Google: Difference between revisions

TurboLazer (talk | contribs) →2010–present: Google Stadia |

m Added the dollar equivalent of a stated Euro amount. |

||

| Line 431: | Line 431: | ||

On January 21, 2019, French data regulator [[CNIL]] imposed a record €50 million fine on Google for breaching the European Union’s [[General Data Protection Regulation]]. The judgment claimed Google had failed to sufficiently inform users of its methods for collecting data to personalize advertising. Google issued a statement saying it was “deeply committed” to transparency and was “studying the decision” before determining its response.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Fox |first1=Chris |title=Google hit with £44m GDPR fine |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46944696 |website=BBC |accessdate=22 January 2019 |date=21 January 2019}}</ref> |

On January 21, 2019, French data regulator [[CNIL]] imposed a record €50 million fine on Google for breaching the European Union’s [[General Data Protection Regulation]]. The judgment claimed Google had failed to sufficiently inform users of its methods for collecting data to personalize advertising. Google issued a statement saying it was “deeply committed” to transparency and was “studying the decision” before determining its response.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Fox |first1=Chris |title=Google hit with £44m GDPR fine |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46944696 |website=BBC |accessdate=22 January 2019 |date=21 January 2019}}</ref> |

||

On March 20, 2019, the European Commission imposed a €1.49 |

On March 20, 2019, the European Commission imposed a €1.49 billion ($1.69 billion) fine on Google for preventing rivals from being able to “compete and innovate fairly” in the online advertising market<ref>{{cite web |title=Europe hits Google with a third, $1.7 billion antitrust fine |url=https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/20/tech/google-eu-antitrust/index.html |website=CNN |accessdate=21 March 2019}}</ref>. European Union competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said Google had violated EU antitrust rules by “imposing anti-competitive contractual restrictions on third-party websites” that required them to exclude search results from Google’s rivals. Kent Walker, Google’s senior vice-president of global affairs, said the company had “already made a wide range of changes to our products to address the Commission’s concerns,” and that "we'll be making further updates to give more visibility to rivals in Europe."<ref>{{cite web |last1=Reid |first1=David |title=EU regulators hit Google with $1.7 billion fine for blocking ad rivals |url=https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/20/eu-vestager-hits-google-with-fine-for.html |website=CNBC.com |accessdate=20 March 2019}}</ref> |

||

== Criticism and controversy == |

== Criticism and controversy == |

||

Revision as of 00:26, 23 March 2019

Google's logo since 2015[update] | |

Google's headquarters, the Googleplex | |

| Formerly | Google Inc. (1998–2017) |

|---|---|

| Company type | Subsidiary |

| Industry |

|

| Founded | September 4, 1998 in Menlo Park, California[1][2] |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, , U.S.[3] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | List of Google products |

Number of employees | 98,771[4] (Q4 2018[update]) |

| Parent | Alphabet Inc. (2015–present) |

| Subsidiaries | List of subsidiaries |

| Website | google |

Google LLC[5] is an American multinational technology company that specializes in Internet-related services and products, which include online advertising technologies, search engine, cloud computing, software, and hardware. It is considered one of the Big Four technology companies, alongside Amazon, Apple and Facebook.[6][7]

Google was founded in 1998 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin while they were Ph.D. students at Stanford University in California. Together they own about 14 percent of its shares and control 56 percent of the stockholder voting power through supervoting stock. They incorporated Google as a privately held company on September 4, 1998. An initial public offering (IPO) took place on August 19, 2004, and Google moved to its headquarters in Mountain View, California, nicknamed the Googleplex. In August 2015, Google announced plans to reorganize its various interests as a conglomerate called Alphabet Inc. Google is Alphabet's leading subsidiary and will continue to be the umbrella company for Alphabet's Internet interests. Sundar Pichai was appointed CEO of Google, replacing Larry Page who became the CEO of Alphabet.

The company's rapid growth since incorporation has triggered a chain of products, acquisitions, and partnerships beyond Google's core search engine (Google Search). It offers services designed for work and productivity (Google Docs, Google Sheets, and Google Slides), email (Gmail/Inbox), scheduling and time management (Google Calendar), cloud storage (Google Drive), social networking (Google+), instant messaging and video chat (Google Allo, Duo, Hangouts), language translation (Google Translate), mapping and navigation (Google Maps, Waze, Google Earth, Street View), video sharing (YouTube), note-taking (Google Keep), and photo organizing and editing (Google Photos). The company leads the development of the Android mobile operating system, the Google Chrome web browser, and Chrome OS, a lightweight operating system based on the Chrome browser. Google has moved increasingly into hardware; from 2010 to 2015, it partnered with major electronics manufacturers in the production of its Nexus devices, and it released multiple hardware products in October 2016, including the Google Pixel smartphone, Google Home smart speaker, Google Wifi mesh wireless router, and Google Daydream virtual reality headset. Google has also experimented with becoming an Internet carrier (Google Fiber, Project Fi, and Google Station).[8]

Google.com is the most visited website in the world.[9] Several other Google services also figure in the top 100 most visited websites, including YouTube and Blogger. Google is the most valuable brand in the world as of 2017,[update][10] but has received significant criticism involving issues such as privacy concerns, tax avoidance, antitrust, censorship, and search neutrality. Google's mission statement is "to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful", and its unofficial slogan was "Don't be evil" until the phrase was removed from the company's code of conduct around May 2018.[11][12]

History

Google began in January 1996 as a research project by Larry Page and Sergey Brin when they were both PhD students at Stanford University in Stanford, California.[14]

While conventional search engines ranked results by counting how many times the search terms appeared on the page, the two theorized about a better system that analyzed the relationships among websites.[15] They called this new technology PageRank; it determined a website's relevance by the number of pages, and the importance of those pages that linked back to the original site.[16][17]

Page and Brin originally nicknamed their new search engine "BackRub", because the system checked backlinks to estimate the importance of a site.[18][19][20] Eventually, they changed the name to Google; the name of the search engine originated from a misspelling of the word "googol",[21][22] the number 1 followed by 100 zeros, which was picked to signify that the search engine was intended to provide large quantities of information.[23] Originally, Google ran under Stanford University's website, with the domains google.stanford.edu[24] and z.stanford.edu.[25]

The domain name for Google was registered on September 15, 1997,[26] and the company was incorporated on September 4, 1998. It was based in the garage of a friend (Susan Wojcicki[14]) in Menlo Park, California. Craig Silverstein, a fellow PhD student at Stanford, was hired as the first employee.[14][27][28]

Financing (1998) and initial public offering (2004)

Google was initially funded by an August 1998 contribution of $100,000 from Andy Bechtolsheim, co-founder of Sun Microsystems; the money was given before Google was incorporated.[30] Google received money from three other angel investors in 1998: Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, Stanford University computer science professor David Cheriton, and entrepreneur Ram Shriram.[31] Between these initial investors, friends, and family Google raised around 1 million dollars, which is what allowed them to open up their original shop in Menlo Park, California [32]

