Donald Trump: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 953873757 by EditQwerty (talk) - we want this to establish the date of the picture and the fact that it is the official portrait. Also, we often get requests to change it, so having a caption probably eliminates some of those requests. |

EditQwerty (talk | contribs) In 2017, this how you describe an image. |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| image = Donald Trump official portrait.jpg<!-- DO NOT CHANGE the picture without prior consensus, see [[Talk:Donald Trump#Current consensus]], item 1. --> |

| image = Donald Trump official portrait.jpg<!-- DO NOT CHANGE the picture without prior consensus, see [[Talk:Donald Trump#Current consensus]], item 1. --> |

||

| alt = Head shot of Trump smiling in front of the U.S. flag. He is wearing a dark blue suit jacket, white shirt, light blue necktie, and American flag lapel pin. |

| alt = Head shot of Trump smiling in front of the U.S. flag. He is wearing a dark blue suit jacket, white shirt, light blue necktie, and American flag lapel pin. |

||

| caption = |

| caption = Trump in 2017 |

||

| order = 45th<!-- DO NOT ADD A LINK. Please discuss any proposal on the talk page first. Most recent discussion at [[Talk:Donald Trump/Archive 65#Link-ifying "45th" in the Infobox?]] had a weak consensus to keep the status-quo of no link. --> |

| order = 45th<!-- DO NOT ADD A LINK. Please discuss any proposal on the talk page first. Most recent discussion at [[Talk:Donald Trump/Archive 65#Link-ifying "45th" in the Infobox?]] had a weak consensus to keep the status-quo of no link. --> |

||

| office = President of the United States |

| office = President of the United States |

||

Revision as of 15:01, 29 April 2020

Donald Trump | |

|---|---|

Trump in 2017 | |

| 45th President of the United States | |

| Assumed office January 20, 2017 | |

| Vice President | Mike Pence |

| Preceded by | Barack Obama |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Donald John Trump June 14, 1946 Queens, New York City |

| Political party | Republican (1987–1999, 2009–2011, 2012–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Parent(s) | Fred Trump Mary Anne MacLeod |

| Relatives | Family of Donald Trump |

| Residences |

|

| Alma mater | The Wharton School (BS in Econ.) |

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

| Nickname | "The Donald"[1] |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Business and personal 45th President of the United States Tenure

Impeachments Civil and criminal prosecutions Interactions involving Russia  |

||

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is the 45th and current president of the United States. Before entering politics, he was a businessman and television personality.

Trump was born and raised in Queens, a borough of New York City, and received a bachelor's degree in economics from the Wharton School. He took charge of his family's real-estate business in 1971, renamed it The Trump Organization, and expanded its operations from Queens and Brooklyn into Manhattan. The company built or renovated skyscrapers, hotels, casinos, and golf courses. Trump later started various side ventures, mostly by licensing his name. He produced and hosted The Apprentice, a reality television series, from 2003 to 2015. As of 2020[update], Forbes estimated his net worth to be $2.1 billion.[a]

Trump entered the 2016 presidential race as a Republican and defeated 16 other candidates in the primaries. His political positions have been described as populist, protectionist, and nationalist. Despite not being favored in most forecasts, he was elected over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, although he lost the popular vote. He became the oldest first-term U.S. president,[b] and the first without prior military or government service. His election and policies have sparked numerous protests. Trump has made many false or misleading statements during his campaign and presidency. The statements have been documented by fact-checkers, and the media have widely described the phenomenon as unprecedented in American politics. Many of his comments and actions have been characterized as racially charged or racist.

During his presidency, Trump ordered a travel ban on citizens from several Muslim-majority countries, citing security concerns; after legal challenges, the Supreme Court upheld the policy's third revision. He enacted a tax-cut package for individuals and businesses, rescinding the individual health insurance mandate. He appointed Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. In foreign policy, Trump has pursued an America First agenda, withdrawing the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations, the Paris Agreement on climate change, and the Iran nuclear deal. During increased tensions with Iran, he ordered the killing of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. He imposed import tariffs triggering a trade war with China, recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and withdrew U.S. troops from northern Syria to avoid Turkey's offensive on American-allied Kurds.

A special counsel investigation led by Robert Mueller found that Trump and his campaign welcomed and encouraged Russian foreign interference in the 2016 presidential election under the belief that it would be politically advantageous, but did not find sufficient evidence to press charges of criminal conspiracy or coordination with Russia. Mueller also investigated Trump for obstruction of justice, and his report neither indicted nor exonerated Trump on that count. A 2019 House of Representatives impeachment inquiry found that Trump solicited foreign interference in the 2020 U.S. presidential election from Ukraine to help his re-election bid and then obstructed the inquiry itself. The House impeached Trump on December 18, 2019, for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. The Senate acquitted him of both charges on February 5, 2020.

Personal life

Early life and education

Donald John Trump was born on June 14, 1946, at the Jamaica Hospital in the borough of Queens, New York City.[2] His father was Frederick Christ Trump, a Bronx-born real estate developer whose parents were German immigrants. His mother was Scottish-born housewife Mary Anne MacLeod Trump. Trump grew up in the Jamaica Estates neighborhood of Queens and attended the Kew-Forest School from kindergarten through seventh grade.[3][4] At age 13, he was enrolled in the New York Military Academy, a private boarding school.[5] In 1964, Trump enrolled at Fordham University. Two years later he transferred to the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.[6] While at Wharton, he worked at the family business, Elizabeth Trump & Son.[7] He graduated in May 1968 with a B.S. in economics.[6][8] Profiles of Trump published in The New York Times in 1973 and 1976 erroneously reported that he had graduated first in his class at Wharton, but he had never made the school's honor roll.[9] In 2015, Trump's lawyer Michael Cohen threatened Fordham University and the New York Military Academy with legal action if they released Trump's academic records.[10]

While in college, Trump obtained four student draft deferments.[11] In 1966, he was deemed fit for military service based upon a medical examination, and in July 1968 a local draft board classified him as eligible to serve.[12] In October 1968, he was medically deferred and classified 1-Y (unqualified for duty except in the case of a national emergency).[13] In 1972, he was reclassified 4-F due to bone spurs, which permanently disqualified him from service.[14][15] Trump said in 2015 that the medical deferment was due to a bone spur in a foot, though he could not remember which foot had been afflicted.[13]

Family

Trump's father, Fred, was born in 1905 in the Bronx. He started working with his mother in real estate when he was 15. Their company, "E. Trump & Son", founded in 1923,[16] was active in the New York boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn, building and selling thousands of houses, barracks, and apartments.[17] In spite of his German ancestry, Fred claimed to be Swedish amid the anti-German sentiment sparked by World War II; Trump repeated this claim until the 1990s.[18] Trump's mother Mary Anne MacLeod was born in Scotland.[19] Fred and Mary were married in 1936 and raised their family in Queens.[20] Trump grew up with three elder siblings – Maryanne, Fred Jr., and Elizabeth – and younger brother Robert.[21]

In 1977, Trump married Czech model Ivana Zelníčková.[22] They have three children, Donald Jr. (born 1977), Ivanka (born 1981), and Eric (born 1984), and ten grandchildren.[23] Ivana became a naturalized United States citizen in 1988.[24] The couple divorced in 1992, following Trump's affair with actress Marla Maples.[25] Maples and Trump married in 1993[26] and had one daughter, Tiffany (born 1993).[27] They were divorced in 1999,[28] and Tiffany was raised by Marla in California.[29] In 2005, Trump married Slovenian model Melania Knauss.[30] They have one son, Barron (born 2006).[31] Melania gained U.S. citizenship in 2006.[32]

Religion

Trump is a Presbyterian and as a child was confirmed at the First Presbyterian Church in Jamaica, Queens.[33] In the 1970s, his parents joined the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan.[34] The pastor at Marble, Norman Vincent Peale,[33] ministered to Trump's family and mentored him until Peale's death in 1993.[35][34]

