Vegetarian cuisine: Difference between revisions

PseudoNova (talk | contribs) Shortened lede by creating separate section for types of vegetarianism. |

PseudoNova (talk | contribs) Added section title for food groups. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[Lacto-ovo vegetarianism]] (the most common type of vegetarianism in the [[Western world]]) includes [[Egg (food)|eggs]] and [[dairy product]]s (such as [[milk]] and cheese without rennet). [[Lacto vegetarianism]] includes dairy products but not eggs, and [[ovo vegetarianism]] encompasses eggs but not dairy products.<ref>{{Cite web|last=|last2=|title=Definitions|url=https://ivu.org/definitions.html|url-status=live|access-date=2021-04-28|website=[[International Vegetarian Union]]|language=en-gb}}</ref> The strictest form of vegetarianism is [[veganism]], which excludes all [[animal product]]s, including dairy, [[honey]], and some refined [[sugar]]s if filtered and whitened with [[bone char]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/becoming-a-vegetarian|title=Becoming a vegetarian|last=Harvard Health Publishing|date=4 December 2017|website=Harvard Health Publishing|access-date=8 October 2018}}</ref> There are also [[Semi-vegetarianism|partial vegetarian]]s, such as [[pescetarian]]s who eat fish but avoid other types of meat.<ref name=":0" /> |

[[Lacto-ovo vegetarianism]] (the most common type of vegetarianism in the [[Western world]]) includes [[Egg (food)|eggs]] and [[dairy product]]s (such as [[milk]] and cheese without rennet). [[Lacto vegetarianism]] includes dairy products but not eggs, and [[ovo vegetarianism]] encompasses eggs but not dairy products.<ref>{{Cite web|last=|last2=|title=Definitions|url=https://ivu.org/definitions.html|url-status=live|access-date=2021-04-28|website=[[International Vegetarian Union]]|language=en-gb}}</ref> The strictest form of vegetarianism is [[veganism]], which excludes all [[animal product]]s, including dairy, [[honey]], and some refined [[sugar]]s if filtered and whitened with [[bone char]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/becoming-a-vegetarian|title=Becoming a vegetarian|last=Harvard Health Publishing|date=4 December 2017|website=Harvard Health Publishing|access-date=8 October 2018}}</ref> There are also [[Semi-vegetarianism|partial vegetarian]]s, such as [[pescetarian]]s who eat fish but avoid other types of meat.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

==Vegetarian food groups== |

|||

There are a wide range of possible vegetarian foods, including some developed to particularly suit a vegetarian/vegan diet, either by filling the culinary niche where recipes would otherwise have meat, or by ensuring healthy intake of [[protein]], [[B12]] vitamin, and other [[nutrient]]s.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Vegetarian diet: How to get the best nutrition - Mayo Clinic|url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/vegetarian-diet/art-20046446?p=1|access-date=2021-04-07|website=www.mayoclinic.org}}</ref> |

There are a wide range of possible vegetarian foods, including some developed to particularly suit a vegetarian/vegan diet, either by filling the culinary niche where recipes would otherwise have meat, or by ensuring healthy intake of [[protein]], [[B12]] vitamin, and other [[nutrient]]s.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Vegetarian diet: How to get the best nutrition - Mayo Clinic|url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/vegetarian-diet/art-20046446?p=1|access-date=2021-04-07|website=www.mayoclinic.org}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:16, 17 June 2023

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

Vegetarian cuisine is based on food that meets vegetarian standards by not including meat and animal tissue products (such as gelatin or animal-derived rennet).[1]

Types of Vegetarianism

Lacto-ovo vegetarianism (the most common type of vegetarianism in the Western world) includes eggs and dairy products (such as milk and cheese without rennet). Lacto vegetarianism includes dairy products but not eggs, and ovo vegetarianism encompasses eggs but not dairy products.[2] The strictest form of vegetarianism is veganism, which excludes all animal products, including dairy, honey, and some refined sugars if filtered and whitened with bone char.[3] There are also partial vegetarians, such as pescetarians who eat fish but avoid other types of meat.[3]

Vegetarian food groups

There are a wide range of possible vegetarian foods, including some developed to particularly suit a vegetarian/vegan diet, either by filling the culinary niche where recipes would otherwise have meat, or by ensuring healthy intake of protein, B12 vitamin, and other nutrients.[4]

- Fish and shellfish.

