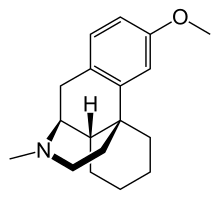

Dextromethorphan

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Robitussin, Delsym, DM, DexAlone, Duract |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682492 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Low |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (liver) enzymes: major CYP2D6, minor CYP3A4, and minor CYP3A5 |

| Elimination half-life | 2-4 hours (extensive metabolisers); 24 hours (poor metabolisers)[2] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.321 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H25NO |

| Molar mass | 271.40 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 111 °C (232 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Dextromethorphan (DXM or DM) is a drug of the morphinan class with sedative, dissociative, and stimulant properties (at higher doses). It is one of the active ingredients in many over-the-counter cold and cough medicines, including generic labels and store brands, Benylin DM, Mucinex DM, Camydex-20 tablets, Robitussin, NyQuil, Dimetapp, Vicks, Coricidin, Delsym, TheraFlu, Cheracol D, and others. Dextromethorphan has also found numerous other uses in medicine, ranging from pain relief (as either the primary analgesic, or an opioid potentiator) over psychological applications to the treatment of addiction. It is sold in syrup, tablet, spray, and lozenge forms. In its pure form, dextromethorphan occurs as a white powder.[3]

DXM is also used recreationally. When exceeding label-specified maximum dosages, dextromethorphan acts as a dissociative anesthetic. Its mechanism of action is via multiple effects, including actions as a nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitor[4] and a sigma-1 receptor agonist.[5][6] DXM and its major metabolite, dextrorphan, also act as an NMDA receptor antagonist at high doses, which produces effects similar to, yet distinct from, the dissociative states created by other dissociative anesthetics such as ketamine and phencyclidine. As well, the metabolite 3-methoxymorphinan of dextrorphan (thus a second-level metabolite of DXM) produces local anesthetic effects in rats with potency above dextrorphan, but below that of DXM.[7]

Medical use

Cough suppression

The primary use of dextromethorphan is as a cough suppressant, for the temporary relief of cough caused by minor throat and bronchial irritation (such as commonly accompanies the flu and common cold), as well as those resulting from inhaled particle irritants.[8]

Pseudobulbar affect and other neuropsychiatric disorders

In 2010, the FDA approved the combination product dextromethorphan/quinidine for the treatment of pseudobulbar affect (emotional lability).[9] The combination is also under investigation for the treatment of a variety of other neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions, such as agitation associated with Alzheimer's disease and major depressive disorder.[9] Dextromethorphan is the actual therapeutic agent in the combination; quinidine merely serves to inhibit the enzymatic degradation of dextromethorphan and thereby increase its circulating concentrations via inhibition of CYP2D6.[9]

Recreational use

Over-the-counter preparations containing dextromethorphan have been used in manners inconsistent with their labeling, often as a recreational drug.[10] At doses much higher than medically recommended, DXM and its major metabolite, dextrorphan, acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist, which produces effects similar to, yet distinct from, the dissociative hallucinogenic states created by other dissociative anaesthetics such as ketamine and phencyclidine.[11] It may produce distortions of the visual field - feelings of dissociation, distorted bodily perception, and excitement, as well as a loss of sense of time. Some users report stimulant-like euphoria, particularly in response to music. Dextromethorphan usually provides its recreational effects in a non-linear fashion, so that they are experienced in significantly varied stages. These stages are commonly referred to as "plateaus".[12] Teens tend to be at higher risk to use dextromethorphan related drugs as it is easier to access, and an easier way to cope with psychiatric disorders.[13]

Adverse effects

Side effects of dextromethorphan use can include:[2][8][14]

At normal doses:

- body rash/itching (see below)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Sedation

- Confusion

- Nervousness

- Closed-eye hallucination

Rare side effects include respiratory depression.[8] It is considered less addictive than the other common weak opiate cough suppressant, codeine.[2]

At doses three to 10 times the recommended therapeutic dose:[15]

- Euphoria

- Increased energy

- Increased confidence

- Mild nausea

- Restlessness

- Insomnia

- "Speeding"/talking fast

- Feelings of increased strength

- Enlarged pupils/glazed eyes (but not red)

At dosages 15 to 75 times the recommended therapeutic dose:[15]

