CD38

CD38 (cluster of differentiation 38), also known as cyclic ADP ribose hydrolase is a glycoprotein[5] found on the surface of many immune cells (white blood cells), including CD4+, CD8+, B lymphocytes and natural killer cells. CD38 also functions in cell adhesion, signal transduction and calcium signaling.[6]

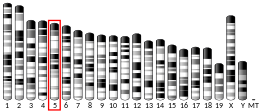

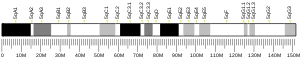

In humans, the CD38 protein is encoded by the CD38 gene which is located on chromosome 4.[7][8] CD38 is a paralog of CD157, which is also located on chromosome 4 (4p15) in humans.[9]

History and tissue distribution

CD38 was first identified in 1980 as a surface marker (cluster of differentiation) of thymus cell lymphocytes.[10][11] In 1992 it was additionally described as a surface marker on B cells, monocytes, and natural killer cells (NK cells).[10] About the same time, CD38 was discovered to be not simply a marker of cell types, but an activator of B cells and T cells.[10] In 1992 the enzymatic activity of CD38 was discovered, having the capacity to synthesize the calcium-releasing second messengers cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP).[10]

CD38 is most frequently found on plasma B cells, followed by natural killer cells, followed by B cells and T cells, and then followed by a variety of cell types.[12]

Function

CD38 can function either as a receptor or as an enzyme.[13] As a receptor, CD38 can attach to CD31 on the surface of T cells, thereby activating those cells to produce a variety of cytokines.[13]

CD38 is a multifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of ADP ribose (ADPR) (97%) and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) (3%) from NAD+.[14][15] CD38 can be a major regulator of NAD+ levels because 100 molecules of NAD+ is required to generate one molecule of cADPR.[16] CD38 also hydrolyzes cADPR to ADPR.[14] When nicotinic acid is present under acidic conditions, CD38 can hydrolyze nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+) to NAADP.[14][17]

These reaction products are essential for the regulation of intracellular Ca2+.[18] CD38 occurs not only as an ectoezyme on cell outer surfaces, but also occurs on the inner surface of cell membranes, facing the cytosol performing the same enzymatic functions.[19]

CD38 is believed to control or influence neurotransmitter release in the brain by producing cADPR.[20] CD38 within the brain enables release of the affiliative neuropeptide oxytocin.[21]

Like CD38, CD157 is a member of the ADP-ribosyl cyclase family of enzymes that catalyze the formation of cADPR from NAD+, although CD157 is a much weaker catalyst than CD38.[22] The SARM1 enzyme also catalyzes the formation of cADPR from NAD+,[19] but SARM1 elevates cADPR much more efficiently than CD38.[23]

Clinical significance

The loss of CD38 function is associated with impaired immune responses, metabolic disturbances, and behavioral modifications including social amnesia possibly related to autism.[18][24]

CD31 on endothelial cells binds to the CD38 receptor on natural killer cells for those cells to attach to the endothelium.[25][26] CD38 on leukocytes attaching to CD16 on endothelial cells allows for leukocyte binding to blood vessel walls, and the passage of leukocytes through blood vessel walls.[9]

The cytokine interferon gamma and the Gram negative bacterial cell wall component lipopolysaccharide induce CD38 expression on macrophages.[26] Interferon gamma strongly induces CD38 expression on monocytes.[18] The cytokine tumor necrosis factor strongly induces CD38 on airway smooth muscle cells inducing cADPR-mediated Ca2+, thereby increasing dysfunctional contractility resulting in asthma.[27]

The CD38 protein is a marker of cell activation. It has been connected to HIV infection, leukemias, myelomas,[28] solid tumors, type II diabetes mellitus and bone metabolism, as well as some genetically determined conditions.

