COVID-19 pandemic

| 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

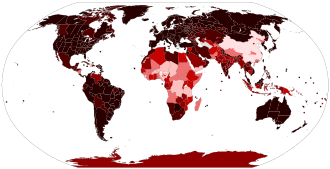

Map of confirmed cases per capita as of 23 March 2020

1000+ cases per million inhabitants

100-1000 cases per million inhabitants

10-100 cases per million inhabitants

1–10 cases per million inhabitants

0.1-1 cases per million inhabitants

>0-0.1 cases per million inhabitants

No confirmed cases | |||||||||

| |||||||||

(clockwise from top)

| |||||||||

| Disease | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | ||||||||

| Virus strain | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) | ||||||||

| Location | Worldwide (list of locations) | ||||||||

| Index case | Wuhan, Hubei, China 30°37′11″N 114°15′28″E / 30.61972°N 114.25778°E | ||||||||

| Date | 1 December 2019 – present[1] (4 years, 11 months and 2 weeks) | ||||||||

| Confirmed cases | 372,000+[2][3] | ||||||||

| Recovered | 101,000+[2][3] | ||||||||

Deaths | 16,300+[2][3] | ||||||||

Territories | 190+[2][3] | ||||||||

The 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic is an ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[4] The outbreak was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019, and was recognised as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020.[5] As of 23 March, more than 373,000 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in over 190 countries and territories, resulting in more than 16,300 deaths and over 101,000 recoveries.[2][3]

The virus is typically spread from one person to another via respiratory droplets produced during coughing.[6][7] It primarily spreads when people are in close contact but may also spread when one touches a contaminated surface and then their face.[6][7] It is most contagious when people are symptomatic, although spread may be possible before symptoms appear.[7] The time between exposure and symptom onset is typically around five days, but may range from two to fourteen days.[8][9] Common symptoms include fever, cough, and shortness of breath.[8] Complications may include pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[10] There is currently no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment.[6] Primary treatment is symptomatic and supportive therapy.[11] Recommended preventive measures include hand washing, covering the mouth when coughing, maintaining distance from other people, and monitoring and self-isolation for people who suspect they are infected.[6]

Efforts to prevent the virus spreading include travel restrictions, quarantines, curfews, event postponements and cancellations, and facility closures. These include a quarantine of Hubei, nationwide quarantines in Italy and elsewhere in Europe, curfew measures elsewhere in China and South Korea,[12][13][14] various border closures or incoming passenger restrictions,[15][16] screening at airports and train stations,[17] and travel advisories regarding regions with community transmission.[18][19][20][21] Schools and universities have closed either on a nationwide or local basis in over 124 countries, affecting more than 1.2 billion students.[22]

The pandemic has led to global socioeconomic disruption,[23] the postponement or cancellation of sporting, religious, and cultural events,[24] and widespread fears of supply shortages which have spurred panic buying.[25][26] Misinformation and conspiracy theories about the virus have spread online,[27][28] as during the time of 2009 flu pandemic lots more people were infected and died yet the mass hysteria seen for Coronavirus wasn't there [29] and there have been incidents of xenophobia and racism against Chinese and other East or Southeast Asian people.[30]

Epidemiology

| Location | Cases | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World[a] | 776,753,553 | 7,073,453 | |

| European Union[b] | 186,262,640 | 1,265,282 | |

| United States | 103,436,829 | 1,206,141 | |

| China[c] | 99,381,078 | 122,367 | |

| India | 45,044,196 | 533,653 | |

| France | 39,024,965 | 168,091 | |

| Germany | 38,437,756 | 174,979 | |

| Brazil | 37,511,921 | 702,116 | |

| South Korea | 34,571,873 | 35,934 | |

| Japan | 33,803,572 | 74,694 | |

| Italy | 26,826,486 | 197,542 | |

| United Kingdom | 25,010,212 | 232,112 | |

| Russia | 24,572,846 | 403,557 | |

| Turkey | 17,004,729 | 101,419 | |

| Spain | 13,980,340 | 121,852 | |

| Australia | 11,861,161 | 25,236 | |

| Vietnam | 11,624,000 | 43,206 | |

| Argentina | 10,106,404 | 130,697 | |

| Taiwan | 9,970,937 | 17,672 | |

| Netherlands | 8,644,647 | 22,986 | |

| Iran | 7,627,863 | 146,837 | |

| Mexico | 7,622,283 | 334,783 | |

| Indonesia | 6,829,704 | 162,059 | |

| Poland | 6,758,426 | 120,897 | |

| Colombia | 6,394,361 | 142,727 | |

| Austria | 6,082,860 | 22,534 | |

| Greece | 5,727,906 | 39,639 | |

| Portugal | 5,669,567 | 29,027 | |

| Ukraine | 5,541,305 | 109,923 | |

| Chile | 5,403,559 | 64,482 | |

| Malaysia | 5,318,418 | 37,351 | |

| Belgium | 4,889,242 | 34,339 | |

| Israel | 4,841,558 | 12,707 | |

| Canada | 4,819,055 | 55,282 | |

| Czech Republic | 4,811,887 | 43,687 | |

| Thailand | 4,803,632 | 34,734 | |

| Peru | 4,526,977 | 220,975 | |

| Switzerland | 4,468,044 | 14,170 | |

| Philippines | 4,173,631 | 66,864 | |

| South Africa | 4,072,813 | 102,595 | |

| Romania | 3,566,594 | 68,899 | |

| Denmark | 3,442,484 | 9,919 | |

| Singapore | 3,006,155 | 2,024 | |

| Hong Kong | 2,876,106 | 13,466 | |

| Sweden | 2,765,204 | 28,006 | |

| New Zealand | 2,652,096 | 4,442 | |

| Serbia | 2,583,470 | 18,057 | |

| Iraq | 2,465,545 | 25,375 | |

| Hungary | 2,236,219 | 49,092 | |

| Bangladesh | 2,051,463 | 29,499 | |

| Slovakia | 1,883,895 | 21,249 | |

| Georgia | 1,864,383 | 17,151 | |

| Republic of Ireland | 1,750,138 | 9,900 | |

| Jordan | 1,746,997 | 14,122 | |

| Pakistan | 1,580,631 | 30,656 | |

| Norway | 1,524,523 | 5,732 | |

| Kazakhstan | 1,504,370 | 19,072 | |

| Finland | 1,499,712 | 11,466 | |

| Lithuania | 1,400,088 | 9,848 | |

| Slovenia | 1,359,884 | 9,914 | |

| Croatia | 1,348,642 | 18,775 | |

| Bulgaria | 1,337,733 | 38,751 | |

| Morocco | 1,279,115 | 16,305 | |

| Puerto Rico | 1,252,713 | 5,938 | |

| Guatemala | 1,250,392 | 20,203 | |

| Lebanon | 1,239,904 | 10,947 | |

| Costa Rica | 1,235,724 | 9,374 | |

| Bolivia | 1,212,149 | 22,387 | |

| Tunisia | 1,153,361 | 29,423 | |

| Cuba | 1,113,662 | 8,530 | |

| Ecuador | 1,078,795 | 36,055 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 1,067,030 | 2,349 | |

| Panama | 1,044,987 | 8,756 | |

| Uruguay | 1,041,682 | 7,686 | |

| Mongolia | 1,011,489 | 2,136 | |

| Nepal | 1,003,450 | 12,031 | |

| Belarus | 994,038 | 7,118 | |

| Latvia | 977,765 | 7,475 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 841,469 | 9,646 | |

| Azerbaijan | 836,474 | 10,353 | |

| Paraguay | 735,759 | 19,880 | |

| Cyprus | 708,580 | 1,492 | |

| Palestine | 703,228 | 5,708 | |

| Bahrain | 696,614 | 1,536 | |

| Sri Lanka | 672,809 | 16,907 | |

| Kuwait | 667,290 | 2,570 | |

| Dominican Republic | 661,103 | 4,384 | |

| Moldova | 650,609 | 12,281 | |

| Myanmar | 643,215 | 19,494 | |

| Estonia | 612,467 | 2,998 | |

| Venezuela | 552,695 | 5,856 | |

| Egypt | 516,023 | 24,830 | |

| Qatar | 514,524 | 690 | |

| Libya | 507,269 | 6,437 | |

| Ethiopia | 501,239 | 7,574 | |

| Réunion | 494,595 | 921 | |

| Honduras | 472,909 | 11,114 | |

| Armenia | 453,016 | 8,778 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 403,960 | 16,402 | |

