LSD: Difference between revisions

Tags: nowiki added Visual edit |

|||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

=== Alteration of gene expression === |

=== Alteration of gene expression === |

||

Chronic administration of LSD alters [[gene expression]] profiles in the [[medial prefrontal cortex]]. Evidence form studies in rodents demonstrates that chronic LSD affects the expression of [[DRD2]], [[GABRB1]], [[NR2A]], [[Krox20]], [[ATP5D]], [[NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone), alpha 1|NDUFA1]], [[Neuropeptide Y|NPY]], and [[BDNF]], among others. Many processes identified as altered by chronic LSD are also implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.<ref>Martin DA (2014): Neuropharmacology. Epub. PMID 24704148</ref> |

Chronic administration of LSD alters [[gene expression]] profiles in the [[medial prefrontal cortex]]. Evidence form studies in rodents demonstrates that chronic LSD affects the expression of [[DRD2]], [[GABRB1]], [[NR2A]], [[Krox20]], [[ATP5D]], [[NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone), alpha 1|NDUFA1]], [[Neuropeptide Y|NPY]], and [[BDNF]], among others.<sup style="white-space:nowrap;" class="noprint Inline-Template Template-Fact">[<i>[[Wikipedia:Citation needed|<span class="" title="This claim needs references to reliable sources.<nowiki/> (September 2014)">citation needed</span>]]</i>]</sup> Many processes identified as altered by chronic LSD are also implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.<ref>Martin DA (2014): Neuropharmacology. Epub. PMID 24704148</ref> |

||

=== Treatment of intoxication === |

=== Treatment of intoxication === |

||

Revision as of 15:54, 27 January 2015

This article needs attention from an expert in Pharmacology. The specific problem is: Poorly-sourced content in Adverse drug interactions (has been removed). (June 2014) |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | LSD, LSD-25, lysergide, D-lysergic acid diethyl amide, N,N- diethyl- D- lysergamide |

| Addiction liability | None[1] |

| Routes of administration | Oral, sublingual, Intravenous, Ocular, Intramuscular |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3–5 hours[2][3] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.031 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H25N3O |

| Molar mass | 323.43 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 80 to 85 °C (176 to 185 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

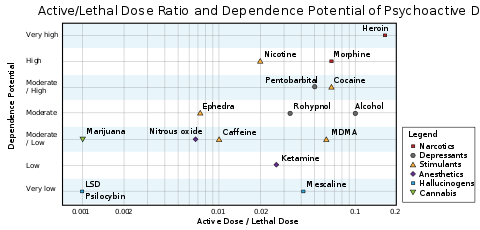

Lysergic acid diethylamide (/daɪ eθəl eɪmaɪd/), abbreviated LSD or LSD-25, also known as lysergide (INN) and colloquially as acid, is a psychedelic drug of the ergoline family, well known for its psychological effects, which can include altered thinking processes, closed- and open-eye visuals, synesthesia, an altered sense of time and spiritual experiences, as well as for its key role in 1960s counterculture. It is used mainly as an entheogen, recreational drug, and as an agent in psychedelic therapy. LSD is non-addictive, is not known to cause brain damage, and has extremely low toxicity relative to dose.[4] However, acute adverse psychiatric reactions such as anxiety, paranoia, and delusions are possible.[5]

LSD was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938 from ergotamine, a chemical derived by Arthur Stoll from ergot, a grain fungus that typically grows on rye. The short form "LSD" comes from its early code name LSD-25, which is an abbreviation for the German "Lysergsäure-diethylamid" followed by a sequential number.[6][7] LSD is sensitive to oxygen, ultraviolet light, and chlorine,[7] especially in solution, though its potency may last for years if it is stored away from light and moisture at low temperature. In pure form it is a colorless, odorless, tasteless solid.[8] LSD is typically either swallowed (oral) or held under the tongue (sublingual), usually on a substrate such as absorbent blotter paper, a sugar cube, or gelatin. In its liquid form, it can also be administered by intramuscular or intravenous injection. Interestingly, unlike most other classes of illicit drugs and other groups of psychedelic drugs such as tryptamines and phenethylamines, when LSD is administered via intravenous injection the onset is not immediate, instead taking approximately 30 minutes before the effects are realized. LSD is very potent, with 20–30 µg (micrograms) being the threshold dose.[9]

Hofmann discovered the psychedelic properties of LSD in 1943.[10] It was introduced commercially in 1947 by Sandoz Laboratories under the trade-name Delysid as a drug with various psychiatric uses, and it quickly became a therapeutic agent that appeared to show great promise.[11] In the 1950s, officials at the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) thought the drug might be applicable to mind control and chemical warfare; the agency's MKULTRA research program propagated the drug among young servicemen and students. The subsequent recreational use of the drug by youth culture in the Western world during the 1960s led to a political firestorm that resulted in its prohibition.[12] Currently, a number of organizations—including the Beckley Foundation, MAPS, Heffter Research Institute and the Albert Hofmann Foundation—exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into the medicinal and spiritual uses of LSD and related psychedelics.[13] New clinical LSD experiments in humans started in 2009 for the first time in 35 years.[14]

Effects

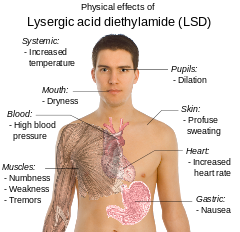

Physical

LSD can cause pupil dilation, reduced appetite, and wakefulness. Other physical reactions to LSD are highly variable and nonspecific, some of which may be secondary to the psychological effects of LSD. Among the reported symptoms are numbness, weakness, nausea, hypothermia or hyperthermia, elevated blood sugar, goose bumps, heart rate increase, jaw clenching, perspiration, saliva production, mucus production, sleeplessness, hyperreflexia, and tremors. Some users, including Albert Hofmann, report a strong metallic taste for the duration of the effects.[15]

LSD is not considered addictive by the medical community.[4] Tolerance to LSD-25 builds up over consistent use[16] and cross-tolerance has been demonstrated between LSD, mescaline[17] and psilocybin.[18] This tolerance diminishes after a few days after cessation of use and is probably caused by downregulation of 5-HT2A receptors in the brain.[19][20]

Psychological

LSD's psychological effects (colloquially called a "trip") vary greatly from person to person, depending on factors such as previous experiences, state of mind and environment, as well as dose strength. They also vary from one trip to another, and even as time passes during a single trip. An LSD trip can have long-term psychoemotional effects; some users cite the LSD experience as causing significant changes in their personality and life perspective.[21] Widely different effects emerge based on what Timothy Leary called set and setting; the "set" being the general mindset of the user, and the "setting" being the physical and social environment in which the drug's effects are experienced.

Some psychological effects may include an experience of radiant colors, objects and surfaces appearing to ripple or "breathe", colored patterns behind the closed eyelids (eidetic imagery), an altered sense of time (time seems to be stretching, repeating itself, changing speed or stopping), crawling geometric patterns overlaying walls and other objects, morphing objects, a sense that one's thoughts are spiraling into themselves, loss of a sense of identity or the ego (known as "ego death"), and other powerful psycho-physical reactions.[22] Many users experience a dissolution between themselves and the "outside world".[23] This unitive quality may play a role in the spiritual and religious aspects of LSD. The drug sometimes leads to disintegration or restructuring of the user's historical personality and creates a mental state that some users report allows them to have more choice regarding the nature of their own personality.