After some additional, small investments through the end of 1998 to early 1999,[31] a new $25 million round of funding was announced on June 7, 1999,[33] with major investors including the venture capital firms Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital.[30]

Early in 1999, Brin and Page decided they wanted to sell Google to Excite. They went to Excite CEO George Bell and offered to sell it to him for $1 million. He rejected the offer. Vinod Khosla, one of Excite's venture capitalists, talked the duo down to $750,000, but Bell still rejected it.[34]

Google's initial public offering (IPO) took place five years later, on August 19, 2004. At that time Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt agreed to work together at Google for 20 years, until the year 2024.[35]

At IPO, the company offered 19,605,052 shares at a price of $85 per share.[36][37] Shares were sold in an online auction format using a system built by Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse, underwriters for the deal.[38][39] The sale of $1.67 bn (billion) gave Google a market capitalization of more than $23bn.[40] By January 2014, its market capitalization had grown to $397bn.[41] The vast majority of the 271 million shares remained under the control of Google, and many Google employees became instant paper millionaires. Yahoo!, a competitor of Google, also benefitted because it owned 8.4 million shares of Google before the IPO took place.[42]

There were concerns that Google's IPO would lead to changes in company culture. Reasons ranged from shareholder pressure for employee benefit reductions to the fact that many company executives would become instant paper millionaires.[43] As a reply to this concern, co-founders Brin and Page promised in a report to potential investors that the IPO would not change the company's culture.[44] In 2005, articles in The New York Times[45] and other sources began suggesting that Google had lost its anti-corporate, no evil philosophy.[46][47][48] In an effort to maintain the company's unique culture, Google designated a Chief Culture Officer, who also serves as the Director of Human Resources. The purpose of the Chief Culture Officer is to develop and maintain the culture and work on ways to keep true to the core values that the company was founded on: a flat organization with a collaborative environment.[49] Google has also faced allegations of sexism and ageism from former employees.[50][51] In 2013, a class action against several Silicon Valley companies, including Google, was filed for alleged "no cold call" agreements which restrained the recruitment of high-tech employees.[52]

The stock performed well after the IPO, with shares hitting $350 for the first time on October 31, 2007,[53] primarily because of strong sales and earnings in the online advertising market.[54] The surge in stock price was fueled mainly by individual investors, as opposed to large institutional investors and mutual funds.[54] GOOG shares split into GOOG class C shares and GOOGL class A shares.[55] The company is listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange under the ticker symbols GOOGL and GOOG, and on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol GGQ1. These ticker symbols now refer to Alphabet Inc., Google's holding company, since the fourth quarter of 2015.[update][56]

Growth

In March 1999, the company moved its offices to Palo Alto, California,[57] which is home to several prominent Silicon Valley technology start-ups.[58] The next year, Google began selling advertisements associated with search keywords against Page and Brin's initial opposition toward an advertising-funded search engine.[59][14] To maintain an uncluttered page design, advertisements were solely text-based.[60]

This model of selling keyword advertising was first pioneered by Goto.com, an Idealab spin-off created by Bill Gross.[61][62] When the company changed names to Overture Services, it sued Google over alleged infringements of the company's pay-per-click and bidding patents. Overture Services would later be bought by Yahoo! and renamed Yahoo! Search Marketing. The case was then settled out of court; Google agreed to issue shares of common stock to Yahoo! in exchange for a perpetual license.[63]

In June 2000, it was announced that Google would become the default search engine provider for Yahoo!, one of the most popular websites at the time, replacing Inktomi.[64][65]

In 2001, Google received a patent for its PageRank mechanism.[66] The patent was officially assigned to Stanford University and lists Lawrence Page as the inventor. In 2003, after outgrowing two other locations, the company leased an office complex from Silicon Graphics, at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway in Mountain View, California.[67] The complex became known as the Googleplex, a play on the word googolplex, the number one followed by a googol zeroes. The Googleplex interiors were designed by Clive Wilkinson Architects. Three years later, Google bought the property from SGI for $319 million.[68] By that time, the name "Google" had found its way into everyday language, causing the verb "google" to be added to the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary, denoted as: "to use the Google search engine to obtain information on the Internet".[69][70] The first use of "Google" as a verb in pop culture happened on the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, in 2002.[71] Additionally, in 2001 Google's Investors felt the need to have a strong internal management, and they agreed to hire Eric Schmidt as the Chairman and CEO of Google [72]

In 2005, The Washington Post reported on a 700 percent increase in third-quarter profit for Google, largely thanks to large companies shifting their advertising strategies from newspapers, magazines, and television to the Internet.[73] In January 2008, all the data that passed through Google's MapReduce software component had an aggregated size of 20 petabytes per day.[74][75][76] In 2009, a CNN report about top political searches of 2009 noted that "more than a billion searches" are being typed into Google on a daily basis.[77] In May 2011, the number of monthly unique visitors to Google surpassed one billion for the first time, an 8.4 percent increase from May 2010 (931 million).[78]

By 2011, Google was handling approximately 3 billion searches per day, to handle this workload, Google built 11 datacenters around the world with some several thousand servers in each. These datacenters allowed Google to handle the ever changing workload more efficiently. [79]

The year 2012 was the first time that Google generated $50 billion in annual revenue, generating $38 billion the previous year. In January 2013, then-CEO Larry Page commented, "We ended 2012 with a strong quarter ... Revenues were up 36% year-on-year, and 8% quarter-on-quarter. And we hit $50 billion in revenues for the first time last year – not a bad achievement in just a decade and a half."[80]

In November 2018, Google announced its plan to expand its New York City office to a capacity of 12,000 employees.[81]

2013 onward

Google announced the launch of a new company, called Calico, on September 19, 2013, to be led by Apple, Inc. chairman Arthur Levinson. In the official public statement, Page explained that the "health and well-being" company would focus on "the challenge of ageing and associated diseases".[82]

Google celebrated its 15-year anniversary on September 27, 2013, and in 2016 it celebrated its 18th birthday with an animated version of its logo (a "Google Doodle"),[83] although it has used other dates for its official birthday.[84] The reason for the choice of September 27 remains unclear, and a dispute with rival search engine Yahoo! Search in 2005 has been suggested as the cause.[85][86]

The Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) was launched in October 2013; Google is part of the coalition of public and private organizations that also includes Facebook, Intel, and Microsoft. Led by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the A4AI seeks to make Internet access more affordable so that access is broadened in the developing world, where only 31% of people are online. Google will help to decrease Internet access prices so they fall below the UN Broadband Commission's worldwide target of 5% of monthly income.[87]

The corporation's consolidated revenue for the third quarter of 2013 was reported in mid-October 2013 as $14.89 billion, a 12 percent increase compared to the previous quarter.[88] Google's Internet business was responsible for $10.8 billion of this total, with an increase in the number of users' clicks on advertisements.[89]