While campaigning, Trump referred to The Art of the Deal as his second favorite book; he said, "Nothing beats the Bible."[36] In November 2019, Trump appointed his personal pastor, controversial televangelist Paula White, to the White House Office of Public Liaison.[37]

Health and lifestyle

Trump abstains from alcohol, a reaction to his older brother Fred Trump Jr.'s alcoholism and early death.[38] He says he has never smoked cigarettes or cannabis.[39] He likes fast food.[40] He has said he prefers three to four hours of sleep per night.[41] He has called golfing his "primary form of exercise",[42] although he usually does not walk the course.[43] He considers exercise a waste of energy.[44][45]

In December 2015, Harold Bornstein, who had been Trump's personal physician since 1980, wrote in a letter that he would "be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency".[46] In May 2018, Bornstein said Trump himself had dictated the contents of the letter,[47] and that three Trump agents had removed his medical records in February 2017 without due authorization.[48]

In January 2018, White House physician Ronny Jackson said Trump was in excellent health and that his cardiac assessment revealed no issues.[49] Several outside cardiologists commented that Trump's 2018 LDL cholesterol level of 143 did not indicate excellent health.[50] In February 2019, after a new examination, White House physician Sean Conley said Trump was in "very good health overall", although he was clinically obese.[51] His 2019 coronary CT calcium scan score indicates he suffers from a form of coronary artery disease common for white men of his age.[52]

Wealth

In 1982, Trump was listed on the initial Forbes list of wealthy individuals as having a share of his family's estimated $200 million net worth. His financial losses in the 1980s caused him to be dropped from the list between 1990 and 1995.[53] In its 2020 billionaires ranking, Forbes estimated Trump's net worth at $2.1 billion[a] (1,001st in the world, 275th in the U.S.)[56] making him one of the richest politicians in American history and the first billionaire American president.[56] During the three years since Trump announced his presidential run in 2015, Forbes estimated his net worth declined 31% and his ranking fell 138 spots.[57] When he filed mandatory financial disclosure forms with the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) in July 2015, Trump claimed a net worth of about $10 billion;[58] however FEC figures cannot corroborate this estimate because they only show each of his largest buildings as being worth over $50 million, yielding total assets worth more than $1.4 billion and debt over $265 million.[59] Trump said in a 2007 deposition, "My net worth fluctuates, and it goes up and down with markets and with attitudes and with feelings, even my own feelings."[60]

Journalist Jonathan Greenberg reported in April 2018 that Trump, using a pseudonym "John Barron", called him in 1984 to falsely assert that he owned "in excess of ninety percent" of the Trump family's business, in an effort to secure a higher ranking on the Forbes 400 list of wealthy Americans. Greenberg also wrote that Forbes had vastly overestimated Trump's wealth and wrongly included him on the Forbes 400 rankings of 1982, 1983, and 1984.[61]

Trump has often said he began his career with "a small loan of one million dollars" from his father, and that he had to pay it back with interest.[62] In October 2018, The New York Times reported that Trump "was a millionaire by age 8", borrowed at least $60 million from his father, largely failed to reimburse him, and had received $413 million (adjusted for inflation) from his father's business empire over his lifetime.[63][64] According to the report, Trump and his family committed tax fraud, which a lawyer for Trump denied. The tax department of New York says it is "vigorously pursuing all appropriate avenues of investigation" into it.[65][66] Analyses by The Economist and The Washington Post have concluded that Trump's investments underperformed the stock market.[67][68] Forbes estimated in October 2018 that the value of Trump's personal brand licensing business had declined by 88% since 2015, to $3 million.[69]

Trump's tax returns from 1985 to 1994 show net losses totaling $1.17 billion over the ten-year period, in contrast to his claims about his financial health and business abilities. The New York Times reported that "year after year, Mr. Trump appears to have lost more money than nearly any other individual American taxpayer", and Trump's "core business losses in 1990 and 1991 – more than $250 million each year – were more than double those of the nearest taxpayers in the I.R.S. information for those years". In 1995 his reported losses were $915.7 million.[70][71]

Business career

Real estate

Trump began his career in 1968 at his father Fred's real estate development company, E. Trump & Son, which owned middle-class rental housing in New York City's outer boroughs.[72][73] In 1971, he was named president of the family company and renamed it The Trump Organization.[74]

Manhattan developments

Trump attracted public attention in 1978 with the launch of his family's first Manhattan venture, the renovation of the derelict Commodore Hotel, adjacent to Grand Central Terminal. The financing was facilitated by a $400 million city property tax abatement arranged by Fred Trump,[75] who also joined Hyatt in guaranteeing $70 million in bank construction financing.[76][77] The hotel reopened in 1980 as the Grand Hyatt Hotel,[78] and that same year, Trump obtained rights to develop Trump Tower, a mixed-use skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan.[79] The building houses the headquarters of the Trump Organization and was Trump's primary residence until 2019.[80][81]

In 1988, Trump acquired the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan with a loan of $425 million from a consortium of banks. Two years later, the hotel filed for bankruptcy protection, and a reorganization plan was approved in 1992.[82] In 1995, Trump lost the hotel to Citibank and investors from Singapore and Saudi Arabia, who assumed $300 million of the debt.[83][84]

In 1996, Trump acquired a vacant 71-story skyscraper at 40 Wall Street. After an extensive renovation, the high-rise was renamed the Trump Building.[85] In the early 1990s, Trump won the right to develop a 70-acre (28 ha) tract in the Lincoln Square neighborhood near the Hudson River. Struggling with debt from other ventures in 1994, Trump sold most of his interest in the project to Asian investors who were able to finance completion of the project, Riverside South. Trump temporarily retained a partial stake in an adjacent site along with other investors.[86]

Palm Beach estate

In 1985, Trump acquired the Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida.[87] Trump used a wing of the estate as a home, while converting the remainder into a private club with an initiation fee and annual dues.[88] The initiation fee was $100,000 until 2016; it was doubled to $200,000 in January 2017.[89] On September 27, 2019, Trump declared Mar-a-Lago his primary residence.[81]

Atlantic City casinos

In 1984, Trump opened Harrah's at Trump Plaza hotel and casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey with financing from the Holiday Corporation, who also managed the operation. Gambling had been legalized there in 1977 in an effort to revitalize the once-popular seaside destination.[90] Soon after it opened the casino was renamed "Trump Plaza", but the property's poor financial results worsened tensions between Holiday and Trump, who paid Holiday $70 million in May 1986 to take sole control of the property.[91] Earlier, Trump had also acquired a partially completed building in Atlantic City from the Hilton Corporation for $320 million. Upon its completion in 1985, that hotel and casino was called Trump Castle. Trump's then-wife Ivana managed it until 1988.[92][93]

Trump acquired a third casino in Atlantic City, the Taj Mahal, in 1988 in a highly leveraged transaction.[94] It was financed with $675 million in junk bonds and completed at a cost of $1.1 billion, opening in April 1990.[95][96][97] The project went bankrupt the following year,[96] and the reorganization left Trump with only half his initial ownership stake and required him to pledge personal guarantees of future performance.[98] Facing "enormous debt", he gave up control of his money-losing airline, Trump Shuttle, and sold his 282-foot (86 m) mega yacht, the Trump Princess, which had been indefinitely docked in Atlantic City while leased to his casinos for use by wealthy gamblers.[99][100]

In 1995, Trump founded Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts (THCR), which assumed ownership of Trump Plaza, Trump Castle, and the Trump Casino in Gary, Indiana.[101] THCR purchased the Taj Mahal in 1996 and underwent successive bankruptcies in 2004, 2009, and 2014, leaving Trump with only ten percent ownership.[102] He remained chairman of THCR until 2009.[103]

Golf courses

The Trump Organization began acquiring and constructing golf courses in 1999.[104] It owned 16 golf courses and resorts worldwide and operated another two as of December 2016[update]. According to Trump's FEC personal financial disclosure, his 2015 golf and resort revenue amounted to $382 million.[105]