- Cereals, grains, fungi especially edible mushrooms, seaweed, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts.

- Soy products, including tofu and tempeh, which are common additional protein sources

- Textured vegetable protein (TVP), made from defatted soy flour, often included in chili and burger recipes in place of ground meat.

- Meat analogues, which mimic the taste, texture, and appearance of meat and are often used in recipes that traditionally contained meat.

- Eggs and dairy product analogues in vegan cuisine (such as aquafaba, plant cream or plant milk).

Commonly used vegetarian foods

Food regarded as suitable for all vegetarians (including vegans) typically includes:

- Cereals/grains: barley, buckwheat, corn, fonio, hempseed, maize, millet, oats, quinoa, rice, rye, sorghum, triticale, wheat; derived products such as flour (dough, bread, baked goods, cornflakes, dumplings, granola, Muesli, pasta etc.).

- Vegetables (fresh, canned, frozen, pureed, dried or pickled); derived products such as vegetable sauces like chili sauce and vegetable oils.

- Edible fungi (fresh, canned, dried or pickled). Edible fungi include some mushrooms and cultured microfungi which can be involved in fermentation of food (yeasts and moulds) such as Aspergillus oryzae and Fusarium venenatum, although fungi is rarely considered non-vegetarian due to it not being a plant.

- Fruit (fresh, canned, frozen, pureed, candied or dried); derived products such as jam and marmalade.

- Legumes: beans (including soybeans and soy products such as miso, edamame, soy milk, soy yogurt, tempeh, tofu and TVP), chickpeas, lentils, peas, peanuts; derived products such as peanut butter.

- Tree nuts and seeds; derived products such as nut butter.

- Herbs, spices and wild greens such as dandelion, sorrel or nettle.

- Other foods such as seaweed-derived products such as agar, which has the same function as animal-bone-derived gelatin.

- Beverages such as beer, coffee, hot chocolate, lemonade, tea or wine—although some beers and wines may have elements of animal products as fining agents including fish bladders, egg whites, gelatine and skim milk.

Foods not suitable for vegans, but acceptable for some other types of vegetarians:

- Dairy products (butter, cheese (except for cheese containing rennet of animal origin), milk, yogurt (excluding yogurt made with gelatin) etc.) – not eaten by vegans and pure ovo-vegetarians

- Eggs – not eaten by vegans and lacto-vegetarians (most Indian vegetarians)

- Honey – not eaten by most vegans

Vegetarians by definition cannot consume meat or animal tissue products, with no other universally adopted change in their diet. However, in practice, compared to non-vegetarians, vegetarians on average have an increased consumption of:

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Avocados

- Non-fried potatoes

- Whole grains

- Legumes

- Soy foods

- Nuts

- Seeds

In comparison to non-vegetarians, practising vegetarians on average have a decreased consumption of:

- Dairy products

- Eggs

- Refined grains

- Added fats

- Sweets

- Snacks

- Non-water (often sweetened) beverages

This difference is observed, but is not required to be vegetarian. Nevertheless, it is relevant when considering research into the health effects of adopting a vegetarian diet. A diet consisting only of sugar candies, for example, while technically also vegetarian, would be expected to have a much different outcome for health compared to what is called "a vegetarian diet" culturally and what is most commonly adopted by vegetarians.[5]

Traditional vegetarian cuisine

These are some of the most common dishes that vegetarians eat without substitution of ingredients. Such dishes include, from breakfasts to dinnertime desserts:

- Traditionally, Brahmin cuisines in most part of India, except Jammu and Kashmir, Odisha and West Bengal, are strictly vegetarian. Onion and garlic is not eaten in a strict sattvik diet.