- Hallucinations

- Dissociation

- Vomiting

- Blurred vision and/or double vision

- Bloodshot eyes

- Dilated pupils

- Sweating

- Fever

- Bruxia

- Hypotension

- Hypertension

- Tachycardia

- Shallow respiration

- Diarrhea

- Urinary retention

- Muscle spasms

- Sedation

- Euphoria

- Paresthesia

- Blackouts

- Sight loss

- Inability to focus eyes

- Skin rash

Dextromethorphan can also cause other gastrointestinal disturbances. It had been thought to cause Olney's lesions when administered intravenously; however, this was later proven inconclusive, due to lack of research on humans. Tests were performed on rats, giving them 50 mg and up every day up to a month. Neurotoxic changes, including vacuolation, have been observed in posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices of rats administered other NMDA antagonists such as PCP, but not with dextromethorphan.[16][17] In many documented cases, dextromethorphan has produced psychological dependence in people who used it recreationally. However, it does not produce physical addiction, according to the WHO Committee on Drug Dependence.[18] Though since dextromethorphan also acts as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) users describe that regular recreational use over a longer period of time can cause withdrawal symptoms that are similar to those of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Additionally, disturbances have been reported in: sleep, senses, movement, mood, and thinking.

Contraindications

Because dextromethorphan can trigger a histamine release (allergic reaction), atopic children, who are especially susceptible to allergic reactions, should be administered dextromethorphan only if absolutely necessary, and only under the strict supervision of a healthcare professional.[14]

Drug interactions

Dextromethorphan should not be taken with monoamine oxidase inhibitors[14] due to the potential for serotonin syndrome, which is a potentially life-threatening condition that can occur rapidly, due to a buildup of an excessive amount of serotonin in the body. Dextromethorphan can also cause serotonin syndrome when used with SSRI medicines, an interaction which has been documented in clinical cases where dextromethorphan is taken at recreational doses. The link between therapeutic dosages of dextromethorphan and serotonin syndrome has been suggested to be less conclusive.[4]

Food interactions

Caution should be exercised when taking dextromethorphan when drinking grapefruit juice or eating grapefruits, as compounds in grapefruit affect a number of drugs, including dextromethorphan, through the inhibition of the cytochrome p450 system in the liver, and can lead to excessive accumulation and prolonged effects. Grapefruit and grapefruit juices (especially white grapefruit juice, but also including other citrus fruits such as bergamot and lime, as well as a number of noncitrus fruits[19]) generally are recommended to be avoided while using dextromethorphan and numerous other medications.

Laboratory testing

Testing for this drug is done either by blood or by urine. Blood can be either serum or plasma. Urine requires only 2 ml minimum.

Chemistry

Dextromethorphan is the dextrorotatory enantiomer of levomethorphan, which is the methyl ether of levorphanol, both opioid analgesics. It is named according to IUPAC rules as (+)-3-methoxy-17-methyl-9α,13α,14α-morphinan. As its pure form, dextromethorphan occurs as an odorless, opalescent white powder. It is freely soluble in chloroform and insoluble in water; the hydrobromide salt is water-soluble up to 1.5g/100 mL at 25 °C.[20] Dextromethorphan is commonly available as the monohydrated hydrobromide salt, however some newer extended-release formulations contain dextromethorphan bound to an ion-exchange resin based on polystyrene sulfonic acid. Dextromethorphan's specific rotation in water is +27.6° (20 °C, Sodium D-line).[citation needed]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Dextromethorphan has been shown to possess the following properties, mainly in binding assays to various receptors of animal tissues. Low Ki values mean strong binding or high affinity; high Ki values mean weak binding to the target or low affinity:

- Uncompetitive NMDA receptor (PCP site) antagonist (Ki = 7,253 nM).[21]

- σ1 (Ki = 150 nM) and σ2 sigma receptor (Ki = 11,060 nM) agonist.[21]

- α3β4-, α4β2-, and α7-nACh receptor (Ki = in the μM range) antagonist. Dextromethorphan binds to nicotinic receptors in frog eggs (Xenopus oocytes), human embryonic kidney cells and mouse tissue. It inhibits the antinociceptive (pain killing) action of nicotine in the tail-flick test in mice, where mouse tails are exposed to heat, which makes the mouse flick its tail if it feels pain.[22][23][24]

- μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptor agonist (Ki = 1,280 nM, 11,500 nM, and 7,000 nM, respectively)[25]

- SERT and NET inhibitor (Ki = 23 nM and 240 nM, respectively)[4][25][26][27]

- NADPH oxidase inhibitor.[28]

- Nav1.2 channel blocker[29]