From his inauguration until the end of 2019, Trump spent around one out of every five days at one of his golf clubs.[106]

Branding and licensing

After the Trump Organization's financial losses in the early 1990s, it refocused its business on branding and licensing the Trump name for building projects that are owned and operated by other people and companies.[107] In the late 2000s and early 2010s, it expanded this branding and management business to hotel towers located around the world, including Chicago; Las Vegas; Washington, D.C.; Panama City; Toronto; and Vancouver. There were also Trump-branded buildings in Dubai, Honolulu, Istanbul, Manila, Mumbai, and Indonesia.[108]

The Trump name has also been licensed for various consumer products and services, including foodstuffs, apparel, adult learning courses, and home furnishings.[109][110] According to an analysis by The Washington Post, there are more than fifty licensing or management deals involving Trump's name, which have generated at least $59 million in yearly revenue for his companies.[111] By 2018 only two consumer goods companies continued to license his name.[110]

Lawsuits and bankruptcies

As of April 2018[update], Trump and his businesses had been involved in more than 4,000 state and federal legal actions, according to a running tally by USA Today.[112] As of 2016[update], he or one of his companies had been the plaintiff in 1,900 cases and the defendant in 1,450.[113]

While Trump has not filed for personal bankruptcy, his over-leveraged hotel and casino businesses in Atlantic City and New York filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection six times between 1991 and 2009.[114][115] They continued to operate while the banks restructured debt and reduced Trump's shares in the properties.[114][115]

During the 1980s, more than 70 banks had lent Trump $4 billion,[116] but in the aftermath of his corporate bankruptcies of the early 1990s, most major banks declined to lend to him, with only Deutsche Bank still willing to lend money.[117]

In April 2019, the House Oversight Committee issued subpoenas seeking financial details from Trump's banks, Deutsche Bank and Capital One, and his accounting firm, Mazars USA. In response, Trump sued the banks, Mazars, and committee chairman Elijah Cummings to prevent the disclosures.[118][119] In May, DC District Court judge Amit Mehta ruled that Mazars must comply with the subpoena,[120] and judge Edgardo Ramos of the Southern District Court of New York ruled that the banks must also comply.[121][122] Trump's attorneys appealed the rulings,[123] arguing that Congress was attempting to usurp the "exercise of law-enforcement authority that the Constitution reserves to the executive branch".[124][125]

Side ventures

After taking over control of the Trump Organization in 1971, Trump expanded its real estate operations and ventured into other business activities. The company eventually became the umbrella organization for several hundred individual business ventures and partnerships.[126]

In September 1983, Trump purchased the New Jersey Generals, a team in the United States Football League. After the 1985 season, the league folded largely due to Trump's strategy of moving games to a fall schedule where they competed with the NFL for audience, and trying to force a merger with the NFL by bringing an antitrust lawsuit against the organization.[127][128]

Trump's businesses have hosted several boxing matches at the Atlantic City Convention Hall adjacent to and promoted as taking place at the Trump Plaza in Atlantic City, including Mike Tyson's 1988 heavyweight championship fight against Michael Spinks.[129][130] In 1989 and 1990, Trump lent his name to the Tour de Trump cycling stage race, which was an attempt to create an American equivalent of European races such as the Tour de France or the Giro d'Italia.[131]

In the late 1980s, Trump mimicked the actions of Wall Street's so-called corporate raiders, whose tactics had attracted wide public attention. Trump began to purchase significant blocks of shares in various public companies, leading some observers to think he was engaged in the practice called greenmail, or feigning the intent to acquire the companies and then pressuring management to repurchase the buyer's stake at a premium. The New York Times found that Trump initially made millions of dollars in such stock transactions, but later "lost most, if not all, of those gains after investors stopped taking his takeover talk seriously."[132][133][134]

In 1988, Trump purchased the defunct Eastern Air Lines shuttle, with 21 planes and landing rights in New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C. He financed the purchase with $380 million from 22 banks, rebranded the operation the Trump Shuttle, and operated it until 1992. Trump failed to earn a profit with the airline and sold it to USAir.[135]

From 1996 to 2015, Trump owned part of or all the Miss Universe pageants, including Miss USA and Miss Teen USA.[136][137] Due to disagreements with CBS about scheduling, he took both pageants to NBC in 2002.[138][139] In 2007, Trump received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his work as producer of Miss Universe.[140] After NBC and Univision dropped the pageants from their broadcasting lineups in June 2015,[141] Trump bought NBC's share of the Miss Universe Organization and sold the entire company to the William Morris talent agency.[142]

Trump University

In 2004, Trump co-founded a company called Trump University that sold real estate training courses priced from $1,500 to $35,000.[143][144] After New York State authorities notified the company that its use of the word "university" violated state law, its name was changed to Trump Entrepreneur Initiative in 2010.[145]

In 2013, the State of New York filed a $40 million civil suit against Trump University; the suit alleged that the company made false statements and defrauded consumers.[146][147] In addition, two class-action civil lawsuits were filed in federal court; they named Trump personally as well as his companies. Internal documents revealed that employees were instructed to use a hard-sell approach, and former employees said in depositions that Trump University had defrauded or lied to its students.[148][149][150][151][152] Shortly after he won the presidency, Trump agreed to pay a total of $25 million to settle the three cases.[153]

Foundation

The Donald J. Trump Foundation was a U.S.-based private foundation established in 1988 for the initial purpose of giving away proceeds from the book Trump: The Art of the Deal.[154][155] In the foundation's final years its funds mostly came from donors other than Trump, who did not donate any personal funds to the charity from 2009 until 2014.[156] The foundation gave to health care and sports-related charities, as well as conservative groups.[157]

In 2016, The Washington Post reported that the charity had committed several potential legal and ethical violations, including alleged self-dealing and possible tax evasion.[158] Also in 2016, the New York State Attorney General's office said the foundation appeared to be in violation of New York laws regarding charities and ordered it to immediately cease its fundraising activities in New York.[159][160] Trump's team announced in late December 2016 that the Foundation would be dissolved to remove "even the appearance of any conflict with [his] role as President".[161]

In June 2018 the New York attorney general's office filed a civil suit against the foundation, Trump himself, and his adult children, asking for $2.8 million in restitution and additional penalties.[162][163] In December 2018, the foundation ceased operation and disbursed all its assets to other charities.[164] The following November, a New York state judge ordered Trump to pay $2 million to a group of charities for misusing the foundation's funds, in part to finance his presidential campaign.[165][166]

Conflicts of interest

Before being inaugurated as president, Trump moved his businesses into a revocable trust run by his eldest sons and a business associate.[167][168] According to ethics experts, as long as Trump continues to profit from his businesses, the measures taken by Trump do not help to avoid conflicts of interest.[169] Because Trump would have knowledge of how his administration's policies would affect his businesses, ethics experts recommend that Trump sell off his businesses.[168] While Trump said his organization would eschew "new foreign deals", the Trump Organization has since pursued expansions of its operations in Dubai, Scotland, and the Dominican Republic.[169]

Multiple lawsuits have been filed alleging that Trump is violating the Emoluments Clause of the United States Constitution, which forbids presidents from taking money from foreign governments, due to his business interests; they argue that these interests allow foreign governments to influence him.[169][170] Previous presidents in the modern era have either divested their holdings or put them in blind trusts,[167] and he is the first president to be sued over the emoluments clause.[170] According to The Guardian, "NBC News recently calculated that representatives of at least 22 foreign governments – including some facing charges of corruption or human rights abuses such as Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Turkey and the Philippines – seem to have spent funds at Trump properties while he has been president."[171] On October 21, 2019, Trump mocked the Emoluments Clause as "phony".[172]

In 2015, Trump said he "makes a lot of money with" the Saudis and that "they pay me millions and hundreds of millions."[173] And at a political rally, Trump said about Saudi Arabia: "They buy apartments from me. They spend $40 million, $50 million. Am I supposed to dislike them? I like them very much."[174]

In December 2015, Trump said in a radio interview that he had a "conflict of interest" in dealing with Turkey and Turkish president Tayyip Erdoğan because of his Trump Towers Istanbul, saying "I have a little conflict of interest because I have a major, major building in Istanbul and it's a tremendously successful job ... It's called Trump Towers – two towers instead of one ... I've gotten to know Turkey very well".[175][176]

Media career

Books

Trump's first ghostwritten book, The Art of the Deal (1987), was on the New York Times Best Seller list for 48 weeks. According to The New Yorker, "The book expanded Trump's renown far beyond New York City, promoting an image of himself as a successful dealmaker and tycoon." Tony Schwartz, who is credited as co-author, later said he did all the writing, backed by Howard Kaminsky, then-head of Random House, the book's publisher.[177] Two further lesser memoirs were published in 1990 and 1997.