- Gujarati cuisine and Rajasthani cuisine from the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan are predominantly vegetarian.

- Many bean, pasta, potato, rice, and bulgur/couscous dishes, stews, soups and stir-fries.

- Cereals and oatmeals, granola bars, etc.

- Fresh fruit and most salads

- Potato salad, baba ganoush, pita-wraps or burrito -wraps, vegetable pilafs, baked potatoes or fried potato-skins with various toppings, corn on the cob, smoothies

- Many sandwiches, such as cheese on toast, and cold sandwiches including roasted eggplant, mushrooms, bell peppers, cheeses, avocado and other sandwich ingredients

- Numerous side dishes, such as mashed potatoes, scalloped potatoes, some bread stuffings, seasoned rice, and macaroni and cheese.

- Classical Buddhist cuisine in Asia served at temples and restaurants with a green sign indicating vegetarian food only near temples. Onion and garlic is not eaten in a strict Buddhist diet.

National cuisines

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (February 2022) |

- Chinese (and other East Asian) dishes based on the main ingredients being mushroom, noodles, eggplant, string beans, broccoli, rice, tofu, most tong sui or mixed vegetables.

- Georgian cuisine such as ajapsandali, nigvzinai badrijani, badrijnis borani, badrijnis khizilala, badrijani mtsvanilit, ekala nigvzit, ghomi, gogris gupta, khinkali with mushrooms, lobiani, lobio, lobio nigvzit, mchadi, mkhlovani, pkhali, salati nigvzit, shechamandi, shilaplavi, which feature eggplants, walnuts, kidney beans, mushrooms, pomegranates, garlic, squash, onions, tomatoes, cucumbers, bell peppers, chili peppers, beets, fresh herbs (coriander, parsley, basil etc.), smilax, cabbage, spinach, and red/white wine vinegar.

- Indian cuisine in Asia is replete with vegetarian dishes, many of which can be traced to religious traditions (such as Jain and Hindu). Gujarati cuisine of India is predominantly vegetarian among other Indian cuisines: Gujarati thali is very famous among Indians. There are many vegetarian Indian foods such as pakora, samosa, khichris, Pulao, raitas, rasam, bengain bharta, chana masala, some kormas, sambar, jalfrezis, saag aloo, subjis (vegetable dishes) such as bindi subji, gobi subji, Punjabi chole, aloo matar and much South Indian food such as dosas, idlis and vadas. Chapati and other wheat/maida based breads like naan, roti parathas are often stuffed with vegetarian items to make it a satisfying meal. Many Indian dishes also qualify as vegan, though many others use honey or dairy.

- In Indonesia, vegetarianism is well served and represented, as there are plenty selection of vegetarian dishes and meat substitutes. Dishes such as gado-gado, karedok, ketoprak, pecel, urap, rujak and asinan are vegetarian. However, for dishes that use peanut sauce, such as gado-gado, karedok or ketoprak, might contains small amount of shrimp paste for flavor. Served solely, gudeg can be considered a vegetarian food, since it consists of unripe jackfruit and coconut milk. Fermented soy products, such as tempeh, tofu and oncom are prevalent as meat substitutes, as the source of protein. Most of Indonesians do not practice strict vegetarianism and only consume vegetables or vegetarian dishes for their taste, preference, economic and health reasons. Nevertheless, there are small numbers of Indonesian Buddhists who practice vegetarianism for religious reason.

- Japanese foods such as castella, dorayaki, edamame, name kojiru, mochi, taiyaki, tempura, vegetable sushi and wagashi. Miso soup is made from fermented white or red soy bean paste, garnished with scallions or seaweed. Although most traditional versions are made from fish stock (dashi), it can be made with vegetable stock as well.

