP). On 30 January 1933 the new cabinet was sworn in during a brief and simple ceremony in Hindenburg's office. The NSDAP held three of the eleven posts: Hitler was named chancellor, Hermann Göring was named minister without portfolio, and Wilhelm Frick was appointed minister of the interior.[142]

Reichstag fire and March elections

As chancellor, Hitler worked against attempts by the NSDAP's opponents to build a majority government. Because of the political stalemate, he asked President Hindenburg to again dissolve the Reichstag, and elections were scheduled for early March. On 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set on fire. Göring blamed a communist plot, because Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe was found in incriminating circumstances inside the burning building.[143] At Hitler's urging, Hindenburg responded with the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February, which suspended basic rights and allowed detention without trial. Activities of the German Communist Party were suppressed, and some 4,000 communist party members were arrested.[144] Researchers, including William L. Shirer and Alan Bullock, are of the opinion that the NSDAP itself was responsible for starting the fire.[145][146]

In addition to political campaigning, the NSDAP engaged in paramilitary violence and the spread of anti-communist propaganda in the days preceding the election. On election day, 6 March 1933, the NSDAP's share of the vote increased to 43.9%, and the party acquired the largest number of seats in parliament. However, Hitler's party failed to secure an absolute majority, necessitating another coalition with the DNVP.[147]

Day of Potsdam and the Enabling Act

On 21 March 1933 the new Reichstag was constituted with an opening ceremony at the Garrison Church in Potsdam. This "Day of Potsdam" was held to demonstrate unity between the Nazi movement and the old Prussian elite and military. Hitler appeared in a morning coat and humbly greeted President von Hindenburg.[148][149]

To achieve full political control despite not having an absolute majority in parliament, Hitler's government brought the Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act) to a vote in the newly elected Reichstag. The act gave Hitler's cabinet full legislative powers for a period of four years and (with certain exceptions) allowed deviations from the constitution.[150] The bill required a two-thirds majority to pass. Leaving nothing to chance, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to keep several Social Democratic deputies from attending; the Communists had already been banned.[151]

On 23 March, the Reichstag assembled at the Kroll Opera House under turbulent circumstances. Ranks of SA men served as guards inside the building, while large groups outside opposing the proposed legislation shouted slogans and threats toward the arriving members of parliament.[152] The position of the Centre Party, the third largest party in the Reichstag, turned out to be decisive. After Hitler verbally promised party leader Ludwig Kaas that President von Hindenburg would retain his power of veto, Kaas announced the Centre Party would support the Enabling Act. Ultimately, the Enabling Act passed by a vote of 441–84, with all parties except the Social Democrats voting in favour. The Enabling Act, along with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a de facto legal dictatorship.[153]

Removal of remaining limits

At the risk of appearing to talk nonsense I tell you that the National Socialist movement will go on for 1,000 years! ... Don't forget how people laughed at me 15 years ago when I declared that one day I would govern Germany. They laugh now, just as foolishly, when I declare that I shall remain in power!

— Adolf Hitler to a British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934[154]

Having achieved full control over the legislative and executive branches of government, Hitler and his political allies embarked on a systematic suppression of the remaining political opposition. The Social Democratic Party was banned and all its assets seized.[155] While many trade union delegates were in Berlin for May Day activities, SA stormtroopers demolished trade union offices around the country. On 2 May 1933 all trade unions were forced to dissolve and their leaders were arrested; some were sent to concentration camps.[156] The German Labour Front was formed to represent all workers, administrators, and company owners together as one group. This new labour organisation reflected the concept of national socialism in the spirit of Hitler's "Volksgemeinschaft" (German racial community).[157]

By the end of June, the other parties had been intimidated into disbanding. With the help of the SA, Hitler pressured his nominal coalition partner, Hugenberg, into resigning. On 14 July 1933, the NSDAP was declared the only legal political party in Germany, thus formalising the situation after the passage of the Enabling Act.[157][155] The demands of the SA for more political and military power caused much anxiety among military, industrial, and political leaders. Hitler responded by purging the entire SA leadership in the Night of the Long Knives, which took place from 30 June to 2 July 1934.[158] Hitler targeted Ernst Röhm and other political adversaries (such as Gregor Strasser and former chancellor Kurt von Schleicher). Röhm and other SA leaders, along with a number of Hitler's political enemies, were rounded up, arrested, and shot.[159] While the international community and some Germans were shocked by the murders, many in Germany saw Hitler as restoring order.[160]

On 2 August 1934 President von Hindenburg died. The previous day, the cabinet had enacted the "Law Concerning the Highest State Office of the Reich".[161] This law stated that upon Hindenburg's death, the office of president would be abolished and its powers merged with those of the chancellor. Hitler thus became head of state as well as head of government, and was formally named as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor).[162] This law violated the Enabling Act, because although it allowed Hitler to deviate from the constitution, the Act explicitly barred him from passing any law tampering with the presidency. In 1932, the constitution had been amended to make the president of the High Court of Justice, not the chancellor, acting president pending new elections.[163] With this law, Hitler removed the last legal remedy by which he could be removed from office.

