25I-NBOMe

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 2C-I-NBOMe; 25I; N-Bomb; Smiles; Wizard |

| Routes of administration | Buccal (sublabial), sublingual, insufflated, inhalation, intravenous, intramuscular, rectal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver |

| Elimination half-life | Unknown |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

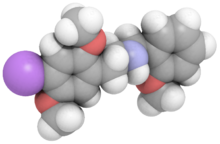

| Formula | C18H22INO3 |

| Molar mass | 427.282 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

|

25I-NBOMe (2C-I-NBOMe, Cimbi-5, and also shortened to "25I"), also known as Smiles, or N-Bomb, is a novel synthetic psychoactive substance with strong hallucinogenic properties, synthesized in 2003 for research purposes. Since 2010, it has circulated in the recreational drug scene, often misrepresented as LSD.

25I was synthesized for biochemistry research to map the brain's usage of the type 2A serotonin receptor. A derivative of the substituted phenethylamine 2C-I family, it is the most well-known member of the 25-NB family. It was discovered in 2003 by chemist Ralf Heim at the Free University of Berlin, who published his findings in his PhD dissertation.[5] The compound was subsequently investigated by a team at Purdue University led by David Nichols.[6]

The carbon-11 labelled version of 25I-NBOMe, [11C]Cimbi-5, was synthesized and validated as a radiotracer for positron emission tomography (PET) in Copenhagen.[7][8] Being the first 5-HT2A receptor full agonist PET radioligand, [11C]CIMBI-5 shows promise as a more functional marker of these receptors, particularly in their high affinity states.[7]

Street and media nicknames for this drug are: "N-Bomb", "Solaris", "Smiles", and "Wizard", although the drug is frequently fraudulently sold as LSD.[9][10][11]

Due to its physical effects and risk of overdose, there have been multiple deaths attributed to the drug. Its long term toxicity is unknown due to lack of existing research.

Recreational use

[edit]Although 25I-NBOMe was discovered in 2003, it did not emerge as a common recreational drug until 2010, when it was first sold by vendors specializing in the supply of designer drugs.[12] In a slang context, the name of the compound is often shortened to "25I" or is simply called "N-Bomb".[13] According to a 2014 survey, 25I-NBOMe was the most frequently used of the NBOMe series.[14] By 2013, case reports of 25I-NBOMe intoxication, with and without analytic confirmation of the drug in the body, were becoming increasingly common in the medical literature.[15]

25I-NBOMe is widely rumored to be orally inactive; however, apparent overdoses have occurred via oral administration. Common routes of administration include sublingual, buccal, and intranasal.[14] For sublingual and buccal administration, 25I-NBOMe is often applied to sheets of blotter paper of which small portions (tabs) are held in the mouth to allow absorption through the oral mucosa.[16][17] There are reports of intravenous injection of 25I-NBOMe solution and smoking the drug in powdered form.[18][19]

Due to its potency and much lower cost than so-called classical or traditional psychedelics, 25I-NBOMe blotters are frequently misrepresented as, or mistaken for LSD blotters.[20] Even small quantities of 25I-NBOMe can produce a large number of blotters. Vendors would import 25I-NBOMe in bulk (e.g., 1 kg containers) and resell individual doses for a considerable profit.[17]

Dosage

[edit]25I-NBOMe is potent, being active in sub-milligram doses. A common dose of the hydrochloride salt is 600–1,200 μg. The UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs states that a common dose is between 50 and 100 μg,[17] although other sources indicate that these figures are incorrect; Erowid tentatively suggests that the threshold dosage for humans is 50–250 μg, with a light dose between 200–600 μg, a common dose at 500–800 μg, and a strong dose at 700–1500 μg.[21]

At this level of potency, it is not possible to accurately measure a single dose of 25I-NBOMe powder without an analytical balance, and attempting to do so may put the user at significant risk of overdose.[17] There is a high risk of overdose due to the small margin between a high-dose and an over-dose, which is not a risk with the similar drug LSD. One study has shown that 25I-NBOMe blotters have 'hotspots' of the drug and the dosage is not evenly applied over the surface of the paper, which could lead to overdose.[22]