- Korean cuisine has some dishes that are often vegetarian. One example is bibimbap, which is rice with mixed vegetables. Sometimes this dish contains beef or other non-vegetarian ingredients. Another Korean food which is sometimes vegetarian is jeon, in which ingredients (most commonly vegetables and/or seafood) are coated in a flour and egg batter and then pan-fried in oil.

- Cuisine of the Mediterranean such as tumbet and many polentas and tapas dishes.

- Mexican foods such as salsa and guacamole with chips, rice and bean burritos (without lard in the refried beans or chicken fat in the rice), huevos rancheros, veggie burrito, many quesadillas, bean tacos, some chilaquiles and bean-pies, chili sin carne, black beans with rice, some chiles rellenos, cheese enchiladas and vegetable fajitas.

- Italian foods such as most pastas, many pizzas, bruschetta, caponata, crostini, eggplant parmigiana, Polenta and many risottos.

- Continental cuisine such as braised leeks with olives and parsley, ratatouille, many quiches, sauteed Brussels sprouts with mushrooms, sauteed Swiss chard, squash and vegetable-stuffed mushrooms.

- In Germany, Frankfurt green sauce, Klöße with vegetarian sauces (e.g., Chanterelle), cheese or vegetable stuffed Maultaschen, combinations of quark, spinach, potatoes and herbs provide some traditional vegetarian summer dishes. Traditionally on Fridays, southern Germany broad variety of sweet dishes may be served as a main course, such as Germknödel and Dampfnudel. Potato soup and plum cake are traditional Friday dishes in the Palatinate. Brenntar in Swabia, it is made of roasted flour, usually spelt flour or oat flour.

- Many Greek and Balkan dishes, such as briam, dolmas (when made without minced meat), fasolada, gemista, vegetable based moussaka and spanakopita.

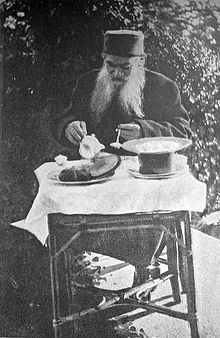

- Russian cuisine developed a significant vegetarian tradition in czarist time, based on the example of Leo Tolstoy.[6] The orthodox tradition of separating meat and vegetables and as well between specific meals for fasting and other holidays contributed to a rich variety of vegetarian dishes[6] in Russia and Slavic countries, such as soups (vegetable borscht, shchi, okroshka), pirogi, blini, vareniki, kasha, buckwheat, fermented and pickled vegetables, etc.

- Many Ethiopian dishes such as injeera or Ethiopian vegetable sauces or chillies.

- Mideastern food such as falafel, hummus (mashed chick peas), tahini (ground sesame seeds), minted-yogurts, and couscous.

- Egyptian cuisine in particular is rich in vegetarian foods. For reasons ranging from economics to the religious practices of the Coptic Orthodox Church, most Egyptian dishes rely on beans and vegetables: the national dishes, kushari and ful medames, are entirely vegetarian, as are usually the assorted vegetable casseroles that characterize the typical Egyptian meal.

- Many dishes in Thai cuisine can be made vegetarian if the main protein element is substituted by a vegetarian alternative such as tofu. This includes dishes such as phat khi mao and, if a vegetarian shrimp paste and fish sauce substitute is used, many Thai curries. Venues serving vegetarian Buddhist cuisine (ahan che; Template:Lang-th) can be found all over Thailand.

- Creole and Southern foods such as hush puppies, okra patties, rice and beans, or sauteed kale or collards, if not cooked with the traditional pork fat or meat stock.

- Some Welsh recipes, including Glamorgan sausages, laverbread and Welsh rarebit.