Hitler used the constitution of the former Weimar Republic to give his dictatorship the veneer of legality. Many of Hitler's decrees were based on the Reichstag Fire Decree (Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution). Thus, the presidential powers Hitler now held allowed him to couch his most repressive policies as emergency measures for the protection of public safety and order, thus allowing him to rule under what amounted to martial law. The Reichstag renewed the Enabling Act twice, though this was a mere formality since all other parties had been banned.[164]

As head of state, Hitler became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. The traditional loyalty oath of servicemen was altered to affirm loyalty to Hitler personally, rather than to the office of supreme commander.[165] On 19 August, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by a plebiscite with support of 90% of the electorate.[166]

In early 1938 Hitler forced his War Minister, Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, to resign when a police dossier was discovered showing that Blomberg's new wife had a record for prostitution.[167][168] Hitler removed army commander Colonel-General Werner von Fritsch after the Schutzstaffel (SS) produced allegations that he had taken part in a homosexual relationship.[169] Both men had already fallen into disfavour when they objected to his demand that they have the Wehrmacht ready to go to war as early as 1938.[170] Hitler used this incident, known as the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair, to consolidate his hold over the military. He assumed Blomberg's title of Commander-in-Chief, thus taking personal command of the armed forces. He replaced the Ministry of War with the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW), headed by General Wilhelm Keitel. On the same day, sixteen generals were stripped of their commands and 44 more were transferred; all were suspected of not being sufficiently pro-Nazi.[171] By early February 1938, twelve other generals had been removed.[172]

Having consolidated his political powers, Hitler suppressed or eliminated his opposition by a process termed Gleichschaltung ("bringing into line"). He attempted to gain additional public support by vowing to reverse the effects of the Depression and the Versailles Treaty.

Third Reich

Economy and culture

In August 1934 Hitler appointed Reichsbank president Hjalmar Schacht as his Minister of Economics. The following year Hitler appointed Schacht as Plenipotentiary for War Economy, in charge of preparing the economy for war.[173] Reconstruction and rearmament were financed through Mefo bills, printing money, and seizing the assets of people arrested as enemies of the State, including Jews.[174] Unemployment fell substantially, from six million in 1932 to one million in 1936.[175] Hitler oversaw one of the largest infrastructure improvement campaigns in German history, leading to the construction of dams, autobahns, railroads, and other civil works. Wages were slightly reduced in the pre–World War II years over those of the Weimar Republic, while the cost of living increased by 25%.[176] The average working week hours saw a steady increase during to shift to a war economy; by 1939, the average German worked between 47 to 50 hours per week.[177]

Hitler's government sponsored architecture on an immense scale. Albert Speer, instrumental in implementing Hitler's classicist reinterpretation of German culture, was placed in charge of the proposed architectural renovations of Berlin.[178] In 1936 Hitler opened the summer Olympic games in Berlin.

Rearmament and new alliances

In a meeting with German military leaders on 3 February 1933, Hitler spoke of "conquest for Lebensraum in the East and its ruthless Germanisation" as his ultimate foreign policy objectives.[179] In March, Prince Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow, secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office), issued a major statement of German foreign policy aims: Anschluss with Austria, the restoration of Germany's national borders of 1914, rejection of military restrictions under the Treaty of Versailles, the return of the former German colonies in Africa, and a German zone of influence in Eastern Europe. Hitler found Bülow's goals to be too modest.[180] In his speeches of this period, he stressed the peaceful goals of his policies and willingness to work within international agreements.[181] At the first meeting of his Cabinet in 1933, Hitler prioritised military spending over unemployment relief.[182]

Germany withdrew from the League of Nations and the World Disarmament Conference in October 1933.[183] In March 1935 Hitler announced an expansion of the Wehrmacht to 600,000 members—six times the number permitted by the Versailles Treaty—including development of an Air Force (Luftwaffe) and increasing the size of the Navy (Kriegsmarine). Britain, France, Italy, and the League of Nations condemned these plans as violations of the Treaty.[184] The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 allowed German tonnage to increase to 35% of that of the British navy. Hitler called the signing of the AGNA "the happiest day of his life", as he believed the agreement marked the beginning of the Anglo-German alliance he had predicted in Mein Kampf.[185] France and Italy were not consulted before the signing, directly undermining the League of Nations and putting the Treaty of Versailles on the path towards irrelevance.[186]

Germany reoccupied the demilitarised zone in the Rhineland in March 1936, in violation the Versailles Treaty. Hitler sent troops to Spain to support General Franco after receiving an appeal for help in July 1936. At the same time, Hitler continued his efforts to create an Anglo-German alliance.[187] In response to a growing economic crisis caused by his rearmament efforts, Hitler issued a memorandum ordering Göring to carry out a Four Year Plan to prepare Germany for war within the next four years.[188] The "Four-Year Plan Memorandum" of August 1936 envisaged an all-out struggle between "Judeo-Bolshevism" and German national socialism, which in Hitler's view required a committed effort of rearmament regardless of the economic costs.[189]