According to Interbrand's annual Best Global Brands report, Google has been the second most valuable brand in the world (behind Apple Inc.) in 2013,[90] 2014,[91] 2015,[92] and 2016, with a valuation of $133 billion.[93]

In September 2015, Google engineering manager Rachel Potvin revealed details about Google's software code at an engineering conference. She revealed that the entire Google codebase, which spans every single service it develops, consists of over 2 billion lines of code. All that code is stored in a code repository available to all 25,000 Google engineers, and the code is regularly copied and updated on 10 Google data centers. To keep control, Potvin said Google has built its own "version control system", called "Piper", and that "when you start a new project, you have a wealth of libraries already available to you. Almost everything has already been done." Engineers can make a single code change and deploy it on all services at the same time. The only major exceptions are that the PageRank search results algorithm is stored separately with only specific employee access, and the code for the Android operating system and the Google Chrome browser are also stored separately, as they don't run on the Internet. The "Piper" system spans 85 TB of data. Google engineers make 25,000 changes to the code each day and on a weekly basis change approximately 15 million lines of code across 250,000 files. With that much code, automated bots have to help. Potvin reported, "You need to make a concerted effort to maintain code health. And this is not just humans maintaining code health, but robots too.” Bots aren't writing code, but generating a lot of the data and configuration files needed to run the company's software. "Not only is the size of the repository increasing," Potvin explained, "but the rate of change is also increasing. This is an exponential curve."[94][95]

As of October 2016,[update] Google operates 70 offices in more than 40 countries.[96] Alexa, a company that monitors commercial web traffic, lists Google.com as the most visited website in the world.[9] Several other Google services also figure in the top 100 most visited websites, including YouTube[97] and Blogger.[98]

Acquisitions and partnerships

2000–2009

In 2001, Google acquired Deja News, the operators of a large archive of materials from Usenet.[99][100] Google rebranded the archive as Google Groups, and by the end of the year, it had expanded the history back to 1981.[101][102]

In April 2003, Google acquired Applied Semantics, a company specializing in making software applications for the online advertising space.[103][104] The AdSense contextual advertising technology developed by Applied Semantics was adopted into Google's advertising efforts.[105][102]

In 2004, Google acquired Keyhole, Inc.[106] Keyhole's eponymous product was later renamed Google Earth.

In April 2005, Google acquired Urchin Software, using their Urchin on Demand product (along with ideas from Adaptive Path's Measure Map) to create Google Analytics in 2006.

In October 2006, Google announced that it had acquired the video-sharing site YouTube for $1.65 billion in Google stock,[107][108] and the deal was finalized on November 13, 2006.[109][110]

On April 13, 2007, Google reached an agreement to acquire DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, transferring to Google valuable relationships that DoubleClick had with Web publishers and advertising agencies.[111] The deal was approved despite anti-trust concerns raised by competitors Microsoft and AT&T.[112]

In addition to the many companies Google has purchased, the firm has partnered with other organizations for research, advertising, and other activities. In 2005, Google partnered with NASA Ames Research Center to build 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) of offices.[113]

In 2005 Google partnered with AOL[114] to enhance each other's video search services. In 2006 Google and Fox Interactive Media of News Corporation entered into a $900 million agreement to provide search and advertising on the then-popular social networking site MySpace.[115]

In 2007, Google began sponsoring NORAD Tracks Santa, displacing the former sponsor AOL. NORAD Tracks Santa purports to follow Santa Claus' progress on Christmas Eve,[116] using Google Earth to "track Santa" in 3-D for the first time.[117][118]

In 2008, Google developed a partnership with GeoEye to launch a satellite providing Google with high-resolution (0.41 m monochrome, 1.65 m color) imagery for Google Earth. The satellite was launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base on September 6, 2008.[119] Google also announced in 2008 that it was hosting an archive of Life Magazine's photographs.[120][121]

2010–present

In 2010, Google Energy made its first investment in a renewable energy project, putting $38.8 million into two wind farms in North Dakota. The company announced the two locations will generate 169.5 megawatts of power, enough to supply 55,000 homes. The farms, which were developed by NextEra Energy Resources, will reduce fossil fuel use in the region and return profits. NextEra Energy Resources sold Google a twenty-percent stake in the project to get funding for its development.[122] In February 2010, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission FERC granted Google an authorization to buy and sell energy at market rates.[123] The order specifically states that Google Energy—a subsidiary of Google—holds the rights "for the sale of energy, capacity, and ancillary services at market-based rates", but acknowledges that neither Google Energy nor its affiliates "own or control any generation or transmission" facilities.[124] The corporation exercised this authorization in September 2013 when it announced it would purchase all the electricity produced by the not-yet-built 240-megawatt Happy Hereford wind farm.[125]

Also in 2010, Google purchased Global IP Solutions, a Norway-based company that provides web-based teleconferencing and other related services. This acquisition enabled Google to add telephone-style services to its list of products.[126] On May 27, 2010, Google announced it had also closed the acquisition of the mobile ad network AdMob. This occurred days after the Federal Trade Commission closed its investigation into the purchase.[127] Google acquired the company for an undisclosed amount.[128] In July 2010, Google signed an agreement with an Iowa wind farm to buy 114 megawatts of energy for 20 years.[129]

On April 4, 2011, The Globe and Mail reported that Google bid $900 million for 6000 Nortel Networks patents.[130]

On August 15, 2011, Google made its largest-ever acquisition to date when it announced that it would acquire Motorola Mobility for $12.5 billion[131][132] subject to approval from regulators in the United States and Europe. In a post on Google's blog, Google Chief Executive and co-founder Larry Page revealed that the acquisition was a strategic move to strengthen Google's patent portfolio. The company's Android operating system has come under fire in an industry-wide patent battle, as Apple and Microsoft have sued Android device makers such as HTC, Samsung, and Motorola.[133] The merger was completed on May 22, 2012, after the approval of China.[134]

This purchase was made in part to help Google gain Motorola's considerable patent portfolio on mobile phones and wireless technologies, to help protect Google in its ongoing patent disputes with other companies,[135] mainly Apple and Microsoft,[133] and to allow it to continue to freely offer Android.[136] After the acquisition closed, Google began to restructure the Motorola business to fit Google's strategy. On August 13, 2012, Google announced plans to lay off 4000 Motorola Mobility employees.[137] On December 10, 2012, Google sold the manufacturing operations of Motorola Mobility to Flextronics for $75 million.[138] As a part of the agreement, Flextronics will manufacture undisclosed Android and other mobile devices.[139] On December 19, 2012, Google sold the Motorola Home business division of Motorola Mobility to Arris Group for $2.35 billion in a cash-and-stock transaction. As a part of this deal, Google acquired a 15.7% stake in Arris Group valued at $300 million.[140][141]