If the user is in a hostile or otherwise unsettling environment, or is not mentally prepared for the powerful distortions in perception and thought that the drug causes, effects are more likely to be unpleasant than if he or she is in a comfortable environment and has a relaxed, balanced and open mindset.[24]

Sensory

LSD causes an animated sensory experience of senses, emotions, memories, time, and awareness for 6 to 14 hours, depending on dosage and tolerance. Generally beginning within 30 to 90 minutes after ingestion, the user may experience anything from subtle changes in perception to overwhelming cognitive shifts. Changes in auditory and visual perception are typical.[23][25] Visual effects include the illusion of movement of static surfaces ("walls breathing"), after image-like trails of moving objects ("tracers"), the appearance of moving colored geometric patterns (especially with closed eyes), an intensification of colors and brightness ("sparkling"), new textures on objects, blurred vision, and shape suggestibility. Users commonly report that the inanimate world appears to animate in an inexplicable way; for instance, objects that are static in three dimensions can seem to be moving relative to one or more additional spatial dimensions.[26] Many of the basic visual effects resemble the phosphenes seen after applying pressure to the eye and have also been studied under the name "form constants". The auditory effects of LSD may include echo-like distortions of sounds, changes in ability to discern concurrent auditory stimuli, and a general intensification of the experience of music. Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental distortions of sensory perception such as synaesthesia, the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions, and temporary dissociation.

Potential uses

LSD has been used in psychiatry for its perceived therapeutic value, in the treatment of alcoholism, pain and cluster headache relief, for spiritual purposes, and to enhance creativity. However, government organizations like the United States Drug Enforcement Administration maintain that LSD "produces no aphrodisiac effects, does not increase creativity, has no lasting positive effect in treating alcoholics or criminals, does not produce a 'model psychosis', and does not generate immediate personality change."[27]

Therapies

Psychedelic therapy

In the 1950s and 1960s LSD was used in psychiatry to enhance psychotherapy known as psychedelic therapy. Some psychiatrists believed LSD was especially useful at helping patients to "unblock" repressed subconscious material through other psychotherapeutic methods,[28] and also for treating alcoholism.[29][30] One study concluded, "The root of the therapeutic value of the LSD experience is its potential for producing self-acceptance and self-surrender,"[31] presumably by forcing the user to face issues and problems in that individual's psyche.

In December 1968, a survey was made of all 74 UK doctors who had used LSD in humans; 73 replied, 1 had moved overseas and was unavailable. The majority of UK doctors with clinical experience with LSD felt that LSD was effective and had acceptable safety:

- 56% (41) continued with clinical use of LSD

- 15% (11) had stopped because of retirement or other extraneous reasons

- 12% (9) had stopped because they found LSD ineffective

- 10% (7) had stopped for unspecified reasons

- 7% (5) had stopped because they felt LSD was too dangerous[32]

End-of-life anxiety

Since 2008 there has been ongoing research in Switzerland into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for terminally ill cancer patients coping with their impending deaths. Preliminary results from the study are promising, and no negative effects have been reported.[33][34][35]

Alcoholism treatment

Some studies in the 1960s that used LSD to treat alcoholism reduced levels of alcohol misuse in almost 60% of those treated, an effect which lasted six months but disappeared after a year.[36][37] A 1998 review was inconclusive.[38] However, a 2012 meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials found evidence that a single dose of LSD in conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs was associated with a decrease in alcohol abuse, lasting for several months.[39]

Pain management

LSD was studied in the 1960s by Eric Kast for pain management as an analgesic for serious and chronic suffer caused by cancer or other major trauma.[40] Even at low (sub-psychedelic) dosages, it was found to be at least as effective as traditional opiates, while being much longer lasting in pain reduction (lasting as long as a week after peak effects had subsided). Kast attributed this effect to a decrease in anxiety; that is to say that patients were not experiencing less pain, but rather were less distressed by the pain they experienced. This reported effect is being tested (though not using LSD) in an ongoing (as of 2006) study of the effects of psilocybin on anxiety in terminal cancer patients.

Cluster headaches

LSD has been used as a treatment for cluster headaches, an uncommon but extremely painful disorder which researcher Peter Goadsby describes as "worse than natural childbirth or even amputation without anesthetic."[41] Although the phenomenon has not been formally investigated, case reports indicate that LSD and psilocybin can reduce cluster pain and also interrupt the cluster-headache cycle, preventing future headaches from occurring. Currently existing treatments include various ergolines, among other chemicals, so LSD's efficacy may not be surprising. A dose-response study testing the effectiveness of both LSD and psilocybin was planned at McLean Hospital, although the current status of this project is unclear. A 2006 study by McLean researchers interviewed 53 cluster-headache sufferers who treated themselves with either LSD or psilocybin, finding that a majority of the users of either drug reported beneficial effects.[42] Unlike use of LSD or MDMA in psychotherapy, this research involves non-psychological effects and often sub-psychedelic dosages.[43][44]

Entheogen

LSD is considered an entheogen because it can catalyze intense spiritual experiences, during which users may feel they have come into contact with a greater spiritual or cosmic order. Users claim to experience lucid sensations where they have "out of body" experiences. Some users report insights into the way the mind works, and some experience permanent shifts in their life perspective. LSD also allows users to view their life from an introspective point of view. Some users report using introspection to resolve unresolved or negative feelings towards an individual or incident that occurred in the past. Some users consider LSD a religious sacrament, or a powerful tool for access to the divine. Stanislav Grof has written that religious and mystical experiences observed during LSD sessions appear to be phenomenologically indistinguishable from similar descriptions in the sacred scriptures of the great religions of the world and the secret mystical texts of ancient civilizations.[45]

Creativity

In the 1950s and 1960s, psychiatrists like Oscar Janiger explored the potential effect of LSD on creativity. Experimental studies attempted to measure the effect of LSD on creative activity and aesthetic appreciation.[46][47][48][49] Seventy professional artists were asked to draw two pictures of a Hopi Indian kachina doll, one before ingesting LSD and one after.[50]

Potential adverse effects

There are no human deaths documented from an LSD overdose.[51] It is physiologically well tolerated and there is no evidence for long-lasting physiological effects on the brain or other parts of the human organism.[52]

LSD can temporarily impair the ability to fully understand common dangers and therefore lack awareness to make appropriate judgments -thus making the user more susceptible to personal injury and accidents. It may cause temporary confusion, difficulty with abstract thinking, or signs of impaired memory and attention span.[53] For example, self-inflicted testicular amputation has been noted in medical literature as a result of concurrent LSD and alcohol use.[54][55]

Adverse drug interactions

Mental disorders

LSD may trigger panic attacks or feelings of extreme anxiety, colloquially referred to as a "bad trip". No real prolonged effects have been proven; however, there is some evidence that people with such conditions as schizophrenia can worsen with LSD.[56]

Suggestibility

While publicly available documents indicate that the CIA and Department of Defense have discontinued research into the use of LSD as a means of mind control,[57] research from the 1960s suggests there exists evidence that both mentally ill and healthy people are more suggestible while under its influence.[58][59]

Psychosis

Historical data suggests that there has been the occasional incidence of LSD induced psychosis in people who appeared to be healthy prior to taking the drug.[60]

Estimates of the prevalence of LSD-induced psychosis diagnosed by surveying researchers and therapists who had administered LSD are given in two early papers.

