Cannabigerol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.346.098 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

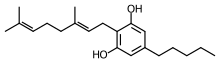

| Formula | C21H32O2 |

| Molar mass | 316.485 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Cannabigerol is one of more than 120 identified cannabinoid compounds found in the plant genus Cannabis.[1][2] Cannabigerol is the non-acidic form of cannabigerolic acid, the parent molecule from which other cannabinoids are synthesized. Cannabigerol is a minor constituent of cannabis.[3] During growth, most of the cannabigerol is converted into other cannabinoids, primarily tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabidiol, usually leaving somewhere below 1% cannabigerol in the plant.[4]

As of 2017, cannabigerol was under laboratory research to determine its pharmacological properties.[5] In vitro studies indicate it has high affinity as a α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, moderate affinity as a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, and low affinity as a CB1 receptor antagonist.[5][6] Other in vitro research shows it has low-affinity binding at CB2 receptors.[5]

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of cannabigerol begins by loading hexanoyl-CoA onto a polyketide synthase assembly protein and subsequent condensation with three molecules of malonyl-CoA.[7] This polyketide is cyclized to olivetolic acid via olivetolic acid cyclase, and then prenylated with a ten carbon isoprenoid precursor, geranyl pyrophosphate, using an aromatic prenyltransferase enzyme, geranyl-pyrophosphate—olivetolic acid geranyltransferase, to biosynthesize cannabigerolic acid, which can then be decarboxylated to yield cannabigerol.[3][8]

Research

As of 2018, no clinical research has been conducted to test the specific effects of cannabigerol in humans. Research is limited to studies in vitro and preliminary experiments on rodents, including laboratory models of colitis,[9][10] neurodegeneration,[11][12] cancer,[13][14] and feeding behavior,[15] among other normal or disease conditions where it may have effect.[5][16]

Legal status

Cannabigerol is not scheduled by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[citation needed] In the United States, it is not a controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act unless it is produced from parts of the cannabis plant that are scheduled.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Elsohly, M. A; Radwan, M. M; Gul, W; Chandra, S; Galal, A (2017). Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Vol. 103. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_1. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. PMID 28120229.

- ^ Turner, S. E; Williams, C. M; Iversen, L; Whalley, B. J (2017). Phytocannabinoids. Vol. 103. pp. 61–101. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_3. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. PMID 28120231.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Morales, P; Reggio, P. H; Jagerovic, N (2017). "An Overview on Medicinal Chemistry of Synthetic and Natural Derivatives of Cannabidiol". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 422. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00422. PMC 5487438. PMID 28701957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola, Oier; Soydaner, Umut; Öztürk, Ekin; Schibano, Daniele; Simsir, Yilmaz; Navarro, Patricia; Etxebarria, Nestor; Usobiaga, Aresatz (2016-02-26). "Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes". Journal of Natural Products. 79 (2): 324–331. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00949. ISSN 0163-3864. PMID 26836472.

- ^ a b c d Morales, P; Hurst, D. P; Reggio, P. H (2017). Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids - A Complex Picture. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Vol. 103. pp. 103–131. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_4. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. PMC 5345356. PMID 28120232.

- ^ Cascio MG, Gauson LA, Stevenson LA, Ross RA, Pertwee R (December 2009). "Evidence that the plant cannabinoid cannabigerol is a highly potent alpha(2)-adrenoceptor agonist and moderately potent 5HT receptor antagonist". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 129–141. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00515.x. PMC 2823359. PMID 20002104.

- ^ Page, Jonathan; et al. (2012). "Identification of olivetolic acid cyclase from Cannabis sativa reveals a unique catalytic route to plant polyketides". PNAS. 109 (31): 12811–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200330109. PMC 3411943. PMID 22802619.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ Meinhart H, Zenk; et al. (1998). "Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol". FEBS Letters. 427 (2): 283–285. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00450-5. PMID 9607329.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Couch, D. G; Maudslay, H; Doleman, B; Lund, J. N; O'Sullivan, S. E (2018). "The Use of Cannabinoids in Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 24 (4): 680–697. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy014. PMID 29562280.

- ^ Borrelli, F; Fasolino, I; Romano, B; Capasso, R; Maiello, F; Coppola, D; Orlando, P; Battista, G; Pagano, E; Di Marzo, V; Izzo, A. A (2013). "Beneficial effect of the non-psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease". Biochemical Pharmacology. 85 (9): 1306–16. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.017. PMID 23415610.

- ^ Valdeolivas, S; Navarrete, C; Cantarero, I; Bellido, M. L; Muñoz, E; Sagredo, O (2014). "Neuroprotective Properties of Cannabigerol in Huntington's Disease: Studies in R6/2 Mice and 3-Nitropropionate-lesioned Mice". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (1): 185–199. doi:10.1007/s13311-014-0304-z. PMC 4322067. PMID 25252936.

- ^ Granja, A. G; Carrillo-Salinas, F; Pagani, A; Gómez-Cañas, M; Negri, R; Navarrete, C; Mecha, M; Mestre, L; Fiebich, B. L; Cantarero, I; Calzado, M. A; Bellido, M. L; Fernandez-Ruiz, J; Appendino, G; Guaza, C; Muñoz, E (2012). "A cannabigerol quinone alleviates neuroinflammation in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 7 (4): 1002–16. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9399-3. PMID 22971837.

- ^ Śledziński, P; Zeyland, J; Słomski, R; Nowak, A (2018). "The current state and future perspectives of cannabinoids in cancer biology". Cancer Medicine. 7 (3): 765–775. doi:10.1002/cam4.1312. PMC 5852356. PMID 29473338.

- ^ Soderstrom, K; Soliman, E; Van Dross, R (2017). "Cannabinoids Modulate Neuronal Activity and Cancer by CB1 and CB2 Receptor-Independent Mechanisms". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 720. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00720. PMC 5641363. PMID 29066974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Brierley, D. I; Samuels, J; Duncan, M; Whalley, B. J; Williams, C. M (2016). "Cannabigerol is a novel, well-tolerated appetite stimulant in pre-satiated rats". Psychopharmacology. 233 (19): 3603–3613. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4397-4. PMC 5021742. PMID 27503475.

- ^ Fernández-Ruiz, J; Moro, M. A; Martínez-Orgado, J (2015). "Cannabinoids in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Stroke/Brain Trauma: From Preclinical Models to Clinical Applications". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 793–806. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0381-7. PMC 4604192. PMID 26260390.

- ^ "USC > Title 21 > Chapter 13 > Subchapter I > Part A > § 802. Definitions: (16)" (PDF). Government Publishing Office - US Code. 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)