CD9

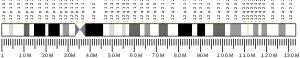

CD9 is a gene encoding a protein that is a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily also known as the tetraspanin family. It is a cell surface glycoprotein that consists of four transmembrane regions and has two extracellular loops that contain disulfide bonds which are conserved throughout the tetraspanin family.[5][6][7] Also containing distinct palmitoylation sites that allows CD9 to interact with lipids and other proteins.[5][8][9]

Function

[edit]Tetraspanin proteins are involved in a multitude of biological processes such as adhesion, motility, membrane fusion, signaling and protein trafficking.[5][10] Tetraspanins play a role in many biological processes because of their ability to interact with many different proteins including interactions between each other. Their distinct palmitoylation sites allow them to organize on the membrane into tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEM).[11][8][10] These TEMs are thought to play a role in many cellular processes including exosome biogenesis.[12] CD9 is commonly used as a marker for exosomes as it is contained on their surface.[11][10][13][14]

However, in some cases CD9 plays a larger role in the ability of exosomes to be more or less pathogenic. Shown in HIV-1 infection, exosomes are able to enhance HIV-1 entry through tetraspanin CD9 and CD81.[15] However, expression of CD9 on the cellular membrane seems to decrease the viral entry of HIV-1.[16][17]

CD9 has a diverse role in cellular processes as it has also been shown to trigger platelet activation and aggregation.[18] It forms a alphaIIbbeta3-CD9-CD63 complex on the surface of platelets that interacts directly with other cells such as neutrophils which may assist in immune response.[11][19] In addition, the protein appears to promote muscle cell fusion and support myotube maintenance.[20][21] Also, playing a key role in egg-sperm fusion during mammalian fertilization.[9] While oocytes are ovulated, CD9-deficient oocytes do not properly fuse with sperm upon fertilization.[22] CD9 is located in the microvillar membrane of the oocytes and also appears to intervene in maintaining the normal shape of oocyte microvilli.[23]

CD9 can also modulate cell adhesion[24] and migration.[25][26] This function makes CD9 of interest when studying cancer and cancer metastasis. However, it seems CD9 has a varying role in different types of cancers. Studies showed that CD9 expression levels have an inverse correlation to metastatic potential or patient survival. The over expression of CD9 was shown to decrease metastasis in certain types of melanoma, breast, lung, pancreas and colon carcinomas.[27][28][29][30][31] However in other studies, CD9 has been shown to increase migration or be highly expressed in metastatic cancers in various cell lines such as lung cancer,[25] scirrhous-type gastric cancer,[26] hepatocellular carcinoma,[32] acute lymphoblastic leukemia,[33] and breast cancer. Suggesting based on the cancer CD9 can be a tumor suppressor or promotor. [34] It has also been suggested that CD9 has an effect on the ability for cancer cells to develop chemoresistance.

Additionally, CD9 has been shown to block adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to wounds. The adhesion is essential for infection of the wound.[35] This suggests that CD9 could be of possible use to as treatment for skin infection by Staphylococcus aureus.

Interactions

[edit]CD9 has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000010278 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030342 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c Andreu Z, Yáñez-Mó M (2014). "Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 342. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00442. PMC 4165315. PMID 25278937.

- ^ "CD9 CD9 molecule [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ "CD9 Gene - GeneCards | CD9 Protein | CD9 Antibody". www.genecards.org. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ a b Yáñez-Mó M, Barreiro O, Gordon-Alonso M, Sala-Valdés M, Sánchez-Madrid F (September 2009). "Tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: a functional unit in cell plasma membranes". Trends in Cell Biology. 19 (9): 434–46. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.004. PMID 19709882.

- ^ a b Yang XH, Kovalenko OV, Kolesnikova TV, Andzelm MM, Rubinstein E, Strominger JL, Hemler ME (May 2006). "Contrasting effects of EWI proteins, integrins, and protein palmitoylation on cell surface CD9 organization". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (18): 12976–85. doi:10.1074/jbc.M510617200. PMID 16537545.