| Oman | 399,449 | 4,628 | |

| Luxembourg | 396,017 | 1,000 | |

| North Macedonia | 352,043 | 9,990 | |

| Zambia | 349,892 | 4,078 | |

| Brunei | 349,279 | 181 | |

| Kenya | 344,109 | 5,689 | |

| Albania | 337,195 | 3,608 | |

| Botswana | 330,696 | 2,801 | |

| Mauritius | 329,121 | 1,074 | |

| Kosovo | 274,279 | 3,212 | |

| Algeria | 272,173 | 6,881 | |

| Nigeria | 267,189 | 3,155 | |

| Zimbabwe | 266,396 | 5,740 | |

| Montenegro | 251,280 | 2,654 | |

| Afghanistan | 235,214 | 7,998 | |

| Mozambique | 233,845 | 2,252 | |

| Martinique | 230,354 | 1,104 | |

| Laos | 219,060 | 671 | |

| Iceland | 210,675 | 186 | |

| Guadeloupe | 203,235 | 1,021 | |

| El Salvador | 201,960 | 4,230 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 191,496 | 4,390 | |

| Maldives | 186,694 | 316 | |

| Uzbekistan | 175,081 | 1,016 | |

| Namibia | 172,556 | 4,110 | |

| Ghana | 172,210 | 1,462 | |

| Uganda | 172,159 | 3,632 | |

| Jamaica | 157,326 | 3,618 | |

| Cambodia | 139,325 | 3,056 | |

| Rwanda | 133,266 | 1,468 | |

| Cameroon | 125,279 | 1,974 | |

| Malta | 123,136 | 925 | |

| Barbados | 108,835 | 593 | |

| Angola | 107,482 | 1,937 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 100,976 | 1,474 | |

| French Guiana | 98,041 | 413 | |

| Senegal | 89,312 | 1,972 | |

| Malawi | 89,168 | 2,686 | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 88,953 | 1,024 | |

| Ivory Coast | 88,448 | 835 | |

| Suriname | 82,503 | 1,406 | |

| New Caledonia | 80,203 | 314 | |

| French Polynesia | 79,451 | 650 | |

| Eswatini | 75,356 | 1,427 | |

| Guyana | 74,491 | 1,302 | |

| Belize | 71,430 | 688 | |

| Fiji | 69,047 | 885 | |

| Madagascar | 68,575 | 1,428 | |

| Jersey | 66,391 | 161 | |

| Cabo Verde | 64,474 | 417 | |

| Sudan | 63,993 | 5,046 | |

| Mauritania | 63,876 | 997 | |

| Bhutan | 62,697 | 21 | |

| Syria | 57,423 | 3,163 | |

| Burundi | 54,569 | 15 | |

| Guam | 52,287 | 419 | |

| Seychelles | 51,892 | 172 | |

| Gabon | 49,056 | 307 | |

| Andorra | 48,015 | 159 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 46,864 | 670 | |

| Curaçao | 45,883 | 305 | |

| Aruba | 44,224 | 292 | |

| Tanzania | 43,263 | 846 | |

| Mayotte | 42,027 | 187 | |

| Togo | 39,533 | 290 | |

| Bahamas | 39,127 | 849 | |

| Guinea | 38,582 | 468 | |

| Isle of Man | 38,008 | 116 | |

| Lesotho | 36,138 | 709 | |

| Guernsey | 35,326 | 67 | |

| Faroe Islands | 34,658 | 28 | |

| Haiti | 34,556 | 860 | |

| Mali | 33,171 | 743 | |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 31,765 | 65 | |

| Cayman Islands | 31,472 | 37 | |

| Saint Lucia | 30,288 | 410 | |

| Benin | 28,036 | 163 | |

| Somalia | 27,334 | 1,361 | |

| Solomon Islands | 25,954 | 199 | |

| United States Virgin Islands | 25,389 | 132 | |

| San Marino | 25,292 | 126 | |

| Republic of the Congo | 25,234 | 389 | |

| Timor-Leste | 23,460 | 138 | |

| Burkina Faso | 22,146 | 400 | |

| Liechtenstein | 21,605 | 89 | |

| Gibraltar | 20,550 | 113 | |

| Grenada | 19,693 | 238 | |

| Bermuda | 18,860 | 165 | |

| South Sudan | 18,847 | 147 | |

| Tajikistan | 17,786 | 125 | |

| Monaco | 17,181 | 67 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 17,130 | 183 | |

| Samoa | 17,057 | 31 | |

| Tonga | 16,992 | 13 | |

| Marshall Islands | 16,297 | 17 | |

| Nicaragua | 16,194 | 245 | |

| Dominica | 16,047 | 74 | |

| Djibouti | 15,690 | 189 | |

| Central African Republic | 15,443 | 113 | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 14,985 | 41 | |

| Gambia | 12,627 | 372 | |

| Collectivity of Saint Martin | 12,324 | 46 | |

| Vanuatu | 12,019 | 14 | |

| Greenland | 11,971 | 21 | |

| Yemen | 11,945 | 2,159 | |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 11,922 | 41 | |

| Sint Maarten | 11,051 | 92 | |

| Eritrea | 10,189 | 103 | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 9,674 | 124 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 9,614 | 177 | |

| Niger | 9,528 | 315 | |

| Comoros | 9,109 | 160 | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 9,106 | 146 | |

| American Samoa | 8,359 | 34 | |

| Liberia | 8,090 | 294 | |

| Sierra Leone | 7,985 | 126 | |

| Chad | 7,702 | 194 | |

| British Virgin Islands | 7,628 | 64 | |

| Cook Islands | 7,375 | 2 | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 6,824 | 40 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 6,771 | 80 | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 6,607 | 46 | |

| Palau | 6,372 | 10 | |

| Saint Barthélemy | 5,507 | 5 | |

| Nauru | 5,393 | 1 | |

| Kiribati | 5,085 | 24 | |

| Anguilla | 3,904 | 12 | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 3,760 | 9 | |

| Macau | 3,514 | 121 | |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 3,426 | 2 | |

| Tuvalu | 2,943 | 1 | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | 2,166 | 0 | |

| Falkland Islands | 1,923 | 0 | |

| Montserrat | 1,403 | 8 | |

| Niue | 1,092 | 0 | |

| Tokelau | 80 | 0 | |

| Vatican City | 26 | 0 | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 4 | 0 | |

| Turkmenistan | 0 | 0 | |

| North Korea | 0 | 0 | |

| |||

Health authorities in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, China, reported a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown cause on 31 December 2019,[32] and an investigation was launched in early January 2020.[33] The cases mostly had links to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market and so the virus is thought to have a zoonotic origin.[34] The virus that caused the outbreak is known as SARS-CoV-2, a newly discovered virus closely related to bat coronaviruses,[35] pangolin coronaviruses[36] and SARS-CoV.[37]

The earliest person with symptoms was traced back to 1 December 2019, someone who did not have connections with the later cluster linked to the wet market.[38][39] Of the early cluster of cases reported in December 2019, two-thirds were found to have a link with the market.[1][40][41] On 14 March 2020, an unverified report from the South China Morning Post said that a 55-year-old from Hubei province could have been the first person who contracted the disease, on 17 November.[42][43]

On 26 February 2020, the WHO reported that, as new cases reportedly dropped in China but suddenly increased in Italy, Iran, and South Korea, the number of new cases outside China had exceeded the number of new cases in China for the first time.[44] There may be substantial underreporting of cases, particularly those with milder symptoms.[45][46] By 26 February, relatively few cases have been reported among youth, with those 19 and under making up 2.4% of cases worldwide.[9][47]

Government sources in Germany and the UK estimate that 60–70% of the population will need to become infected before effective herd immunity can be achieved.[48][49][50]

Deaths

The time from development of symptoms to death has been between 6 and 41 days, with the most common being 14 days.[9] By 21 March more than 11,400 deaths had been attributed to COVID-19.[51] Most of those who have died were elderly—about 80% of deaths were in those over 60, and 75% had pre-existing health conditions including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.[52]