- Cohen (1960) analysed data from 44 practitioners who had administered LSD and estimated 0.8 per 1,000 volunteers (a single case out of 1,250, where the volunteer was the identical twin of a person with schizophrenia) and 1.8 per 1,000 psychiatric patients (7 cases among approximately 3850 patients).[61]

- Malleson (1971) reported no cases of psychosis among experimental subjects (170 volunteers) and estimated 9 per 1,000 among psychiatric patients (37 cases among 4300 patients).[32]

This data comes with several limitations, the first being that many of the psychiatric patients who were given LSD had severe mental health issues (inpatients) so the results cannot be used to make conclusions about the general population. Secondly, it was not possible to verify whether the psychosis was in fact due to LSD administration, external variables or a combination of both and this is further confounded by the lack of control groups (no LSD) from which to make a comparison. Cohen (1960) noted that many subsequent disturbances had been attributed to LSD without any further justification and individuals would tend to focus on their LSD experience to explain any subsequent illness including migraines and attacks of influenza that occurred up to a year later.[61] He concluded that

This inquiry into the adverse effects of the hallucinogenic drugs indicates that with proper precautions they are safe when given to a selected healthy group. Their use in patients [psychiatric inpatients] has been associated with an occasional complication.

The most recent data collected by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse), summarized results, comparing those who used psychedelic drugs to a population who had not, from 130,152 respondents (of the psychedelic drug users, 17,486 of 21,967 respondents accounting for 80% of the cohort had used LSD). They found that there was no association between psychedelic drug use and mental health problems in later life and if anything there was a trend suggesting that psychedelic drug users had a lower risk of a mental health problems than the control group.[62]

Flashbacks and HPPD

"Flashbacks" are a reported psychological phenomenon in which an individual experiences an episode of some of LSD's subjective effects long after the drug has worn off, usually in the days after typical doses. In some rarer cases, flashbacks have lasted longer, but are generally short-lived and mild compared to the actual LSD "trip". Flashbacks can incorporate both positive and negative aspects of LSD trips, and are typically elicited by triggers such as alcohol or cannabis use, stress, caffeine, or sleepiness. Flashbacks have proven difficult to study and are no longer officially recognized as a psychiatric syndrome. However, colloquial usage of the term persists and usually refers to any drug-free experience reminiscent of psychedelic drug effects, with the typical connotation that the episodes are of short duration.

No definitive explanation is currently available for these experiences. Any attempt at explanation must reflect several observations: first, over 70 percent of LSD users claim never to have "flashed back"; second, the phenomenon does appear linked with LSD use, though a causal connection has not been established; and third, a higher proportion of psychiatric patients report flashbacks than other users.[63] Several studies have tried to determine how likely a user of LSD, not suffering from known psychiatric conditions, is to experience flashbacks. The larger studies include Blumenfeld's in 1971[64] and Naditch and Fenwick's in 1977,[65] which arrived at figures of 20% and 28%, respectively. Interestingly, the experiments by Sidney Cohen in 1960 did not report a single "flashback" phenomenon.[66]

Although flashbacks themselves are not recognized as a medical syndrome, there is a recognized syndrome called Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) in which LSD-like visual changes are not temporary and brief, as they are in flashbacks, but instead are persistent, and cause clinically significant impairment or distress. The syndrome is a DSM-IV diagnosis. Several scientific journal articles have described the disorder.[67]

HPPD differs from flashbacks in that it is persistent and apparently entirely visual (although mood and anxiety disorders are sometimes diagnosed in the same individuals). A recent review suggests that HPPD (as defined in the DSM-IV) is rare and affects only a distinctly vulnerable subpopulation of users.[68] However, it is possible that the prevalence of HPPD is underestimated because most of the diagnoses are applied to people who are willing to admit to their health care practitioner that they have previously used psychotropics, and presumably many people are reluctant to admit this.[69]

There is no consensus regarding the nature and causes of HPPD (or flashbacks). A study of 44 HPPD subjects who had previously ingested LSD showed EEG abnormalities.[70] Given that some symptoms have environmental triggers, it may represent a failure to adjust visual processing to changing environmental conditions. There are no explanations for why only some individuals develop HPPD. Explanations in terms of LSD physically remaining in the body for months or years after consumption have been discounted by experimental evidence.[63] Some say HPPD is a manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder, not related to the direct action of LSD on brain chemistry, and varies according to the susceptibility of the individual to the disorder. Many emotionally intense experiences can lead to flashbacks when a person is reminded acutely of the original experience. However, not all published case reports of HPPD appear to describe an anxious hyper-vigilant state reminiscent of post-traumatic stress disorder. Instead, some cases appear to involve only visual symptoms.[63]

Uterine contractions

Early pharmacological testing by Sandoz in laboratory animals showed that LSD can stimulate uterine contractions, with efficacy comparable to ergobasine, the active uterotonic component of the ergot fungus. (Hofmann's work on ergot derivatives also produced a modified form of ergobasine which became a widely accepted medication used in obstetrics, under the trade name Methergine.) Therefore, LSD use by pregnant women could be dangerous and is contraindicated.[6] However, the relevance of these animal studies to humans is unclear, and a 2008 medical reference guide to drugs in pregnancy and lactation stated, "It appears unlikely that pure LSD administered in a controlled condition is an abortifacient."[71]

Genetic

In 1967, a report concluded that the addition of LSD to human leukocytes caused an increase in chromosomal damage.[72] This report did not however, withstand the test of time and this was disproved in later studies.[73] In 1969 Moseley, working under Edward Pauling showed that therapeutically high doses of LSD actually reduced chromosomal breakage."[71] Further research using empirical evidence also found that there was no evidence of chromosomal abnormalities with LSD use.[74] In 1980 a study of the existing literature concluded that there was no evidence of chromosomal damage, no mutagenic effects, no teratogenic effects and that LSD has no carcinogenic potential, and this is still the scientific consensus today.[75]

Alteration of gene expression

Chronic administration of LSD alters gene expression profiles in the medial prefrontal cortex. Evidence form studies in rodents demonstrates that chronic LSD affects the expression of DRD2, GABRB1, NR2A, Krox20, ATP5D, NDUFA1, NPY, and BDNF, among others.[citation needed] Many processes identified as altered by chronic LSD are also implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.[76]

Treatment of intoxication

Reassurance in a calm, safe environment is beneficial. Agitation can be safely addressed with benzodiazepines such as diazepam. Neuroleptics such as haloperidol reduce hallucinations and paranoid delusions and can be used to terminate the effects of LSD. LSD is rapidly absorbed, so activated charcoal and emptying of the stomach will be of little benefit. Sedation or physical restraint is rarely required, and excessive restraint may cause complications such as hyperthermia (over-heating) or rhabdomyolysis.[77]

Massive doses require supportive care,[citation needed] which may include endotracheal intubation or respiratory support. High blood pressure, tachycardia (rapid heart-beat) and hyperthermia, if present, should be treated symptomatically. Treat low blood pressure initially with fluids and then with pressors if necessary. Intravenous administration of anticoagulants, vasodilators, and sympatholytics may be useful with massive doses.

Chemistry and structure

LSD is a chiral compound with two stereocenters at the carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, so that theoretically four different optical isomers of LSD could exist. LSD, also called (+)-D-LSD, has the absolute configuration (5R,8R). The C-5 isomers of lysergamides do not exist in nature and are not formed during the synthesis from D-lysergic acid. Retrosynthetically, the C-5 stereocenter could be analysed as having the same configuration of the alpha carbon of the naturally occurring amino acid L-tryptophan, the precursor to all biosynthetic ergoline compounds.

However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of bases, as the alpha proton is acidic and can be deprotonated and reprotonated. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be separated by chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD.