- ^ a b c Hemler ME (October 2005). "Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 6 (10): 801–11. doi:10.1038/nrm1736. PMID 16314869. S2CID 5906694.

- ^ a b c d Israels SJ, McMillan-Ward EM, Easton J, Robertson C, McNicol A (January 2001). "CD63 associates with the alphaIIb beta3 integrin-CD9 complex on the surface of activated platelets". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 85 (1): 134–41. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1612916. PMID 11204565. S2CID 28721583.

- ^ Perez-Hernandez D, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Jorge I, López-Martín S, Ursa A, Sánchez-Madrid F, et al. (April 2013). "The intracellular interactome of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains reveals their function as sorting machineries toward exosomes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (17): 11649–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.445304. PMC 3636856. PMID 23463506.

- ^ Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, Chen TS, et al. (May 2010). "Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury". Stem Cell Research. 4 (3): 214–22. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. PMID 20138817.

- ^ Sumiyoshi N, Ishitobi H, Miyaki S, Miyado K, Adachi N, Ochi M (October 2016). "The role of tetraspanin CD9 in osteoarthritis using three different mouse models". Biomedical Research. 37 (5): 283–291. doi:10.2220/biomedres.37.283. PMID 27784871.

- ^ Sims B, Farrow AL, Williams SD, Bansal A, Krendelchtchikov A, Matthews QL (June 2018). "Tetraspanin blockage reduces exosome-mediated HIV-1 entry". Archives of Virology. 163 (6): 1683–1689. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3737-6. PMC 5958159. PMID 29429034.

- ^ Gordón-Alonso M, Yañez-Mó M, Barreiro O, Alvarez S, Muñoz-Fernández MA, Valenzuela-Fernández A, Sánchez-Madrid F (October 2006). "Tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 modulate HIV-1-induced membrane fusion". Journal of Immunology. 177 (8): 5129–37. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5129. PMID 17015697.

- ^ Thali M (2009). "The roles of tetraspanins in HIV-1 replication". HIV Interactions with Host Cell Proteins. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 339. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 85–102. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02175-6_5. ISBN 978-3-642-02174-9. PMC 4067973. PMID 20012525.

- ^ Rubinstein E, Billard M, Plaisance S, Prenant M, Boucheix C (September 1993). "Molecular cloning of the mouse equivalent of CD9 antigen". Thrombosis Research. 71 (5): 377–83. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(93)90162-h. PMID 8236164.

- ^ Yun SH, Sim EH, Goh RY, Park JI, Han JY (2016). "Platelet Activation: The Mechanisms and Potential Biomarkers". BioMed Research International. 2016: 9060143. doi:10.1155/2016/9060143. PMC 4925965. PMID 27403440.

- ^ Tachibana I, Hemler ME (August 1999). "Role of transmembrane 4 superfamily (TM4SF) proteins CD9 and CD81 in muscle cell fusion and myotube maintenance". The Journal of Cell Biology. 146 (4): 893–904. doi:10.1083/jcb.146.4.893. PMC 2156130. PMID 10459022.

- ^ Charrin S, Latil M, Soave S, Polesskaya A, Chrétien F, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E (2013). "Normal muscle regeneration requires tight control of muscle cell fusion by tetraspanins CD9 and CD81". Nature Communications. 4: 1674. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1674C. doi:10.1038/ncomms2675. PMID 23575678.

- ^ Le Naour F, Rubinstein E, Jasmin C, Prenant M, Boucheix C (January 2000). "Severely reduced female fertility in CD9-deficient mice". Science. 287 (5451): 319–21. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..319L. doi:10.1126/science.287.5451.319. PMID 10634790.

- ^ Runge KE, Evans JE, He ZY, Gupta S, McDonald KL, Stahlberg H, et al. (April 2007). "Oocyte CD9 is enriched on the microvillar membrane and required for normal microvillar shape and distribution". Developmental Biology. 304 (1): 317–25. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.041. PMID 17239847.

