Propranolol: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| IUPAC_name = (''RS'')-1-(1-methylethylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy)propan-2-ol |

| IUPAC_name = (''RS'')-1-(1-methylethylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy)propan-2-ol |

||

| image = Propranolol.svg |

| image = Propranolol.svg |

||

| width = |

| width = 250px |

||

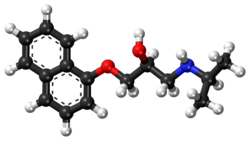

| image2 = Propranolol ball-and-stick model.png |

| image2 = Propranolol ball-and-stick model.png |

||

| width2 = |

| width2 = 250px |

||

| chirality = [[Racemic mixture]] |

| chirality = [[Racemic mixture]] |

||

<!--Clinical data--> |

<!--Clinical data--> |

||

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

===Pharmacodynamics=== |

===Pharmacodynamics=== |

||

{| class="wikitable floatright" style="font-size:small;" |

|||

|+ Propranolol<ref name="PDSP">{{cite web | title = PDSP K<sub>i</sub> Database | work = Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP) | author1 = Roth, BL | author2 = Driscol, J | publisher = University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health || format = HTML | accessdate = 14 August 2017 | url = https://kidbdev.med.unc.edu/databases/pdsp.php?knowID=0&kiKey=&receptorDD=&receptor=&speciesDD=&species=&sourcesDD=&source=&hotLigandDD=&hotLigand=&testLigandDD=&testFreeRadio=testFreeRadio&testLigand=propranolol&referenceDD=&reference=&KiGreater=&KiLess=&kiAllRadio=all&doQuery=Submit+Query}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! Site !! K<sub>i</sub> (nM) !! Species !! Ref |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT1A receptor|5-HT<sub>1A</sub>]] || 55–272 || Human || <ref name="pmid2078271">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hamon M, Lanfumey L, el Mestikawy S, Boni C, Miquel MC, Bolaños F, Schechter L, Gozlan H | title = The main features of central 5-HT1 receptors | journal = Neuropsychopharmacology | volume = 3 | issue = 5-6 | pages = 349–60 | year = 1990 | pmid = 2078271 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid9686407">{{cite journal | vauthors = Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, Schwartz RW, Haggart D, O'Brien A, White A, Kennedy JM, Craymer K, Farrington L, Auh JS | title = Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications | journal = NIDA Res. Monogr. | volume = 178 | issue = | pages = 440–66 | year = 1998 | pmid = 9686407 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT1B receptor|5-HT<sub>1B</sub>]] || 85 || Rat || <ref name="pmid2936965">{{cite journal | vauthors = Engel G, Göthert M, Hoyer D, Schlicker E, Hillenbrand K | title = Identity of inhibitory presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) autoreceptors in the rat brain cortex with 5-HT1B binding sites | journal = Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. | volume = 332 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–7 | year = 1986 | pmid = 2936965 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT1D receptor|5-HT<sub>1D</sub>]] || 4,070 || Pig || <ref name="pmid2797214">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schlicker E, Fink K, Göthert M, Hoyer D, Molderings G, Roschke I, Schoeffter P | title = The pharmacological properties of the presynaptic serotonin autoreceptor in the pig brain cortex conform to the 5-HT1D receptor subtype | journal = Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. | volume = 340 | issue = 1 | pages = 45–51 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2797214 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT2A receptor|5-HT<sub>2A</sub>]] || 4,280 || Human || <ref name="pmid2723656">{{cite journal | vauthors = Elliott JM, Kent A | title = Comparison of [125I]iodolysergic acid diethylamide binding in human frontal cortex and platelet tissue | journal = J. Neurochem. | volume = 53 | issue = 1 | pages = 191–6 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2723656 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT2C receptor|5-HT<sub>2C</sub>]] || 736–2,457 || Rodent || <ref name="pmid4078623">{{cite journal | vauthors = Yagaloff KA, Hartig PR | title = 125I-lysergic acid diethylamide binds to a novel serotonergic site on rat choroid plexus epithelial cells | journal = J. Neurosci. | volume = 5 | issue = 12 | pages = 3178–83 | year = 1985 | pmid = 4078623 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid9686407" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[5-HT3 receptor|5-HT<sub>3</sub>]] || >10,000 || Human || <ref name="pmid2809591">{{cite journal | vauthors = Barnes JM, Barnes NM, Costall B, Ironside JW, Naylor RJ | title = Identification and characterisation of 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 recognition sites in human brain tissue | journal = J. Neurochem. | volume = 53 | issue = 6 | pages = 1787–93 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2809591 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor|α<sub>1</sub>]] || {{abbr|ND|No data}} || {{abbr|ND|No data}} || {{abbr|ND|No data}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor|α<sub>2</sub>]] || 1,297–2,789 || Rat || <ref name="pmid2885406">{{cite journal | vauthors = Boyajian CL, Leslie FM | title = Pharmacological evidence for alpha-2 adrenoceptor heterogeneity: differential binding properties of [3H]rauwolscine and [3H]idazoxan in rat brain | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 241 | issue = 3 | pages = 1092–8 | year = 1987 | pmid = 2885406 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''[[Beta-1 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>1</sub>]]''' || '''0.02–2.69''' || '''Human''' || <ref name="pmid8935801">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, Luyten WH, Van Gompel P, Lesage AS, De Loore K, Leysen JE | title = Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding | journal = Psychopharmacology (Berl.) | volume = 124 | issue = 1-2 | pages = 57–73 | year = 1996 | pmid = 8935801 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid7915318">{{cite journal | vauthors = Fraundorfer PF, Fertel RH, Miller DD, Feller DR | title = Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of high-affinity trimetoquinol analogs on guinea pig and human beta adrenergic receptor subtypes: evidence for partial agonism | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 270 | issue = 2 | pages = 665–74 | year = 1994 | pmid = 7915318 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''[[Beta-2 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>2</sub>]]''' || '''0.01–0.61''' || '''Human''' || <ref name="pmid8935801" /><ref name="pmid7915318" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Beta-3 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>3</sub>]] || 450 || Mouse || <ref name="pmid1718744">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nahmias C, Blin N, Elalouf JM, Mattei MG, Strosberg AD, Emorine LJ | title = Molecular characterization of the mouse beta 3-adrenergic receptor: relationship with the atypical receptor of adipocytes | journal = EMBO J. | volume = 10 | issue = 12 | pages = 3721–7 | year = 1991 | pmid = 1718744 | pmc = 453106 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[D1 receptor|D<sub>1</sub>]] || >10,000 || Human || <ref name="pmid9686407" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[D2 receptor|D<sub>2</sub>]] || >10,000 || Human || <ref name="pmid9686407" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[H1 receptor|H<sub>1</sub>]] || >10,000 || Human || <ref name="pmid6146381">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kanba S, Richelson E | title = Histamine H1 receptors in human brain labelled with [3H]doxepin | journal = Brain Res. | volume = 304 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–7 | year = 1984 | pmid = 6146381 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{abbrlink|SERT|Serotonin transporter}} || 3,700 || Rat || <ref name="pmid2970277">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kovachich GB, Aronson CE, Brunswick DJ, Frazer A | title = Quantitative autoradiography of serotonin uptake sites in rat brain using [3H]cyanoimipramine | journal = Brain Res. | volume = 454 | issue = 1-2 | pages = 78–88 | year = 1988 | pmid = 2970277 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{abbrlink|NET|Norepinephrine transporter}} || 5,000 ({{abbrlink|IC<sub>50</sub>|Half-maximal inhibitory concentration}}) || Rat || <ref name="pmid2872325">{{cite journal | vauthors = Tuross N, Patrick RL | title = Effects of propranolol on catecholamine synthesis and uptake in the central nervous system of the rat | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 237 | issue = 3 | pages = 739–45 | year = 1986 | pmid = 2872325 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{abbrlink|DAT|Dopamine transporter}} || 29,000 ({{abbr|IC<sub>50</sub>|Half-maximal inhibitory concentration}}) || Rat || <ref name="pmid2872325" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{abbrlink|VDCC|Voltage-dependent calcium channel}} || >10,000 || Rat || <ref name="pmid2338642">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zobrist RH, Mecca TE | title = [3H]TA-3090, a selective benzothiazepine-type calcium channel receptor antagonist: in vitro characterization | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 253 | issue = 2 | pages = 461–5 | year = 1990 | pmid = 2338642 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