Count Galeazzo Ciano, foreign minister of Benito Mussolini's government, declared an axis between Germany and Italy, and on 25 November, Germany signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan. Britain, China, Italy, and Poland were also invited to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, but only Italy signed in 1937. Hitler abandoned his dream of an Anglo-German alliance, blaming "inadequate" British leadership.[190] At a secret meeting in the Reich Chancellery with his foreign ministers and military chiefs that November, Hitler stated his intention of acquiring Lebensraum ("living space") for the German people. He ordered preparations for war in the east, to begin as early as 1938 and no later than 1943. He stated that the conference minutes, recorded as the Hossbach Memorandum, were to be regarded as his "political testament" in the event of his death.[191] He felt the German economic crisis had reached a point that a severe decline in living standards in Germany could only be stopped by a policy of military aggression—seizing Austria and Czechoslovakia.[192][193] Hitler urged quick action, before Britain and France obtained a permanent lead in the arms race.[192] In early 1938, in the wake of the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair, Hitler asserted control of the military-foreign policy apparatus, dismissing Neurath as Foreign Minister and appointing himself Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht (supreme commander of the armed forces).[188] From early 1938 onwards, Hitler was carrying out a foreign policy ultimately aimed at war.[194]

Leadership style

Hitler promoted and followed the idea of the Führerprinzip. The principle relied on absolute obedience of all subordinates to their superiors; thus he viewed the government structure as a pyramid, with himself—the infallible leader—at the apex.[195] Hitler's leadership style was to give contradictory orders to his subordinates and to place them into positions where their duties and responsibilities overlapped with those of others, in order to have "the stronger one [do] the job".[196] In this way, Hitler fostered distrust, competition, and infighting among his subordinates in order to consolidate and maximise his own power. His cabinet never met after 1938, and he discouraged his ministers from meeting independently.[197][198] Hitler typically did not give written orders; instead he communicated them verbally, or had them conveyed through his close associate, Martin Bormann.[199] He entrusted Bormann with his paperwork, appointments, and personal finances; Bormann used his position to control the flow of information and access to Hitler.[200]

The Holocaust

If the international Jewish financiers outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the bolshevisation of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe![201]

— Adolf Hitler addressing the German Reichstag, 30 January 1939

A main Nazi concept was the notion of racial hygiene. On 15 September 1935, Hitler presented two laws—known as the Nuremberg Laws—to the Reichstag. The laws banned marriage between non-Jewish and Jewish Germans, and forbade the employment of non-Jewish women under the age of 45 in Jewish households. The laws deprived so-called "non-Aryans" of the benefits of German citizenship.[202] Hitler's early eugenic policies targeted children with physical and developmental disabilities in a programme dubbed Action Brandt, and later authorized a euthanasia programme for adults with serious mental and physical handicaps, now referred to as Action T4.[203]

Hitler's idea of Lebensraum, espoused briefly in Mein Kampf, focused on acquiring new territory for German settlement in Eastern Europe.[204] The Generalplan Ost ("General Plan for the East") called for the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to be deported to West Siberia, used as slave labour, or murdered;[205] the conquered territories were to be colonised by German or "Germanised" settlers.[206] The original plan called for this process to begin after the conquest of the Soviet Union, but when that failed to happen, Hitler moved the plans forward.[205][207] By January 1942 the decision had been taken to kill the Jews, Slavs, and other deportees considered undesirable.[208]

The Holocaust (the "Endlösung der jüdischen Frage" or "Final Solution of the Jewish Question") was organised and executed by Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich. The records of the Wannsee Conference—held on 20 January 1942 and led by Heydrich, with fifteen senior Nazi officials participating—provide the clearest evidence of systematic planning for the Holocaust. On 22 February Hitler was recorded saying to his associates, "we shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jews".[209] Approximately thirty Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps were used for this purpose.[210] By summer 1942 Auschwitz concentration camp was rapidly expanded to accept large numbers of deportees for killing or enslavement.[211]

Although no specific order from Hitler authorising the mass killings has surfaced,[212] he approved the Einsatzgruppen—killing squads that followed the German army through Poland, the Baltic, and the Soviet Union[213]—and he was well informed about their activities.[214] During interrogations by Soviet intelligence officers, the records of which were declassified over fifty years later, Hitler's valet, Heinz Linge, and his adjutant, Otto Günsche, stated that Hitler had a direct interest in the development of gas chambers.[215]

Between 1939 and 1945, the SS, assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, were responsible for the deaths of eleven to fourteen million people, including about six million Jews, representing two-thirds of the Jewish population in Europe,[216][217] and between 500,000 and 1,500,000 Romani people.[218] Deaths took place in concentration and extermination camps, ghettos, and through mass executions. Many victims of the Holocaust were gassed to death, whereas others died of starvation or disease while working as slave labourers.[219]

Hitler's policies also resulted in the killings of Poles[220] and Soviet prisoners of war, communists and other political opponents, homosexuals, the physically and mentally disabled,[221][222] Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists, and trade unionists. Hitler never appeared to have visited the concentration camps and did not speak publicly about the killings.[223]

World War II

Early diplomatic successes

Alliance with Japan

In February 1938, on the advice of his newly appointed Foreign Minister, the strongly pro-Japanese Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler ended the Sino-German alliance with the Republic of China to instead enter into an alliance with the more modern and powerful Japan. Hitler announced German recognition of Manchukuo, the Japanese-occupied state in Manchuria, and renounced German claims to their former colonies in the Pacific held by Japan.[224] Hitler ordered an end to arms shipments to China and recalled all German officers working with the Chinese Army.[224] In retaliation, Chinese General Chiang Kai-shek cancelled all Sino-German economic agreements, depriving the Germans of many Chinese raw materials.[225]