The first confirmed death was on 9 January 2020 in Wuhan.[53] The first death outside China occurred on 1 February in the Philippines,[54][55] and the first death outside Asia was in France on 14 February.[56] By 28 February, outside mainland China, more than a dozen deaths each were recorded in Iran, South Korea, and Italy.[57][58][59] By 13 March, over 40 countries and territories had reported deaths, on every continent except Antarctica.[60]

The case-fatality rate (CFR) is the proportion of persons with a particular condition (cases) who die from that condition.[61] During an epidemic, the death rate can be affected by quality of healthcare, general health and age profile of the population; while the CFR calculation needs to be adjusted to allow for possible under- or over-reporting of cases, and for the time lapse between infection and death.[62][63] Estimates of the mortality rate by the World Health Organization are 3 to 4% as of 6 March 2020.[64] Other estimates of the CFR vary from 1.4%[65] to 2.3%.[66]

Diagrams

-

Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 per million people, 20 March 2020[67]

-

Total confirmed deaths due to COVID-19 per million people, 20 March 2020[68]

-

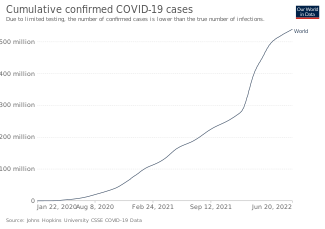

Growth in total confirmed cases

-

Epidemic curve of COVID-19 by date of report

-

Semi-log plot of cumulative incidence of confirmed cases and deaths in China and the rest of the world (ROW)[69][70]

-

Semi-log plot of cases in some countries with high growth rates (post-China) with doubling times and three-day projections based on the exponential growth rates

Signs and symptoms

| Symptom[71] | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Fever | 87.9% |

| Dry cough | 67.7% |

| Fatigue | 38.1% |

| Sputum production | 33.4% |

| Anosmia (loss of smell)[72] | 30-66% |

| Shortness of breath | 18.6% |

| Muscle pain or joint pain | 14.8% |

| Sore throat | 13.9% |

| Headache | 13.6% |

| Chills | 11.4% |

| Nausea or vomiting | 5.0% |

| Nasal congestion | 4.8% |

| Diarrhoea | 3.7% |

| Haemoptysis | 0.9% |

| Conjunctival congestion | 0.8% |

Symptoms of COVID-19 are non-specific and those infected may either be asymptomatic or develop flu-like symptoms such as fever, cough, fatigue, shortness of breath, or muscle pain. The typical signs and symptoms and their prevalence are shown in the corresponding table.[71] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists emergency symptoms including difficulty breathing, persistent chest pain or pressure, sudden confusion, difficulty waking, and bluish face or lips; immediate medical attention is advised if these symptoms are present.[73]

Further development of the disease can lead to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, septic shock and death. Some of those infected may be asymptomatic, returning test results that confirm infection but show no clinical symptoms, so researchers have issued advice that those with close contact to confirmed infected people should be closely monitored and examined to rule out infection.[1][74][75][76] Chinese estimates of the asymptomatic ratio range from few to 44%.[77]

The usual incubation period (the time between infection and symptom onset) ranges from one to fourteen days; it is most commonly five days.[78][79] In one case, it may have had an incubation period of 27 days.[80]

Cause

Transmission

The primary mode of transmission is via respiratory droplets that people exhale or cough.[81] This is thought to occur when people are in close contact, often during coughing or sneezing.[82][83] The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) concur that it seems to spread via these droplets, but "[t]here is not enough epidemiological information at this time [23 March] to determine how easily and sustainably this virus spreads between people."[84] The stability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the air and on various surfaces is believed to be comparable to that of other coronaviruses.[85][86][87] A single study of how long SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) remains infectious on various surfaces, "show[s] that when the virus is carried by the droplets released when someone coughs or sneezes, it remains viable, or able to still infect people, in aerosols for at least three hours."[88]

They also tested SARS-CoV-2 on plastic, stainless steel, copper, and cardboard, and found that although SARS-CoV-2 decayed exponentially over time in all five environments they tested, the virus was viable for infection for up to three days on plastic and stainless steel, for one day on cardboard, and for up to four hours on copper.[89][90][91]

A survey of research on the inactivation of other coronaviruses using various biocidal agents suggests that disinfecting surfaces contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 may also be achieved using similar solutions (within one minute of exposure on a stainless steel surface), including 62–71% ethanol, 50–100% isopropanol, 0.1% sodium hypochlorite, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, and 0.2–7.5% povidone-iodine; benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine gluconate are less effective.[85]

The WHO has stated that the risk of spread from someone without symptoms is "very low". However, if someone has early symptoms and a mild cough, there is a risk of transmission.[92] An analysis of infections in Singapore and Tianjin, China revealed that coronavirus infections may be spread by people who have recently caught the virus and have not yet begun to show symptoms, unlike other coronaviruses such as SARS.[93][94]

Estimates of the basic reproduction number (the average number of people an infected person is likely to infect) range from 2.13[95] to 4.82.[96][97] This is similar to the measure typical of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV).[98]

Virology

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, first isolated from three people with pneumonia connected to the cluster of acute respiratory illness cases in Wuhan.[37] All features of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus occur in related coronaviruses in nature.[99]

SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to the original SARS-CoV.[100] It is thought to have a zoonotic origin. Genetic analysis has revealed that the coronavirus genetically clusters with the genus Betacoronavirus, in subgenus Sarbecovirus (lineage B) together with two bat-derived strains. It is 96% identical at the whole genome level to other bat coronavirus samples (BatCov RaTG13).[71][101] In February 2020, Chinese researchers found that there is only one amino acid difference in certain parts of the genome sequences between the viruses from pangolins and those from humans, however, whole genome comparison to date found at most 92% of genetic material shared between pangolin coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2, which is insufficient to prove pangolins to be the intermediate host.[102]

Diagnosis

Infection by the virus can be provisionally diagnosed on the basis of symptoms, though confirmation is ultimately by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) of infected secretions (71% sensitivity) and CT imaging (98% sensitivity).[103]

Viral testing

The WHO has published several RNA testing protocols for SARS-CoV-2, with the first issued on 17 January.[104][105][106][107] Testing uses real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).[108] The test can be done on respiratory or blood samples.[109] Results are generally available within a few hours to days.[110][111]

A person is considered at risk if they have travelled to an area with ongoing community transmission within the previous 14 days, or have had close contact with an infected person. Common key indicators include fever, coughing and shortness of breath. Other possible indicators include fatigue, myalgia, anorexia, sputum production and sore throat.[112]

Imaging

Characteristic imaging features on radiographs and computed tomography have been described in a limited case series.[113] The Italian Radiological Society is compiling an international online database of imaging findings for confirmed cases.[114] Due to overlap with other infections such as adenovirus, imaging without confirmation by PCR is of limited use in identifying COVID-19.[113] A larger[clarification needed] comparing chest CT results to PCR has suggested that though imaging is less specific for the infection, it is significantly faster and more sensitive, suggesting that it may be considered as a screening tool in epidemic areas.[115]

Prevention

Strategies for preventing transmission of the disease include overall good personal hygiene, hand washing, avoiding touching the eyes, nose or mouth with unwashed hands, coughing/sneezing into a tissue and putting the tissue directly into a dustbin. Those who may already have the infection have been advised to wear a surgical mask in public.[116][117][118] Social distancing measures are also recommended to prevent transmission.[119][120]

Many governments have restricted or advised against all non-essential travel to and from countries and areas affected by the outbreak.[121] However, the virus has reached the stage of community spread in large parts of the world. This means that the virus is spreading within communities whose members have not travelled to areas with widespread transmission.[citation needed]

Health care providers taking care of someone who may be infected are recommended to use standard precautions, contact precautions and airborne precautions with eye protection.[122]

Contact tracing is an important method for health authorities to determine the source of an infection and to prevent further transmission.[123] Misconceptions are circulating about how to prevent infection, for example: rinsing the nose and gargling with mouthwash are not effective.[124] As of 13 March 2020, there is no COVID-19 vaccine, though a number of organizations are working to develop one.[125]