Desserts and sweets

Most desserts, including pies, cobblers, cakes, brownies, cookies, truffles, Rice Krispie treats (from gelatin-free marshmallows or marshmallow fluff), peanut butter treats, pudding, rice pudding, ice cream, crème brulée, etc., are free of meat and fish and are suitable for ovo-lacto vegetarians. Eastern confectionery and desserts, such as halva and Turkish delight, are mostly vegan, while others such as baklava (which often contains butter) are lacto vegetarian. Indian desserts and sweets are mostly vegetarian like peda, barfi, gulab jamun, shrikhand, basundi, kaju katri, rasgulla, cham cham, rajbhog, etc. Indian sweets are mostly made from milk products and are thus lacto vegetarian; dry fruit-based sweets are vegan.

Meat analogues

A meat alternative or meat substitute (also called plant-based meat, mock meat, or alternative protein),[7] is a food product made from vegetarian or vegan ingredients, eaten as a replacement for meat. Meat alternatives typically approximate qualities of specific types of meat, such as mouthfeel, flavor, appearance, or chemical characteristics.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Plant- and fungus-based substitutes are frequently made with soy (e.g. tofu, tempeh, and textured vegetable protein), but may also be made from wheat gluten as in seitan, pea protein as in the Beyond Burger, or mycoprotein as in Quorn.[14] Alternative protein foods can also be made by precision fermentation, where single cell organisms such as yeast produce specific proteins using a carbon source; as well as cultivated or laboratory grown, based on tissue engineering techniques.[15] The ingredients of meat alternative include 50–80% water, 10–25% textured vegetable proteins, 4–20% non-textured proteins, 0–15% fat and oil, 3-10% flavors/spices, 1-5% binding agents and 0-0.5% coloring agents.[16]

Meatless tissue engineering involves the cultivation of stem cells on natural or synthetic scaffolds to create meat-like products.[17] Scaffolds can be made from various materials, including plant-derived biomaterials, synthetic polymers, animal-based proteins, and self-assembling polypeptides.[18] It is these 3D scaffold-based methods provide a specialized structural environment for cellular growth.[19][20] Alternatively, scaffold-free methods promote cell aggregation, allowing cells to self-organize into tissue-like structures.[21]

Meat alternatives are typically consumed as a source of dietary protein by vegetarians, vegans, and people following religious and cultural dietary laws. However, global demand for sustainable diets has also increased their popularity among non-vegetarians and flexitarians seeking to reduce the environmental impact of animal agriculture.

Meat substitution has a long history. Tofu was invented in China as early as 200 BCE,[22] and in the Middle Ages, chopped nuts and grapes were used as a substitute for mincemeat during Lent.[23] Since the 2010s, startup companies such as Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat have popularized pre-made plant-based substitutes for ground beef, patties, and vegan chicken nuggets as commercial products.Commercial products

Commercial products, marketed especially towards vegetarians and labeled as such, are available in most countries worldwide, in varying amounts and quality. As example, in Australia, various vegetarian products are available in most of supermarket chains and a vegetarian shopping guide is provided by Vegetarian/Vegan Society of Queensland.[24] However, the biggest market for commercially vegetarian-labeled foods is India, with official governmental laws regulating the "vegetarian" and "non vegetarian" labels.

Health benefits

Vegetarian diets are associated with a number of favorable health outcomes in epidemiological studies. In a study supported by a National Institutes of Health grant, dietary patterns were evaluated along with their relationship with metabolic risk factors and metabolic syndromes.[25] A cross-sectional analysis of 773 subjects including 35% vegetarians, 16% semi-vegetarians, and 49% non-vegetarians found that a vegetarian dietary pattern is associated significantly with lower means for all metabolic risk factors except HDL, and a lower risk of metabolic syndromes when compared to non-vegetarian diets. Metabolic risk factors include HDL, triglycerides, glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, waist circumference, and body mass index. Metabolic syndromes are a cluster of disorders associated with a heightened risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Adventist Study 2 (AHS-2) compared mean consumption of each food group for vegetarian patterns compared to non-vegetarian patterns.[5] Health benefits can be explained by increase in certain foods, not just the lack of animal products.