Austria and Czechoslovakia

On 12 March 1938 Hitler declared unification of Austria with Nazi Germany in the Anschluss.[226][227] Hitler then turned his attention to the ethnic German population of the Sudetenland district of Czechoslovakia.[228]

On 28–29 March 1938 Hitler held a series of secret meetings in Berlin with Konrad Henlein of the Sudeten Heimfront (Home Front), the largest of the ethnic German parties of the Sudetenland. The men agreed that Henlein would demand increased autonomy for Sudeten Germans from the Czechoslovakian government, thus providing a pretext for German military action against Czechoslovakia. In April 1938 Henlein told the foreign minister of Hungary that "whatever the Czech government might offer, he would always raise still higher demands ... he wanted to sabotage an understanding by all means because this was the only method to blow up Czechoslovakia quickly".[229] In private, Hitler considered the Sudeten issue unimportant; his real intention was a war of conquest against Czechoslovakia.[230]

In April 1938 Hitler ordered the OKW to prepare for Fall Grün ("Case Green"), the code name for an invasion of Czechoslovakia.[231] As a result of intense French and British diplomatic pressure, on 5 September 1938 Czechoslovakian President Edvard Beneš unveiled the "Fourth Plan" for constitutional reorganisation of his country, which agreed to most of Henlein's demands for Sudeten autonomy.[232] Henlein's Heimfront responded to Beneš' offer with a series of violent clashes with the Czechoslovakian police that led to the declaration of martial law in certain Sudeten districts.[233][234]

Germany was dependent on imported oil; a confrontation with Britain over the Czechoslovakian dispute could curtail Germany's oil supplies. Hitler called off Fall Grün, originally planned for 1 October 1938.[235] On 29 September 1938 Hitler, Neville Chamberlain, Édouard Daladier, and Benito Mussolini attended a one-day conference in Munich that led to the Munich Agreement, which handed over the Sudetenland districts to Germany.[236][237]

Chamberlain was satisfied with the Munich conference, calling the outcome "peace for our time", while Hitler was angered about the missed opportunity for war in 1938;[238][239] he expressed his disappointment in a speech on 9 October 1938 in Saarbrücken.[240] In Hitler's view, the British-brokered peace, although favourable to the ostensible German demands, was a diplomatic defeat which spurred his intent of limiting British power to pave the way for the eastern expansion of Germany.[241][242] As a result of the summit, Hitler was selected Time magazine's Man of the Year for 1938.[243]

In late 1938 and early 1939, the continuing economic crisis caused by rearmament forced Hitler to make major defence cuts.[244] In his "Export or die" speech of 30 January 1939, he called for an economic offensive to increase German foreign exchange holdings to pay for raw materials such as high-grade iron needed for military weapons.[244]

On 15 March 1939, in violation of the Munich accord and possibly as a result of the deepening economic crisis requiring additional assets,[245] Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht to invade Prague, and from Prague Castle proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate.[246]

Start of World War II

In private discussions in 1939, Hitler described Britain as the main enemy to be defeated. In his view, Poland's obliteration as a sovereign nation was a necessary prelude to that goal. The eastern flank would therefore be secured and land would be added to Germany's Lebensraum.[247] Offended by the British "guarantee" of Polish independence issued 31 March 1939, he told his associates, "I shall brew them a devil's drink".[248] In a speech in Wilhelmshaven for the launch of the battleship Tirpitz on 1 April 1939, he threatened to denounce the Anglo-German Naval Agreement if the British persisted with their guarantee of Polish independence, which he perceived as an "encirclement" policy.[248] He wanted Poland to become either a German satellite state or be otherwise neutralised to secure the Reich's eastern flank, and to prevent a possible British blockade.[249] He initially favoured the idea of a satellite state; when this was rejected by the Polish government, he decided to invade. He made this the main German foreign policy goal of 1939.[250] On 3 April 1939 Hitler ordered the military to prepare for Fall Weiss ("Case White"), the plan for an invasion of Poland on 25 August 1939.[250] In a speech before the Reichstag on 28 April, he renounced both the Anglo-German Naval Agreement and the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact. In August Hitler told his generals that his original plan for 1939 was to "... establish an acceptable relationship with Poland in order to fight against the West".[251] Historians such as William Carr, Gerhard Weinberg, and Ian Kershaw have argued that one reason for Hitler's rush to war was his morbid and obsessive fear of an early death, and hence his feeling that he did not have long to accomplish his work.[252][253][254]

Hitler was concerned that a military attack against Poland could result in a premature war with Britain.[249][255] However, Hitler's foreign minister—and former Ambassador to London—Joachim von Ribbentrop assured him that neither Britain nor France would honour their commitments to Poland, and that a German–Polish war would only be a limited regional war.[256][257] Ribbentrop claimed that in December 1938 the French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet, had stated that France considered Eastern Europe as Germany's exclusive sphere of influence;[258] Ribbentrop showed Hitler diplomatic cables that supported his analysis.[259] The German Ambassador in London, Herbert von Dirksen, supported Ribbentrop's analysis with a dispatch in August 1939, reporting that Chamberlain knew "the social structure of Britain, even the conception of the British Empire, would not survive the chaos of even a victorious war", and so would back down.[257] Accordingly, on 21 August 1939 Hitler ordered a military mobilisation against Poland.[260]

