Chlorpromazine: Difference between revisions

Reverted good faith edits by Deass (talk): Copy and past issues. (TW) |

updated out of date reference |

||

| Line 356: | Line 356: | ||

Chlorpromazine largely replaced [[electroconvulsive therapy]], [[psychosurgery]], and [[insulin shock therapy]].<ref name="healy1"/> By 1964, about 50 million people worldwide had taken it.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dh52dr.html|title=Drug for treating schizophrenia identified|publisher=pbs.org|accessdate=7 July 2010}}</ref> In 1955 there were 558,922 resident patients in American state and county psychiatric hospitals. By 1970, the number dropped to 337,619; by 1980 to 150,000, and by 1990 between 110,000 and 120,000 patients.<ref>{{Cite book |first1=James F. |last1=McKenzie |first2=R. R. |last2=Pinger |first3=Jerome Edward|last3=Kotecki |title=An introduction to community health |publisher=Jones and Bartlett Publishers |location=Boston |year=2008|pages=|isbn=0-7637-4634-7}} {{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> |

Chlorpromazine largely replaced [[electroconvulsive therapy]], [[psychosurgery]], and [[insulin shock therapy]].<ref name="healy1"/> By 1964, about 50 million people worldwide had taken it.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dh52dr.html|title=Drug for treating schizophrenia identified|publisher=pbs.org|accessdate=7 July 2010}}</ref> In 1955 there were 558,922 resident patients in American state and county psychiatric hospitals. By 1970, the number dropped to 337,619; by 1980 to 150,000, and by 1990 between 110,000 and 120,000 patients.<ref>{{Cite book |first1=James F. |last1=McKenzie |first2=R. R. |last2=Pinger |first3=Jerome Edward|last3=Kotecki |title=An introduction to community health |publisher=Jones and Bartlett Publishers |location=Boston |year=2008|pages=|isbn=0-7637-4634-7}} {{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> |

||

Chlorpromazine, in widespread use for 50 years, remains a "benchmark" drug in the treatment of schizophrenia, an effective drug although not perfect.<ref |

Chlorpromazine, in widespread use for 50 years, remains a "benchmark" drug in the treatment of schizophrenia, an effective drug although not perfect.<ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Adams|first1=CE|last2=Awad|first2=G|last3=Rathbone|first3=J|last4=Thornley|first4=B|last5=Soares-Weiser|first5=K|title=Chlorpromazine versus placebo for schizophrenia|journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=2014|issue=1|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD000284.pub3|pmid=24395698|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000284.pub3/abstract|accessdate=02 June 2014}}</ref></ref> The relative strengths or potencies of other antipsychotics are often ranked or measured against chlorpromazine in aliquots of 100 mg, termed ''chlorpromazine equivalents'' or CPZE.<ref name="Yorston">{{Cite journal|last1=Yorston|first1=G.|title=Chlorpromazine equivalents and percentage of British National Formulary maximum recommended dose in patients receiving high-dose antipsychotics |journal=Psychiatric Bulletin |volume=24 |pages=130 |year=2000 |doi=10.1192/pb.24.4.130|issue=4}}</ref> |

||

==Veterinary uses== |

==Veterinary uses== |

||

Revision as of 13:54, 2 June 2014

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Largactil, Thorazine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682040 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets and syrup available), rectal, IM, IV infusion |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 10-80% (Oral; large interindividual variation)[2] |

| Protein binding | 90-99%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, mostly CYP2D6-mediated[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 30±7 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Urine (43-65% in 24 hrs)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.042 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19ClN2S |

| Molar mass | 318.86 g/mol (free base) 355.33 g/mol (hydrochloride) g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Chlorpromazine (as chlorpromazine hydrochloride, abbreviated CPZ; marketed in the United States as Thorazine and elsewhere as Largactil or Megaphen) is a dopamine antagonist of the typical antipsychotic class of medications possessing additional antiadrenergic, antiserotonergic, anticholinergic and antihistaminergic properties used to treat schizophrenia.[4][5] First synthesized on December 11, 1950, chlorpromazine was the first drug developed with specific antipsychotic action, and would serve as the prototype for the phenothiazine class of drugs, which later grew to comprise several other agents. The introduction of chlorpromazine into clinical use has been described as the single greatest advance in psychiatric care, dramatically improving the prognosis of patients in psychiatric hospitals worldwide.[6]

Chlorpromazine works on a variety of receptors in the central nervous system, producing potent anticholinergic, antidopaminergic, antihistaminic, and antiadrenergic effects. Both the clinical indications and side effect profile of CPZ are determined by this broad action: its anticholinergic properties cause constipation, sedation, and hypotension, and help relieve nausea. It also has anxiolytic (anxiety-relieving) properties. Its antidopaminergic properties can cause extrapyramidal symptoms such as akathisia (restlessness, aka the 'Thorazine shuffle' where the patient walks almost constantly, despite having nowhere to go due to mandatory confinement, and takes small, shuffling steps) and dystonia. It is known to cause tardive dyskinesia, which can be irreversible.[7] In acute settings, it is often administered as a syrup, which has a faster onset of action than tablets, and can also be given by intramuscular injection. IV administration is very irritating and is not advised; its use is limited to severe hiccups, surgery, and tetanus.[8]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[9]