Vegetarian Cuisine is good for the heart as it comprises high-fiber whole grains, nuts, legumes, raw and fresh fruits and vegetables, and other low glycemic foods. Vegetarian Cuisine reduces the risk of cancer as it is a type of animal-free diet. Vegetarian Cuisine also prevents type-2 diabetes and related complications.[26] It is also noticed that people who do not eat meat have chances of having lower blood pressure. This is because vegetables tend to have less fat percentage, low amount of sodium, which positively affects blood pressure. Fruits have a good amount of potassium which helps to keep the blood pressure on the lower side.

As evident by the Adventist Study 2 (AHS-2), the vegetarian diet does not always cause health benefits. This is dependent on the specific foods in the vegetarian diet. The National Institute of Health recommends a 1600 calories a day lacto-ovo vegetarian cuisine for the diet. This recommended diet includes oranges, pancakes, milk, and coffee for breakfast, vegetable soup, bagels, American cheese, and spinach salad for lunch, and omelettes, mozzarella cheese, carrots, whole wheat bread, and tea for dinner.[27]

See also

- Indian vegetarian cuisine

- Chinese Buddhist cuisine

- Korean vegetarian cuisine

- Veganism

- List of meat substitutes

- List of vegetable dishes

- List of vegetarian restaurants

- List of vegetarian and vegan companies

- South Asian Veggie Table – Vegetarian cooking television show

- Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone

- Vegetarian and vegan symbolism

References

- ^ Rosell, Magdalena S.; Appleby, Paul N.; Key, Timothy J. (February 2006). "Health effects of vegetarian and vegan diets". Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 65 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1079/PNS2005481. ISSN 1475-2719. PMID 16441942.

- ^ "Definitions". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Harvard Health Publishing (4 December 2017). "Becoming a vegetarian". Harvard Health Publishing. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Vegetarian diet: How to get the best nutrition - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- ^ a b Orlich, Michael J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, Karen; Sabaté, Joan; Fan, Jing; Singh, Pramil N.; Fraser, Gary E. (November 2014). "Patterns of food consumption among vegetarians and non-vegetarians". British Journal of Nutrition. 112 (10): 1644–1653. doi:10.1017/S000711451400261X. ISSN 0007-1145. PMC 4232985. PMID 25247790.

- ^ a b Peter Brang. Ein unbekanntes Russland, Kulturgeschichte vegetarischer Lebensweisen von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart An ignored aspect of Russia. Vegetarian lifestyles from the very beginning till the present day. Böhlau Verlag, Köln 2002 ISBN 3-412-07902-2

- ^ Lurie-Luke, Elena (2024). "Alternative protein sources: science powered startups to fuel food innovation". Nature Communications. 15: 4425. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47091-0. PMC 11133469.

- ^ van der Weele, Cor; Feindt, Peter; Jan van der Goot, Atze; van Mierlo, Barbara; van Boekel, Martinus (2019). "Meat alternatives: an integrative comparison". Trends in Food Science and Technology. 88: 505–512. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2019.04.018.

- ^ Nezlek, John B; Forestell, Catherine A (2022). "Meat substitutes: current status, potential benefits, and remaining challenges". Current Opinion In Food Science. 47: 100890. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2022.100890.

- ^ Takefuji, Yoshiyasu (2021). "Sustainable protein alternatives". Trends in Food Science and Technology. 107: 429–431. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.11.012.

- ^ Zahari, Izalin; Östbring, Karolina; Purhagen, Jeanette K.; Rayner, Marilyn (2022). "Plant-Based Meat Analogues from Alternative Protein: A Systematic Literature Review". Foods. 11 (18): 2870. doi:10.3390/foods11182870. PMC 9498552. PMID 36140998.