WWF/E

Trump has had a sporadic relationship with professional wrestling promotion World Wrestling Federation/Entertainment and its owners Vince and Linda McMahon since the late 1980s; in 1988 and 1989, WrestleMania IV and V, which took place at the Atlantic City Convention Hall, were billed as taking place at the nearby Trump Plaza.[178][179] He headlined the record-breaking WrestleMania 23 in 2007 and was inducted into the celebrity wing of the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013.[180]

The Apprentice

In 2003, Trump became the co-producer and host of The Apprentice, a reality show in which contestants competed for a one-year management job with the Trump Organization, and Trump weeded out applicants with the catchphrase "You're fired".[181] He later co-hosted The Celebrity Apprentice, in which celebrities competed to win money for charities.[181]

Acting

Trump has made cameo appearances in eight films and television shows[182][183] and performed a song as a Green Acres character with Megan Mullally at the 57th Primetime Emmy Awards in 2005.[184]

Talk shows

Starting in the 1990s, Trump was a guest about 24 times on the nationally syndicated Howard Stern Show.[185] He also had his own short-form talk radio program called Trumped! (one to two minutes on weekdays) from 2004 to 2008.[186][187] In 2011, he was given a weekly unpaid guest commentator spot on Fox & Friends that continued until he started his presidential candidacy in 2015.[188][189]

Political career

Political activities up to 2015

Trump's political party affiliation changed numerous times. He registered as a Republican in Manhattan in 1987, switched to the Reform Party in 1999, the Democratic Party in 2001, and back to the Republican Party in 2009.[190]

In 1987, Trump placed full-page advertisements in three major newspapers,[191] advocating peace in Central America, accelerated nuclear disarmament talks with the Soviet Union, and reduction of the federal budget deficit by making American allies pay "their fair share" for military defense.[192] He ruled out running for local office but not for the presidency.[191]

2000 presidential campaign

In 1999, Trump filed an exploratory committee to seek the nomination of the Reform Party for the 2000 presidential election.[193][194] A July 1999 poll matching him against likely Republican nominee George W. Bush and likely Democratic nominee Al Gore showed Trump with seven percent support.[195] Trump dropped out of the race in February 2000.[196]

2012 presidential speculation

Trump speculated about running for president in the 2012 election, making his first speaking appearance at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in February 2011 and giving speeches in early primary states.[197][198] In May 2011 he announced that he would not run.[197]

Trump's presidential ambitions were generally not taken seriously at the time.[199] Before the 2016 election, The New York Times speculated that Trump "accelerated his ferocious efforts to gain stature within the political world" after Obama lampooned him at the White House Correspondents' Association Dinner in April 2011.[200]

In 2011 the then-superintendent of the New York Military Academy, Jeffrey Coverdale, ordered the then-headmaster of the school, Evan Jones, to give him Trump's academic records so he could keep them secret, according to Jones. Coverdale said he had been asked to add to hand the records over to members of the school's board of trustees who were Mr. Trump's friends, but he refused to give the records to anyone and instead sealed Trump's records on campus. The incident reportedly happened days after Trump demanded the release of President Barack Obama's academic records.[201]

2013–2015

In 2013, Trump spoke at CPAC again;[202] he railed against illegal immigration, bemoaned Obama's "unprecedented media protection", advised against harming Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, and suggested the government "take" Iraq's oil and use the proceeds to pay a million dollars each to families of dead soldiers.[203][204] He spent over $1 million that year to research a possible 2016 candidacy.[205]

In October 2013, New York Republicans circulated a memo suggesting Trump should run for governor of the state in 2014 against Andrew Cuomo. Trump responded that while New York had problems and its taxes were too high, he was not interested in the governorship.[206] A February 2014 Quinnipiac poll had shown Trump losing to the more popular Cuomo by 37 points in a hypothetical election.[207]

According to Trump's attorney Michael Cohen, in May 2015 he sent letters to the New York Military Academy and to Fordham, threatening legal action if the schools ever released Trump's grades or SAT scores; Fordham confirmed receipt of the letter as well as a phone call from a member of the Trump team.[208]

2016 presidential campaign

Republican primaries

On June 16, 2015, Trump announced his candidacy for President of the United States at Trump Tower in Manhattan. In the speech, Trump discussed illegal immigration, offshoring of American jobs, the U.S. national debt, and Islamic terrorism, which all remained large priorities during the campaign. He also announced his campaign slogan: "Make America Great Again".[209] Trump said his wealth would make him immune to pressure from campaign donors.[210] He declared that he was funding his own campaign,[211] but according to The Atlantic, "Trump's claims of self-funding have always been dubious at best and actively misleading at worst."[212]

Trump's campaign was initially not taken seriously by political analysts, but he quickly rose to the top of opinion polls.[213]

On Super Tuesday, Trump received the most votes, and he remained the front-runner throughout the primaries. By March 2016, Trump was poised to win the Republican nomination.[214] After a landslide win in Indiana on May 3, 2016 – which prompted the remaining candidates Cruz and John Kasich to suspend their presidential campaigns – RNC chairman Reince Priebus declared Trump the presumptive Republican nominee.[215]

General election campaign

After becoming the presumptive Republican nominee, Trump shifted his focus to the general election. Trump began campaigning against Hillary Clinton, who became the presumptive Democratic nominee on June 6, 2016.

Clinton had established a significant lead over Trump in national polls throughout most of 2016. In early July, Clinton's lead narrowed in national polling averages following the FBI's re-opening of its investigation into her ongoing email controversy.[216][217][218]

On July 15, 2016, Trump announced his selection of Indiana governor Mike Pence as his running mate.[219] Four days later, the two were officially nominated by the Republican Party at the Republican National Convention.[220] The list of convention speakers and attendees included former presidential nominee Bob Dole, but the other prior nominees did not attend.[221][222]

On September 26, 2016, Trump and Clinton faced off in their first presidential debate, which was held at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York.[223] The second presidential debate was held at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. The final presidential debate was held on October 19 at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Trump's refusal to say whether he would accept the result of the election, regardless of the outcome, drew particular attention, with some saying it undermined democracy.[224][225]

Political positions

Trump's campaign platform emphasized renegotiating U.S.–China relations and free trade agreements such as NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, strongly enforcing immigration laws, and building a new wall along the U.S.–Mexico border. His other campaign positions included pursuing energy independence while opposing climate change regulations such as the Clean Power Plan and the Paris Agreement, modernizing and expediting services for veterans, repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act, abolishing Common Core education standards, investing in infrastructure, simplifying the tax code while reducing taxes for all economic classes, and imposing tariffs on imports by companies that offshore jobs. During the campaign, he also advocated a largely non-interventionist approach to foreign policy while increasing military spending, extreme vetting or banning immigrants from Muslim-majority countries[226] to pre-empt domestic Islamic terrorism, and aggressive military action against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. During the campaign Trump repeatedly called NATO "obsolete".[227][228]

