Bengalis

| |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 280–290 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,542,083 (2020)[4] | |

| 2,000,000[5] | |

| 1,089,917[6] | |

| 1,015,389 (2021)[7][8] | |

| 516,076 (2020)[9] | |

| 350,000[10] | |

| 221,000[11] | |

| 200,000[12] | |

| 135,000[13] | |

| 100,000[14] | |

| 97,115[15] | |

| 70,000[16] | |

| 69,420[17] | |

| 54,566[18] | |

| 26,582[19] | |

| 16,655[20] | |

| 12,374[21] | |

| 8,500[22] | |

| 8,000[23] | |

| Languages | |

| Majority: Bengali and its dialects Minority: Urdu | |

| Religion | |

Christians, Buddhists and Other (0.8%) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

| Cuisine |

Bengalis (Bengali: বাঙালি/বাঙ্গালী Bengali pronunciation: [baŋali/baŋgali]), also rendered as Bangali[24] or the Bengali people,[25] are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the Bengal region of South Asia The population is divided between the independent country Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley. Most of them speak Bengali, a language from the Indo-Aryan language family. The term "Bangalee" is also used to refer to the people of Bangladesh.[26]

Bengalis are the third-largest ethnic group in the world, after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[27] Thus, they are the largest ethnic group within the Indo-Europeans. Apart from Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam's Barak Valley, Bengali-majority populations also reside in India's union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, with significant populations in the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttarakhand as well as Nepal's Province No. 1.[28] The global Bengali diaspora (Bangladeshi diaspora and Indian Bengalis) have well-established communities in the Middle East, Pakistan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Malaysia, Italy, Singapore, Maldives, Canada, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

Along with national grouping, Bengalis can also be divided into four major religious subgroups in descending order: Bengali Muslims, Bengali Hindus, Bengali Buddhists, and Bengali Christians.

Name

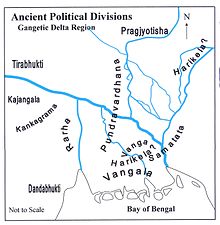

The term Bengali is generally used to refer to the someone whose linguistic, cultural or ancestral origins are from Bengal. The Indo-Aryan Bengalis are ethnically differentiated from the non-Indo-Aryan tribes inhabiting Bengal. Their ethnonym, Bangali, along with the native name of the language and region Bangla, are both derived from Bangālah, the Persian word for the region. Prior to Muslim expansion, there was no unitary territory by this name as the region was instead divided into numerous geopolitical divisions. The most prominent of these were Vanga (from which Bangalah is thought to ultimately derive from) in the south, Rarh in the west, Pundravardhana and Varendra in the north, and Samatata and Harikela in the east. In ancient times, the people of this region identified themselves with respect to these divisions. Vedic texts such as the Mahabharata makes mention of the Pundra people.

The land of Vanga (bôngô in Bengali) is considered by both Abrahamic and Dharmic traditions to have originated from a man who had settled in the area. Abrahamic genealogists suggest that the area was first colonised by Bang, a son of Hind who was the son of Ham (son of Noah).[29][30] In contrast, the Mahabharata, Puranas and the Harivamsha state that Vanga was the founder of the Vanga Kingdom and one of the adopted sons of King Vali. The land of Vanga later came to be known as Vangāla (Bôngal) and its earliest reference is in the Nesari plates (805 CE) of Govinda III which speak of Dharmapala as its king. The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, speak of Govindachandra as the ruler of Vangaladesa (a Sanskrit cognate to the word Bangladesh, which was historically a synonymous endonym of Bengal).[31][32] 16th-century historian Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak mentions in his Ain-i-Akbari that the addition of the suffix "al" came from the fact that the ancient rajahs of the land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al".[33] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyaz-us-Salatin.[34]

In 1352 CE, a Muslim nobleman by the name of Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah united the region into a single political entity known as the Bengal Sultanate. Proclaiming himself as Shāh-i-Bangālīyān,[35] it was in this period that the Bengali language also gained state patronage and corroborated literary development.[36][37] Thus, Ilyas Shah had effectively formalised the socio-linguistic identity of the region's inhabitants as Bengali, by state, culture and language.[38]

History

Ancient history

Archaeologists have discovered remnants of a 4,000-year-old Chalcolithic civilisation in the greater Bengal region, and believe the finds are one of the earliest signs of settlement in the region.[39] However, evidence of much older Palaeolithic human habitations were found in the form of a stone implement and a hand axe in Rangamati and Feni districts of Bangladesh.[40]

Artefacts suggest that the Wari-Bateshwar civilisation, which flourished in present-day Narsingdi, date as far back as 2000 BC. Not far from the rivers, the port city was believed to have been engaged in foreign trade with Ancient Rome, Southeast Asia and other regions. The people of this civilisation live in bricked homes, walked on wide roads, used silver coins and iron weaponry among many other things. It is thought to be the oldest city in Bengal and in the eastern part of the subcontinent as a whole.[41]

It is thought that a man named Vanga settled in the area around 1000 BCE founding the Vanga Kingdom in southern Bengal. The Atharvaveda and the Hindu epic Mahabharata mentions this kingdom, along with the Pundra Kingdom in northern Bengal. The spread of Mauryan territory and promotion of Buddhism by its emperor Ashoka cultivated a growing Buddhist society among the people of present-day Bengal from the 2nd century BCE, mentioning the people of this region as supporters of Buddhism at the Great Stupa of Sanchi. The Buddhists of Bengal built and utilised dozens of monasteries, and were recognised for their religious commitments as far as Nagarjunakonda in South India.[42]

One of the earliest foreign references to Bengal is the mention of a land ruled by the king Xandrammes named Gangaridai by the Greeks around 100 BCE. The word is speculated to have come from Gangahrd ('Land with the Ganges in its heart') in reference to an area in Bengal.[43] Later from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, the kingdom of Magadha served as the seat of the Gupta Empire.