- ^ Machado-Pineda Y, Cardeñes B, Reyes R, López-Martín S, Toribio V, Sánchez-Organero P, et al. (2018). "CD9 Controls Integrin α5β1-Mediated Cell Adhesion by Modulating Its Association With the Metalloproteinase ADAM17". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 2474. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02474. PMC 6230984. PMID 30455686.

- ^ a b Blake DJ, Martiszus JD, Lone TH, Fenster SD (November 2018). "Ablation of the CD9 receptor in human lung cancer cells using CRISPR/Cas alters migration to chemoattractants including IL-16". Cytokine. 111: 567–570. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2018.05.038. PMC 8711597. PMID 29884309. S2CID 46997236.

- ^ a b Miki Y, Yashiro M, Okuno T, Kitayama K, Masuda G, Hirakawa K, Ohira M (March 2018). "CD9-positive exosomes from cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulate the migration ability of scirrhous-type gastric cancer cells". British Journal of Cancer. 118 (6): 867–877. doi:10.1038/bjc.2017.487. PMC 5886122. PMID 29438363.

- ^ Mimori K, Mori M, Shiraishi T, Tanaka S, Haraguchi M, Ueo H, et al. (March 1998). "Expression of ornithine decarboxylase mRNA and c-myc mRNA in breast tumours". International Journal of Oncology. 12 (3): 597–601. doi:10.3892/ijo.12.3.597. PMID 9472098.

- ^ Higashiyama M, Taki T, Ieki Y, Adachi M, Huang CL, Koh T, et al. (December 1995). "Reduced motility related protein-1 (MRP-1/CD9) gene expression as a factor of poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer". Cancer Research. 55 (24): 6040–4. doi:10.1016/0169-5002(96)87780-4. PMID 8521390.

- ^ Ikeyama S, Koyama M, Yamaoko M, Sasada R, Miyake M (May 1993). "Suppression of cell motility and metastasis by transfection with human motility-related protein (MRP-1/CD9) DNA". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 177 (5): 1231–7. doi:10.1084/jem.177.5.1231. PMC 2191011. PMID 8478605.

- ^ Sho M, Adachi M, Taki T, Hashida H, Konishi T, Huang CL, et al. (October 1998). "Transmembrane 4 superfamily as a prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer". International Journal of Cancer. 79 (5): 509–16. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981023)79:5<509::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-x. PMID 9761121. S2CID 19842716.

- ^ Ovalle S, Gutiérrez-López MD, Olmo N, Turnay J, Lizarbe MA, Majano P, et al. (November 2007). "The tetraspanin CD9 inhibits the proliferation and tumorigenicity of human colon carcinoma cells". International Journal of Cancer. 121 (10): 2140–52. doi:10.1002/ijc.22902. PMID 17582603. S2CID 22410504.

- ^ Lin Q, Peng S, Yang Y (July 2018). "Inhibition of CD9 expression reduces the metastatic capacity of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line MHCC97-H". International Journal of Oncology. 53 (1): 266–274. doi:10.3892/ijo.2018.4381. PMID 29749468.

- ^ Liang P, Miao M, Liu Z, Wang H, Jiang W, Ma S, et al. (2018). "CD9 expression indicates a poor outcome in acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Cancer Biomarkers. 21 (4): 781–786. doi:10.3233/CBM-170422. PMID 29286918.

- ^ Zöller M (January 2009). "Tetraspanins: push and pull in suppressing and promoting metastasis". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 9 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1038/nrc2543. PMID 19078974. S2CID 32065330.

- ^ Ventress JK, Partridge LJ, Read RC, Cozens D, MacNeil S, Monk PN (2016-07-28). "Peptides from Tetraspanin CD9 Are Potent Inhibitors of Staphylococcus Aureus Adherence to Keratinocytes". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0160387. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1160387V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160387. PMC 4965146. PMID 27467693.

- ^ Anzai N, Lee Y, Youn BS, Fukuda S, Kim YJ, Mantel C, et al. (June 2002). "C-kit associated with the transmembrane 4 superfamily proteins constitutes a functionally distinct subunit in human hematopoietic progenitors". Blood. 99 (12): 4413–21. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.12.4413. PMID 12036870.