Hand washing

Hand washing is recommended to prevent the spread of the disease. The CDC recommends that people wash hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after going to the toilet or when hands are visibly dirty; before eating; and after blowing one's nose, coughing, or sneezing. It further recommended using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol by volume when soap and water are not readily available.[116] The WHO advises people to avoid touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[117][126]

Respiratory hygiene

Health organizations recommended that people cover their mouth and nose with a bent elbow or a tissue when coughing or sneezing (the tissue should then be disposed of immediately).[117][127] Surgical masks are recommended for those who may be infected,[128][129][130] as wearing a mask can limit the volume and travel distance of expiratory droplets dispersed when talking, sneezing and coughing.[131] The WHO has issued instructions on when and how to use masks.[132]

Masks have also been recommended for use by those taking care of someone who may have the disease.[130] WHO has recommended the wearing of masks by healthy people only if they are at high risk, such as those who are caring for a person with COVID-19, although masks may help people avoid touching their faces.[130]

China has specifically recommended the use of disposable medical masks by healthy members of the public.[133][69][131][134] Hong Kong recommends wearing a surgical mask when taking public transport or staying in crowded places.[135] Thailand's health officials are encouraging people to make face masks at home out of cloth and wash them daily.[136] The Czech Republic banned going out in public without wearing a mask or covering one's nose and mouth.[137] Face masks have also been widely used by healthy people in Taiwan,[138][139] Japan,[140] South Korea,[141] Malaysia,[142] Singapore,[143][144] and Hong Kong.[145]

Physical distancing

Physical distancing (also commonly referred to as social distancing) includes infection control actions intended to slow the spread of disease by minimizing close contact between individuals. Methods include quarantines; travel restrictions; and the closing of schools, workplaces, stadiums, theatres, or shopping centres. Individuals may apply physical distancing methods by staying at home, limiting travel, avoiding crowded areas, using no-contact greetings, and physically distancing themselves from others.[146][147] Many governments are now mandating or recommending physical distancing in regions affected by the outbreak.[148][149] Allowed gathering size was swiftly reducing from 250 people (if there was no known COVID-19 spread in a region) to 50 people, and later to 10 people.[150] On 22 March 2020, Germany banned public gatherings of more than two people.[151]

Older adults and those with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, respiratory disease, hypertension, and compromised immune systems face increased risk of serious illness and complications and have been advised by the US CDC to stay home as much as possible in areas of community outbreak.[152][153]

In late-March 2020, the WHO and other health bodies began to replace use of the term "social distancing" with "physical distancing", in order to clarify the specific goal of reducing close physical contact. The use of the term "social distancing" had led to implications that people should engage in complete social isolation, rather than encouraging them to stay in contact with others via alternative means.[154][155]

Self-isolation

Self-isolation at home has been recommended for those diagnosed with COVID-19 and those who suspect they have been infected. Health agencies have issued detailed instructions for proper self-isolation.[156][157]

Additionally, many governments have mandated or recommended self-quarantine for entire populations living in affected areas.[158][159] The strongest self-quarantine instructions have been issued to those in high risk groups. Those who may have been exposed to someone with COVID-19 and those who have recently travelled to a country with widespread transmission have been advised to self-quarantine for 14 days from the time of last possible exposure.[6][8][160]

Management

Outbreak

There are a number of strategies in the control of an outbreak: containment, mitigation, and suppression. Containment is undertaken in the early stages of the outbreak and aims to trace and isolate those infected as well as other measures of infection control and vaccinations to stop the disease from spreading to the rest of the population. When it is no longer possible to contain the spread of the disease, efforts then move to the mitigation stage, when measures are taken to slow the spread and mitigate its effects on the health care system and society. A combination of both containment and mitigation measures may be undertaken at the same time.[163] Suppression requires more extreme measures so as to reverse the pandemic by reducing the basic reproduction number to less than 1.[164]

Part of managing an infectious disease outbreak is trying to decrease the epidemic peak, known as flattening the epidemic curve.[161] This decreases the risk of health services being overwhelmed and provides more time for vaccines and treatments to be developed.[161] Non-pharmaceutical interventions that may manage the outbreak include personal preventive measures, such as hand hygiene, wearing face-masks and self-quarantine; community measures aimed at physical distancing such as closing schools and cancelling mass gathering events; community engagement to encourage acceptance and participation in such interventions; as well as environmental measures such surface cleaning.[165]

More drastic actions aim at suppressing the outbreak were taken in China once the severity of the outbreak became apparent, such as quarantining entire cities affecting 60 million individuals in Hubei, and strict travel bans.[166] Other countries adopted a variety of measures aimed at limiting the spread of the virus. For example, South Korea introduced mass screening, localized quarantines, and issuing alerts on the movements of affected individuals. Singapore provided financial support for those infected who quarantine themselves and imposed large fines for those who failed to do so. Taiwan increased face-mask production and penalized hoarding of medical supplies.[167] Some countries require people to report flu-like symptoms to their doctor, especially if they have visited mainland China.[168]

Simulations for Great Britain and the US show that mitigation (slowing but not stopping epidemic spread), as well as suppression (reversing epidemic growth), has major challenges. Optimal mitigation policies might reduce peak healthcare demand by 2/3 and deaths by half, still resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems being overwhelmed. Suppression can be preferred but need to be maintained until a vaccine becomes available (at least 18 months later) as transmission quickly rebounds when relaxed, while long-term intervention causes social and economic costs.[164]

Illness

There are no specific antiviral medications approved for COVID-19, but development efforts are underway, including testing of existing medications. Attempts to relieve the symptoms may include taking regular (over-the-counter) cold medications,[169] drinking fluids, and resting.[116] Depending on the severity, oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids and breathing support may be required.[170] The use of steroids may worsen outcomes.[171] Several compounds, which were previously approved for treatment of other viral diseases, are being investigated.[172]

History

Patient zero is the term used to describe the first-ever case of a disease.[173] There have been various theories as to where the "patient zero" case may have originated.[173] The first known case of the novel coronavirus was traced back to 1 December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei, China.[38] A later unconfirmed claim, citing Chinese government documents, suggests that the first victim was a 55-year-old man who fell ill on 17 November 2019.[174][under discussion] Within the next month, the number of coronavirus cases in Hubei gradually increased to a couple of hundred, before rapidly increasing in January 2020. On 31 December 2019, the virus had caused enough cases of unknown pneumonia to be reported to health authorities in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province,[32] to trigger an investigation.[33] These were mostly linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which also sold live animals; thus the virus is thought to have a zoonotic origin.[34]

During the early stages, the number of cases doubled approximately every seven and a half days.[175] In early and mid-January 2020, the virus spread to other Chinese provinces, helped by the Chinese New Year migration, with Wuhan being a transport hub and major rail interchange, and infections quickly spread throughout the country.[71] On 20 January, China reported nearly 140 new cases in one day, including two people in Beijing and one in Shenzhen.[176] Later official data shows that 6,174 people had already developed symptoms by 20 January 2020.[177]

On 30 January, the WHO declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[178] On 24 February, WHO director Tedros Adhanom warned that the virus could become a global pandemic because of the increasing number of cases outside China.[179]

On 11 March, the WHO officially declared the coronavirus outbreak to be a pandemic, following a period of sustained community-level transmission in multiple regions of the world.[5] On 13 March, the WHO declared Europe to be the new centre of the pandemic after the rate of new European cases surpassed that of regions of the world apart from China.[180] By 16 March 2020, the total number of cases reported around the world outside China had exceeded that of mainland China.[181] On 19 March 2020, China reported no new domestic cases (excluding cases re-imported from abroad) for the first time since the outbreak, while the total number of deaths in Italy surpassed that of China.[182]

As of 23 March 2020[update], over 368,000 cases have been reported worldwide; more than 16,300 people have died and over 101,000 have recovered.[2][3]

Domestic responses

More than 170 territories have had at least one case.[183] Due to the pandemic in Europe, multiple countries in the Schengen Area have restricted free movement and set up border controls.[184] National reactions have included containment measures such as quarantines and curfews.[185] As of 21 March, more than 250 million people are in lockdown in Europe,[186] and more than 100 million people are in lockdown in the United States.[187]