Middle Ages

One of the first recorded independent kings of Bengal was Shashanka, reigning around the early 7th century.[44] After a period of anarchy, Gopala I came to power in 750. He founded the Buddhist Pala Empire.[45] Atiśa, a renowned Buddhist teacher from eastern Bengal, was instrumental in the revival of Buddhism in Tibet and also held the position of Abbot at the Vikramashila monastery in Bihar.

The Pala Empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire, and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Middle East.[46] The people of Samatata, in southeastern Bengal, during the 10th-century were of various religious backgrounds. Tilopa was a prominent Hindu priest from modern-day Chittagong, though Samatata was ruled by the Buddhist Chandra dynasty. During this time, the Arab geographer Al-Masudi and author of The Meadows of Gold, travelled to the region where he noticed a Muslim community of inhabitants residing in the region.[47] In addition to trade, Islam was also being introduced to the people of Bengal through the migration of Sufi missionaries prior to conquest. The earliest known Sufi missionaries were Syed Shah Surkhul Antia and his students, most notably Shah Sultan Rumi, in the 11th century. Rumi settled in present-day Netrokona, Mymensingh where he influenced the local ruler and population to embrace Islam.

The Pala dynasty was later followed by a shorter reign of the Hindu Sena Empire. Subsequent Muslim conquests helped spread Islam throughout the region.[48] Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turkic general, defeated Lakshman Sen of the Sena dynasty and conquered large parts of Bengal. Consequently, the region was ruled by dynasties of sultans and feudal lords under the Bengal Sultanate for the next few hundred years. Many of the people of Bengal began accepting Islam through the influx of missionaries following the initial conquest. Sultan Balkhi and Shah Makhdum Rupos settled in the present-day Rajshahi Division in northern Bengal, preaching to the communities there. A community of 13 Muslim families headed by Burhanuddin also existed in the northeastern Hindu city of Srihatta (Sylhet), claiming their descendants to have arrived from Chittagong.[49] By 1303, hundreds of Sufi preachers led by Shah Jalal aided the Muslim rulers in Bengal to conquer Sylhet, turning the town into Jalal's headquarters for religious activities. Following the conquest, Jalal disseminated his followers across different parts of Bengal to spread Islam, and became a household name among Bengali Muslims.

The establishment of a single united Bengal Sultanate in 1352 by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah finally gave rise to a "Bengali" socio-linguistic identity.[50] The Ilyas Shahi dynasty acknowledged Muslim scholarship, and this transcended ethnic background. Usman Serajuddin, also known as Akhi Siraj Bengali, was a native of Gaur in western Bengal and became the Sultanate's court scholar during Ilyas Shah's reign.[51][52][53] Alongside Persian and Arabic, the sovereign Sunni Muslim nation-state also enabled the language of the Bengali people to gain patronage and support, contrary to previous states which exclusively favoured Sanskrit, Pali and Persian.[36][37] The born-Hindu Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah funded the construction of Islamic institutions as far as Mecca and Madina in the Middle East. The people of Arabia came to know these institutions as al-Madaris al-Bangaliyyah (Bengali madrasas).

Mughal era

The Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the 16th century, ending the independent Sultanate of Bengal and defeating Bengal's rebellion Baro-Bhuiyan chieftains. Mughal general Man Singh conquered parts of Bengal including Dhaka during the time of Emperor Akbar. A few Rajput tribes from his army permanently settled around Dhaka and surrounding lands, integrating into Bengali society. Akbar's preaching of the syncretic Din-i Ilahi, was described as a blasphemy by the Qadi of Bengal, which caused huge controversies in South Asia. By the early 17th century, Islam Khan I had conquered all of Bengal. Bengal was integrated into a province of the Empire, known as the Bengal Subah. It was the largest subdivision of the Mughal Empire, as it also encompassed parts of Bihar and Odisha, between the 16th and 18th centuries. Absorbed into one of the gunpowder empires, Bengal became the wealthiest region in the subcontinent, and its proto-industrial economy showed signs of driving an Industrial revolution.[54] Described by some as the "Paradise of Nations"[55] and the "Golden Age of Bengal",[56][57], Bengalis enjoyed some of the highest living standards and real wages in the world at the time.[58] Singlehandedly accounting for 40% of Dutch imports outside the European continent,[59][60] eastern Bengal was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[61] and was a major exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce in the world.[60] Two Bengal viceroys – Muhammad Azam Shah and Azim-ush-Shan – assumed the imperial throne.

By the 18th century, Mughal Bengal eventually became a quasi-independent monarchy state ruled by the Nawabs of Bengal. Already observing the proto-industrialization, it made direct significant contribution to the first Industrial Revolution[62][63][64][65] (substantially textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution).

Bengal became the basis of the Anglo-Mughal War.[66][67] After the weakening of the Mughal Empire with the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, Bengal was ruled independently by three dynasties of Nawabs until 1757, when the region was annexed by the East India Company after the Battle of Plassey.

