Rhodopsin

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (March 2014) |

Rhodopsin, also known as visual purple, from Ancient Greek ῥόδον (rhódon, “rose”), due to its pinkish color, and ὄψις (ópsis, “sight”),[1] is a light-sensitive receptor protein. It is a biological pigment in photoreceptor cells of the retina. Rhodopsin is the primary pigment found in rod photoreceptors. Rhodopsins belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. They are extremely sensitive to light, enabling vision in low-light conditions.[2] Exposed to light, the pigment immediately photobleaches, and it takes about 45 minutes[3] to regenerate fully in humans.

Its discovery was reported by German physiologist Franz Christian Boll in 1876.[citation needed]

Structure

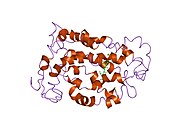

Rhodopsin consists of the protein moiety opsin and a reversibly covalently bound cofactor, retinal. Opsin, a bundle of seven transmembrane helices connected to each other by polypeptide loops, binds retinal (a photoreactive chromophore), which is located in a central pocket on the seventh helix at a lysine residue. The retinal lies horizontally with relation to the membrane. Each outer segment disc contains thousands of visual pigment molecules. About half the opsin is embedded within the lipid bilayer. Retinol is produced in the retina from Vitamin A, from dietary beta-carotene. Isomerization of 11-cis-retinal into all-trans-retinal by light induces a conformational change (bleaching) in opsin, continuing with metarhodopsin II, which activates the associated G protein transducin and triggers a Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate, second messenger, cascade.[3][4][5]

Rhodopsin of the rods most strongly absorbs green-blue light and, therefore, appears reddish-purple, which is why it is also called "visual purple".[citation needed] It is responsible for monochromatic vision in the dark.[3]

Several closely related opsins exist that differ only in a few amino acids and in the wavelengths of light that they absorb most strongly. Humans have four different other opsins besides rhodopsin. The photopsins are found in the different types of the cone cells of the retina and are the basis of color vision. They have absorption maxima for yellowish-green (photopsin I), green (photopsin II), and bluish-violet (photopsin III) light. The remaining opsin (melanopsin) is found in photosensitive ganglion cells and absorbs blue light most strongly.

In rhodopsin, the aldehyde of retinal is covalently linked to the amino group of a lysine residue on the protein in a protonated Schiff base (-NH+=CH-).[6] When rhodopsin absorbs light, its retinal cofactor isomerizes from the 11-cis to the all-trans configuration, and the protein subsequently undergoes a series of relaxations to accommodate the altered shape of the isomerized cofactor. The intermediates formed during this process were first investigated in the laboratory of George Wald, who received the Nobel prize for this research in 1967. The photoisomerization dynamics has been subsequently investigated with time-resolved IR spectroscopy and UV/Vis spectroscopy. A first photoproduct called photorhodopsin forms within 200 femtoseconds after irradiation, followed within picoseconds by a second one called bathorhodopsin with distorted all-trans bonds. This intermediate can be trapped and studied at cryogenic temperatures, and was initially referred to as prelumirhodopsin.[7] In subsequent intermediates lumirhodopsin and metarhodopsin I, the Schiff's base linkage to all-trans retinal remains protonated, and the protein retains its reddish color. The critical change that initiates the neuronal excitation involves the conversion of metarhodopsin I to metarhodopsin II, which is associated with deprotonation of the Schiff's base and change in color from red to yellow.[8] The structure of rhodopsin has been studied in detail via x-ray crystallography on rhodopsin crystals. Several models (e.g., the bicycle-pedal mechanism, hula-twist mechanism) attempt to explain how the retinal group can change its conformation without clashing with the enveloping rhodopsin protein pocket.[9][10][11]

Recent data support that it is a functional monomer- as opposed to a dimer- which was the paradigm of G-protein-coupled receptors for many years.[12]

Phototransduction

Rhodopsin is an essential G-protein receptor in phototransduction.

Function

Metarhodopsin II activates the G protein transducin (Gt) to activate the visual phototransduction pathway. When transducin's α subunit is bound to GTP, it activates cGMP phosphodiesterase. cGMP phosphodiesterase hydrolyzes cGMP (breaks it down). cGMP can no longer activate cation channels. This leads to the hyperpolarization of photoreceptor cells and a change in the rate of transmitter release by these photoreceptor cells.

Deactivation

Meta II is deactivated rapidly after activating transducin by rhodopsin kinase and arrestin.[13] The rhodopsin pigment must be regenerated for further phototransduction to occur. This means replacing all-trans-retinal with 11-cis-retinal and the decay of Meta II is crucial in this process. During the decay of Meta II, the Schiff base link that normally holds all-trans-retinal and the apoprotein opsin is hydrolyzed and becomes Meta III. In the rod outer segment, Meta III decays into separate all-trans-retinal and opsin.[13] A second product of Meta II decay is an all-trans-retinal opsin complex in which the all-trans-retinal has been translocated to second binding sites. Whether the Meta II decay runs into Meta III or the all-trans-retinal opsin complex seems to depend on the pH of the reaction. Higher pH tends to drive the decay reaction towards Meta III.[13]

Rhodopsin and retinal disease

Mutation of the rhodopsin gene is a major contributor to various retinopathies such as retinitis pigmentosa. In general, the disease-causing protein aggregates with ubiquitin in inclusion bodies, disrupts the intermediate filament network, and impairs the ability of the cell to degrade non-functioning proteins, which leads to photoreceptor apoptosis.[14] Other mutations on rhodopsin lead to X-linked congenital stationary night blindness, mainly due to constitutive activation, when the mutations occur around the chromophore binding pocket of rhodopsin.[15] Several other pathological states relating to rhodopsin have been discovered including poor post-Golgi trafficking, dysregulative activation, rod outer segment instability and arrestin binding.[15]