Effects

[edit]25I-NBOMe effects usually last 6–10 hours if taken sublingually, or buccally (between gum and cheek).[19][medical citation needed] When it is insufflated (snorted), effects usually last 4–6 hours.[19][medical citation needed]

25I-NBOMe has similar effects to LSD, though users report more negative effects while under the influence and more risk of harm following use as compared to the classical psychedelics.[14]

Case reports of seven British males who presented to an emergency room following analytically confirmed 25I-NBOMe intoxication suggest the following potential adverse effects: "tachycardia (n = 7), hypertension (4), agitation (6), aggression, visual and auditory hallucinations (6), seizures (3), hyperpyrexia (3), clonus (2), elevated white blood cell count (2), elevated creatine kinase (7), metabolic acidosis (3), and acute kidney injury (1)."[18]

25I-NBOMe can be consumed in liquid, powder or paper form and can be snorted, injected, mixed with food, or smoked, but sublingual administration is most common.[23]

Toxicity and harm potential

[edit]NBOMe compounds are often associated with life-threatening toxicity and death.[24][25] Studies on NBOMe family of compounds demonstrated that the substance exhibit neurotoxic and cardiotoxic activity.[26] Reports of autonomic dysfunction remains prevalent with NBOMe compounds, with most individuals experiencing sympathomimetic toxicity such as vasoconstriction, hypertension and tachycardia in addition to hallucinations.[27][28][29][30][31] Other symptoms of toxidrome include agitation or aggression, seizure, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, hypertonia, rhabdomyolysis, and death.[27][31][25] Researchers report that NBOMe intoxication frequently display signs of serotonin syndrome.[32] The likelihood of seizure is higher in NBOMes compared to other psychedelics.[26]

NBOMe and NBOHs are regularly sold as LSD in blotter papers,[25][33] which have a bitter taste and different safety profiles.[27][24] Despite high potency, recreational doses of LSD have only produced low incidents of acute toxicity.[24] Fatalities involved in NBOMe intoxication suggest that a significant number of individuals ingested the substance which they believed was LSD,[29] and researchers report that "users familiar with LSD may have a false sense of security when ingesting NBOMe inadvertently".[27] While most fatalities are due to the physical effects of the drug, there have also been reports of death due to self-harm and suicide under the influence of the substance.[34][35][27]

Given limited documentation of NBOMe consumption, the long-term effects of the substance remain unknown.[27] NBOMe compounds are not active orally,[a] and are usually taken sublingually.[37]: 3 When NBOMes are administered sublingually, numbness of the tongue and mouth followed by a metallic chemical taste was observed, and researchers describe this physical side effect as one of the main discriminants between NBOMe compounds and LSD.[38][39][40]Neurotoxic and cardiotoxic actions

[edit]Many of the NBOMe compounds have high potency agonist activity at additional 5-HT receptors and prolonged activation of 5-HT2B can cause cardiac valvulopathy in high doses and chronic use.[25][30] 5-HT2B receptors have been strongly implicated in causing drug-induced valvular heart disease.[41][42][43] The high affinity of NBOMe compounds for adrenergic α1 receptor has been reported to contribute to the stimulant-type cardiovascular effects.[30]

In vitro studies, 25C-NBOMe has been shown to exhibit cytotoxicity on neuronal cell lines SH-SY5Y, PC12, and SN471, and the compound was more potent than methamphetamine at reducing the visibility of the respective cells; the neurotoxicity of the compound involves activation of MAPK/ERK cascade and inhibition of Akt/PKB signaling pathway.[26] 25C-NBOMe, including the other derivative 25D-NBOMe, reduced the visibility of cardiomyocytes H9c2 cells, and both substances downregulated expression level of p21 (CDC24/RAC)-activated kinase 1 (PAK1), an enzyme with documented cardiac protective effects.[26]

Preliminary studies on 25C-NBOMe have shown that the substance is toxic to development, heart health, and brain health in zebrafish, rats, and Artemia salina, a common organism for studying potential drug effects on humans, but more research is needed on the topic, the dosages, and if the toxicology results apply to humans. Researchers of the study also recommended further investigation of the drug's potential in damaging pregnant women and their fetus due to the substance's damaging effects to development.[44][45]Emergency treatment

