Clozapine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Clozaril, Leponex, Versacloz, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691001 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60 to 70% |

| Metabolism | Liver, by several CYP isozymes |

| Elimination half-life | 4 to 26 hours (mean value 14.2 hours in steady state conditions) |

| Excretion | 80% in metabolized state: 30% biliary and 50% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.831 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

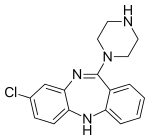

| Formula | C18H19ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 326.83 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 183 °C (361 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 0.1889[4] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clozapine, sold under the brand name Clozaril among others,[1] is the first atypical antipsychotic medication.[5] It is usually used in tablet or liquid form for people diagnosed with schizophrenia who have had an inadequate response to other antipsychotics or who have been unable to tolerate other drugs due to extrapyramidal side effects. It is also used for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's Disease.[6][7] It is regarded as the gold-standard treatment when other medication has been insufficiently effective and its use is recommended by multiple international treatment guidelines.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Compared to other antipsychotics there is an increased risk of blood dyscrasias, in particular agranulocytosis in the first 18 weeks of treatment, after one year this risk reduces to that found in most antipsychotics and so it's use is reserved for people who have not responded to two other antipsychotics and then only with stringent blood monitoring.[6] Although it was first used in the 1970's eight deaths from agranulocytosis were noted in Finland.[14] At the time it was not clear if this exceeded the established rate of this side effects which is also found in other antipsychotics and although the drug was not completely withdrawn its use became limited.[15] The role of clozapine in treatment resistant schizophrenia was established by the landmark Clozaril Collaborative Study Group Study #30 in which clozapine showed marked benefits compared to chlorpromazine in a group of patients with protracted psychosis and who had already shown an inadequate response to other antipsychotics.[16]Whilst there are significant side effects clozapine remains the most effective treatment when one or more other antipsychotics have had an inadequate response and clozapine use is associated with multiple improved outcomes including all cause mortality, suicide and reduced hospitalisation.[17][18]

Compared to other antipsychotics clozapine is associated with an increased risk of low white blood cells. Neutropenia occurs in approximately 3.8% of cases and agranulocytosis in 0.4%.[19] These are potentially serious side effects and agranulocytosis can result in death. To mitigate this risk clozapine is only used with mandatory blood monitoring. The exact schedules and blood count thresholds vary internationally[20] and the thresholds at which clozapine can be used in the U.S. has been lower than those currently used in the U.K. for some time.[21] The effectiveness of the risk management strategies used is such that deaths from these side effects are very rare occurring at approximately 1 in 7700 patients treated.[22] Almost all the adverse blood reactions occur within the first year of treatment and the majority within the first 18 weeks.[19] Other serious risks include seizures, inflammation of the heart, high blood sugar levels, constipation, and in older people with psychosis as a result of dementia, an increased risk of death.[23][24] Common adverse effects include drowsiness, increased saliva production, low blood pressure, blurred vision, weight gain, and dizziness.[25] Clozapine is not normally associated with tardive dyskinesia (TD) and is recommended as the drug of choice when this is present although some case reports describe clozapine-induced TD[26]. Its mechanism of action is not entirely clear.[25]

In a network comparative meta-analysis of 15 antipsychotic drugs clozapine was significantly more effective than all other drugs.[27]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[28] It is available as a generic medication.[25]

Clinical uses

Clozapine is usually used for people diagnosed with schizophrenia who have had an inadequate response to other antipsychotics or who have been unable to tolerate other drugs due to extrapyramidal side effects. It is also used for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's Disease.[6][7] It is regarded as the gold-standard treatment when other medication has been insufficiently effective and its use is recommended by multiple international treatment guidelines, supported by systematic reviews and meta-analysis.[8][9][10][11][12][13][29] [30] Whilst all current guidelines reserve clozapine to individuals when two other antipsychotics evidence indicates that clozapine might be used as a second line drug[31]. Clozapine treatment has been demonstrated to produced improved outcomes in multiple domains including; a reduced risk of hospitalisation, a reduced risk of drug discontinuation, a reduction in overall symptoms and has improved efficacy in the treatment of positive psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. [32][33][34] Despite a range of side effects patients report good levels of satisfaction and long term adherence is favourable compared to other antipsychotics.[35] Very long term follow-up studies reveal multiple benefits in terms of reduced mortality,[36][37] with a particularly strong effect for reduced death by suicide, clozapine is the only antipsychotic known to have an effect reducing the risk of attempted or completed suicide.[38] Clozapine has a significant anti-aggressive effect.[39][40][41][42][43] Clozapine is widely used in secure and forensic mental health settings where improvements in aggression, shortened admission and reductions in restrictive practice such as seclusion have been found[44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52]. In secure hospitals clozapine has also been used in the treatment of borderline and antisocial personality disorder when this has been associated with violence or self-harm. [53][54][55] Although oral treatment is almost universal clozapine has on occasion been enforced using either nasogastric or a short acting injection although in almost 50% of the reported cases patients agreed to take oral medication prior to the use of a coercive intervention.[56] [57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Clozapine is widely recognised as being underused with wide variation in prescribing [67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74], especially in patients with African heritage[75][76][77][78][79]. Part of the explanation for the underuse of clozapine in patients with African heritage is the presence of benign ethnic neutropenia. Benign reductions in neutrophils are observed in individuals of all ethnic backgrounds. Benign ethnic neutropenia (BEN), neutropenia without immune dysfunction or increased liability to infection is not due to abnormal neutrophil production; although, the exact aetiology of the reduction in circulating cells remains unknown. BEN is associated with several ethnic groups, but in particular those with Black African and West African ancestry.[80] A difficulty with the use of clozapine is that neutrophil counts have been standardised on white populations[81]. For significant numbers of black patients the standard neutrophil count thresholds did not permit clozapine use as the thresholds did not take BEN into account.Since 2002, clozapine monitoring services in the UK have used reference ranges 0.5 × 109/l lower for patients with haematologically confirmed BEN and similar adjustments are available in the current US criteria, although with lower permissible minima.[82] [83] The Duffy–Null polymorphism, which protects against some types of malaria, is predictive of BEN[84]

Adverse effects

Clozapine may cause serious and potentially fatal adverse effects. Common effects include constipation, bed-wetting, night-time drooling, muscle stiffness, sedation, tremors, orthostatic hypotension, hyperglycemia, and weight gain. The risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms, such as tardive dyskinesia, is below that of typical antipsychotics; this may be due to clozapine's anticholinergic effects. Extrapyramidal symptoms may subside somewhat after a person switches from another antipsychotic to clozapine.[85]

Clozapine carries five black box warnings, including (1) severe neutropenia (low levels of neutrophils), (2) orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure upon changing positions), including slow heart rate and fainting, (3) seizures, (4) myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), and (5) risk of death when used in elderly people with dementia-related psychosis.[3] Lowering of the seizure threshold may be dose related. Increasing the dose slowly may decrease the risk for seizures and orthostatic hypotension.[86]

Many males have experienced cessation of ejaculation during orgasm as a side effect of clozapine, though this is not documented in official drug guides.[87]