Its affinities for some of the sites listed are relatively very low and are probably insignificant, such as binding to NMDA receptors and opioid receptors, even at high recreational doses.[citation needed] Instead of acting as a direct antagonist of the NMDA receptor itself, dextromethorphan likely functions as a prodrug to its nearly 10-fold more potent metabolite dextrorphan, and this is the true mediator of its dissociative effects.[30] What role, if any, (+)-3-methoxymorphinan, dextromethorphan's other major metabolite, plays in its effects is not entirely clear.[31]

Pharmacokinetics

Following oral administration, dextromethorphan is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, where it enters the bloodstream and crosses the blood–brain barrier.[citation needed]

At therapeutic doses, dextromethorphan acts centrally (meaning that it acts on the brain) as opposed to locally (on the respiratory tract). It elevates the threshold for coughing, without inhibiting ciliary activity. Dextromethorphan is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and converted into the active metabolite dextrorphan in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6. The average dose necessary for effective antitussive therapy is between 10 and 45 mg, depending on the individual. The International Society for the Study of Cough recommends "an adequate first dose of medication is 60 mg in the adult and repeat dosing should be infrequent rather than the qds recommended."[32]

The duration of action after oral administration is about three to eight hours for dextromethorphan-hydrobromide, and 10 to 12 hours for dextromethorphan-polistirex. Around one in 10 of the Caucasian population has little or no CYP2D6 enzyme activity, leading to long-lived high drug levels.[32]

Metabolism

The first pass through the hepatic portal vein results in some of the drug being metabolized by O-demethylation into an active metabolite of dextromethorphan called dextrorphan (DXO). DXO is the 3-hydroxy derivative of dextromethorphan. The therapeutic activity of dextromethorphan is believed to be caused by both the drug and this metabolite. Dextromethorphan also undergoes N-demethylation (to 3-methoxymorphinan or MEM),[33] and partial conjugation with glucuronic acid and sulfate ions. Hours after dextromethorphan therapy, (in humans) the metabolites (+)-3-hydroxy-N-methylmorphinan, (+)-3-morphinan, and traces of the unchanged drug are detectable in the urine.[14]

A major metabolic catalyst involved is the cytochrome P450 enzyme known as 2D6, or CYP2D6. A significant portion of the population has a functional deficiency in this enzyme and are known as poor CYP2D6 metabolizers. O-demethylation of DXM to DXO contributes to at least 80% of the DXO formed during DXM metabolism.[33] As CYP2D6 is a major metabolic pathway in the inactivation of dextromethorphan, the duration of action and effects of dextromethorphan can be increased by as much as three times in such poor metabolizers.[34] In one study on 252 Americans, 84.3% were found to be "fast" (extensive) metabolizers, 6.8% to be "intermediate" metabolizers, and 8.8% were "slow" metabolizers of DXM.[35] A number of alleles for CYP2D6 are known, including several completely inactive variants. The distribution of alleles is uneven amongst ethnic groups.

A large number of medications are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6. Some types of medications known to inhibit CYP2D6 include certain SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, some antipsychotics, and the commonly available antihistamine diphenhydramine. Therefore, the potential of interactions exists between dextromethorphan and medications that inhibit this enzyme, particularly in slow metabolizers.[citation needed] DXM is also metabolized by CYP3A4. N-demethylation is primarily accomplished by CYP3A4, contributing to at least 90% of the MEM formed as a primary metabolite of DXM.[33]

A number of other CYP enzymes are implicated as minor pathways of DXM metabolism. CYP2B6 is actually more effective than CYP3A4 at N-demethylation of DXM, but, since the average individual has a much lower CYP2B6 content in his/her liver relative to CYP3A4, most N-demethylation of DXM is catalyzed by CYP3A4.[33]

History

The racemic parent compound racemorphan was first described in a Swiss and US patent application from Hoffmann-La Roche in 1946 and 1947, respectively; a patent was granted in 1950.[36] A resolution of the two isomers of racemorphan with tartaric acid was published in 1952,[36] and DXM was successfully tested in 1954 as part of US Navy and CIA-funded research on nonaddictive substitutes for codeine.[37] DXM was approved by the FDA in 1958 as an over-the-counter antitussive.[36] As had been initially hoped, DXM was a solution for some of the problems associated with the use of codeine phosphate as a cough suppressant, such as sedation and opiate dependence, but like the dissociative anesthetics phencyclidine and ketamine, DXM later became associated with nonmedical use.[10][36]