[edit]Attributed deaths

[edit]Reports of deaths and significant injuries have been attributed to the use of 25I-NBOMe, prompting some governments to control its possession, production, and sale. The website Erowid states that 25I-NBOMe is extremely potent and should not be snorted, and that the drug "appears to have led to several deaths in the past year."[20] Several non-fatal overdoses requiring prolonged hospitalization have also been reported.[17][15][18]

As of August 2015, 25I-NBOMe has reportedly led to at least 19 overdose deaths in the United States.[13][46] In June 2012, two teens in Grand Forks, North Dakota and East Grand Forks, Minnesota fatally overdosed on a substance that was allegedly 25I-NBOMe, resulting in lengthy sentences for two of the parties involved and a Federal indictment against the Texas-based online vendor.[47] A 21-year-old man from Little Rock, Arkansas died in October 2012 after taking a liquid drop of the drug nasally at a music festival. He was reported to have consumed caffeinated alcoholic beverages for "several hours" beforehand. It is unclear what other drugs he may have consumed, as autopsies generally do not test for the presence of research chemicals.[48] In January 2013, an 18-year-old in Scottsdale, Arizona, died after consuming 25I-NBOMe sold as LSD; a toxicology screening found no other drugs in the person's system. The drug is the suspected cause of death in another Scottsdale, Arizona, incident in April 2013.[17] It is also cited in the death of a 21-year-old woman in August 2013[49] and the death of a 17-year-old in Minnesota in January 2014,[50] as well as the death of a 15-year old in Washington in September 2014.[51] In October 2015, a 20-year-old UCSB student from Isla Vista, California died of "acute hallucinogenic polysubstance intoxication" with an additional significant cause of death being "sharp force trauma of the upper extremity", according to a statement from Santa Barbara County Sheriff's office; the autopsy determined Sanchez was under the influence of two hallucinogenic drugs at the time of his death: ketamine and 25I-NBOMe. The noted sharp force trauma refers to a deep cut on Sanchez's right forearm, which was caused when he punched and broke a large residential window while suffering hallucinations.[52]

25I-NBOMe has been implicated in multiple deaths in Australia. In March 2012, a man in Australia died from injuries sustained by running into trees and power poles while intoxicated by 25I-NBOMe.[53] A Sydney teenager jumped off a balcony to his death on June 5, 2013, while on 25I-NBOMe.[54]

25I-NBOMe has been linked to a major case on January 20, 2016, in Cork, Republic of Ireland, which left six teenagers hospitalized, one of whom later died. At least one of the teenagers suffered a cardiac arrest, according to reports, along with extreme internal bleeding.[55]

At least one suicide, and two attempted suicides leading to hospitalisation, have occurred while under the effects of 25I-NBOMe.[56]

Pharmacology

[edit]| Receptor | Kd (nM) | ± |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2A | 0.044 | |

| 5-HT2B | 231 | 73 |

| 5-HT2C | 2 | |

| 5-HT6 | 73 | 12 |

| μ-opioid | 82 | 14 |

| κ-opioid | 288 | 50 |

| H1 | 189 | 35 |

25I-NBOMe acts as a highly potent full agonist for the human 5-HT2A receptor,[57][59] with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.044 nM, making it some sixteen times the potency of 2C-I itself at this receptor. A radiolabelled form of 25I-NBOMe can be used for mapping the distribution of 5-HT2A receptors in the brain.[58]

25I-NBOMe induces a head-twitch response in mice which is blocked completely by a selective 5-HT2A antagonist, suggesting its psychedelic effects are mediated by 5-HT2A. This study suggested that 25I-NBOMe is approximately 14-fold more potent than 2C-I in-vivo.[60]

While in-vitro studies showed that N-benzyl derivatives of 2C-I were significantly increased in potency compared to 2C-I, the N-benzyl derivatives of the related compound DOI were inactive.[61]

25I-NBOMe also has weaker interactions with multiple other receptors. Kd values for interaction with the following targets were greater than 500 nM: 5-HT1A, D3, H2, 5-HT1D, α1A adrenergic, δ opioid, serotonin uptake transporter, 5-HT5A, 5-HT1B, D2, 5-HT7, D1, 5-HT3, 5-HT1E, D5, muscarinic M1-M5, H3, and the dopamine uptake transporter.[58]

