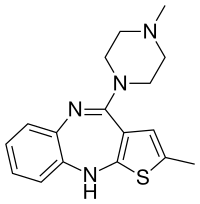

Olanzapine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zyprexa (originator), many generics[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601213 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 87%[3] |

| Protein binding | 93%[4] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (direct glucuronidation and CYP1A2 mediated oxidation) |

| Elimination half-life | 33 hours, 51.8 hours (elderly)[4] |

| Excretion | Urine (57%; 7% as unchanged drug), faeces (30%)[4][5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.320 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H20N4S |

| Molar mass | 312.439 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 195 °C (383 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| | |

Olanzapine (originally branded Zyprexa) is an atypical antipsychotic. It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[6]

Olanzapine is structurally similar to clozapine and quetiapine. It is a dopamine antagonist and is classified as a thienobenzodiazepine. The olanzapine formulations are manufactured and marketed by the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and Company; the drug went generic in 2011. Sales of Zyprexa in 2008 were $2.2B in the US, and $4.7B worldwide.[7]

Medical uses

Schizophrenia

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication which includes olanzapine.[8] A Cochrane review found, however, that the usefulness for maintenance therapy is difficult to determine as more than half of people in trials quit before the six-week completion date.[9]

Comparison

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the British Association for Psychopharmacology, and the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry suggest that there is little difference in effectiveness between antipsychotics in prevention of relapse, and recommend that the specific choice of antipsychotic be chosen based on persons preference and side effect profile.[10][11][12] The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality concludes that olanzapine is not different from haloperidol in the treatment of positive symptoms and general psychopathology, or in overall assessment, but that it is superior for the treatment of negative and depressive symptoms. When trials enrolling only treatment-resistant patients were excluded from the analysis, olanzapine was superior for overall assessment.[13]

A 2013 review of first episode schizophrenia concluded that olanzapine is superior to haloperidol in providing a lower discontinuation rate, and in short-term symptom reduction, response rate, negative symptoms, depression, cognitive function, discontinuation due to poor efficacy, and long-term relapse, but not in positive symptoms or on the Clinical Global Impressions score. In contrast, pooled second generation antipsychotics showed superiority to first generation antipsychotics only against the discontinuation, negative symptoms (with a much larger effect seen among industry- compared to government-sponsored studies), and cognition scores. Olanzapine caused less extrapyramidal side effects, less akathisia, but caused significantly more weight gain, serum cholesterol increase, and triglyceride increase than haloperidol.[14] A 2012 review concluded that among 10 atypical antipsychotics, only clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone were better than first generation antipsychotics.[15] A 2011 review concluded that neither first- nor second generation antipsychotics produce clinically meaningful changes in Clinical Global Impression scores but found that olanzapine and amisulpride produce larger effects on the PANSS and BPRS batteries than 5 other second generation antipsychotics or pooled first generation antipsychotics.[16]

A 2014 meta analysis of 9 published trials having minimum duration 6 months and median duration 52 weeks concluded that olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone had better effects on cognitive function than amisulpride and haloperidol.[17]

Olanzapine is effective in treating the acute exacerbations of schizophrenia.[18][19]

Bipolar disorder

Olanzapine is recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence as a first line therapy for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder.[20] Other recommended first lines are haloperidol, quetiapine and risperidone.[20] It is recommended in combination with fluoxetine as a first line therapy for acute bipolar depression; and as a second line treatment by itself for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.[20]

The Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) recommends olanzapine as a first line maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder and the combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine as second line treatment for bipolar depression.[21]

A 2014 meta analysis concluded that olanzapine plus fluoxetine was the most effective among nine treatments for bipolar depression included in the analysis.[22]

Other

Evidence does not support the use of atypical antipsychotics including olanzapine in eating disorders.[23]

Olanzapine has not been rigorously evaluated in generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, delusional parasitosis or post-traumatic stress disorder. Olanzapine is no less effective than lithium or valproate, and more effective than placebo in treating bipolar disorder.[24] It has also been used for Tourette syndrome and stuttering.[25]

