Turkey: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("KONDA" from rev 410341819) |

|||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of [[Suleiman the Magnificent]]. The empire was often at odds with the [[Holy Roman Empire]] in its steady advance towards [[Central Europe]] through the Balkans and the southern part of the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]].<ref name="Ottoman_Turkey">{{Cite book|title=History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey|first=Stanford|last=Jay Shaw|coauthors=Kural Shaw, Ezel|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1977|isbn=0-5212-9163-1}}</ref> At sea, the empire contended with the Holy Leagues, composed of [[Habsburg Spain]], the [[Republic of Venice]] and the [[Knights of St. John]], for control of the [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]]. In the [[Indian Ocean]], the Ottoman navy frequently confronted [[Portugal|Portuguese]] fleets in order to defend its traditional monopoly over the maritime trade routes between [[East Asia]] and [[Western Europe]]; these routes faced new competition with the Portuguese discovery of the [[Cape of Good Hope]] in 1488. In addition, the Ottomans were occasionally at war with Persia over territorial disputes or caused by religious differences between 16th and 18th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book|title=A Short History of the Middle East| first=George E. |last=Kirk|publisher=Brill Academic Publishers|year=2008|page=58|isbn=1443725684}}</ref> |

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of [[Suleiman the Magnificent]]. The empire was often at odds with the [[Holy Roman Empire]] in its steady advance towards [[Central Europe]] through the Balkans and the southern part of the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]].<ref name="Ottoman_Turkey">{{Cite book|title=History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey|first=Stanford|last=Jay Shaw|coauthors=Kural Shaw, Ezel|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1977|isbn=0-5212-9163-1}}</ref> At sea, the empire contended with the Holy Leagues, composed of [[Habsburg Spain]], the [[Republic of Venice]] and the [[Knights of St. John]], for control of the [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]]. In the [[Indian Ocean]], the Ottoman navy frequently confronted [[Portugal|Portuguese]] fleets in order to defend its traditional monopoly over the maritime trade routes between [[East Asia]] and [[Western Europe]]; these routes faced new competition with the Portuguese discovery of the [[Cape of Good Hope]] in 1488. In addition, the Ottomans were occasionally at war with Persia over territorial disputes or caused by religious differences between 16th and 18th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book|title=A Short History of the Middle East| first=George E. |last=Kirk|publisher=Brill Academic Publishers|year=2008|page=58|isbn=1443725684}}</ref> |

||

During nearly two [[Decline of the Ottoman Empire|centuries of decline]], the Ottoman Empire gradually shrank in size, military power, and wealth. It entered [[World War I]] on the side of the [[Central Powers]] and was ultimately defeated. During the war, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were deported and exterminated in what many historians call the [[Armenian Genocide]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.umd.umich.edu/dept/armenian/facts/genocide.html|title=FACT SHEET: ARMENIAN GENOCIDE|publisher=[[University of Michigan]]|accessdate=2010-07-15}}</ref><ref>Totten, Samuel, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (eds.) ''Dictionary of Genocide''. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 19. ISBN 0-313-34642-9.</ref> Large scale massacres were also committed against the empire's other [[Christian]] minorities, the [[Ottoman Greeks|Ottoman]] and [[Pontic Greeks]] and [[Assyrians]].<ref>Bloxham. [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TSRkGNoEPFwC&pg=PA150&sig=ACfU3U09_Sjo0a0T4KpiS6QfG-94noUmdg p. 150]</ref><ref name=Levene>Levene (1998)</ref><ref name="Ferguson">Ferguson (2006), p. 180</ref> Following the [[Armistice of Mudros]] on October 30, 1918, the victorious [[Allies of World War I|Allied Powers]] [[partitioning of the Ottoman Empire|partitioned the Ottoman state]] through the 1920 [[Treaty of Sèvres]].<ref name="Ottomans" /> |

During nearly two [[Decline of the Ottoman Empire|centuries of decline]], the Ottoman Empire gradually shrank in size, military power, and wealth. It entered [[World War I]] on the side of the [[Central Powers]] and was ultimately defeated. During the war, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were deported and exterminated in what many historians call the [[Armenian Genocide]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.umd.umich.edu/dept/armenian/facts/genocide.html|title=FACT SHEET: ARMENIAN GENOCIDE|publisher=[[University of Michigan]]|accessdate=2010-07-15}}</ref><ref>Totten, Samuel, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (eds.) ''Dictionary of Genocide''. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 19. ISBN 0-313-34642-9.</ref> The deportation and extermination happened as a result of Armenian revolts and clashes with Turkish civilians, mainly in eastern Turkey. Large scale massacres were also committed against the empire's other [[Christian]] minorities, the [[Ottoman Greeks|Ottoman]] and [[Pontic Greeks]] and [[Assyrians]].<ref>Bloxham. [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TSRkGNoEPFwC&pg=PA150&sig=ACfU3U09_Sjo0a0T4KpiS6QfG-94noUmdg p. 150]</ref><ref name=Levene>Levene (1998)</ref><ref name="Ferguson">Ferguson (2006), p. 180</ref> It is estimated over 500.000 Turks also died during this period, as a result of attrocies commited by Armenian guerrilla bands. In Erivan and other parts of the Caucasus under the control of the Armenian Republic, Turkish villages were destroyed. and the inhabitants were forced to flee or die. Two thirds of the Muslims who had lived in the province of Erivan in 1914 were gone at war's end. A similar fate met Armenians in Turkish Azerbaijan<ref name=Levene>Anatolia 1915:Turks Died, Too, Justin McCarthy, Boston Globe, April 25, 1998</ref> Following the [[Armistice of Mudros]] on October 30, 1918, the victorious [[Allies of World War I|Allied Powers]] [[partitioning of the Ottoman Empire|partitioned the Ottoman state]] through the 1920 [[Treaty of Sèvres]].<ref name="Ottomans" /> |

||

===Republic era=== |

===Republic era=== |

||

Revision as of 09:03, 28 January 2011

Republic of Turkey Türkiye Cumhuriyeti | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: İstiklâl Marşı The Anthem of Independence | |

Location of Turkey | |

| Capital | Ankara |

| Largest city | Istanbul |

| Official languages | Turkish |

| Demonym(s) | Turkish |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

• Founder | Mustafa Kemal Atatürk |

| Abdullah Gül | |

| Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | |

| Mehmet Ali Şahin | |

| Haşim Kılıç | |

| Legislature | Grand National Assembly |

| Succession to the Ottoman Empire | |

| July 24, 1923 | |

• Declaration of Republic | October 29, 1923 |

| Area | |

• Total | 783,562 km2 (302,535 sq mi) (37th) |

• Water (%) | 1.3 |

| Population | |

• 2010 census | 77,804,122 (July 2010 est.) [1] (18th) |

• Density | 92.6/km2 (239.8/sq mi) (108th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $956.576 billion[2] (15) |

• Per capita | $13,392[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $729.051 billion[2] (17) |

• Per capita | $10,206 [2] |

| Gini (2005) | 38 medium |

| HDI (2009) | Error: Invalid HDI value (83rd) |

| Currency | Turkish lira[4] (TRY) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 90 |

| ISO 3166 code | TR |

| Internet TLD | .tr |

Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye), known officially as the Republic of Turkey (), is a Eurasian country that stretches across the Anatolian peninsula in western Asia and Thrace in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe. Turkey is one of the six independent Turkic states. Turkey is bordered by eight countries: Bulgaria to the northwest; Greece to the west; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, Azerbaijan (the exclave of Nakhchivan) and Iran to the east; and Iraq and Syria to the southeast. The Mediterranean Sea and Cyprus are to the south; the Aegean Sea to the west; and the Black Sea is to the north. The Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles (which together form the Turkish Straits) demarcate the boundary between Eastern Thrace and Anatolia; they also separate Europe and Asia.[5] Turkey's location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia makes it a country of significant geostrategic importance.[6][7]