|||

|- class="sortbottom" |

|||

| colspan="4" style="width: 1px;" | Values are K<sub>i</sub> (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. |

|||

|} |

|||

Propranolol is classified as a non-cardioselective sympatholytic [[beta blocker]] that crosses the [[blood–brain barrier]]. It is lipid soluble and also has sodium channel blocking effects. Propranolol is a non-selective [[beta blocker]]; that is, it [[receptor antagonist|blocks]] the action of [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) and [[norepinephrine]] (noradrenaline) at both [[Beta-1 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>1</sub>-]] and [[Beta-2 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>2</sub>-adrenergic receptor]]s. It has little [[Beta blocker#Intrinsic sympathomimetic activity|intrinsic sympathomimetic activity]], but has strong [[membrane stabilizing effect|membrane stabilizing activity]] (only at high blood concentrations, e.g. [[overdose]]).{{Citation needed|date=May 2016}} Propranolol is able to cross the blood–brain barrier and exert effects in the [[central nervous system]] in addition to its peripheral activity.<ref name="Steenenvan Wijk2015">{{cite journal|last1=Steenen|first1=S. A.|last2=van Wijk|first2=A. J.|last3=van der Heijden|first3=G. J.|last4=van Westrhenen|first4=R.|last5=de Lange|first5=J.|last6=de Jongh|first6=A.|title=Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=Journal of Psychopharmacology|volume=30|issue=2|year=2015|pages=128–139|issn=0269-8811|doi=10.1177/0269881115612236|pmid=26487439|pmc=4724794}}</ref> |

Propranolol is classified as a non-cardioselective sympatholytic [[beta blocker]] that crosses the [[blood–brain barrier]]. It is lipid soluble and also has sodium channel blocking effects. Propranolol is a non-selective [[beta blocker]]; that is, it [[receptor antagonist|blocks]] the action of [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) and [[norepinephrine]] (noradrenaline) at both [[Beta-1 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>1</sub>-]] and [[Beta-2 adrenergic receptor|β<sub>2</sub>-adrenergic receptor]]s. It has little [[Beta blocker#Intrinsic sympathomimetic activity|intrinsic sympathomimetic activity]], but has strong [[membrane stabilizing effect|membrane stabilizing activity]] (only at high blood concentrations, e.g. [[overdose]]).{{Citation needed|date=May 2016}} Propranolol is able to cross the blood–brain barrier and exert effects in the [[central nervous system]] in addition to its peripheral activity.<ref name="Steenenvan Wijk2015">{{cite journal|last1=Steenen|first1=S. A.|last2=van Wijk|first2=A. J.|last3=van der Heijden|first3=G. J.|last4=van Westrhenen|first4=R.|last5=de Lange|first5=J.|last6=de Jongh|first6=A.|title=Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=Journal of Psychopharmacology|volume=30|issue=2|year=2015|pages=128–139|issn=0269-8811|doi=10.1177/0269881115612236|pmid=26487439|pmc=4724794}}</ref> |