In June 2013, Google acquired Waze, a $966 million deal.[142] While Waze would remain an independent entity, its social features, such as its crowdsourced location platform, were reportedly valuable integrations between Waze and Google Maps, Google's own mapping service.[143]

On January 26, 2014, Google announced it had agreed to acquire DeepMind Technologies, a privately held artificial intelligence company from London. DeepMind describes itself as having the ability to combine the best techniques from machine learning and systems neuroscience to build general-purpose learning algorithms. DeepMind's first commercial applications were used in simulations, e-commerce and games. As of December 2013,[update] it was reported that DeepMind had roughly 75 employees.[144] Technology news website Recode reported that the company was purchased for $400 million though it was not disclosed where the information came from. A Google spokesman would not comment of the price.[145][146] The purchase of DeepMind aids in Google's recent growth in the artificial intelligence and robotics community.[147]

On January 29, 2014, Google announced that it would divest Motorola Mobility to Lenovo for $2.91 billion, a fraction of the original $12.5 billion price paid by Google to acquire the company. Google retained all but 2000 of Motorola's patents and entered into cross-licensing deals.[148]

On September 21, 2017, HTC announced a "cooperation agreement" in which it would sell non-exclusive rights to certain intellectual property, as well as smartphone talent, to Google for $1.1 billion.[149][150][151]

On December 6, 2017, Google made its first investment in India and picked up a significant minority stake in hyper-local concierge and delivery player Dunzo.[152] The Benguluru-based startup received $12 million investment in Google's series B funding round.[153]

On March 29, 2018, Google led a Series C funding round into online-to-offline fashion e-commerce start-up Fynd.[154] It was its second direct investment in India with an undisclosed amount.[155][156] In this way, Google is also looking to build an ecosystem in India across high-frequency hyper-local transactions as well as in the healthcare, financial services, and education sectors.

On August 23, 2018, Google deleted 39 YouTube accounts, 13 Google+ accounts and 6 blogs on Blogger due to their engagement in politically motivated phishing, the deleted accounts were found to be tied with Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB).[157][158][159]

On March 19, 2019, Google announced that it would enter the Video Game market, releasing the Google Stadia. Stadia will be a cloud gaming console, dubbed 'The Netflix of gaming'. Stadia will be released in 2019

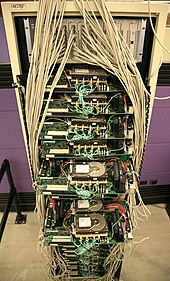

Google data centers

Google data centers are located in North and South America, Asia, Europe.[160]

Traditionally, Google relied on parallel computing on commodity hardware[161] like mainstream x86 computers similar to home PCs[162] to keep costs per query low.[163] In 2005, it started developing its own designs, which were only revealed in 2009.[163]

In October 2013, The Washington Post reported that the U.S. National Security Agency intercepted communications between Google's data centers, as part of a program named MUSCULAR.[164][165] This wiretapping was made possible because Google did not encrypt data passed inside its own network.[166] Google began encrypting data sent between data centers in 2013.[167]

Google's most efficient data center runs at 35 °C (95 °F) using only fresh air cooling, requiring no electrically powered air conditioning; the servers run so hot that humans cannot go near them for extended periods.[168]

An August 2011 report estimated that Google had about 900,000 servers in their data centers, based on energy usage. The report does state that "Google never says how many servers are running in its data centers."[169]

In December 2016, Google announced that—starting in 2017—it will power all of its data centers, as well as all of its offices, from 100% renewable energy. The commitment will make Google "the world's largest corporate buyer of renewable power, with commitments reaching 2.6 gigawatts (2,600 megawatts) of wind and solar energy". Google also stated that it does not count that as its final goal; it says that "since the wind doesn't blow 24 hours a day, we'll also broaden our purchases to a variety of energy sources that can enable renewable power, every hour of every day". Additionally, the project will "help support communities" around the world, as the purchase commitments will "result in infrastructure investments of more than $3.5 billion globally", and will "generate tens of millions of dollars per year in revenue to local property owners, and tens of millions more to local and national governments in tax revenue".[170][171][172]

Alphabet

On August 10, 2015, Google announced plans to reorganize its various interests as a conglomerate called Alphabet. Google became Alphabet's leading subsidiary, and will continue to be the umbrella company for Alphabet's Internet interests. Upon completion of the restructure, Sundar Pichai became CEO of Google, replacing Larry Page, who became CEO of Alphabet.[173][174][175]

On September 1, 2017, Google Inc. announced its plans of restructuring as a limited liability company, Google LLC, as a wholly owned subsidiary of XXVI Holdings Inc., which is formed as a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. to hold the equity of its other subsidiaries, including Google LLC and other bets.[176]

Products and services

Advertising

As per its 2017 Annual report, Google generates most of its revenues from advertising. This includes sales of apps, purchases made in-app, digital content products on google and YouTube, android and licensing and service fees, including fees received for Google Cloud offerings. 46% of this was from clicks (cost per clicks), amounting to US$109,652 million in 2017. This includes three principal methods, namely AdMob, AdSense (such as AdSense for Content, AdSense for Search, etc.) and DoubleClick AdExchange.[177]

For the 2006 fiscal year, the company reported $10.492 billion in total advertising revenues and only $112 million in licensing and other revenues.[178] In 2011, 96% of Google's revenue was derived from its advertising programs.[179] In addition to its own algorithms for understanding search requests, Google uses technology from the company DoubleClick, to project user interest and target advertising to the search context and the user history.[180][181]

In 2007, Google launched "AdSense for Mobile", taking advantage of the emerging mobile advertising market.[182]

Google Analytics allows website owners to track where and how people use their website, for example by examining click rates for all the links on a page.[183] Google advertisements can be placed on third-party websites in a two-part program. Google's AdWords allows advertisers to display their advertisements in the Google content network, through a cost-per-click scheme.[184] The sister service, Google AdSense, allows website owners to display these advertisements on their website and earn money every time ads are clicked.[185]

One of the criticisms of this program is the possibility of click fraud, which occurs when a person or automated script clicks on advertisements without being interested in the product, causing the advertiser to pay money to Google unduly. Industry reports in 2006 claimed that approximately 14 to 20 percent of clicks were fraudulent or invalid.[186]

In February 2003, Google stopped showing the advertisements of Oceana, a non-profit organization protesting a major cruise ship's sewage treatment practices. Google cited its editorial policy at the time, stating "Google does not accept advertising if the ad or site advocates against other individuals, groups, or organizations."[187] In June 2008, Google reached an advertising agreement with Yahoo!, which would have allowed Yahoo! to feature Google advertisements on its web pages. The alliance between the two companies was never completely realized because of antitrust concerns by the U.S. Department of Justice. As a result, Google pulled out of the deal in November 2008.[188][189]

In July 2016, Google started rejecting all flash-based adverts replacing them by HTML5. Google's plan was to go “100% HTML5” beginning on January 2, 2017.[190]