His political positions have been described as populist,[229][230][231] and some of his views cross party lines. For example, his economic campaign plan calls for deregulation and large reductions in income taxes, consistent with Republican Party policies,[232] along with significant infrastructure investment, usually considered a Democratic Party policy.[233] Trump has supported or leaned toward varying political positions over time.[234][235] Politico has described his positions as "eclectic, improvisational and often contradictory",[236] while NBC News counted "141 distinct shifts on 23 major issues" during his campaign.[237]

Campaign rhetoric

In his campaign, Trump said he disdained political correctness; he also said the media had intentionally misinterpreted his words, and he made other claims of adverse media bias.[238][239][240] In part due to his fame, and due to his willingness to say things other candidates would not, and because a candidate who is gaining ground automatically provides a compelling news story, Trump received an unprecedented amount of free media coverage during his run for the presidency, which elevated his standing in the Republican primaries.[241]

Fact-checking organizations have denounced Trump for making a record number of false statements compared to other candidates.[242][243][244] At least four major publications – Politico, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times – have pointed out lies or falsehoods in his campaign statements, with the Los Angeles Times saying that "Never in modern presidential politics has a major candidate made false statements as routinely as Trump has".[245] NPR said Trump's campaign statements were often opaque or suggestive.[246]

Trump's penchant for hyperbole is believed to have roots in the New York real estate scene, where Trump established his wealth and where puffery abounds.[247] Trump adopted his ghostwriter's phrase "truthful hyperbole" to describe his public speaking style.[247][248]

Support from the far right

According to Michael Barkun, the Trump campaign was remarkable for bringing fringe ideas, beliefs, and organizations into the mainstream.[249] During his presidential campaign, Trump was accused of pandering to white supremacists.[250][251][252] He retweeted open racists,[253][254] and repeatedly refused to condemn David Duke, the Ku Klux Klan or white supremacists, in an interview on CNN's State of the Union, saying he would first need to "do research" because he knew nothing about Duke or white supremacists.[255][256] Duke himself enthusiastically supported Trump throughout the 2016 primary and election, and has said he and like-minded people voted for Trump because of his promises to "take our country back".[257][258]

After repeated questioning by reporters, Trump said he disavowed David Duke and the KKK.[259] Trump said on MSNBC's Morning Joe: "I disavowed him. I disavowed the KKK. Do you want me to do it again for the 12th time? I disavowed him in the past, I disavow him now."[259]

The alt-right movement coalesced around Trump's candidacy,[260] due in part to its opposition to multiculturalism and immigration.[261][262][263] Members of the alt-right enthusiastically supported Trump's campaign.[264] In August 2016, he appointed Steve Bannon – the executive chairman of Breitbart News – as his campaign CEO; Bannon described Breitbart News as "the platform for the alt-right".[265] In an interview days after the election, Trump condemned supporters who celebrated his victory with Nazi salutes.[266][267]

Financial disclosures

As a presidential candidate, Trump disclosed details of his companies, assets, and revenue sources to the extent required by the FEC. His 2015 report listed assets above $1.4 billion and outstanding debts of at least $265 million.[59][268] The 2016 form showed little change.[105]

Trump has not released his tax returns, contrary to the practice of every major candidate since 1976 and his promises in 2014 and 2015 to do so if he ran for office.[269][270] He said his tax returns were being audited (in actuality, audits do not prevent release of tax returns), and his lawyers had advised him against releasing them.[271] Trump has told the press his tax rate was none of their business, and that he tries to pay "as little tax as possible".[272]

In October 2016, portions of Trump's state filings for 1995 were leaked to a reporter from The New York Times. They show that Trump declared a loss of $916 million that year, which could have let him avoid taxes for up to 18 years. During the second presidential debate, Trump acknowledged using the deduction, but declined to provide details such as the specific years it was applied.[273]

On March 14, 2017, the first two pages of Trump's 2005 federal income tax returns were leaked to MSNBC. The document states that Trump had a gross adjusted income of $150 million and paid $38 million in federal taxes. The White House confirmed the authenticity of the documents.[274][275]

In April 2019, the House Ways and Means Committee made a formal request to the Internal Revenue Service for Trump's personal and business tax returns from 2013 to 2018.[276] Two deadlines to provide the returns were missed, then Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin in May 2019 ultimately denied the request.[277][278][279] Committee chairman Richard Neal then subpoenaed the Treasury Department and the IRS for the returns.[280] These subpoenas were also defied in May 2019.[281] A fall 2018 draft IRS legal memo asserted that tax returns must be provided to Congress upon request, unless a president invokes executive privilege. Congress need not justify the request, the memo stated, contradicting the administration's justification that a legislative purpose is needed to produce the tax returns.[282] Mnuchin asserted the memo actually addressed a different matter.[283]

Election to the presidency

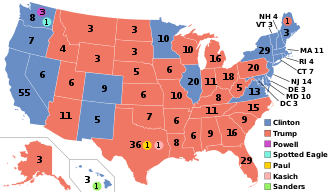

On November 8, 2016, Trump received 306 pledged electoral votes versus 232 for Clinton. The official counts were 304 and 227 respectively, after defections on both sides.[284] Trump received nearly 2.9 million fewer popular votes than Clinton, which made him the fifth person to be elected president while losing the popular vote.[285][c] Clinton was ahead nationwide with 65,853,514 votes (48.18%) to 62,984,828 votes (46.09%).[288]

Trump's victory was considered a stunning political upset by most observers, as polls had consistently showed Hillary Clinton with a nationwide – though diminishing – lead, as well as a favorable advantage in most of the competitive states. Trump's support had been modestly underestimated throughout his campaign,[289] and many observers blamed errors in polls, partially attributed to pollsters overestimating Clinton's support among well-educated and nonwhite voters, while underestimating Trump's support among white working-class voters.[290] The polls were relatively accurate,[291] but media outlets and pundits alike showed overconfidence in a Clinton victory despite a large number of undecided voters and a favorable concentration of Trump's core constituencies in competitive states.[292]

Trump won 30 states, including Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which had been considered a blue wall of Democratic strongholds since the 1990s. Clinton won 20 states and the District of Columbia. Trump's victory marked the return of a Republican White House combined with control of both chambers of Congress.[citation needed]

Trump is the wealthiest president in U.S. history, even after adjusting for inflation,[293] and the oldest person to take office as president.[294] He is also the first president who did not serve in the military or hold elective or appointed government office prior to being elected.[295][296] Of the 43[d] previous presidents, 38 had held prior elective office, two had not held elective office but had served in the Cabinet, and three had never held public office but had been commanding generals.[296]

Protests

Some rallies during the primary season were accompanied by protests or violence, including attacks on Trump supporters and vice versa both inside and outside the venues.[298][299][300] Trump's election victory sparked protests across the United States, in opposition to his policies and his inflammatory statements. Trump initially said on Twitter that these were "professional protesters, incited by the media", and were "unfair", but he later tweeted, "Love the fact that the small groups of protesters last night have passion for our great country."[301][302]

In the weeks following Trump's inauguration, massive anti-Trump demonstrations took place, such as the Women Marches, which gathered 2,600,000 people worldwide,[303] including 500,000 in Washington alone.[304] Marches against his travel ban began across the country on January 29, 2017, just nine days after his inauguration.[305]

2020 presidential campaign

Trump signaled his intention to run for a second term by filing with the FEC within a few hours of assuming the presidency.[306] This transformed his 2016 election committee into a 2020 reelection one.[307] Trump marked the official start of the campaign with a rally in Melbourne, Florida, on February 18, 2017, less than a month after taking office.[308] By January 2018, Trump's reelection committee had $22 million in hand,[309] and it had raised a total amount exceeding $67 million by December 2018.[310] Trump became the Republican presumptive nominee on March 17, 2020, after securing a majority of pledged delegates.[311]