The predominant religion by number of people is Islam--about 97% of the population, the second by number of people is Christianity--0,6%, according to the World Christian Encyclopedia.[8] The country's official language is Turkish, whereas Kurdish and Zazaki languages are spoken by Kurds and Zazas, who comprise 18% of the population. [9] The population of Turkey according to the CIA World Factbook in 2010 is 77.8 million [10]

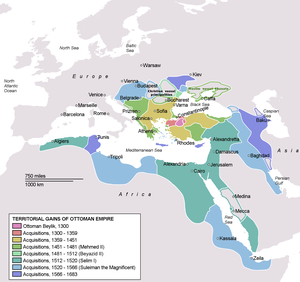

Turks began migrating into the area now called Turkey ("land of the Turks") in the 11th century. The process was greatly accelerated by the Seljuk victory over the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert.[11] Several small beyliks and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm ruled Anatolia until the Mongol Empire's invasion. Starting from the 13th century, the Ottoman beylik united Anatolia and created an empire encompassing much of Southeastern Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. After the Ottoman Empire collapsed following its defeat in World War I, parts of it were occupied by the victorious Allies. A cadre of young military officers, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, organized a successful resistance to the Allies; in 1923, they would establish the modern Republic of Turkey with Atatürk as its first president.

Turkey is a democratic, secular, unitary, constitutional republic, with an ancient cultural heritage. Turkey has become increasingly integrated with the West through membership in organizations such as the Council of Europe, NATO, OECD, OSCE and the G-20 major economies. Turkey began full membership negotiations with the European Union in 2005, having been an associate member of the European Economic Community since 1963 and having reached a customs union agreement in 1995. Turkey has also fostered close cultural, political, economic and industrial relations with the Middle East, the Turkic states of Central Asia and the African countries through membership in organizations such as the Organisation of the Islamic Conference and the Economic Cooperation Organization. Given its strategic location, large as well as powerful economy and army, Turkey is classified as a major regional power.

Etymology

The name of Turkey, Türkiye in the Turkish language, can be divided into two components: the ethnonym Türk and the abstract suffix –iye meaning "owner", "land of" or "related to" (derived from the Arabic suffix –iyya). The first recorded use of the term "Türk" or "Türük" as an autonym is contained in the Orkhon inscriptions of the Göktürks (Celestial Turks) of Central Asia (c. 8th century CE). The English word "Turkey" is derived from the Medieval Latin Turchia (c. 1369). Tu–kin has been attested as early as 177 BCE as a name given by the Chinese to the people living south of the Altay Mountains of Central Asia.

History

Antiquity

The Anatolian peninsula, comprising most of modern Turkey, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited regions in the world. The earliest Neolithic settlements such as Çatalhöyük (Pottery Neolithic), Çayönü (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A to Pottery Neolithic), Nevalı Çori (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B), Hacılar (Pottery Neolithic), Göbekli Tepe (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A) and Mersin are considered to be among the earliest human settlements in the world.[12]

The settlement of Troy started in the Neolithic and continued into the Iron Age. Through recorded history, Anatolians have spoken Indo-European, Semitic and Kartvelian languages, as well as many languages of uncertain affiliation. In fact, given the antiquity of the Indo-European Hittite and Luwian languages, some scholars have proposed Anatolia as the hypothetical center from which the Indo-European languages radiated.[13] The Hattians were an ancient people who inhabited the southeastern part of Anatolia, noted at least as early as ca. 2300. Indo-European Hittites came to Anatolia and gradually absorbed Hattians ca. 2000-1700 BC. The first major empire in the area was founded by the Hittites, from the eighteenth through the 13th century BC. The Assyrians colonized parts of southeastern Turkey as far back as 1950 BC until the year 612 BC, when the Assyrian Empire was conquered by the Chaldean dynasty in Babylon.[14][15] Following the Hittite collapse, the Phrygians, an Indo-European people, achieved ascendancy until their kingdom was destroyed by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BC.[16] The most powerful of Phrygia's successor states were Lydia, Caria and Lycia. The Lydians and Lycians spoke languages that were fundamentally Indo-European, but both languages had acquired non-Indo-European elements prior to the Hittite and Hellenistic periods.

Starting around 1200 BC, the coast of Anatolia was heavily settled by Aeolian and Ionian Greeks. Numerous important cities were founded by these colonists, such as Miletus, Ephesus, Smyrna (modern Izmir), and Byzantium (later Constantinople and Istanbul). The first state established in Anatolia that was called Armenia by neighboring peoples (Hecataeus of Miletus and Behistun Inscription) was the state of the Orontid dynasty. Anatolia was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire during the 6th and 5th centuries BC and later fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BC.[17] Anatolia was subsequently divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms (including Bithynia, Cappadocia, Pergamum, and Pontus), all of which had succumbed to the Roman Republic by the mid-1st century BC.[18] Arsacid Armenia, the first state to accept Christianity as official religion had lands in Anatolia.

In 324, the Roman emperor Constantine I chose Byzantium to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, renaming it New Rome (later Constantinople and Istanbul). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, it became the capital of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire).[19]

Turks and the Ottoman Empire

The House of Seljuk was a branch of the Kınık Oğuz Turks who resided on the periphery of the Muslim world, north of the Caspian and Aral Seas in the Yabghu Khaganate of the Oğuz confederacy [20] in the 10th century. In the 11th century, the Seljuks started migrating from their ancestral homelands towards the eastern regions of Anatolia, which eventually became the new homeland of Oğuz Turkic tribes following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

The victory of the Seljuks gave rise to the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate; which developed as a separate branch of the larger Seljuk Empire that covered parts of Central Asia, Iran, Anatolia and Southwest Asia.[21]

In 1243, the Seljuk armies were defeated by the Mongols, causing the Seljuk empire's power to slowly disintegrate. In its wake, one of the Turkish principalities governed by Osman I would, over the next 200 years, evolve into the Ottoman Empire, expanding throughout Anatolia, the Balkans and the Levant.[22] In 1453, the Ottomans completed their conquest of the Byzantine Empire by capturing its capital, Constantinople.

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. The empire was often at odds with the Holy Roman Empire in its steady advance towards Central Europe through the Balkans and the southern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[7] At sea, the empire contended with the Holy Leagues, composed of Habsburg Spain, the Republic of Venice and the Knights of St. John, for control of the Mediterranean. In the Indian Ocean, the Ottoman navy frequently confronted Portuguese fleets in order to defend its traditional monopoly over the maritime trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe; these routes faced new competition with the Portuguese discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. In addition, the Ottomans were occasionally at war with Persia over territorial disputes or caused by religious differences between 16th and 18th centuries.[23]

During nearly two centuries of decline, the Ottoman Empire gradually shrank in size, military power, and wealth. It entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. During the war, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were deported and exterminated in what many historians call the Armenian Genocide.[24][25] The deportation and extermination happened as a result of Armenian revolts and clashes with Turkish civilians, mainly in eastern Turkey. Large scale massacres were also committed against the empire's other Christian minorities, the Ottoman and Pontic Greeks and Assyrians.[26][27][28] It is estimated over 500.000 Turks also died during this period, as a result of attrocies commited by Armenian guerrilla bands. In Erivan and other parts of the Caucasus under the control of the Armenian Republic, Turkish villages were destroyed. and the inhabitants were forced to flee or die. Two thirds of the Muslims who had lived in the province of Erivan in 1914 were gone at war's end. A similar fate met Armenians in Turkish Azerbaijan[27] Following the Armistice of Mudros on October 30, 1918, the victorious Allied Powers partitioned the Ottoman state through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.[22]