||

In addition to blockade of [[adrenergic receptor]]s, propranolol has weak inhibitory effects on the [[norepinephrine transporter]] and/or weakly stimulates norepinephrine release (i.e., the concentration of norepinephrine is increased in the [[synapse]]).<ref name="YoungGlennon2008">{{cite journal|last1=Young|first1=Richard|last2=Glennon|first2=Richard A.|title=S(−)Propranolol as a discriminative stimulus and its comparison to the stimulus effects of cocaine in rats|journal=Psychopharmacology|volume=203|issue=2|year=2008|pages=369–382|issn=0033-3158|doi=10.1007/s00213-008-1317-2|pmid=18795268}}</ref><ref name="pmid2872325">{{cite journal | vauthors = Tuross N, Patrick RL | title = Effects of propranolol on catecholamine synthesis and uptake in the central nervous system of the rat | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 237 | issue = 3 | pages = 739–45 | year = 1986 | pmid = 2872325 | doi = | url = }}</ref> Since propranolol blocks β-adrenoceptors, the increase in synaptic norepinephrine only results in α-adrenoceptor activation, with the [[Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor|α<sub>1</sub>-adrenoceptor]] being particularly important for effects observed in [[animal model]]s.<ref name="YoungGlennon2008" /><ref name="pmid2872325" /> Therefore, it can be looked upon as a weak indirect α<sub>1</sub>-adrenoceptor [[agonist]] in addition to potent β-adrenoceptor antagonist.<ref name="YoungGlennon2008" /><ref name="pmid2872325" /> In addition to its effects on the adrenergic system, there is evidence that indicates that propranolol may |

In addition to blockade of [[adrenergic receptor]]s, propranolol has very weak inhibitory effects on the [[norepinephrine transporter]] and/or weakly stimulates norepinephrine release (i.e., the concentration of norepinephrine is increased in the [[synapse]]).<ref name="YoungGlennon2008">{{cite journal|last1=Young|first1=Richard|last2=Glennon|first2=Richard A.|title=S(−)Propranolol as a discriminative stimulus and its comparison to the stimulus effects of cocaine in rats|journal=Psychopharmacology|volume=203|issue=2|year=2008|pages=369–382|issn=0033-3158|doi=10.1007/s00213-008-1317-2|pmid=18795268}}</ref><ref name="pmid2872325">{{cite journal | vauthors = Tuross N, Patrick RL | title = Effects of propranolol on catecholamine synthesis and uptake in the central nervous system of the rat | journal = J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. | volume = 237 | issue = 3 | pages = 739–45 | year = 1986 | pmid = 2872325 | doi = | url = }}</ref> Since propranolol blocks β-adrenoceptors, the increase in synaptic norepinephrine only results in α-adrenoceptor activation, with the [[Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor|α<sub>1</sub>-adrenoceptor]] being particularly important for effects observed in [[animal model]]s.<ref name="YoungGlennon2008" /><ref name="pmid2872325" /> Therefore, it can be looked upon as a weak indirect α<sub>1</sub>-adrenoceptor [[agonist]] in addition to potent β-adrenoceptor antagonist.<ref name="YoungGlennon2008" /><ref name="pmid2872325" /> In addition to its effects on the adrenergic system, there is evidence that indicates that propranolol may act as a weak [[receptor antagonist|antagonist]] of certain [[serotonin receptor]]s, namely the [[5-HT1A|5-HT<sub>1A</sub>]] and [[5-HT1B receptor|5-HT<sub>1B</sub> receptor]]s.<ref name="pmid9064274">{{cite journal | vauthors = Davids E, Lesch KP | title = [The 5-HT1A receptor: a new effective principle in psychopharmacologic therapy?] | language = German | journal = Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr | volume = 64 | issue = 11 | pages = 460–72 | year = 1996 | pmid = 9064274 | doi = 10.1055/s-2007-996592 | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid7938165">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hoyer D, Clarke DE, Fozard JR, Hartig PR, Martin GR, Mylecharane EJ, Saxena PR, Humphrey PP | title = International Union of Pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) | journal = Pharmacol. Rev. | volume = 46 | issue = 2 | pages = 157–203 | year = 1994 | pmid = 7938165 | doi = | url = }}</ref> |

||

Both enantiomers of propranolol have a [[local anesthetic]] (topical) effect, which is normally mediated by blockade of [[voltage-gated sodium channel]]s. Studies have demonstrated propranolol's ability to block cardiac, neuronal, and skeletal voltage-gated sodium channels, accounting for its known membrane stabilizing effect and antiarrhythmic and other central nervous system effects.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Wang D. W. |author2=Mistry A. M. |author3=Kahlig K. M. |author4=Kearney J. A. |author5=Xiang J. |author6=George A. L. Jr | year = 2010 | title = Propranolol blocks cardiac and neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels | url = | journal = Front. Pharmacol | volume = 1 | issue = | page = 144 | doi = 10.3389/fphar.2010.00144 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Bankston J. R. |author2=Kass R. S. | year = 2010 | title = Molecular determinants of local anesthetic action of beta-blocking drugs: implications for therapeutic management of long QT syndrome variant 3 | url = | journal = J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol | volume = 48 | issue = | pages = 246–253 | doi=10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.05.012}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Desaphy J. F. |author2=Pierno S. |author3=De Luca A. |author4=Didonna P. |author5=Camerino D. C. | year = 2003 | title = Different ability of clenbuterol and salbutamol to block sodium channels predicts their therapeutic use in muscle excitability disorders | url = | journal = Mol. Pharmacol. | volume = 63 | issue = 3| pages = 659–670 | doi=10.1124/mol.63.3.659 | pmid=12606775}}</ref> |