British colonisation

In Bengal, effective political and military power was transferred from the old regime to the British East India Company around 1757–65.[68] Company rule in India began under the Bengal Presidency. Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1772. The presidency was run by a military-civil administration, including the Bengal Army, and had the world's sixth earliest railway network. Great Bengal famines struck several times during colonial rule, notably the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and Bengal famine of 1943, each killing millions of Bengalis.

Under British rule, Bengal experienced deindustrialisation.[64] The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was initiated on the outskirts of Calcutta, and spread to Dhaka, Chittagong, Jalpaiguri, Sylhet and Agartala, in solidarity with revolts in North India. The failure of the rebellion led to the abolishment of the Mughal Court and direct rule by the British Raj.

Many Bengali laborers were taken as coolies to the British colonies in the Caribbean during the 1830s. Workers from Bengal were chosen because they could easily assimilate to the climate of British Guyana, which was similar to that of Bengal.

Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America,[69] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, and bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the 1800s.[70]

Independence movement

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant. Many of the early proponents of the independence struggle, and subsequent leaders in the movement were Bengalis such as Surendranath Banerjea, Dudu Miyan, Titumir, Prafulla Chaki, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Binoy-Badal-Dinesh, Sarojini Naidu, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose, and Sachindranath Sanyal.

Some of these leaders, such as Netaji, did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the best way to achieve Indian Independence, and were instrumental in armed resistance against the British force. Netaji was the co-founder and leader of the Japanese-aligned Indian National Army (distinct from the army of British India) that challenged British forces in several parts of India. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime, the Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind. Bengal was also the fostering ground for several prominent revolutionary organisations, the most notable of which was Anushilan Samiti. A number of Bengalis died during the independence movement and many were imprisoned in Cellular Jail, the notorious prison in Andaman.

Partitions of Bengal

The first partition in 1905 divided the Bengal region in British India into two provinces for administrative and development purposes. However, the partition stoked Hindu nationalism. This in turn led to the formation of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906 to represent the growing aspirations of the Muslim population. The partition was annulled in 1912 after protests by the Indian National Congress and Hindu Mahasabha.

The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity in India drove the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution in 1943, calling the creation of "independent states" in eastern and northwestern British India. The resolution paved the way for the Partition of British India based on the Radcliffe Line in 1947, despite attempts to form a United Bengal state that was opposed by many people.

Bangladesh Liberation War

The rise of self-determination and Bengali nationalism movements in East Bengal, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War against the Pakistani military junta. Upwards of an estimated 3 million (3,000,000) people died in the conflict, particularly as a result of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. The war caused millions of East Bengali refugees to take shelter in neighboring India, especially the Indian state of West Bengal, with Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal, becoming the capital-in-exile of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. The Mukti Bahini guerrilla forces waged a nine-month war against the Pakistani military. The conflict ended after the Indian Armed Forces intervened on the side of Bangladeshi forces in the final two weeks of the war, which ended with the Surrender of Pakistan and the liberation of Dhaka on 16 December 1971. Thus the newly independent People's Republic of Bangladesh was born from what was previously the East Pakistan province of Pakistan.

Diaspora

From the earliest times, Bengali people have left Bengal to settle in other parts of the world. Bengali ethnic descent and emigrant communities are found primarily in other parts of the subcontinent, the Middle East and the Western World. Substantial populations descended from Bengali immigrants exist in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United Kingdom where they form established communities of over 1 million people. Majority of the Bengali diaspora belong to the Muslim faith as the act of seafaring was traditionally prohibited in Hinduism; a taboo known as kala pani (black/dirty water).[71]

The introduction of Islam to the Bengali people has generated a connection to the Arabian Peninsula, as Muslims are required to visit the land once in their lifetime to complete the Hajj pilgrimage. Several Bengali sultans funded Islamic institutions in the Hejaz, which popularly became known by the Arabs as Bangali Madaris. It is unknown when Bengalis began settling in Arab lands though an early example is that of Haji Shariatullah's teacher Mawlana Murad, who was permanently residing in the city of Mecca in the early 1800s.[72] Notable people of Bengali-origin that live in the Middle East include Zohurul Hoque, a translator of the Qur'an who lives in Oman, as well as the family of Princess Sarvath al-Hassan, who is the wife of Jordanian prince Hassan bin Talal.

Earliest records of Bengalis in the European continent date back to the reign of King George III of England during the 16th-century. One such example is I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim cleric from Nadia in western Bengal, who arrived to Europe in 1765 with his servant Muhammad Muqim as a diplomat for the Mughal Empire.[73] Another example during this period is of James Achilles Kirkpatrick's hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) who was said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man, presumably from Sylhet in eastern Bengal, was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.[74] Today, the British Bangladeshis are a naturalised community in the United Kingdom, running 90% of all South Asian cuisine restaurants and having established numerous ethnic enclaves across the country – most prominent of which is Banglatown in East London.[75]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

Festivals

Bengalis commemorate the Islamic holidays or Hindu festivals depending on their religion. People are dressed in their new traditional clothing.[76] Children are given money and gifts by elders. They will then visit their relatives later in the day. Traditional food will be cooked for relatives, such as samosa and shemai. These celebrations reunite relatives and improve relations.[77]

Significant cultural events or celebrations are also celebrated by the community annually. Pohela Boishakh is a celebration of the new year and arrival of summer in the Bengali calendar and is celebrated in April. It features a funfair, music and dance displays on stages, with people dressed in colourful traditional clothes, parading through the streets.[78] Festivals like Pahela Falgun (spring) are also celebrated regardless of their faith. The Bengalis of Dhaka celebrate Shakrain, an annual kite festival. The Nabanna is a Bengali celebration akin to the harvest festivals in the Western world.