Republic era

The occupation of İstanbul and İzmir by the Allies in the aftermath of World War I prompted the establishment of the Turkish national movement.[7] Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres.[6]

By September 18, 1922, the occupying armies were expelled, and the new Turkish state was established. On November 1, the newly founded parliament formally abolished the Sultanate, thus ending 623 years of Ottoman rule. The Treaty of Lausanne of July 24, 1923, led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the newly formed "Republic of Turkey" as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, and the republic was officially proclaimed on October 29, 1923, in the new capital of Ankara.[7]

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first President of Turkey and subsequently introduced many radical reforms with the aim of founding a new secular republic from the remnants of its Ottoman past.[7] According to the Law on Family Names, the Turkish parliament presented Mustafa Kemal with the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father of the Turks) in 1934.[6]

Turkey remained neutral during most of World War II but entered on the side of the Allies on February 23, 1945, as a ceremonial gesture and in 1945 became a charter member of the United Nations.[29] Difficulties faced by Greece after the war in quelling a communist rebellion, along with demands by the Soviet Union for military bases in the Turkish Straits, prompted the United States to declare the Truman Doctrine in 1947. The doctrine enunciated American intentions to guarantee the security of Turkey and Greece, and resulted in large-scale U.S. military and economic support.[30]

After participating with the United Nations forces in the Korean War, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, becoming a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean. Following a decade of intercommunal violence on the island of Cyprus and the Greek military coup of July 1974, overthrowing President Makarios and installing Nikos Sampson as dictator, Turkey invaded the Republic of Cyprus in 1974.[citation needed] Nine years later the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus which is only recognised by Turkey was established.[31]

The single-party period ended in 1945. It was followed by a tumultuous transition to multiparty democracy over the next few decades, which was interrupted by military coups d'état in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997.[32] In 1984, the PKK began an insurgency against the Turkish government; the conflict, which has claimed over 40,000 lives, continues today.[33] Since the liberalization of the Turkish economy during the 1980s, the country has enjoyed stronger economic growth and greater political stability.[34]

Politics

Turkey is a parliamentary representative democracy. Since its foundation as a republic in 1923, Turkey has developed a strong tradition of secularism.[35] Turkey's constitution governs the legal framework of the country. It sets out the main principles of government and establishes Turkey as a unitary centralized state.

The President of the Republic is the head of state and has a largely ceremonial role. The president is elected for a five-year term by direct elections. Abdullah Gül was elected as president on August 28, 2007, by a popular parliament round of votes, succeeding Ahmet Necdet Sezer.[36]

Executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers which make up the government, while the legislative power is vested in the unicameral parliament, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature, and the Constitutional Court is charged with ruling on the conformity of laws and decrees with the constitution. The Council of State is the tribunal of last resort for administrative cases, and the High Court of Appeals for all others.[37]

The prime minister is elected by the parliament through a vote of confidence in the government and is most often the head of the party having the most seats in parliament. The current prime minister is the former mayor of İstanbul, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose conservative AK party won an absolute majority of parliamentary seats in the 2002 general elections, organized in the aftermath of the economic crisis of 2001, with 34% of the suffrage.[38]

In the 2007 general elections, the AKP received 46.6% of the votes and could defend its majority in parliament.[39] Although the ministers do not have to be members of the parliament, ministers with parliament membership are common in Turkish politics. In 2007, a series of events regarding state secularism and the role of the judiciary in the legislature has occurred. These included the controversial presidential election of Abdullah Gül, who in the past had been involved with Islamist parties;[40] and the government's proposal to lift the headscarf ban in universities, which was annulled by the Constitutional Court, leading to a fine and a near ban of the ruling party.[41]

Universal suffrage for both sexes has been applied throughout Turkey since 1933, and every Turkish citizen who has turned 18 years of age has the right to vote. As of 2004, there were 50 registered political parties in the country.[42] The Constitutional Court can strip the public financing of political parties that it deems anti-secular or separatist, or ban their existence altogether.[43][44]

There are 550 members of parliament who are elected for a four-year term by a party-list proportional representation system from 85 electoral districts which represent the 81 administrative provinces of Turkey (İstanbul is divided into three electoral districts, whereas Ankara and İzmir are divided into two each because of their large populations). To avoid a hung parliament and its excessive political fragmentation, only parties winning at least 10% of the votes cast in a national parliamentary election gain the right to representation in the parliament.[42] Because of this threshold, in the 2007 elections only three parties formally entered the parliament (compared to two in 2002).[45][46]

Human rights in Turkey have been the subject of much controversy and international condemnation. Between 1998 and 2008 the European Court of Human Rights made more than 1,600 judgements against Turkey for human rights violations, particularly the right to life and freedom from torture. Other issues such as Kurdish rights, women's rights and press freedom have also attracted controversy. Turkey's human rights record continues to be a significant obstacle to future membership of the EU.[47] A Class Action has been filed by Tsimpedes Law in Washington DC against Turkey and Northern Cyprus for "the denial of access to and enjoyment of land and property held in the north" of Cyprus. The Class Action lawsuit, originally initiated by Greek Cypriot refugees, from the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, has been joined by Sandra Kocinski, Pat Clarke and Suz Latchford who paid for but have never been given legal title to the Cypriot villas that they purchased.[48]

Foreign relations

Turkey is a founding member of the United Nations (1945), the OECD (1961), the OIC (1969), the OSCE (1973), the ECO (1985), the BSEC (1992) and the G-20 major economies (1999). On October 17, 2008, Turkey was elected as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.[49] Turkey's membership of the council effectively began on January 1, 2009.[49] Turkey had previously been a member of the U.N. Security Council in 1951–1952, 1954–1955 and 1961.[49]

In line with its traditional Western orientation, relations with Europe have always been a central part of Turkish foreign policy. Turkey became a founding member of the Council of Europe in 1949, applied for associate membership of the EEC (predecessor of the European Union) in 1959 and became an associate member in 1963. After decades of political negotiations, Turkey applied for full membership of the EEC in 1987, became an associate member of the Western European Union in 1992, reached a Customs Union agreement with the EU in 1995 and has been in formal accession negotiations with the EU since 2005.[50]

Since 1974 Turkey has not recognized the (essentially Greek Cypriot) Republic of Cyprus as the sole authority on the island, but instead supports the Turkish Cypriot community in the form of the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus which is recognized only by Turkey.[51]

The other defining aspect of Turkey's foreign relations has been its ties with the United States. Based on the common threat posed by the Soviet Union, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, ensuring close bilateral relations with Washington throughout the Cold War. In the post-Cold War environment, Turkey's geostrategic importance shifted towards its proximity to the Middle East, the Caucasus and the Balkans. In return, Turkey has benefited from the United States' political, economic and diplomatic support, including in key issues such as the country's bid to join the European Union.