China

The first person known to have fallen ill due to the new virus was traced back to 1 December 2019 in Wuhan.[38] Doctor Zhang Jixian observed a cluster of unknown pneumonia on 26 December, and her hospital informed Wuhan Jianghan CDC on 27 December.[188] A public notice on the outbreak was released by Wuhan Municipal Health Commission on 31 December.[189] WHO was informed of the outbreak on the same day.[32] At the same time these notifications were happening, doctors in Wuhan were being threatened by policy for sharing information about the outbreak.[190] Chinese National Health Commission initially said that they had no "clear evidence" of human-to-human transmissions.[191]

The Chinese Communist Party launched a radical campaign described by the Party general secretary Xi Jinping as a "people's war" to contain the spread of the virus.[194] In what has been described as "the largest quarantine in human history",[195] a quarantine was announced on 23 January stopping travel in and out of Wuhan,[196] which was extended to a total of 15 cities in Hubei, affecting a total of about 57 million people.[197] Private vehicle use was banned in the city.[198] Chinese New Year (25 January) celebrations were cancelled in many places.[199] The authorities also announced the construction of a temporary hospital, Huoshenshan Hospital, which was completed in 10 days, and 14 temporary hospitals were constructed in China in total.[200]

On 26 January, the Communist Party and the government instituted further measures to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, including health declarations for travellers and changes to national holidays.[201] The leading group decided to extend the Spring Festival holiday to contain the outbreak.[202] Universities and schools around the country were also closed.[203][204][205] The regions of Hong Kong and Macau instituted several measures, particularly in regard to schools and universities.[206] Remote working measures were instituted in several Chinese regions.[207] Travel restrictions were enacted.[207][208] Other provinces and cities outside Hubei imposed travel restrictions. Public transport was modified,[209][207] and museums throughout China were temporarily closed.[210][211] Control of movement of people was applied in many cities, and it has been estimated that over half of China's population, around 760 million people, faced some forms of outdoor restriction.[212]

After the outbreak entered its global phase in March, many Chinese students studying in Europe and the United States have returned home as the domestic daily new cases in China declined. Chinese authorities have taken strict measures to prevent the virus from "importing" from other countries. For example, Beijing has imposed a 14-day mandatory quarantine for all international travellers entering the city.[213]

The early response by the Wuhan authorities was criticized as prioritizing control of information that might be unfavourable for local officials over public safety, and the Chinese government was also criticized for cover-ups and downplaying the initial discovery and severity of the outbreak.[214] In early January 2020, Wuhan police summoned and "admonished" several doctors—including Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital—for "spreading rumours" likening the disease to SARS.[215] Li later died because of the virus.[216] Later in March, Wuhan police apologized to Li's family after National Supervisory Commission admitted the conduct of local officials was inadequate and acknowledged the whistleblower's effort on raising public awareness.[217][218] Observers have also blamed the institutional censorship that left the citizens and senior officials with inaccurate information on the outbreak and "contributed to a prolonged period of inaction that allowed the virus to spread".[219] Some experts doubted the accuracy of the number of cases reported by the Chinese government, which repeatedly changed how it counted coronavirus cases, while others say it wasn’t likely a deliberate attempt to manipulate the data.[220][221][222] The Chinese government has also been accused of rejecting help from the US CDC and the WHO.[223]

Although criticisms have been levelled at the aggressive response of China to control the outbreak,[224] China's actions have also been praised by some foreign leaders such as U.S. President Donald Trump, and Russian president Vladimir Putin.[225][226] Trump later reversed himself, saying "I wish they could have told us earlier about what was going on inside," adding that China "was very secretive, and that's unfortunate".[227] The director of WHO Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus congratulated Chinese government "for the extraordinary measures it has taken to contain the outbreak",[228] and a later WHO report described China's response as "perhaps the most ambitious, agile and aggressive disease containment effort in history".[229] According to a media report on 16 March, the economy in China was very hard hit in the first two months of 2020 due to the measures taken by the government to curtail virus spread, and retail sales plunged 20.5%.[230] Per media reports, on 23 March the country of China has gone five days with only one case (not imported).[231]

South Korea

COVID-19 was confirmed to have spread to South Korea on 20 January 2020 from China. There was a large increase in cases on 20 February,[232] potentially attributable to a gathering in Daegu of a new religious movement known as the Shincheonji Church of Jesus.[232][233][234]

Shincheonji devotees visiting Daegu from Wuhan were suspected to be the origin of the outbreak.[235][236] As of 22 February, among 9,336 followers of the church, 1,261 or about 13% reported symptoms.[237]

South Korea declared the highest level of alert on 23 February 2020.[238] On 28 February, over 2,000 confirmed cases were reported in Korea,[239] rising to 3,150 on 29 February.[240] All South Korean military bases were on quarantine after tests confirmed that three soldiers were positive for the virus.[235] Airline schedules were also affected and therefore they were changed.[241][242]

South Korea introduced what was considered the largest and best-organised program in the world to screen the population for the virus, and isolate any infected people as well as tracing and quarantining those who contacted them.[243][244] Screening methods included a drive-thru testing for the virus with the results available the next day.[245] It is considered to be a success in controlling the outbreak despite not quarantining entire cities.[243][246]

The South Korean society was initially polarised with President Moon Jae-in's response to the crisis. Many Koreans signed petitions either calling for the impeachment of Moon over what they claimed is the government's mishandling of the outbreak, or praising his response.[247] On 23 March, it was reported that South Korea had the lowest one-day case total in four weeks.The country of South Korea's different approach to the outbreak includes having 20,000 people tested every day for coronavirus.[248]

Iran

Iran reported its first confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections on 19 February in Qom, where, according to the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, two people had died later that day.[249][250] Early measures announced by the government included the cancellation of concerts and other cultural events,[251] sporting events,[252] and Friday prayers,[253] universities, higher education institutions and schools.[254] Iran allocated five trillion rials to combat the virus.[255] President Hassan Rouhani said on 26 February 2020 that there were no plans to quarantine areas affected by the outbreak, and only individuals would be quarantined.[256] Plans to limit travel between cities were announced in March.[257] Shia shrines in Qom remained open to pilgrims until 16 March 2020.[258][259]

Iran became a centre of the spread of the virus after China.[260][261] Amidst claims of a cover-up of the extent of the outbreak in the country,[262] over ten countries had traced their cases back to Iran by 28 February, indicating that the extent of the outbreak may be more severe than the 388 cases reported by the Iranian government by that date.[261][263] The Iranian Parliament was shut down, with 23 of its 290 members reported to have had tested positive for the virus on 3 March.[264] A number of senior government officials, as well as two members of the Parliament, have died from the disease.[265] On 15 March, the Iranian government reported 100 deaths in a single day, the most recorded since the outbreak began.[266] Per media reports on 23 March Iran has 50 new cases every hour and one new death every ten minutes due to coronavirus. Even so, some sources like Radio Farda, which is U.S. backed, says Iran may be under-reporting.[267]

Italy

The outbreak was confirmed to have spread to Italy on 31 January, when two Chinese tourists tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Rome.[268] In response, the Italian government suspended all flights to and from China and declared a state of emergency.[269] On 31 January, the Italian Council of Ministers appointed Angelo Borrelli, head of the Civil Protection, as Special Commissioner for the COVID-19 Emergency.[270][271] An unassociated cluster of COVID-19 cases was later further detected starting with 16 confirmed cases in Lombardy on 21 February.[272]

On 22 February, the Council of Ministers announced a new decree-law to contain the outbreak, including quarantining more than 50,000 people from 11 different municipalities in northern Italy.[273] Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said "In the outbreak areas, entry and exit will not be provided. Suspension of work activities and sports events has already been ordered in those areas."[274][275]

On 4 March, the Italian government ordered the full closure of all schools and universities nationwide as Italy reached 100 deaths. All major sporting events, including Serie A football matches, will be held behind closed doors until April.[276] On 9 March, all sport was suspended completely for at least one month.[277] On 11 March, Prime Minister Conte ordered stoppage of nearly all commercial activity except supermarkets and pharmacies.[278][279]

On 6 March, the Italian College of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) published medical ethics recommendations regarding triage protocols that might be employed.[280][281][282]

On 19 March, Italy overtook China as the country with the most coronavirus-related deaths in the world after reporting 3,405 fatalities from the pandemic.[283][284] As of 23 March 2020[update], there were 63,928 confirmed cases, 6,078 deaths and 7,432 recoveries in Italy.[285][286] On the same date it was reported that Russia had sent nine military planes with medical equipment to the country of Italy.[287]

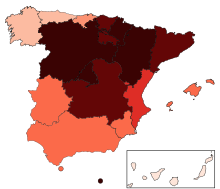

Spain

The COVID-19 pandemic in Spain has resulted in 13,980,340[31] confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 121,852[31] deaths.