Presidency

Early actions

Trump was inaugurated as the 45th president of the United States on January 20, 2017. During his first week in office, he signed six executive orders: interim procedures in anticipation of repealing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy, unlocking the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipeline construction projects, reinforcing border security, and beginning the planning and design process to construct a wall along the U.S. border with Mexico.[312]

Upon inauguration, Trump delegated the management of his real estate business to his sons Eric and Don Jr.[313] His daughter Ivanka resigned from the Trump Organization and moved to Washington, D.C., with her husband Jared Kushner. She serves as an assistant to the President,[314] and he is a Senior Advisor in the White House.[315]

On January 31, Trump nominated U.S. Appeals Court judge Neil Gorsuch to fill the seat on the Supreme Court previously held by Justice Antonin Scalia until his death on February 13, 2016.[316]

Domestic policy

Economy and trade

The economic expansion that began in June 2009 continued through Trump's first three years in office. Throughout his presidency, he has repeatedly and falsely characterized the economy as the best in American history.[317]

In December 2017, Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which cut the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, lowered personal tax brackets, increased child tax credit, doubled the estate tax exemption to $11.2 million, and limited the state and local tax deduction to $10,000.[318]

Trump is a skeptic of multilateral trade deals, as he believes they indirectly incentivize unfair trade practices that then tend to go unpoliced. He favors bilateral trade deals, as they allow one party to pull out if the other party is believed to be behaving unfairly. Trump favors neutral or positive balances of trade over negative balances of trade, also known as a "trade deficit". Trump adopted his current skeptical views toward trade liberalization in the 1980s, and he sharply criticized NAFTA during the Republican primary campaign in 2015.[319][320][321] He withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations,[322] imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum imports,[323] and launched a trade war with China by sharply increasing tariffs on 818 categories (worth $50 billion) of Chinese goods imported into the U.S.[324][325] On several occasions, Trump has said incorrectly that these import tariffs are paid by China into the U.S. Treasury.[326]

Energy and climate

Trump rejects the scientific consensus on climate change.[327][328] Since his election Trump has made large budget cuts to programs that research renewable energy and has rolled back Obama-era policies directed at curbing climate change.[329] In June 2017, Trump announced the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement, making the U.S. the only nation in the world to not ratify the agreement.[330] At the 2019 G7 summit, Trump skipped the sessions on climate change but said afterward during a press conference that he is an environmentalist.[331]

Trump has rolled back federal regulations aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, water pollution, and the usage of toxic substances. He relaxed environmental standards for federal infrastructure projects, while expanding permitted areas for drilling and resource extraction. Trump also weakened protections for animals.[332] Trump's energy policies aimed to boost the production and exports of coal, oil, and natural gas.[333]

Government size and deregulation

Trump's early policies have favored rollback and dismantling of government regulations. He has signed 15 Congressional Review Act disapproval resolutions to allow Congress to repeal executive regulations, the second President to sign any such resolutions after the first CRA resolution was passed in 2001, and the first President to sign more than one such resolution.[334] During his first six weeks in office, he delayed, suspended or reversed ninety federal regulations.[335][336]

On January 30, 2017, Trump signed Executive Order 13771, which directed that for every new regulation administrative agencies issue "at least two existing regulations be identified for elimination".[337][338] Agency defenders expressed opposition to Trump's criticisms, saying the bureaucracy exists to protect people against well-organized, well-funded interest groups.[339]

Health care

During his campaign, Trump repeatedly vowed to repeal and replace Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or "Obamacare").[340] Shortly after taking office, he urged Congress to repeal and replace it. In May of that year, the House voted to repeal it.[341] His first action as President was Executive Order 13765, which increased flexibility "to the maximum extent permitted by law" for the Cabinet to issue waivers, deferrals, and exemptions for the law while attempting to give states more flexibility.[342] Executive Order 13813 was subsequently issued, designed to reduce regulations imposed under Obamacare by increasing competition.[343] Trump has expressed a desire to "let Obamacare fail", and the Trump administration has cut the ACA enrollment period in half and drastically reduced funding for advertising and other ways to encourage enrollment.[344][345][346] The 2017 tax bill effectively repealed the ACA's individual health insurance mandate in 2019,[347][348][349] and a budget bill Trump signed in 2019 repealed the Cadillac plan tax, medical device tax, and tanning tax.[350][351] As president, Trump has falsely claimed he saved the coverage of pre-existing conditions provided by ACA, while his administration declined to challenge a lawsuit that would eliminate it.[352] As a 2016 candidate, Trump promised to protect funding for Medicare and other social safety-net programs, but in January 2020 he suggested he was willing to consider cuts to such programs.[353]

Social issues

Trump favored modifying the 2016 Republican platform opposing abortion, to allow for exceptions in cases of rape, incest, and circumstances endangering the health of the mother.[354] He has said he is committed to appointing "pro-life" justices.[355] He says he personally supports "traditional marriage"[356] but considers the nationwide legality of same-sex marriage a "settled" issue.[355] Despite the statement by Trump and the White House saying they would keep in place a 2014 executive order from the Obama administration which created federal workplace protections for LGBT people,[357] in March 2017, the Trump administration rolled back key components of the Obama administration's workplace protections for LGBT people.[358]

Trump supports a broad interpretation of the Second Amendment and says he is opposed to gun control in general,[359][360] although his views have shifted over time.[361] Trump opposes legalizing recreational marijuana but supports legalizing medical marijuana.[362] He favors capital punishment,[363][364] as well as the use of waterboarding and "a hell of a lot worse" methods.[365][366]

Pardons and commutation

On February 18, 2020, Trump pardoned white-collar criminals Michael Milken, Bernard Kerik, and Edward J. DeBartolo Jr., and commuted former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich's 14-year corruption sentence.[367][368]

On February 19, 2020, Assange's barrister told the court that Dana Rohrabacher, who was then a Republican Representative in the House, had visited Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in August 2017 and, on instructions from Trump, offered a pardon if Assange said Russia had no role in the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leaks. The district judge hearing the case ruled that the evidence is admissible in Assange's legal attempts to block extradition to the U.S. "It is a complete fabrication", the White House Press Secretary, Stephanie Grisham, told reporters. "The president barely knows Dana Rohrabacher other than he's an ex-congressman. He's never spoken to him on this subject or almost any subject." Trump had previously invited Rohrabacher to the White House in April 2017.[369]

Immigration

Trump's proposed immigration policies were a topic of bitter and contentious debate during the campaign. He promised to build a more substantial wall on the Mexico–United States border to keep out illegal immigrants and vowed Mexico would pay for it.[370] He pledged to massively deport illegal immigrants residing in the United States,[371] and criticized birthright citizenship for creating "anchor babies".[372] He said deportation would focus on criminals, visa overstays, and security threats.[373] As president, he frequently described illegal immigration as an "invasion" and conflated immigrants with the gang MS-13, though research shows undocumented immigrants have a lower crime rate than native-born Americans.[374]

Travel ban

Following the November 2015 Paris attacks, Trump made a controversial proposal to ban Muslim foreigners from entering the United States until stronger vetting systems could be implemented.[375][376][377] He later reframed the proposed ban to apply to countries with a "proven history of terrorism".[378][379][380]

On January 27, 2017, Trump signed Executive Order 13769, which suspended admission of refugees for 120 days and denied entry to citizens of Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen for 90 days, citing security concerns. The order was imposed without warning and took effect immediately.[381] Confusion and protests caused chaos at airports.[382][383] Sally Yates, the acting Attorney General, directed Justice Department lawyers not to defend the executive order, which she deemed unenforceable and unconstitutional;[384] Trump immediately dismissed her.[385] Multiple legal challenges were filed against the order, and on February 5 a federal judge in Seattle blocked its implementation nationwide.[386][387] On March 6, Trump issued a revised order, which excluded Iraq, gave specific exemptions for permanent residents, and removed priorities for Christian minorities.[388][381] Again federal judges in three states blocked its implementation.[389] On June 26, 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that the ban could be enforced on visitors who lack a "credible claim of a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States".[390]