The independence of the Turkic states of the Soviet Union in 1991, with which Turkey shares a common cultural and linguistic heritage, allowed Turkey to extend its economic and political relations deep into Central Asia,[52] thus enabling the completion of a multi-billion-dollar oil and natural gas pipeline from Baku in Azerbaijan to the port of Ceyhan in Turkey. The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline forms part of Turkey's foreign policy strategy to become an energy conduit to the West. However, Turkey's border with Armenia, a state in the Caucasus, remains closed following its occupation of Azeri territory during the Nagorno-Karabakh War.[53]

Military

The Turkish Armed Forces consists of the Army, the Navy and the Air Force. The Gendarmerie and the Coast Guard operate as parts of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in peacetime, although they are subordinated to the Army and Navy Commands respectively in wartime, during which they have both internal law enforcement and military functions.[54]

The Turkish Armed Forces is the second largest standing armed force in NATO, after the U.S. Armed Forces, with a combined strength of just over a million uniformed personnel serving in its five branches.[55] Turkey is also considered to be the strongest military power of the Middle East region besides Israel. [56][57] [58] [59] [60] Every fit male Turkish citizen otherwise not barred is required to serve in the military for a period ranging from three weeks to fifteen months, dependent on education and job location.[61] Turkey does not recognise conscientious objection and does not offer a civilian alternative to military service.[62]

Turkey is one of five NATO member states which are part of the nuclear sharing policy of the alliance, together with Belgium, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.[63] A total of 90 B61 nuclear bombs are hosted at the Incirlik Air Base, 40 of which are allocated for use by the Turkish Air Force.[64]

In 1998, Turkey announced a program of modernization worth US$160 billion over a twenty year period in various projects including tanks, fighter jets, helicopters, submarines, warships and assault rifles.[65] Turkey is a Level 3 contributor to the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program.[66]

Turkey has maintained forces in international missions under the United Nations and NATO since 1950, including peacekeeping missions in Somalia and former Yugoslavia, and support to coalition forces in the First Gulf War. Turkey maintains 36,000 troops in northern Cyprus; their presence is supported and approved by the de facto local government, but the Republic of Cyprus and the international community regard it as an illegal occupation force, and its presence has also been denounced in several United Nations Security Council resolutions.[67] Turkey has had troops deployed in Afghanistan as part of the U.S. stabilization force and the UN-authorized, NATO-commanded International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) since 2001.[55][68] In 2006, the Turkish parliament deployed a peacekeeping force of Navy patrol vessels and around 700 ground troops as part of an expanded United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in the wake of the Israeli-Lebanon conflict.[69]

The Chief of the General Staff is appointed by the president and is responsible to the prime minister. The Council of Ministers is responsible to parliament for matters of national security and the adequate preparation of the armed forces to defend the country. However, the authority to declare war and to deploy the Turkish Armed Forces to foreign countries or to allow foreign armed forces to be stationed in Turkey rests solely with the parliament.[54] The actual commander of the armed forces is the Chief of the General Staff General Işık Koşaner since August 30, 2010.[70]

Administrative divisions

The capital city of Turkey is Ankara. The territory of Turkey is subdivided into 81 provinces for administrative purposes. The provinces are organized into 7 regions for census purposes; however, they do not represent an administrative structure. Each province is divided into districts, for a total of 923 districts.

Provinces usually bear the same name as their provincial capitals, also called the central district; exceptions to this custom are the provinces of Hatay (capital: Antakya), Kocaeli (capital: İzmit) and Sakarya (capital: Adapazarı). Provinces with the largest populations are Istanbul (13 million), Ankara (5 million), İzmir (4 million), Bursa (3 million) and Adana (2 million).

The biggest city and the pre-Republican capital Istanbul is the financial, economic and cultural heart of the country.[71] An estimated 75.5% of Turkey's population live in urban centers.[72] In all, 19 provinces have populations that exceed 1 million inhabitants, and 20 provinces have populations between 1 million and 500,000 inhabitants. Only two provinces have populations less than 100,000.

Geography

Turkey is a transcontinental[73] Eurasian country. Asian Turkey (made up largely of Anatolia), which includes 97% of the country, is separated from European Turkey by the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles (which together form a water link between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea). European Turkey (eastern Thrace or Rumelia in the Balkan peninsula) comprises 3% of the country.[74]

The territory of Turkey is more than 1,600 kilometres (1,000 mi) long and 800 km (500 mi) wide, with a roughly rectangular shape.[71] It lies between latitudes 35° and 43° N, and longitudes 25° and 45° E. Turkey's area, including lakes, occupies 783,562[75] square kilometres (300,948 sq mi), of which 755,688 square kilometres (291,773 sq mi) are in Southwest Asia and 23,764 square kilometres (9,174 sq mi) in Europe.[71] Turkey is the world's 37th-largest country in terms of area. The country is encircled by seas on three sides: the Aegean Sea to the west, the Black Sea to the north and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. Turkey also contains the Sea of Marmara in the northwest.[76]

The European section of Turkey, Eastern Thrace, forms the borders of Turkey with Greece and Bulgaria. The Asian part of the country, Anatolia, consists of a high central plateau with narrow coastal plains, between the Köroğlu and Pontic mountain ranges to the north and the Taurus Mountains to the south. Eastern Turkey has a more mountainous landscape and is home to the sources of rivers such as the Euphrates, Tigris and Aras, and contains Lake Van and Mount Ararat, Turkey's highest point at 5,165 metres (16,946 ft).[76][77] Lake Tuz, Turkey's third-largest lake, is a macroscopically visible feature in the middle of the country that ironically happens to look like a turkey.

Turkey is divided into seven census regions: Marmara, Aegean, Black Sea, Central Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia and the Mediterranean. The uneven north Anatolian terrain running along the Black Sea resembles a long, narrow belt. This region comprises approximately one-sixth of Turkey's total land area. As a general trend, the inland Anatolian plateau becomes increasingly rugged as it progresses eastward.[76]

Turkey's varied landscapes are the product of complex earth movements that have shaped the region over thousands of years and still manifest themselves in fairly frequent earthquakes and occasional volcanic eruptions. The Bosporus and the Dardanelles owe their existence to the fault lines running through Turkey that led to the creation of the Black Sea. There is an earthquake fault line across the north of the country from west to east, which caused a major earthquake in 1999.[78]

Climate

The coastal areas of Turkey bordering the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea have a temperate Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild to cool, wet winters. The coastal areas of Turkey bordering the Black Sea have a temperate Oceanic climate with warm, wet summers and cool to cold, wet winters. The Turkish Black Sea coast receives the greatest amount of precipitation and is the only region of Turkey that receives high precipitation throughout the year. The eastern part of that coast averages 2,500 millimeters annually which is the highest precipitation in the country.

The coastal areas of Turkey bordering the Sea of Marmara (including Istanbul), which connects the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea, have a transitional climate between a temperate Mediterranean climate and a temperate Oceanic climate with warm to hot, moderately dry summers and cool to cold, wet winters. Snow does occur on the coastal areas of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea almost every winter, but it usually lies no more than a few days. Snow on the other hand is rare in the coastal areas of the Aegean Sea and very rare in the coastal areas of the Mediterranean Sea.

Conditions can be much harsher in the more arid interior. Mountains close to the coast prevent Mediterranean influences from extending inland, giving the central Anatolian plateau of the interior of Turkey a continental climate with sharply contrasting seasons.

Winters on the plateau are especially severe. Temperatures of −30 °C to −40 °C (−22 °F to −40 °F) can occur in eastern Anatolia, and snow may lie on the ground at least 120 days of the year. In the west, winter temperatures average below 1 °C (34 °F). Summers are hot and dry, with temperatures generally above 30 °C (86 °F) in the day. Annual precipitation averages about 400 millimetres (15 in), with actual amounts determined by elevation. The driest regions are the Konya plain and the Malatya plain, where annual rainfall frequently is less than 300 millimetres (12 in). May is generally the wettest month, whereas July and August are the driest.[79]

Economy

Turkey has the world's 15th largest GDP-PPP[80] and 17th largest Nominal GDP.[81] The country is a founding member of the OECD and the G-20 major economies. During the first six decades of the republic, between 1923 and 1983, Turkey has mostly adhered to a quasi-statist approach with strict government planning of the budget and government-imposed limitations over private sector participation, foreign trade, flow of foreign currency, and foreign direct investment. However in 1983 Prime Minister Turgut Özal initiated a series of reforms designed to shift the economy from a statist, insulated system to a more private-sector, market-based model.[34]

The reforms spurred rapid growth, but this growth was punctuated by sharp recessions and financial crises in 1994, 1999 (following the earthquake of that year),[82] and 2001,[83] resulting in an average of 4% GDP growth per annum between 1981 and 2003.[84] Lack of additional fiscal reforms, combined with large and growing public sector deficits and widespread corruption, resulted in high inflation, a weak banking sector and increased macroeconomic volatility.[85]

Since the economic crisis of 2001 and the reforms initiated by the finance minister of the time, Kemal Derviş, inflation has fallen to single-digit numbers, investor confidence and foreign investment have soared, and unemployment has fallen. The IMF forecasts a 6% inflation rate for Turkey in 2008.[86] Turkey has gradually opened up its markets through economic reforms by reducing government controls on foreign trade and investment and the privatisation of publicly owned industries, and the liberalisation of many sectors to private and foreign participation has continued amid political debate.[87] The public debt to GDP ratio, while well below its levels during the recession of 2001, reached 46% in 2010 Q3.