Hitler's plans for a military campaign in Poland in late August or early September required tacit Soviet support.[261] The non-aggression pact (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) between Germany and the Soviet Union, led by Joseph Stalin,[262] included secret protocols with an agreement to partition Poland between the two countries. In response to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—and contrary to the prediction of Ribbentrop that the newly-formed pact would sever Anglo-Polish ties—Britain and Poland signed the Anglo-Polish alliance on 25 August 1939. This, along with news from Italy that Mussolini would not honour the Pact of Steel, caused Hitler to postpone the attack on Poland from 25 August to 1 September.[263] In the days before the start of the war, Hitler tried to manoeuvre the British into neutrality by offering a non-aggression guarantee to the British Empire on 25 August and by having Ribbentrop present a last-minute peace plan with an impossibly short time limit in an effort to then blame the war on British and Polish inaction.[264][265]

As a pretext for a military aggression against Poland, Hitler claimed the Free City of Danzig and the right to extraterritorial roads across the Polish Corridor, which Germany had ceded under the Versailles Treaty.[266] Despite his concerns over a possible British intervention, Hitler was ultimately not deterred from his aim of invading Poland,[267] and on 1 September 1939 Germany invaded western Poland. In response, Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. This surprised Hitler, prompting him to turn to Ribbentrop and angrily ask "Now what?"[268] France and Britain did not act on their declarations immediately, and on 17 September, Soviet forces invaded eastern Poland.[269]

Poland never will rise again in the form of the Versailles treaty. That is guaranteed not only by Germany, but also ... Russia.

The fall of Poland was followed by what contemporary journalists dubbed the "Phoney War" or Sitzkrieg ("sitting war"). Hitler instructed the two newly-appointed Gauleiters of north-western Poland, Albert Forster of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia and Arthur Greiser of Reichsgau Wartheland, to "Germanise" their areas, and promised them "There would be no questions asked" about how this was accomplished.[271] To Himmler's chagrin, Forster had local Poles sign forms stating that they had German blood, and required no further documentation.[272] On the other hand, Greiser carried out a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign on the Polish population in his purview.[271] Greiser complained to Hitler that Forster was allowing thousands of Poles to be accepted as "racial" Germans and thus, in Greiser's view, endangering German "racial purity". Hitler told Himmler and Greiser to take up their difficulties with Forster, and not to involve him.[271] Hitler's handling of the Forster–Greiser dispute has been advanced as an example of Kershaw's theory of "working towards the Führer": Hitler issued vague instructions and expected his subordinates to work out policies on their own.

Another dispute broke out between different factions. One side, represented by Himmler and Greiser, championed carrying out ethnic cleansing in Poland, and another side, represented by Göring and Hans Frank, Governor-General of the General Government territory of occupied Poland, called for turning Poland into the "granary" of the Reich.[273] At a conference held at Göring's Karinhall estate on 12 February 1940, the dispute was initially settled in favour of the Göring–Frank view of economic exploitation, which ended the economically disruptive mass expulsions.[273] On 15 May 1940, however, Himmler presented Hitler with a memo entitled "Some Thoughts on the Treatment of Alien Population in the East", which called for expulsion of the entire Jewish population of Europe into Africa and reducing the remainder of the Polish population to a "leaderless class of labourers".[273] Hitler called Himmler's memo "good and correct";[273] and, ignoring Göring and Frank, implemented the Himmler–Greiser policy in Poland.

Hitler began a military build-up on Germany's western border, and in April 1940, German forces invaded Denmark and Norway. On 9 April Hitler proclaimed the birth of the "Greater Germanic Reich" to his associates; this was his vision of a united empire of the Germanic nations of Europe, where the Dutch, Flemish, Scandinavians, and other peoples would join into a single, racially-pure polity under German leadership.[274] In May 1940, Hitler's forces attacked France, and conquered Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium. These victories prompted Mussolini to have Italy join forces with Hitler on 10 June 1940. France surrendered on 22 June 1940.[275]

Britain, whose forces were forced to leave France by sea from Dunkirk,[276] continued to fight alongside other British dominions in the Battle of the Atlantic. Hitler made peace overtures to the British, now led by Winston Churchill, and when these were rejected he ordered bombing raids on the United Kingdom. Hitler's prelude to a planned invasion of the UK was a series of aerial attacks in the Battle of Britain on Royal Air Force airbases and radar stations in South-East England. However, the German Luftwaffe failed to defeat the Royal Air Force.[277]

On 27 September 1940 the Tripartite Pact was signed in Berlin by Saburō Kurusu of Imperial Japan, Hitler, and Italian foreign minister Ciano.[278] The agreement was later expanded to include Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. They were collectively known as the Axis powers. The purpose of the pact was to deter the United States from supporting the British. By the end of October 1940, air superiority for the invasion of Britain—Operation Sea Lion—could not be achieved, and Hitler ordered nightly air raids of British cities, including London, Plymouth, and Coventry.[279]