However, many side-effects can be managed and may not warrant discontinuation.[88]

Agranulocytosis

Agranulocytosis is a severe decrease in the amount of a specific kind of white blood cell called granulocytes. Clozapine carries a black box warning for drug-induced agranulocytosis. Without monitoring, agranulocytosis occurs in about 1% of people who take clozapine during the first few months of treatment;[89] the risk of developing it is highest within the first three months of treatment and decreases substantially to less than 0.01% after one year.[90] People that take clozapine undergo routine absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring (neutrophils are the most abundant of the granulocytes); for example, in the United States, the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for clozapine involves routine ANC monitoring.[91]

Rapid point-of-care tests may simplify the monitoring for agranulocytosis.[92]

A clozapine "rechallenge" is when someone that experienced agranulocytosis while taking clozapine starts taking the medication again. Early findings suggest that the concurrent use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) to maintain the neutrophil count during a clozapine rechallenge is safe and effective. However, if agranulocytosis still occurs during a rechallenge, the alternative options are limited.[93][94]

Cardiac toxicity

Myocarditis is a sometimes fatal effect of clozapine, which usually develops within the first month of commencement.[95] First manifestations of illness are fever which may be accompanied by symptoms associated with upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal or urinary tract infection. Typically C-reactive protein (CRP) increases with the onset of fever and rises in the cardiac enzyme, troponin, occur up to 5 days later. Monitoring guidelines advise checking CRP and troponin at baseline and weekly for the first 4 weeks after clozapine initiation and observing the patient for signs and symptoms of illness.[96] Signs of heart failure are less common and may develop with the rise in troponin. A recent case-control study found that the risk of clozapine-induced myocarditis is increased with increasing rate of clozapine dose titration, increasing age and concomitant sodium valproate.[97]

Gastrointestinal hypomotility

Another underrecognized and potentially life-threatening effect spectrum is gastrointestinal hypomotility, which may manifest as severe constipation, fecal impaction, paralytic ileus, bowel obstruction, acute megacolon, ischemia or necrosis.[98] Colonic hypomotility has been shown to occur in up to 80% of people prescribed clozapine when gastrointestinal function is measured objectively using radiopaque markers.[99] Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility currently has a higher mortality rate than the better known side effect of agranulocytosis.[100] A Cochrane review found little evidence to help guide decisions about the best treatment for gastrointestinal hypomotility caused by clozapine and other antipsychotic medication.[101] Monitoring bowel function and the preemptive use of laxatives for all clozapine-treated people has been shown to improve colonic transit times and reduce serious sequelae.[102]

Hypersalivation

Hypersalivation, or the excessive production of saliva, is one of the most common adverse effects of clozapine (30-80%).[103] The saliva production is especially bothersome at night and first thing in the morning, as the immobility of sleep precludes the normal clearance of saliva by swallowing that occurs throughout the day.[103] While clozapine is a muscarinic antagonist at the M1, M2, M3, and M5 receptors, clozapine is a full agonist at the M4 subset. Because M4 is highly expressed in the salivary gland, its M4 agonist activity is thought to be responsible for hypersalivation.[104] Clozapine-induced hypersalivation is likely a dose-related phenomenon, and tends to be worse when first starting the medication.[103] Besides decreasing the dose or slowing the initial dose titration, other interventions that have shown some benefit include systemically-absorbed anticholinergic medications like diphenhydramine[103] and topical anticholinergic medications like ipratropium bromide.[105] Mild hypersalivation may be managed by sleeping with a towel over the pillow at night.[105]

Central nervous system

CNS side effects include drowsiness, vertigo, headache, tremor, syncope, sleep disturbances, nightmares, restlessness, akinesia, agitation, seizures, rigidity, akathisia, confusion, fatigue, insomnia, hyperkinesia, weakness, lethargy, ataxia, slurred speech, depression, myoclonic jerks, and anxiety. Rarely seen are delusions, hallucinations, delirium, amnesia, libido increase or decrease, paranoia and irritability, abnormal EEG, worsening of psychosis, paresthesia, status epilepticus, and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Similar to other antipsychotics clozapine rarely has been known to cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[106]

Urinary incontinence

Clozapine is linked to urinary incontinence,[107] though its appearance may be under-recognized.[108]

Withdrawal effects

Abrupt withdrawal may lead to cholinergic rebound effects, such as indigestion, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, overabundance of saliva, profuse sweating, insomnia, and agitation.[109] Abrupt withdrawal can also cause severe movement disorders, catatonia, and psychosis.[110] Doctors have recommended that patients, families, and caregivers be made aware of the symptoms and risks of abrupt withdrawal of clozapine. When discontinuing clozapine, gradual dose reduction is recommended to reduce the intensity of withdrawal effects.[111][112]

Weight gain and diabetes

In addition to hyperglycemia, significant weight gain is frequently experienced by patients treated with clozapine.[113] Impaired glucose metabolism and obesity have been shown to be constituents of the metabolic syndrome and may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. The data suggest that clozapine may be more likely to cause adverse metabolic effects than some of the other atypical antipsychotics.[114]

Overdose

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

Fatalities have been reported due to clozapine overdose, though overdoses > 4000 mg have been survived.[115]

Drug interactions

Fluvoxamine inhibits the metabolism of clozapine leading to significantly increased blood levels of clozapine.[116]

When carbamazepine is concurrently used with clozapine, it has been shown to decrease plasma levels of clozapine significantly thereby decreasing the beneficial effects of clozapine.[117][118] Patients should be monitored for "decreased therapeutic effects of clozapine if carbamazepine" is started or increased. If carbamazepine is discontinued or the dose of carbamazepine is decreased, therapeutic effects of clozapine should be monitored. The study recommends carbamazepine to not be used concurrently with clozapine due to increased risk of agranulocytosis.[119]

Ciprofloxacin is an inhibitor of CYP1A2 and clozapine is a major CYP1A2 substrate. Randomized study reported elevation in clozapine concentration in subjects concurrently taking ciprofloxacin.[120] Thus, the prescribing information for clozapine recommends "reducing the dose of clozapine by one-third of original dose" when ciprofloxacin and other CYP1A2 inhibitors are added to therapy, but once ciprofloxacin is removed from therapy, it is recommended to return clozapine to original dose.[121]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Protein | CZP Ki (nM) | NDMC Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 123.7 | 13.9 |

| 5-HT1B | 519 | 406.8 |

| 5-HT1D | 1,356 | 476.2 |

| 5-HT2A | 5.35 | 10.9 |

| 5-HT2B | 8.37 | 2.8 |

| 5-HT2C | 9.44 | 11.9 |

| 5-HT3 | 241 | 272.2 |

| 5-HT5A | 3,857 | 350.6 |

| 5-HT6 | 13.49 | 11.6 |

| 5-HT7 | 17.95 | 60.1 |

| α1A | 1.62 | 104.8 |

| α1B | 7 | 85.2 |

| α2A | 37 | 137.6 |

| α2B | 26.5 | 95.1 |

| α2C | 6 | 117.7 |

| β1 | 5,000 | 6,239 |

| β2 | 1,650 | 4,725 |

| D1 | 266.25 | 14.3 |

| D2 | 157 | 101.4 |

| D3 | 269.08 | 193.5 |

| D4 | 26.36 | 63.94 |

| D5 | 255.33 | 283.6 |

| H1 | 1.13 | 3.4 |

| H2 | 153 | 345.1 |

| H3 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| H4 | 665 | 1,028 |

| M1 | 6.17 | 67.6 |

| M2 | 36.67 | 414.5 |

| M3 | 19.25 | 95.7 |

| M4 | 15.33 | 169.9 |

| M5 | 15.5 | 35.4 |

| SERT | 1,624 | 316.6 |

| NET | 3,168 | 493.9 |

| DAT | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. All data are for cloned human proteins.[122][123] | ||