The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Spain on 31 January 2020, when a German tourist tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in La Gomera, Canary Islands.[288] Post-hoc genetic analysis has shown that at least 15 strains of the virus had been imported, and community transmission began by mid-February.[289] By 13 March, cases had been confirmed in all 50 provinces of the country.

A partially unconstitutional lockdown was imposed on 14 March 2020.[290][291] On 29 March, it was announced that, beginning the following day, all non-essential workers were ordered to remain at home for the next 14 days.[292] By late March, the Community of Madrid has recorded the most cases and deaths in the country. Medical professionals and those who live in retirement homes have experienced especially high infection rates.[293] On 25 March, the official death toll in Spain surpassed that of mainland China.[294] On 2 April, 950 people died of the virus in a 24-hour period—at the time, the most by any country in a single day.[295] On 17 May, the daily death toll announced by the Spanish government fell below 100 for the first time,[296] and 1 June was the first day without deaths by COVID-19.[297] The state of alarm ended on 21 June.[298] However, the number of cases increased again in July in a number of cities including Barcelona, Zaragoza and Madrid, which led to reimposition of some restrictions but no national lockdown.[299][300][301][302]

Studies have suggested that the number of infections and deaths may have been underestimated due to lack of testing and reporting, and many people with only mild or no symptoms were not tested.[303][304] Reports in May suggested that, based on a sample of more than 63,000 people, the number of infections may be ten times higher than the number of confirmed cases by that date, and Madrid and several provinces of Castilla–La Mancha and Castile and León were the most affected areas with a percentage of infection greater than 10%.[305][306] There may also be as many as 15,815 more deaths according to the Spanish Ministry of Health monitoring system on daily excess mortality (Sistema de Monitorización de la Mortalidad Diaria – MoMo).[307] On 6 July 2020, the results of a Government of Spain nationwide seroprevalence study showed that about two million people, or 5.2% of the population, could have been infected during the pandemic.[308][309] Spain was the second country in Europe (behind Russia) to record half a million cases.[310] On 21 October, Spain passed 1 million COVID-19 cases, with 1,005,295 infections and 34,366 deaths reported, a third of which occurred in Madrid.[311]

As of September 2021, Spain is one of the countries with the highest percentage of its population vaccinated (76% fully vaccinated and 79% with the first dose),[312] while also being one of the countries more in favor of vaccines against COVID-19 (nearly 94% of its population is already vaccinated or wants to be).[313]

As of 4 February 2023, a total of 112,304,453 vaccine doses have been administered.[314]On 23 March, it was reported that some 4,000 health workers are infected with the virus in Spain.The country is currently the second most affected by the coronavirus outbreak in all Europe.[315]

United States

The first known case in the United States of COVID-19 was confirmed in the Pacific Northwest state of Washington on 20 January 2020, in a man who had returned from Wuhan on 15 January.[317] The White House Coronavirus Task Force was established on 29 January.[318] On 31 January, the Trump administration declared a public health emergency,[319] and placed travel restrictions on entry for travellers from China.[320]

After the first death in the United States was reported in Washington state on 29 February,[321] its governor, Jay Inslee, declared a state of emergency,[322] an action that was followed by other states.[323][324][325] Schools in the Seattle area cancelled classes on 3 March,[326] and by mid-March, schools across the country were closing and most of the country's students were out of school.[327]

On 6 March, president Donald Trump signed the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, which provided $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to respond to the outbreak.[328] Corporations imposed employee travel restrictions, cancelled conferences,[329] and encouraged employees to work from home.[330] Sports events and seasons were cancelled.[24][331]

On 11 March, Trump announced travel restrictions for most of Europe (excluding the United Kingdom) for 30 days, effective 13 March,[332] and on 14 March, he expanded the restrictions to include the United Kingdom and Ireland.[333] On 13 March, he declared a national emergency, which made federal funds available to respond to the crisis.[334] Beginning on 15 March, many businesses closed or reduced hours throughout the U.S. as a method to try to combat the virus.[335]

As of 23 March 2020[update], the epidemic was present in all 50 states, plus the District of Columbia. The number of confirmed cases in the U.S. rose to 41,525, with 501 deaths.[336][2][3] On 23 March, it was reported that New York city had 10,700 cases of the coronavirus, an amount that is greater than the country of South Korea currently.[337]

The White House has been criticized for downplaying the threat and controlling the messaging by directing health officials and scientists to coordinate public statements and publications related to the virus with the office of Vice President Mike Pence [338][339][340], yet an ABC/Ipsos poll released March 20, 2020 reports that 55% of respondents approve of President Trump's management of the public health crisis.

United Kingdom

The UK response to the virus first emerged as one of the most relaxed of the affected countries, and until 18 March 2020, the British government did not impose any form of social distancing or mass quarantine measures on its citizens.[341][342] On 15 March, it was reported that the UK government would no longer test individuals self-isolating with mild symptoms of coronavirus, however, it would test individuals seeking hospital treatment for the virus and those in long-term care facilities.[343] On 16 March, Prime Minister Boris Johnson made an announcement advising against all non-essential travel and social contact, to include working from home where possible and avoiding venues such as pubs, restaurants and theatres.[344][345] The government imposed restrictions on 18 March which limited school attendance to only the children of those in selected professions, namely NHS employees, police and those vital to food supply.[346]

On 20 March, the government announced that all leisure establishments (pubs, gyms etc.) were to close as soon as possible,[347] and promised to pay up to 80% of workers' wages, to a limit of £2,500 per month, to prevent unemployment in the crisis.[348] The government has received criticism for the perceived lack of pace and intensity in its response to concerns faced by the public.[349][350][351] Only 23% of British adults were strictly following the government's coronavirus advice, a poll has found.[352]

On 22 March, the government asked those in the country with certain health conditions (an estimated 1.5 million) to self-isolate for 12 weeks. Identification and notification was to be coordinated by the National Health Service, with deliveries of medication, food, and household essentials by pharmacists and local governments, and at least initially paid for by the national government.[353] On 23 March it was reported that the U.K. would go into lockdown in the next 24 hours due to the coronavirus outbreak, the report goes on to say some individuals are not observing the 2-metre rule.[354]

International responses

An analysis of air travel patterns was used to map out and predict patterns of spread and was published in The Journal of Travel Medicine in mid-January 2020. Based on information from the International Air Transport Association (2018), Bangkok, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Taipei had the largest volume of travellers from Wuhan. Dubai, Sydney and Melbourne were also reported as popular destinations for people travelling from Wuhan. Bali was reported as least able in terms of preparedness, while cities in Australia were considered most able.[355][356]

There have been international comments that the 2020 Olympics should be moved from Japan or postponed. On 22 January, the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) announced that it would be moving the matches in the third round of the 2020 AFC Women's Olympic Qualifying Tournament from Wuhan to Nanjing, affecting the women's national team squads from Australia, China PR, Chinese Taipei and Thailand.[357] A few days later, the AFC announced that together with Football Federation Australia they would be moving the matches to Sydney.[358] The Asia-Pacific Olympic boxing qualifiers, which were originally set to be held in Wuhan from 3 to 14 February, were also cancelled and moved to Amman, Jordan to be held between 3 and 11 March.[359][360]

Australia released its Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) on 7 February. It states that much is yet to be discovered about COVID-19, and that Australia will emphasize border control and communication in its response to the pandemic.[361]