Medical uses

Chlorpromazine is classified as a low-potency typical antipsychotic and in the past was used in the treatment of both acute and chronic psychoses, including schizophrenia and the manic phase of bipolar disorder as well as amphetamine-induced psychoses. Low-potency antipsychotics have more anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, sedation and constipation, and lower rates of extrapyramidal side effects, while high-potency antipsychotics (such as haloperidol) have the reverse profile.[10]

Chlorpromazine has also been used in porphyria and as part of tetanus treatment. It still is recommended for short term management of severe anxiety and aggressive episodes. Resistant and severe hiccups, severe nausea/emesis and preanesthetic conditioning are other uses.[10][11] Symptoms of delirium in medically hospitalized AIDS patients have been effectively treated with low doses of chlorpromazine.[12]

Other

Chlorpromazine is occasionally used off-label for treatment of severe migraine.[13][14] It is often, particularly in a palliative setting, used in small doses to improve the nausea that opioid-treated cancer patients encounter and to intensify and prolong the analgesic action of the opioids given.[13][15]

Chlorpromazine has been shown to be the most effective substance against human infection by the brain-eating amoeba. One study concluded: "Chlorpromazine had the best therapeutic activity against Naegleria fowleri in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, it may be a more useful therapeutic agent for the treatment of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis than amphotericin B."[16]

In Germany, chlorpromazine still carries label indications for insomnia and severe pruritus, as well as preanesthesia.[17] It is also used in the withdrawal of heroin, but under medical supervision.

Adverse effects

Include the following (serious adverse effects appear in bold):[Note 1][2][3][18][19][20]

Very common

- Sedation

- Somnolence

- Extrapyramidal symptoms[Note 2]

- Weight gain

- Orthostatic hypotension[Note 3]

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

Common

- ECG changes[Note 4]

- Contact dermatitis

- Photosensitivity (sensitivity to light)

- Urticaria (hives)

- Maculopapular

- Petechial or oedematous reactions

- Hyperprolactinaemia[Note 5]

- Impaired thermoregulation[Note 6]

- Hyperglycaemia[Note 7]

- Other hypothalamic abnormalities[Note 8]

- Blurred vision

- Mental confusion

- Raised ANA titre

- Positive SLE cells

- Mydriasis[Note 9]

- Atonic colon

- Seizure[Note 10]

- Agitation

- Excitement

- Restlessness

- Pain at the injection site

- Injection site abscess

Uncommon

- Miosis[Note 11]

- Urinary retention[Note 12]

- Nasal congestion

- Nausea

- Obstipation

- Arrhythmias

- Skin pigmentation

- Glycosuria[Note 13]

- Hypoglycaemia[Note 14]

- Paralytic ileus

Rare

- Agranulocytosis[Note 15]

- Haemolytic anaemia[Note 16]

- Aplastic anaemia[Note 17]

- A-V block[Note 18]

- Hypertensive crises[Note 19]

- Thrombocytopenic purpura

- Exfoliative dermatitis

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis[Note 20]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[Note 21]

- Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH)[Note 22]

- Water retention

- Cholestatic jaundice

- Liver injury

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome[Note 23]

- Myasthenia gravis[Note 24]

Unknown frequency

- Leucopaenia[Note 25]

- Eosinophilia[Note 26]

- Pancytopaenia[Note 27]

- Priapism[Note 28]

- Photophobia[Note 29]

- Corneal deposits

- Respiratory depression[Note 30]

- Ventricular tachycardia

- QT interval prolongation

- Atrial fibrilation

- Hyperthermia[Note 31]

- Hypothermia[Note 32]

- Galactorrhoea[Note 33]

- Breast enlargement in either sex

- False-positive pregnancy tests

- Allergic reaction

- Fits

- Cerebral oedema[Note 34]

- Urinary incontinence

- Coagulation defects

- Nightmares

- Abnormality of cerebrospinal fluid proteins

- Dysphoria[Note 35]

- Catatonic excitement

- Narrow angle glaucoma

- Optic atrophy

- Pigmentary retinopathy

- Amenorrhoea[Note 36]

- Infertility

- Tardive dyskinesia[Note 37]

These antipsychotics have significant effects on gonadal hormones including significantly lower levels of estradiol and progesterone in women whereas men display significantly lower levels of testosterone and DHEA when undergoing antipsychotic drug treatment compared to controls.[21] According to one study of the effects on the reproductive system in rats treated with chlorpromazine there were significant decreases in the weight of the testis, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate gland. These effects were accompanied by a decline in sperm motility, sperm counts, viability, and serum levels of testosterone in chlorpromazine rats compared to control rats. It has been reported that a change in either the absolute or relative weight of an organ after a chemical is administered is an indication of the toxic effect of the chemical. Therefore, the observed change in the relative weight of the testis and other accessory reproductive organs in rats treated with chlorpromazine indicates that the drug might be toxic to these organs at least during the period of treatments. Furthermore, the weights of the kidney, heart, liver, and adrenal glands of these treated rats were not affected both during administration of the drug and recovery periods, suggesting that the drug is not toxic to these organs.[21]