Both enantiomers of propranolol have a [[local anesthetic]] (topical) effect, which is normally mediated by blockade of [[voltage-gated sodium channel]]s. Studies have demonstrated propranolol's ability to block cardiac, neuronal, and skeletal voltage-gated sodium channels, accounting for its known membrane stabilizing effect and antiarrhythmic and other central nervous system effects.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Wang D. W. |author2=Mistry A. M. |author3=Kahlig K. M. |author4=Kearney J. A. |author5=Xiang J. |author6=George A. L. Jr | year = 2010 | title = Propranolol blocks cardiac and neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels | url = | journal = Front. Pharmacol | volume = 1 | issue = | page = 144 | doi = 10.3389/fphar.2010.00144 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Bankston J. R. |author2=Kass R. S. | year = 2010 | title = Molecular determinants of local anesthetic action of beta-blocking drugs: implications for therapeutic management of long QT syndrome variant 3 | url = | journal = J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol | volume = 48 | issue = | pages = 246–253 | doi=10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.05.012}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Desaphy J. F. |author2=Pierno S. |author3=De Luca A. |author4=Didonna P. |author5=Camerino D. C. | year = 2003 | title = Different ability of clenbuterol and salbutamol to block sodium channels predicts their therapeutic use in muscle excitability disorders | url = | journal = Mol. Pharmacol. | volume = 63 | issue = 3| pages = 659–670 | doi=10.1124/mol.63.3.659 | pmid=12606775}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:10, 1 October 2017

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Inderal, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, rectal, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 26% |

| Metabolism | Liver (extensive) 1A2, 2D6; minor: 2C19, 3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 4–5 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (<1%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.618 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H21NO2 |

| Molar mass | 259.34 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Propranolol, sold under the brand name Inderal among others, is a medication of the beta blocker type.[2] It is used to treat high blood pressure, a number of types of irregular heart rate, thyrotoxicosis, capillary hemangiomas, performance anxiety, and essential tremors.[2][3][4] It is used to prevent migraine headaches, and to prevent further heart problems in those with angina or previous heart attacks.[2] It can be taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[2] The formulation that is taken by mouth comes in short acting and long acting versions.[2] Propranolol appears in the blood after 30 minutes and has a maximum effect between 60 and 90 minutes when taken by mouth.[2][5]

Common side effects include nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation.[2] It should not be used in those with an already slow heart rate and most of those with heart failure.[2] Quickly stopping the medication in those with coronary artery disease may worsen symptoms.[2] It may worsen the symptoms of asthma.[2] Greater care is recommended in those with liver or kidney problems.[2] Propranolol may cause harmful effects in the baby if taken during pregnancy.[6] Its use during breastfeeding is probably safe, but the baby should be monitored for side effects.[7] It is a non-selective beta blocker which works by blocking β-adrenergic receptors.[2]

Propranolol was discovered in 1964.[8][9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[10] Propranolol is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between US$0.24 and US$2.16 per month as of 2014.[11] In the United States it costs about 15 USD per month at a typical dose.[2]

Medical uses

Propranolol is used for treating various conditions, including:

Cardiovascular

- Hypertension

- Angina pectoris (with the exception of variant angina)

- Tachyarrhythmia

- Myocardial infarction

- Tachycardia (and other sympathetic nervous system symptoms, such as muscle tremor) associated with various conditions, including anxiety, panic, hyperthyroidism, and lithium therapy

- Portal hypertension, to lower portal vein pressure

- Prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding and ascites

- Anxiety

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

While once a first-line treatment for hypertension, the role for beta blockers was downgraded in June 2006 in the United Kingdom to fourth-line, as they do not perform as well as other drugs, particularly in the elderly, and evidence is increasing that the most frequently used beta blockers at usual doses carry an unacceptable risk of provoking type 2 diabetes.[12]

Propranolol is not recommended for the treatment of hypertension by the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) because a higher rate of the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke compared to an angiotensin receptor blocker was noted in one study.[13]

Psychiatric

Propranolol is occasionally used to treat performance anxiety.[3] Evidence to support its use in other anxiety disorders is poor.[14] Some experimentation has been conducted in other psychiatric areas:[15]

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and specific phobias (see subsection below)

- Aggressive behavior of patients with brain injuries[16]

- Treating the excessive drinking of fluids in psychogenic polydipsia[17][18]

PTSD and phobias

Propranolol is being investigated as a potential treatment for PTSD.[19][20] Propranolol works to inhibit the actions of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that enhances memory consolidation. Individuals given propranolol immediately after trauma experienced fewer stress-related symptoms and lower rates of PTSD than respective control groups who did not receive the drug.[21] Due to the fact that memories and their emotional content are reconsolidated in the hours after they are recalled/re-experienced, propranolol can also diminish the emotional impact of already formed memories; for this reason, it is also being studied in the treatment of specific phobias, such as arachnophobia, dental fear, and social phobia.[22]