Fashion and arts

Visual art and architecture

The recorded history of art in Bengal can be traced to the 3rd century BCE, when terracotta sculptures were made in the region. The architecture of the Bengal Sultanate saw a distinct style of domed mosques with complex niche pillars that had no minarets. Ivory, pottery and brass were also widely used in Bengali art.

Attire and clothing

Bengali attire is shares similarities with North Indian attire. In rural areas, older women wear the shari while the younger generation wear the selwar kamiz, both with simple designs. In urban areas, the selwar kamiz is more popular, and has distinct fashionable designs. Traditionally Bengali men wore the jama, though the costumes such as the panjabi with selwar or pyjama have become more popular within the past three centuries. The popularity of the fotua, a shorter upper garment, is undeniable among Bengalis in casual environments. The lungi and gamcha are a common combination for rural Bengali men. Islamic clothing is also very common in the region. During special occasions, Bengali women commonly wear either sharis, selwar kamizes or abayas, covering their hair with hijab or orna; and men wear a panjabi, also covering their hair with a tupi, toqi, pagri or rumal.

Mughal Bengal's most celebrated artistic tradition was the weaving of Jamdani motifs on fine muslin, which is now classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. Jamdani motifs were similar to Iranian textile art (buta motifs) and Western textile art (paisley). The Jamdani weavers in Dhaka received imperial patronage.[60][79]

Performing arts

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (May 2017) |

Bengali theatre traces its roots to Sanskrit drama under the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE. It includes narrative forms, song and dance forms, supra-personae forms, performance with scroll paintings, puppet theatre and the processional forms like the Jatra. Bengal has an extremely rich heritage of dancing dating back to antiquity. It includes classical, folk and martial dance traditions.[80][81]

Gastronomy

Bengali cuisine is the culinary style of the Bengali people. It has the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from South Asia that is analogous in structure to the modern service à la russe style of French cuisine, with food served course-wise rather than all at once. The dishes of Bengal are often centuries old and reflect the rich history of trade in Bengal through spices, herbs, and foods. With an emphasis on fish and vegetables served with rice as a staple diet, Bengali cuisine is known for its subtle flavours, and its huge spread of confectioneries and milk-based desserts. One will find the following items in most dishes; mustard oil, fish, panch phoron, lamb, onion, rice, cardamom, yogurt and spices. The food is often served in plates which have a distinct flowery pattern often in blue or pink. Common beverages include shorbot, borhani, ghol, matha, lachhi, falooda, Rooh Afza, natural juices like Akher rosh, Khejur rosh, Aamrosh, Dudh cha, Taler rosh, Masala cha, as well as basil seed or tukma-based drinks.

West Bengali and East Bengali cuisines have many similarities, but also many unique traditions at the same time. These kitchens have been influenced by the history of the respective regions. The kitchens can be further divided into the urban and rural kitchens. Urban kitchens in eastern Bengal consist of native dishes with foreign Mughal influence, for example the Haji biryani and Chevron Biryani of Old Dhaka.

Language

An important and unifying characteristic of Bengalis is a common language. Bengali is an Indo-Aryan language and is also a lingua franca among other ethnic groups and tribes living in and around the Bengal region. It is generally written using the Bengali script and evolved circa 1000–1200 CE from Magadhi Prakrit. With about 226 million native and about 300 million total speakers worldwide, Bengali is one of the most spoken languages, ranked sixth in the world.[82][83]

Bengali has developed into numerous distinct forms which can be categorised into three. Sadhu Bengali is the historical form used in literary texts up until the late British period. Colloquial Bengali, an informal spoken language, varies by dialect from region to region (see below); various forms of the language are in use today and provide an important force for Bengali cohesion. Standard Bengali is the modern literary form, and it is based on the dialects of the Nadia region (partitioned between Nadia and Kushtia). It is used today in writing and in formal speaking, for example, prepared speeches, some radio broadcasts, and non-entertainment content.

Bengali people may be broadly classified into sub-groups predominantly based on dialect but also other aspects of culture:

- Bangals: This is a term used predominantly in Indian West Bengal to refer to East Bengalis – i.e. Bangladeshis as well as those whose ancestors originate from Eastern Bengal. The East Bengali dialects are known as Bangali. This group constitutes the majority of ethnic Bengalis. They originate from the mainland Bangladeshi regions of Dhaka, Mymensingh, Comilla and Barisal as well as Bengali-speaking areas in Assam and Tripura.

- Chittagonians are natives of the Chittagong region (Chittagong District and Cox's Bazar District) of Bangladesh and speak Chittagonian. The people of Cox's Bazar are closely related to the Rohingya. Sylhetis originate from the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh and the Barak Valley in India, and they speak Sylheti. Noakhailla speakers can be found in greater Noakhali region and southern Tripura. The Puran Dhakaiyas are a small urban community residing in Old Dhaka that noticeably differ from the rest of the people of Dhaka Division by language and culture. These four groups maintain distinct identities in addition to having a (East) Bengali identity.[84][85]

- Ghotis: This is the term favoured by the natives of West Bengal to distinguish themselves from other Bengalis.