The temporary order was replaced by Presidential Proclamation 9645 on September 24, 2017, which permanently restricts travel from the originally targeted countries except Iraq and Sudan, and further bans travelers from North Korea and Chad, along with certain Venezuelan officials.[391] After lower courts partially blocked the new restrictions, the Supreme Court allowed the September version to go into full effect on December 4,[392] and ultimately upheld the travel ban in a June 2019 ruling.[393]

Family separation at border

In April 2018, Trump enacted a "zero tolerance" immigration policy that temporarily took adults irregularly entering the U.S. into custody for criminal prosecution and forcibly separated children from parents, eliminating the policy of previous administrations, which had made exceptions for families with children.[394][395] By mid-June, more than 2,300 children had been placed in shelters, including Department of Health and Human Services-designated "tender age" shelters for children under thirteen,[396] culminating in demands from Democrats, Republicans, Trump allies, and religious groups that the policy be rescinded.[397] Trump falsely asserted that his administration was merely following the law.[398][399][400] On June 20, Trump signed an executive order to end family separations at the U.S. border.[401] On June 26 a federal judge in San Diego issued a preliminary injunction requiring the Trump administration to stop detaining immigrant parents separately from their minor children, and to reunite family groups who had been separated at the border.[402]

2018–2019 federal government shutdown

On December 22, 2018, the federal government was partially shut down after Trump declared that any funding extension must include $5.6 billion in federal funds for a U.S.–Mexico border wall to partly fulfill his campaign promise.[403] The shutdown was caused by a lapse in funding for nine federal departments, affecting about one-fourth of federal government activities.[404] Trump said he would not accept any bill that did not include funding for the wall, and Democrats, who control the House, said they would not support any bill that does. Senate Republicans have said they will not advance any legislation that Trump would not sign.[405] In earlier negotiations with Democratic leaders, Trump commented that he would be "proud to shut down the government for border security".[406]

Foreign policy

Trump has been described as a non-interventionist[407][408] and an American nationalist.[409] He has repeatedly said he supports an "America First" foreign policy.[410] He supports increasing United States military defense spending,[409] but favors decreasing United States spending on NATO and in the Pacific region.[411] He says America should look inward, stop "nation building", and re-orient its resources toward domestic needs.[408]

His foreign policy has been marked by repeated praise and support of neo-nationalist and authoritarian strongmen and criticism of democratically-led governments.[412] Trump has cited China's president Xi Jinping,[413] Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte,[414] Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi,[415] Turkey's president Tayyip Erdoğan,[416] King Salman of Saudi Arabia,[417] Italy's prime minister Giuseppe Conte,[418] Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro,[419] Indian prime minister Narendra Modi,[420] and Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán as examples of good leaders.[421] Trump has also praised Poland under the EU-skeptic, anti-immigrant Law and Justice party (PiS) as a defender of Western civilization.[422][423]

ISIS and war

In April 2017, Trump ordered a missile strike against a Syrian airfield in retaliation for the Khan Shaykhun chemical attack.[424] According to investigative journalist Bob Woodward, Trump had ordered his defense secretary James Mattis to assassinate Syrian president Bashar al-Assad after the chemical attack, but Mattis declined; Trump denied doing so.[425] In April 2018, he announced missile strikes against Assad's regime, following a suspected chemical attack near Damascus.[426]

In December 2018, Trump declared "we have won against ISIS," and ordered the withdrawal of all troops from Syria, contradicting Department of Defense assessments.[427][428][429] Mattis resigned the next day over disagreements in foreign policy, calling this decision an abandonment of Kurd allies who had played a key role in fighting ISIS.[430] One week after his announcement, Trump said he would not approve any extension of the American deployment in Syria.[431] On January 6, 2019, national security advisor John Bolton announced America would remain in Syria until ISIS is eradicated and Turkey guarantees it will not strike America's Kurdish allies.[432]

Trump actively supported the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and signed a $110 billion agreement to sell arms to Saudi Arabia.[433][434][435] Trump also praised his relationship with Saudi Arabia's powerful Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman.[433]

U.S. troop numbers in Afghanistan increased from 8,500 to 14,000, as of January 2017[update],[436] reversing Trump's pre-election position critical of further involvement in Afghanistan.[437] U.S. officials said then that they aimed to "force the Taliban to negotiate a political settlement"; in January 2018, however, Trump spoke against talks with the Taliban.[438]

In October 2019, after Trump spoke to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the White House acknowledged that Turkey would be carrying out a planned military offensive into northern Syria; as such, U.S. troops in northern Syria were withdrawn from the area to avoid interference with that operation. The statement also passed responsibility for the area's captured ISIS fighters to Turkey.[439] In the following days, Trump suggested the Kurds intentionally released ISIS prisoners in order to gain sympathy, suggested they were fighting only for their own financial interests, suggested some of them were worse than ISIS, and termed them "no angels".[440]

Congress members of both parties denounced the move, including Republican allies of Trump such as Senator Lindsey Graham. They argued that the move betrayed the American-allied Kurds, and would benefit ISIS, Turkey, Russia, Iran, and Bashar al-Assad's Syrian regime.[441] Trump defended the move, citing the high cost of supporting the Kurds, and the lack of support from the Kurds in past U.S. wars.[442][443] After the U.S. pullout, Turkey proceeded to attack Kurdish-controlled areas in northeastern Syria.[444] On October 16, the United States House of Representatives, in a rare bipartisan vote of 354 to 60, "condemned" Trump's withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria for "abandoning U.S. allies, undermining the struggle against ISIS, and spurring a humanitarian catastrophe".[445][446]

Iran

Trump has described the regime in Iran as "the rogue regime", although he has also asserted he does not seek regime change.[447][448] He has repeatedly criticized the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA or "Iran nuclear deal") that was negotiated with the United States, Iran, and five other world powers in 2015, calling it "terrible" and saying the Obama administration had negotiated the agreement "from desperation".[449][450][451]

Following Iran's ballistic missile tests on January 29, 2017, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on 25 Iranian individuals and entities in February 2017.[452][453][454] Trump reportedly lobbied "dozens" of European officials against doing business with Iran during the May 2017 Brussels summit; this likely violated the terms of the JCPOA, under which the U.S. may not pursue "any policy specifically intended to directly and adversely affect the normalization of trade and economic relations with Iran". The Trump administration certified in July 2017 that Iran had upheld its end of the agreement.[455] On August 2, 2017, Trump signed into law the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) that grouped together sanctions against Iran, Russia, and North Korea.[456] On May 18, 2018, Trump announced the United States' unilateral departure from the JCPOA.[450]

In May 2017, strained relations between the U.S. and Iran escalated when Trump deployed military bombers and a carrier group to the Persian Gulf. Trump hinted at war on social media, provoking a response from Iran for what Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif called "genocidal taunts".[457][458][459] Trump and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman are allies in the conflict with Iran.[460] Trump approved the deployment of additional U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates following the attack on Saudi oil facilities which the United States has blamed on Iran.[461] He also ordered a targeted U.S. airstrike on January 2, 2020, which killed Iranian Major General and IRGC Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani and Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, as well as eight other people.[462] Trump publicly threatened to attack Iranian cultural sites if Iran retaliated; such an attack by the U.S. would violate international law.[463] On January 8, 2020, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps launched multiple ballistic missiles on two U.S. airbases in Iraq.[464]

Israel

Trump has supported the policies of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.[465] He officially recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel on December 6, 2017, despite criticism and warnings from world leaders. He subsequently opened a new U.S. embassy in Jerusalem in May 2018.[466][467] The United Nations General Assembly condemned the move, adopting a resolution that "calls upon all States to refrain from the establishment of diplomatic missions in the Holy City of Jerusalem".[468][469] In March 2019, Trump reversed decades of U.S. policy by recognizing Israel's annexation of the Golan Heights,[470] a move condemned by the European Union and the Arab League.[471]