There appears to be a dose-dependent risk for seizures with chlorpromazine treatment.[22] Tardive dyskinesia and akathisia are less commonly seen with chlorpromazine than they are with high potency typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol[23] or trifluoperazine, and some evidence suggests that, with conservative dosing, the incidence of such effects for chlorpromazine may be comparable to that of newer agents such as risperidone or olanzapine.[24]

Chlorpromazine is notorious for depositing ocular tissues when taken in high dosages for long periods of time. In one specific case a 59 year old schizophrenic man on chlorpromazine therapy with cumulative dosage of 2500 g resulted in multiple white deposits in the endothelium of both corneas. Confocal microscopy revealed significant pleomorphism and polymegethism of endothelial cells. The anterior lens capsules opacities were star- shaped and concentrated in the centre. In this patient chlorpromazine deposited mainly in the corneal endothelium, central anterior lens capsule and epithelial cells. This is common with many patients that receive high dosages of chlorpromazine.[25]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include:[2]

- Circulatory

- CNS depression

- Coma

- Drug intoxication

- Bone marrow suppression

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Hepatic failure

- Active liver disease

- Previous hypersensitivity (including jaundice, agranulocytosis, etc.) to phenothiazines, especially chlorpromazine, or any of the excipients in the formulation being used.

Relative contraindications include:[2]

- Epilepsy

- Parkinson's disease

- Myasthenia gravis

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Prostatic hypertrophy

Chlorpromazine has been shown to inhibit the human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) potassium channels. This is a serious side effect of the drug and could lead to death. When this occurs long QT syndrome (aLQTS) is acquired by the prolongation of the cardiac action potential due to a block in the cardiac ion channels and delayed repolarization of the heart. Patients with aLQTS are exposed to a higher chance of Torsade de pointes arrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest.[26]

Interactions

Consuming food prior to taking chlorpromazine orally limits its absorption, likewise cotreatment with benztropine can also reduce chlorpromazine absorption.[2] Alcohol can also reduce chlorpromazine absorption.[2] Antacids slow chlorpromazine absorption.[2] Lithium and chronic treatment with barbiturates can increase chlorpromazine clearance significantly.[2] Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can decrease chlorpromazine clearance and hence increase chlorpromazine exposure.[2] Cotreatment with CYP1A2 inhibitors like ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamineor vemurafenib can reduce chlorpromazine clearance and hence increase exposure and potentially also adverse effects.[2] Chlorpromazine can also potentiate the CNS depressant effects of drugs like barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioids, lithium and anaesthetics and hence increase the potential for adverse effects such as respiratory depression and sedation.[2]

It is also a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6 and also a substrate for CYP2D6 and hence can inhibit its own metabolism.[10] It can also inhibit the clearance of CYP2D6 substrates such as dextromethorphan and hence also potentiate their effects.[10] Other drugs like codeine and tamoxifen which require CYP2D6-mediated activation into their respective active metabolites may have their therapeutic effects attenuated.[10] Likewise CYP2D6 inhibitors such as paroxetine or fluoxetine can reduce chlorpromazine clearance and hence increase serum levels of chlorpromazine and hence potentially also its adverse effects.[2] Chlorpromazine also reduces phenytoin levels and increases valproic acid levels.[2] It also reduces propanolol clearance and antagonises the therapeutic effects of antidiabetic agents, levodopa (a Parkinson's medication. This is likely due to the fact that chlorpromazine antagonises the D2 receptor which is one of the receptors dopamine, a levodopa metabolite, activates), amfetamines and anticoagulants.[2] It may also interact with anticholinergic drugs such as orphenadrine to produce hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar).[2]

Chlorpromazine may also interact with epinephrine (adrenaline) to produce a paradoxical fall in blood pressure.[2]Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and thiazide diuretics may also accentuate the orthostatic hypotension experienced by those receiving chlorpromazine treatment.[2] Quinidine may interact with chlorpromazine to increase myocardialdepression.[2] Likewise it may also antagonise the effects of clonidine and guanethidine.[2] It also may reduce the seizure threshold and hence a corresponding titration of anticonvulsant treatments should be considered.[2] Prochlorperazine and desferrioxamine may also interact with chlorpromazine to produce transient metabolic encephalopathy.[2]

Other drugs that prolong the QT interval such as quinidine, verapamil, amiodarone, sotalol and methadone may also interact with chlorpromazine to produce additive QT interval prolongation.[2]