In the Spring of 1941, Hitler was distracted from his plans for the East by military activities in North Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East. In February, German forces arrived in Libya to bolster the Italian presence. In April, Hitler launched the invasion of Yugoslavia, quickly followed by the invasion of Greece.[280] In May, German forces were sent to support Iraqi rebel forces fighting against the British and to invade Crete. On 23 May, Hitler released Führer Directive No. 30.[281]

Path to defeat

On 22 June 1941, contravening the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact of 1939, three million German troops attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa.[282] The invasion seized a huge area, including the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. However, the German advance was stopped outside Moscow in December 1941 by the Russian Winter and fierce Soviet resistance.[283]

Soviet troop concentrations on Germany's eastern border in the spring of 1941 may have prompted Hitler to engage in a Flucht nach vorn ("flight forward") to get in front of an inevitable conflict.[284] Viktor Suvorov, Ernst Topitsch, Joachim Hoffmann, Ernst Nolte, and David Irving have argued that the official reason for Barbarossa given by the German military was the real reason—a preventive war to avert an impending Soviet attack scheduled for July 1941. This theory, however, has been faulted; American historian Gerhard Weinberg once compared the advocates of the preventive war theory to believers in "fairy tales".[285]

The Wehrmacht invasion of the Soviet Union reached its peak on 2 December 1941, when the 258th Infantry Division advanced to within 15 miles (24 km) of Moscow, close enough to see the spires of the Kremlin.[283] However, they were not prepared for the harsh conditions of the Russian winter, and Soviet forces drove back the German troops over 320 kilometres (200 mi).

On 7 December 1941 Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Four days later, Hitler's formal declaration of war against the United States engaged Germany in war against a coalition that included the world's largest empire (the British Empire), the world's greatest industrial and financial power (the United States), and the world's largest army (the Soviet Union).[286]

When Himmler met Hitler on 18 December 1941 and posed the question "What to do with the Jews of Russia?", Hitler replied "als Partisanen auszurotten" ("exterminate them as partisans").[287] Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer has commented that the remark is probably as close as historians will ever get to a definitive order from Hitler for the genocide carried out during the Holocaust.[287]

In late 1942 German forces were defeated in the second battle of El Alamein,[288] thwarting Hitler's plans to seize the Suez Canal and the Middle East. In February 1943 the Battle of Stalingrad ended with the destruction of the German Sixth Army. Thereafter came a decisive defeat at the Battle of Kursk.[289] Hitler's military judgment became increasingly erratic, and Germany's military and economic position deteriorated along with Hitler's health. Kershaw and others believe that Hitler may have suffered from Parkinson's disease.[290]

Following the allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, Mussolini was deposed by Pietro Badoglio,[291] who surrendered to the Allies. Throughout 1943 and 1944, the Soviet Union steadily forced Hitler's armies into retreat along the Eastern Front. On 6 June 1944 the Western Allied armies landed in northern France in what was one of the largest amphibious operations in history, Operation Overlord.[292] As a result of these significant setbacks for the German army, many of its officers concluded that defeat was inevitable and that Hitler's misjudgement or denial would drag out the war and result in the complete destruction of the country.[293] Several high-profile assassination attempts against Hitler occurred during this period.

Between 1939 and 1945 there were many plans to assassinate Hitler, some of which proceeded to significant degrees.[294] The most well-known came from within Germany and was at least partly driven by the increasing prospect of a German defeat in the war.[295] In July 1944, in the 20 July plot, part of Operation Valkyrie, Claus von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in one of Hitler's headquarters, the Wolf's Lair at Rastenburg. Hitler narrowly survived because someone had unknowingly pushed the briefcase that contained the bomb behind a leg of the heavy conference table. When the bomb exploded, the table deflected much of the blast away from Hitler. Later, Hitler ordered savage reprisals resulting in the execution of more than 4,900 people.[296]

Hitler made all the major military decisions personally. Historians who have assessed his performance agree that after a strong start, he became so inflexible after 1941 that he squandered the military strengths Germany possessed. Historian Antony Beevor argues that at the start of the war, "Hitler was a fairly inspired leader, because his genius lay in assessing the weaknesses of others and exploiting those weaknesses." However, from 1941 onward, "he became completely sclerotic. He would not allow any form of retreat or flexibility among his field commanders, and that of course was catastrophic."[297]

Defeat and death

By late 1944, the Red Army had driven the German army back into Western Europe, and the Western Allies were advancing into Germany. After being informed of the failure of his Ardennes Offensive, Hitler realised that Germany was going to lose the war. His hope, buoyed by the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt on 12 April 1945, was to negotiate peace with America and Britain.[298] Acting on his view that Germany's military failures had forfeited its right to survive as a nation, Hitler ordered the destruction of all German industrial infrastructure before it could fall into Allied hands.[299] Execution of this scorched earth plan was entrusted to arms minister Albert Speer, who quietly disobeyed the order.[299]