Search engine

According to comScore market research from November 2009, Google Search is the dominant search engine in the United States market, with a market share of 65.6%.[191] Google indexes billions of web pages to allow users to search for the information they desire through the use of keywords and operators.[192]

In 2003, The New York Times complained about Google's indexing, claiming that Google's caching of content on its site infringed its copyright for the content.[193] In both Field v. Google and Parker v. Google, the United States District Court of Nevada ruled in favor of Google.[194][195] The publication 2600: The Hacker Quarterly has compiled a list of words that google's new instant search feature will not search.[196]

Google also hosts Google Books. The company began scanning books and uploading limited previews, and full books were allowed, into its new book search engine. The Authors Guild, a group that represents 8,000 U.S. authors, filed a class action suit in a New York City federal court against Google in 2005 over this service. Google replied that it is in compliance with all existing and historical applications of copyright laws regarding books.[197] Google eventually reached a revised settlement in 2009 to limit its scans to books from the U.S., the UK, Australia, and Canada.[198] Furthermore, the Paris Civil Court ruled against Google in late 2009, asking it to remove the works of La Martinière (Éditions du Seuil) from its database.[199] In competition with Amazon.com, Google sells digital versions of new books.[200]

On July 21, 2010, in response to Bing, Google updated its image search to display a streaming sequence of thumbnails that enlarge when pointed at. Although web searches still appear in a batch per page format, on July 23, 2010, dictionary definitions for certain English words began appearing above the linked results for web searches.[201]

The "Hummingbird" update to the Google search engine was announced in September 2013. The update was introduced over the month prior to the announcement and allows users ask the search engine a question in natural language rather than entering keywords into the search box.[202]

In August 2016, Google announced two major changes to its mobile search results. The first change removes the "mobile-friendly" label that highlighted easy to read pages from its mobile search results page. For the second change, the company—starting on January 10, 2017—will punish mobile pages that show intrusive interstitial advertisements when a user first opens a page. Such pages will also rank lower in Google search results.[203]

In May 2017, Google enabled a new "Personal" tab in Google Search, letting users search for content in their Google accounts' various services, including email messages from Gmail and photos from Google Photos.[204][205]

Enterprise services

G Suite is a monthly subscription offering for organizations and businesses to get access to a collection of Google's services, including Gmail, Google Drive and Google Docs, Google Sheets and Google Slides, with additional administrative tools, unique domain names, and 24/7 support.[206]

Google Search Appliance was launched in February 2002, targeted toward providing search technology for larger organizations.[14] Google launched the Mini three years later, which was targeted at smaller organizations. Late in 2006, Google began to sell Custom Search Business Edition, providing customers with an advertising-free window into Google.com's index. The service was renamed Google Site Search in 2008.[207] Site Search customers were notified by email in late March 2017 that no new licenses for Site Search would be sold after April 1, 2017, but that customer and technical support would be provided for the duration of existing license agreements.[208][209]

On March 15, 2016, Google announced the introduction of Google Analytics 360 Suite, "a set of integrated data and marketing analytics products, designed specifically for the needs of enterprise-class marketers" which can be integrated with BigQuery on the Google Cloud Platform. Among other things, the suite is designed to help "enterprise class marketers" "see the complete customer journey", generate "useful insights", and "deliver engaging experiences to the right people".[210] Jack Marshall of The Wall Street Journal wrote that the suite competes with existing marketing cloud offerings by companies including Adobe, Oracle, Salesforce, and IBM.[211]

Business incubator

On September 24, 2012,[212] Google launched Google for Entrepreneurs, a largely not-for-profit business incubator providing startups with co-working spaces known as Campuses, with assistance to startup founders that may include workshops, conferences, and mentorships.[213] Presently, there are 7 Campus locations in Berlin, London, Madrid, Seoul, São Paulo, Tel Aviv, and Warsaw.

Consumer services

Web-based services

Google offers Gmail, and the newer variant Inbox[214] for email,[215] (Inbox has plans to shut down by the end of March 2019) [216] Google Calendar for time-management and scheduling,[217] Google Maps for mapping, navigation and satellite imagery,[218] Google Drive for cloud storage of files,[219] Google Docs, Sheets and Slides for productivity,[219] Google Photos for photo storage and sharing,[220] Google Keep for note-taking,[221] Google Translate for language translation,[222] YouTube for video viewing and sharing,[223] Google My Business for managing public business information,[224] and Google+ (which will be closing down on April 2, 2019),[225][226] Allo, and Duo for social interaction.[227] Allo has officially shut down as of March 12, 2019. [228][229][230]

Software

Google develops the Android mobile operating system,[231] as well as its smartwatch,[232] television,[233] car,[234] and Internet of things-enabled smart devices variations.[235]

It also develops the Google Chrome web browser,[236] and Chrome OS, an operating system based on Chrome.[237]

Hardware

In January 2010, Google released Nexus One, the first Android phone under its own, "Nexus", brand.[238] It spawned a number of phones and tablets under the "Nexus" branding[239] until its eventual discontinuation in 2016, replaced by a new brand called, Pixel.[240]

In 2011, the Chromebook was introduced, described as a "new kind of computer" running Chrome OS.[241]

In July 2013, Google introduced the Chromecast dongle, that allows users to stream content from their smartphones to televisions.[242][243]

In June 2014, Google announced Google Cardboard, a simple cardboard viewer that lets user place their smartphone in a special front compartment to view virtual reality (VR) media.[244][245]

In April 2016, Recode reported that Google had hired Rick Osterloh, Motorola Mobility's former President, to head Google's new hardware division.[246] In October 2016, Osterloh stated that "a lot of the innovation that we want to do now ends up requiring controlling the end-to-end user experience",[240] and Google announced several hardware platforms:

- The Pixel and Pixel XL smartphones with the Google Assistant, a next-generation contextual voice assistant, built-in.[247]

- Google Home, an Amazon Echo-like voice assistant placed in the house that can answer voice queries, play music, find information from apps (calendar, weather etc.), and control third-party smart home appliances (users can tell it to turn on the lights, for example). The Google Home line also includes variants such as the Google Home Hub, Google Home Mini, and Google Home Max[248]

- Daydream View virtual reality headset that lets Android users with compatible Daydream-ready smartphones put their phones in the headset and enjoy VR content.[249]

- Google Wifi, a connected set of Wi-Fi routers to simplify and extend coverage of home Wi-Fi.[250]

Internet services

In February 2010, Google announced the Google Fiber project, with experimental plans to build an ultra-high-speed broadband network for 50,000 to 500,000 customers in one or more American cities.[251][252] Following Google's corporate restructure to make Alphabet Inc. its parent company, Google Fiber was moved to Alphabet's Access division.[253][254]

In April 2015, Google announced Project Fi, a mobile virtual network operator, that combines Wi-Fi and cellular networks from different telecommunication providers in an effort to enable seamless connectivity and fast Internet signal.[255][256][257]