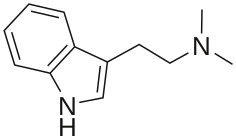

Chemistry

[edit]Like other 2C-X-NBOMe molecules, 25I-NBOMe is a derivative of the 2C family of phenethylamines described by chemist Alexander Shulgin in his book PiHKAL.[17][15] Specifically, 25I-NBOMe is an N-benzyl derivative of the phenethylamine molecule 2C-I, formed by adding a 2-methoxybenzyl (BnOMe) onto the nitrogen (N) of the phenethylamine backbone. This substitution significantly increases the potency of the molecule.[17]

Analogues

[edit]Analogues and derivatives of 2C-I:

25I-NB*:

- 25I-NBF

- 25I-NBMD

- 25I-NB34MD

- 25I-NBOH

- 25I-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CI)

- 25I-NB3OMe

- 25I-NB4OMe

Synthesis

[edit]25I-NBOMe is usually synthesised from 2C-I and 2-methoxybenzaldehyde, via reductive alkylation. It can be done stepwise by first making the imine and then reducing the formed imine with sodium borohydride, or by direct reaction with sodium triacetoxyborohydride.[5]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]Australia

[edit]25I-NBOMe was explicitly scheduled in Queensland drug law in April 2012, and in New South Wales in October 2013, as were some related compounds such as 25B-NBOMe. The Australian federal government has no specific legislation concerning any of the N-benzyl phenethylamines.[63]

Canada

[edit]As of October 31, 2016; 25I-NBOMe is a controlled substance (Schedule III) in Canada.[64]

China

[edit]As of October 2015 25I-NBOMe is a controlled substance in China.[65]

European Union

[edit]In September 2014 the European Union implemented a ban of 25I-NBOMe in all its member states.[66]

Finland

[edit]25I-NBOMe is scheduled in government decree on narcotic substances, preparations and plants as of 2022 and is hence illegal to possess or use.[67]

Israel

[edit]Israel banned 25I-NBOMe in 2013.[68]

Russia

[edit]Russia was the first country to pass specific regulations on the NBOMe series. All drugs in the NBOMe series, including 25I-NBOMe, became illegal in Russia in October 2011.[68]

United Kingdom

[edit]This substance is a Class A drug in the United Kingdom as a result of the N-benzylphenethylamine catch-all clause in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[69]

United States

[edit]On Nov 15, 2013, the DEA added 25I-NBOMe (and 25C-, and 25B-NBOMe) to Schedule I using their emergency scheduling powers, making those NBOMe compounds "temporarily" in Schedule I for 2 years.[46] In November 2015, the temporary scheduling was extended for an additional year[70] while permanent scheduling was arranged.[71] 25I-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe and 25C-NBOMe are currently Schedule 1 Substances according to 21 CFR 1308.11(d).[72]

Romania

[edit]In 2011, Romania banned all psychoactive substances.[73]

Serbia

[edit]25I-NBOMe was put on the list of prohibited substances in March 2015.[74]

Sweden

[edit]The Riksdag added 25I-NBOMe to Narcotic Drugs Punishments Act under Swedish schedule I ("substances, plant materials and fungi which normally do not have medical use") as of August 1, 2013, published by Medical Products Agency (MPA) in regulation LVFS 2013:15 listed as 25I-NBOMe, and 2-(4-jodo-2,5-dimetoxifenyl)-N-(2-metoxibensyl)etanamin.[75]

Taiwan

[edit]Following the European rule from 2014, 25I-NBOMe was put in class 4 of prohibited substances.[76]

Brazil

[edit]All drugs in the NBOMe family, including 25I-NBOMe, are illegal.