On 20 April, his 56th birthday, Hitler made his last trip from the Führerbunker ("Führer's shelter") to the surface. In the ruined garden of the Reich Chancellery, he awarded Iron Crosses to boy soldiers of the Hitler Youth.[300] By 21 April, Georgy Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front had broken through the last defences of German General Gotthard Heinrici's Army Group Vistula during the Battle of the Seelow Heights and advanced into the outskirts of Berlin.[301] In denial about the increasingly dire situation, Hitler placed his hopes on the units commanded by Waffen SS General Felix Steiner, the Armeeabteilung Steiner ("Army Detachment Steiner"). Hitler ordered Steiner to attack the northern flank of the salient and the German Ninth Army was ordered to attack northward in a pincer attack.[302]

During a military conference on 22 April, Hitler asked about Steiner's offensive. After a long silence, he was told that the attack had never been launched and that the Russians had broken through into Berlin. This news prompted Hitler to ask everyone except Wilhelm Keitel, Alfred Jodl, Hans Krebs, and Wilhelm Burgdorf to leave the room.[303] Hitler then launched a tirade against the treachery and incompetence of his commanders, culminating in his declaration—for the first time—that the war was lost. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself.[304]

Goebbels made a proclamation on 23 April urging the citizens of Berlin to courageously defend the city.[303] That same day, Göring sent a telegram from Berchtesgaden in Bavaria, arguing that since Hitler was cut off in Berlin, he, Göring, should assume leadership of Germany. Göring set a time limit, after which he would consider Hitler incapacitated.[305] Hitler responded angrily by having Göring arrested, and when writing his will on 29 April, he removed Göring from all his positions in the government.[306][307]

Berlin became completely cut off from the rest of Germany.[308] On 28 April, Hitler discovered that Himmler was trying to discuss surrender terms with the Western Allies.[309] He ordered Himmler's arrest and had Hermann Fegelein (Himmler's SS representative at Hitler's HQ in Berlin) shot.[310]

After midnight on 29 April, Hitler married Eva Braun in a small civil ceremony in a map room within the Führerbunker. After a modest wedding breakfast with his new wife, he then took secretary Traudl Junge to another room and dictated his last will and testament.[311][b] The event was witnessed and documents signed by Hans Krebs, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Joseph Goebbels, and Martin Bormann.[312] Later that afternoon, Hitler was informed of the assassination of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, which presumably increased his determination to avoid capture.[313]

On 30 April 1945, after intense street-to-street combat, when Soviet troops were within a block or two of the Reich Chancellery, Hitler and Braun committed suicide; Braun bit into a cyanide capsule[314] and Hitler shot himself with his 7.65 mm (0.3 in) Walther PPK pistol.[315] The lifeless bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun were carried up the stairs and through the bunker's emergency exit to the bombed-out garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were placed in a bomb crater[316] and doused with petrol. The corpses were set on fire[317] and the Red Army shelling continued.[318]

Berlin surrendered on 2 May. Records in the Soviet archives—obtained after the fall of the Soviet Union—showed that the remains of Hitler, Braun, Joseph and Magda Goebbels, the six Goebbels children, General Hans Krebs, and Hitler's dogs, were repeatedly buried and exhumed.[319] On 4 April 1970 a Soviet KGB team with detailed burial charts secretly exhumed five wooden boxes which had been buried at the SMERSH facility in Magdeburg. The remains from the boxes were thoroughly burned and crushed, after which the ashes were thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.[320]

Legacy

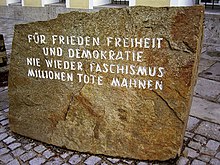

For peace, freedom

and democracy

never again fascism

millions of dead remind [us]"

Hitler's suicide was likened by contemporaries to a "spell" being broken.[321][322] According to historian John Toland, without its leader, National Socialism "burst like a bubble".[323]

Hitler's actions and Nazi ideology are almost universally regarded as gravely immoral.[324] His political programme had brought about a world war, leaving behind a devastated and impoverished Eastern and Central Europe. Germany itself suffered wholesale destruction, characterised as "Zero Hour".[325] Hitler's policies inflicted human suffering on an unprecedented scale;[326] the Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of an estimated 21 million civilians and prisoners of war.[327] In addition, 29 million soldiers were killed in the European theater of World War II.[327] Historians, philosophers, and politicians often apply the word "evil" in describing the Nazi regime.[328] In Germany and Austria, Holocaust denial and the display of Nazi symbols such as the swastika are prohibited by law.

Historian Friedrich Meinecke described Hitler as "one of the great examples of the singular and incalculable power of personality in historical life".[329] The English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper saw him as "among the 'terrible simplifiers' of history, the most systematic, the most historical, the most philosophical, and yet the coarsest, cruellest, least magnanimous conqueror the world has ever known."[330] For the historian John M. Roberts, Hitler's defeat marked the end of a phase of European history dominated by Germany.[331] In its place emerged the Cold War, a global confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States.[332]

Religious views

Hitler saw the church as important politically, as a conservative influence on society. He felt that if the church were eliminated the faithful would turn to mysticism, which he thought would be a step backwards politically and culturally. Though he never officially left the Catholic Church, he had no real attachment to it.[333] After leaving home he never attended Mass or received the sacraments.[334] He favoured aspects of Protestantism that suited his own views, and adopted some elements of the Catholic Church's hierarchical organisation, liturgy, and phraseology in his politics.[335][336]

