Sevoflurane

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: the content/scope are not encyclopedic for an important anesthetic, and sources are often primary/lacking. (August 2014) |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sojourn, Ultane, Sevorane |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Routes of administration | inhaled |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.171.146 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

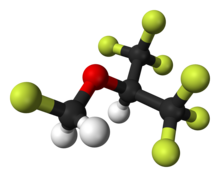

| Formula | C4H3F7O |

| Molar mass | 200.055 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Sevoflurane (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-(fluoromethoxy)propane; synonym, fluoromethyl hexafluoroisopropyl ether), is a sweet-smelling, nonflammable, highly fluorinated methyl isopropyl ether used as an inhalational anaesthetic for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. After desflurane, it is the volatile anesthetic with the fastest onset and offset.[1]

It is one of the most commonly used volatile anesthetic agents, particularly for outpatient anesthesia,[2] across all ages, as well as in veterinary medicine. Together with desflurane, sevoflurane is replacing isoflurane and halothane in modern anesthesiology. It is often administered in a mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen.

Sevoflurane "has an excellent safety record",[2] but is under review for potential neurotoxicity, especially relevant to administration in infants and children, and rare reports similar to halothane hepatotoxicity.[2] Sevoflurane is the preferred agent for mask induction due to its lesser irritation to mucous membranes.

Sevoflurane was discovered by Ross Terrell[3] and independently by Bernard M Regan. A detailed report of its development and properties appeared in 1975 in a paper authored by Richard Wallin, Bernard Regan, Martha Napoli and Ivan Stern. It was introduced into clinical practice initially in Japan in 1990. The rights for sevoflurane worldwide were held by AbbVie. It is now available as a generic drug.

Medical uses

Sevoflurane is an inhaled anaesthetic that is often used to put children asleep for surgery.[4] During the process of waking up from the medication, it has been known to cause agitation and delirium.[4] It is not clear if this can be prevented.[4]

Adverse effects

Sevoflurane raises intracranial pressure and can cause respiratory depression.[5]

Studies examining a current significant health concern, anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (including with sevoflurane, and especially with children and infants) are "fraught with confounders, and many are underpowered statistically", and so are argued to need "further data... to either support or refute the potential connection".[6]

Concern regarding the safety of anaesthesia is especially acute with regard to children and infants, where preclinical evidence from relevant animal models suggest that common clinically important agents, including sevoflurane, may be neurotoxic to the developing brain, and so cause neurobehavioural abnormalities in the long term; two large-scale clinical studies (PANDA and GAS) were ongoing as of 2010, in hope of supplying "significant [further] information" on neurodevelopmental effects of general anaesthesia in infants and young children, including where sevoflurane is used.[7]

Pharmacology

The exact mechanism of the action of general anaesthetics have not been delineated.[8] Sevoflurane is thought to potentially act as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.[9] However, it also acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist,[10] potentiates glycine receptor currents,[9] and inhibits nACh[11] and 5-HT3 receptor currents.[12][13][14]

Physical properties

| Boiling point: | 58.6 °C | (at 101.325 kPa) | |

| Density: | 1.517–1.522 g/cm³ | (at 20 °C) | |

| MAC : | 2.1 vol % | ||

| Molecular weight: | 200 u | ||

| Vapor pressure: | 157 mmHg (20.9 kPa) | (at 20 °C) | |

| 197 mmHg (26.3 kPa) | (at 25 °C) | ||

| 317 mmHg (42.3 kPa) | (at 36 °C) | ||

| Blood:Gas partition coefficient: | 0.68 | ||

| Oil:Gas partition coefficient: | 47 |

References

- ^ Sakai EM; Connolly LA; Klauck JA (December 2005). "Inhalation anesthesiology and volatile liquid anesthetics: focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane". Pharmacotherapy. 25 (12): 1773–88. doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.12.1773. PMID 16305297.

- ^ a b c Livertox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury (2014) "Drug Record: Sevoflurane", U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2 July 2014 update, see [1], accessed 15 August 2014.

- ^ Burns, William; Edmond I Eger II (August 2011). "Ross C. Terrell, PhD, an Anesthetic Pioneer". Anesth. Analg. 2. 113 (113): 387–9. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3182222b8a.

- ^ a b c Costi, D; Cyna, AM; Ahmed, S; Stephens, K; Strickland, P; Ellwood, J; Larsson, JN; Chooi, C; Burgoyne, LL; Middleton, P (Sep 12, 2014). "Effects of sevoflurane versus other general anaesthesia on emergence agitation in children". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD007084. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007084.pub2. PMID 25212274.

- ^ "Sevoflurane".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vlisides, P; Xie, Z. (2012). "Neurotoxicity of general anesthetics: an update". Curr Pharm Design. 18 (38): 6232–40. doi:10.2174/138161212803832344. PMID 22762477.

- ^ Sun, L. (2010). "Early childhood general anaesthesia exposure and neurocognitive development". Br J Anaesth. 105 (Suppl 1): i61–8. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq302. PMID 21148656.

- ^ "How does anesthesia work?". Scientific American. 7 February 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ a b Jürgen Schüttler; Helmut Schwilden (8 January 2008). Modern Anesthetics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9.

- ^ Brosnan, Robert J; Thiesen, Roberto (2012). "Increased NMDA receptor inhibition at an increased Sevoflurane MAC". BMC Anesthesiology. 12 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-12-9. ISSN 1471-2253.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Christa J. Van Dort (2008). Regulation of Arousal by Adenosine A(1) and A(2A) Receptors in the Prefrontal Cortex of C57BL/6J Mouse. ProQuest. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-549-99431-2.

- ^ Jürgen Schüttler; Helmut Schwilden (8 January 2008). Modern Anesthetics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9.

- ^ Suzuki T; Koyama H; Sugimoto M; Uchida I; Mashimo T (March 2002). "The diverse actions of volatile and gaseous anesthetics on human-cloned 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesiology. 96 (3): 699–704. doi:10.1097/00000542-200203000-00028. PMID 11873047.

- ^ Hang LH; Shao DH; Wang H; Yang JP (2010). "Involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors in sevoflurane-induced hypnotic and analgesic effects in mice" (PDF). Pharmacol Rep. 62 (4): 621–6. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70319-4. PMID 20885002.

Further reading

- Patel SS; Goa KL (April 1996). "Sevoflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its clinical use in general anaesthesia". Drugs. 51 (4): 658–700. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651040-00009. PMID 8706599.

"Erratum". Drugs. 52 (2): 253. August 1996. doi:10.1007/bf03257493. - Wallin, Richard F., Regan, Bernard M., Napoli, Martha D., Stern, Ivan j. (Nov–Dec 1975). "Sevoflurane: A New Inhalational Anesthetic Agent". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 54 (6): 758–766. doi:10.1213/00000539-197511000-00021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)