Travel restrictions

As a result of the outbreak, many countries and regions including most of the Schengen Area,[362] Armenia,[363] Australia,[364] India,[365] Iraq,[366][367] Indonesia,[368] Kazakhstan,[369] Kuwait,[370] Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, New Zealand, Philippines, Russia,[371] Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan,[372] Vietnam,[373] and the United States[374] have imposed temporary entry bans on Chinese citizens or recent visitors to China, or have ceased issuing visas and reimposed visa requirements on Chinese citizens.[375] Samoa started refusing entry to its own citizens who had previously been to China, attracting widespread condemnation over the legality of the decision.[376][377]

The European Union rejected the idea of suspending the Schengen free travel zone and introducing border controls with Italy,[378][379][380] which has been criticized by some European politicians.[381][382] After some EU member states announced complete closure of their national borders to foreign nationals,[383] the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that "Certain controls may be justified, but general travel bans are not seen as being the most effective by the World Health Organization."[384]

Saudi Arabia temporarily banned foreigners from entering Mecca and Medina, two of Islam's holiest pilgrimage sites, to prevent the spread of coronavirus.[385] The United States suspended travel from the Schengen Area and later the Common Travel Area.[386] Many countries then started closing their borders to virtually all non-citizens or non-residents in rapid succession,[387] including India,[388] Slovakia,[389] Denmark,[390] Poland,[391] Lithuania,[392] Oman[393], United Arab Emirates and Russia.[394][395]

Evacuation of foreign citizens

Owing to the effective quarantine of public transport in Wuhan and Hubei, several countries have planned to evacuate their citizens and diplomatic staff from the area, primarily through chartered flights of the home nation that have been provided clearance by Chinese authorities. Canada, the United States, Japan, India, France, Australia, Sri Lanka, Germany and Thailand were among the first to plan the evacuation of their citizens.[396] Pakistan has said that it will not be evacuating any citizens from China.[397] On 7 February, Brazil evacuated 34 Brazilians or family members in addition to four Poles, a Chinese person and an Indian citizen. The citizens of Poland, China and India deplaned in Poland, where the Brazilian plane made a stopover before following its route to Brazil. Brazilian citizens who went to Wuhan were quarantined at a military base near Brasília.[398][399][400] On the same day, 215 Canadians (176 from the first plane, and 39 from a second plane chartered by the US government) were evacuated from Wuhan to CFB Trenton to be quarantined for two weeks. [citation needed]

On 11 February, another plane of 185 Canadians from Wuhan landed at CFB Trenton. Australian authorities evacuated 277 citizens on 3 and 4 February to the Christmas Island Detention Centre, which had been repurposed as a quarantine facility, where they remained for 14 days.[401][402][403] A New Zealand evacuation flight arrived in Auckland on 5 February; its passengers (including some from Australia and the Pacific) were quarantined at a naval base in Whangaparoa, north of Auckland.[404] The United States announced that it would evacuate Americans aboard the cruise ship Diamond Princess.[405] On 21 February, a plane carrying 129 Canadian passengers who had been evacuated from Diamond Princess landed in Trenton, Ontario.[406] The Indian government has scheduled its air force to evacuate its citizens from Iran.[407]

International aid

On 5 February, the Chinese foreign ministry stated that 21 countries (including Belarus, Pakistan, Trinidad and Tobago, Egypt and Iran) had sent aid to China.[408] The US city of Pittsburgh announced plans to send medical aid to Wuhan, which is its sister city.[409] The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) also announced plans to provide help.[410] Some Chinese students at American universities have joined together to help send aid to virus-stricken parts of China, with a joint group in the greater Chicago area reportedly managing to send 50,000 N95 masks and 1,500 protection suits to hospitals in the Hubei province on 30 January.[411]

The humanitarian aid organization Direct Relief, in coordination with FedEx transportation and logistics support, sent 200,000 face masks along with other personal protective equipment, including gloves and gowns, by emergency airlift to the Wuhan Union Hospital by 30 January.[412] The Gates Foundation stated on 26 January that it would donate US$5 million in emergency funds to support the response in China, along with technical support for front-line responders.[413] On 5 February, Bill and Melinda Gates further announced a US$100 million donation to the WHO to fund vaccine research and treatment efforts along with protecting "at-risk populations in Africa and South Asia".[414]

Japan, in planning a flight to Wuhan to pick up Japanese nationals there, promised that the plane would bring aid supplies that, according to Japanese foreign minister Toshimitsu Motegi, would consist of "masks and protective suits for Chinese people as well as for Japanese nationals".[415] On 26 January, the plane arrived in Wuhan, donating its supply of one million face masks to the city.[416] Among the aid supplies were 20,000 protective suits for medical staff across Hubei donated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.[417]

On 28 January, the city of Mito donated 50,000 masks to its sister city of Chongqing, and on 6 February, the city of Okayama sent 22,000 masks to Luoyang, its sister city. On 10 February, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) of Japan made a symbolic deduction of 5,000 yen from the March salary of every LDP parliamentarian, a total of two million yen, to donate to China; party secretary general Toshihiro Nikai statied that "For Japan, when it sees a virus outbreak in China, it is like seeing a relative or neighbour suffering. Japanese people are willing to help China and hope the outbreak will pass as soon as possible."[418]

Other countries have also announced aid efforts. Malaysia announced a donation of 18 million medical gloves to China.[419] The Philippine Red Cross donated $1.4 million worth of Philippine-made face masks to Wuhan.[420] Turkey dispatched medical equipment,[421] and Germany delivered various medical supplies including 10,000 Hazmat suits.[422] On 19 February, the Singapore Red Cross announced that it would send $2.26 million worth of aid to China, consisting of protective material and training.[423]

In March 2020, China and Russia sent medical supplies and experts to help Italy deal with its coronavirus outbreak.[424][425]Businessman Jack Ma sent 1.1 million testing kits, 6 million face masks and 60,000 protective suits to Addis Ababa for distribution by the African Union [426], as concern grows that poor health infrastructure and high levels of HIV in the region [427], could precipitate severe disruption.

WHO response measures

The WHO has commended the efforts of Chinese authorities in managing and containing the epidemic, with Director-General Tedros Adhanom expressing "confidence in China's approach to controlling the epidemic" and calling for the public to "remain calm".[428] The WHO noted the contrast between the 2003 epidemic, where Chinese authorities were accused of secrecy that impeded prevention and containment efforts, and the current crisis where the central government "has provided regular updates to avoid panic ahead of Lunar New Year holidays".[429]

On 23 January, in reaction to the central authorities' decision to implement a transportation ban in Wuhan, WHO representative Gauden Galea remarked that while it was "certainly not a recommendation the WHO has made", it was also "a very important indication of the commitment to contain the epidemic in the place where it is most concentrated" and called it "unprecedented in public health history".[429]

On 30 January, following confirmation of human-to-human transmission outside China and the increase in the number of cases in other countries, the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the sixth PHEIC since the measure was first invoked during the 2009 swine flu pandemic. Tedros clarified that the PHEIC, in this case, was "not a vote of no confidence in China", but because of the risk of global spread, especially to low- and middle-income countries without robust health systems.[178][430] In response to the implementations of travel restrictions, Tedros stated that "there is no reason for measures that unnecessarily interfere with international travel and trade" and that "WHO doesn't recommend limiting trade and movement."[431]

On 5 February, the WHO appealed to the global community for a $675 million contribution to fund strategic preparedness in low-income countries, citing the urgency to support those countries which "do not have the systems in place to detect people who have contracted the virus, even if it were to emerge". Tedros further made statements declaring that "We are only as strong as our weakest link" and urged the international community to "invest today or pay more later".[432][433]

On 11 February, the WHO in a press conference established COVID-19 as the name of the disease. On the same day, Tedros stated that UN Secretary-General António Guterres had agreed to provide the "power of the entire UN system in the response". A UN Crisis Management Team was activated as a result, allowing co-ordination of the entire United Nations response, which the WHO states will allow them to "focus on the health response while the other agencies can bring their expertise to bear on the wider social, economic and developmental implications of the outbreak".[434]

On 14 February, a WHO-led Joint Mission Team with China was activated to provide international and WHO experts to touch ground in China to assist in the domestic management and evaluate "the severity and the transmissibility of the disease" by hosting workshops and meetings with key national-level institutions to conduct field visits to assess the "impact of response activities at provincial and county levels, including urban and rural settings".[435]