United Arab Emirates

The UAE has a zero-tolerance policy for recreational use of drugs. Federal Law No. 14 of 1995 criminalises production, import, export, transport, buying, selling, possessing, storing of narcotic and psychotropic substances (Including 25i-NBOMe) unless done so as part of supervised and regulated medical or scientific activities in accordance with the applicable laws. The UAE police has dedicated departments to deal with drugs' issues.[77]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The potency of N-benzylphenethylamines via buccal, sublingual, or nasal absorption is 50-100 greater (by weight) than oral route compared to the parent 2C-x compounds.[36] Researchers hypothesize the low oral metabolic stability of N-benzylphenethylamines is likely causing the low bioavailability on the oral route, although the metabolic profile of this compounds remains unpredictable; therefore researchers state that the fatalities linked to these substances may partly be explained by differences in the metabolism between individuals.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Part J — 2C-phenethylamines)". Canada Gazette. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ UK Home Office (2014). "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Ketamine etc.) (Amendment) Order 2014". UK Government. Archived from the original on 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ "Substance Details 25I-NBOMe". Archived from the original on 2024-01-23. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ a b Heim R (25 March 2003). "Synthese und Pharmakologie potenter 5-HT2A-Rezeptoragonisten mit N-2-Methoxybenzyl-Partialstruktur. Entwicklung eines neuen Struktur-Wirkungskonzepts" (in German). diss.fu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- ^ Braden MR (2007). "Towards a biophysical understanding of hallucinogen action". Dissertation. Purdue University: 1–176. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

- ^ a b Ettrup A, Palner M, Gillings N, Santini MA, Hansen M, Kornum BR, et al. (November 2010). "Radiosynthesis and evaluation of 11C-CIMBI-5 as a 5-HT2A receptor agonist radioligand for PET". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 51 (11): 1763–1770. doi:10.2967/jnumed.109.074021. PMID 20956470.

- ^ Hansen M (16 December 2010). "Design and synthesis of selective serotonin receptor agonists for positron emission tomography imaging of the brain". Ph.D. Thesis. Det Farmaceutiske Fakultet, København. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.4529.

- ^ "Erowid 25I-NBOMe Vault". Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ Vanderbilt University Medical Center (9 April 2015). "Poison center warns against designer drug 'N-bomb'". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Mackin, Teresa (October 9, 2012). Dangerous synthetic drug making its way across the country. Archived October 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine WISH-TV

- ^ Morgans J (2017-02-08). "Everything We Know About NBOMe and Why it's Killing People". Vice. Archived from the original on 2019-07-24. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ a b Hastings D (May 6, 2013). "New drug N-bomb hits the street, terrifying parents, troubling cops". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Lawn W, Barratt M, Williams M, Horne A, Winstock A (August 2014). "The NBOMe hallucinogenic drug series: Patterns of use, characteristics of users and self-reported effects in a large international sample". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (8): 780–788. doi:10.1177/0269881114523866. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_73366. PMID 24569095. S2CID 35219099.

- ^ a b c Rose SR, Poklis JL, Poklis A (March 2013). "A case of 25I-NBOMe (25-I) intoxication: a new potent 5-HT2A agonist designer drug". Clinical Toxicology. 51 (3): 174–177. doi:10.3109/15563650.2013.772191. PMC 4002208. PMID 23473462.

- ^ Poklis JL, Raso SA, Alford KN, Poklis A, Peace MR (October 2015). "Analysis of 25I-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe and Other Dimethoxyphenyl-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl) Methyl]Ethanamine Derivatives on Blotter Paper". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (8): 617–623. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv073. PMC 4570937. PMID 26378135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Iversen L (4 June 2013). "Temporary class drug order on benzofury and NBOMe compounds". Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Gov.Uk. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Hill SL, Doris T, Gurung S, Katebe S, Lomas A, Dunn M, et al. (July 2013). "Severe clinical toxicity associated with analytically confirmed recreational use of 25I-NBOMe: case series". Clinical Toxicology. 51 (6): 487–492. doi:10.3109/15563650.2013.802795. PMID 23731373. S2CID 41259282.

- ^ a b c "2C-I-NBOMe (25I) Effects". Erowid. Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ a b "25I-NBOMe". Erowid.

- ^ "2C-I-NBOMe (25I) Dose". Erowid. Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ Lützen E, Holtkamp M, Stamme I, Schmid R, Sperling M, Pütz M, Karst U (April 2020). "Multimodal imaging of hallucinogens 25C- and 25I-NBOMe on blotter papers". Drug Testing and Analysis. 12 (4): 465–471. doi:10.1002/dta.2751. PMID 31846172. S2CID 209388281.