Elderly

Citing an increased risk of stroke, in 2004 the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM) in the UK issued a warning that olanzapine and risperidone, both atypical antipsychotic medications, should not be given to elderly patients with dementia. In the U.S., olanzapine comes with a black box warning for increased risk of death in elderly patients. It is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis.[26] However, a BBC investigation in June 2008 found that this advice was being widely ignored by British doctors.[27]

Adverse effects

The principal side effect of olanzapine is weight gain, which may be profound in some cases and/or associated with derangement in the blood lipid and blood sugar profiles (see section metabolic effects). A recent meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerance of 15 antipsychotic drugs (APDs) found that it had the highest propensity for causing weight gain out of the 15 APD compared with a SMD of 0.74[28] Extrapyramidal side effects, although potentially serious, are infrequent to rare from olanzapine[29] but may include tremors and muscle rigidity.

Several patient groups are at a heightened risk of side effects from olanzapine and antipsychotics in general. Olanzapine may produce non-trivial hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Likewise, the elderly are at a greater risk of falls and accidental injury. Young males appear to be at heightened risk of dystonic reactions, although these are relatively rare with olanzapine. Most antipsychotics, including olanzapine, may disrupt the body's natural thermoregulatory systems, thus permitting excursions to dangerous levels when situations (exposure to heat, strenuous exercise) occur.[4][30][31][32][5]

Paradoxical effects

While olanzapine is used therapeutically to treat serious mental illness, occasionally it can have the opposite effect and provoke serious paradoxical reactions in a small subgroup of people, with the drug causing unusual changes in personality, thoughts or behavior; hallucinations and excessive thoughts about suicide have also been linked to olanzapine use.[33]

Metabolic effects

Direct glucuronidation and cytochrome P450 mediated oxidation are the primary metabolic pathways for olanzapine. In vitro studies suggest that CYPs 1A2 and 2D6, and the flavin-containing monooxygenase system are involved in olanzapine oxidation. CYP2D6 mediated oxidation appears to be a minor metabolic pathway in vivo. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires all atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of developing hyperglycemia and diabetes, both of which are factors in the metabolic syndrome. These effects may be related to the drugs' ability to induce weight gain, although there are some reports of metabolic changes in the absence of weight gain,[34][35] Studies have indicated that olanzapine carries a greater risk of causing and exacerbating diabetes than another commonly prescribed atypical antipsychotic, Risperidone. Of all the atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine is one of the most likely to induce weight gain based on various measures.[36][37][38][39][40] The effect is dose dependent in humans[41] and animal models of olanzapine-induced metabolic side effects. There are some case reports of olanzapine-induced diabetic ketoacidosis.[42] Olanzapine may decrease insulin sensitivity,[43][44] though one 3-week study seems to refute this.[45] It may also increase triglyceride levels.[37]

Despite weight gain, a large multi-center randomized National Institute of Mental Health study found that olanzapine was better at controlling symptoms because patients were more likely to remain on olanzapine than the other drugs.[46] One small, open-label, non-randomized study suggests that taking olanzapine by orally dissolving tablets may induce less weight gain,[47] but this has not been substantiated in a blinded experimental setting.

Pregnancy and lactation

Olanzapine is associated with the highest placental exposure of any atypical antipsychotic.[48] Despite this the available evidence suggests it is safe during pregnancy, although the evidence is insufficiently strong to say anything with a high degree of confidence.[48] Olanzapine is associated with weight gain which according to recent studies may put olanzapine-treated patients' offspring at a heightened risk for neural tube defects (e.g. spina bifida).[49][50] Breastfeeding in women taking olanzapine is advised against due to the fact that olanzapine is secreted in breast milk with one study finding that the exposure to the infant (in mg per kg of body weight, that is) is about 1.8% that to the mother.[4]