CD38 increases airway contractility hyperresponsiveness, is increased in the lungs of asthmatic patients, and amplifies the inflammatory response of airway smooth muscle of those patients.[15]

Increased expression of CD38 is an unfavourable diagnostic marker in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is associated with increased disease progression.[29]

Clinical application

CD38 inhibitors may be used as therapeutics for the treatment of asthma.[30]

CD38 has been used as a prognostic marker in leukemia.[31]

Daratumumab (Darzalex) which targets CD38 has been used in treating multiple myeloma.[32][33]

The use of Daratumumab can interfere with pre-blood transfusion tests, as CD38 is weakly expressed on the surface of erythrocytes. Thus, a screening assay for irregular antibodies against red blood cell antigens or a direct immunoglobulin test can produce false-positive results.[34] This can be sidelined by either pretreatment of the erythrocytes with dithiothreitol (DTT) or by using an anti-CD38 antibody neutralizing agent, e.g. DaraEx.

Nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) are NAD+ precursors, but when NR or NMN are administered, CD38 can degrade these precursors before they can enter cells.[35]

Inhibitors

- Cassic acid (Rhein) [36]

- CD38-IN-78c [37]

- Chrysanthemin (Kuromanin) [38]

- compound 1ai [39]

- compound 1am [40][41]

- Daratumumab [42]

Aging studies

A gradual increase in CD38 has been implicated in the decline of NAD+ with age.[43][44] Treatment of old mice with a specific CD38 inhibitor, 78c, prevents age-related NAD+ decline.[45] CD38 knockout mice have twice the levels of NAD+ and are resistant to age-associated NAD+ decline,[35] with dramatically increased NAD+ levels in major organs (liver, muscle, brain, and heart).[46] On the other hand, mice overexpressing CD38 exhibit reduced NAD+ and mitochondrial dysfuntion.[35]

Macrophages are believed to be primarily responsible for the age-related increase in CD38 expression and NAD+ decline.[47] Macrophages accumulate in visceral fat and other tissues with age, leading to chronic inflammation.[48] Secretions from senescent cells induce high levels of expression of CD38 on macrophages, which becomes the major cause of NAD+ depletion with age.[49]

Decline of NAD+ in the brain with age may be due to increased CD38 on astrocytes and microglia, leading to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.[20]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000004468 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029084 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Orciani M, Trubiani O, Guarnieri S, Ferrero E, Di Primio R (October 2008). "CD38 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of human hematopoietic cells". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 105 (3): 905–12. doi:10.1002/jcb.21887. PMID 18759251. S2CID 44430455.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: CD38 CD38 molecule".

- ^ Jackson DG, Bell JI (April 1990). "Isolation of a cDNA encoding the human CD38 (T10) molecule, a cell surface glycoprotein with an unusual discontinuous pattern of expression during lymphocyte differentiation". Journal of Immunology. 144 (7): 2811–5. PMID 2319135.

- ^ Nata K, Takamura T, Karasawa T, Kumagai T, Hashioka W, Tohgo A, Yonekura H, Takasawa S, Nakamura S, Okamoto H (February 1997). "Human gene encoding CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase/cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase): organization, nucleotide sequence and alternative splicing". Gene. 186 (2): 285–92. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00723-8. PMID 9074508.

- ^ a b Quarona V, Zaccarello G, Chillemi A (2013). "CD38 and CD157: a long journey from activation markers to multifunctional molecules". Cytometry Part B. 84 (4): 207–217. doi:10.1002/cyto.b.21092. PMID 23576305. S2CID 205732787.

- ^ a b c d Lee, H.C., ed. (2002). A Natural History of the Human CD38 Gene. In:Cyclic ADP-Ribose and NAADP. Springer Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0269-2_4. ISBN 978-1-4613-4996-9.

- ^ Reinherz EL, Kung PC, Schlossman SF (1980). "Discrete stages of human intrathymic differentiation: analysis of normal thymocytes and leukemic lymphoblasts of T-cell lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (3): 1588–1592. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.3.1588. PMC 348542. PMID 6966400.

- ^ van de Donk N, Richardson PG, Malavasi F (2018). "CD38 antibodies in multiple myeloma: back to the future". Blood. 131 (1): 13–29. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-740944. PMID 29118010.

- ^ a b Nooka AK, Kaufman JL, Hofmeister CC, Joseph NS (2019). "Daratumumab in multiple myeloma". Cancer. 125 (14): 2364–2382. doi:10.1002/cncr.32065. PMID 30951198. S2CID 96435958.