Pure salts of LSD are triboluminescent, emitting small flashes of white light when shaken in the dark.[7] LSD is strongly fluorescent and will glow bluish-white under UV light.

Synthesis

LSD is an ergoline derivative. It is commonly synthesised by reacting diethylamine with an activated form of lysergic acid. Activating reagents include phosphoryl chloride[78] and peptide coupling reagents.[79] Lysergic acid is made by alkaline hydrolysis of lysergamides like ergotamine, a substance usually derived from the ergot fungus on agar plate, or theoretically possible, but impractical and uncommon from ergine (lysergic acid amide, LSA) extracted from morning glory seeds.[80] Lysergic acid can also be produced synthetically, eliminating the need for ergotamines.[81][82]

Reactivity and degradation

"LSD," writes the chemist Alexander Shulgin, "is an unusually fragile molecule...As a salt, in water, cold, and free from air and light exposure, it is stable indefinitely."[7]

LSD has two labile protons at the tertiary stereogenic C5 and C8 positions, rendering these centres prone to epimerisation. The C8 proton is more labile due to the electron-withdrawing carboxamide attachment, but removal of the chiral proton at the C5 position (which was once also an alpha proton of the parent molecule tryptophan) is assisted by the inductively withdrawing nitrogen and pi electron delocalisation with the indole ring.[citation needed]

LSD also has enamine-type reactivity because of the electron-donating effects of the indole ring. Because of this, chlorine destroys LSD molecules on contact; even though chlorinated tap water contains only a slight amount of chlorine, the small quantity of compound typical to an LSD solution will likely be eliminated when dissolved in tap water.[7] The double bond between the 8-position and the aromatic ring, being conjugated with the indole ring, is susceptible to nucleophilic attacks by water or alcohol, especially in the presence of light. LSD often converts to "lumi-LSD", which is inactive in human beings.[7]

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples.[83] The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD concentration at 25 °C for up to four weeks. After four weeks of incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 °C and up to a 40% at 45 °C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this process can be avoided by the addition of EDTA.

Dosage

A single dose of LSD may be between 40 and 500 micrograms—an amount roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand. Threshold effects can be felt with as little as 25 micrograms of LSD.[9][84] Dosages of LSD are measured in micrograms (µg), or millionths of a gram. By comparison, dosages of most drugs, both recreational and medicinal, are measured in milligrams (mg), or thousandths of a gram. For example, an active dose of mescaline, roughly 0.2 to 0.5 g, has effects comparable to 100 µg or less of LSD.[6]

In the mid-1960s, the most important black market LSD manufacturer (Owsley Stanley) distributed acid at a standard concentration of 270 µg.[85] While street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 µg. By the 1980s, the amount had reduced to between 100 and 125 µg, lowering more in the 1990s to the 20–80 µg range,[86] and even more in the 2000s (decade).[85] [87]

Estimates for the median lethal dose (LD50) of LSD range from 200 µg/kg to more than 1 mg/kg of human body mass, though most sources report that there are no known human cases of such an overdose. Other sources note one report of a suspected fatal overdose of LSD occurring in November 1975 in Kentucky in which there were indications that ~1/3 of a gram (320 mg or 320,000 µg) had been injected intravenously. (This is a very extraordinary amount, equivalent to over 3,000 times the average LSD dosage of ~100 µg).[88][89] Experiments with LSD have also been done on animals; in 1962, an elephant named Tusko died shortly after being injected with 297 mg, but whether the LSD was the cause of his death is controversial (due, in part, to a plethora of other chemical substances administered simultaneously).[90]

Pharmacokinetics

LSD's effects normally last from 6–12 hours depending on dosage, tolerance, body weight and age.[7] The Sandoz prospectus for "Delysid" warned: "intermittent disturbances of affect may occasionally persist for several days."[6] Contrary to early reports and common belief, LSD effects do not last longer than the amount of time significant levels of the drug are present in the blood. Aghajanian and Bing (1964) found LSD had an elimination half-life of only 175 minutes.[2] However, using more accurate techniques, Papac and Foltz (1990) reported that 1 µg/kg oral LSD given to a single male volunteer had an apparent plasma half-life of 5.1 hours, with a peak plasma concentration of 5 ng/mL at 3 hours post-dose.[3]

Detection in biological fluids

LSD may be quantified in urine as part of a drug abuse testing program, in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized victims or in whole blood to assist in a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a case of sudden death. Both the parent drug and its major metabolite are unstable in biofluids when exposed to light, heat or alkaline conditions and therefore specimens are protected from light, stored at the lowest possible temperature and analyzed quickly to minimize losses.[91]

Pharmacodynamics

LSD affects a large number of the G protein-coupled receptors, including all dopamine receptor subtypes, and all adrenoreceptor subtypes, as well as many others.[citation needed] Most serotonergic psychedelics are not significantly dopaminergic, and LSD is therefore rather unique in this regard. LSD's agonism of D2 receptors contributes to its psychoactive effects.[92][93] LSD binds to most serotonin receptor subtypes except for 5-HT3 and 5-HT4. However, most of these receptors are affected at too low affinity to be sufficiently activated by the brain concentration of approximately 10–20 nM.[94] In humans, recreational doses of LSD can affect 5-HT1A (Ki=1.1nM), 5-HT2A (Ki=2.9nM), 5-HT2B (Ki=4.9nM), 5-HT2C (Ki=23nM), 5-HT5A (Ki=9nM [in cloned rat tissues]), and 5-HT6 receptors (Ki=2.3nM).[2][95] 5-HT5B receptors, which are not present in humans, also have a high affinity for LSD.[96] The psychedelic effects of LSD are attributed to cross-activation of 5-HT2A receptor heteromers.[97] Many but not all 5-HT2A agonists are psychedelics and 5-HT2A antagonists block the psychedelic activity of LSD. LSD exhibits functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A and 5HT2C receptors in that it activates the signal transduction enzyme phospholipase A2 instead of activating the enzyme phospholipase C as the endogenous ligand serotonin does.[98] Exactly how LSD produces its effects is unknown, but it is thought that it works by increasing glutamate release in the cerebral cortex[94] and therefore excitation in this area, specifically in layers IV and V.[99] LSD, like many other drugs, has been shown to activate DARPP-32-related pathways.[100]

LSD enhances dopamine D2R protomer recognition and signaling of D2–5-HT2A receptor complexes. This mechanism may contribute to the psychotic actions of LSD.[101]

History

"... affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away."

Albert Hofmann, on his first experience with LSD[102]

LSD was first synthesized on November 16, 1938[103] by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland as part of a large research program searching for medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives. LSD's psychedelic properties were discovered 5 years later when Hofmann himself accidentally ingested an unknown quantity of the chemical.[104] The first intentional ingestion of LSD occurred on April 19, 1943,[105] when Hofmann ingested 250 µg of LSD. He said this would be a threshold dose based on the dosages of other ergot alkaloids. Hofmann found the effects to be much stronger than he anticipated.[106] Sandoz Laboratories introduced LSD as a psychiatric drug in 1947.[107]

Beginning in the 1950s the US Central Intelligence Agency began a research program code named Project MKULTRA. Experiments included administering LSD to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public in order to study their reactions, usually without the subject's knowledge. The project was revealed in the US congressional Rockefeller Commission report in 1975.