Tolerance and withdrawal

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[27] While withdrawal symptoms can occur, there is no evidence that tolerance develops to the drug's antipsychotic effects. A patient can be maintained for years on a therapeutically effective dose without any decrease in effectiveness being reported. Tolerance appears to develop to the sedating effects of chlorpromazine when it is first administered. Tolerance also appears to develop to the extrapyramidal, parkinsonian and other neuroleptic effects, although this is debatable.[28]

A failure to notice withdrawal symptoms may be due to the relatively long half life of the drug resulting in the extremely slow excretion from the body. However, there are reports of muscular discomfort, exaggeration of psychotic symptoms and movement disorders, and difficulty sleeping when the antipsychotic drug is suddenly withdrawn, but after years of normal doses these effects are not normally seen.[28]

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

| Bioavailability | tmax | CSS | Protein bound | Vd | t1/2 | Details of metabolism | Excretion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-80% | 1–4 hours (Oral); 6–24 hours (IM) | 100-300 ng/mL | 90-99% | 10-35 L/kg (mean: 22 L/kg) | 30±7 hours | CYP2D6, CYP1A2-mediated into over 10 major metabolites.[10] The major routes of metabolism include hydroxylation, N-oxidation, sulphoxidation, demethylation, deamination and conjugation. There is little evidence supporting the development of metabolic tolerance or an increase in the metabolism of chlorpromazine due to microsomal liver enzymes following multiple doses of the drug.[29] | Urine (43-65% after 24 hours) | Its high degree of lipophilicity (fat solubility) allows it to be detected in the urine for up to 18 months.[2][30] Less than 1% of the unchanged drug is excreted via the kidneys in the urine. In which 20-70% is excreted as conjugated or unconjugated metabolites, whereas 5-6% is excreted in feces.[30] |

Pharmacodynamics and central effects

Chlorpromazine is a very effective antagonist of D2 dopamine receptors and similar receptors, such as D3 and D5. Unlike most other drugs of this genre, it also has a high affinity for D1 receptors. Blocking these receptors causes diminished neurotransmitter binding in the forebrain, resulting in many different effects. Dopamine, unable to bind with a receptor, causes a feedback loop that causes dopaminergic neurons to release more dopamine. Therefore, upon first taking the drug, patients will experience an increase in activity of dopaminergic neural activity. Eventually, dopamine production of the neurons will drop substantially and dopamine will be removed from the synaptic cleft. At this point, neural activity decreases greatly; the continual blockade of receptors only compounds this effect.[10]

Chlorpromazine acts as an antagonist (blocking agent) on different postsynaptic receptors:

- Dopamine receptors (subtypes D1, D2, D3 and D4), which account for its different antipsychotic properties on productive and unproductive symptoms, in the mesolimbic dopamine system accounts for the antipsychotic effect whereas the blockade in the nigrostriatal system produces the extrapyramidal effects

- Serotonin receptors (5-HT1 and 5-HT2), with anxiolytic, and antiaggressive properties as well as an attenuation of extrapyramidal side effects, but also leading to weight gain and ejaculation difficulties.

- Histamine receptors (H1 receptors, accounting for sedation, antiemetic effect, vertigo, and weight gain)

- α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors (accounting for sympatholytic properties, lowering of blood pressure, reflex tachycardia, vertigo, sedation, hypersalivation and incontinence as well as sexual dysfunction, but may also attenuate pseudoparkinsonism—controversial. Also associated with weight gain as a result of blockage of the adrenergic alpha 1 receptor)

- M1 and M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (causing anticholinergic symptoms such as dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, difficulty or inability to urinate, sinus tachycardia, electrocardiographic changes and loss of memory, but the anticholinergic action may attenuate extrapyramidal side effects).

The presumed effectiveness of the antipsychotic drugs relied on their ability to block dopamine receptors. This assumption arose from the dopamine hypothesis that maintains that both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are a result of excessive dopamine activity. Furthermore, psychomotor stimulants like cocaine that increase dopamine levels can cause psychotic symptoms if taken in excess.[31]

Chlorpromazine and other typical antipsychotics are primarily blockers of D2 receptors. In fact an almost perfect correlation exists between the therapeutic dose of a typical antipsychotic and the drug's affinity for the D2 receptor. Therefore, a larger dose is required if the drug’s affinity for the D2 receptor is relatively weak. A correlation exists between average clinical potency and affinity of the antipsychotics for dopamine receptors.[28] Chlorpromazine tends to have greater effect at serotonin receptors than at D2 receptors, which is notably the opposite effect of the other typical antipsychotics. Therefore, chlorpromazine with respect to its effects on dopamine and serotonin receptors is similar to the atypical antipsychotics than the typical antipsychotics.[28]

Chlorpromazine and other antipsychotics with sedative properties such as promazine and thioridazine are among the most potent agents at α-adrenergic receptors. Furthermore, they are also among the most potent antipsychotics at histamine H1 receptors. This finding is in agreement with the pharmaceutical development of chlorpromazine and other antipsychotics as anti-histamine agents. Furthermore, the brain has a higher density of histamine H1 receptors than any body organ examined which may account for why chlorpromazine and other phenothiazine antipsychotics are as potent at these sites as the most potent classical antihistamines.[32]