- ^ a b c Kar A, Mehrotra S, Chatterjee S (2020). "CD38: T Cell Immuno-Metabolic Modulator". Cells. 9 (7): 1716. doi:10.3390/cells9071716. PMC 7408359. PMID 32709019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Guedes A, Dileepan M, Jude JA, Kannan MS (2020). "Role of CD38/cADPR signaling in obstructive pulmonary diseases". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 51: 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.04.007. PMC 7529733. PMID 32480246.

- ^ Braidy N, Berg J, Clement J, Sachdev P (2019). "Role of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide and Related Precursors as Therapeutic Targets for Age-Related Degenerative Diseases: Rationale, Biochemistry, Pharmacokinetics, and Outcomes". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 10 (2): 251–294. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7269. PMC 6277084. PMID 29634344.

- ^ Chini EN, Chini CC, Kato I, Takasawa S, Okamoto H (February 2002). "CD38 is the major enzyme responsible for synthesis of nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate in mammalian tissues". The Biochemical Journal. 362 (Pt 1): 125–30. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3620125. PMC 1222368. PMID 11829748.

- ^ a b c Malavasi F, Deaglio S, Funaro A, Ferrero E, Horenstein AL, Ortolan E, Vaisitti T, Aydin S (July 2008). "Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology". Physiological Reviews. 88 (3): 841–86. doi:10.1152/physrev.00035.2007. PMID 18626062.

- ^ a b Lee HC, Zhao YJ (2019). "Resolving the topological enigma in Ca 2+ signaling by cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 294 (52): 19831–19843. doi:10.1074/jbc.REV119.009635. PMC 6937575. PMID 31672920.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Guerreiro S, Privat A, Bressac L, Toulorge D (2020). "CD38 in Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation". Cells. 9 (2): 471. doi:10.3390/cells9020471. PMC 7072759. PMID 32085567.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tolomeo S, Chiao B, Lei Z, Chew SH, Ebstein RP (2020). "A Novel Role of CD38 and Oxytocin as Tandem Molecular Moderators of Human Social Behavior". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 115: 251–272. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.04.013. PMID 32360414. S2CID 216638884.

- ^ Higashida H, Hashii M, Tanaka Y, Matsukawa S (2019). "CD38, CD157, and RAGE as Molecular Determinants for Social Behavior". Cells. 9 (1): 62. doi:10.3390/cells9010062. PMC 7016687. PMID 31881755.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zhao ZY, Xie XJ, Li WH, Zhao YJ (2016). "A Cell-Permeant Mimetic of NMN Activates SARM1 to Produce Cyclic ADP-Ribose and Induce Non-apoptotic Cell Death". iScience. 15: 452–466. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.001. PMC 6531917. PMID 31128467.

- ^ Higashida H, Yokoyama S, Huang JJ, Liu L, Ma WJ, Akther S, Higashida C, Kikuchi M, Minabe Y, Munesue T (November 2012). "Social memory, amnesia, and autism: brain oxytocin secretion is regulated by NAD+ metabolites and single nucleotide polymorphisms of CD38". Neurochemistry International. 61 (6): 828–38. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.030. hdl:2297/32816. PMID 22366648. S2CID 33172185.

- ^ Zambello R, Barilà G, Sabrina Manni S (2020). "NK cells and CD38: Implication for (Immuno)Therapy in Plasma Cell Dyscrasias". Cells. 9 (3): 768. doi:10.3390/cells9030768. PMC 7140687. PMID 32245149.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Glaría E, Valledor AF (2020). "Roles of CD38 in the Immune Response to Infection". Cells. 9 (1): 228. doi:10.3390/cells9010228. PMC 7017097. PMID 31963337.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Deshpande DA, Guedes A, Graeff R, Dogan S (2018). "CD38/cADPR Signaling Pathway in Airway Disease: Regulatory Mechanisms". Mediators of Inflammation. 2018: 8942042. doi:10.1155/2018/8942042. PMC 5821947. PMID 29576747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Marlein CR, Piddock RE, Mistry JJ, Zaitseva L, Hellmich C, Horton RH, Zhou Z, Auger MJ, Bowles KM, Rushworth SA (January 2019). "CD38-driven mitochondrial trafficking promotes bioenergetic plasticity in multiple myeloma". Cancer Research. 79 (9): 2285–2297. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0773. PMID 30622116.