On 25 February, the WHO declared that "the world should do more to prepare for a possible coronavirus pandemic," stating that while it was still too early to call it a pandemic, countries should nonetheless be "in a phase of preparedness".[436] In response to a developing outbreak in Iran, the WHO sent a Joint Mission Team there on the same day to assess the situation.[437]

On 28 February, WHO officials said that the coronavirus threat assessment at the global level would be raised from "high" to "very high", its highest level of alert and risk assessment. Mike Ryan, executive director of WHO's health emergencies program, warned in a statement that "This is a reality check for every government on the planet: Wake up. Get ready. This virus may be on its way and you need to be ready," urging that the right response measures could help the world avoid "the worst of it". Ryan further stated that the current data did not warrant public health officials to declare a global pandemic, saying that such a declaration would mean "we're essentially accepting that every human on the planet will be exposed to that virus."[438]

On 11 March, the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak an official pandemic.[439] The Director-General said that WHO was "deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction".[440]

Impacts

Politics

A number of provincial-level administrators of the Communist Party of China (CPC) were dismissed over their handling of the quarantine efforts in Central China, a sign of discontent with the political establishment's response to the outbreak in those regions. Some experts believe this is likely in a move to protect Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping from people's anger over the coronavirus outbreak.[441]

The Italian government has criticised the European Union's lack of solidarity with coronavirus-affected Italy.[442][443]

The outbreak has prompted The Boston Globe to call for the US to adopt social policies common in other wealthy countries, including universal health care, universal child care, paid family leave, and higher levels of funding for public health.[444]

The Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran has been heavily affected by the virus.[445][446] Iran's President Hassan Rouhani wrote a public letter to world leaders asking for help, saying that his country doesn't have access to international markets due to the United States sanctions against Iran.[447]

Diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea worsened due to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[448] South Korea criticised Japan's "ambiguous and passive quarantine efforts".[449]

Education

As of 20 March, more than 960 million children and other students were affected by temporary or indefinite government-mandated school closures.[22][450][451] Of these, 105 countries shut schools nationwide, affecting students who would normally attend pre-primary to upper-secondary classes, and 15 countries implemented localized closures, affecting an additional 640 million school children and other students.[452]

Even when school closures were temporary, the measures carried high social and economic costs, affecting people across communities, but their impact was more severe for disadvantaged children and their families, causing interrupted learning, compromised nutrition, childcare problems and consequent economic cost to families who could not work.[22][453]

In response to school closures, UNESCO recommended the use of distance learning programs, open educational applications and platforms that schools and teachers can use to reach learners remotely and limit the disruption of education.[452]

Socioeconomics

The coronavirus outbreak has been attributed to several instances of supply shortages, stemming from: globally increased usage of equipment to fight the outbreaks, panic buying and disruption to factory and logistic operations. The United States Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings about shortages to drugs and medical equipment due to increased consumer demand and supplier disruption.[454] Several localities, such as the United States,[455] Italy,[456] and Hong Kong,[457] also witnessed panic buying that led to shelves being cleared of grocery essentials such as food, toilet paper and bottled water, inducing supply shortages.[458] The technology industry in particular has been warning about delays to shipments of electronic goods.[459] According to WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom, the demand for personal protection equipment has risen 100-fold and this demand has led to the increase in prices of up to twenty times the normal price and also induced delays on the supply of medical items for four to six months.[460][461] This has also caused a shortage of personal protective equipment worldwide, with the WHO warning that this will endanger health workers.[462]

In Australia the pandemic has provided a new opportunity for daigou shoppers to sell Australian product into China.[463] This activity has left locals without essential supplies.[464]

As mainland China is a major economy and a manufacturing hub, the viral outbreak has been seen to pose a major destabilizing threat to the global economy. Agathe Demarais of the Economist Intelligence Unit has forecast that markets will remain volatile until a clearer image emerges on potential outcomes. In January 2020, some analysts estimated that the economic fallout of the epidemic on global growth could surpass that of the SARS outbreak.[465] One estimate from an expert at Washington University in St. Louis gave a $300+ billion impact on the world's supply chain that could last up to two years.[466] Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries reportedly "scrambled" after a steep decline in oil prices due to lower demand from China.[467] Global stock markets fell on 24 February due to a significant rise in the number of COVID-19 cases outside mainland China.[468][469] On 27 February, due to mounting worries about the coronavirus outbreak, various US stock indexes including the NASDAQ-100, the S&P 500 Index and the Dow Jones Industrial Average, posted their sharpest falls since 2008, with the Dow falling 1,191 points, the largest one-day drop since the financial crisis of 2007–08.[470] All three indexes ended the week down more than 10%.[471] On 28 February, Scope Ratings GmbH affirmed China's sovereign credit rating, but maintained a Negative Outlook.[472] Stocks plunged again based on coronavirus fears, the largest fall being on 16 March 2020.[473] Many consider an economic recession to be likely.[474][475][476]

Tourism is one of the worst affected sectors due to travel bans, closing of public places including travel attractions, and advise of governments against any travel all over the world. As a consequence, numerous airlines have cancelled flights due to lower demand, including British Airways, China Eastern and Qantas, while British regional airline Flybe collapsed.[477] Several train stations and ferry ports have also been closed.[478] The epidemic coincided with the Chunyun, a major travel season associated with the Chinese New Year holiday. A number of events involving large crowds were cancelled by national and regional governments, including annual New Year festivals, with private companies also independently closing their shops and tourist attractions such as Hong Kong Disneyland and Shanghai Disneyland.[479][480] Many Lunar New Year events and tourist attractions have been closed to prevent mass gatherings, including the Forbidden City in Beijing and traditional temple fairs.[481] In 24 of China's 31 provinces, municipalities and regions, authorities extended the New Year's holiday to 10 February, instructing most workplaces not to re-open until that date.[482][483] These regions represented 80% of the country's GDP and 90% of exports.[483] Hong Kong raised its infectious disease response level to the highest and declared an emergency, closing schools until March and cancelling its New Year celebrations.[484][485]

Despite the high prevalence of coronavirus cases in Northern Italy and the Wuhan region, and the ensuing high demand for food products, both areas have been spared from acute food shortages. Effective measures by China and Italy against the hoarding and illicit trade of critical products have been carried out with success, avoiding acute food shortages that were anticipated in Europe as well as in North America. Northern Italy with its significant agricultural production has not seen a large reduction, but prices may increase according to industry representatives. Empty food shelves were only encountered temporarily, even in Wuhan city, while Chinese government officials released pork reserves to assure sufficient nourishment of the population. Similar laws exist in Italy, that require food producers to keep reserves for such emergencies.[486][487]

Environment

Due to the coronavirus outbreak's impact on travel and industry, many regions experienced a drop in air pollution. The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that methods to contain the spread of coronavirus, such as quarantines and travel bans, resulted in a 25% reduction of carbon emission in China.[488][489] In the first month of lockdowns, China produced approximately 200 million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide than the same period in 2019, due to the reduction in air traffic, oil refining, and coal consumption.[489] Between 1 January and 11 March 2020, the European Space Agency observed a marked decline in nitrous oxide emissions from cars, power plants and factories in the Po Valley region in northern Italy, coinciding with lockdowns in the region.[490] In Venice, the water in the canals cleared up and experienced an increased presence of fish and waterfowl; the Venice mayor's office clarified that the increase in water clarity was due to the settling of sediment that is disturbed by boat traffic and mentioned the decrease in air pollution along the waterways.[491]

Despite a temporary decline in global carbon emissions, the International Energy Agency warned that the economic turmoil caused by the coronavirus outbreak may prevent or delay companies from investing in green energy.[492] However, extended quarantine periods have boosted adoption of remote work policies.[493][494]

As a consequence of the unprecedented use of disposable face masks, significant numbers are entering the natural environment and in particular, to rivers and seawater. In some cases, the masks have been washed onto beaches where they are accumulating. This accumulation has been reported on beaches in Hong Kong and is expected to add to the worldwide burden of plastic waste and the detrimental effects of this waste to marine life.[495]

Culture

Another recent and rapidly accelerating fallout of the disease is the cancellation of religious services, major events in sports, the film industry, and other societal events, such as music festivals and concerts, technology conferences, fashion shows and sports.[496][497]