- ^ Areas-Holmblad L (2016-12-11). "Using 'n-bomb' can kill you ~ Drug Addiction Now". Addiction Now | Substance Abuse, Drug Addiction and Recovery News Source. Archived from the original on 2020-09-13. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ a b c Sean I, Joe R, Jennifer S, and Shaun G (28 March 2022). "A cluster of 25B-NBOH poisonings following exposure to powder sold as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)". Clinical Toxicology. 60 (8): 966–969. doi:10.1080/15563650.2022.2053150. PMID 35343858. S2CID 247764056.

- ^ a b c d Amy E, Katherine W, John R, Sonyoung K, Robert J, Aaron J (December 2018). "Neurochemical pharmacology of psychoactive substituted N-benzylphenethylamines: High potency agonists at 5-HT2A receptors". Biochemical Pharmacology. 158: 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.09.024. PMC 6298744. PMID 30261175.

- ^ a b c d e Jolanta Z, Monika K, and Piotr A (26 February 2020). "NBOMes–Highly Potent and Toxic Alternatives of LSD". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 14: 78. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00078. PMC 7054380. PMID 32174803.

- ^ a b c d e f Lipow M, Kaleem SZ, Espiridion E (30 March 2022). "NBOMe Toxicity and Fatalities: A Review of the Literature". Transformative Medicine. 1 (1): 12–18. doi:10.54299/tmed/msot8578. ISSN 2831-8978. S2CID 247888583.

- ^ Micaela T, Sabrine B, Raffaella A, Giorgia C, Beatrice M, Tatiana B, Federica B, Giovanni S, Francesco B, Fabio G, Krystyna G, Matteo M (21 April 2022). "Effect of -NBOMe Compounds on Sensorimotor, Motor, and Prepulse Inhibition Responses in Mice in Comparison With the 2C Analogs and Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: From Preclinical Evidence to Forensic Implication in Driving Under the Influence of Drugs". Front Psychiatry. 13: 875722. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.875722. PMC 9069068. PMID 35530025.

- ^ a b Cristina M, Matteo M, Nicholas P, Maria C, Micaela T, Raffaella A, Maria L (12 December 2019). "Neurochemical and Behavioral Profiling in Male and Female Rats of the Psychedelic Agent 25I-NBOMe". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 10: 1406. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01406. PMC 6921684. PMID 31915427.

- ^ a b c Anna R, Dino L, Julia R, Daniele B, Marius H, Matthias L (December 2015). "Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs)". Neuropharmacology. 99: 546–553. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.034. ISSN 1873-7064. PMID 26318099. S2CID 10382311.

- ^ a b David W, Roumen S, Andrew C, Paul D (6 February 2015). "Prevalence of use and acute toxicity associated with the use of NBOMe drugs". Clinical Toxicology. 53 (2): 85–92. doi:10.3109/15563650.2015.1004179. PMID 25658166. S2CID 25752763.

- ^ Humston C, Miketic R, Moon K, Ma P, Tobias J (2017-06-05). "Toxic Leukoencephalopathy in a Teenager Caused by the Recreational Ingestion of 25I-NBOMe: A Case Report and Review of Literature". Journal of Medical Cases. 8 (6): 174–179. doi:10.14740/jmc2811w. ISSN 1923-4163.

- ^ Justin P, Stephen R, Kylin A, Alphonse P, Michelle P (2015). "Analysis of 25I-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe and Other Dimethoxyphenyl-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl) Methyl]Ethanamine Derivatives on Blotter Paper". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (8): 617–623. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv073. PMC 4570937. PMID 26378135.

- ^ Morini L, Bernini M, Vezzoli S, Restori M, Moretti M, Crenna S, et al. (October 2017). "Death after 25C-NBOMe and 25H-NBOMe consumption". Forensic Science International. 279: e1–e6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.08.028. PMID 28893436.

- ^ Byard RW, Cox M, Stockham P (November 2016). "Blunt Craniofacial Trauma as a Manifestation of Excited Delirium Caused by New Psychoactive Substances". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 61 (6): 1546–1548. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.13212. PMID 27723094. S2CID 4734566.