- ^ Burgler S (2015). "Role of CD38 Expression in Diagnosis and Pathogenesis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Its Potential as Therapeutic Target". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 35 (5): 417–32. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v35.i5.50. PMID 26853852.

- ^ Deshpande DA, Guedes AG, Lund FE, Kannan MS (2017). "CD38 in the pathogenesis of allergic airway disease: Potential therapeutic targets". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 172: 116–126. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.12.002. PMC 5346344. PMID 27939939.

- ^ Deaglio S, Mehta K, Malavasi F (January 2001). "Human CD38: a (r)evolutionary story of enzymes and receptors". Leukemia Research. 25 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0145-2126(00)00093-X. PMID 11137554.

- ^ McKeage K (February 2016). "Daratumumab: First Global Approval". Drugs. 76 (2): 275–81. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0536-1. PMID 26729183. S2CID 11977989.

- ^ Xia C, Ribeiro M, Scott S, Lonial S (October 2016). "Daratumumab: monoclonal antibody therapy to treat multiple myeloma". Drugs of Today. 52 (10): 551–560. doi:10.1358/dot.2016.52.10.2543308. PMID 27910963.

- ^ de Vooght KM, Lozano M, Bueno JL, Alarcon A, Romera I, Suzuki K, Zhiburt E, Holbro A, Infanti L, Buser A, Hustinx H, Deneys V, Frelik A, Thiry C, Murphy M, Staves J, Selleng K, Greinacher A, Kutner JM, Bonet Bub C, Castilho L, Kaufman R, Colling ME, Perseghin P, Incontri A, Dassi M, Brilhante D, Macedo A, Cserti-Gazdewich C, Pendergrast JM, Hawes J, Lundgren MN, Storry JR, Jain A, Marwaha N, Sharma RR (May 2018). "Vox Sanguinis International Forum on typing and matching strategies in patients on anti-CD38 monoclonal therapy: summary". Vox Sanguinis. 113 (5): 492–498. doi:10.1111/vox.12653. PMID 29781081. S2CID 29156699.

- ^ a b c Cambronne XA, Kraus WL (2020). "Location, Location, Location: Compartmentalization of NAD + Synthesis and Functions in Mammalian Cells". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 45 (10): 858–873. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2020.05.010. PMC 7502477. PMID 32595066.

- ^ Blacher E, Ben Baruch B, Levy A, Geva N, Green KD, Garneau-Tsodikova S, et al. (March 2015). "Inhibition of glioma progression by a newly discovered CD38 inhibitor". International Journal of Cancer. 136 (6): 1422–33. doi:10.1002/ijc.29095. PMID 25053177.

- ^ Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Kanamori KS, Warner GM, Caride A, de Oliveira GC, et al. (May 2018). "+ Decline". Cell Metabolism. 27 (5): 1081–1095.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.016. PMID 29719225.

- ^ Kellenberger E, Kuhn I, Schuber F, Muller-Steffner H (July 2011). "Flavonoids as inhibitors of human CD38". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 21 (13): 3939–42. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.022. PMID 21641214.

- ^ Becherer JD, Boros EE, Carpenter TY, Cowan DJ, Deaton DN, Haffner CD, et al. (September 2015). "Discovery of 4-Amino-8-quinoline Carboxamides as Novel, Submicromolar Inhibitors of NAD-Hydrolyzing Enzyme CD38". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 58 (17): 7021–56. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00992. PMID 26267483.

- ^ Deaton DN, Haffner CD, Henke BR, Jeune MR, Shearer BG, Stewart EL, Stuart JD, Ulrich JC (May 2018). "2,4-Diamino-8-quinazoline carboxamides as novel, potent inhibitors of the NAD hydrolyzing enzyme CD38: Exploration of the 2-position structure-activity relationships". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 26 (8): 2107–2150. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2018.03.021. PMID 29576271.