The GDP growth rate from 2002 to 2007 averaged 7.4%,[88] which made Turkey one of the fastest growing economies in the world during that period. However, GDP growth slowed down to 4.5% in 2008,[89] and in early 2009 the Turkish economy was affected by the global financial crisis, with the IMF forecasting an overall recession of 5.1% for the year, compared to the Turkish government estimate of 3.6%.[90]

Turkey's economy is becoming more dependent on industry in major cities, mostly concentrated in the western provinces of the country, and less on agriculture, however traditional agriculture is still a major pillar of the Turkish economy. In 2007, the agricultural sector accounted for 9% of GDP, while the industrial sector accounted for 31% and the services sector accounted for 59%.[89] However, agriculture still accounted for 27% of employment.[91]

According to Eurostat data, Turkish PPS GDP per capita stood at 45 per cent of the EU average in 2008.[92]

The tourism sector has experienced rapid growth in the last twenty years, and constitutes an important part of the economy. In 2008 there were 31 million visitors to the country, who contributed $22 billion to Turkey's revenues.[93]

Other key sectors of the Turkish economy are banking, construction, home appliances, electronics, textiles, oil refining, petrochemical products, food, mining, iron and steel, machine industry and automotive. Turkey has a large and growing automotive industry, which produced 1,147,110 motor vehicles in 2008, ranking as the 6th largest producer in Europe (behind the United Kingdom and above Italy) and the 15th largest producer in the world.[94][95] Turkey is also one of the leading shipbuilding nations; in 2007 the country ranked 4th in the world (behind China, South Korea and Japan) in terms of the number of ordered ships, and also 4th in the world (behind Italy, USA and Canada) in terms of the number of ordered mega yachts.[96]

In the early years of this century the chronically high inflation was brought under control and this led to the launch of a new currency, the Turkish new lira, on January 1, 2005, to cement the acquisition of the economic reforms and erase the vestiges of an unstable economy.[97] On January 1, 2009, the New Turkish Lira was renamed once again as the Turkish Lira, with the introduction of new banknotes and coins. As a result of continuing economic reforms, inflation dropped to 8.2% in 2005, and the unemployment rate to 10.3%.[98] In 2004, it was estimated that 46% of total disposable income was received by the top of 20% income earners, while the lowest 20% received 6%.[99]

Turkey has taken advantage of a customs union with the European Union, signed in 1995, to increase its industrial production destined for exports, while at the same time benefiting from EU-origin foreign investment into the country. Turkey now has also opportunity of a really decent free trade agreement with the European Union (EU) - without full membership - that allows it to manufacture for tarif-free sale throughout the EU market.[100][101] By 2007 exports had reached $115 billion[89] (main export partners: Germany 11%, UK 8%, Italy 7%, France 6%, Spain 4%, USA 4%; total EU exports 57%.) However larger imports, which amounted to $162 billion in 2007,[89] threatened the balance of trade (main import partners: Russia 14%, Germany 10%, China 8%, Italy 6%, USA 5%, France 5%, Iran 4%, UK 3%; total EU imports 40%; total Asia imports 27%).[102][103] Turkey's exports amounted to $142 billion in 2008, while imports amounted to $205 billion.[89]

After years of low levels of foreign direct investment (FDI), Turkey succeeded in attracting $22 billion in FDI in 2007 and is expected to attract a higher figure in following years.[104] A series of large privatizations, the stability fostered by the start of Turkey's EU accession negotiations, strong and stable growth, and structural changes in the banking, retail, and telecommunications sectors have all contributed to a rise in foreign investment.[87]

Demographics

More than 77 million people live in Turkey, three quarters of them in towns and cities, and the population is increasing by 1.5% each year (according to the 2009 census). In 1927 when the first census was taken in Turkey, the population was 13.6 million.[106] It has an average population density of 92 people per km². People within the 15–64 age group constitute 67% of the total population, the 0–14 age group is 26% of the population, and people 65 years old and above make up 7%.[107]

Regions of Turkey with the largest populations are İstanbul (+12 million), Ankara (+4.4 million), İzmir (+3.7 million), Bursa (+2.4 million), Adana (+2.0 million) and Konya (+1.9 million).[108] An estimated 70.5% of the population live in urban centers.[109] In all, 18 provinces have populations that exceed 1 million inhabitants, and 21 provinces have populations between 1 million and 500,000 inhabitants. Only two provinces have populations less than 100,000.

Life expectancy stands at 71.1 years for men and 75.3 years for women, with an overall average of 73.2 years for the populace as a whole.[110] Education is compulsory and free from ages 6 to 15. The literacy rate is 96% for men and 80.4% for women, with an overall average of 88.1%.[111] The low figures for women are mainly due to the traditional customs of the Arabs and Kurds who live in the southeastern provinces of the country.[112]

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as "anyone who is bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship"; therefore, the legal use of the term "Turkish" as a citizen of Turkey is different from the ethnic definition. However, the majority of the Turkish population are of Turkish ethnicity.

The Kurds, a distinct ethnic group concentrated mainly in the southeastern provinces of the country, are the largest non-Turkic ethnicity, estimated at about 18% of the population according to the CIA.[113] Minorities other than the three officially recognized ones do not have any special group privileges, while the term "minority" itself remains a sensitive issue in Turkey. Reliable data on the ethnic mix of the population is not available, because Turkish census figures do not include statistics on ethnicity.[114]

Other major ethnic groups (large portions of whom have been extensively Turkicized since the Seljuk and Ottoman periods) include the Abkhazians, Adjarians, Albanians, Arabs, Assyrians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Hamshenis, Laz, Pomaks (Bulgarians), Roma, Zazas and the three officially recognized minorities (per the Treaty of Lausanne), i.e. the Armenians, Greeks and Jews. Signed on January 30, 1923, a bilateral accord of population exchange between Greece and Turkey took effect in the 1920s, with close to 1.5 million Greeks moving from Turkey and some 500,000 Turks coming from Greece.[115]

Minorities of West European origin include the Levantines (or Levanter, mostly of French, Genoese and Venetian descent) who have been present in the country (particularly in Istanbul[116] and İzmir[117]) since the medieval period.