- ^ Lima, Miguel; Costa, Rui; Rodrigues, Ivo; Lameiras, Jorge; Botelho, Goreti (2022). "A Narrative Review of Alternative Protein Sources: Highlights on Meat, Fish, Egg and Dairy Analogues". Foods. 11 (14): 2053. doi:10.3390/foods11142053. PMC 9316106. PMID 35885293.

- ^ Quintieri, Laura; Nitride, Chiara; De Angelis, Elisabetta; Lamonaca, Antonella; Pilolli, Rosa; Russo, Francesco; Monaci, Linda (2023). "Alternative Protein Sources and Novel Foods: Benefits, Food Applications and Safety Issues". Nutrients. 15 (6): 1509. doi:10.3390/nu15061509. PMC 10054669.

- ^ Holmes, Bob (20 July 2022). "How sustainable are fake meats?". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-071922-1. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "All sizzle, no steak: how Singapore became the centre of the plant-based meat industry". The Guardian. 5 November 2022.

- ^ Pang, Shinsiong; Chen, Mu-Chen (April 2024). "Investigating the impact of consumer environmental consciousness on food supply chain: The case of plant-based meat alternatives". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 201: 123190. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123190. ISSN 0040-1625.

- ^ Ahmad, Khurshid; Lim, Jeong-Ho; Lee, Eun-Ju; Chun, Hee-Jin; Ali, Shahid; Ahmad, Syed Sayeed; Shaikh, Sibhghatulla; Choi, Inho (2021-12-15). "Extracellular Matrix and the Production of Cultured Meat". Foods. 10 (12): 3116. doi:10.3390/foods10123116. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 8700801. PMID 34945667.

- ^ Rodrigues, André L.; Rodrigues, Carlos A. V.; Gomes, Ana R.; Vieira, Sara F.; Badenes, Sara M.; Diogo, Maria M.; Cabral, Joaquim M.S. (October 15, 2018). "Dissolvable Microcarriers Allow Scalable Expansion And Harvesting Of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Under Xeno-Free Conditions". Biotechnology Journal. 14 (4): e1800461. doi:10.1002/biot.201800461. ISSN 1860-6768. PMID 30320457.

- ^ Moroni, Lorenzo; Burdick, Jason A.; Highley, Christopher; Lee, Sang Jin; Morimoto, Yuya; Takeuchi, Shoji; Yoo, James J. (2018-04-26). "Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine". Nature Reviews Materials. 3 (5): 21–37. Bibcode:2018NatRM...3...21M. doi:10.1038/s41578-018-0006-y. ISSN 2058-8437. PMC 6586020. PMID 31223488.

- ^ Daly, Andrew C.; Kelly, Daniel J. (January 8, 2019). "Biofabrication of spatially organised tissues by directing the growth of cellular spheroids within 3D printed polymeric microchambers". Biomaterials. 197: 194–206. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.028. hdl:2262/91315. PMID 30660995.

- ^ Alblawi, Adel; Ranjani, Achalla Sri; Yasmin, Humaira; Gupta, Sharda; Bit, Arindam; Rahimi-Gorji, Mohammad (October 20, 2019). "Scaffold-free: A developing technique in field of tissue engineering". Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 185: 105148. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105148. PMID 31678793.

- ^ DuBois, Christine; Tan, Chee-Beng; Mintz, Sidney (2008). The World of Soy. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-9971-69-413-5.

- ^ Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004). Food in Medieval Times. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-313-32147-4.

- ^ Vegetarian/Vegan Society of Queensland. "Vegetarian/Vegan Supermarket Shopping Guide". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Rizzo, Nico S.; Sabaté, Joan; Jaceldo-Siegl, Karen; Fraser, Gary E. (2011-05-01). "Vegetarian Dietary Patterns Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: The Adventist Health Study 2". Diabetes Care. 34 (5): 1225–1227. doi:10.2337/dc10-1221. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC 3114510. PMID 21411506.

- ^ "How and Why to Become a Vegetarian". Healthline. 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- ^ "Lacto-Ovo Vegetarian Cuisine". www.webharvest.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-07.