Ethical and legal questions have been raised surrounding the use of propranolol-based medications for use as a "memory damper", including: altering memory-recalled evidence during an investigation, modifying behavioral response to past (albeit traumatic) experiences, the regulation of these drugs, and others.[23] However, Hall and Carter have argued that many such objections are "based on wildly exaggerated and unrealistic scenarios that ignore the limited action of propranolol in affecting memory, underplay the debilitating impact that PTSD has on those who suffer from it, and fail to acknowledge the extent to which drugs like alcohol are already used for this purpose."[24]

Others

- Essential tremor. Evidence for use for akathisia however is insufficient[25]

- Migraine and cluster headache prevention[26][27] and in primary exertional headache[28]

- Hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating)

- Proliferating infantile hemangioma

- Glaucoma

- Thyrotoxicosis by deiodinase inhibition

Propranolol may be used to treat severe infantile hemangiomas (IHs). This treatment shows promise as being superior to corticosteroids when treating IHs. Extensive clinical case evidence and a small controlled trial support its efficacy.[29]

Contraindications

Propranolol should be used with caution in people with:[30]

- Diabetes mellitus or hyperthyroidism, since signs and symptoms of hypoglycaemia may be masked

- Peripheral vascular disease and Raynaud's syndrome, which may be exacerbated

- Phaeochromocytoma, as hypertension may be aggravated without prior alpha blocker therapy

- Myasthenia gravis, which may be worsened

- Other drugs with bradycardic effects

Propranolol is contraindicated in patients with:[30]

- Reversible airways diseases, particularly asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Bradycardia (<60 beats/minute)

- Sick sinus syndrome

- Atrioventricular block (second- or third-degree)

- Shock

- Severe hypotension

- Cocaine toxicity [per American Heart Association guidelines, 2005]

Pregnancy and lactation

Propranolol, like other beta blockers, is classified as pregnancy category C in the United States and ADEC category C in Australia. β-blocking agents in general reduce perfusion of the placenta which may lead to adverse outcomes for the neonate, including pulmonary or cardiac complications, or premature birth. The newborn may experience additional adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and bradycardia.[31]

Most β-blocking agents appear in the milk of lactating women. However, propranolol is highly bound to proteins in the bloodstream and is distributed into breast milk at very low levels.[32] These low levels are not expected to pose any risk to the breastfeeding infant, and the American Academy of Pediatrics considers propranolol therapy "generally compatible with breastfeeding".[31][32][33][34]

Adverse effects

Due to the high penetration across the blood–brain barrier, lipophilic beta blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol are more likely than other less lipophilic beta blockers to cause sleep disturbances such as insomnia and vivid dreams, and nightmares.[35] Dreaming (rapid eye movement sleep, REM) was reduced and increased awakening.[36]

Adverse drug reactions associated with propranolol therapy are similar to other lipophilic beta blockers.

Overdose

In overdose propranolol is associated with seizures.[37] Cardiac arrest may occur in propranolol overdose due to sudden ventricular arrhythmias, or cardiogenic shock which may ultimately culminate in bradycardic PEA.[38] Therefore, propranolol should be used with extreme caution in depressed or atypically depressed patients with possible suicidal ideation.

Interactions

Since beta blockers are known to relax the cardiac muscle and to constrict the smooth muscle, beta-adrenergic antagonists, including propranolol, have an additive effect with other drugs which decrease blood pressure, or which decrease cardiac contractility or conductivity. Clinically significant interactions particularly occur with:[30]

- Verapamil

- Epinephrine (adrenalin)

- β2-adrenergic receptor agonists

- Clonidine

- Ergot alkaloids

- Isoprenaline (isoproterenol)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Quinidine

- Cimetidine

- Lidocaine

- Phenobarbital

- Rifampicin

- Fluvoxamine (slows down the metabolism of propranolol significantly, leading to increased blood levels of propranolol)[39]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 55–272 | Human | [41][42] |

| 5-HT1B | 85 | Rat | [43] |

| 5-HT1D | 4,070 | Pig | [44] |

| 5-HT2A | 4,280 | Human | [45] |

| 5-HT2C | 736–2,457 | Rodent | [46][42] |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | Human | [47] |

| α1 | ND | ND | ND |

| α2 | 1,297–2,789 | Rat | [48] |

| β1 | 0.02–2.69 | Human | [49][50] |

| β2 | 0.01–0.61 | Human | [49][50] |

| β3 | 450 | Mouse | [51] |

| D1 | >10,000 | Human | [42] |

| D2 | >10,000 | Human | [42] |

| H1 | >10,000 | Human | [52] |

| SERT | 3,700 | Rat | [53] |

| NET | 5,000 (IC50) | Rat | [54] |

| DAT | 29,000 (IC50) | Rat | [54] |

| VDCC | >10,000 | Rat | [55] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Propranolol is classified as a non-cardioselective sympatholytic beta blocker that crosses the blood–brain barrier. It is lipid soluble and also has sodium channel blocking effects. Propranolol is a non-selective beta blocker; that is, it blocks the action of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) at both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. It has little intrinsic sympathomimetic activity, but has strong membrane stabilizing activity (only at high blood concentrations, e.g. overdose).[citation needed] Propranolol is able to cross the blood–brain barrier and exert effects in the central nervous system in addition to its peripheral activity.[22]