Clozapine is classified as an atypical antipsychotic drug because it binds to serotonin as well as dopamine receptors.[124]

Clozapine is an antagonist at the 5-HT2A subunit of the serotonin receptor, putatively improving depression, anxiety, and the negative cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia.[125][126]

A direct interaction of clozapine with the GABAB receptor has also been shown.[127] GABAB receptor-deficient mice exhibit increased extracellular dopamine levels and altered locomotor behaviour equivalent to that in schizophrenia animal models.[128] GABAB receptor agonists and positive allosteric modulators reduce the locomotor changes in these models.[129]

Clozapine induces the release of glutamate and D-serine, an agonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, from astrocytes,[130] and reduces the expression of astrocytic glutamate transporters. These are direct effects that are also present in astrocyte cell cultures not containing neurons. Clozapine prevents impaired NMDA receptor expression caused by NMDA receptor antagonists.[131]

Pharmacokinetics

The absorption of clozapine is almost complete following oral administration, but the oral bioavailability is only 60 to 70% due to first-pass metabolism. The time to peak concentration after oral dosing is about 2.5 hours, and food does not appear to affect the bioavailability of clozapine. However, it was shown that co-administration of food decreases the rate of absorption.[132] The elimination half-life of clozapine is about 14 hours at steady state conditions (varying with daily dose).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Clozapine is extensively metabolized in the liver, via the cytochrome P450 system, to polar metabolites suitable for elimination in the urine and feces. The major metabolite, norclozapine (desmethyl-clozapine), is pharmacologically active. The cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 1A2 is primarily responsible for clozapine metabolism, but 2C, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A3/4 appear to play roles as well. Agents that induce (e.g., cigarette smoke) or inhibit (e.g., theophylline, ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamine) CYP1A2 may increase or decrease, respectively, the metabolism of clozapine. For example, the induction of metabolism caused by smoking means that smokers require up to double the dose of clozapine compared with non-smokers to achieve an equivalent plasma concentration.[133]

Clozapine and norclozapine (desmethyl-clozapine) plasma levels may also be monitored, though they show a significant degree of variation and are higher in women and increase with age.[134] Monitoring of plasma levels of clozapine and norclozapine has been shown to be useful in assessment of compliance, metabolic status, prevention of toxicity, and in dose optimisation.[133]

Chemistry

Clozapine is a dibenzodiazepine that is structurally related to loxapine. It is slightly soluble in water, soluble in acetone, and highly soluble in chloroform. Its solubility in water is 0.1889 mg/L (25 °C).[4] Its manufacturer, Novartis, claims a solubility of <0.01% in water (<100 mg/L).[135]

Synthesis

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

Detection in body fluids

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

History[136]

Clozapine was synthesized in 1956[137] by Wander AG, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, based on the chemical structure of the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine. The first test in humans in 1962 was considered a failure. Trials in Germany in 1965 and 1966 as well as a trial in Vienna in 1966 were successful. In 1967 Wander AG was acquired by Sandoz.[138] Further trials took place in 1972 when clozapine was released in Switzerland and Austria as Leponex. Two years later it was released in West Germany, and Finland in 1975. Early testing was performed in the United States around the same time.[138] In 1975 16 cases of agranulocytosis leading to 8 deaths in clozapine-treated patients were reported from 6 hospitals, mostly in southwestern Finland led to concern.[139] Analysis of the Finnish cases revealed that all the agranulocytosis cases had occurred within the first 18 weeks of treatment and the authors proposed blood monitoring during this period.[140] The rate of agranulocytosis in Finland appeared to be 20 times higher than in the rest of the world and there was speculation that this may have been due a unique genetic diversity in the region.[141][142][143] Whilst the drug continued to be manufactured by Sandoz and remained available in Europe development in the U.S. halted.

Interest in clozapine continued in an investigational capacity in the United States because even in the 1980's the duration of hospitalisation, especially in State Hospitals for those with treatment resistant schizophrenia might often be measured in years rather than days.[144] The role of clozapine in treatment resistant schizophrenia was established by the landmark Clozaril Collaborative Study Group Study #30 in which clozapine showed marked benefits compared to chlorpromazine in a group of patients with protracted psychosis and who had already shown an inadequate response to other antipsychotics. This involved both stringent blood monitoring and a double blind design with power to demonstrate superiority over standard antipsychotic treatment. The inclusion criteria were patients who had failed to respond to at least three previous antipsychotics and had then not responded to a single blind treatment with haloperidol (mean dose 61mg +/- 14mg/d). Two hundred and sixty eight were randomised were to double blind trials of clozapine (upto 900 mg/d) or chlorpromazine (upto 1800mg/d). 30% of the clozapine patients responded compared to 4% of the controls, with significantly greater improvement on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression Scale, and Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation; this improvement included "negative" as well as positive symptom areas.[16] Following this study 1990,[needs copy edit] the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use. Cautious of this risk, however, the FDA required a black box warning for specific side effects including agranulocytosis, and took the unique step of requiring patients to be registered in a formal system of tracking so that blood count levels could be evaluated on a systematic basis.[143][145]

In December 2002, clozapine was approved in the US for reducing the risk of suicide in schizophrenic or schizoaffective patients judged to be at chronic risk for suicidal behavior.[146] In 2005, the FDA approved criteria to allow reduced blood monitoring frequency.[147] In 2015, the individual manufacturer Patient Registries were consolidated by request of the FDA into a single shared Patient Registry Called The Clozapine REMS Registry.[148] Despite the demonstrated safety of the new FDA monitoring requirements, which have lower neutrophil levels and no not include total white cell counts, international monitoring has not been standardised.[149][150][151]

Society and culture

| A | Alemoxan, Azaleptine, Azaleptol |

| C | Cloment, Clonex, Clopin, Clopine, Clopsine, Cloril, Clorilex, Clozamed, Clozapex, Clozapin, Clozapina, Clozapinum, Clozapyl, Clozarem, Clozaril |

| D | Denzapine, Dicomex |

| E | Elcrit, Excloza |

| F | FazaClo, Froidir |

| I | Ihope |

| K | Klozapol |

| L | Lanolept, Lapenax, Leponex, Lodux, Lozapine, Lozatric, Luften |

| M | Medazepine, Mezapin |

| N | Nemea, Nirva |

| O | Ozadep, Ozapim |

| R | Refract, Refraxol |

| S | Sanosen, Schizonex, Sensipin, Sequax, Sicozapina, Sizoril, Syclop, Syzopin |

| T | Tanyl |

| U | Uspen |

| V | Versacloz |

| X | Xenopal |

| Z | Zaclo, Zapenia, Zapine, Zaponex, Zaporil, Ziproc, Zopin |

Economics

Despite the expense of the risk monitoring and management systems required clozapine use is highly cost effective with a number of studies suggesting savings of tens of thousands of dollars per patient per year compared to other antipsychotics as well as advantages regarding improvements in quality of life. [152][153][154]Clozapine is available as a generic medication.[25]

Clozapine in the arts

Carrie Mathison, a fictional CIA operative in the television series Homeland secretly takes clozapine supplied by her sister for the treatment of bipolar affective disorder.