In 1963 the Sandoz patents expired on LSD.[86] Also in 1963, the US Food and Drug Administration classified LSD as an Investigational New Drug, which meant new restrictions on medical and scientific use.[86] Several figures, including Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Al Hubbard, began to advocate the consumption of LSD. LSD became central to the counterculture of the 1960s.[108] On October 24, 1968, possession of LSD was made illegal in the United States.[109] The last FDA approved study of LSD in patients ended in 1980, while a study in healthy volunteers was made in the late 1980s. Legally approved and regulated psychiatric use of LSD continued in Switzerland until 1993.[110] Today, medical research is resuming around the world.[14]

Production

An active dose of LSD is very minute, allowing a large number of doses to be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw material. Twenty five kilograms of precursor ergotamine tartrate can produce 5–6 kg of pure crystalline LSD; this corresponds to 100 million doses. Because the masses involved are so small, concealing and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling other illegal drugs like cocaine or cannabis.[111]

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of organic chemistry. It takes two to three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound. It is believed that LSD is not usually produced in large quantities, but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the loss of precursor chemicals in case a step does not work as expected.[111]

Forms

LSD is produced in crystalline form and then mixed with excipients or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is either distributed in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change to tablet form. Appearing in 1968 as an orange tablet measuring about 6 mm across, "Orange Sunshine" acid was the first largely available form of LSD after its possession was made illegal. Tim Scully, a prominent chemist, made some of it, but said that most "Sunshine" in the USA came by way of Ronald Stark, who imported approximately thirty-five million doses from Europe.[112]

Over a period of time, tablet dimensions, weight, shape and concentration of LSD evolved from large (4.5–8.1 mm diameter), heavyweight (≥150 mg), round, high concentration (90–350 µg/tab) dosage units to small (2.0–3.5 mm diameter) lightweight (as low as 4.7 mg/tab), variously shaped, lower concentration (12–85 µg/tab, average range 30–40 µg/tab) dosage units. LSD tablet shapes have included cylinders, cones, stars, spacecraft, and heart shapes. The smallest tablets became known as "Microdots".[113]

After tablets came "computer acid" or "blotter paper LSD", typically made by dipping a preprinted sheet of blotting paper into an LSD/water/alcohol solution.[112][113] More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and more than 350 blotter paper designs have been observed since 1975.[113] About the same time as blotter paper LSD came "Windowpane" (AKA "Clearlight"), which contained LSD inside a thin gelatin square a quarter of an inch (6 mm) across.[112] LSD has been sold under a wide variety of often short-lived and regionally restricted street names including Acid, Trips, Uncle Sid, Blotter, Lucy, Alice and doses, as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper.[114][115] Authorities have encountered the drug in other forms—including powder or crystal, and capsule.[116]

Modern distribution

LSD manufacturers and traffickers in the United States can be categorized into two groups: A few large-scale producers, and an equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale, can be found throughout the country.[117] As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the Drug Enforcement Administration than the larger groups, as their product reaches only local markets.[118]

Mimics

Since 2005, law enforcement in the United States and elsewhere has seized several chemicals and combinations of chemicals in blotter paper which were sold as LSD mimics, including DOB,[119][120] a mixture of DOC and DOI,[121] 25I-NBOMe,[122] and a mixture of DOC and DOB.[123] Street users of LSD are often under the impression that blotter paper which is actively hallucinogenic can only be LSD because that is the only chemical with low enough doses to fit on a small square of blotter paper. While it is true that LSD requires lower doses than most other hallucinogens, blotter paper is capable of absorbing a much larger amount of material. The DEA performed a chromatographic analysis of blotter paper containing 2C-C which showed that the paper contained a much greater concentration of the active chemical than typical LSD doses, although the exact quantity was not determined.[124] Blotter LSD mimics can have relatively small dose squares; a sample of blotter paper containing DOC seized by Concord, California police had dose markings approximately 6 mm apart.[125]

Legal status

Template:Globalize/Eng The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (adopted in 1971) requires its parties to prohibit LSD. Hence, it is illegal in all parties to the convention, which includes the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Europe. However, enforcement of extant laws varies from country to country. Medical and scientific research with LSD in humans is permitted under the 1971 UN Convention.[126]

Canada

In Canada, LSD is a controlled substance under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[127] Every person who seeks to obtain the substance, without disclosing authorization to obtain such substances 30 days before obtaining another prescription from a practitioner, is guilty of an indictable offense and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 3 years. Possession for purpose of trafficking is an indictable offense punishable by imprisonment for 10 years.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, LSD is a Schedule 1 Class 'A' drug. This means it has no recognised legitimate uses and possession of the drug without a license is punishable with 7 years imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine, and trafficking is punishable with life imprisonment and an unlimited fine (see main article on drug punishments Misuse of Drugs Act 1971).

In 2000, after consultation with members of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Faculty of Substance Misuse, the UK Police Foundation issued the Runciman Report which recommended "the transfer of LSD from Class A to Class B".[128]

In November 2009, the UK Transform Drug Policy Foundation released in the House of Commons a guidebooks to the legal regulation of drugs, After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation, which details options for regulated distribution and sale of LSD and other psychedelics.[129]

United States

LSD is Schedule I in the United States, according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.[130] This means LSD is illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute without a DEA license. By classifying LSD as a Schedule I substance, the Drug Enforcement Administration holds that LSD meets the following three criteria: it is deemed to have a high potential for abuse; it has no legitimate medical use in treatment; and there is a lack of accepted safety for its use under medical supervision. There are no documented deaths from chemical toxicity; most LSD deaths are a result of behavioral toxicity.[131]

There can also be substantial discrepancies between the amount of chemical LSD that one possesses and the amount of possession with which one can be charged in the U.S. This is because LSD is almost always present in a medium (e.g. blotter or neutral liquid), and the amount that can be considered with respect to sentencing is the total mass of the drug and its medium. This discrepancy was the subject of 1995 United States Supreme Court case, Neal v. U.S.[132]

Lysergic acid and lysergic acid amide, LSD precursors, are both classified in Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act. Ergotamine tartrate, a precursor to lysergic acid, is regulated under the Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act.

See also

- ALD-52, chemical analogue of LSD

- LSD art, on the effect of LSD on drawing and painting

- Methysergide, headache medication, chemically related to LSD

- Psychedelic experience

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

- Urban legends about LSD

References

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

Several other classes of drugs are categorized as drugs of abuse but rarely produce compulsive use. These include psychedelic agents, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which are used for their ability to produce perceptual distortions at low and moderate doses. The use of these drugs is associated with the rapid development of tolerance and the absence of positive reinforcement (Chapter 6). Partial agonist effects at 5HT2A receptors are implicated in the psychedelic actions of LSD and related hallucinogens. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly called ecstasy, is an amphetamine derivative. It produces a combination of psychostimulant-like and weak LSD-like effects at low doses. Unlike LSD, MDMA is reinforcing—most likely because of its interactions with dopamine systems—and accordingly is subject to compulsive abuse. The weak psychedelic effects of MDMA appear to result from its amphetamine-like actions on the serotonin reuptake transporter, by means of which it causes transporter-dependent serotonin efflux. MDMA has been proven to produce lesions of serotonin neurons in animals and humans.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Aghajanian GK, Bing OH (1964). "Persistence of lysergic acid diethylamide in the plasma of human subjects" (PDF). Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 5: 611–614. PMID 14209776. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Papac DI, Foltz RL (May–June 1990). "Measurement of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in human plasma by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry" (PDF). Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 14 (3): 189–190. doi:10.1093/jat/14.3.189. PMID 2374410. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Lüscher C, Ungless MA (November 2006). "The Mechanistic Classification of Addictive Drugs". PLoS Med. 3 (11): e437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. PMC 1635740. PMID 17105338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A (2008). "The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: a Review" (PDF). CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. PMID 19040555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Hofmann, Albert. LSD—My Problem Child (McGraw-Hill, 1980). ISBN 0-07-029325-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alexander and Ann Shulgin. "LSD", in TiHKAL (Berkeley: Transform Press, 1997). ISBN 0-9630096-9-9.