Language

Turkish is the sole official language throughout Turkey. Reliable figures for the linguistic breakdown of the populace are not available for reasons similar to those cited above.[114] According to CIA the Turkish language is spoen by 70-75% and Kurdish language by 18%.[118] The public broadcaster TRT broadcasts programmes in the local languages and dialects of Arabic, Bosnian, Circassian and Kurdish a few hours a week.[119] A completely Kurdish-language public television channel, TRT 6, was opened in early 2009.[120]

Religion

Turkey is a secular state with no official state religion; the Turkish Constitution provides for freedom of religion and conscience.[121][122] Islam is the dominant religion of Turkey by number of people with about 97% Muslims,[8] with no religious Muslims the number is over 99%.[123][124][125] Research firms suggest the actual Muslim figure is around 98%,[126] or 97%.[127] There are about 400,000 people, that follow Christianity,[8] mostly Armenian Apostolic, Assyrian Church of the East and Greek Orthodox, there are also group of Jews, mainly Sephardi (26,000 people).[128]

Though there are no exact figures on religious sects, according to a 2006 survey, 82% were identified as Sunni Hanafi, 9.1% Sunni Shafi'i, and 5.7% were Alevi.[129] Though academics suggest the Alevi population may be from 15 to 20 million.[130][131] Alevi community is sometimes classified within Twelver Shi'a Islam.[132] According to Aksiyon magazine, the number of Shiite Twelvers (excluding Alevis) is 3 million (4.2%), and they live in Istanbul, Iğdır, Kars, Ankara, İzmir, Manisa, Çorum, Muğla, Ağrı and Aydın.[133] There are also some Sufi practitioners.[134] The highest Islamic religious authority is the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Turkish: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı), it interprets the Hanafi school of law, and is responsible for regulating the operation of the country's 80,000 registered mosques and employing local and provincial imams.[135] The role of religion has been controversial debate over the years since the formation of Islamist parties.[136] Turkey was founded upon a strict secular constitution which forbids the influence of any religion, including Islam. There are sensitive issues, such as the fact that the wearing of the Hijab is banned in universities and public or government buildings as some view it as a symbol of Islam - though there have been efforts to lift the ban.[137][138][139][140] The vast majority of the present-day Turkish people are Muslim and the most popular sect is the Hanafite school of Sunni Islam, which was officially espoused by the Ottoman Empire; according to the KONDA Research and Consultancy survey carried out throughout Turkey on 2007[141]:

- 40.8% defined themselves as "a religious person who strives to fulfill religious obligations" (Religious)

- 42.3 % defined themselves as "“a believer who does not fulfill religious obligations" (Not religious).

- 4.0% defined themselves as "a fully devout person fulfilling all religious obligations" (Fully devout).

- 10.3% defined themselves as "someone who does not believe in religious obligations" (Non-believer).

- 4.09%' defined themselves as "someone with no religious conviction" (Atheist).

The Orthodox Church has been headquartered in Istanbul since the 4th century AD.

The Bahá'í Faith in Turkey has roots in Bahá'u'lláh's, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, being exiled to Constantinople, current-day Istanbul, by the Ottoman authorities. Bahá'ís cannot register with the government officially[142] but there are probably 10[143] to 20[144] thousand Bahá'ís, and around a hundred Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assemblies in Turkey.[145]

Culture

Turkey has a very diverse culture that is a blend of various elements of the Oğuz Turkic, Anatolian, Ottoman (which was itself a continuation of both Greco-Roman and Islamic cultures) and Western culture and traditions, which started with the Westernization of the Ottoman Empire and still continues today. This mix originally began as a result of the encounter of Turks and their culture with those of the peoples who were in their path during their migration from Central Asia to the West.[146][147]

As Turkey successfully transformed from the religion-based former Ottoman Empire into a modern nation-state with a very strong separation of state and religion, an increase in the modes of artistic expression followed. During the first years of the republic, the government invested a large amount of resources into fine arts; such as museums, theatres, opera houses and architecture. Diverse historical factors play important roles in defining the modern Turkish identity. Turkish culture is a product of efforts to be a "modern" Western state, while maintaining traditional religious and historical values.[146]

Turkish music and literature form great examples of such a mix of cultural influences, which were a result of the interaction between the Ottoman Empire and the Islamic world along with Europe, thus contributing to a blend of Turkic, Islamic and European traditions in modern-day Turkish music and literary arts.[148] Turkish literature was heavily influenced by Persian and Arabic literature during most of the Ottoman era, though towards the end of the Ottoman Empire, particularly after the Tanzimat period, the effect of both Turkish folk and European literary traditions became increasingly felt. The mix of cultural influences is dramatized, for example, in the form of the "new symbols [of] the clash and interlacing of cultures" enacted in the works of Orhan Pamuk, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature.[149] According to Konda public opinion researchers, 70% of Turkish citizens never read books.[150]

Architectural elements found in Turkey are also testaments to the unique mix of traditions that have influenced the region over the centuries. In addition to the traditional Byzantine elements present in numerous parts of Turkey, many artifacts of the later Ottoman architecture, with its exquisite blend of local and Islamic traditions, are to be found throughout the country, as well as in many former territories of the Ottoman Empire. Mimar Sinan is widely regarded as the greatest architect of the classical period in Ottoman architecture. Since the 18th century, Turkish architecture has been increasingly influenced by Western styles, and this can be particularly seen in Istanbul where buildings like Dolmabahçe and Çırağan Palaces are juxtaposed next to numerous modern skyscrapers, all of them representing different traditions.[151]

Sports

The most popular sport in Turkey is football.[152] Turkey's top teams include Galatasaray, Fenerbahçe and Beşiktaş. In 2000, Galatasaray cemented its role as a major European club by winning the UEFA Cup and UEFA Super Cup. Two years later the Turkish national team finished third in the 2002 World Cup Finals in Japan and South Korea, while in 2008 the national team reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Euro 2008 competition. The Atatürk Olympic Stadium in Istanbul hosted the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final, while the Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium in Istanbul hosted the 2009 UEFA Cup Final.

Other mainstream sports such as basketball and volleyball are also popular. Turkey hosted the finals of EuroBasket 2001 and the finals of the 2010 FIBA World Championship, winning second place on both occasions; while Efes Pilsen S.K. won the Korac Cup in 1996, finished second in the Saporta Cup of 1993, and made it to the Final Four of Euroleague and Suproleague in 2000 and 2001.[153] Turkish basketball players such as Mehmet Okur and Hidayet Türkoğlu have also been successful in the NBA. Women's volleyball teams, namely Eczacıbaşı, Vakıfbank Güneş Sigorta and Fenerbahçe Acıbadem, have won numerous European championship titles and medals.

The traditional Turkish national sport has been yağlı güreş (oiled wrestling) since Ottoman times.[154] Edirne has hosted the annual Kırkpınar oiled wrestling tournament since 1361.[155] International wrestling styles governed by FILA such as Freestyle wrestling and Greco-Roman wrestling are also popular, with many European, World and Olympic championship titles won by Turkish wrestlers both individually and as a national team.[156]

Weightlifting has been a successful Turkish sport. Turkish weightlifters, both male and female, have broken numerous world records and won several European,[157] World and Olympic[158] championship titles. Naim Süleymanoğlu and Halil Mutlu have achieved legendary status as one of the few weightlifters to have won three gold medals in three Olympics.

Motorsport is another popular sport. Rally of Turkey was included to the FIA World Rally Championship calendar in 2003,[159] and the Turkish Grand Prix was included to the Formula One racing calendar in 2005.[160] Other important annual motorsports events which are held at the Istanbul Park racing circuit include the MotoGP Grand Prix of Turkey, the FIA World Touring Car Championship, the GP2 Series and the Le Mans Series. From time to time Istanbul and Antalya also host the Turkish leg of the F1 Powerboat Racing championship; while the Turkish leg of the Red Bull Air Race World Series, an air racing competition, takes place above the Golden Horn in Istanbul. Surfing, snowboarding, skateboarding, paragliding and other extreme sports are becoming more popular every year.

See also

Notes

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2010". IMF. 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2010-12-28. Cite error: The named reference "imf2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ The Turkish lira (Türk Lirası, TL) replaced the Turkish new lira on January 1, 2009.

- ^ National Geographic Atlas of the World (7th ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic. 1999. ISBN 0-7922-7528-4. "Europe" (pp. 68–69); "Asia" (pp. 90–91): "A commonly accepted division between Asia and Europe ... is formed by the Ural Mountains, Ural River, Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and the Black Sea with its outlets, the Bosporus and Dardanelles."