In the film Out of Darkness Diana Ross played the protagonist Paulie Cooper, 'a paranoid schizophrenic' who is depicted as having a dramatic improvement on clozapine.

References

- ^ a b c "Clozapine International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Clozaril- clozapine tablet". DailyMed. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ a b Hopfinger A, Esposito EX, Llinas A, Glen RC, Goodman JM (2009). "Findings of the Challenge To Predict Aqueous Solubility". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 49 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1021/ci800436c. PMID 19117422.

- ^ author., Stahl, Stephen M., 1951-. The clozapine handbook. ISBN 978-1-108-44746-1. OCLC 1222779588.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Clozaril 25 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ a b author., National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Great Britain),. Parkinson's disease in adults : diagnosis and management : full guideline. OCLC 1105250833.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. (July 2012). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 13 (5): 318–78. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.696143. PMID 22834451.

- ^ a b Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. (January 2010). "The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 71–93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp116. PMC 2800144. PMID 19955390.

- ^ a b Gaebel W, Weinmann S, Sartorius N, Rutz W, McIntyre JS (September 2005). "Schizophrenia practice guidelines: international survey and comparison". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 187 (3): 248–55. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.3.248. PMID 16135862.

- ^ a b Kuipers E, Yesufu-Udechuku A, Taylor C, Kendall T (February 2014). "Management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance". BMJ. 348: g1173. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1173. PMID 24523363.

- ^ a b Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJ, Birnbaum ML, et al. (March 2017). "Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group Consensus Guidelines on Diagnosis and Terminology". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 174 (3): 216–229. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503. PMC 6231547. PMID 27919182.

- ^ a b Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey E, et al. (May 2016). "Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (5): 410–72. doi:10.1177/0004867416641195. PMID 27106681.

- ^ Griffith, R.W.; Saameli, K. (October 1975). "CLOZAPINE AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS". The Lancet. 306 (7936): 657. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90135-X.

- ^ Crilly, John (1 March 2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. ISSN 0957-154X.

- ^ a b Kane, John (1 September 1988). "Clozapine for the Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenic: A Double-blind Comparison With Chlorpromazine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (9): 789. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ^ Taipale, Heidi; Tanskanen, Antti; Mehtälä, Juha; Vattulainen, Pia; Correll, Christoph U.; Tiihonen, Jari (2020-02). "20‐year follow‐up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20)". World Psychiatry. 19 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1002/wps.20699. ISSN 1723-8617. PMC 6953552. PMID 31922669.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Masuda, Takahiro; Misawa, Fuminari; Takase, Masayuki; Kane, John M.; Correll, Christoph U. (1 October 2019). "Association With Hospitalization and All-Cause Discontinuation Among Patients With Schizophrenia on Clozapine vs Other Oral Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies". JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (10): 1052. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1702. ISSN 2168-622X. PMC 6669790. PMID 31365048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b Myles N, Myles H, Xia S, Large M, Kisely S, Galletly C, et al. (August 2018). "Meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine-associated neutropenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 138 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1111/acps.12898. PMID 29786829.

- ^ Nielsen J, Young C, Ifteni P, Kishimoto T, Xiang YT, Schulte PF, et al. (February 2016). "Worldwide Differences in Regulations of Clozapine Use". CNS Drugs. 30 (2): 149–61. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1. PMID 26884144.

- ^ Whiskey E, Dzahini O, Ramsay R, O'Flynn D, Mijovic A, Gaughran F, et al. (September 2019). "Need to bleed? Clozapine haematological monitoring approaches a time for change". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 34 (5): 264–268. doi:10.1097/yic.0000000000000258. PMID 30882426.

- ^ Li XH, Zhong XM, Lu L, Zheng W, Wang SB, Rao WW, et al. (March 2020). "The prevalence of agranulocytosis and related death in clozapine-treated patients: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies". Psychological Medicine. 50 (4): 583–594. doi:10.1017/s0033291719000369. PMID 30857568.

- ^ Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S, Mousavi SS, Pasichnyk D, Newton AS (October 2012). "Antipsychotics in adults with schizophrenia: comparative effectiveness of first-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (7): 498–511. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00525. PMID 22893011.

- ^ "Clozaril, Fazaclo ODT, Versacloz (clozapine): Drug Safety Communication - FDA Strengthens Warning That Untreated Constipation Can Lead to Serious Bowel Problems". FDA. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Clozapine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Pardis, Parnian; Remington, Gary; Panda, Roshni; Lemez, Milan; Agid, Ofer (2019-10). "Clozapine and tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33 (10): 1187–1198. doi:10.1177/0269881119862535. ISSN 0269-8811.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Essali, Adib; Al-Haj Haasan, Nahla; Li, Chunbo; Rathbone, John (21 January 2009). Cochrane Schizophrenia Group (ed.). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2. PMC 7065592. PMID 19160174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Siskind, Dan; McCartney, Lara; Goldschlager, Romi; Kisely, Steve (2016-11). "Clozapine v . first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Psychiatry. 209 (5): 385–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. ISSN 0007-1250.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kahn, René S; Winter van Rossum, Inge; Leucht, Stefan; McGuire, Philip; Lewis, Shon W; Leboyer, Marion; Arango, Celso; Dazzan, Paola; Drake, Richard; Heres, Stephan; Díaz-Caneja, Covadonga M (2018-10). "Amisulpride and olanzapine followed by open-label treatment with clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder (OPTiMiSE): a three-phase switching study". The Lancet Psychiatry. 5 (10): 797–807. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30252-9.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Masuda T, Misawa F, Takase M, Kane JM, Correll CU (October 2019). "Association With Hospitalization and All-Cause Discontinuation Among Patients With Schizophrenia on Clozapine vs Other Oral Second-Generation Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies". JAMA Psychiatry. 76 (10): 1052–1062. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1702. PMC 6669790. PMID 31365048.

- ^ Nyakyoma K, Morriss R (2010). "Effectiveness of clozapine use in delaying hospitalization in routine clinical practice: a 2 year observational study". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 43 (2): 67–81. PMID 21052043.

- ^ Siskind D, Reddel T, MacCabe JH, Kisely S (June 2019). "The impact of clozapine initiation and cessation on psychiatric hospital admissions and bed days: a mirror image cohort study". Psychopharmacology. 236 (6): 1931–1935. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-5179-6. PMID 30715572.