- ^ Albert Hofmann. "LSD – My Problem Child (English translation)".

- ^ a b Greiner T, Burch NR, Edelberg R (1958). "Psychopathology and psychophysiology of minimal LSD-25 dosage; a preliminary dosage-response spectrum". AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 79 (2): 208–10. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1958.02340020088016. PMID 13497365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hallucinogenic effects of LSD discovered". The History Channel.

- ^ Arthur Stoll and Albert Hofmann LSD Patent April 30, 1943 in Switzerland and March 23, 1948 in the United States.

- ^ "LSD: cultural revolution and medical advances". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ "The Albert Hofmann Foundation". Hofmann Foundation. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b "LSD & Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy for Anxiety". Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ Albert Hofmann. "5. From Remedy to Inebriant". LSD: My Problem Child.

...taste of metal on the palate.

- ^ "Gross behavioural changes in monkeys following administration of LSD-25, and development of tolerance to LSD-25 – Springer". link.springer.com. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Wolbach AB, Isbell H, Miner EJ (1962). "Cross tolerance between mescaline and LSD-25, with a comparison of the mescaline and LSD reactions". Psychopharmacologia. 3: 1–14. doi:10.1007/BF00413101. PMID 14007904.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Isbell H, Wolbach AB, Wikler A, Miner EJ (1961). "Cross Tolerance between LSD and Psilocybin". Psychopharmacologia. 2 (3): 147–59. doi:10.1007/BF00407974. PMID 13717955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McKenna DJ, Nazarali AJ, Himeno A, Saavedra JM (1989). "Chronic treatment with (+/-)DOI, a psychotomimetic 5-HT2 agonist, downregulates 5-HT2 receptors in rat brain". Neuropsychopharmacology. 2 (1): 81–87. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(89)90010-9. PMID 2803482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Buckholtz NS, Zhou DF, Freedman DX, Potter WZ (1990). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) administration selectively downregulates serotonin2 receptors in rat brain". Neuropsychopharmacology. 3 (2): 137–148. PMID 1969270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harris, Sam (2014), "The spiritual uses of pharmacology", Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion, Simon and Schuster, pp. 186–200, ISBN 9781451636017,

I found psilocybin and LSD to be indispensable tools, and some of the most important hours of my life were spent under their influence ... psychedelics ... often reveal, in the span of a few hours, depths of awe and understanding that can otherwise elude us for a lifetime.

- ^ The Good Drugs Guide. "LSD psychedelic effects". Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Linton Harriet B., Langs Robert J. (1962). "Subjective Reactions to Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD-25)" (PDF). Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 6 (5): 352–68. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1962.01710230020003.

- ^ "LSD dangers". The Good Drugs Guide. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Katz MM, Waskow IE, Olsson J (1968). "Characterizing the psychological state produced by LSD". J Abnorm Psychol. 73 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1037/h0020114. PMID 5639999.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See, e.g., Gerald Oster's article "Moiré patterns and visual hallucinations". Psychedelic Rev. No. 7 (1966): 33–40.

- ^ DEA Public Affairs (November 16, 2001). "DEA – Publications – LSD in the US – The Drug". Web.petabox.bibalex.org. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Cohen, S. (1959). The therapeutic potential of LSD-25. A Pharmacologic Approach to the Study of the Mind, p251–258.

- ^ "Use of d-lysergic acid diethylamide in the treatment of alcoholism". Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ "Use of d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in the Treatment of Alcoholism". Hofmann.org. November 14, 2003. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Chwelos N, Blewett DB, Smith CM, Hoffer A (1959). "Use of d-lysergic acid diethylamide in the treatment of alcoholism". Quart. J. Stud. Alcohol. 20: 577–90. PMID 13810249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Malleson N (1971). "Acute Adverse Reactions to LSD in Clinical and Experimental Use in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Br J Psychiatry. 118 (543): 229–30. doi:10.1192/bjp.118.543.229. PMID 4995932.

- ^ "Psychiater Gasser bricht sein Schweigen". July 28, 2009.

- ^ "LSD-Assisted Psychotherapy for Anxiety Associated with Life-Threatening Illness". Maps.org. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ David Jay Brown (May 27, 2011). "Landmark Clinical LSD Study Nears Completion". Patch.com.

- ^ "LSD "helps alcoholics to give up drinking"". BBC. March 9, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ Maclean, J.R.; Macdonald, D.C.; Ogden, F.; Wilby, E., "LSD-25 and mescaline as therapeutic adjuvants." In: Abramson, H., Ed., The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism, Bobbs-Merrill: New York, 1967, pp. 407–426; Ditman, K.S.; Bailey, J.J., "Evaluating LSD as a psychotherapeutic agent," pp.74–80; Hoffer, A., "A program for the treatment of alcoholism: LSD, malvaria, and nicotinic acid," pp. 353–402.

- ^ Mangini M (1998). "Treatment of alcoholism using psychedelic drugs: a review of the program of research". J Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (4): 381–418. doi:10.1080/02791072.1998.10399714. PMID 9924844.

- ^ Krebs TS, Johansen PØ; Johansen, Pal-Orjan (March 8, 2012). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7). Jop.sagepub.com: 994–1002. doi:10.1177/0269881112439253. PMID 22406913. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ Kast E (1967). "Attenuation of anticipation: a therapeutic use of lysergic acid diethylamide" (PDF). Psychiat. Quart. 41 (4): 646–57. doi:10.1007/BF01575629. PMID 4169685.

- ^ Goadsby is quoted in "Research into psilocybin and LSD as cluster headache treatment", and he makes an equivalent statement in an Health Report interview[dead link] on Australian Radio National (August 9, 1999). Pages accessed January 31, 2007.

- ^ Sewell RA, Halpern JH, Pope HG (June 27, 2006). "Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD". Neurology. 66 (12): 1920–2. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219761.05466.43. PMID 16801660.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Summarized from "Research into psilocybin and LSD as cluster headache treatment" and the Clusterbusters website. Pages accessed January 31, 2007.

- ^ Berlin pilot cluster headaches treatment with LSD study. LSD Alleviates 'Suicide Headaches'.

- ^ Grof, Stanislav; Joan Halifax Grof (1979). Realms of the Human Unconscious (Observations from LSD Research). London: Souvenir Press (E & A) Ltd. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-285-64882-9.

- ^ Sessa B (2008). "Is it time to revisit the role of psychedelic drugs in enhancing human creativity?". J Psychopharmacol. 22 (8): 821–7. doi:10.1177/0269881108091597. PMID 18562421.

- ^ Janiger O, Dobkin de Rios M (1989). "LSD and creativity". J Psychoactive Drugs. 21 (1): 129–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.1989.10472150. PMID 2723891.

- ^ Stafford, Peter G.; B. H. Golightly (1967). LSD, the problem-solving psychedelic. ASIN B0006BPSA0.

- ^ McGlothlin W, Cohen S, McGlothlin MS (1967). "Long lasting effects of LSD on normals" (PDF). Archives of General Psychiatry. 17 (5): 521–532. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1967.01730290009002. PMID 6054248.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whalen, John (July 9, 1998). "The Trip: Cary Grant on acid, and other stories from the LSD Studies of Dr. Oscar Janiger". LA Weekly.

