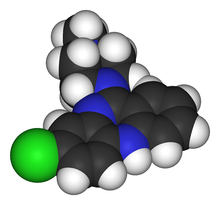

Clozapine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Clozaril |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691001 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60 to 70% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, by several CYP isozymes |

| Elimination half-life | 6 to 26 hours (mean value 14.2 hours in steady state conditions) |

| Excretion | 80% in metabolized state: 30% biliary and 50% renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.831 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H19ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 326.823 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 183 °C (361 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 0.1889[2] mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clozapine (sold as Clozaril, Azaleptin, Leponex, Fazaclo, Froidir; Denzapine, Zaponex in the UK; Klozapol in Poland, Clopine in Australia and New Zealand) is an antipsychotic medication used in the treatment of schizophrenia, and is also used off-label in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Wyatt. R and Chew. R (2005) tells us there are three pharmaceutical companies that market this drug at present: Novartis Pharmaceuticals (manufacturer), Mylan Laboratories and Ivax Pharmaceuticals (market generic clozapine). The first of the atypical antipsychotics to be developed, it was first introduced in Europe in 1971, but was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer in 1975 after it was shown to cause agranulocytosis, a condition involving a dangerous decrease in the number of white blood cells, that led to death in some patients. In 1989, after studies demonstrated that it was more effective than any other antipsychotic for treating schizophrenia[citation needed], the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved clozapine's use but only for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. The FDA requires blood testing for patients taking clozapine.[3][4] The FDA also requires clozapine to carry five black box warnings for agranulocytosis, seizures, myocarditis, for "other adverse cardiovascular and respiratory effects", and for "increased mortality in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis."[5] In 2002 the FDA approved clozapine for reducing the risk of suicidal behavior for patients with schizophrenia.

Clozapine is usually used as a last resort in patients that have not responded to other anti-psychotic treatments due to its danger of causing agranulocytosis as well as the costs of having to have blood tests continually during treatment. It is, however, one of the very effective anti-psychotic treatment choices.[6] Patients are monitored weekly for the first six months. If there are no low counts the patient can be monitored every two weeks for an additional six months. Afterwards, the patient may qualify for every four week monitoring.[7] Clozapine has numerous severe side effects including agranulocytosis, bowel infarction[8], seizures[9], myocarditis, and diabetes. Additionally, it also often causes less serious side effects such as sialorrhea and weight gain.

Medical uses

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug primarily prescribed to patients who are unresponsive to or intolerant of conventional neuroleptics.[10] It is used principally in treating treatment-resistant schizophrenia,[11] a term used for the failure of symptoms to respond satisfactorily to at least two different antipsychotics;[12] It clearly has been shown to be more effective in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia than the older typical antipsychotics[citation needed], with maximal effects in those who have responded poorly to other medication[citation needed]; though the relapse rate is lower and patient acceptability better[citation needed], this has not translated to significant observed benefits in global functioning.[11] There is some evidence clozapine may reduce propensity for substance abuse in schizophrenic patients.[13]

It is also used for reducing the risk of suicide in patients judged to belong to a high-risk group with chronic risk for suicidal behavior[citation needed]. Clozapine was shown to prolong the time to suicidal attempt significantly greater than olanzapine[citation needed].

Clozapine works well against positive (e.g., delusions, hallucinations) and negative (e.g. emotional and social withdrawal) symptoms of schizophrenia[citation needed]. It has no dyscognitive effect often seen with other psychoactive drugs and is even able to increase the capabilities of the patient to react to this environment and thereby fosters social rehabilitation[citation needed]. There has been one case report of successful use of Clozapine in isolated increase in Creatine Kinase (in absence of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome) in a patient with Schizophrenia where other atypical antipsychotics were not successful.[14]

Adverse effects

The use of clozapine is associated with side effects, many of which are minor, though some are serious and potentially fatal: the more common include extreme constipation, night-time drooling, muscle stiffness, sedation, tremors, orthostasis, hyperglycemia, and weight gain. The risks of extrapyramidal symptoms such as tardive dyskinesia are much less with clozapine when compared to the typical antipsychotics; this may be due to clozapine's anticholinergic effects. Extrapyramidal symptoms may subside somewhat after a person switches from another antipsychotic to clozapine.[15]

Clozapine also carries eleven black box warnings for agranulocytosis, CNS depression, leukopenia, neutropenia, seizure disorder, bone marrow suppression, dementia, hypotension, myocarditis, orthostatic hypotension and seizures.[16] Lowering of the seizure threshold may be dose related and slow initial titration of dose may decrease the risk for precipitating seizures. Slow titration of dosing may also decrease the risk for orthostatic hypotension and other adverse cardiovascular side effects.