In public, Hitler often praised Christian heritage and German Christian culture, and professed a belief in an "Aryan" Jesus Christ—a Jesus who fought against the Jews.[337] He spoke of his interpretation of Christianity as a central motivation for his antisemitism, stating that "As a Christian I have no duty to allow myself to be cheated, but I have the duty to be a fighter for truth and justice."[338][339] In private, he was more critical of traditional Christianity, considering it a religion fit only for slaves; he admired the power of Rome but maintained a severe hostility towards its teaching.[340] Historian John S. Conway states that Hitler held a "fundamental antagonism" towards the Christian churches.[341]

In political relations with the church, Hitler adopted a strategy "that suited his immediate political purposes".[341] According to a US Office of Strategic Services report, Hitler had a general plan, even before his rise to power, to destroy the influence of Christian churches within the Reich.[342][343] The report titled "The Nazi Master Plan" stated that the destruction of the church was a goal of the movement right from the start, but that it was inexpedient to express this extreme position publicly.[344] His intention, according to Bullock, was to wait until the war was over to destroy the influence of Christianity.[340]

Hitler admired the Muslim military tradition, but considered Arabs as "racially inferior".[345] He believed that the racially-superior Germans, in conjunction with Islam, could have conquered much of the world during the Middle Ages.[346] During a meeting with a Japanese professor in 1931, Hitler praised the Shinto religion and Japanese culture.[347] Although Himmler was interested in the occult, the interpretation of runes, and tracing the prehistoric roots of the Germanic people, Hitler was more pragmatic, and his ideology centred on more practical concerns.[348][349]

Health

Researchers have variously suggested that Hitler suffered from irritable bowel syndrome, skin lesions, irregular heartbeat, Parkinson's disease,[350][290] syphilis,[350] and tinnitus.[351] In a report prepared for the Office of Strategic Services in 1943, Walter C. Langer of Harvard University described Hitler as a "neurotic psychopath."[352] Theories about Hitler's medical condition are difficult to prove, and according them too much weight may have the effect of attributing many of the events and consequences of the Third Reich to the possibly impaired physical health of one individual.[353] Kershaw feels that it is better to take a broader view of German history by examining what social forces led to the Third Reich and its policies rather than to pursue narrow explanations for the Holocaust and World War II based on only one person.[354]

Hitler followed a vegetarian diet.[355] At social events he sometimes gave graphic accounts of the slaughter of animals in an effort to make his dinner guests shun meat.[356] A fear of cancer (from which his mother died)[357] is the most widely cited reason for Hitler's dietary habits. An antivivisectionist, Hitler may have followed his selective diet out of a profound concern for animals.[358] Bormann had a greenhouse constructed near the Berghof (near Berchtesgaden) to ensure a steady supply of fresh fruit and vegetables for Hitler throughout the war. Hitler despised alcohol[359] and was a non-smoker. He promoted aggressive anti-smoking campaigns throughout Germany.[360] Hitler began using amphetamine occasionally after 1937 and became addicted to the drug in the fall of 1942.[361] Albert Speer linked this use of amphetamines to Hitler's increasingly inflexible decision making (for example, never to allow military retreats).[362]

Prescribed ninety different medications during the war years, Hitler took many pills each day for chronic stomach problems and other ailments.[363] He suffered ruptured eardrums as a result of the 20 July plot bomb blast in 1944, and two hundred wood splinters had to be removed from his legs.[364] Newsreel footage of Hitler shows tremors of his hand and a shuffling walk, which began before the war and worsened towards the end of his life. Hitler's personal physician, Theodor Morell, treated Hitler with a drug that was commonly prescribed in 1945 for Parkinson's disease. Ernst-Günther Schenck and several other doctors who met Hitler in the last weeks of his life each formed a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease.[363][365]

Family

To the public, Hitler promoted his own image as that of a celibate man without a domestic life, dedicated entirely to his political mission and the nation.[134][366] He met his mistress, Eva Braun, in 1929,[367] and married her in April 1945.[368] In September 1931, his half-niece, Geli Raubal, committed suicide with Hitler's gun in his Munich apartment. It was rumoured among contemporaries that Geli was in a romantic relationship with him, and her death was a source of deep, lasting pain.[369] Paula Hitler, the last living member of the immediate family, died in 1960.[370]

Hitler in media

Hitler used documentary films as a propaganda tool. He was involved and appeared in a series of films by the pioneering filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl via Universum Film AG (UFA):[371]

- Der Sieg des Glaubens (Victory of Faith, 1933)

- Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, 1934), co-produced by Hitler

- Tag der Freiheit: Unsere Wehrmacht (Day of Freedom: Our Armed Forces, 1935)

- Olympia (1938)

See also

- Führermuseum

- Hitler: A Film from Germany

- Julius Schaub – chief aide

- Karl Mayr – Hitler's superior in army Intelligence 1919–1920

- Karl Wilhelm Krause – personal valet

- List of books by or about Adolf Hitler

- Mein Kampf (online versions)

- Poison Kitchen

- Streets named after Adolf Hitler

- Vorbunker