Animal toxicology

Olanzapine has demonstrated carcinogenic effects in multiple studies when exposed chronically to female mice and rats, but not male mice and rats. The tumors found were in either the liver or mammary glands of the animals.[51]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing anti-psychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[52] Due to compensatory changes at dopamine, serotonin, adrenergic and histamine receptor sites in the central nervous system, withdrawal symptoms can occur during abrupt or over-rapid reduction in dosage. However, despite increasing demand for safe and effective antipsychotic withdrawal protocols or dose-reduction schedules, no specific guidelines with proven safety and efficacy are currently available. Support groups such as the Icarus Project, and other online forums provide resources and social support for those attempting to discontinue antipsychotics and other psychiatric medications.[53] Withdrawal symptoms reported to occur after discontinuation of antipsychotics include nausea, vomiting, lightheadedness, diaphoresis, dyskinesia, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, nervousness, dizziness, headache, excessive non-stop crying, and anxiety.[54][55] Some have argued additional somatic and psychiatric symptoms associated with dopaminergic hypersensitivity, including dyskinesia and acute psychosis, are common features of withdrawal in individuals treated with neuroleptics.[56][57][58][59] Thus, some suggest the withdrawal process itself may be schizo-mimetic, producing schizophrenia-like symptoms even in previously healthy patients.[60]

Overdose

Symptoms of an overdose include tachycardia, agitation, dysarthria, decreased consciousness and coma. Death has been reported after an acute overdose of 450 mg, but also survival after an acute overdose of 2000 mg.[61] There is no known specific antidote for olanzapine overdose, and even physicians are recommended to call a certified poison control center for information on the treatment of such a case.[61] Olanzapine is considered moderately toxic in overdose; more toxic than quetiapine, aripiprazole and the SSRIs and less toxic than the MAOIs and TCAs.[48]

Pharmacology

Olanzapine has a higher affinity for 5-HT2A serotonin receptors than D2 dopamine receptors, which is a common property of all atypical antipsychotics, aside from the benzamide antipsychotics such as amisulpride. Olanzapine also had the highest affinity of any second-generation antipsychotic towards the P-glycoprotein in one in vitro study.[62] P-glycoprotein transports a number of drugs across a number of different biological membranes including the blood-brain barrier, which could mean that less brain exposure to olanzapine results from this interaction with the P-glycoprotein.[63]

| Receptor | Ki (nM)[64] | Biologic action and notes[65] |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 2282 | Antagonist. |

| 5-HT1B | 585 | ? |

| 5-HT1D | 1061 | ? |

| 5-HT1E | 2209 | ? |

| 5-HT2A | 2.4 | Inverse agonist. May underlie the "atypicality" of the newer antipsychotics like olanzapine. May contribute to sedating effects. |

| 5-HT2B | 11.9 | Inverse agonist/antagonist. |

| 5-HT2C | 10.2 | Inverse agonist. May underlie the appetite-stimulating effects of olanzapine. |

| 5-HT3 | 202 | Antagonist. Possibly responsible, at least in part, for its antiemetic action. |

| 5-HT5A | 1212 | ? |

| 5-HT6 | 8.07 | Antagonist. |

| 5-HT7 | 105.2 | Antagonist. |

| α1A | 112 | Antagonist. Likely responsible for the orthostatic hypotension seen with its use.[65] |

| α1B | 263 | Antagonist. |

| α2A | 315 | Antagonist. |

| α2B | 81.8 | Antagonist |

| α2C | 28.9 | Antagonist. |

| M1 | 26 | Antagonist. Likely the chief receptor responsible for the anticholinergic effects seen with olanzapine's use.[65] |

| M2 | 63.5 | Antagonist. |

| M3 | 52.67 | Antagonist. Possible role in type 2 diabetes side-effects.[66] |

| M4 | 17.33 | Antagonist. |

| M5 | 7.5 | Antagonist. |

| D1 | 70.33 | Antagonist. |

| D2 | 3.00 | Antagonist. Likely responsible for the therapeutic effects of olanzapine against the positive symptoms of schizophrenia.[65] |

| D2Long | 31 | Antagonist. |

| D2Short | 28.77 | Antagonist. |

| D3 | 47 | Antagonist. |

| D4 | 14.33 | Antagonist. |

| D5 | 82 | Antagonist. |

| H1 | 2.19 | Inverse agonist. Likely responsible for the sedative effects of olanzapine.[65] |

| H2 | 44 | Antagonist. |

| H4 | >10000 | Antagonist. |

Olanzapine is a potent antagonist of the muscarinic M3 receptor,[67] which may underlie its diabetogenic side effects.[66][68] Additionally, olanzapine also exhibits a relatively low affinity for serotonin 5-HT1, GABAA, beta-adrenergic receptors, and benzodiazepine binding sites.[29][69]