In September 2016, Google began its Google Station initiative, a project for public Wi-Fi at railway stations in India. Caesar Sengupta, VP for Google's next billion users, told The Verge that 15,000 people get online for the first time thanks to Google Station and that 3.5 million people use the service every month. The expansion meant that Google was looking for partners around the world to further develop the initiative, which promised "high-quality, secure, easily accessible Wi-Fi".[258] By December, Google Station had been deployed at 100 railway stations,[259] and in February, Google announced its intention to expand beyond railway stations, with a plan to bring citywide Wi-Fi to Pune.[260][261]

As of October 2018[update], Orange has teamed up with Google in order to create a transatlantic undersea cable to share data between the United States and France at faster speeds. Planned to begin operation in 2020, the cable is purported to transfer information at rates “more than 30 terabits per second, per [fibre] pair”. The cable will span approximately 6600 kilometers in length.[262]

Other products

Google launched its Google News service in 2002, an automated service which summarizes news articles from various websites.[263] In March 2005, Agence France Presse (AFP) sued Google for copyright infringement in federal court in the District of Columbia, a case which Google settled for an undisclosed amount in a pact that included a license of the full text of AFP articles for use on Google News.[264]

In May 2011, Google announced Google Wallet, a mobile application for wireless payments.[265]

In 2013, Google launched Google Shopping Express, a delivery service initially available only in San Francisco and Silicon Valley.[266]

Google Alerts is a content change detection and notification service, offered by the search engine company Google. The service sends emails to the user when it finds new results—such as web pages, newspaper articles, or blogs—that match the user's search term.[267][268][269]

In July 2015 Google released DeepDream, an image recognition software capable of creating psychedelic images using a convolutional neural network.[270][271][272]

Google introduced its Family Link service in March 2017, letting parents buy Android Nougat-based Android devices for kids under 13 years of age and create a Google account through the app, with the parents controlling the apps installed, monitor the time spent using the device, and setting a "Bedtime" feature that remotely locks the device.[273][274][275]

In April 2017, Google launched AutoDraw, a web-based tool using artificial intelligence and machine learning to recognize users' drawings and replace scribbles with related stock images that have been created by professional artists.[276][277][278] The tool is built using the same technology as QuickDraw, an experimental game from Google's Creative Lab where users were tasked with drawing objects that algorithms would recognize within 20 seconds.[279]

In May 2017, Google added "Family Groups" to several of its services. The feature, which lets users create a group consisting of their family members' individual Google accounts, lets users add their "Family Group" as a collaborator to shared albums in Google Photos, shared notes in Google Keep, and common events in Google Calendar. At announcement, the feature is limited to Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, Spain, United Kingdom and United States.[280][281]

In March 2019, Google unveiled a cloud gaming service named Stadia.[282]

APIs

Google APIs are a set of application programming interfaces (APIs) developed by Google which allow communication with Google Services and their integration to other services. Examples of these include Search, Gmail, Translate or Google Maps. Third-party apps can use these APIs to take advantage of or extend the functionality of the existing services.

Other websites

Google Developers is Google's site for software development tools, APIs, and technical resources. The site contains documentation on using Google developer tools and APIs—including discussion groups and blogs for developers using Google's developer products.

Google Labs was a page created by Google to demonstrate and test new projects.

Google owns the top-level domain 1e100.net which is used for some servers within Google's network. The name is a reference to the scientific E notation representation for 1 googol, 1E100 = 1 × 10100.[283]

In March 2017, Google launched a new website, opensource.google.com, to publish its internal documentation for Google Open Source projects.[284][285]

In June 2017, Google launched "We Wear Culture", a searchable archive of 3,000 years of global fashion. The archive, a result of collaboration between Google and over 180 museums, schools, fashion institutes, and other organizations, also offers curated exhibits of specific fashion topics and their impact on society.[286][287]

Corporate affairs and culture

On Fortune magazine's list of the best companies to work for, Google ranked first in 2007, 2008 and 2012,[288][289][290] and fourth in 2009 and 2010.[291][292] Google was also nominated in 2010 to be the world's most attractive employer to graduating students in the Universum Communications talent attraction index.[293] Google's corporate philosophy includes principles such as "you can make money without doing evil," "you can be serious without a suit," and "work should be challenging and the challenge should be fun."[294]

Innovation Time Off policy

As a motivation technique, Google uses a policy known as Innovation Time Off, where Google engineers are encouraged to spend 20% of their work time on projects that interest them. Some of Google's services, such as Gmail, Google News, Orkut, and AdSense originated from these independent endeavors.[295] In a talk at Stanford University, Marissa Mayer, Google's Vice-President of Search Products and User Experience until July 2012, showed that half of all new product launches in the second half of 2005 had originated from the Innovation Time Off.[296]

The New York Times exposé (2018)

On 25 October 2018, The New York Times published the exposé, "How Google Protected Andy Rubin, the ‘Father of Android’". The company subsequently announced that "48 employees have been fired over the last two years" for sexual misconduct.[297] A week after the article appeared, Google X (renamed X Development LLC in 2015) executive Rich DeVaul resigned pursuant to a complaint of sexual harassment.[298]

Employees

As of December 2018,[update] Google has 98,771 employees.[4] Google's 2017[update] diversity report states that 31 percent of its workforce are women and 69 percent are men, with the ethnicity of its workforce being predominantly white (56%) and Asian (35%).[300] Within tech roles, however, 20 percent were women; and 25 percent of leadership roles were held by women.[300] The report also announced that Intel's former vice-president, CDO, and CHRO Danielle Brown would be joining Google as its new Vice-President of Diversity.[300] A March 2013 report was presented at EclipseCon2013 which detailed that Google had over 10,000 developers based in more than 40 offices.[301][needs update]

Google's employees are hired based on a hierarchical system. Employees are split into six hierarchies based on experience and can range "from entry-level data center workers at level one to managers and experienced engineers at level six."[302]

Following the company's IPO in 2004, founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page and CEO Eric Schmidt requested that their base salary be cut to $1. Subsequent offers by the company to increase their salaries were turned down, primarily because their main compensation continues to come from owning stock in Google. Before 2004, Schmidt made $250,000 per year, and Page and Brin each received an annual salary of $150,000.[303]

In March 2008, Sheryl Sandberg, then vice-president of global online sales and operations, began her position as chief operating officer of Facebook.[304][305] In 2009, early employee Tim Armstrong left to become CEO of AOL. In July 2012, Google's first female engineer, Marissa Mayer, left Google to become Yahoo!'s CEO.[306]

In January 2017, Google employees donated over $2 million to a crisis fund in support of refugees; the company matched the donation with an additional $2 million. Employees then organized a global workplace walk-out, aided by the hashtag #GooglersUnite, to protest U.S. President Donald Trump's Muslim travel ban.[307][308]

In late 2017, former Intel executive Diane Bryant became Chief Operating Officer of Google Cloud.[309]