- ^ a b c Mango, Andrew (2000). Ataturk. Overlook. ISBN 1-5856-7011-1.

- ^ a b c d e Shaw, Stanford Jay (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey; Vol.1, Empire of the Gazis. the rise and decline of the Ottoman Empire, 1280-1808. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5212-9163-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Ottoman_Turkey" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c [1]

- ^ CIA World Factbook gives 18% Kurds

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html

- ^ http://countrystudies.us/turkey/5.htm

- ^ Thissen, Laurens (2001-11-23). "Time trajectories for the Neolithic of Central Anatolia" (PDF). CANeW – Central Anatolian Neolithic e-Workshop. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Balter, Michael (2004-02-27). "Search for the Indo-Europeans: Were Kurgan horsemen or Anatolian farmers responsible for creating and spreading the world's most far-flung language family?". Science. 303 (5662): 1323. doi:10.1126/science.303.5662.1323. PMID 14988549.

- ^ "Ziyaret Tepe - Turkey Archaeological Dig Site". .uakron.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "Assyrian Identity In Ancient Times And Today'" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2000). "Anatolia and the Caucasus, 2000–1000 B.C. in Timeline of Art History.". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hooker, Richard (1999-06-06). "Ancient Greece: The Persian Wars". Washington State University, WA, United States. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2000). "Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C. – 1 A.D. in Timeline of Art History.". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Daniel C. Waugh (2004). "Constantinople/Istanbul". University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ Wink, Andre (1990). Al Hind: The Making of the Indo Islamic World, Vol. 1, Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09249-8.

- ^ Mango, Cyril (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-1981-4098-3.

- ^ a b Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. Morrow. ISBN 0-6880-3093-9.

- ^ Kirk, George E. (2008). A Short History of the Middle East. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 58. ISBN 1443725684.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: ARMENIAN GENOCIDE". University of Michigan. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ^ Totten, Samuel, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (eds.) Dictionary of Genocide. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 19. ISBN 0-313-34642-9.

- ^ Bloxham. p. 150

- ^ a b Levene (1998) Cite error: The named reference "Levene" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ferguson (2006), p. 180

- ^ "Growth in United Nations membership (1945–2005)". United Nations. 2006-07-03. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ^ Huston, James A. (1988). Outposts and Allies: U.S. Army Logistics in the Cold War, 1945–1953. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 0-9416-6484-8.

- ^ "Timeline: Cyprus". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2006-12-25.

- ^ Hale, William Mathew (1994). Turkish Politics and the Military. Routledge, UK. ISBN 0-4150-2455-2.

- ^ "Turkey's PKK peace plan delayed". BBC. 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ a b Nas, Tevfik F. (1992). Economics and Politics of Turkish Liberalization. Lehigh University Press. ISBN 0-9342-2319-X.

- ^ Çarkoğlu, Ali (2004). Religion and Politics in Turkey. Routledge, UK. ISBN 0-4153-4831-5.

- ^ "Turks elect ex-Islamist president". BBC. 2007-11-02. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Turkish Directorate General of Press and Information (2001-10-17). "Turkish Constitution". Turkish Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "Turkey's old guard routed in elections". BBC. 2002-11-04. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Turkey re-elects governing party". BBC. 2007-07-22. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ Turks elect ex-Islamist president BBC. (2007-08-28). Retrieved on 2009-09-22.

- ^ Court annuls Turkish scarf reform BBC. (2007-06-05). Retrieved on 2009-09-22.

- ^ a b Turkish Directorate General of Press and Information (2004-08-24). "Political Structure of Turkey". Turkish Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Euro court backs Turkey Islamist ban". BBC. 2001-07-31. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "Turkey's Kurd party ban criticised". BBC. 2003-03-14. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Hardy, Roger (2002-11-04). "Turkey leaps into the unknown". BBC. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (2007-11-02). "Turkey awaits AKP's next step". BBC. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ "Human rights in Turkey: still a long way to go to meet accession criteria", European Parliament Human Rights committee, October 26, 2010.

- ^ Buyers of property in the north join US lawsuit, 17 January 2010, NorthCyprusDaily.com

- ^ a b c "Hürriyet: Türkiye'nin üyeliği kabul edildi (2008-10-17)". Hurarsiv.hurriyet.com.tr. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Chronology of Turkey-EU relations". Turkish Secretariat of European Union Affairs. Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ^ Mardell, Mark (2006-12-11). "Turkey's EU membership bid stalls". BBC. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ^ Bal, Idris (2004). Turkish Foreign Policy In Post Cold War Era. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-5811-2423-6.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State: Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Armenia: Respect for Human Rights. Section 1, a". State.gov. 2007-03-06. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ a b Turkish General Staff (2006). "Turkish Armed Forces Defense Organization". Turkish Armed Forces. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^ a b Economist Intelligence Unit:Turkey, p.23 (2005)

- ^ Stratfor: "Turkey and Russia on the Rise", by Reva Bhalla, Lauren Goodrich and Peter Zeihan. March 17, 2009.

- ^ "The Geopolitics of Turkey". Stratfor. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ http://www.europesworld.org/NewEnglish/Home_old/Article/tabid/191/ArticleType/ArticleView/ArticleID/21291/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- ^ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_7057/is_2_9/ai_n28498823/pg_7/

- ^ http://heptagonpost.com/www.heptagonpost.com/dessi/can_turkey_be_a_source_of_stability_in_the_middle_east

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Directorate for Movements of Persons, Migration and Consular Affairs – Asylum and Migration Division (2001). "Turkey/Military service" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-22. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[dead link] - ^ "EBCO - European Bureau for Conscientious Objection". Ebco-beoc.eu. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "Der Spiegel: ''Foreign Minister Wants US Nukes out of Germany'' (2009-04-10)". Spiegel.de. 2009-03-30. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen. "NRDC: U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe" (PDF). Natural Resources Defense Council, 2005. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Economist Intelligence Unit:Turkey, p.22 (2005)

- ^ US Department of Defense (2002-07-11). "DoD, Turkey sign Joint Strike Fighter Agreement". US Department of Defense. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ O.P. Richmond. Mediating in Cyprus: the Cypriot communities and the United Nations. Psychology Press, 1998. p. 260 [2]

- ^ Turkish General Staff (2006). "Brief History of ISAF". Turkish Armed Forces. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ "Turkish troops arrive in Lebanon". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-10-20. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ "General Işık Koşaner". NATO. 2008-09-02. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ a b c US Library of Congress. "Geography of Turkey". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2010). "2009 Census, population living in cities". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ Sabancı University (2005). "Geography of Turkey". Sabancı University. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ "Turkey". Turkish Odyssey. 2000-02-02. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "UN Demographic Yearbook, accessed April 16, 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ a b c Turkish Ministry of Tourism (2005). "Geography of Turkey". Turkish Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ NASA – Earth Observatory (2001). "Mount Ararat (Ağrı Dağı), Turkey". NASA. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ "Brief Seismic History of Turkey". University of South California, Department of Civil Engineering. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ Turkish State Meteorological Service (2006). "Climate of Turkey". Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ The World Bank: World Economic Indicators Database. GDP (PPP) 2008. Data for the year 2008. Last revised on July 1, 2009.

- ^ The World Bank: World Economic Indicators Database. GDP (Nominal) 2008. Data for the year 2008. Last revised on July 1, 2009.

- ^ "Turkish quake hits shaky economy". British Broadcasting Corporation. 1999-08-17. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ "'Worst over' for Turkey". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2002-02-04. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ World Bank (2005). "Turkey Labor Market Study" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform – Turkey: crucial support for economic recovery : 2002. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2002. ISBN 92-64-19808-3.

- ^ IMF: World Economic Outlook Database, April 2008. Inflation, end of period consumer prices. Data for 2006, 2007 and 2008.