In addition to blockade of adrenergic receptors, propranolol has very weak inhibitory effects on the norepinephrine transporter and/or weakly stimulates norepinephrine release (i.e., the concentration of norepinephrine is increased in the synapse).[56][54] Since propranolol blocks β-adrenoceptors, the increase in synaptic norepinephrine only results in α-adrenoceptor activation, with the α1-adrenoceptor being particularly important for effects observed in animal models.[56][54] Therefore, it can be looked upon as a weak indirect α1-adrenoceptor agonist in addition to potent β-adrenoceptor antagonist.[56][54] In addition to its effects on the adrenergic system, there is evidence that indicates that propranolol may act as a weak antagonist of certain serotonin receptors, namely the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors.[57][58]

Both enantiomers of propranolol have a local anesthetic (topical) effect, which is normally mediated by blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels. Studies have demonstrated propranolol's ability to block cardiac, neuronal, and skeletal voltage-gated sodium channels, accounting for its known membrane stabilizing effect and antiarrhythmic and other central nervous system effects.[59][60][61]

Pharmacokinetics

Propranolol is rapidly and completely absorbed, with peak plasma levels achieved about 1–3 hours after ingestion. Coadministration with food appears to enhance bioavailability.[62] Despite complete absorption, propranolol has a variable bioavailability due to extensive first-pass metabolism. Hepatic impairment therefore increases its bioavailability. The main metabolite 4-hydroxypropranolol, with a longer half-life (5.2–7.5 hours) than the parent compound (3–4 hours), is also pharmacologically active.

Propranolol is a highly lipophilic drug achieving high concentrations in the brain. The duration of action of a single oral dose is longer than the half-life and may be up to 12 hours, if the single dose is high enough (e.g., 80 mg). Effective plasma concentrations are between 10 and 100 mg/l.[citation needed] Toxic levels are associated with plasma concentrations above 2000 mg/l.[citation needed]

History

British scientist James W. Black developed propranolol in the 1960s.[63] In 1988, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery. Propranolol was inspired by the early β-adrenergic antagonists dichloroisoprenaline and pronethalol. The key difference, which was carried through to essentially all subsequent beta blockers, was the inclusion of an oxymethylene group (-O-CH2-) between the aryl and ethanolamine moieties of pronethalol, greatly increasing the potency of the compound. This also apparently eliminated the carcinogenicity found with pronethalol in animal models.

Newer, more cardio-selective beta blockers (such as bisoprolol, nebivolol, carvedilol, or metoprolol) are now used in the treatment of hypertension.

Society and culture

In a 1987 study by the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians, 27% of interviewed members admitted to using beta blockers such as propranolol for musical performances.[64] For about 10–16% of performers, their degree of stage fright is considered pathological.[64][65] Propranolol is used by musicians, actors, and public speakers for its ability to treat anxiety symptoms activated by the sympathetic nervous system.[66]

Brand names

Original propranolol was marketed in 1965 under the brand name Inderal and manufactured by ICI Pharmaceuticals (now AstraZeneca). Propranolol is also marketed under brand names Avlocardyl, Deralin, Dociton, Inderalici, InnoPran XL, Sumial, Anaprilin, and Bedranol SR (Sandoz). In India it is marketed under brand names such as Ciplar and Ciplar LA by Cipla. Hemangeol, a 4.28 mg/mL solution of propranolol, is indicated for the treatment of proliferating infantile hemangioma.[67]

Research

Clinical research has been conducted to learn if propranolol could be useful in the treatment of some cancers.[68]

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Propranolol hydrochloride". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Davidson, JR (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder: what does the evidence tell us?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 12: 20–6. PMID 17092192.

- ^ Chinnadurai, S; Fonnesbeck, C; Snyder, KM; Sathe, NA; Morad, A; Likis, FE; McPheeters, ML (February 2016). "Pharmacologic Interventions for Infantile Hemangioma: A Meta-analysis". Pediatrics. 137 (2): e20153896. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3896. PMID 26772662.

- ^ Bryson, Peter D. (1997). Comprehensive review in toxicology for emergency clinicians (3 ed.). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. p. 167. ISBN 9781560326120. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gerald G. Briggs, Roger K. Freeman, Sumner J. Yaffe (2011). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation : a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1226. ISBN 9781608317080. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Russell, RM (January 2004). "The enigma of beta-carotene in carcinogenesis: what can be learned from animal studies". The Journal of Nutrition. 134 (1): 262S–268S. PMID 14704331.

- ^ Ravina, Enrique (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 331. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Propranolol". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sheetal Ladva (28 June 2006). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Paul A. James, MD; et al. (5 February 2014). "2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults". The Journal of the American Medical Association. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Steenen, SA; van Wijk, AJ; van der Heijden, GJ; van Westrhenen, R; de Lange, J; de Jongh, A (February 2016). "Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 30 (2): 128–39. doi:10.1177/0269881115612236. PMC 4724794. PMID 26487439.

- ^ Kornischka J, Cordes J, Agelink MW (April 2007). "[40 years beta-adrenoceptor blockers in psychiatry]". Fortschritte der Neurologie · Psychiatrie (in German). 75 (4): 199–210. doi:10.1055/s-2006-944295. PMID 17200914.

- ^ Thibaut F, Colonna L (1993). "[Anti-aggressive effect of beta-blockers]". L'Encéphale (in French). 19 (3): 263–7. PMID 7903928.