During the 1960s and 1970s, dextromethorphan became available in an over-the-counter tablet form by the brand name Romilar. In 1973, Romilar was taken off the shelves after a burst in sales because of frequent misuse, and was replaced by cough syrup in an attempt to cut down on abuse.[10] The advent of widespread internet access in the 1990s allowed users to rapidly disseminate information about DXM, and online discussion groups formed around use and acquisition of the drug.[36] As early as 1996, DXM HBr powder could be purchased in bulk from online retailers, allowing users to avoid consuming DXM in syrup preparations.[36] As of January 1, 2012, dextromethorphan is prohibited for sale to minors in the state of California, except with a doctor's prescription.[38]

In Indonesia, the National Agency of Drug and Food Control (BPOM-RI) prohibited single-component dextromethorphan drug sales with or without prescription. Indonesia is the only country in the world that makes single-component dextromethorphan illegal even by prescription[39] and violators may be prosecuted by law. Indonesian National Narcotic Bureau (BNN RI) has even threatened to revoke pharmacies' and drug stores' licenses if they still stock dextromethorphan, and will notify the police for criminal prosecution.[40] As a result of this regulation, 130 drugs have been withdrawn from the market, but drugs containing multicomponent dextromethorphan can be sold over the counter.[41] In its official press release, BPOM-RI also stated that dextromethorphan is often used as a substitute for marijuana, amphetamine, and heroin by drug abusers, and its use as an antitussive is less beneficial nowadays[42]

The Director of Narcotics, Psychotropics, and Addictive Substances Control (NAPZA) BPOM-RI, Dr. Danardi Sosrosumihardjo, SpKJ, explains that dextromethorphan, morphine, and heroin are derived from the same tree, and states the effect of dextromethorphan to be equivalent to 1/100 of morphine and injected heroin.[43] By contrast, the Deputy of Therapeutic Product and NAPZA Supervision BPOM-RI, Dra. Antonia Retno Tyas Utami, Apt. MEpid., states that dextromethorphan, being chemically similar to morphine, has a much more dangerous and direct effect to the central nervous system, thus causing mental breakdown in the user. She also claimed, without citing any prior scientific study or review, that unlike morphine users, dextromethorphan users cannot be rehabilitated.[44] This claim is contradicted by numerous scientific studies which show that naloxone alone offers effective treatment and promising therapy results in treating dextromethorphan addiction and poisoning.[45][46][47] Dra. Antonia Retno Tyas Utami also claimed high rates of dextromethorphan abuse, including fatalities, in Indonesia and to be further put in question suggest that codeine, despite being a more physically addictive µ-opioid class antitussive, be made available as an alternative to dextromethorphan.[48]

See also

- Antitussive

- Cough syrup

- Psychedelics

- Dissociatives

- Morphinans

- (+)-Naloxone - another dextrorotatory enantiomer of an opioid drug with useful nonopioid effects

References

- ^ Kukanich, B.; Papich, M. G. (2004). "Plasma profile and pharmacokinetics of dextromethorphan after intravenous and oral administration in healthy dogs". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 27 (5): 337–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2004.00608.x. PMID 15500572.

- ^ a b c "Balminil DM, Benylin DM (dextromethorphan) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Reference Tables: Description and Solubility - D". Retrieved 2011-05-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Schwartz, Anna R.; Pizon, Anthony F.; Brooks, Daniel E. (2008). "Dextromethorphan-induced serotonin syndrome". Clinical Toxicology. 46 (8): 771–3. doi:10.1080/15563650701668625. PMID 19238739.

- ^ Shin, E; Nah, S; Chae, J; Bing, G; Shin, S; Yen, T; Baek, I; Kim, W; Maurice, T; Nabeshima, T; Kim, H. C. (2007). "Dextromethorphan attenuates trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity via σ1 receptor activation in rats". Neurochemistry International. 50 (6): 791–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2007.01.008. PMID 17386960.

- ^ Shin, Eun-Joo; Nah, Seung-Yeol; Kim, Won-Ki; Ko, Kwang Ho; Jhoo, Wang-Kee; Lim, Yong-Kwang; Cha, Joo Young; Chen, Chieh-Fu; Kim, Hyoung-Chun (2005). "The dextromethorphan analog dimemorfan attenuates kainate-induced seizuresvia σ1receptor activation: Comparison with the effects of dextromethorphan". British Journal of Pharmacology. 144 (7): 908–18. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705998. PMC 1576070. PMID 15723099.