- ^ Gaszner P, Makkos Z (May 2004). "Clozapine maintenance therapy in schizophrenia". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 28 (3): 465–9. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.011. PMID 15093952.

- ^ Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Mehtälä J, Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tiihonen J (February 2020). "20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20)". World Psychiatry. 19 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1002/wps.20699. PMC 6953552. PMID 31922669.

- ^ Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, Haukka J (August 2009). "11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study)". Lancet. 374 (9690): 620–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. PMID 19595447.

- ^ Taipale H, Lähteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tiihonen J (January 2021). "Comparative Effectiveness of Antipsychotics for Risk of Attempted or Completed Suicide Among Persons With Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa111. PMC 7824993. PMID 33428766.

- ^ Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, Romero-Ureclay JL, Ross CC, Gupta N, et al. (October 2014). "Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital". CNS Spectrums. 19 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1017/S1092852914000157. PMC 4255317. PMID 24698103.

- ^ Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, Bark N, Cooper TB (June 2006). "Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (6): 622–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.622. PMID 16754835.

- ^ Dalal B, Larkin E, Leese M, Taylor PJ (June 1999). "Clozapine treatment of long-standing schizophrenia and serious violence: a two-year follow-up study of the first 50 patients treated with clozapine in Rampton high security hospital". Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 9 (2): 168–178. doi:10.1002/cbm.304. ISSN 0957-9664.

- ^ Topiwala A, Fazel S (January 2011). "The pharmacological management of violence in schizophrenia: a structured review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1586/ern.10.180. PMID 21158555.

- ^ Frogley C, Taylor D, Dickens G, Picchioni M (October 2012). "A systematic review of the evidence of clozapine's anti-aggressive effects". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (9): 1351–71. doi:10.1017/S146114571100201X. PMID 22339930.

- ^ Thomson, Lindsay D. G. (2000-07). "Management of schizophrenia in conditions of high security". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (4): 252–260. doi:10.1192/apt.6.4.252. ISSN 1355-5146.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Silva, Edward; Till, Alex; Adshead, Gwen (2017-07). "Ethical dilemmas in psychiatry: When teams disagree". BJPsych Advances. 23 (4): 231–239. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016147. ISSN 2056-4678.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Silva, Edward; Higgins, Melanie; Hammer, Barbara; Stephenson, Paul (5 June 2020). "Clozapine rechallenge and initiation despite neutropenia- a practical, step-by-step guide". BMC Psychiatry. 20 (1). doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02592-2. ISSN 1471-244X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Till, Alex; Selwood, James; Silva, Edward (18 September 2018). "The assertive approach to clozapine: nasogastric administration". BJPsych Bulletin. 43 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.61. ISSN 2056-4694.

- ^ FISHER, WILLIAM A. (2003-01). "Elements of Successful Restraint and Seclusion Reduction Programs and Their Application in a Large, Urban, State Psychiatric Hospital". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00003. ISSN 1538-1145.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kasinathan, John; Mastroianni, Tony (2007-12). "Evaluating the use of enforced clozapine in an Australian forensic psychiatric setting: two cases". BMC Psychiatry. 7 (S1). doi:10.1186/1471-244x-7-s1-p13. ISSN 1471-244X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Swinton, Mark; Haddock, Andrew (2000-01). "Clozapine in Special Hospital: a retrospective case-control study". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 11 (3): 587–596. doi:10.1080/09585180010006205. ISSN 0958-5184.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Silva, Edward; Higgins, Melanie; Hammer, Barbara; Stephenson, Paul (1 January 2021). "Clozapine re-challenge and initiation following neutropenia: a review and case series of 14 patients in a high-secure forensic hospital". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 11: 20451253211015070. doi:10.1177/20451253211015070. ISSN 2045-1253. PMC 8221694. PMID 34221348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ "Schizophrenia, Violence, Clozapine and Risperidone: a Review". British Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (S31): 21–30. 1996-12. doi:10.1192/s0007125000298589. ISSN 0007-1250.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Swinton, Mark (2001-01). "Clozapine in severe borderline personality disorder". The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 12 (3): 580–591. doi:10.1080/09585180110091994. ISSN 0958-5184.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Haw, Camilla; Stubbs, Jean (2011-11). "Medication for borderline personality disorder: A survey at a secure hospital". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 15 (4): 270–274. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.590211. ISSN 1365-1501.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Brown, Darcy; Larkin, Fintan; Sengupta, Samrat; Romero-Ureclay, Jose L.; Ross, Callum C.; Gupta, Nitin; Vinestock, Morris; Das, Mrigendra (3 April 2014). "Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital". CNS Spectrums. 19 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1017/s1092852914000157. ISSN 1092-8529.

- ^ Silva, Edward; Till, Alex; Adshead, Gwen (2017-07). "Ethical dilemmas in psychiatry: When teams disagree". BJPsych Advances. 23 (4): 231–239. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016147. ISSN 2056-4678.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Henry, Rebecca; Massey, Ruth; Morgan, Kathy; Deeks, Johanne; Macfarlane, Hannah; Holmes, Nikki; Silva, Edward (2020-12). "Evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of intramuscular clozapine injection: illustrative case series". BJPsych Bulletin. 44 (6): 239–243. doi:10.1192/bjb.2020.6. ISSN 2056-4694. PMC 7684781. PMID 32081110.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Till, Alex; Selwood, James; Silva, Edward (2019-02). "The assertive approach to clozapine: nasogastric administration". BJPsych Bulletin. 43 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1192/bjb.2018.61. ISSN 2056-4694. PMC 6327298. PMID 30223913.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Casetta, Cecilia; Oloyede, Ebenezer; Whiskey, Eromona; Taylor, David Michael; Gaughran, Fiona; Shergill, Sukhi S.; Onwumere, Juliana; Segev, Aviv; Dzahini, Olubanke; Legge, Sophie E.; MacCabe, James Hunter (1 July 2020). "A retrospective study of intramuscular clozapine prescription for treatment initiation and maintenance in treatment-resistant psychosis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 217 (3): 506–513. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.115. ISSN 0007-1250.

- ^ Makar, A. B.; McMartin, K. E.; Palese, M.; Tephly, T. R. (1975-06). "Formate assay in body fluids: application in methanol poisoning". Biochemical Medicine. 13 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1016/0006-2944(75)90147-7. ISSN 0006-2944. PMID 1.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lokshin, Pavel; Lerner, Vladimir; Miodownik, Chanoch; Dobrusin, Michael; Belmaker, Robert H. (1999-10). "Parenteral Clozapine: Five Years of Experience". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (5): 479–480. doi:10.1097/00004714-199910000-00018. ISSN 0271-0749.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Schulte, Peter F.J.; Stienen, Juan J.; Bogers, Jan; Cohen, Dan; van Dijk, Daniel; Lionarons, Wendell H.; Sanders, Sophia S.; Heck, Adolph H. (2007-11). "Compulsory treatment with clozapine: A retrospective long-term cohort study". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 30 (6): 539–545. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.09.003. ISSN 0160-2527.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kasinathan, John; Mastroianni, Tony (2007-12). "Evaluating the use of enforced clozapine in an Australian forensic psychiatric setting: two cases". BMC Psychiatry. 7 (S1). doi:10.1186/1471-244x-7-s1-p13. ISSN 1471-244X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ McLean, Greg; Juckes, Lisa (1 December 2001). "Parenteral Clozapine (Clozaril)". Australasian Psychiatry. 9 (4): 371–371. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.0367a.x. ISSN 1039-8562.