- ^ Sepehri B, Ghavami R (January 2019). "Design of new CD38 inhibitors based on CoMFA modelling and molecular docking analysis of 4‑amino-8-quinoline carboxamides and 2,4-diamino-8-quinazoline carboxamides". SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research. 30 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1080/1062936X.2018.1545695. PMID 30489181.

- ^ Sidiqi MH, Gertz MA (February 2019). "Daratumumab for the treatment of AL amyloidosis". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 60 (2): 295–301. doi:10.1080/10428194.2018.1485914. PMC 6342668. PMID 30033840.

- ^ Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, Puranik AS, Schoon RA, Reid JM, Galina A, Chini EN (June 2016). "CD38 Dictates Age-Related NAD Decline and Mitochondrial Dysfunction through an SIRT3-Dependent Mechanism". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 1127–1139. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006. PMC 4911708. PMID 27304511.

- ^ Schultz MB, Sinclair DA (June 2016). "Why NAD(+) Declines during Aging: It's Destroyed". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 965–966. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.022. PMC 5088772. PMID 27304496.

- ^ Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Kanamori KS, Warner GM, Caride A, de Oliveira GC, Rud M, Samani A, Hein KZ, Huang R, Jurk D, Cho DS, Boslett JJ, Miller JD, Zweier JL, Passos JF, Doles JD, Becherer DJ, Chini EN (May 2018). "A Potent and Specific CD38 Inhibitor Ameliorates Age-Related Metabolic Dysfunction by Reversing Tissue NAD+ Decline". Cell Metabolism. 27 (5): 1081–1095.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.016. PMC 5935140. PMID 29719225.

- ^ Kang BE, Choi J, Stein S, Ryu D (2020). "Implications of NAD + boosters in translational medicine". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 50 (10): e13334. doi:10.1111/eci.13334. PMID 32594513. S2CID 220254270.

- ^ Yarbro JR, Emmons RS, Pence BD (2020). "Macrophage Immunometabolism and Inflammaging: Roles of Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, CD38, and NAD". Immunometabolism. 2 (3): e200026. doi:10.20900/immunometab20200026. PMC 7409778. PMID 32774895.

- ^ Oishi Y, Manabe I (2016). "Macrophages in age-related chronic inflammatory diseases". npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 2: 16018. doi:10.1038/npjamd.2016.18. PMC 5515003. PMID 28721272.

- ^ Covarrubias AJ, Kale A, Perrone R, Lopez-Dominguez JA, Pisco AO, Kasler HG, Schmidt MS, Heckenbach I, Kwok R, Wiley CD, Wong HS, Gibbs E, Iyer SS, Basisty N, Wu Q, Kim IJ, Silva E, Vitangcol K, Shin KO, Lee YM, Riley R, Ben-Sahra I, Ott M, Schilling B, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Ishihara K, Quake SR, Newman J, Brenner C, Campisi J, Verdin E (November 16, 2020). "Senescent cells promote tissue NAD + decline during ageing via the activation of CD38 + macrophages". Nature Metabolism. 2 (11): 1265–1283. doi:10.1038/s42255-020-00305-3. PMID 33199924.

Further reading

- States DJ, Walseth TF, Lee HC (December 1992). "Similarities in amino acid sequences of Aplysia ADP-ribosyl cyclase and human lymphocyte antigen CD38". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 17 (12): 495. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90337-9. PMID 1471258.

- Malavasi F, Funaro A, Roggero S, Horenstein A, Calosso L, Mehta K (March 1994). "Human CD38: a glycoprotein in search of a function". Immunology Today. 15 (3): 95–7. doi:10.1016/0167-5699(94)90148-1. PMID 8172650.

- Guse AH (May 1999). "Cyclic ADP-ribose: a novel Ca2+-mobilising second messenger". Cellular Signalling. 11 (5): 309–16. doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(99)00004-2. PMID 10376802.

- Funaro A, Malavasi F (1999). "Human CD38, a surface receptor, an enzyme, an adhesion molecule and not a simple marker". Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents. 13 (1): 54–61. PMID 10432444.

- Mallone R, Perin PC (2006). "Anti-CD38 autoantibodies in type? diabetes". Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 22 (4): 284–94. doi:10.1002/dmrr.626. PMC 2763400. PMID 16544364.