- ^ Hou, Chia-Hui; Tzeng, Jann-Inn; Chen, Yu-Wen; Lin, Ching-Nan; Lin, Mao-Tsun; Tu, Chieh-Hsien; Wang, Jhi-Joung (2006). "Dextromethorphan, 3-methoxymorphinan, and dextrorphan have local anaesthetic effect on sciatic nerve blockade in rats". European Journal of Pharmacology. 544 (1–3): 10–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.013. PMID 16844109.

- ^ a b c Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Nguyen, Linda; Thomas, Kelan L.; Lucke-Wold, Brandon P.; Cavendish, John Z.; Crowe, Molly S.; Matsumoto, Rae R. (2016). "Dextromethorphan: An update on its utility for neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 159: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.01.016. ISSN 0163-7258.

- ^ a b c "Dextromethorphan (DXM)". Cesar.umd.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- ^ "Dextromethorphan" (PDF). Drugs and Chemicals of Concern. Drug Enforcement Administration. August 2010.

- ^ Giannini AJ (1997). Drugs of abuse (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Practice Management Information Corp. ISBN 1570660530.[page needed]

- ^ Ackerman, Sarah C. (2010). ""Dextromethorphan Abuse and Dependence In Adolescents."". Journal of Dual Diagnosis.

- ^ a b c d "Dextromethorphan". NHTSA.

- ^ a b "Teen Drug Abuse: Cough Medicine and DXM (Dextromethorphan)". webmd.

- ^ Olney, J.; Labruyere, J; Price, M. (1989). "Pathological changes induced in cerebrocortical neurons by phencyclidine and related drugs". Science. 244 (4910): 1360–2. Bibcode:1989Sci...244.1360O. doi:10.1126/science.2660263. PMID 2660263.

- ^ Carliss, R.D.; Radovsky, A.; Chengelis, C.P.; o’Neill, T.P.; Shuey, D.L. (2007). "Oral administration of dextromethorphan does not produce neuronal vacuolation in the rat brain". NeuroToxicology. 28 (4): 813–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.03.009. PMID 17573115.

- ^ WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Seventeenth Report (PDF). World Health Organization. 1970. Retrieved 2008-12-29.[page needed]

- ^ "Inhibitors of CYP3A4". ganfyd.org. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/pim179.htm

- ^ a b Boyer, Edward; Burns, Jarrett (2013). "Antitussives and substance abuse". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 4: 75–82. doi:10.2147/SAR.S36761. PMC 3931656. PMID 24648790.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Damaj, M. I.; Flood, P; Ho, K. K.; May, E. L.; Martin, B. R. (2004). "Effect of Dextrometorphan and Dextrorphan on Nicotine and Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors: In Vitro and in Vivo Selectivity". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 312 (2): 780–5. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.075093. PMID 15356218.

- ^ Lee, Jun-Ho; Shin, Eun-Joo; Jeong, Sang Min; Kim, Jong-Hoon; Lee, Byung-Hwan; Yoon, In-Soo; Lee, Joon-Hee; Choi, Sun-Hye; Lee, Sang-Mok; Lee, Phil Ho; Kim, Hyoung-Chun; Nah, Seung-Yeol (2006). "Effects of dextrorotatory morphinans on α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". European Journal of Pharmacology. 536 (1–2): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.034. PMID 16563374.

- ^ Hernandez, S. C.; Bertolino, M; Xiao, Y; Pringle, K. E.; Caruso, F. S.; Kellar, K. J. (2000). "Dextromethorphan and Its Metabolite Dextrorphan Block α3β4 Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 293 (3): 962–7. PMID 10869398.

- ^ a b Codd, E. E.; Shank, R. P.; Schupsky, J. J.; Raffa, R. B. (1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: Structural determinants and role in antinociception". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 274 (3): 1263–70. PMID 7562497.

- ^ Henderson, Mark G.; Fuller, Ray W. (1992). "Dextromethorphan antagonizes the acute depletion of brain serotonin by p-chloroamphetamine and H75/12 in rats". Brain Research. 594 (2): 323–6. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(92)91144-4. PMID 1280529.

- ^ Gillman, P. K. (2005). "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 95 (4): 434–41. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210. PMID 16051647.