- ^ a b Jorn Madslien (2006-11-02). "Robust economy raises Turkey's hopes". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ Dilenschneider Group and Pangaeia Group, "Turkey 360: Did You Know", Foreign Affairs, January/February 2008

- ^ a b c d e "Turkey". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2009-05-15.[dead link]

- ^ ""Turkey's fragile economy" (2009-07-16)". The Economist. 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Turkey - Agriculture and Enlargement" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "GDP per capita in PPS" (PDF). Eurostat. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ "Tourism Statistics in 2008". TURKSTAT. 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ "Türkiye otomotiv sektöründe büyüyor". Ulaşım Online. 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ "2008 PRODUCTION STATISTICS". OICA. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Catania Investments: Turkish Shipbuilding Industry

- ^ "Turkey knocks six zeros off lira". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2004-12-31. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ World Bank (2005). "Data and Statistics for Turkey". World Bank. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2006-02-27). "The result of Income Distribution". Turkish Statistical Institute. Archived from the original on 2006-10-14. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ http://www.europeanbusiness.gr/page.asp?pid=829

- ^ Bartolomiej Kaminski (2006-05-01). "Turkey's evolving trade integration into Pan-European markets" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gümrükler Genel Müdürlüğü. "2006–2007 Seçilmiş Ülkeler İstatistikleri". Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "Turkey puts 2008 export target at 125 bln dollars". Xinhua. 2008-01-02. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ "Yabancı sermayede rekor". Hürriyet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ [3]

- ^ "Turkey". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2010). "2009 Census, population statistics in 2009". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2008). "2007 Census, population by provinces". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2008). "2007 Census,population living in cities". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2004-10-18). "Population and Development Indicators – Population and Demography". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (2004-10-18). "Population and Development Indicators – Population and Education". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ Jonny Dymond (2004-10-18). "Turkish girls in literacy battle". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ CIA World Factbook

- ^ a b Extra, Guus (2001). The other languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-8535-9509-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Diaspora Welcomes the Pope. Spiegel Online. November 28, 2006.

- ^ "NTV-MSNBC: "Giovanni Scognamillo ile sinema üzerine"". Arsiv.ntvmsnbc.com. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Sabah daily newspaper: "Onlar İzmirli Hristiyan Türkler"". Arsiv.sabah.com.tr. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ a b [4]

- ^ Turkish Directorate General of Press and Information (2003). "Historical background of radio and television broadcasting in Turkey". Turkish Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 2006-08-30. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ Nasuhi Güngör (2009). "Kurdish TRT". Zaman. Retrieved 2009-02-25. [dead link]

- ^ Prof. Dr. Axel Tschentscher, LL.M. "ICL – International Constitutional Law – Turkey Constitution". Servat.unibe.ch. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Turkey: Islam and Laicism Between the Interests of State, Politics, and Society" (PDF). Peace Research Institute Frankfurt. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ From the introduction of Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East edited by her, B. Kellner-Heinkele, & A. Otter-Beaujean. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

- ^ "Turkey". World Factbook. CIA. 2010.

- ^ "TURKEY" (PDF). Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Mapping the Global Muslim Population Pew Forum. October 2009. Retrieved on 2010-09-13.

- ^ "KONDA Research and Consultancy – Religion, Secularism and the veil in daily life" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "An Overview of the History of the Jews in Turkey" (PDF). American Sephardi Federation. 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Social Structure Survey 2006 KONDA. p.28. Retrieved on 2010-09-16.

- ^ Turkey - International Religious Freedom Report 2007 U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2010-09-16.

- ^ Asia Times Feb 18, 2010. Retrieved on 2010-09-16

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)[dead link] - ^ "Caferi İmamlar" (in Turkish). Aksiyon.com.tr. 2004-10-11. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "''Sufism''". All about Turkey. 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Bureau of Democracy, Human rights and Labor – International Religious Freedom Report 2007– Turkey". State.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Civil society, religion, and the nation: modernization in intercultural context : Russia, Japan, Turkey Gerrit Steunebrink, Evert van der Zweerde. pp.175-184.

- ^ "Headscarf row in Turkey parliament". BBC News. 1999-05-03. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Turkey eases ban on headscarves". BBC News. 2008-02-09. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Turkish leaders face court case". BBC News. 2008-03-31. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ "Turkey headscarf ruling attacked". BBC News. 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2010-11-01. and "Turkish PM attacks proposed ban". BBC News. 2008-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ KONDA Research and Consultancy (2007-09-08). "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in daily life" (PDF). Milliyet.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2008 - Turkey". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "For the first time, Turkish Baha'i appointed as dean". The Muslim Network for Baha’i Rights. 2008-12-13. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ^ "Turkey /Religions & Peoples". LookLex Encyclopedia. LookLex Ltd. 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ^ Walbridge, John (March, 2002). "Chapter Four - The Baha'i Faith in Turkey". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 06 (01).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Kaya, İbrahim (2003). Social Theory and Later Modernities: The Turkish Experience. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-8532-3898-7.

- ^ Royal Academy of Arts (2005). "Turks – A Journey of a Thousand Years: 600–1600". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ Cinuçen Tanrıkorur. "The Ottoman music". www.turkmusikisi.com. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ "Pamuk wins Nobel Literature prize". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ Azeri-Press Agency (APA) (23 Feb 2009). "70 percent of Turkish citizens never read book". Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Goodwin, Godfrey (2003). A History of Ottoman Architecture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-5002-7429-0.

- ^ Burak Sansal (2006). "Sports in Turkey". allaboutturkey.com. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ Historic achievements of the Efes Pilsen Basketball Team[dead link]

- ^ Burak Sansal (2006). "Oiled Wrestling". allaboutturkey.com. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ "Kırkpınar Oiled Wrestling Tournament: History". Kirkpinar.com. 2007-04-21. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Christiane Gegner. "FILA Wrestling Database". Iat.uni-leipzig.de. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- ^ Turkish Weightlifting Federation: List of European (Avrupa) records by male and female weightlifters[dead link]

- ^ Turkish Weightlifting Federation: List of World (Dünya) and Olympic (Olimpiyat) records by male and female weightlifters

- ^ WRC Rally of Turkey: Brief event history[dead link]

- ^ "BBC Sport: Formula 1 circuit guide: Istanbul, Turkey". BBC News. 2006-02-22. Retrieved 2010-11-01.

References

|

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html

|

Further reading

- Mango, Andrew (2004). The Turks Today. Overlook. ISBN 1585676152.

- Bozarslan, Hamit 'Turkey: Postcolonial discourse in a non-colonised state', in Prem Poddar et al. , Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures—Continental Europe and its Colonies, Edinburgh University Press, 2008

- Pope, Hugh (2004). Turkey Unveiled. Overlook. ISBN 1585675814.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Revolinski, Kevin (2006). The Yogurt Man Cometh: Tales of an American Teacher in Turkey. Citlembik. ISBN 9944424013.

- Roxburgh, David J. (ed.) (2005). Turks: A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600–1600. Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 1-903973-56-2.

- Turkey: A Country Study (1996). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0864-6.

- M. Nicolas J. Firzli, ed. (2010). “Turkey, Asia and the Iranian Nuclear Crisis” (PDF). Commentary. Vol. 5. Vienna, Austria: Vienna Review. pp. 1–4.

External links

- Official website

- "Turkey". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Turkey at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of Turkey

Wikimedia Atlas of Turkey- Template:Wikitravel

- Saglik & Tatil truzim Türkiyede

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Turkey

- Aegean Sea

- Bicontinental countries

- Black Sea countries

- Countries of the Mediterranean Sea

- Developing 8 Countries member states

- Eastern Europe

- Eurasia

- European countries

- G20 nations

- Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- Modern Turkic states

- Near Eastern countries

- Republics

- Southwest Asian countries

- States and territories established in 1923

- Western Asia