- ^ a b Radford KJ, Thorne RF, Hersey P (May 1996). "CD63 associates with transmembrane 4 superfamily members, CD9 and CD81, and with beta 1 integrins in human melanoma". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 222 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1996.0690. PMID 8630057.

- ^ Mazzocca A, Carloni V, Sciammetta S, Cordella C, Pantaleo P, Caldini A, et al. (September 2002). "Expression of transmembrane 4 superfamily (TM4SF) proteins and their role in hepatic stellate cell motility and wound healing migration". Journal of Hepatology. 37 (3): 322–30. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00175-7. PMID 12175627.

- ^ Lozahic S, Christiansen D, Manié S, Gerlier D, Billard M, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E (March 2000). "CD46 (membrane cofactor protein) associates with multiple beta1 integrins and tetraspans". European Journal of Immunology. 30 (3): 900–7. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<900::AID-IMMU900>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 10741407.

- ^ Park KR, Inoue T, Ueda M, Hirano T, Higuchi T, Maeda M, et al. (March 2000). "CD9 is expressed on human endometrial epithelial cells in association with integrins alpha(6), alpha(3) and beta(1)". Molecular Human Reproduction. 6 (3): 252–7. doi:10.1093/molehr/6.3.252. PMID 10694273.

- ^ Hirano T, Higuchi T, Ueda M, Inoue T, Kataoka N, Maeda M, et al. (February 1999). "CD9 is expressed in extravillous trophoblasts in association with integrin alpha3 and integrin alpha5". Molecular Human Reproduction. 5 (2): 162–7. doi:10.1093/molehr/5.2.162. PMID 10065872.

- ^ Horváth G, Serru V, Clay D, Billard M, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E (November 1998). "CD19 is linked to the integrin-associated tetraspans CD9, CD81, and CD82". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (46): 30537–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.46.30537. PMID 9804823.

- ^ Charrin S, Le Naour F, Oualid M, Billard M, Faure G, Hanash SM, et al. (April 2001). "The major CD9 and CD81 molecular partner. Identification and characterization of the complexes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (17): 14329–37. doi:10.1074/jbc.M011297200. PMID 11278880.

- ^ Stipp CS, Orlicky D, Hemler ME (February 2001). "FPRP, a major, highly stoichiometric, highly specific CD81- and CD9-associated protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (7): 4853–62. doi:10.1074/jbc.M009859200. PMID 11087758.

- ^ Tachibana I, Bodorova J, Berditchevski F, Zutter MM, Hemler ME (November 1997). "NAG-2, a novel transmembrane-4 superfamily (TM4SF) protein that complexes with integrins and other TM4SF proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (46): 29181–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.46.29181. PMID 9360996.

- ^ Gutiérrez-López MD, Gilsanz A, Yáñez-Mó M, Ovalle S, Lafuente EM, Domínguez C, et al. (October 2011). "The sheddase activity of ADAM17/TACE is regulated by the tetraspanin CD9". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (19): 3275–92. doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0639-0. PMC 11115118. PMID 21365281. S2CID 23682577.

- ^ Gustafson-Wagner E, Stipp CS (2013). "The CD9/CD81 tetraspanin complex and tetraspanin CD151 regulate α3β1 integrin-dependent tumor cell behaviors by overlapping but distinct mechanisms". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e61834. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...861834G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061834. PMC 3629153. PMID 23613949.

Further reading

[edit]- Horejsí V, Vlcek C (August 1991). "Novel structurally distinct family of leucocyte surface glycoproteins including CD9, CD37, CD53 and CD63". FEBS Letters. 288 (1–2): 1–4. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)80988-F. PMID 1879540. S2CID 26316623.

- Berditchevski F (December 2001). "Complexes of tetraspanins with integrins: more than meets the eye". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 23): 4143–51. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.23.4143. PMID 11739647.

- Ninomiya H, Sims PJ (July 1992). "The human complement regulatory protein CD59 binds to the alpha-chain of C8 and to the "b"domain of C9". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (19): 13675–80. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42266-1. PMID 1377690.