- ^ Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A (November 11, 2008). "The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. PMID 19040555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review" (PDF). Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ LSD AND ORGANIC BRAIN IMPAIRMENT S Cohen, AE Edwards – Drug dependence, 1969

- ^ Blacha C, Schmid MM, Gahr M, Freudenmann RW, Plener PL, Finter F, Connemann BJ, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C (2013). "Self-inflicted testicular amputation in first lysergic acid diethylamide use". J Addict Med. 7 (1): 83–4. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e318279737b. PMID 23222128.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "lysergic acid diethylamide (CHEBI:6605)". CHEBI. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "Erowid LSD (Acid) Vaults: Health: Excerpt from Strassman's Adverse Reactions to Psychedelic Drugs". Erowid.org. March 25, 1993. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "Is Military Research Hazardous to Veterans Health? Lessons Spanning Half A Century, part F. HALLUCINOGENS". December 8, 1994 John D. Rockefeller IV, West Virginia: 103rd Congress, 2nd Session-S. Prt. 103-97; Staff Report prepared for the committee on veterans' affairs. December 8, 1994.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Middlefell R (March 1967). "The effects of LSD on body sway suggestibility in a group of hospital patients" (PDF). Br J Psychiatry. 113 (496): 277–80. doi:10.1192/bjp.113.496.277. PMID 6029626.

- ^ Sjoberg BM, Hollister LE (November 1965). "The effects of psychotomimetic drugs on primary suggestibility". Psychopharmacologia. 8 (4): 251–62. doi:10.1007/BF00407857. PMID 5885648.

- ^ Strassman RJ (1984). "Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature". J Nerv Ment Dis. 172 (10): 577–95. doi:10.1097/00005053-198410000-00001. PMID 6384428.

- ^ a b Cohen S (January 1960). "Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: Side Effects and Complications" (PDF). Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 130 (1): 30–40. doi:10.1097/00005053-196001000-00005. PMID 13811003.

- ^ Krebs, Teri; Pal-Orjan Johansen (August 19, 2013). "Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study". PLOS One.

- ^ a b c David Abrahart (1998). "A Critical Review of Theories and Research Concerning Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) and Mental Health" (PDF). Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Blumenfield M (1971). "Flashback phenomena in basic trainees who enter the US Air Force". Military Medicine. 136 (1): 39–41. PMID 5005369.

- ^ Naditch MP, Fenwick S (1977). "LSD flashbacks and ego functioning". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 86 (4): 352–9. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.86.4.352. PMID 757972.

- ^ Edward, Brecher. "The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs (1971): Chapter 51".

- ^ See, for example, Abraham HD, Aldridge AM (1993). "Adverse consequences of lysergic acid diethylamide". Addiction. 88 (10): 1327–34. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02018.x. PMID 8251869.

- ^ Halpern JH, Pope HG (2003). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?". Drug Alcohol Depend. 69 (2): 109–19. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00306-X. PMID 12609692.; Halpern JH (2003). "Hallucinogens: an update". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 5 (5): 347–54. doi:10.1007/s11920-003-0067-4. PMID 13678554.

- ^ Baggott; et al. (2006). "Prevalence of chronic flashbacks in hallucinogen users: a web-based questionnaire" (PDF). Retrieved September 25, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Abraham HD, Duffy FH (1996). "Stable quantitative EEG difference in post-LSD visual disorder by split-half analysis: Evidence for disinhibition". Psychiatry Research. 67 (3): 173–187. doi:10.1016/0925-4927(96)02833-8. PMID 8912957.

- ^ a b Gerald G. Briggs, Roger K. Freeman, Sumner J. Yaffe (2008). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7876-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cohen MM, Marinello MJ, Back N. "Chromosomal Damage in Human Leukocytes Induced by Lysergic Acid Diethylamide". Science. 155 (3768): 1417–1419. doi:10.1126/science.155.3768.1417. PMID 6018505.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dishotsky NI, Loughman WD, Mogar RE, Lipscomb WR (1971). "LSD and genetic damage" (PDF). Science. 172 (3982): 431–40. doi:10.1126/science.172.3982.431. PMID 4994465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robinson JT, Chitham RG, Greenwood RM, Taylor JW (1974). "Chromosome aberrations and LSD". Br J Psychiatry. 125: 238–244. doi:10.1192/bjp.125.3.238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grof, Stanislav (1994) [1980]. "The Effects of LSD on Chromosomes, Genetic Mutation, Fetal Development and Malignancy". LSD Psychotherapy. Alameda, California: Hunter House Publishers. Appendix II. ISBN 0-89793-158-0.

- ^ Martin DA (2014): Neuropharmacology. Epub. PMID 24704148

- ^ Brenner S & Corden TE (March 22, 2012). "LSD Toxicity Treatment & Management". Medscape. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Monte AP, Marona-Lewicka D, Kanthasamy A, Sanders-Bush E, Nichols DE (March 1995). "Stereoselective LSD-like activity in a series of d-lysergic acid amides of (R)- and (S)-2-aminoalkanes". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 38 (6): 958–66. doi:10.1021/jm00006a015. PMID 7699712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nichols DE, Frescas S, Marona-Lewicka D, Kurrasch-Orbaugh DM (September 2002). "Lysergamides of isomeric 2,4-dimethylazetidines map the binding orientation of the diethylamide moiety in the potent hallucinogenic agent N,N-diethyllysergamide (LSD)". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 45 (19): 4344–9. doi:10.1021/jm020153s. PMID 12213075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Erowid Morning Glory Vaults : Extraction of LSA (Method #1)". erowid.org. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01594a039, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01594a039instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ol8022648, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ol8022648instead. - ^ Li Z, McNally AJ, Wang H, Salamone SJ (October 1998). "Stability study of LSD under various storage conditions". J. Anal. Toxicol. 22 (6): 520–5. doi:10.1093/jat/22.6.520. PMID 9788528.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stoll, W.A. (1947). "Ein neues, in sehr kleinen Mengen wirsames Phantastikum". Arch. Neur. 60. Schweiz: 483.

- ^ a b Erowid & Eduardo Hidalgo, Energy Control (Spain) (2009). "LSD Samples Analysis". Erowid. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c Henderson, Leigh A.; Glass, William J. (1994). LSD: Still with us after all these years. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-7879-4379-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fire & Earth Erowid (2003). "LSD Analysis – Do we know what's in street acid?". Erowid. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ "LSD Vault: Dosage". July 6, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ "LSD Toxicity: A Suspected Cause of Death". Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ Erowid & R. Stuart (2002). "LSD Related Death of an Elephant – Controversy surrounding the 1962 death of an elephant after an injection of LSD". Erowid. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 871–874.

- ^ Marona-Lewicka D, Thisted RA, Nichols DE (2005). "Distinct temporal phases in the behavioral pharmacology of LSD: Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated effects in the rat and implications for psychosis". Psychopharmacology. 180 (3): 427–435. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-2183-9. PMID 15723230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nichols, David (November 2012). "The End of a Chemistry Era... Dave Nichols Closes Shop". Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Nichols DE (2004). "Psychotropics". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–81. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. PMID 14761703.

- ^ "PDSP database". Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Nelson DL (February 2004). "5-HT5 receptors". Current drug targets. CNS and neurological disorders. 3 (1): 53–8. doi:10.2174/1568007043482606. PMID 14965244.