The mode of action of olanzapine's antipsychotic activity is unknown. It may involve antagonism of dopamine and serotonin receptors. Antagonism of dopamine receptors is associated with extrapyramidal effects such as tardive dyskinesia(TD), and with therapeutic effects. Antagonism of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is associated with anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth and constipation, in addition it may suppress or reduce the emergence of extrapyramidal effects for the duration of treatment, however it offers no protection against the development of tardive dyskinesia. In common with other second generation (atypical) antipsychotics, olanzapine poses a relatively low risk of extrapyramidal side effects including TD, due to its high affinity for the D1 receptor over the D2 receptor.[70]

Antagonizing H1 histamine receptors causes sedation and may cause weight gain, although antagonistic actions at serotonin 5-HT2C and dopamine D2 receptors have also been associated with weight gain and appetite stimulation.[71]

Metabolism

Olanzapine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system; principally by isozyme 1A2 and to a lesser extent by 2D6. By these mechanisms more than 40% of the oral dose, on average, is removed by the hepatic first-pass effect.[29] Drugs or agents that increase the activity of CYP1A2, notably tobacco smoke, may significantly increase hepatic first-pass clearance of Olanzapine; conversely, drugs which inhibit 1A2 activity (examples: Ciprofloxacin, Fluvoxamine) may reduce Olanzapine clearance.[6]

Society and culture

Regulatory status

Olanzapine is approved in the U.S.A. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for:

- Treatment — in combination with fluoxetine — of depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder (December 2003).[72]

- Long-term treatment of bipolar I disorder (January 2004).[73][74]

- Treatment — in combination with fluoxetine — of resistant depression (March 2009).[75]

- Oral formulation: acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adults, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (monotherapy and in combination with lithium or sodium valproate)

- Intramuscular formulation: acute agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar I mania in adults

- Oral formulation combined with fluoxetine: treatment of acute depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults, or treatment of acute, resistant depression in adults [76]

- Treatment of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (September 1996[77]—March 2000).[78]

- Short-term treatment of acute manic episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (March 2000).[78]

- Short-term treatment of schizophrenia instead of the management of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (March 2000).[78]

- Maintaining treatment response in schizophrenic patients who had been stable for approximately eight weeks and were then followed for a period of up to eight months (November 2000).[78]

Controversy, prosecution, lawsuits and settlements

Eli Lilly has faced many lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa. In 2006, Lilly paid $700 million to settle 8,000 of these lawsuits.[79] In 2007, Eli Lilly agreed to pay up to $500 million to settle 18,000 more lawsuits.[citation needed]

In 2009, Eli Lilly pleaded guilty to a criminal misdemeanor charge of illegally marketing Zyprexa for off-label use and agreed to pay $1.4 billion.[80][81]

A New York Times article based on leaked company documents concluded that the company had engaged in a deliberate effort to downplay olanzapine's side effects.[82] The company denied these allegations and stated that the article had been based on cherry picked documents. Most of the documents were disclosed as the result of lawsuits by individuals who had taken the drug, though other documents had been stolen.[83] Eli Lilly filed a protection order to stop the dissemination of some of the documents which the judge believed to be confidential and "not generally appropriate for public consumption".[83] Temporary injunctions required those who had received the documents to return them and to remove them from websites.[84] Judge Jack B. Weinstein issued a permanent judgement against further dissemination of the documents and requiring their return by a number of parties named by Lilly.[83] On January 8, 2007, Judge Jack B. Weinstein refused the Electronic Frontier Foundation's motion to stay his order.[85] The documents given to The New York Times by Jim Gottstein show that senior Lilly executives may have kept important information from doctors about Zyprexa’s links to obesity and its tendency to raise blood sugar — both known risk factors for diabetes. The Times of London also reported that as early as 1998, Lilly considered the risk of drug-induced obesity to be a "top threat" to Zyprexa sales.[86] On October 9, 2000, senior Lilly research physician Robert Baker noted that an academic advisory board he belonged to was "quite impressed by the magnitude of weight gain on olanzapine and implications for glucose."[86]