- Miyake M, Koyama M, Seno M, Ikeyama S (December 1991). "Identification of the motility-related protein (MRP-1), recognized by monoclonal antibody M31-15, which inhibits cell motility". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 174 (6): 1347–54. doi:10.1084/jem.174.6.1347. PMC 2119050. PMID 1720807.

- Boucheix C, Benoit P, Frachet P, Billard M, Worthington RE, Gagnon J, Uzan G (January 1991). "Molecular cloning of the CD9 antigen. A new family of cell surface proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (1): 117–22. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)52410-8. PMID 1840589.

- Iwamoto R, Senoh H, Okada Y, Uchida T, Mekada E (October 1991). "An antibody that inhibits the binding of diphtheria toxin to cells revealed the association of a 27-kDa membrane protein with the diphtheria toxin receptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (30): 20463–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54947-4. PMID 1939101.

- Benoit P, Gross MS, Frachet P, Frézal J, Uzan G, Boucheix C, Nguyen VC (January 1991). "Assignment of the human CD9 gene to chromosome 12 (region P13) by use of human specific DNA probes". Human Genetics. 86 (3): 268–72. doi:10.1007/bf00202407. PMID 1997380. S2CID 27178985.

- Lanza F, Wolf D, Fox CF, Kieffer N, Seyer JM, Fried VA, et al. (June 1991). "cDNA cloning and expression of platelet p24/CD9. Evidence for a new family of multiple membrane-spanning proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (16): 10638–45. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99271-9. PMID 2037603.

- Higashihara M, Takahata K, Yatomi Y, Nakahara K, Kurokawa K (May 1990). "Purification and partial characterization of CD9 antigen of human platelets". FEBS Letters. 264 (2): 270–4. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80265-K. PMID 2358073. S2CID 42129059.

- Masellis-Smith A, Shaw AR (March 1994). "CD9-regulated adhesion. Anti-CD9 monoclonal antibody induce pre-B cell adhesion to bone marrow fibroblasts through de novo recognition of fibronectin". Journal of Immunology. 152 (6): 2768–77. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.152.6.2768. PMID 7511626. S2CID 23491895.

- Chalupny NJ, Kanner SB, Schieven GL, Wee SF, Gilliland LK, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA (July 1993). "Tyrosine phosphorylation of CD19 in pre-B and mature B cells". The EMBO Journal. 12 (7): 2691–6. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05930.x. PMC 413517. PMID 7687539.

- Rubinstein E, Benoit P, Billard M, Plaisance S, Prenant M, Uzan G, Boucheix C (April 1993). "Organization of the human CD9 gene". Genomics. 16 (1): 132–8. doi:10.1006/geno.1993.1150. PMID 8486348.

- Schmidt C, Künemund V, Wintergerst ES, Schmitz B, Schachner M (January 1996). "CD9 of mouse brain is implicated in neurite outgrowth and cell migration in vitro and is associated with the alpha 6/beta 1 integrin and the neural adhesion molecule L1". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 43 (1): 12–31. doi:10.1002/jnr.490430103. PMID 8838570. S2CID 84774340.

- Sincock PM, Mayrhofer G, Ashman LK (April 1997). "Localization of the transmembrane 4 superfamily (TM4SF) member PETA-3 (CD151) in normal human tissues: comparison with CD9, CD63, and alpha5beta1 integrin". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 45 (4): 515–25. doi:10.1177/002215549704500404. PMID 9111230.

- Rubinstein E, Poindessous-Jazat V, Le Naour F, Billard M, Boucheix C (August 1997). "CD9, but not other tetraspans, associates with the beta1 integrin precursor". European Journal of Immunology. 27 (8): 1919–27. doi:10.1002/eji.1830270815. PMID 9295027. S2CID 42866423.

- Cho, J.H., Kim, E., Son, Y. et al. (2020). CD9 induces cellular senescence and aggravates atherosclerotic plaque formation. Cell Death & Differentiation https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-0537-9

External links

[edit]- Human CD9 genome location and CD9 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.