In addition to influencing the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine it has been reported that antipsychotic drugs could achieve glutamanergic effects. This mechanism involves direct effects on antipsychotic drugs on glutamate receptors. By using the technique of functional neurochemical assay chlorpromazine and phenothiazine derivatives have been shown to have inhibitory effects on NMDA receptors that appeared to be mediated by action at the Zn site. It was found that there is an increase of NMDA activity at low concentrations and suppression at high concentrations of the drug. No significant difference in glutamate and glycine activity from the effects of chlorpromazine were reported. Further work will be necessary to determine if the influence in NMDA receptors by antipsychotic drugs contributes to their effectiveness.[33]

Chlorpromazine does also act as FIASMA (functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase).[34]

Peripheral effects

Chlorpromazine is an antagonist to H1 receptors (provoking antiallergic effects), H2 receptors (reduction of forming of gastric juice), M1 and M2 receptors (dry mouth, reduction in forming of gastric juice) and some 5-HT receptors (different anti-allergic/gastrointestinal actions).

Because it acts on so many receptors, chlorpromazine is often referred to as a "dirty drug",[35] whereas the atypical antipsychotic amisulpride, for example, acts only on central D2 and D3 receptors and is therefore a "clean drug". Research still needs to be done to understand the implications of this fact.

Discontinuation

At regular intervals the treating physician should evaluate whether continued treatment is needed. The drug should never be discontinued suddenly, due to unpleasant withdrawal-symptoms, such as agitation, sleeplessness, states of anxiety, stomach pain, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Preferably the dose should be gradually reduced.[11]

Synthesis

The synthesis of chlorpromazine begins with the reaction of 1,4-dichloro-2-nitrobenzene with 2-bromobenzenethiol.[36][37][38] Hydrogen chloride is evolved as a by-product of this step and a thioether is formed as the product. Although not verified, it appears that the ortho chlorine is eliminated preferentially. In the second step the nitro group is reduced with hydrogen gas. Upon heating in Dimethylformamide (DMF) solvent, ring cyclization occurs. The 2-chloro-10H-phenothiazine thus produced is combined with 3-chloro-N,N-dimethylpropan-1-amine in the presence of sodamide base to form chlorpromazine.

History

In 1933, the French pharmaceutical company Laboratoires Rhône-Poulenc began to search for new anti-histamines. In 1947, it synthesized promethazine, a phenothiazine derivative, which was found to have more pronounced sedative and antihistaminic effects than earlier drugs.[40] A year later, the French surgeon Pierre Huguenard used promethazine together with pethidine as part of a cocktail to induce relaxation and indifference in surgical patients. Another surgeon, Henri Laborit, believed the compound stabilized the central nervous system by causing 'artificial hibernation', and described this state as 'sedation without narcosis'. He suggested to Rhône-Poulenc that they develop a compound with better stabilizing properties.[41] The chemist Paul Charpentier produced a series of compounds and selected the one with the least peripheral activity, known as RP4560 or chlorpromazine, on 11 December 1950. Simone Courvoisier conducted behavioural tests and found chlorpromazine produced indifference to aversive stimuli in rats. Chlorpromazine was distributed for testing to physicians between April and August 1951. Laborit trialled the medicine on at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris, using it as an anaesthetic booster in intravenous doses of 50 to 100 mg on surgery patients and confirming it as the best drug to date in calming and reducing shock, with patients reporting improved well being afterwards. He also noted its hypothermic effect and suggested it may induce artificial hibernation. Laborit thought this would allow the body to better tolerate major surgery by reducing shock, a novel idea at the time. Known colloquially as "Laborit's drug", chlorpromazine was released onto the market in 1953 by Rhône-Poulenc and given the trade name Largactil, derived from large "broad" and acti* "activity.[42]

Following on, Laborit considered whether chlorpromazine may have a role in managing patients with severe burns, Raynaud's phenomenon, or psychiatric disorders. At the Villejuif Mental Hospital in November 1951, he and Montassut administered an intravenous dose to psychiatrist Cornelio Quarti who was acting as a volunteer. Quarti noted the indifference, but fainted upon getting up to go to the toilet, and so further testing was discontinued (orthostatic hypotension is a possible side effect of chlorpromazine). Despite this, Laborit continued to push for testing in psychiatric patients during early 1952. Psychiatrists were reluctant initially, but on January 19, 1952, it was administered (alongside pethidine, pentothal and ECT) to Jacques Lh. a 24 year old manic patient, who responded dramatically, and was discharged after three weeks having received 855 mg of the drug in total.[42]