- ^ a b Sabastian LP, Christoffer B, Martin H, Martin AC, Jan K, Jesper LK (14 February 2014). "Correlating the Metabolic Stability of Psychedelic 5-HT2A Agonists with Anecdotal Reports of Human Oral Bioavailability". Neurochemical Research. 39 (10): 2018–2023. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1253-y. PMID 24519542. S2CID 254857910.

- ^ Adam H (18 January 2017). "Pharmacology and Toxicology of N-Benzylphenethylamine ("NBOMe") Hallucinogens". Neuropharmacology of New Psychoactive Substances. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 32. Springer. pp. 283–311. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_64. ISBN 978-3-319-52444-3. PMID 28097528.

- ^ Boris D, Cristian C, Marcelo K, Edwar F, Bruce KC (August 2016). "Analysis of 25 C NBOMe in Seized Blotters by HPTLC and GC–MS". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 54 (7): 1153–1158. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmw095. PMC 4941995. PMID 27406128.

- ^ Francesco SB, Ornella C, Gabriella A, Giuseppe V, Rita S, Flaminia BP, Eduardo C, Pierluigi S, Giovanni M, Guiseppe B, Fabrizio S (3 July 2014). "25C-NBOMe: preliminary data on pharmacology, psychoactive effects, and toxicity of a new potent and dangerous hallucinogenic drug". BioMed Research International. 2014: 734749. doi:10.1155/2014/734749. PMC 4106087. PMID 25105138.

- ^ Adam JP, Simon HT, Simon LH (September 2021). "Pharmacology and toxicology of N-Benzyl-phenylethylamines (25X-NBOMe) hallucinogens". Novel Psychoactive Substances: Classification, Pharmacology and Toxicology (2 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 279–300. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818788-3.00008-5. ISBN 978-0-12-818788-3. S2CID 240583877.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Savage JE, Rauser L, McBride A, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL (Dec 2000). "Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications". Circulation. 102 (23): 2836–41. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.23.2836. PMID 11104741.

- ^ Fitzgerald LW, Burn TC, Brown BS, Patterson JP, Corjay MH, Valentine PA, Sun JH, Link JR, Abbaszade I, Hollis JM, Largent BL, Hartig PR, Hollis GF, Meunier PC, Robichaud AJ, Robertson DW (Jan 2000). "Possible role of valvular serotonin 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiopathy associated with fenfluramine". Molecular Pharmacology. 57 (1): 75–81. PMID 10617681.

- ^ Roth BL (Jan 2007). "Drugs and valvular heart disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068265. PMID 17202450.

- ^ Xu P, Qiu Q, Li H, Yan S, Yang M, Naman CB, et al. (26 February 2019). "25C-NBOMe, a Novel Designer Psychedelic, Induces Neurotoxicity 50 Times More Potent Than Methamphetamine In Vitro". Neurotoxicity Research. 35 (4): 993–998. doi:10.1007/s12640-019-0012-x. PMID 30806983. S2CID 255763701.

- ^ Álvarez-Alarcón N, Osorio-Méndez JJ, Ayala-Fajardo A, Garzón-Méndez WF, Garavito-Aguilar ZV (2021). "Zebrafish and Artemia salina in vivo evaluation of the recreational 25C-NBOMe drug demonstrates its high toxicity". Toxicology Reports. 8: 315–323. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.01.010. ISSN 2214-7500. PMC 7868744. PMID 33598409.

- ^ a b "Three More Synthetic Drugs Become Illegal for at Least Two Years". United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Malisow C (13 March 2013). "Breaking Bad: Digital Drug Sales, Analog Drug Deaths". Houston Press. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Martin N (1 November 2012). "21-year-old dies after one drop of new synthetic drug at Voodoo Fest". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Fatal overdose case continues". Hibbing Daily Tribune. 5 March 2015.

- ^ Giles K (28 April 2015). "After friend's OD death, teens get a reprieve". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Lowe LM, Peterson BL, Couper FJ (October 2015). "A Case Review of the First Analytically Confirmed 25I-NBOMe-Related Death in Washington State". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (8): 668–671. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv092. PMID 26378143.