Microbial rhodopsins

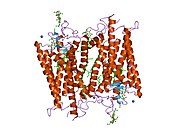

Some prokaryotes express proton pumps called bacteriorhodopsins, proteorhodopsins, and xanthorhodopsins to carry out phototrophy.[16] Like animal visual pigments, these contain a retinal chromophore (although it is an all-trans, rather than 11-cis form) and have seven transmembrane alpha helices; however, they are not coupled to a G protein. Prokaryotic halorhodopsins are light-activated chloride pumps.[16] Unicellular flagellate algae contain channelrhodopsins that act as light-gated cation channels when expressed in heterologous systems. Many other pro- and eukaryotic organisms (in particular, fungi such as Neurospora) express rhodopsin ion pumps or sensory rhodopsins of yet-unknown function. Very recently, a microbial rhodopsin with guanylyl cyclase activity has been discovered.[17] While all microbial rhodopsins have significant sequence homology to one another, they have no detectable sequence homology to the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family to which animal visual rhodopsins belong. Nevertheless, microbial rhodopsins and GPCRs are possibly evolutionarily related, based on the similarity of their three-dimensional structures. Therefore, they have been assigned to the same superfamily in Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP).[18]

References

- ^ Perception (2008), Guest Editorial Essay, Perception, p. 1

- ^ Litmann BJ, Mitchell DC (1996). "Rhodopsin structure and function". In Lee AG (ed.). Rhodopsin and G-Protein Linked Receptors, Part A (Vol 2, 1996) (2 Vol Set). Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press. pp. 1–32. ISBN 1-55938-659-2.

- ^ a b c Stuart JA, Brige RR (1996). "Characterization of the primary photochemical events in bacteriorhodopsin and rhodopsin". In Lee AG (ed.). Rhodopsin and G-Protein Linked Receptors, Part A (Vol 2, 1996) (2 Vol Set). Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press. pp. 33–140. ISBN 1-55938-659-2.

- ^ Hofmann KP, Heck M (1996). "Light-induced protein-protein interactions on the rod photoreceptor disc membrane". In Lee AG (ed.). Rhodopsin and G-Protein Linked Receptors, Part A (Vol 2, 1996) (2 Vol Set). Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press. pp. 141–198. ISBN 1-55938-659-2.

- ^ Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R, Jones BW (2010-03-01). "Webvision: Photoreceptors". University of Utah.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bownds, D; Wald G (1965). Nature. 205: 254–257. doi:10.1038/205254a0.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Yoshizawa, T; Wald G (1963). Nature. 197 (Mar 30): 1279–1286. doi:10.1038/1971279a0.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Matthews, R (1963). J Gen Physiol. 47: 215–240.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nakamichi H, Okada T (June 2006). "Crystallographic analysis of primary visual photochemistry". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45 (26): 4270–3. doi:10.1002/anie.200600595. PMID 16586416.

- ^ Schreiber M, Sugihara M, Okada T, Buss V (June 2006). "Quantum mechanical studies on the crystallographic model of bathorhodopsin". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45 (26): 4274–7. doi:10.1002/anie.200600585. PMID 16729349.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weingart O (September 2007). "The twisted C11-C12 bond of the rhodopsin chromophore--a photochemical hot spot". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (35): 10618–9. doi:10.1021/ja071793t. PMID 17691730.

- ^ Chabre M, le Maire M (July 2005). "Monomeric G-protein-coupled receptor as a functional unit". Biochemistry. 44 (27): 9395–403. doi:10.1021/bi050720o. PMID 15996094.

- ^ a b c Heck M, Schädel SA, Maretzki D, Bartl FJ, Ritter E, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP (January 2003). "Signaling states of rhodopsin. Formation of the storage form, metarhodopsin III, from active metarhodopsin II". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (5): 3162–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209675200. PMC 1364529. PMID 12427735.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Saliba RS, Munro PM, Luthert PJ, Cheetham ME (15 July 2002). "The cellular fate of mutant rhodopsin: quality control, degradation and aggresome formation". J. Cell. Sci. 115 (Pt 14): 2907–18. PMID 12082151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mendes HF, van der Spuy J, Chapple JP, Cheetham ME (April 2005). "Mechanisms of cell death in rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa: implications for therapy". Trends Mol Med. 11 (4): 177–85. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.007. PMID 15823756.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bryant DA, Frigaard NU (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends Microbiol. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- ^ U. Scheib, K. Stehfest, C. E. Gee, H. G. Körschen, R. Fudim, T. G. Oertner, P. Hegemann (2015). "The rhodopsin-guanylyl cyclase of the aquatic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii enables fast optical control of cGMP signaling". Science Signaling. 8 (389): r8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://scop.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/scop/data/scop.b.g.e.b.html.

Further reading

External links

- Rhodopsin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R, Jones BW (2010-03-01). "Webvision Home Page: The organization of the retina and visual system". University of Utah.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Rhodopsin Protein

- Photoisomerization of rhodopsin, animation.

- Rhodopsin and the eye, summary with pictures.

- UMich Orientation of Proteins in Membranes families/superfamily-6 - Calculated spatial positions of rhodopsin-like proteins in membrane