Pierre Deniker had heard about Laborit's work from his brother in law, who was a surgeon, and ordered chlorpromazine for a clinical trial at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris where he was Men's Service Chief.[42] Together with the Director of the hospital, Professor Jean Delay, they published first clinical trial in 1952, in which they treated 38 psychotic patients with daily injections of chlorpromazine without the use of other sedating agents.[43] The response was dramatic; treatment with chlorpromazine went beyond simple sedation with patients showing improvements in thinking and emotional behaviour.[4] They also found that doses higher than those used by Laborit were required, giving patients 75–100 mg daily.[42]

Deniker then visited America, where the publication of their work alerted the American psychiatric community that the new treatment might represent a real breakthrough. Heinz Lehmann of the Verdun Protestant Hospital in Montreal trialled it in 70 patients and also noted its striking effects, with patients' symptoms resolving after many years of unrelenting psychosis.[citation needed] By 1954, chlorpromazine was being used in the United States to treat schizophrenia, mania, psychomotor excitement, and other psychotic disorders.[10][44][45] Rhône-Poulenc licensed chlorpromazine to Smith Kline & French (today's GlaxoSmithKline) in 1953. In 1955 it was approved in the United States for the treatment of emesis (vomiting). The effect of this drug in emptying psychiatric hospitals has been compared to that of penicillin and infectious diseases.[43] But the popularity of the drug fell from the late 1960s as newer drugs came on the scene. From chlorpromazine a number of other similar antipsychotics were developed. It also led to the discovery of antidepressants.[46]

Chlorpromazine largely replaced electroconvulsive therapy, psychosurgery, and insulin shock therapy.[4] By 1964, about 50 million people worldwide had taken it.[47] In 1955 there were 558,922 resident patients in American state and county psychiatric hospitals. By 1970, the number dropped to 337,619; by 1980 to 150,000, and by 1990 between 110,000 and 120,000 patients.[48]

Chlorpromazine, in widespread use for 50 years, remains a "benchmark" drug in the treatment of schizophrenia, an effective drug although not perfect.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).</ref> The relative strengths or potencies of other antipsychotics are often ranked or measured against chlorpromazine in aliquots of 100 mg, termed chlorpromazine equivalents or CPZE.[49]

Veterinary uses

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Chlorpromazine is not registered for animal uses, but may be prescribed legally by veterinarians for animal use. It is primarily used as an antiemetic in dogs and cats, and it is commonly used to decrease nausea in animals that are too young for other common anti-emetics. It is also sometimes used as a preanesthetic and muscle relaxant in cattle, swine, sheep, and goats.[citation needed] It is generally contraindicated for use with horses, due to a high incidence of ataxia and altered mentation. Its use in food-producing animals has been banned in the EU according to the Council's regulation 37/2010.

Notes

- ^ Data on the exact incidence of the different adverse effects is greatly lacking so only rough approximations of adverse effect incidence is available

- ^ Refer to main text below for details on this adverse effect

- ^ A drop in blood pressure that results from standing up

- ^ A disturbance in the electrical cycle of the heart

- ^ Elevated serum levels of the lactation-related hormone prolactin. This in turn can result, in the short term, at least, in galactorrhoea (lactation that is unrelated to pregnancy or breastfeeding), gynaecomastia (swollen breast tissue), sexual dysfunction and amenorrhoea (the absence of the menstrual period in women). Whereas in the long-term hyperprolactinaemia can result in osteoporosis (brittle bones).

- ^ An impaired ability to regulate one's body temperature

- ^ High blood glucose (sugar) levels

- ^ The hypothalamus of the brain regulates the release of a number of hormones as well as a few "housekeeping" functions such as tight control over body temperature

- ^ Widening (dilation) of the pupils

- ^ Refer to the text below for details

- ^ Constriction of the pupils of the eyes

- ^ Being unable to pass urine

- ^ Glucose (sugar) in the urine due to there being too much glucose in the blood for the kidneys to reabsorb it all when filtrate goes through loop of henle in the nephrons of the kidney.

- ^ Low blood glucose (sugar)

- ^ Basically an exaggerated form of leucopaenia. It occurs when the white blood cell (WBC) count drops below 5% of the norm

- ^ Where the number of red blood cells of the body die breakdown to an abnormal extent. These cells carry oxygen across the body from the lungs

- ^ Where the bone marrow stops adequately (in order to replenish the blood cells that die off every day) producing new blood cells

- ^ An abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart which can lead to potentially fatal changes in heart rhythm

- ^ Dangerously (in the short-term) high blood pressure

- ^ A dangerous skin reaction

- ^ An autoimmune reaction

- ^ A potentially fatal collection of symptoms (i.e. syndrome) that results from an abnormally excessive release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH). This in turn increases the reabsorption of

- ^ A potentially fatal condition that is caused by dopamine receptor-blocking agents such as antipsychotics. It develops over a period of days or weeks and is characterised by rigidity, tremor, diarrhoea, tachycardia, altered mental status (e.g. confusion, mania, hallucinations, etc.) and hyperthermia (high body temperature)

- ^ An autoimmune condition in of which the body's defences attack the neuromuscular junction — the gap between muscle and nerve cells across which the nerves send messages to the muscle cells