- ^ FISHER, WILLIAM A. (2003-01). "Elements of Successful Restraint and Seclusion Reduction Programs and Their Application in a Large, Urban, State Psychiatric Hospital". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00003. ISSN 1538-1145.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mossman, Douglas; Lehrer, Douglas S. (2000-12). "Conventional and Atypical Antipsychotics and the Evolving Standard of Care". Psychiatric Services. 51 (12): 1528–1535. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1528. ISSN 1075-2730.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mistry, Himanshu; Osborn, David (2011-07). "Underuse of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 17 (4): 250–255. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.110.008128. ISSN 1355-5146.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stroup, T. Scott; Gerhard, Tobias; Crystal, Stephen; Huang, Cecelia; Olfson, Mark (2014-02). "Geographic and Clinical Variation in Clozapine Use in the United States". Psychiatric Services. 65 (2): 186–192. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300180. ISSN 1075-2730.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Downs, Johnny; Zinkler, Martin (2007-10). "Clozapine: national review of postcode prescribing". Psychiatric Bulletin. 31 (10): 384–387. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.106.013144. ISSN 0955-6036.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Purcell, Helen; Lewis, Shôn (2000-11). "Postcode prescribing in psychiatry". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (11): 420–422. doi:10.1192/pb.24.11.420. ISSN 0955-6036.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hayhurst, Karen P.; Brown, Petra; Lewis, Shôn W. (2003-04). "Postcode prescribing for schizophrenia". British Journal of Psychiatry. 182 (4): 281–283. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.4.281. ISSN 0007-1250.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nielsen, Jimmi; Røge, Rasmus; Schjerning, Ole; Sørensen, Holger J.; Taylor, David (2012-11). "Geographical and temporal variations in clozapine prescription for schizophrenia". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 22 (11): 818–824. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.03.003. ISSN 0924-977X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Latimer, Eric; Wynant, Willy; Clark, Robin; Malla, Ashok; Moodie, Erica; Tamblyn, Robyn; Naidu, Adonia (2013-04). "Underprescribing of Clozapine and Unexplained Variation in Use across Hospitals and Regions in the Canadian Province of Québec". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 7 (1): 33–41. doi:10.3371/csrp.lawy.012513. ISSN 1935-1232.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Whiskey, Eromona; Barnard, Alex; Oloyede, Ebenezer; Dzahini, Olubanke; Taylor, D.; Shergill, Sukhi (2020). "An Evaluation of the Variation and Underuse of Clozapine in the United Kingdom". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3716864. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ Kelly, Deanna L.; Kreyenbuhl, Julie; Dixon, Lisa; Love, Raymond C.; Medoff, Deborah; Conley, Robert R. (1 September 2007). "Clozapine Underutilization and Discontinuation in African Americans Due to Leucopenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (5): 1221–1224. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl068. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2632351. PMID 17170061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Mallinger, Julie B.; Fisher, Susan G.; Brown, Theodore; Lamberti, J. Steven (2006-01). "Racial Disparities in the Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics for the Treatment of Schizophrenia". Psychiatric Services. 57 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.133. ISSN 1075-2730.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Copeland, Laurel A.; Zeber, John E.; Valenstein, Marcia; Blow, Frederic C. (2003-10). "Racial Disparity in the Use of Atypical Antipsychotic Medications Among Veterans". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (10): 1817–1822. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1817. ISSN 0002-953X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kelly, Deanna L.; Dixon, Lisa B.; Kreyenbuhl, Julie A.; Medoff, Deborah; Lehman, Anthony F.; Love, Raymond C.; Brown, Clayton H.; Conley, Robert R. (15 September 2006). "Clozapine Utilization and Outcomes by Race in a Public Mental Health System: 1994-2000". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (09): 1404–1411. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0911. ISSN 0160-6689.

- ^ Whiskey, Eromona; Olofinjana, Olubanke; Taylor, David (19 March 2010). "The importance of the recognition of benign ethnic neutropenia in black patients during treatment with clozapine: case reports and database study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (6): 842–845. doi:10.1177/0269881110364267. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ^ Atallah-Yunes, Suheil Albert; Ready, Audrey; Newburger, Peter E. (2019-09). "Benign ethnic neutropenia". Blood Reviews. 37: 100586. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2019.06.003. PMC 6702066. PMID 31255364.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Haddy, Theresa B.; Rana, Sohail R.; Castro, Oswaldo (1999-01). "Benign ethnic neutropenia: What is a normal absolute neutrophil count?". Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 133 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1053/lc.1999.v133.a94931. ISSN 0022-2143.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Silva, Edward; Higgins, Melanie; Hammer, Barbara; Stephenson, Paul (1 January 2021). "Clozapine re-challenge and initiation following neutropenia: a review and case series of 14 patients in a high-secure forensic hospital". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 11: 20451253211015070. doi:10.1177/20451253211015070. ISSN 2045-1253. PMC 8221694. PMID 34221348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Nielsen, Jimmi; Young, Corina; Ifteni, Petru; Kishimoto, Taishiro; Xiang, Yu-Tao; Schulte, Peter F. J.; Correll, Christoph U.; Taylor, David (2016-02). "Worldwide Differences in Regulations of Clozapine Use". CNS Drugs. 30 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1. ISSN 1172-7047.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Reich, David; Nalls, Michael A.; Kao, W. H. Linda; Akylbekova, Ermeg L.; Tandon, Arti; Patterson, Nick; Mullikin, James; Hsueh, Wen-Chi; Cheng, Ching-Yu; Coresh, Josef; Boerwinkle, Eric (30 January 2009). "Reduced Neutrophil Count in People of African Descent Is Due To a Regulatory Variant in the Duffy Antigen Receptor for Chemokines Gene". PLoS Genetics. 5 (1): e1000360. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000360. ISSN 1553-7404.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Clozapine". Archived from the original on 10 November 2013.

- ^ "Clozapine". Archived from the original on 10 November 2013.

- ^ Baggaley M (April 2008). "Sexual dysfunction in schizophrenia: focus on recent evidence". Human Psychopharmacology. 23 (3): 201–209. doi:10.1002/hup.924. PMID 18338766. S2CID 30468671.

- ^ Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane JM (June 2013). "Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (6): 603–13. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08064. PMID 23842012.

- ^ Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of Psychosis and Maa". In Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2. OCLC 150149056.

- ^ Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Schwimmer JL, Schaaf JA (July 1993). "Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 329 (3): 162–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199307153290303. PMID 8515788.