- The region of North Bengal, which hosts Varendri and Rangpuri speakers, is divided between both West Bengal and Bangladesh, and they are normally categorised into the former two main groups depending on which side of the border they reside in even though they are culturally similar to each other regardless of international borders. The categorisation of North Bengalis into Ghoti or Bangal is contested.

Literature

Bengali literature denotes the body of writings in the Bengali language, which has developed over the course of roughly 13 centuries. The earliest extant work in Bengali literature can be found within the Charyapada, a collection of Buddhist mystic hymns dating back to the 10th and 11th centuries. They were discovered in the Royal Court Library of Nepal by Hara Prasad Shastri in 1907. The timeline of Bengali literature is divided into three periods − ancient (650-1200), medieval (1200-1800) and modern (after 1800). Medieval Bengali literature consists of various poetic genres, including Islamic epics by the likes of Abdul Hakim and Syed Sultan, secular texts by Muslim poets like Alaol and Vaishnava texts by the followers of Krishna Chaitanya. Bengali writers began exploring different themes through narratives and epics such as religion, culture, cosmology, love and history. Royal courts such as that of the Bengal Sultanate and the Kingdom of Mrauk U gave patronage to numerous Bengali writers such as Daulat Qazi and Dawlat Wazir Bahram Khan.

The Bengali Renaissance refers to a socio-religious reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, centered around the city of Calcutta and predominantly led by upper-caste Bengali Hindus under the patronage of the British Raj who had created a reformed religion known as the Brahmo Samaj. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes the Bengal renaissance as having begun with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833) and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[65]

Though the Bengal Renaissance was predominantly representative to the Hindu community due to their relationship with British colonisers,[86] there were, nevertheless, examples of modern Muslim littérateurs in this period. Mir Mosharraf Hossain (1847–1911) was the first major writer in the modern era to emerge from the Bengali Muslim society, and one of the finest prose writers in the Bengali language. His magnum opus Bishad Shindhu is a popular classic among Bengali readership. Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), notable for his activism and anti-British literature, was described as the Rebel Poet and is now recognised as the National poet of Bangladesh. Begum Rokeya (1880-1932) was the leading female Bengali author of this period, best known for writing Sultana's Dream which was subsequently translated into numerous languages. The Freedom of Intellect Movement sought to challenge religious and social dogma in Bengali Muslim society.[citation needed]

Religion

The largest religions practiced in Bengal are Islam and Hinduism. Among all Bengalis, more than two thirds are Muslims. The Bengali Muslims form a 90.4% majority in Bangladesh,[87] and a 30% minority among the Bengalis in eastern India.[88][89][90][91][92] In West Bengal, Bengali Muslims form a 66.88% majority in Murshidabad district, the former seat of the Nawabs of Bengal, a 51.27% majority in Malda, which contains the erstwhile capitals of the Bengal Sultanate and number over 5,487,759 in the 24 Parganas.[93]

Just less than a third of all Bengalis are Hindus, and they form a 70.5% majority in West Bengal and a 8.4% minority in Bangladesh.[94][91] In Bangladesh, Hindus are mostly concentrated in Sylhet Division where they constitute 17.8% of the population, and are mostly populated in Chittagong Division where they number over 3,000,000. Hindus form a 56.41% majority in Dacope Upazila, a 51.69% majority in Kotalipara Upazila and a 51.22% majority in Sullah Upazila. In terms of population, Bangladesh is the third largest Hindu populated country of the world, just after India and Nepal. The total Hindu population in Bangladesh exceeds the population of many Muslim majority countries like Yemen, Jordan, Tajikistan, Syria, Tunisia, Oman, and others.[95] Also the total Hindu population in Bangladesh is roughly equal to the total population of Greece and Belgium.[96]

Other religious groups include Buddhists (comprising around 1% of the population in Bangladesh) and Bengali Christians.[92]

Science

The Bengali contributions to modern science is path breaking in the world's context. Meghnad Saha contributed to the theorisation of Thermal ionization.

Qazi Azizul Haque was a Bengali inventor who is credited for devising the mathematical basis behind a fingerprint classification system that continued to be used up until the 1990s for criminal investigations.

Satyendra Nath Bose was a Bengali physicist, specialising in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson. He made first calculations to initiate Statistical Mechanics. He first hypothesised a physically tangible idea of photon.

Jagadish Chandra Bose was a Bengali polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction[97] who pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[98] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[99] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. He first practicalised the wireless radio transmission. But Marconi got recognition for European proximity. He also described for the first time that "plants can respond", by demonstrating with his crescograph, recording the impulse caused by bromination of plant tissue.