- ^ Moreno JL et al (2011): Neurosci Lett., 76. PMID 21276828

- ^ Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, Roth BL, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Miller KJ, Spedding M, Mailman RB (June 27, 2006). "Functional Selectivity and Classical Concepts of Quantitative Pharmacology". JPET. 320 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.104463. PMID 16803859.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BilZ0r. "The Neuropharmacology of Hallucinogens: a technical overview". Erowid, v3.1 (August 2005).

- ^ Svenningsson P, Nairn AC, Greengard P (2005). "DARPP-32 mediates the actions of multiple drugs of abuse". AAPS Journal. 7 (2): E353–E360. doi:10.1208/aapsj070235. PMC 2750972. PMID 16353915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Borroto-Escuela DO et al (2014): Biochem Biophys Res Commun., 278. PMID 24309097

- ^ Hofmann 1980, p. 15

- ^ Albert Hofmann; translated from the original German (LSD Ganz Persönlich) by J. Ott. MAPS-Volume 6, Number 69, Summer 1969

- ^ Nichols, David (May 24, 2003). "Hypothesis on Albert Hofmann's Famous 1943 "Bicycle Day"". Hofmann Foundation. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Albert Hofmann. "LSD My Problem Child". Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ Hofmann, Albert. "History Of LSD". Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ DEA Public Affairs (November 16, 2001). "LSD: The Drug". Web.petabox.bibalex.org. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "Brecher, Edward M; et al. (1972). "How LSD was popularized". Consumer Reports/Drug Library". Druglibrary.org. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ United States Congress (October 24, 1968). "Staggers-Dodd Bill, Public Law 90-639" (PDF). Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Gasser, Peter (1994). "Psycholytic Therapy with MDMA and LSD in Switzerland". Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ a b DEA (2007). "LSD Manufacture – Illegal LSD Production". LSD in the United States. U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on August 29, 2007.

- ^ a b c Stafford, Peter (1992). "Chapter 1 – The LSD Family". Psychedelics Encyclopaedia (Third Expanded ed.). Ronin Publishing Inc. p. 62. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- ^ a b c Laing, Richard R.; Barry L. Beyerstein; Jay A. Siegel (2003). "Chapter 2.2 – Forms of the Drug". Hallucinogens: A Forensic Drug Handbook. Academic Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-12-433951-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Honig, David. Frequently Asked Questions via Erowid

- ^ "Street Terms: Drugs and the Drug Trade". Office of National Drug Control Policy. April 5, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ DEA (2008). "Photo Library (page 2)". US Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved June 27, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ ^ Maclean, J.R.; Macdonald, D.C.; Ogden, F.; Wilby, E., "LSD-25 and mescaline as therapeutic adjuvants." In: Abramson, H., Ed., The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism, Bobbs-Merrill: New York, 1967, pp. 407–426; Ditman, K.S.; Bailey, J.J., "Evaluating LSD as a psychotherapeutic agent," pp.74–80; Hoffer, A., "A program for the treatment of alcoholism: LSD, malvaria, and nicotinic acid," pp. 353–402.

- ^ ^ LSD: The Drug

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (October 2005). "LSD BLOTTER ACID MIMIC CONTAINING 4-BROMO-2, 5-DIMETHOXY-AMPHETAMINE (DOB) SEIZED NEAR BURNS, OREGON" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 38 (10). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (November 2006). ""PURPLE" (COUGH SYRUP CONTAINING CODEINE AND OXYCODONE) IN WILKINSBURG, PENNSYLVANIA" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 39 (11). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (March 2008). "UNUSUAL "RICE KRISPIE TREAT"-LIKE BALLS CONTAINING PSILOCYBE MUSHROOM PARTS IN WARREN COUNTY, MISSOURI" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 41 (3). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ Iversen, Les (May 29, 2013). "Temporary Class Drug Order Report on 5-6APB and NBOMe compounds" (PDF). Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Gov.Uk. p. 14. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (March 2009). ""SPICE" – PLANT MATERIAL(S) LACED WITH SYNTHETIC CANNABINOIDS OR CANNABINOID MIMICKING COMPOUNDS" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 42 (3). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (November 2005). "BULK MARIJUANA IN HAZARDOUS PACKAGING IN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 38 (11). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (December 2007). "SMALL HEROIN DISKS NEAR GREENSBORO, GEORGIA" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 40 (12). Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971 Final act of the United Nations Conference

- ^ Canadian government (1996). "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Justice Laws. Canadian Department of Justice. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Drugs and the law: Report of the inquiry into the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 London: Police Foundation, 2000, Runciman Report

- ^ After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation Transform Drug Policy Foundation 2009

- ^ From [1]: LSD is a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act.

- ^ "Toxicity, Hallucinogens – LSD". Emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Neal v. United States, U.S. 284 (1996)., originating from U.S. v. Neal, 46 F.3d 1405 (7th Cir. 1995)

Further reading

- Marks, John. The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control (1979), ISBN 0-8129-0773-6

- Hofmann, Albert. LSD My Problem Child: Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism and Science (1983) ISBN 978-0-9660019-8-3

- Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond (1992) ISBN 978-0-8021-3062-4

- Henderson, Leigh A. and William J. Glass. LSD: Still With Us After All These Years: Based on the National Institute of Drug Abuse Studies on the Resurgence of Contemporary LSD Use (1st edition 1994, 2nd edition 1998) ISBN 978-0-7879-4379-0

- Stevens, Jay. Storming Heaven: LSD And The American Dream (1998) ISBN 978-0-8021-3587-2

- Grof, Stanislav. LSD Psychotherapy. (April 10, 2001)

- de Rios, Marlene Dobkin and Oscar Janiger. LSD, spirituality, and the creative process (2003, Inner Traditions) ISBN 978-0-89281-973-7 – "An exploration of how LSD influences imagination and the creative process. Based on the results of one of the longest clinical studies of LSD that took place between 1954 and 1962, before LSD was illegal. Includes personal reports, artwork, and poetry from the original sessions as testimony of the impact of LSD on the creative process."

- Roberts, Andy. Albion Dreaming: A Popular History of LSD in Britain (2008), Marshall Cavendish, U.K, ISBN 1-905736-27-4

- Bebergal, Peter, "Will Harvard drop acid again? Psychedelic research returns to Crimsonland", The Phoenix (Boston), June 2, 2008

- Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A (2008). "The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x. PMID 19040555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - BBC News: Pont-Saint-Esprit poisoning: Did the CIA spread LSD? (2010)

- Dale Bewan. Dropping Acid: A Beginner's Guide to the Responsible Use of LSD for Self-Discovery (1st edition 2013) ISBN 1492318191

External links

- Drug Profiles: LSD European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- LSD-25 at Erowid

- The Lycaeum Archive: LSD

- LSD entry in TiHKAL • info

- InfoFacts – Hallucinogens NIDA

- Scholarly bibliography on the histories of LSD use

- LSD Returns-For Psychotherapeutics (Scientific American Magazine article)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Lysergic acid diethylamide

- My LSD Trip: a non-cop, non-hippie report of the unvarnished facts, by Robert Gannon, Popular Science Magazine, December 1967.

- WWW Psychedelic Bibliography, MAPS – large database of scientific publications on LSD and other psychedelics, fulltext PDFs

Documentaries

- Hofmann's Potion a documentary on the origins of LSD

- Power & Control LSD in The Sixties on YouTube, documentary film directed by Aron Ranen, 2006

- Inside LSD National Geographic Channel, 2009