Clozapine may have a synergistic effect with the sedating action of other drugs such as benzodiazepines, and thus respiratory depression may result with concomitant use. Care should be taken, especially if the latter drugs are given parenterally.

Many male patients have experienced ceasure of ejaculation during orgasm as a side effect of clozapine, though this is not documented in official drug guides [17]

Agranulocytosis

Clozapine carries a black box warning for drug-induced agranulocytosis. Without monitoring, agranulocytosis occurs in about 1% of patients who take clozapine during the first few months of treatment;[18] the risk of developing it is highest about three months into treatment, and decreases substantially thereafter, to less than 0.01% after one year.[19] Patients who have experienced agranulocytosis with previous treatment of clozapine should not receive it again.

In 2007, a pharmacogenetic test was introduced to measure the probability of developing agranulocytosis. The test has two gradations—Higher and Lower risk, with a relative agranulocytosis risk of 2.5 and 0.5 compared to general level. The company states that the test is based on two SNPs of the HLA-DQB1 gene.

Patients taking clozapine are required to have a blood cell count every week, for the first six months of therapy (in the USA) and for the first 18 weeks (in the UK). After this, they are required to have a blood cell count every other week for the second six months after therapy. After twelve months, blood cell counts need be performed every four weeks. Patients are advised to inform their doctor if they develop a sore throat, or fever. If the number of white blood-cells drops notably then referral to a hematologist is undertaken. The manufacturers of both the brand and generic clozapine are required by the FDA to track white blood cells counts for patients receiving clozapine, and pharmacies are required to obtain a copy of the CBC prior to dispensing the medication to the patient. The purpose of the monitoring system is to prevent rechallenge with clozapine in patients with a history of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis and to detect leukopenic events among patients taking clozapine. In other countries (e.g. in Europe), restrictions have been eased.

It has been suggested that coadministration of clozapine with an antioxidant such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid) can reduce the risk of agranulocytosis.[20]

Cardiac toxicity

A more recently identified and sometimes fatal side effect is that of myocarditis, which usually develops within the first month of commencement and presents with signs of cardiac failure and cardiac arrhythmias.[21] Cardiomyopathy is another potentially fatal cardiac condition that may arise less acutely. More recently, a regular six-monthly echocardiogram is also recommended to detect myocarditis.

Gastrointestinal hypomotility

Another underrecognized and potentially life-threatening side effect spectrum is gastrointestinal hypomotility, which may manifest as severe constipation, fecal impaction, paralytic ileus, bowel obstruction, acute megacolon, ischemia or necrosis. Monitoring of bowel function is recommended, as untreated cases are occasionally fatal.[22]

Hypersalivation

Hypersalivation (drooling or 'wet pillow syndrome') is seen in up to 30% of patients on clozapine.While clozapine is a muscarinic antagonist at the M1, M2, M3, and M5 receptors, clozapine is a full agonist at the M4 subset. Because M4 is highly expressed in the salivary gland, its M4 agonist activity is thought to be responsible for the hypersalivaiton.[23]

Central Nervous System

Central Nervous System side effects include drowsiness, vertigo, headache, tremor, syncope, sleep disturbances, nightmares, restlessness, akinesia, agitation, seizures, rigidity, akathisia, confusion, fatigue, insomnia, hyperkinesia, weakness, lethargy, ataxia, slurred speech, depression, myoclonic jerks, and anxiety. Rarely seen are delusions, hallucinations, delirium, amnesia, libido increase or decrease, paranoia and irritability, abnormal EEG, worsening of psychosis, paresthesia, status epilepticus, and obsessive compulsive symptoms.Similar to other antipsychotics Clozapine rarely has been known to cause Neuroleptic Malignant syndrome. [24]

Withdrawal effects

Abrupt withdrawal may lead to cholinergic rebound effects, severe movement disorders as well as severe psychotic decompensation. It has been recommended that patients, families, and caregivers are aware of the symptoms and risks of abrupt withdrawal of clozapine. When discontinuing clozapine, gradual dose reduction is recommended to reduce the intensity of withdrawal effects.[25][26]

Weight gain and diabetes

The FDA requires the manufacturers of all atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes with these medications. Indeed, there are case reports of clozapine-induced hyperglycemia and diabetes. In addition, there are also case reports of clozapine-induced diabetic ketoacidosis. There is data showing that clozapine can decrease insulin sensitivity. Clozapine should be used with caution in patients who are diagnosed with diabetes or in patients at risk for developing diabetes. All patients receiving clozapine should have their fasting blood glucose monitored.