Trade names

Olanzapine is generic and is available under many trade names worldwide.[1]

Dosage forms

Olanzapine is marketed in a number of countries, with tablets ranging from 2.5 to 20 milligrams. Zyprexa (and generic olanzapine) is available as an orally-disintegrating "wafer" which rapidly dissolves in saliva. It is also available in 10 milligram vials for intramuscular injection.[6]

Research

Olanzapine has been investigated for use as an antiemetic, particularly for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). A 2007 study demonstrated its successful potential for this use, achieving a complete response in the acute prevention of nausea and vomiting in 100% of patients treated with moderately and highly-emetogenic chemotherapy, when used in combination with palonosetron and dexamethasone.[87]

Olanzapine has been considered as part of an early psychosis approach for schizophrenia. The Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education (PRIME) study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Eli Lilly, tested the hypothesis that olanzapine might prevent the onset of psychosis in people at very high risk for schizophrenia. The study examined 60 patients with prodromal schizophrenia, who were at an estimated risk of 36–54% of developing schizophrenia within a year, and treated half with olanzapine and half with placebo.[88] In this study, patients receiving olanzapine did not have a significantly lower risk of progressing to psychosis. Olanzapine was effective for treating the prodromal symptoms, but was associated with significant weight gain.[89]

References

- ^ a b Drugs.com Drugs.com international listings for Olanzapine Page accessed August 4, 2015

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Burton, Michael E.; Shaw, Leslie M.; Schentag, Jerome J.; Evans, William E. (May 1, 2005). Applied Pharmacokinetics & Pharmacodynamics: Principles of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 815. ISBN 978-0-7817-4431-7.

- ^ a b c d e "PRODUCT INFORMATION OLANZAPINE SANDOZ® 2.5mg/5mg/7.5mg/10mg/15mg/20mg FILM-COATED TABLETS" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sandoz Pty Ltd. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Zyprexa, Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Olanzapine Prescribing Information" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "Lilly 2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Lilly. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (25 March 2009). "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ Duggan L, Fenton M, Dardennes RM, El-Dosoky A, Indran S (2005). Duggan, Lorna (ed.). "Olanzapine for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001359. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001359.pub2. PMID 10796640.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- ^ Barnes TR (2011). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 25 (5): 567–620. doi:10.1177/0269881110391123. PMID 21292923.

- ^ Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ (2013). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects". World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 14 (1): 2–44. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.739708. PMID 23216388.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abou-Setta, AM; Mousavi, SS; Spooner, C; Schouten, JR; Pasichnyk, D; Armijo-Olivo, S; Beaith, A; Seida, JC; Dursun, S; Newton, AS; Hartling, L (August 2012). PMID 23035275.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Zhang JP, Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Malhotra AK, Kane JM, Correll CU (July 2013). "Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (6): 1205–18. doi:10.1017/S1461145712001277. PMC 3594563. PMID 23199972.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Citrome L (August 2012). "A systematic review of meta-analyses of the efficacy of oral atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 13 (11): 1545–73. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.626769. PMID 21999805.

- ^ Lepping P, Sambhi RS, Whittington R, Lane S, Poole R (May 2011). "Clinical relevance of findings in trials of antipsychotics: systematic review". Br J Psychiatry. 198 (5): 341–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075366. PMID 21525517.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Désaméricq G, Schurhoff F, Meary A, et al. (February 2014). "Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70 (2): 127–34. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1600-y. PMID 24145817.

- ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- ^ Osser DN, Roudsari MJ, Manschreck T (2013). "The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on schizophrenia". Harv Rev Psychiatry. 21 (1): 18–40. doi:10.1097/HRP.0b013e31827fd915. PMID 23656760.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c [+http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/chapter/1-recommendations "Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care | 1-recommendations | Guidance and guidelines | NICE"].

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O'Donovan C, et al. (December 2006). "Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007". Bipolar Disord. 8 (6): 721–39. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00432.x. PMID 17156158.

- ^ Selle V, Schalkwijk S, Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ (March 2014). "Treatments for acute bipolar depression: meta-analyses of placebo-controlled, monotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, lithium and antipsychotics". Pharmacopsychiatry. 47 (2): 43–52. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1363258. PMID 24549862.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maglione M, Maher AR, Hu J, et al. (2011). "Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update". PMID 22132426.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Review of olanzapine in the management of bipolar disorders". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 3 (5): 579–587. October 2007. PMC 2656294. PMID 19300587.

- ^ Scott, Lisa (Winter 2006). "Genetic and Neurological Factors in Stuttering". Stuttering Foundation of America.

- ^ "Important Safety Information for Olanzapine". Zyprexa package insert. Eli Lilly & Company. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. [...] ZYPREXA (olanzapine) is not approved for the treatment of elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.

- ^ "Doctors 'ignoring drugs warning'". BBC News. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Örey D, Richter F, et al. (2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- ^ a b c Lexi-Comp Inc. (2010) Lexi-Comp Drug Information Handbook 19th North American Ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp Inc. ISBN 978-1-59195-278-7.

- ^ Stöllberger C., Lutz W., Finsterer J. (2009). "Heat-related side-effects of neurological and non-neurological medication may increase heatwave fatalities". European Journal of Neurology. 16: 879–882. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02581.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "OLANZAPINE (olanzapine) tablet OLANZAPINE (olanzapine) tablet, orally disintegrating [Prasco Laboratories]". DailyMed. Prasco Laboratories. September 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Olanzapine 10 mg tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Aurobindo Pharma - Milpharm Ltd. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ Cerner Multum Incorporated (27 September 2011). "Olanzapine". Drugs.com.

- ^ Ramankutty G (2002). "Olanzapine-induced destabilization of diabetes in the absence of weight gain". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 105 (3): 235–6, discussion 236–7. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.2c257a.x. PMID 11939979.

- ^ Lambert MT, Copeland LA, Sampson N, Duffy SA (2006). "New-onset type-2 diabetes associated with atypical antipsychotic medications". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 30 (5): 919–23. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.02.007. PMID 16581171.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moyer, Paula (Oct 25, 2005). "CAFE Study Shows Varying Benefits Among Atypical Antipsychotics". Medscape Medical News. WebMD. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ a b AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (4 April 2006). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Olanzapine, Quetiapine and Risperidone in the Treatment of First Episode Psychosis: A Randomised Double Blind 52 Week Comparison". AstraZeneca Clinical Trials. AstraZeneca PLC. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

At week 12, the olanzapine-treated group had more weight gain, a higher increase in [ body mass index ], and a higher proportion of patients with a BMI increase of at least 1 unit compared with the quetiapine and risperidone groups (p<=0.01).

- ^ Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA, Goldstein D, Pashdag J, Mintz J, Marder SR (1999). "Novel Antipsychotics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (6): 358–63. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0602. PMID 10401912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "NIMH study to guide treatment choices for schizophrenia" (Press release). National Institute of Mental Health. 19 September 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- ^ McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, Hamer RM, Gu H, Lazarus A, Sweitzer D, Olexy C, Weiden P, Strakowski SD (2007). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Olanzapine, Quetiapine, and Risperidone in the Treatment of Early Psychosis: A Randomized, Double-Blind 52-Week Comparison". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (7): 1050–60. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1050. PMID 17606657.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nemeroff CB (1997). "Dosing the antipsychotic medication olanzapine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (Suppl 10): 45–9. PMID 9265916.

- ^ Fulbright, A. R.; Breedlove, K. T. (2006). "Complete Resolution of Olanzapine-Induced Diabetic Ketoacidosis". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 19 (4): 255–8. doi:10.1177/0897190006294180.