- ^ Nicholas BB (16 November 2015). "Autopsy Results Released in Death of UCSB Student". Daily Nexus. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023.

- ^ "New hallucinogenic drugs lead to Aussie man's death after running repeatedly into trees". TNT Magazine. United Kingdom. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Davies N, Ralston L (2013-06-07). "'He wanted to fly': father says son made a fatal mistake". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2022-06-22. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ Feehan C (21 January 2016). "Powerful N-Bomb drug - responsible for spate of deaths internationally - responsible for hospitalisation of six in Cork". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Lipow M, Kaleem SZ, Espiridion E (2022-03-30). "NBOMe Toxicity and Fatalities: A Review of the Literature". Transformative Medicine. 1 (1): 12–18. doi:10.54299/tmed/msot8578. ISSN 2831-8978. S2CID 247888583. Archived from the original on 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ^ a b Ettrup A, Hansen M, Santini MA, Paine J, Gillings N, Palner M, et al. (April 2011). "Radiosynthesis and in vivo evaluation of a series of substituted 11C-phenethylamines as 5-HT (2A) agonist PET tracers". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 38 (4): 681–693. doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1686-8. PMID 21174090. S2CID 12467684.

- ^ a b c Nichols DE, Frescas SP, Chemel BR, Rehder KS, Zhong D, Lewin AH (June 2008). "High specific activity tritium-labeled N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenethylamine (INBMeO): a high-affinity 5-HT2A receptor-selective agonist radioligand". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (11): 6116–6123. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.050. PMC 2719953. PMID 18468904.

- ^ Silva ME, Heim R, Strasser A, Elz S, Dove S (January 2011). "Theoretical studies on the interaction of partial agonists with the 5-HT2A receptor". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 25 (1): 51–66. Bibcode:2011JCAMD..25...51S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.2670. doi:10.1007/s10822-010-9400-2. PMID 21088982. S2CID 3103050.

- ^ Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA (February 2014). "Effects of the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenethylamine (2C-I) and superpotent N-benzyl derivatives on the head twitch response". Neuropharmacology. 77: 200–207. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.025. PMC 3866097. PMID 24012658.

- ^ Braden MR, Parrish JC, Naylor JC, Nichols DE (December 2006). "Molecular interaction of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor residues Phe339(6.51) and Phe340(6.52) with superpotent N-benzyl phenethylamine agonists". Molecular Pharmacology. 70 (6): 1956–1964. doi:10.1124/mol.106.028720. PMID 17000863. S2CID 15840304.

- ^ "Explore N-(2C-I)-Fentanyl | PiHKAL · info". isomerdesign.com.

- ^ "Poisons Standard October 2015". Australian Government. October 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Part J — 2C-phenethylamines)". Canada Gazette. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Council Implementing Decision (2014/688/EU)". Official Journal of the European Union. 1 October 2014. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2024-05-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "2C-I-NBOMe Legal Status". Erowid. Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Ketamine etc.) (Amendment) Order 2014". UK Statutory Instruments 2014 No. 1106. www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Drug Enforcement Administration (November 2015). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Extension of Temporary Placement of Three Synthetic Phenethylamines in Schedule I. Final order" (PDF). Federal Register. 80 (219): 70657–70659. PMID 26567439. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Three Synthetic Phenethylamines Into Schedule I". Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "eCFR PART 1308—SCHEDULES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES Schedule I." Archived from the original on 2020-09-13. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ "Legea 194/2011 privind combaterea operatiunilor cu produse susceptibile de a avea efecte psihoactive, altele decat cele prevazute de acte normative in vigoare, republicata 2014". Drept OnLine. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ^ "Министарство здравља Републикe Србије". Archived from the original on 2017-12-28. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ^ "Föreskrifter om ändring i Läkemedelsverkets föreskrifter (LVFS 2011:10) om förteckningar över narkotika" [Regulations amending the Medical Products Agency's regulations (LVFS 2011: 10) on lists of drugs] (PDF). Läkemedelsverkets (The Medical Products Agency) (in Swedish). 11 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- ^ "衛生福利部食品藥物管理署". 25 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Drugs and controlled medicines | The Official Portal of the UAE Government". u.ae. Archived from the original on 2024-01-25. Retrieved 2024-01-25.