In addition to hyperglycemia, significant weight gain is frequently experienced by patients treated with clozapine.[27] Impaired glucose metabolism and obesity have been shown to be constituents of the metabolic syndrome and may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. The data suggest that clozapine may be more likely to cause adverse metabolic effects than some of the other atypical antipsychotics.[28] A study has established that olanzapine and clozapine disturb the metabolism by making the body take preferentially its energy from fat (instead of privileging carbohydrates). Levels of carbohydrates remaining high, the body develops insulin resistance (causing diabetes).[29]

Research has indicated that clozapine may cause a deficiency of selenium.[30]

Contraindications

Clozapine is contraindicated in individuals with uncontrolled epilepsy, myeloproliferative disease, or agranulocytosis with prior clozapine treatment.

Many other (relative) contraindications (e.g. preexisting cardiovascular or liver damage, epilepsy) also exist.

Interactions

Fluvoxamine inhibits the metabolism of clozapine leading to significantly increased blood levels of clozapine.[31]

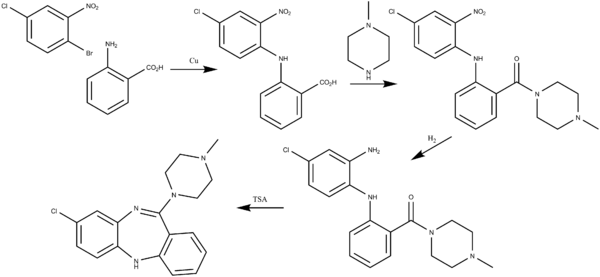

Chemistry

Clozapine is a dibenzodiazepine, that is structurally related to loxapine. It is slightly soluble in water, soluble in acetone, and very soluble in chloroform. Its solubility in water is 188.9 mg/L (25 C).[2] The manufacturer Novartis claim a solubility of <0.01% in water.[32]

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500618, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1002/hlca.19670500618instead. - S.A.A. Wander, FR 1334944 (1963).

- F. Hunziker, J. Schmutz, U.S. patent 3,539,573 (1970).

- S.A.A. Wander, GB 980853 (1961).

Mechanism of action

Clozapine is classified as an atypical antipsychotic drug because its profile of binding to serotonergic as well as dopamine receptors;[33] its effects on various dopamine mediated behaviors also differ from those exhibited by more typical antipsychotics. In particular, clozapine interferes to a lower extent with the binding of dopamine at D1, D2, D3 and D5 receptors, and has a high affinity for the D4 receptor, but it does not induce catalepsy nor inhibit apomorphine-induced stereotypy in animal models as is seen with 'conventional' neuroleptics. This evidence suggests clozapine is preferentially more active at limbic than at striatal dopamine receptors and may explain the relative freedom of clozapine from extrapyramidal side effects together with strong anticholinergic activity.

Several metabolites of Clozapine exhibit binding profiles similar to Clozapine. N-Desmethylclozapine may contribute significantly to the atypical effects of Clozapine treatment. N-desmethylclozapine acts as an agonist and/or partial agonist at D2, D3, δ-opioid, M1, M2, M3, M4, M5 receptors, and an antagonist/inverse agonist at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors.

Clozapine is also a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor, putatively improving depression, anxiety, and the negative cognitive symptoms. </ref>[2]</ref>

Clozapine also is a strong antagonist at different subtypes of adrenergic, cholinergic and histaminergic receptors, the last two being predominantly responsible for its side effect profile.

It has approximately the same potency as chlorpromazine.[clarification needed]

Pharmacokinetics

The absorption of clozapine is almost complete, but the oral bioavailability is only 60 to 70% due to first-pass metabolism. The time to peak concentration after oral dosing is about 2.5 hours, and food does not appear to affect the bioavailability of clozapine. The elimination half-life of clozapine is about 14 hours at steady state conditions (varying with daily dose).