- ^ Chiu CC, Chen CH, Chen BY, Yu SH, Lu ML (2010). "The time-dependent change of insulin secretion in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 34 (6): 866–70. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.003. PMID 20394794.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sacher J, Mossaheb N, Spindelegger C, Klein N, Geiss-Granadia T, Sauermann R, Lackner E, Joukhadar C, Müller M, Kasper S (2007). "Effects of Olanzapine and Ziprasidone on Glucose Tolerance in Healthy Volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1633–41. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301541. PMID 17712347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sowell M, Mukhopadhyay N, Cavazzoni P, Carlson C, Mudaliar S, Chinnapongse S, Ray A, Davis T, Breier A, Henry RR, Dananberg J (2003). "Evaluation of Insulin Sensitivity in Healthy Volunteers Treated with Olanzapine, Risperidone, or Placebo: A Prospective, Randomized Study Using the Two-Step Hyperinsulinemic, Euglycemic Clamp". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 88 (12): 5875–80. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021884. PMID 14671184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carey, Benedict (September 20, 2005). "Little Difference Found in Schizophrenia Drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ de Haan L, van Amelsvoort T, Rosien K, Linszen D (2004). "Weight loss after switching from conventional olanzapine tablets to orally disintegrating olanzapine tablets". Psychopharmacology. 175 (3): 389–90. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1951-2. PMID 15322727.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Taylor, D. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Rasmussen SA, Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J (June 2008). "Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a metaanalysis". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 198 (6): 611–619. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.021. PMID 18538144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McMahon DM, Liu J, Zhang H, Torres ME, Best RG (February 2013). "Maternal obesity, folate intake, and neural tube defects in offspring". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 97 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1002/bdra.23113. PMID 23404872.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brambilla G, Mattioli F, Martelli A (2009). "Genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of antipsychotics and antidepressants". Toxicology. 261 (3): 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2009.04.056. PMID 19410629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "4.2.1 Antipsychotic drugs". British National Formulary (57th ed.). London and Chicago: Pharmaceutical Press. March 2009. pp. 221–31. ISBN 978-0-85711-065-7.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ^ "Harm Reduction Guide To Coming Off Psychiatric Drugs & Withdrawal". Icarus Project. April 23, 2008.

- ^ Kim DR, Staab JP (2005). "Quetiapine Discontinuation Syndrome". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (5): 1020. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1020. PMID 15863814.

- ^ Michaelides C, Thakore-James M, Durso R (2005). "Reversible withdrawal dyskinesia associated with quetiapine". Movement Disorders. 20 (6): 769–70. doi:10.1002/mds.20427. PMID 15747370.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chouinard G, Jones BD (1980). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis: Clinical and pharmacologic characteristics". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (1): 16–21. PMID 6101522.

- ^ Miller R, Chouinard G (1993). "Loss of striatal cholinergic neurons as a basis for tardive and L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis and refractory schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 34 (10): 713–38. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(93)90044-E. PMID 7904833.