- ^ "A Guide for Patients and Caregivers: What You Need to Know About Clozapine and Neutropenia" (PDF). Clozapine REMS. Clozapine REMS Program. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Kalaria SN, Kelly DL (2019). "Development of point-of-care testing devices to improve clozapine prescribing habits and patient outcomes". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 15: 2365–2370. doi:10.2147/NDT.S216803. PMC 6708436. PMID 31692521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Myles N, Myles H, Clark SR, Bird R, Siskind D (October 2017). "Use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to prevent recurrent clozapine-induced neutropenia on drug rechallenge: A systematic review of the literature and clinical recommendations". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (10): 980–989. doi:10.1177/0004867417720516. PMID 28747065.

- ^ Lally J, Malik S, Krivoy A, et al. (October 2017). "The Use of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor in Clozapine Rechallenge: A Systematic Review". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 37 (5): 600–604. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000767. PMID 28817489. S2CID 41269943.

- ^ Haas SJ, Hill R, Krum H, Liew D, Tonkin A, Demos L, Stephan K, McNeil J (2007). "Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a review of 116 cases of suspected myocarditis associated with the use of clozapine in Australia during 1993–2003". Drug Safety. 30 (1): 47–57. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730010-00005. PMID 17194170. S2CID 1153693.

- ^ Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Topliss DJ, McNeil JJ (June 2011). "A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 45 (6): 458–465. doi:10.3109/00048674.2011.572852. PMID 21524186. S2CID 26627093.

- ^ Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Topliss DJ, Wolfe R, McNeil JJ (November 2012). "Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: a case-control study". Schizophrenia Research. 141 (2–3): 173–8. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.018. PMID 23010488. S2CID 25720157.

- ^ Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, Harrison-Woolrych M (May 2008). "Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (5): 759–768. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0509. PMID 18452342.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Nowitz M, Stanley J, Grant E, Huthwaite M, Dunn H, Ellis, PM (March 2016). "Clozapine-treated patients have marked gastrointestinal hypomotility, the probable basis of life-threatening gastrointestinal complications: a cross sectional study". EBioMedicine. 5: 125–134. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.020. PMC 4816835. PMID 27077119.

- ^ Cohen D, Bogers JP, van Dijk D, Bakker B, Schulte PF (2012). "Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 73 (10): 1307–1312. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06977. PMID 23140648.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Newton-Howes G, Clarke MJ (24 January 2017). "Pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011128.pub2. PMC 6465073. PMID 28116777.

- ^ Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM, Nowitz M, Stanley J, Grant E, Huthwaite M, Dunn H (January 2017). "The Porirua Protocol in the treatment of clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility and constipation: A pre- and post-treatment study". CNS Drugs. 31 (1): 75–85. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0391-y. PMID 27826741. S2CID 46825178.

- ^ a b c d Syed R, Au K, Cahill C, Duggan L, He Y, Udu V, Xia J (July 2008). Syed R (ed.). "Pharmacological interventions for clozapine-induced hypersalivation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005579. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005579.pub2. PMC 4160791. PMID 18646130.

- ^ "Treatment of Clozapine-Induced Sialorrhea". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ a b Bird AM, Smith TL, Walton AE (May 2011). "Current treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (5): 667–75. doi:10.1345/aph.1P761. PMID 21540404. S2CID 42222976.

- ^ "ClozarilSide Effects & Drug Interactions". RxList. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Raja M (July 2011). "Clozapine safety, 35 years later". Current Drug Safety. 6 (3): 164–184. doi:10.2174/157488611797579230. PMID 22122392.

- ^ Barnes TR, Drake MJ, Paton C (January 2012). "Nocturnal enuresis with antipsychotic medication". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 200 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095737. PMID 22215862.

- ^ Stevenson E, Schembri F, Green DM, Burns JD (August 2013). "Serotonin syndrome associated with clozapine withdrawal". JAMA Neurology. 70 (8): 1054–5. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.95. PMID 23753931.

- ^ Wadekar M, Syed S (July 2010). "Clozapine-withdrawal catatonia". Psychosomatics. 51 (4): 355–355.e2. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.51.4.355. PMID 20587767.

- ^ Ahmed S, Chengappa KN, Naidu VR, Baker RW, Parepally H, Schooler NR (September 1998). "Clozapine withdrawal-emergent dystonias and dyskinesias: a case series". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 (9): 472–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v59n0906. PMID 9771818.

- ^ Szafrański T, Gmurkowski K (1999). "[Clozapine withdrawal. A review]". Psychiatria Polska. 33 (1): 51–67. PMID 10786215.

- ^ Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA, Goldstein D, Pashdag J, Mintz J, Marder SR (June 1999). "Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (6): 358–63. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0602. PMID 10401912.

- ^ Nasrallah HA (January 2008). "Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002066. PMID 17848919. S2CID 205678886.

- ^ Keck PE, McElroy SL (2002). "Clinical pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antimanic and mood-stabilizing medications". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (Suppl 4): 3–11. PMID 11913673.

- ^ Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, Hassan PC (December 1997). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 33 (6): 454–71. doi:10.2165/00003088-199733060-00004. PMID 9435993. S2CID 36883635.

- ^ Tiihonen J, Vartiainen H, Hakola P (January 1995). "Carbamazepine-induced changes in plasma levels of neuroleptics". Pharmacopsychiatry. 28 (1): 26–8. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979584. PMID 7746842.

- ^ Besag FM, Berry D (2006). "Interactions between antiepileptic and antipsychotic drugs". Drug Safety. 29 (2): 95–118. doi:10.2165/00002018-200629020-00001. PMID 16454538. S2CID 45735414.

- ^ Jerling M, Lindström L, Bondesson U, Bertilsson L (August 1994). "Fluvoxamine inhibition and carbamazepine induction of the metabolism of clozapine: evidence from a therapeutic drug monitoring service". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 16 (4): 368–74. doi:10.1097/00007691-199408000-00006. PMID 7974626. S2CID 31325882.

- ^ Raaska K, Neuvonen PJ (November 2000). "Ciprofloxacin increases serum clozapine and N-desmethylclozapine: a study in patients with schizophrenia". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 56 (8): 585–9. doi:10.1007/s002280000192. PMID 11151749. S2CID 20390680.

- ^ Prescribing information. Clozaril (clozapine). East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, September 2014.

- ^ a b Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Naheed M, Green B (2001). "Focus on clozapine". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 17 (3): 223–9. doi:10.1185/0300799039117069. PMID 11900316. S2CID 13021800.

- ^ Robinson DS (2007). "CNS Receptor Partial Agonists: A New Approach to Drug Discovery". Primary Psychiatry. 14 (8): 22–24. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Clozapine | C18H19ClN4". PubChem. U.S. Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Wu Y, Blichowski M, Daskalakis ZJ, Wu Z, Liu CC, Cortez MA, Snead OC (September 2011). "Evidence that clozapine directly interacts on the GABAB receptor". NeuroReport. 22 (13): 637–41. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e328349739b. PMID 21753741. S2CID 277293.

- ^ Vacher CM, Gassmann M, Desrayaud S, Challet E, Bradaia A, Hoyer D, Waldmeier P, Kaupmann K, Pévet P, Bettler B (May 2006). "Hyperdopaminergia and altered locomotor activity in GABAB1-deficient mice". Journal of Neurochemistry. 97 (4): 979–91. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03806.x. PMID 16606363. S2CID 19780444.