Clozapine is extensively metabolized in the liver, via the cytochrome P450 system, to polar metabolites suitable for elimination in the urine and faeces. The major metabolite, norclozapine (desmethyl-clozapine), is pharmacologically active. The cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 1A2 is primarily responsible for clozapine metabolism, but 2C, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A3/4 appear to play roles as well. Agents that induce (e.g., cigarette smoke) or inhibit (e.g., theophylline, ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamine) CYP1A2 may increase or decrease, respectively, the metabolism of clozapine. For example, the induction of metabolism caused by smoking means that smokers require up to double the dose of clozapine compared with non-smokers to achieve an equivalent plasma concentration.[34]

Clozapine and norclozapine plasma levels may also be monitored, though they show a significant degree of variation and are higher in women and increase with age.[35] Monitoring of plasma levels of clozapine and norclozapine has been shown to be useful in assessment of compliance, metabolic status, prevention of toxicity, and in dose optimization.[34]

Dosage

Due to risk of serious side effects, clozapine treatment is commenced at a very low dose usually 12.5 mg once or twice on the first day[36] and increased slowly until a therapeutic dose is reached.[37][38] In severely ill and/or younger patients higher doses may be needed[citation needed], while in the elderly much lower doses may be sufficient[citation needed]. Once the patient is stabilized and the maintenance dose has been determined, the greater part or all of the daily dose may be given at bedtime.[38] This will ameliorate daytime sedation and orthostatic problems; most people benefit from the sedation to get to sleep anyway[citation needed]. Furthermore, compliance on medication taken more frequently than once daily drops off dramatically.[citation needed]

Norclozapine, the primary metabolite of clozapine, which accumulates to, on average, 70% or so of the clozapine concentration in plasma at steady-state (their sample, i.e., pre-dose, ideally in the morning). However, there is substantial variation in the clozapine:norclozapine concentration ratio between individuals.

A steady-state plasma clozapine concentration of 0.35 to 0.6 mg/L (N.B.: quoted values may vary slightly) should produce a clinical response in most patients.

History

Clozapine was developed by Sandoz in 1961, and trials took place in 1972, when it was released in Switzerland and Austria as Leponex. Two years later it was released in West Germany, and Finland in 1975. Early testing was performed in the United States around the same time.[39] In 1975, after reports of agranulocytosis leading to death in some clozapine-treated patients, clozapine was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer.[40] Clozapine fell out of favor for more than a decade. However, when studies demonstrated that clozapine was more effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia than other antipsychotics, the FDA and health authorities in most other countries approved its use only for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and required regular hematological monitoring to detect granulocytopenia, before agranulocytosis develops. In December 2002, clozapine was also approved for reducing the risk of suicide in schizophrenic or schizoaffective patients judged to be at chronic risk for suicidal behavior. In 2005 FDA approved criteria to allow reduced blood monitoring frequency.[41]

See also

Notes

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b Hopfinger A, Esposito EX, Llinas A, Glen RC, Goodman JM.. Findings of the Challenge To Predict Aqueous Solubility. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2009;49:1-5.

- ^ https://www.clozapineregistry.com/insert.pdf.ashx

- ^ CLAUDIA WALLIS and JAMES WILLWERTH (July 6, 1992). "Awakenings Schizophrenia a New Drug Brings Patients Back to Life". Time. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ "Clozaril (Clozapine) drug description - FDA approved labeling for prescription drugs and medications at RxList". Rxlist.com. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. "What medications are used to treat schizophrenia?".

- ^ https://www.clozapineregistry.com/Table1.pdf.ashx

- ^ http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/6/43

- ^ http://www.neurology.org/content/41/3/369.short

- ^ MIMS Ireland. April 2007.

- ^ a b Wahlbeck K, Cheine MV, Essali A (2007). Wahlbeck, Kristian (ed.). "Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2). John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: CD000059. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059. ISSN 1464-780X. PMID 10796289.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meltzer HY (1997). "Treatment-resistant schizophrenia--the role of clozapine". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 14 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1185/03007999709113338. PMID 9524789.

- ^ Lee M, Dickson RA, Campbell M, Oliphant J, Gretton H, Dalby JT.. Clozapine and substance abuse in patients with schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43:855–856.