- ^ An abnormally low number of white blood cells in the blood. These cells defend the body from infections and hence this can heighten one's risk of infections

- ^ An abnormally high number of eosinophils — the cells of the immune system that defends the body from parasites

- ^ An abnormally low number of all three major groups of blood cells including the red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets

- ^ A painful and sustained (usually a few hours) erection

- ^ Fear of light

- ^ A reduction in the normal homeostatic breathing reaction to reductions in plasmacarbon dioxide levels

- ^ High body temperature

- ^ Low body temperature

- ^ Lactation that is unassociated with lactation or breastfeeding

- ^ The accumulation of fluid in the tissues of the brain

- ^ Basically the opposite to euphoria

- ^ The absence of menstrual periods

- ^ An often irreversible and sometimes even fatal movement disorder characterised by involuntary, repetitive and purposeless movements of the face, extremities, lips or tongue. Usually takes a number of years to develop but in some it can appear within months or less since the initiation of antipsychotic treatment

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "PRODUCT INFORMATION LARGACTIL" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sanofi Aventis Pty Ltd. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "Chlorpromazine Hydrochloride 100mg/5ml Oral Syrup - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Rosemont Pharmaceuticals Limited. 6 August 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Healy, David (2004). The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. pp. 37–73. ISBN 978-0-674-01599-9. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yuhas, Daisy. "Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Remains A Challenge (Timeline)". Scientific American Mind (March 2013). Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Yuhas, Daisy. "Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Remains A Challenge (Timeline)". Scientific american Mind (March 2013). Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Diaz, Jaime (1997). How drugs influence behavior: a neuro behavioral approach. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-02-328764-0.

- ^ "Chlorpromazine -Thorazine Dilution Guidelines". GlobalRPh Inc. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Template:Cite isbn

- ^ a b American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (1 November 2008). "Chlorpromazine". PubMed Health. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- ^ Breitbart W; Marotta R; Platt MM; et al. (February 1996). "A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 153 (2): 231–7. PMID 8561204.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b Chlorpromazine. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Loga, P (April 2007). "Chlorpromazine in Migraine" (PDF). Emergency Medicine Journal. 24 (4): 297–300. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.047860. PMC 265824. PMID 17384391.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help) - ^ Richter, PA; Burk, MP (July–August 1992). "The potentiation of narcotic analgesics with phenothiazines". The Journal of Foot Surgery. 31 (4): 378–380. PMID 1357024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kim, JH; Jung, SY; Lee, YJ; Song, KJ; Kwon, D; Kim, K; Park, S; Im, KI; Shin, HJ (November 2008). "Effect of therapeutic chemical agents in vitro and on experimental meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 52 (11): 4010–4016. doi:10.1128/AAC.00197-08. PMC 2573150. PMID 18765686.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Propaphenin, Medicine and Disease information". EPG Online. 14 July 2001. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CHLORPROMAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated [Sandoz Inc]". DailyMed. Sandoz Inc. October 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "CHLORPROMAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE injection [West-ward Pharmaceutical Corp.]". DailyMed. West-ward Pharmaceutical Corp. June 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Largactil Injection - Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. Sanofi. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ a b Raji Y, Ifabunmi SO, Akinsomisoye OS, Morakinyo AO, Oloyo AK (2005). "Gonadal Responses to Antipsychotic Drugs: Chlorpromazine and Thioridazine Reversibly Suppress Testicular Functions in Albino Rats". International Journal of Pharmacology. 1 (3): 287–92. doi:10.3923/ijp.2005.287.292.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pisani, F; Oteri, G; Costa, C; Di Raimondo, G; Di Perri, R (2002). "Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold". Drug Safety. 25 (2): 91–110. doi:10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004. PMID 11888352.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leucht C, Kitzmantel M, Chua L, Kane J, Leucht S (2008). Leucht, Claudia (ed.). "Haloperidol versus chlorpromazine for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004278. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004278.pub2. PMID 18254045.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W (May 2003). "New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 361 (9369): 1581–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. PMID 12747876.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Razeghinejad, Mohammad Reza; Nowroozzadeh, Mohammad Hosein; Zamani, Mohammad; Amini, Nima (2008). "In vivoobservations of chlorpromazine ocular deposits in a patient on long-term chlorpromazine therapy". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 36 (6): 560–3. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01832.x. PMID 18954320.

- ^ Thomas D; Wu K; Kathöfer S; et al. (June 2003). "The antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine inhibits HERG potassium channels". British Journal of Pharmacology. 139 (3): 567–74. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705283. PMC 1573882. PMID 12788816.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Cite isbn

- ^ a b c d McKim,, William A. (2007). Drugs and behavior: an introduction to behavioral pharmacology (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-13-219788-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Dahl SG, Strandjord RE (April 1977). "Pharmacokinetics of chlorpromazine after single and chronic dosage". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 21 (4): 437–48. PMID 849674.