- Partidá-Sánchez S, Rivero-Nava L, Shi G, Lund FE (2007). "CD38: an ecto-enzyme at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immune responses". Crossroads between Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 590. pp. 171–83. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-34814-8_12. ISBN 978-0-387-34813-1. PMID 17191385.

- Jackson DG, Bell JI (April 1990). "Isolation of a cDNA encoding the human CD38 (T10) molecule, a cell surface glycoprotein with an unusual discontinuous pattern of expression during lymphocyte differentiation". Journal of Immunology. 144 (7): 2811–5. PMID 2319135.

- Dianzani U, Bragardo M, Buonfiglio D, Redoglia V, Funaro A, Portoles P, Rojo J, Malavasi F, Pileri A (May 1995). "Modulation of CD4 lateral interaction with lymphocyte surface molecules induced by HIV-1 gp120". European Journal of Immunology. 25 (5): 1306–11. doi:10.1002/eji.1830250526. PMID 7539755. S2CID 37717142.

- Nakagawara K, Mori M, Takasawa S, Nata K, Takamura T, Berlova A, Tohgo A, Karasawa T, Yonekura H, Takeuchi T (1995). "Assignment of CD38, the gene encoding human leukocyte antigen CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase/cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase), to chromosome 4p15". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 69 (1–2): 38–9. doi:10.1159/000133933. PMID 7835083.

- Tohgo A, Takasawa S, Noguchi N, Koguma T, Nata K, Sugimoto T, Furuya Y, Yonekura H, Okamoto H (November 1994). "Essential cysteine residues for cyclic ADP-ribose synthesis and hydrolysis by CD38". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (46): 28555–7. PMID 7961800.

- Takasawa S, Tohgo A, Noguchi N, Koguma T, Nata K, Sugimoto T, Yonekura H, Okamoto H (December 1993). "Synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose by human leukocyte antigen CD38 and inhibition of the hydrolysis by ATP". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (35): 26052–4. PMID 8253715.

- Nata K, Takamura T, Karasawa T, Kumagai T, Hashioka W, Tohgo A, Yonekura H, Takasawa S, Nakamura S, Okamoto H (February 1997). "Human gene encoding CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase/cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase): organization, nucleotide sequence and alternative splicing". Gene. 186 (2): 285–92. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00723-8. PMID 9074508.

- Feito MJ, Bragardo M, Buonfiglio D, Bonissoni S, Bottarel F, Malavasi F, Dianzani U (August 1997). "gp 120s derived from four syncytium-inducing HIV-1 strains induce different patterns of CD4 association with lymphocyte surface molecules". International Immunology. 9 (8): 1141–7. doi:10.1093/intimm/9.8.1141. PMID 9263011.

- Ferrero E, Malavasi F (October 1997). "Human CD38, a leukocyte receptor and ectoenzyme, is a member of a novel eukaryotic gene family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide+-converting enzymes: extensive structural homology with the genes for murine bone marrow stromal cell antigen 1 and aplysian ADP-ribosyl cyclase". Journal of Immunology. 159 (8): 3858–65. PMID 9378973.

- Deaglio S, Morra M, Mallone R, Ausiello CM, Prager E, Garbarino G, Dianzani U, Stockinger H, Malavasi F (January 1998). "Human CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase) is a counter-receptor of CD31, an Ig superfamily member". Journal of Immunology. 160 (1): 395–402. PMID 9551996.

- Yagui K, Shimada F, Mimura M, Hashimoto N, Suzuki Y, Tokuyama Y, Nata K, Tohgo A, Ikehata F, Takasawa S, Okamoto H, Makino H, Saito Y, Kanatsuka A (September 1998). "A missense mutation in the CD38 gene, a novel factor for insulin secretion: association with Type II diabetes mellitus in Japanese subjects and evidence of abnormal function when expressed in vitro". Diabetologia. 41 (9): 1024–8. doi:10.1007/s001250051026. PMID 9754820.

External links

- CD38+Antigens at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human CD38 genome location and CD38 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- GeneCard CD38 [1]

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P28907 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase/cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase 1) at the PDBe-KB.