- ^ Vieweg V, Pandurangi A, Levenson J, Silverman J (1994). "The consulting psychiatrist and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in schizophrenia". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 24 (4): 275–303. doi:10.2190/5WG5-VV1V-BXAD-805K. PMID 7737786.

- ^ Kishi Y, Kurosawa H, Endo S (1998). "Is propranolol effective in primary polydipsia?". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 28 (3): 315–25. doi:10.2190/QPWL-14H7-HPGG-A29D. PMID 9844835.

- ^ "Doctors test a drug to ease traumatic memories - Mental Health - MSNBC.com". Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brunet A, Orr SP, Tremblay J, Robertson K, Nader K, Pitman RK (May 2008). "Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 42 (6): 503–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.006. PMID 17588604.

- ^ Vaiva, G.; Ducrocq, F.; Jezekiel, K.; Averland, B.; Lestavel, P.; Brunet, A.; Marmar, C.R. (2003). "Immediate treatment with propranolol decreases post-traumatic stress disorder two months after trauma". Biological Psychiatry. 54: 947–949. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00412-8.

- ^ a b Steenen, S. A.; van Wijk, A. J.; van der Heijden, G. J.; van Westrhenen, R.; de Lange, J.; de Jongh, A. (2015). "Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 30 (2): 128–139. doi:10.1177/0269881115612236. ISSN 0269-8811. PMC 4724794. PMID 26487439.

- ^ Kolber, Adam J. (2006). "Therapeutic Forgetting: The Legal and Ethical Implications of Memory Dampening". Vanderbilt Law Review, San Diego Legal Studies Paper No. 07-37. 59: 1561.

- ^ Hall, Wayne; Carter, Adrian (2007). "Debunking Alarmist Objections to the Pharmacological Prevention of PTSD". American Journal of Bioethics. 7 (9): 23–25. doi:10.1080/15265160701551244.

- ^ Lima, AR; Bacalcthuk, J; Barnes, TR; Soares-Weiser, K (18 October 2004). "Central action beta-blockers versus placebo for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4): CD001946. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001946.pub2. PMID 15495022.

- ^ Shields, Kevin G.; Peter J. Goadsby (January 2005). "Propranolol modulates trigeminovascular responses in thalamic ventroposteromedial nucleus: a role in migraine?". Brain. 128 (1): 86–97. doi:10.1093/brain/awh298. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Eadie, M.; J. H. Tyrer (1985). The Biochemistry of Migraine. New York: Springer. p. 148. ISBN 9780852007310. OCLC 11726870. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clinical summary Archived 24 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hogeling, M. (2012). "Propranolol for Infantile Hemangiomas: A Review". Current Dermatology Reports. 1: Online-first. doi:10.1007/s13671-012-0026-6.

- ^ a b c Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ a b Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Cardiovascular Drugs". Martindale: The complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 1226–1381. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b [No authors listed] (2007). "Propranolol". In: Drugs and Lactation Database. U.S. National Library of Medicine Toxicology Data Network. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ [No authors listed] (September 2001). "Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk". Pediatrics. 108 (3): 776–89. PMID 11533352.

- ^ Spencer JP, Gonzalez LS, Barnhart DJ (July 2001). "Medications in the breast-feeding mother". Am Fam Physician. 64 (1): 119–26. PMID 11456429.

- ^ Cruickshank JM (2010). "Beta-blockers and heart failure". Indian Heart J. 62 (2): 101–10. PMID 21180298.

- ^ Betts TA, Alford C (1985). "Beta-blockers and sleep: a controlled trial". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 28: 65–8. doi:10.1007/bf00543712. PMID 2865152.

- ^ Reith, DM; Dawson, AH; Epid, D; Whyte, IM; Buckley, NA; Sayer, GP (1996). "Relative toxicity of beta blockers in overdose". Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 34 (3): 273–8. doi:10.3109/15563659609013789. PMID 8667464.

- ^ Holstege, CP; Eldridge, DL; Rowden, AK (February 2006). "ECG manifestations: the poisoned patient". Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 24 (1): 159–77, vii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2005.08.012. PMID 16308118.

- ^ van Harten J (1995). "Overview of the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 29 (Suppl 1): 1–9. doi:10.2165/00003088-199500291-00003. PMID 8846617.

- ^ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database" (HTML). Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Hamon M, Lanfumey L, el Mestikawy S, Boni C, Miquel MC, Bolaños F, Schechter L, Gozlan H (1990). "The main features of central 5-HT1 receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 3 (5–6): 349–60. PMID 2078271.

- ^ a b c d Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, Schwartz RW, Haggart D, O'Brien A, White A, Kennedy JM, Craymer K, Farrington L, Auh JS (1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Res. Monogr. 178: 440–66. PMID 9686407.

- ^ Engel G, Göthert M, Hoyer D, Schlicker E, Hillenbrand K (1986). "Identity of inhibitory presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) autoreceptors in the rat brain cortex with 5-HT1B binding sites". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 332 (1): 1–7. PMID 2936965.

- ^ Schlicker E, Fink K, Göthert M, Hoyer D, Molderings G, Roschke I, Schoeffter P (1989). "The pharmacological properties of the presynaptic serotonin autoreceptor in the pig brain cortex conform to the 5-HT1D receptor subtype". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 340 (1): 45–51. PMID 2797214.

- ^ Elliott JM, Kent A (1989). "Comparison of [125I]iodolysergic acid diethylamide binding in human frontal cortex and platelet tissue". J. Neurochem. 53 (1): 191–6. PMID 2723656.