- ^ Zhang, W.; Wang, T; Qin, L; Gao, H. M.; Wilson, B; Ali, S. F.; Zhang, W; Hong, J. S.; Liu, B (2004). "Neuroprotective effect of dextromethorphan in the MPTP Parkinson's disease model: Role of NADPH oxidase". The FASEB Journal. 18 (3): 589–91. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0983fje. PMID 14734632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Obukhov, Alexander G.; Gao, Xiao-Fei; Yao, Jin-Jing; He, Yan-Lin; Hu, Changlong; Mei, Yan-Ai (2012). "Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists Directly Inhibit NaV1.2/1.4 Channels". PLoS ONE. 7 (11): e49384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049384. ISSN 1932-6203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chou, Yueh-Ching; Liao, Jyh-Fei; Chang, Wan-Ya; Lin, Ming-Fang; Chen, Chieh-Fu (1999). "Binding of dimemorfan to sigma-1 receptor and its anticonvulsant and locomotor effects in mice, compared with dextromethorphan and dextrorphan". Brain Research. 821 (2): 516–9. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01125-7. PMID 10064839.

- ^ Schmider, Jürgen; Greenblatt, David J.; Fogelman, Steven M.; von Moltke, Lisa L.; Shader, Richard I. (1997). "Metabolism of Dextromethorphanin vitro: Involvement of Cytochromes P450 2D6 AND 3A3/4, with a Possible Role of 2E1". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 18 (3): 227–40. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-081X(199704)18:3<227::AID-BDD18>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 9113345.

- ^ a b Morice AH. "Cough". International Society for the Study of Cough.

- ^ a b c d Yu, A; Haining, R. L. (2001). "Comparative contribution to dextromethorphan metabolism by cytochrome P450 isoforms in vitro: Can dextromethorphan be used as a dual probe for both CTP2D6 and CYP3A activities?". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 29 (11): 1514–20. PMID 11602530.

- ^ Capon, Deborah A.; Bochner, Felix; Kerry, Nicole; Mikus, Gerd; Danz, Catherine; Somogyi, Andrew A. (1996). "The influence of CYP2D6 polymorphism and quinidine on the disposition and antitussive effect of dextromethorphan in humans". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 60 (3): 295–307. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90056-9. PMID 8841152.

- ^ Woodworth, J. R.; Dennis, S. R. K.; Moore, L.; Rotenberg, K. S. (1987). "The Polymorphic Metabolism of Dextromethorphan". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (2): 139–43. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb02174.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Morris, Hamilton; Wallach, Jason (2014). "From PCP to MXE: A comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ "Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- ^ "Senate Bill No. 514" (PDF). An act to add Sections 11110 and 11111 to the Health and Safety Code, relating to nonprescription drugs. State of California, Legislative Counsel.

- ^ http://nasional.news.viva.co.id/news/read/506418-bpom-tetap-batalkan-izin-edar-obat-dekstrometorfan[full citation needed]

- ^ http://daerah.sindonews.com/read/878465/21/bnn-ancam-tutup-apotek-penjual-dextromethorphan-1404129585[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.pom.go.id/files/edaran_dektrome_2013.pdf[full citation needed]

- ^ http://www.pom.go.id/new/index.php/view/pers/231/Penjelasan-Terkait-Produk-Obat-Batuk-yang-Beredar--dan--Mengandung-Bahan-Dekstrometorfan-Tunggal-.html[full citation needed]

- ^ http://health.liputan6.com/read/2058886/ini-alasan-130-obat-batuk-ditarik-dari-pasaran[full citation needed]

- ^ http://health.liputan6.com/read/708598/dibanding-morfin-obat-batuk-berdekstro-lebih-mematikan[full citation needed]

- ^ Schneider, Sandra M.; Michelson, Edward A.; Boucek, Charles D.; Ilkhanipour, Kaveh (1991). "Dextromethorphan poisoning reversed by naloxone". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (3): 237–8. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(91)90085-X. PMID 2018593.

- ^ Shaul, W. L.; Wandell, M; Robertson, W. O. (1977). "Dextromethorphan toxicity: Reversal by naloxone". Pediatrics. 59 (1): 117–8. PMID 840529.

- ^ Manning, Barton H.; Mao, Jianren; Frenk, Hanan; Price, Donald D.; Mayer, David J. (1996). "Continuous co-administration of dextromethorphan or MK-801 with morphine: Attenuation of morphine dependence and naloxone-reversible attenuation of morphine tolerance". Pain. 67 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(96)81972-5. PMID 8895234.

- ^ http://health.kompas.com/read/2013/10/01/1618072/BPOM.akan.Tarik.Pil.Dekstro[full citation needed]