Sport and games

Cricket and football are the most popular sports amongst Bengalis. The British Regimental teams introduced the sports to the community, who took it up very enthusiastically. The oldest Football Club formed in Bengal was Mohun Bagan, which was founded in 1889, by the eminent lawyer Bhupendra Nath Bose. The first major victory for Bengali football came in 1911, when Mohun Bagan beat Yorkshire Regiment to win the IFA Shield Cup. The popularity of Football was immediately boosted in Bengal. The people of Pre – Independence Bengal saw it as a way to challenge the superiority of the British. The view of Bengalis at the time of being lazy, weak people quickly changed, into a more muscular, ravishing one. This was the birth of football in Bengal.In Kolkata Football, Mohun Bagan's major rival is East Bengal F.C which was founded in 1920. The Hindu immigrants from across the border, who had been forced to move post – partition, supported this club. This rivalry also portrayed the societal problems at that time. The original residents of the city supported Mohun Bagan, and hated the immigrants, though Hindu, from modern day Bangladesh – who supported East Bengal. There were many famous encounters between theses two famous clubs, some of whose recounts can be found on the internet. In the city of Kolkata, the other major Football Club is Mohammedan SC. Hamza Choudhury is the first Bengali to play in the Premier League and is predicted to be the first British Asian to play for the England national football team.[100]

Bengalis are very competitive when it comes to board and home games such as Pachisi and its modern counterpart Ludo, as well as Carrom Board, Chor-Pulish, Kanamachi and Chess. Rani Hamid is one of the most successful chess players in the world, winning championships in Asia and Europe multiple times. Ramnath Biswas was a revolutionary soldier who embarked on three world tours on a bicycle in the 19th century. Bengali fighting sports and martial arts include Kabaddi, Butthan, Latim, Mokkar Boli Khela, Lathi khela and Jobbarer Boli Khela.

The Nouka Baich is a traditional boat racing competition which takes place during and after the rainy season when much of the land goes under water. The long canoes were referred to as khel naos (meaning playing boats) and the use of cymbals to accompany the singing was common. Different types of boats are used in different parts of Bengal.[101]

Political culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (May 2017) |

Bengalis are very active in politics of their region. In Bangladesh, the Prime Minister of the nation is Sheikh Hasina, belonging to the Awami League party. In West Bengal, India, the chief minister of state is Mamata Banerjee from the party All India Trinamool Congress.

See also

- Bengali nationalism

- List of Bangladeshis

- List of Bengalis

- List of people from West Bengal

- States of India by Bengali speakers

References

- ^ Bengalis at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Bengalis at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

Bengalis at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)  Note: As per discussion on talk page the range is provided since we don't have reliable source for exact number on ethnic group. The range figures are calculated on the basis of L1 speakers, whereas L2 speakers are omitted as they non-Bengalis.

Note: As per discussion on talk page the range is provided since we don't have reliable source for exact number on ethnic group. The range figures are calculated on the basis of L1 speakers, whereas L2 speakers are omitted as they non-Bengalis.

- ^ "South Asia :: Bangladesh". Cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- ^ "Asians in the Middle East" (PDF). Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations.

- ^ —"Five million illegal immigrants residing in Pakistan". Express Tribune.

—"Homeless In Karachi". Outlook. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

—"Falling back". Daily Times. 17 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

—van Schendel, Willem (2005). The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. Anthem Press. p. 250. ISBN 9781843311454. - ^ "Migration Profile – UAE" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Resident Population Estimates by Ethnic Group, All Persons: All Persons; All Ages; Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi (Persons)". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ [1] 2011 Census: Ethnic Group, local authorities in the United Kingdom, 11 October 2013, accessed 19 September 2016.

- ^ "ASIAN ALONE OR IN ANY COMBINATION BY SELECTED GROUPS: 2015". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Bhuyan, Md Owasim Uddin (21 March 2020). "Bangladeshi migrants trapped in Qatar labour camp lockdown". New Age. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Aina Nasa (27 July 2017). "More than 1.7 million foreign workers in Malaysia; majority from Indonesia". New Straits Times. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Kuwait restricts recruitment of male Bangladeshi workers". Dhaka Tribune. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "In pursuit of happiness". Korea Herald. 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Bangladeshis in Singapore". High Commission of Bangladesh, Singapore. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Bahrain: Foreign population by country of citizenship". gulfmigration.eu. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Nahar, K (13 June 2011), "Maldives to deport thousands of illegal Bangladeshi workers", The Financial Express, Dhaka, retrieved 16 July 2011,

Maldivian foreign minister Ahmed Naseem last week said some 70,000 Bangladeshi are now working in his country --- a nation of only around 300,000 people --- with one-third having no valid documents or registration.

- ^ "NHS Profile, Canada, 2011, Census Data". Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Census shows Indian population and languages have exponentially grown in Australia". SBS Australia. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Population Monograph of Nepal: Volume II (Social Demography)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ バングラデシュ人民共和国(People's Republic of Bangladesh). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) (in Japanese). Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ 체류외국인 국적별 현황, 2013년도 출입국통계연보, South Korea: Ministry of Justice, 2013, p. 290, retrieved 5 June 2014

- ^ http://www.qatar-tribune.com/news.aspx?n=659B1F3A-7299-4D4A-B2DA-D3BAA8AE673D&d=20150625[permanent dead link]

- ^ https://www.dfa.ie/travel/travel-advice/a-z-list-of-countries/bangladesh/

- ^ "Part I: The Republic - The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Bangalees and indigenous people shake hands on peace prospects". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh | 6. Citizenship". bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: zero width joiner character in|title=at position 33 (help) - ^ roughly 163 million in Bangladesh and 100 million in India (CIA Factbook 2014 estimates, numbers subject to rapid population growth); about 3 million Bangladeshis in the Middle East, 2 million Bengalis in Pakistan, 0.4 million British Bangladeshi.

- ^ "50th REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Blood, Peter R. (1989). "Early History, 1000 B. C.-A. D. 1202". In Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L. (eds.). Bangladesh: A country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 4.