On 1 November 2018, Google employees staged a global walk-out to protest the company's handling of sexual harassment complaints, including the golden parachute exit of former executive Andy Rubin;[310] more than 20,000 employees and contractors participated.[311] CEO Sundar Pichai was reported to be in support of the protests.[312]

Office locations and headquarters

Mountain View

Google's headquarters in Mountain View, California is referred to as "the Googleplex", a play on words on the number googolplex and the headquarters itself being a complex of buildings. The lobby is decorated with a piano, lava lamps, old server clusters, and a projection of search queries on the wall. The hallways are full of exercise balls and bicycles. Many employees have access to the corporate recreation center. Recreational amenities are scattered throughout the campus and include a workout room with weights and rowing machines, locker rooms, washers and dryers, a massage room, assorted video games, table football, a baby grand piano, a billiard table, and ping pong. In addition to the recreation room, there are snack rooms stocked with various foods and drinks, with special emphasis placed on nutrition.[313] Free food is available to employees 24/7, with the offerings provided by paid vending machines prorated based on and favoring those of better nutritional value.[314]

Google's extensive amenities are not available to all of its workers. Temporary workers such as book scanners do not have access to shuttles, Google cafes, or other perks.[315]

New York City

In 2006, Google moved into about 300,000 square feet (27,900 m2) of office space in New York City, at 111 Eighth Avenue in Manhattan. The office was designed and built specially for Google, and houses its largest advertising sales team, which has been instrumental in securing large partnerships.[316] The New York headquarters includes a game room, micro-kitchens, and a video game area.[317] In 2010, Google bought the building housing the headquarter, in a deal that valued the property at around $1.9 billion, the biggest for a single building in the United States that year.[318][319] In February 2012, Google moved additional employees to the New York City campus, with a total of around 2,750 employees.[320]

Google's New York City location continued to expand in 2018. In March of that year, Google's parent company Alphabet bought Chelsea Market building for $2.4 billion nearby its current New York HQ. The sale is touted as one of the most expensive real estate transactions for a single building in the history of New York.[321][322][323][324] The same December, it was announced that a $1 billion, 1,700,000-square-foot (160,000 m2) headquarters for Google would be built in Manhattan's Hudson Square neighborhood.[325][326] Called Google Hudson Square, the new campus is projected to more than double the number of Google employees working in New York City.[327]

Other U.S. cities

By late 2006, Google established a new headquarters for its AdWords division in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[328] In November 2006, Google opened offices on Carnegie Mellon's campus in Pittsburgh, focusing on shopping-related advertisement coding and smartphone applications and programs.[329][330] Other office locations in the U.S. include Atlanta, Georgia; Austin, Texas; Boulder, Colorado; Cambridge, Massachusetts; San Francisco, California; Seattle, Washington; Kirkland, Washington; Birmingham, Michigan; Reston, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.[331]

In October 2006, the company announced plans to install thousands of solar panels to provide up to 1.6 megawatts of electricity, enough to satisfy approximately 30% of the campus' energy needs.[332] The system will be the largest solar power system constructed on a U.S. corporate campus and one of the largest on any corporate site in the world.[332] In addition, Google announced in 2009 that it was deploying herds of goats to keep grassland around the Googleplex short, helping to prevent the threat from seasonal bush fires while also reducing the carbon footprint of mowing the extensive grounds.[333][334] The idea of trimming lawns using goats originated from Bob Widlar, an engineer who worked for National Semiconductor.[335] In 2008, Google faced accusations in Harper's Magazine of being an "energy glutton". The company was accused of employing its "Don't be evil" motto and its public energy-saving campaigns to cover up or make up for the massive amounts of energy its servers require.[336]

International locations

Internationally, Google has over 78 offices in more than 50 countries.[337] It also has product research and development operations in cities around the world, namely Sydney (birthplace location of Google Maps)[338] and London (part of Android development).[339]

In November 2013, Google announced plans for a new London headquarter, a notable 1 million square foot office able to accommodate 4,500 employees. Recognized as one of the biggest ever commercial property acquisitions at the time of the deal's announcement in January,[340] Google submitted plans for the new headquarter to the Camden Council in June 2017. The new building, if approved, will feature a rooftop garden with a running track, giant moving blinds, a swimming pool, and a multi-use games area for sports.[341][342]

In May 2015, Google announced its intention to create its own campus in Hyderabad, India. The new campus, reported to be the company's largest outside the United States, will accommodate 13,000 employees.[343][344]

Doodles

Since 1998,[update] Google has been designing special, temporary alternate logos to place on their homepage intended to celebrate holidays, events, achievements and people. The first Google Doodle was in honor of the Burning Man Festival of 1998.[345][346] The doodle was designed by Larry Page and Sergey Brin to notify users of their absence in case the servers crashed. Subsequent Google Doodles were designed by an outside contractor, until Larry and Sergey asked then-intern Dennis Hwang to design a logo for Bastille Day in 2000. From that point onward, Doodles have been organized and created by a team of employees termed "Doodlers".[347]

Easter eggs and April Fools' Day jokes

Google has a tradition of creating April Fools' Day jokes. On April 1, 2000, Google MentalPlex allegedly featured the use of mental power to search the web.[348] In 2007, Google announced a free Internet service called TiSP, or Toilet Internet Service Provider, where one obtained a connection by flushing one end of a fiber-optic cable down their toilet.[349] Also in 2007, Google's Gmail page displayed an announcement for Gmail Paper, allowing users to have email messages printed and shipped to them.[350] In 2008, Google announced Gmail Custom time where users could change the time that the email was sent.[351]

In 2010, Google changed its company name to Topeka in honor of Topeka, Kansas, whose mayor changed the city's name to Google for a short amount of time in an attempt to sway Google's decision in its new Google Fiber Project.[352][353] In 2011, Google announced Gmail Motion, an interactive way of controlling Gmail and the computer with body movements via the user's webcam.[354]

Google's services contain easter eggs, such as the Swedish Chef's "Bork bork bork," Pig Latin, "Hacker" or leetspeak, Elmer Fudd, Pirate, and Klingon as language selections for its search engine.[355] The search engine calculator provides the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything from Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.[356] When searching the word "recursion", the spell-checker's result for the properly spelled word is exactly the same word, creating a recursive link.[357]

When searching for the word "anagram," meaning a rearrangement of letters from one word to form other valid words, Google's suggestion feature displays "Did you mean: nag a ram?"[358] During FIFA World Cup 2010, search queries including "World Cup" and "FIFA" caused the "Goooo...gle" page indicator at the bottom of every result page to read "Goooo...al!" instead.[359]

Philanthropy

In 2004, Google formed the not-for-profit philanthropic Google.org, with a start-up fund of $1 billion.[360] The mission of the organization is to create awareness about climate change, global public health, and global poverty. One of its first projects was to develop a viable plug-in hybrid electric vehicle that can attain 100 miles per gallon. Google hired Larry Brilliant as the program's executive director in 2004[361] and Megan Smith has since[update] replaced him has director.[362]