- ^ Chouinard G, Jones BD, Annable L (1978). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 135 (11): 1409–10. PMID 30291.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seeman P, Weinshenker D, Quirion R, Srivastava LK, Bhardwaj SK, Grandy DK, Premont RT, Sotnikova TD, Boksa P, El-Ghundi M, O'dowd BF, George SR, Perreault ML, Männistö PT, Robinson S, Palmiter RD, Tallerico T (2005). "Dopamine supersensitivity correlates with D2High states, implying many paths to psychosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (9): 3513–8. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.3513S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409766102. JSTOR 3374957. PMC 548961. PMID 15716360.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moncrieff J (2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- ^ a b "Symbyax (Olanzapine and fluoxetine) drug overdose and contraindication information". RxList: The Internet Drug Index. WebMD. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ Wang JS, Zhu HJ, Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL (September 2006). "Evaluation of antipsychotic drugs as inhibitors of multidrug resistance transporter P-glycoprotein". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 187 (4): 415–423. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0437-9. PMID 16810505.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moons T, de Roo M, Claes S, Dom G (August 2011). "Relationship between P-glycoprotein and second-generation antipsychotics". Pharmacogenomics. 12 (8): 1193–1211. doi:10.2217/pgs.11.55. PMID 21843066.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Deng C (10 October 2013). "Second Generation Antipsychotic-Induced Type 2 Diabetes: A Role for the Muscarinic M3 Receptor". CNS Drugs. 27: 1069–1080. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0115-5. PMID 24114586. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson DE, Yamazaki H, Ward KM, Schmidt AW, Lebel WS, Treadway JL, Gibbs EM, Zawalich WS, Rollema H (2005). "Inhibitory Effects of Antipsychotics on Carbachol-Enhanced Insulin Secretion from Perifused Rat Islets: Role of Muscarinic Antagonism in Antipsychotic-Induced Diabetes and Hyperglycemia". Diabetes. 54 (5): 1552–8. doi:10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1552. PMID 15855345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silvestre JS, Prous J (2005). "Research on adverse drug events. I. Muscarinic M3 receptor binding affinity could predict the risk of antipsychotics to induce type 2 diabetes". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (5): 289–304. doi:10.1358/mf.2005.27.5.908643. PMID 16082416.

- ^ "olanzapine". NCI Drug Dictionary. National Cancer Institute.

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA (2009) Foye's Medicinal Chemistry, 6th edition. Wolters Kluwer: New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-89960-30-8.

- ^ "Medication and Weight Control"

- ^ "NDA 21-520" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2003-12-24. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "NDA 20-592 / S-019" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 2004-01-14. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ Pillarella J, Higashi A, Alexander GC, Conti R (2012). "Trends in the use of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder in the United States, 1998-2009". Psychiatric Services. 63 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100092. PMID 22227765.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Forbes.com[dead link]

- ^ treatment resistant depression defined as major depressive disorder in adult patients who do not respond to two separate trials of different antidepressants of adequate dose and duration in the current episode

- ^ "NDA 20-592" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 1996-09-06. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ a b c d "Eli Lilly and Company Agrees to Pay $1.415 Billion to Resolve Allegations of Off-label Promotion of Zyprexa". U.S. Justice Department. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ^ Berenson, Alex (January 4, 2007). "Mother Wonders if Psychosis Drug Helped Kill Son". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ MSN.com Lilly settles Zyprexa suit for $1.42 billion.

- ^ Berenson, Alex (December 18, 2006). "Drug Files Show Maker Promoted Unapproved Use". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Berenson, Alex (December 17, 2006). "Eli Lilly Said to Play Down Risk of Top Pill". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c L-Z\In re Zyprexa\Documents Leak\Injunction Memo & Order\FINAL INJUNCTION MEMO 2.13.07.wpd

- ^ EFF.org

- ^ Press Releases: January, 2007 | Electronic Frontier Foundation

- ^ a b Eli Lilly was Concerned by Zyprexa Side-Effects from 1998,[dead link] The Times (London), January 23, 2007

- ^ Navari RM, Einhorn LH, Loehrer PJ, Passik SD, Vinson J, McClean J, Chowhan N, Hanna NH, Johnson CS (2007). "A phase II trial of olanzapine, dexamethasone, and palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A Hoosier oncology group study". Supportive Care in Cancer. 15 (11): 1285–91. doi:10.1007/s00520-007-0248-5. PMID 17375339.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller TJ, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman R, Lindborg S, Tohen M, Breier A (2003). "The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis". Schizophrenia Research. 61 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00439-5. PMID 12648731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller T, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman RE, Preda A, Epstein I, Addington D, Lindborg S, Trzaskoma Q, Tohen M, Breier A (2006). "Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Olanzapine Versus Placebo in Patients Prodromally Symptomatic for Psychosis". American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (5): 790–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.790. PMID 16648318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Zyprexa.com - official Zyprexa brand website from Eli Lilly and Company

- Zyprexa package insert

- Berenson, Alex (December 17, 2006). "Lilly Settles With 18,000 Over Zyprexa". New York Times.