- ^ Ahmed, Helal Uddin (2012). "History". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 281. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ^ Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- ^ RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Ghulam Husain Salim, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902.

- ^ Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Iliyas Shah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b "What is more significant, a contemporary Chinese traveler reported that although Persian was understood by some in the court, the language in universal use there was Bengali. This points to the waning, although certainly not yet the disappearance, of the sort of foreign mentality that the Muslim ruling class in Bengal had exhibited since its arrival over two centuries earlier. It also points to the survival, and now the triumph, of local Bengali culture at the highest level of official society." (Eaton 1993:60)

- ^ a b Rabbani, AKM Golam (7 November 2017). "Politics and Literary Activities in the Bengali Language during the Independent Sultanate of Bengal". Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics. 1 (1): 151–166. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017 – via www.banglajol.info.

- ^ Murshid, Ghulam (2012). "Bangali Culture". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "4000-year old settlement unearthed in Bangladesh". Xinhua. 12 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007.

- ^ "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association @ TTU. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ "বেলাব উপজেলার পটভূমি" [Belabo Upazila's Background]. Belabo Upojela (in Bengali).

- ^ (Eaton 1993)

- ^ Chowdhury, AM (2012). "Gangaridai". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, PK (2012). "Shashanka". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- ^ Al-Masudi, trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille (1962). "1:155". In Pellat, Charles (ed.). Les Prairies d’or [Murūj al-dhahab] (in French). Paris: Société asiatique.

- ^ Abdul Karim (2012). "Islam, Bengal". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Qurashi, Ishfaq (December 2012). "বুরহান উদ্দিন ও নূরউদ্দিন প্রসঙ্গ" [Burhan Uddin and Nooruddin]. শাহজালাল(রঃ) এবং শাহদাউদ কুরায়শী(রঃ) [Shah Jalal and Shah Dawud Qurayshi] (in Bengali).

- ^ Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Iliyas Shah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ 'Abd al-Haqq al-Dehlawi. Akhbarul Akhyar.

- ^ Abdul Karim (2012). "Shaikh Akhi Sirajuddin Usman (R)". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Hanif, N (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. Prabhat Kumar Sharma, for Sarup & Sons. p. 35.

- ^ Lex Heerma van Voss; Els Hiemstra-Kuperus; Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk (2010). "The Long Globalization and Textile Producers in India". The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000. Ashgate Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9780754664284.

- ^ Steel, Tim (19 December 2014). "The paradise of nations". Op-ed. Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Pakistan Quarterly. 1956.

- ^ Islam, Sirajul (1992). History of Bangladesh, 1704-1971: Economic history. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-512-337-2.

- ^ M. Shahid Alam (2016). Poverty From The Wealth of Nations: Integration and Polarization in the Global Economy since 1760. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-333-98564-9.

- ^ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- ^ a b c Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed).

- ^ Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ Junie T. Tong (2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ John L. Esposito, ed. (2004). The Islamic World: Past and Present. Vol. Volume 1: Abba - Hist. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ a b Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

The Bengal Renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).

- ^ Hasan, Farhat (1991). "Conflict and Cooperation in Anglo-Mughal Trade Relations during the Reign of Aurangzeb". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 34 (4): 351–360. doi:10.1163/156852091X00058. JSTOR 3632456.

- ^ Vaugn, James (September 2017). "John Company Armed: The English East India Company, the Anglo-Mughal War and Absolutist Imperialism, c. 1675–1690". Britain and the World. 11 (1).

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Georg, Feuerstein (2002). The Yoga Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 600. ISBN 978-3-935001-06-9.

- ^ Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006). New Religions in Global Perspective. Routledge. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7007-1185-7.

- ^ "Crossing the Kala Pani to Britain for Hindu Workers and Elites". American Historical Association. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ The Muslim Society and Politics in Bengal, A.D. 1757-1947. University of Dacca. 1978. p. 76.

Maulana Murad , a Bengali domicile

- ^ C.E. Buckland, Dictionary of Indian Biography, Haskell House Publishers Ltd, 1968, p.217

- ^ Colebrooke, Thomas Edward (1884). "First Start in Diplomacy". Life of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9781108097222.

- ^ Khaleeli, Homa (8 January 2012). "The curry crisis". The Guardian.

- ^ Sarah C., White (1992). Arguing with the Crocodile: Gender and Class in Bangladesh. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-85649-085-6.

- ^ Gilbert, Pamela K (2002). Imagined Londons. p. 170. ISBN 0-7914-5502-5.

- ^ "Banglatown spices it up for the new year". The Londoner. Archived from the original on 1 May 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ "In Search of Bangladeshi Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Hasan, Sheikh Mehedi (2012). "Dance". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Ahmed, Wakil (2012). "Folk Dances". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue. 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Huq, Mohammad Daniul & Sarkar, Pabitra (2012). "Bangla Language". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tanweer Fazal (2012). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia: 'We are with culture but without geography': locating Sylheti identity in contemporary India, Nabanipa Bhattacharjee.' pp.59–67.

- ^ A community without aspirations Zia Haider Rahman. 2 May 2007. Retrieved on 7 March 2018.