- ^ a b Yeung PK, Hubbard JW, Korchinski ED, Midha KK (1993). "Pharmacokinetics of chlorpromazine and key metabolites". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 45 (6): 563–9. doi:10.1007/BF00315316. PMID 8157044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Girault J, Greengard P (2004). "The neurobiology of dopamine signaling". Arch Neurol. 61 (5): 641–44. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.5.641. PMID 15148138.

- ^ Peroutka SJ, Synder SH (December 1980). "Relationship of neuroleptic drug effects at brain dopamine, serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, and histamine receptors to clinical potency". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (12): 1518–22. PMID 6108081.

- ^ Lidsky TI, Yablonsky-Alter E, Zuck LG, Banerjee SP (August 1997). "Antipsychotic drug effects on glutamatergic activity". Brain Research. 764 (1–2): 46–52. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00423-X. PMID 9295192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, Mühle C, Terfloth L, Groemer T, Spitzer G, Liedl K, Gulbins E, Tripal P (2011). Riezman, Howard (ed.). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082. PMID 21909365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Falkai, P; Vogeley K (April 2000). "The chances of new atypical substances". biopsychiatry.com. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ P. Charpentier, U.S. patent 2,645,640 (1953)

- ^ P. Charpentier, DE 910301 (1951)

- ^ P. Charpentier; P. Gailliot; R. Jacob; J. Gaudechon; P. Buisson (1952). "Recherches sur les dimé-thylaminopropyl-N phénothiazines substituées". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. 235. Paris: 59–60.

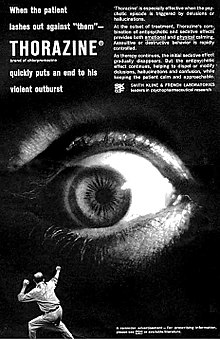

- ^ The text reads: When the patient lashes out against "them" - THORAZINE (brand of chlorpromazine) quickly puts an end to his violent outburst. 'Thorazine' is especially effective when the psychotic episode is triggered by delusions or hallucinations. At the outset of treatment, Thorazine's combination of antipsychotic and sedative effects provides both emotional and physical calming. Assaultive or destructive behavior is rapidly controlled. As therapy continues, the initial sedative effect gradually disappears. But the antipsychotic effect continues, helping to dispel or modify delusions, hallucinations and confusion, while keeping the patient calm and approachable. SMITH KLINE AND FRENCH LABORATORIES leaders in psychopharmaceutical research.

- ^ Healy, David (2004). "Explorations in a new world". The creation of psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-674-01599-9. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Healy, David (2004). "Explorations in a new world". The creation of psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-674-01599-9.

- ^ a b c d López-Muñoz, Francisco; Alamo, Cecilio; Cuenca, Eduardo; Shen, Winston W.; Clervoy, Patrick; Rubio, Gabriel (2005). "History of the discovery and clinical introduction of chlorpromazine". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 17 (3): 113–35. doi:10.1080/10401230591002002. PMID 16433053.

- ^ a b Turner T (January 2007). "Chlorpromazine: unlocking psychosis". BMJ. 334 (Suppl 1): s7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. PMID 17204765.

- ^ Long, James W. (1992). The Essential guide to prescription drugs. New York: HarperPerennial. pp. 321–325. ISBN 978-0-06-271534-0.

- ^ Reines, Brandon P (1990). "The Relationship between Laboratory and Clinical Studies in Psychopharmacologic Discovery". Perspectives on Medical Research. 2. Medical Research Modernization Society. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Healy, David (2004). "Introduction". The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780674015999. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Drug for treating schizophrenia identified". pbs.org. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ McKenzie, James F.; Pinger, R. R.; Kotecki, Jerome Edward (2008). An introduction to community health. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0-7637-4634-7. [page needed]

- ^ Yorston, G. (2000). "Chlorpromazine equivalents and percentage of British National Formulary maximum recommended dose in patients receiving high-dose antipsychotics". Psychiatric Bulletin. 24 (4): 130. doi:10.1192/pb.24.4.130.

Bibliography

- Baldessarini, Ross J.; Frank I. Tarazi (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of Psychosis and Mania". In Laurence Brunton, John Lazo, Keith Parker (eds.) (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Bezchlibnyk-Butler, K. Z. (2004). Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs (14th ed.). Hogrefe & Huber. ISBN 978-0-88937-284-9.

- Rote Liste (German Drug Compendium)

- Benkert, O. and H. Hippius. Psychiatrische Pharmakotherapie (German. 6th Edition, 1996)

- PDR Staff (2012). Physician's Desktop Reference (66th ed.). PDR Network. ISBN 978-1-56363-800-8.

- Heinrich, K. Psychopharmaka in Klinik und Praxis (German, 2nd Edition, 1983)

- Römpp, Chemielexikon (German, 9th Edition)

- NINDS Information Homepage (see External links section)

- Plumb, Dondal C. (2005). Plumb's Veterinary Drug Handbook (5th ed.). Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-8138-0518-4.

- "Methods of Execution". Clark County, IN Prosecuting Attorney web page. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)