China

Before and during his presidency, Trump has repeatedly accused China of taking unfair advantage of the U.S.[472] During his presidency, Trump has launched a trade war against China, sanctioned Huawei for its alleged ties to Iran,[473] significantly increased visa restrictions on Chinese nationality students and scholars[474][475] and classified China as a "currency manipulator".[476] In the wake of the significant deterioration of relations, many political observers have warned against a new cold war between China and the U.S.[477][478][479]

North Korea

In 2017, North Korea's nuclear weapons became increasingly seen as a serious threat to the United States.[480][481][482] In August, Trump dramatically escalated his rhetoric against North Korea, warning that further provocations would be met with "fire and fury like the world has never seen".[483] In response, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un threatened to direct a missile test toward Guam.[484]

On June 12, 2018, Trump and Kim held a summit in Singapore,[485] resulting in North Korea affirming its intention "to work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula".[486][487] A second summit took place in February 2019, in Hanoi, Vietnam.[488] It ended abruptly without an agreement, both sides blaming each other and offering differing accounts of the negotiations.[488][489] On June 30, 2019, Trump, Kim, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in held brief talks in the Korean Demilitarized Zone, marking the first time a sitting U.S. president had set foot on North Korean soil. They agreed to resume negotiations.[490] Bilateral talks began in Stockholm on October 5, but broke down after one day.[491]

Russia

During his campaign and as president, Trump has repeatedly asserted that he desires better relations with Russia,[492][493] and he has praised Russian president Vladimir Putin as a strong leader.[494][495] He also said Russia could help the U.S. in its fight against ISIS.[496] According to Putin and some political experts and diplomats, the U.S.–Russian relations, which were already at the lowest level since the end of the Cold War, have further deteriorated since Trump took office in January 2017.[497][498][499]

After Trump met Putin at the Helsinki Summit on July 16, 2018, Trump drew bipartisan criticism for siding with Putin's denial of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, rather than accepting the findings of the United States intelligence community.[500][501][502]

Trump has criticized Russia about Syria,[503] Ukraine,[504] North Korea,[505] Venezuela,[506] and the Skripal poisoning,[507] but has sent mixed messages regarding Crimea.[508][509][510] He forbade U.S. oil companies from drilling in Russia.[511]

Cuba

In November 2017, the Trump administration tightened the rules on trade with Cuba and individual visits to the country, undoing the Obama administration's loosening of restrictions. According to an administration official, the new rules were intended to hinder trade with businesses with ties to the Cuban military, intelligence and security services.[512]

Venezuela

On August 11, 2017, Trump said he is "not going to rule out a military option" to confront the government of Nicolás Maduro.[513] In September 2018, Trump called "for the restoration of democracy in Venezuela" and said that "socialism has bankrupted the oil-rich nation and driven its people into abject poverty."[514] On January 23, 2019, Maduro announced that Venezuela was breaking ties with the United States following Trump's announcement of recognizing Juan Guaidó, the Venezuelan opposition leader, as the interim president of Venezuela.[515]

NATO

As a candidate, Trump questioned whether he, as president, would automatically extend security guarantees to NATO members,[516] and suggested he might leave NATO unless changes are made to the alliance.[517] As president, he reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to NATO in March 2017.[518] However, he has repeatedly accused fellow NATO members of paying less than their fair share of the expenses of the alliance.[519]

In January 2019, The New York Times quoted senior administration officials as saying Trump has privately suggested on multiple occasions that the United States should withdraw from NATO.[520] The next day Trump said the United States is going to "be with NATO one hundred percent" but repeated that the other countries have to "step up" and pay more.[521]

Personnel

The Trump administration has been characterized by high turnover, particularly among White House staff. By the end of Trump's first year in office, 34 percent of his original staff had resigned, been fired, or been reassigned.[522] As of early July 2018[update], 61 percent of Trump's senior aides had left[523] and 141 staffers had left in the past year.[524] Both figures set a record for recent presidents – more change in the first 13 months than his four immediate predecessors saw in their first two years.[525] Notable early departures included National Security Advisor Mike Flynn (after just 25 days in office), Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, replaced by retired Marine general John F. Kelly on July 28, 2017,[526] and Press Secretary Sean Spicer.[525] Close personal aides to Trump such as Steve Bannon, Hope Hicks, John McEntee and Keith Schiller, have quit or been forced out.[527]

Trump's cabinet nominations included U.S. senator from Alabama Jeff Sessions as Attorney General,[528] financier Steve Mnuchin as Secretary of the Treasury,[529] retired Marine Corps general James Mattis as Secretary of Defense,[530] and ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State.[531] Trump also brought on board politicians who had opposed him during the presidential campaign, such as neurosurgeon Ben Carson as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development,[532] and South Carolina governor Nikki Haley as Ambassador to the United Nations.[533]

Two of Trump's 15 original cabinet members were gone within 15 months: Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price was forced to resign in September 2017 due to excessive use of private charter jets and military aircraft, and Trump replaced Secretary of State Rex Tillerson with Mike Pompeo in March 2018 over disagreements on foreign policy.[534][527] EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt resigned in July 2018 amidst multiple investigations into his conduct,[535] while Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke resigned five months later as he also faced multiple investigations.[536]

Trump has been slow to appoint second-tier officials in the executive branch, saying many of the positions are unnecessary. In October 2017, there were still hundreds of sub-cabinet positions without a nominee.[537] By January 8, 2019, of 706 key positions, 433 had been filled (61%) and Trump had no nominee for 264 (37%).[538]

Dismissal of James Comey

On May 9, 2017, Trump dismissed FBI director James Comey. He first attributed this action to recommendations from Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Deputy AG Rod Rosenstein,[539] which criticized Comey's conduct in the investigation about Hillary Clinton's emails.[540] On May 11, Trump said he was concerned with the ongoing "Russia thing"[541] and that he had intended to fire Comey earlier, regardless of DOJ advice.[542]

According to a Comey memo of a private conversation on February 14, 2017, Trump said he "hoped" Comey would drop the investigation into National Security Advisor Michael Flynn.[543] In March and April, Trump had told Comey the ongoing suspicions formed a "cloud" impairing his presidency,[544] and asked him to publicly state that he was not personally under investigation.[545] He also asked intelligence chiefs Dan Coats and Michael Rogers to issue statements saying there was no evidence that his campaign colluded with Russia during the 2016 election.[546] Both refused, considering this an inappropriate request, although not illegal.[547] Comey eventually testified on June 8 that, while he was director, the FBI investigations had not targeted Trump himself.[544][548]

Coronavirus pandemic

In December 2019, an outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China, spreading worldwide within weeks.[549][550] The first confirmed case in the United States was reported on January 20, 2020.[551] On January 31, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar announced a partial ban on travel to the U.S. from China, effective February 2.[552] Trump was slow to address the pandemic, initially dismissing the imminent threat and ignoring calls for action from government health experts and Secretary Azar.[553][554][555][556] Throughout January and February, he rejected persistent public health warnings from officials within his administration, focusing instead on economic and political considerations of the outbreak.[555] He continued to claim that a vaccine was months away, although HHS and CDC officials had repeatedly told him it would take 12–18 months to develop a vaccine.[557][558] Trump also exaggerated the availability of testing for the virus, falsely claiming "Anybody that wants a test can get a test," even though availability of tests was severely limited.[559][560]

On March 6, Trump signed the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act into law, which provided $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies.[561] On March 11, Trump announced partial travel restrictions for most of Europe, effective March 13.[562] That same day, Trump gave his first serious assessment of the virus ("horrible") in a nationwide Oval Office address, however he also sought to downplay its impact, saying the outbreak was "a temporary moment" and that there was no financial crisis.[563] On March 13 he declared a national emergency, freeing up federal resources.[564][565][566] In a March 16 press conference, Trump acknowledged for the first time that the pandemic was "not under control"; that the situation was "bad"; and that months of disruption to daily lives and a recession might occur.[567]