- ^ Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 213. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

- ^ 2014 US Department of State estimates

- ^ Comparing State Polities: A Framework for Analyzing 100 Governments By Michael J. III Sullivan, pg. 119

- ^ "BANGLADESH 2015 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Andre, Aletta; Kumar, Abhimanyu (23 December 2016). "Protest poetry: Assam's Bengali Muslims take a stand". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Total Muslim population in Assam is 34.22% of which 90% are Bengali Muslims according to this source which puts the Bengali Muslim percentage in Assam as 29.08%

- ^ a b Bangladesh- CIA World Factbook

- ^ a b "C-1 Population By Religious Community - West Bengal". census.gov.in. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Population by religious community: West Bengal. 2011 Census of India.

- ^ "Population Housing Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "[Analysis] Are there any takeaways for Muslims from the Narendra Modi government?". DNA. 27 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Haider, M. Moinuddin; Rahman, Mizanur; Kamal, Nahid (6 May 2019). "Hindu Population Growth in Bangladesh: A Demographic Puzzle". Journal of Religion and Demography. 6 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1163/2589742X-00601003. ISSN 2589-7411.

- ^ "A versatile genius". Frontline. Vol. 21, no. 24. 3 December 2004. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ^ Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- ^ Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest. IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. Denver, CO: IEEE. pp. 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- ^ Trehan, Dev (2 September 2019). "Hamza Choudhury can be first British South Asian to play for England, says Michael Chopra". Sky Sports.

- ^ S M Mahfuzur Rahman (2012). "Boat Race". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

Further reading

- Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Sarkar, Prabhat Ranjan (1988). Bangla o Bangali. Ananda Marga Publications. p. 441. ISBN 978-81-7252-297-1.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 554. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

- Ray, R. (1994). History of the Bengali People. Orient BlackSwan. p. 656. ISBN 978-0863113789.

- Ray, Niharranjan (1994). History of the Bengali people: ancient period. University of Michigan: Orient Longmans. p. 613. ISBN 9780863113789.

- Ray, N (2013). History of the Bengali People from Earliest Times to the Fall of the Sena Dynasty. Orient Blackswan Private Limited. p. 613. ISBN 978-8125050537.

- Das, S.N. (1 December 2005). The Bengalis: The People, Their History and Culture. p. 1900. ISBN 978-8129200662.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin UK. p. 656. ISBN 9788184755305.

- Nasrin, Mithun B; Van Der Wurff, W.A.M (2015). Colloquial Bengali. Routledge. p. 288. ISBN 9781317306139.

- Sengupta, Debjani (22 October 2015). The Partition of Bengal: Fragile Borders and New Identities. Cambridge University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-1107061705.

- Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Shubhra (1 February 2000). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis (Historical Dictionaries of Peoples and Cultures). Scarecrow Press. p. 604. ISBN 978-0810853348.

- Chatterjee, Pranab (2009). A Story of Ambivalent Modernization in Bangladesh and West Bengal: The Rise and Fall of Bengali Elitism in South Asia. Peter Lang. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4331-0820-4.

- Singh, Kumar Suresh (2008). People of India: West Bengal, Volume 43, Part 1. University of Virginia: Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1397. ISBN 9788170463009.

- Milne, William Stanley (1913). A Practical Bengali Grammar. Asian Educational Services. p. 561. ISBN 9788120608771.

- Alexander, Claire; Chatterji, Joya (10 December 2015). The Bengal Diaspora: Rethinking Muslim migration. Routledge. p. 304. ISBN 978-0415530736.

- Chakraborty, Mridula Nath (26 March 2014). Being Bengali: At Home and in the World. Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 978-0415625883.

- Sanyal, Shukla (16 October 2014). Revolutionary Pamphlets, Propaganda and Political Culture in Colonial Bengal. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-1107065468.

- Dasgupta, Subrata (2009). The Bengal Renaissance: Identity and Creativity from Rammohun Roy to Rabindranath Tagore. Permanent Black. p. 286. ISBN 978-8178242798.

- Glynn, Sarah (30 November 2014). Class, Ethnicity and Religion in the Bengali East End: A Political History. Manchester University. p. 304. ISBN 978-0719095955.

- Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. Aph Publishing Corporations. p. 365. ISBN 9788176484695.

- Deodhari, Shanti (2007). Banglar Bow (Bengali Bride). AuthorHouse. p. 80. ISBN 9781467011884.

- Gupta, Swarupa (2009). Notions of Nationhood in Bengal: Perspectives on Samaj, C. 1867-1905. BRILL. p. 408. ISBN 9789004176140.

- Roy, Manisha (2010). Bengali Women. University of Chicago Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780226230443.

- Basak, Sita (2006). Bengali Culture And Society Through Its Riddles. Neha Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 9788121208918.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2013). 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh. Harvard University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0674728646.

- Inden, Ronald B; Nicholas, Ralph W. (2005). Kinship in Bengali culture. Orient Blackswan. p. 158. ISBN 9788180280184.

- Nicholas, Ralph W. (2003). Fruits of Worship: Practical Religion in Bengal. Orient Blackswan. p. 248. ISBN 9788180280061.

- Das, S.N. (2002). The Bengalis: The People, Their History, and Culture. Religion and Bengali culture. volume 4. Cosmo Publications. p. 321. ISBN 9788177553925.

- Schendel, Willem van (2004). The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. Anthem Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-1843311447.

- Mukherjee, Janam (2015). Hungry Bengal : War, Famine, Riots and the End of Empire. Harper Collins India. p. 344. ISBN 978-9351775829.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna; Schendel, Willem van (2013). The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 568. ISBN 978-0822353188.

- Sengupta, Nitish (19 November 2012). Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971). Penguin India. p. 272. ISBN 978-0143419556.