- ^ P03-358 Clozapine may be the answer: a case report of elevated serum creatine kinase in the absence of NMS. A. Mohandas, N. Talwar, A. James Langdon Hospital, Devon Partnership NHS Trust, Dawlish, UK

- ^ https://sites.google.com/site/pharmacologymcqs/clozapine-clozaril.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ http://www.clinicalpharmacology-ip.com/Forms/Monograph/monograph.aspx?cpnum=142&sec=monadve

- ^ [1]

- ^ Baldessarini, Ross J. (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of Psychosis and Mania". In Laurence Brunton, John Lazo, Keith Parker (eds.) (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071422802. OCLC 150149056.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Schwimmer JL, Schaaf JA (1993). "Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States". N Engl J Med. 329 (3): 162–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199307153290303. PMID 8515788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text with registration - ^ Hsyuanyu, Y. and Dunford, H.B. (1999) "Oxidation of Clozapine and Ascorbate by Myeloperoxidase." Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 368(2):412-420 PMID 10441395

- ^ Haas SJ, Hill R, Krum H (2007). "Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a review of 116 cases of suspected myocarditis associated with the use of clozapine in Australia during 1993-2003". Drug Safety. 30 (1): 47–57. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730010-00005. PMID 17194170.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, Harrison-Woolrych M (2008). "Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (5): 759–768. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0509. PMID 18452342.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/409612_2

- ^ rxlist.com / Clozapine side effects

- ^ Ahmed, S.; Chengappa, KN.; Naidu, VR.; Baker, RW.; Parepally, H.; Schooler, NR. (1998). "Clozapine withdrawal-emergent dystonias and dyskinesias: a case series". J Clin Psychiatry. 59 (9): 472–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v59n0906. PMID 9771818.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Szafrański, T.; Gmurkowski, K. (1999). "[Clozapine withdrawal. A review]". Psychiatr Pol. 33 (1): 51–67. PMID 10786215.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA. (1999) Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities. Journal of Clinical Psychology 60 358-63 PMID 10401912

- ^ Nasrallah HA (2008). "Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles". Mol. Psychiatry. 13 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002066. PMID 17848919.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Albaugh VL; Vary TC; Ilkayeva O; Wener BR; Maresca KP; Joyal JL; Breazeale S; Elich TD; Lang CH (2010). "Atypical Antipsychotics Rapidly and Inappropriately Switch Peripheral Fuel Utilization to Lipids, Impairing Metabolic Flexibility in Rodents". Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbq053. PMID 20494946.

- ^ Vaddadi KS, Soosai E, Vaddadi G (2003). "Low blood selenium concentrations in schizophrenic patients on clozapine". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 55 (3): 307–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01773.x. PMC 1884212. PMID 12630982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, Hassan PC (1997). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence". Clin Pharmacokinet. 33 (6): 454–71. doi:10.2165/00003088-199733060-00004. PMID 9435993.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Novartis Pharmaceuticals (April 2006). "Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. p. 36. Retrieved 2007-06-29. [dead link]

- ^ Naheed M, Green B. (2001). "Focus on clozapine". Curr Med Res Opin. 17 (3): 223–9. doi:10.1185/0300799039117069. PMID 11900316.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Rostami-Hodjegan A, Amin AM, Spencer EP, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Flanagan RJ. (2004) "Influence of dose, cigarette smoking, age, sex, and metabolic activity on plasma clozapine concentrations: a predictive model and nomograms to aid clozapine dose adjustment and to assess compliance in individual patients." J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24(1):70-8. PMID 14709950

- ^ Lane HY, Chang YC, Chang WH, Lin SK, Tseng YT, Jann MW. (1999). "Effects of gender and age on plasma levels of clozapine and its metabolites: analyzed by critical statistics". J Clin Psychiatry. 60 (1): 36–40. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0108. PMID 10074876.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Healy 2009,pg 19 Psychiatric drugs explained 5th Ed.Edinburgh : Elsevier Churchill Livingstone

- ^ Novartis Pharmaceuticals. "Clozaril Dosing Guide". Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ^ a b "4.2.1 Antipsychotic drugs". British National Formulary (55 ed.). 2008. p. 195.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Crilly, John (2007). "The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysis". History of Psychiatry. 18 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335. PMID 17580753.

- ^ Healy, David (2004). The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 238–42. ISBN 0-674-01599-1.

- ^ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2005/019758s054ltr.pdf

References

- Benkert, Hippius: Kompendium der Psychiatrischen Pharmakotherapie (German), 4th. ed., Springer Verlag

- B. Bandelow, S. Bleich, and S. Kropp: Handbuch Psychopharmaka (German), 2nd. ed. Hogrefe

- Crilly JF (2007). The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US Market: A review and Analysis. History of Psychiatry, 18(1): 39–60. doi:10.1177/0957154X07070335