- ^ Yagaloff KA, Hartig PR (1985). "125I-lysergic acid diethylamide binds to a novel serotonergic site on rat choroid plexus epithelial cells". J. Neurosci. 5 (12): 3178–83. PMID 4078623.

- ^ Barnes JM, Barnes NM, Costall B, Ironside JW, Naylor RJ (1989). "Identification and characterisation of 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 recognition sites in human brain tissue". J. Neurochem. 53 (6): 1787–93. PMID 2809591.

- ^ Boyajian CL, Leslie FM (1987). "Pharmacological evidence for alpha-2 adrenoceptor heterogeneity: differential binding properties of [3H]rauwolscine and [3H]idazoxan in rat brain". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 241 (3): 1092–8. PMID 2885406.

- ^ a b Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, Luyten WH, Van Gompel P, Lesage AS, De Loore K, Leysen JE (1996). "Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 124 (1–2): 57–73. PMID 8935801.

- ^ a b Fraundorfer PF, Fertel RH, Miller DD, Feller DR (1994). "Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of high-affinity trimetoquinol analogs on guinea pig and human beta adrenergic receptor subtypes: evidence for partial agonism". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 270 (2): 665–74. PMID 7915318.

- ^ Nahmias C, Blin N, Elalouf JM, Mattei MG, Strosberg AD, Emorine LJ (1991). "Molecular characterization of the mouse beta 3-adrenergic receptor: relationship with the atypical receptor of adipocytes". EMBO J. 10 (12): 3721–7. PMC 453106. PMID 1718744.

- ^ Kanba S, Richelson E (1984). "Histamine H1 receptors in human brain labelled with [3H]doxepin". Brain Res. 304 (1): 1–7. PMID 6146381.

- ^ Kovachich GB, Aronson CE, Brunswick DJ, Frazer A (1988). "Quantitative autoradiography of serotonin uptake sites in rat brain using [3H]cyanoimipramine". Brain Res. 454 (1–2): 78–88. PMID 2970277.

- ^ a b c d e Tuross N, Patrick RL (1986). "Effects of propranolol on catecholamine synthesis and uptake in the central nervous system of the rat". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 237 (3): 739–45. PMID 2872325.

- ^ Zobrist RH, Mecca TE (1990). "[3H]TA-3090, a selective benzothiazepine-type calcium channel receptor antagonist: in vitro characterization". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 253 (2): 461–5. PMID 2338642.

- ^ a b c Young, Richard; Glennon, Richard A. (2008). "S(−)Propranolol as a discriminative stimulus and its comparison to the stimulus effects of cocaine in rats". Psychopharmacology. 203 (2): 369–382. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1317-2. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 18795268.

- ^ Davids E, Lesch KP (1996). "[The 5-HT1A receptor: a new effective principle in psychopharmacologic therapy?]". Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr (in German). 64 (11): 460–72. doi:10.1055/s-2007-996592. PMID 9064274.

- ^ Hoyer D, Clarke DE, Fozard JR, Hartig PR, Martin GR, Mylecharane EJ, Saxena PR, Humphrey PP (1994). "International Union of Pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin)". Pharmacol. Rev. 46 (2): 157–203. PMID 7938165.

- ^ Wang D. W.; Mistry A. M.; Kahlig K. M.; Kearney J. A.; Xiang J.; George A. L. Jr (2010). "Propranolol blocks cardiac and neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels". Front. Pharmacol. 1: 144. doi:10.3389/fphar.2010.00144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bankston J. R.; Kass R. S. (2010). "Molecular determinants of local anesthetic action of beta-blocking drugs: implications for therapeutic management of long QT syndrome variant 3". J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48: 246–253. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.05.012.

- ^ Desaphy J. F.; Pierno S.; De Luca A.; Didonna P.; Camerino D. C. (2003). "Different ability of clenbuterol and salbutamol to block sodium channels predicts their therapeutic use in muscle excitability disorders". Mol. Pharmacol. 63 (3): 659–670. doi:10.1124/mol.63.3.659. PMID 12606775.

- ^ Rang, Humphrey P. (2011). Rang & Dale's pharmacology (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 106. ISBN 9780702034718.

- ^ Black JW, Crowther AF, Shanks RG, Smith LH, Dornhorst AC (1964). "A new adrenergic betareceptor antagonist". The Lancet. 283 (7342): 1080–1081. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(64)91275-9. PMID 14132613.

- ^ a b Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE, Ottati V, Straus S, Ellis A (1988). "Medical problems among ICSOM musicians: overview of a national survey". Med Probl Perform Artist. 3: 1–8.

- ^ Steptoe A, Malik F, Pay C, Pearson P, Price C, Win Z (1995). "The impact of stage fright on student actors". Br J Psychol. 86: 27–39. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1995.tb02544.x.

- ^ Alan H. Lockwood (1989). "Medical Problems of Musicians". NEJM. 320 (4): 221–227. doi:10.1056/nejm198901263200405.

- ^ "Hemangeol - Food and Drug Administration" (PDF). 1 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pantziarka, P; Bouche, G; Sukhatme, V; Meheus, L; Rooman, I; Sukhatme, VP. "Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO)—Propranolol as an anti-cancer agent". Ecancermedicalscience. 10: 680. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2016.680.

External links

- Stapleton MP (1997). "Sir James Black and propranolol. The role of the basic sciences in the history of cardiovascular pharmacology". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 24 (4): 336–42. PMC 325477. PMID 9456487.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Propranolol