- ^ Wierońska JM, Kusek M, Tokarski K, Wabno J, Froestl W, Pilc A (July 2011). "The GABA B receptor agonist CGP44532 and the positive modulator GS39783 reverse some behavioural changes related to positive syndromes of psychosis in mice". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (5): 1034–47. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01301.x. PMC 3130949. PMID 21371011.

- ^ Tanahashi S, Yamamura S, Nakagawa M, Motomura E, Okada M (March 2012). "Clozapine, but not haloperidol, enhances glial D-serine and L-glutamate release in rat frontal cortex and primary cultured astrocytes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 165 (5): 1543–55. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01638.x. PMC 3372736. PMID 21880034.

- ^ Xi D, Li YC, Snyder MA, Gao RY, Adelman AE, Zhang W, Shumsky JS, Gao WJ (May 2011). "Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist ameliorates MK801-induced dysfunction of NMDA receptors via the Akt/GSK-3β pathway in adult rat prefrontal cortex". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (6): 1260–74. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.12. PMC 3079418. PMID 21326193.

- ^ Disanto AR, Golden G (1 August 2009). "Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of clozapine orally disintegrating tablet 12.5 mg: a randomized, open-label, crossover study in healthy male subjects". Clinical Drug Investigation. 29 (8): 539–49. doi:10.2165/00044011-200929080-00004. PMID 19591515. S2CID 45731786.

- ^ a b Rostami-Hodjegan A, Amin AM, Spencer EP, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Flanagan RJ (February 2004). "Influence of dose, cigarette smoking, age, sex, and metabolic activity on plasma clozapine concentrations: a predictive model and nomograms to aid clozapine dose adjustment and to assess compliance in individual patients". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (1): 70–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000106221.36344.4d. PMID 14709950. S2CID 31923731.

- ^ Lane HY, Chang YC, Chang WH, Lin SK, Tseng YT, Jann MW (January 1999). "Effects of gender and age on plasma levels of clozapine and its metabolites: analyzed by critical statistics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (1): 36–40. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0108. PMID 10074876.

- ^ Novartis Pharmaceuticals (April 2006). "Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. p. 36. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ Kane, John (1 September 1988). "Clozapine for the Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenic: A Double-blind Comparison With Chlorpromazine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (9): 789. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ^ Haidary HA, Padhy RK (January 2019). "Clozapine". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30571020.

- ^ a b Crilly J (March 2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. PMID 17580753. S2CID 21086497.

- ^ Idänpään-Heikkilä, Juhana; Alhava, Eeva; Olkinuora, Martti; Palva, Ilmari (1975-09). "CLOZAPINE AND AGRANULOCYTOSIS". The Lancet. 306 (7935): 611. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90206-8. ISSN 0140-6736.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Amsler, H. A.; Teerenhovi, L.; Barth, E.; Harjula, K.; Vuopio, P. (1977-10). "Agranulocytosis in patients treated with clozapine.: A STUDY OF THE FINNISH EPIDEMIC". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 56 (4): 241–248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00224.x. ISSN 0001-690X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Griffith RW, Saameli K (October 1975). "Letter: Clozapine and agranulocytosis". Lancet. 2 (7936): 657. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90135-x. PMID 52022. S2CID 53296036.

- ^ Legge SE, Walters JT (March 2019). "Genetics of clozapine-associated neutropenia: recent advances, challenges and future perspective". Pharmacogenomics. 20 (4): 279–290. doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0188. PMC 6563116. PMID 30767710.

- ^ a b de With SA, Pulit SL, Staal WG, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA (July 2017). "More than 25 years of genetic studies of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis". The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 17 (4): 304–311. doi:10.1038/tpj.2017.6. PMID 28418011. S2CID 5007914.

- ^ Crilly, John (2007-03). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. ISSN 0957-154X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Healy D (8 May 2018). The Psychopharmacologists. doi:10.1201/9780203736159. ISBN 9780203736159.

- ^ "Supplemental NDA Approval Letter for Clozaril, NDA 19-758 / S-047" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. 18 December 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Letter to Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "FDA Modifies REMS Program for Clozapine". www.raps.org. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Sultan, Ryan S.; Olfson, Mark; Correll, Christoph U.; Duncan, Erica J. (25 October 2017). "Evaluating the Effect of the Changes in FDA Guidelines for Clozapine Monitoring". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 78 (8): e933–e939. doi:10.4088/jcp.16m11152. ISSN 0160-6689.

- ^ Nielsen, Jimmi; Young, Corina; Ifteni, Petru; Kishimoto, Taishiro; Xiang, Yu-Tao; Schulte, Peter F. J.; Correll, Christoph U.; Taylor, David (2016-02). "Worldwide Differences in Regulations of Clozapine Use". CNS Drugs. 30 (2): 149–161. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1. ISSN 1172-7047.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Oloyede, Ebenezer; Casetta, Cecilia; Dzahini, Olubanke; Segev, Aviv; Gaughran, Fiona; Shergill, Sukhi; Mijovic, Alek; Helthuis, Marinka; Whiskey, Eromona; MacCabe, James Hunter; Taylor, David (1 July 2021). "There Is Life After the UK Clozapine Central Non-Rechallenge Database". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 47 (4): 1088–1098. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbab006. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 8266568. PMID 33543755.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Oh, P. I.; Iskedjian, M.; Addis, A.; Lanctôt, K.; Einarson, T. R. (2001). "Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a cost-utility analysis". The Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology = Journal Canadien De Pharmacologie Clinique. 8 (4): 199–206. ISSN 1198-581X. PMID 11743592.

- ^ Jin, Huajie; Tappenden, Paul; MacCabe, James H.; Robinson, Stewart; Byford, Sarah (27 May 2020). "Evaluation of the Cost-effectiveness of Services for Schizophrenia in the UK Across the Entire Care Pathway in a Single Whole-Disease Model". JAMA Network Open. 3 (5): e205888. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5888. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 7254180. PMID 32459356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Morris, Stephen; Hogan, Thomas; McGuire, Alistair (1998). "The Cost-Effectiveness of Clozapine: A Survey of the Literature". Clinical Drug Investigation. 15 (2): 137–152. doi:10.2165/00044011-199815020-00007. ISSN 1173-2563.

Further reading

- Benkert O, Hippius H. Kompendium der Psychiatrischen Pharmakotherapie (in German) (4th ed.). Springer Verlag.

- Bandelow B, Bleich S, Kropp S. Handbuch Psychopharmaka (in German) (2nd ed.). Hogrefe.

- Crilly J (March 2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. PMID 17580753. S2CID 21086497.

- Dean L (2016). "Clozapine Therapy and CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4 Genotypes". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520368. Bookshelf ID: NBK367795.

External links

- "Clozapine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) requirements will change on November 15, 2021". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 July 2021.

- "Clozapine REMS Modification Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 July 2021.

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from September 2021

- Atypical antipsychotics

- Chloroarenes

- Dibenzodiazepines

- Novartis brands

- Dopamine agonists

- Dopamine antagonists

- GABA receptor antagonists

- Mood stabilizers

- Muscarinic agonists

- Muscarinic antagonists

- Piperazines

- Serotonin antagonists

- World Health Organization essential medicines