In 2008, Google announced its "project 10100" which accepted ideas for how to help the community and then allowed Google users to vote on their favorites.[363] After two years of silence, during which many wondered what had happened to the program,[364] Google revealed the winners of the project, giving a total of ten million dollars to various ideas ranging from non-profit organizations that promote education to a website that intends to make all legal documents public and online.[365]

In March 2007, in partnership with the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI), Google hosted the first Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival at its headquarters in Mountain View.[366] In 2011, Google donated 1 million euros to International Mathematical Olympiad to support the next five annual International Mathematical Olympiads (2011–2015).[367][368] In July 2012, Google launched a "Legalize Love" campaign in support of gay rights.[369]

Tax avoidance

Google uses various tax avoidance strategies. Out of the five largest American technology companies, it pays the lowest taxes to the countries of origin of its revenues. Google between 2007 and 2010 saved $3.1 billion in taxes by shuttling non-U.S. profits through Ireland and the Netherlands and then to Bermuda. Such techniques lower its non-U.S. tax rate to 2.3 per cent, while normally the corporate tax rate in for instance the UK is 28 per cent.[370] This has reportedly sparked a French investigation into Google's transfer pricing practices.[371]

Following criticism of the amount of corporate taxes that Google paid in the United Kingdom, Chairman Eric Schmidt said, "It's called capitalism. We are proudly capitalistic." During the same December 2012 interview, Schmidt confirmed that the company had no intention of paying more to the UK exchequer.[372]

Google Vice-President Matt Brittin testified to the Public Accounts Committee of the UK House of Commons that his UK sales team made no sales and hence owed no sales taxes to the UK.[373] In January 2016, Google reached a settlement with the UK to pay £130m in back taxes plus higher taxes in future.[374]

In 2017, Google channeled $22.7 billion from the Netherlands to Bermuda to reduce its tax bill.[375]

Environment

Since 2007,[update] Google has aimed for carbon neutrality in regard to its operations.[376]

Google disclosed in September 2011 that it "continuously uses enough electricity to power 200,000 homes", almost 260 million watts or about a quarter of the output of a nuclear power plant. Total carbon emissions for 2010 were just under 1.5 million metric tons, mostly due to fossil fuels that provide electricity for the data centers. Google said that 25 percent of its energy was supplied by renewable fuels in 2010. An average search uses only 0.3 watt-hours of electricity, so all global searches are only 12.5 million watts or 5% of the total electricity consumption by Google.[377]

In 2007, Google launched a project centered on developing renewable energy, titled the "Renewable Energy Cheaper than Coal (RE<C)" project.[378] However, the project was canceled in 2014, after engineers Ross Koningstein and David Fork understood, after years of study, that "best-case scenario, which was based on our most optimistic forecasts for renewable energy, would still result in severe climate change", writing that they "came to the conclusion that even if Google and others had led the way toward a wholesale adoption of renewable energy, that switch would not have resulted in significant reductions in carbon dioxide emissions".[379]

In June 2013, The Washington Post reported that Google had donated $50,000 to the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank that calls human carbon emissions a positive factor in the environment and argues that global warming is not a concern.[380]

In July 2013, it was reported that Google had hosted a fundraising event for Oklahoma Senator Jim Inhofe, who has called climate change a "hoax".[381] In 2014 Google cut ties with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) after pressure from the Sierra Club, major unions and Google's own scientists because of ALEC's stance on climate change and opposition to renewable energy.[382]

In November 2017, Google bought 536 megawatts of wind power. The purchase made the firm reach 100% renewable energy. The wind energy comes from two power plants in South Dakota, one in Iowa and one in Oklahoma.[383]

Lobbying

In 2013, Google ranked 5th in lobbying spending, up from 213th in 2003. In 2012, the company ranked 2nd in campaign donations of technology and Internet sections.[384]

Litigation

Google has been involved in a number of lawsuits including the High-Tech Employee Antitrust Litigation which resulted in Google being one of four companies to pay a $415 million settlement to employees.[385]

On June 27, 2017, the company received a record fine of €2.42 billion from the European Union for "promoting its own shopping comparison service at the top of search results."[386] Commenting on the penalty, New Scientist magazine said: "The hefty sum – the largest ever doled out by the EU's competition regulators – will sting in the short term, but Google can handle it. Alphabet, Google’s parent company, made a profit of $2.5 billion (€2.2 billion) in the first six weeks of 2017 alone. The real impact of the ruling is that Google must stop using its dominance as a search engine to give itself the edge in another market: online price comparisons." The company disputed the ruling.[387]

On July 18, 2018,[388] the European Commission fined Google €4.34 billion for breaching EU antitrust rules. The abuse of dominant position has been referred to Google's constraint applied on Android device manufacturers and network operators to ensure that traffic on Android devices goes to the Google search engine. On October 9, 2018, Google confirmed[389] that it had appealed the fine to the General Court of the European Union.[390]

On January 21, 2019, French data regulator CNIL imposed a record €50 million fine on Google for breaching the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. The judgment claimed Google had failed to sufficiently inform users of its methods for collecting data to personalize advertising. Google issued a statement saying it was “deeply committed” to transparency and was “studying the decision” before determining its response.[391]

On March 20, 2019, the European Commission imposed a €1.49 billion ($1.69 billion) fine on Google for preventing rivals from being able to “compete and innovate fairly” in the online advertising market[392]. European Union competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said Google had violated EU antitrust rules by “imposing anti-competitive contractual restrictions on third-party websites” that required them to exclude search results from Google’s rivals. Kent Walker, Google’s senior vice-president of global affairs, said the company had “already made a wide range of changes to our products to address the Commission’s concerns,” and that "we'll be making further updates to give more visibility to rivals in Europe."[393]

Criticism and controversy

Google's market dominance has led to prominent media coverage, including criticism of the company over issues such as aggressive tax avoidance,[394] search neutrality, copyright, censorship of search results and content,[395] and privacy.[396][397] Other criticisms include alleged misuse and manipulation of search results, its use of others' intellectual property, concerns that its compilation of data may violate people's privacy, and the energy consumption of its servers, as well as concerns over traditional business issues such as monopoly, restraint of trade, anti-competitive practices, and patent infringement.

Former Deputy Defense Secretary Robert O. Work in 2018 criticizes Google and its employees have stepped into a Moral Hazard for themselves as not continuing Pentagon's artificial intelligence project while helping the autocratic communist China's AI technology that could be used against the United States in a conflict. He described Google as hypocritical, given it has opened an AI center in China and “Anything that’s going on in the AI center in China is going to the Chinese government and then will ultimately end up in the hands of the Chinese military." Work said. “I didn’t see any Google employee saying, ‘Hmm, maybe we shouldn’t do that.'” Google's dealings with China is decrying as unpatriotic.[398][399][400][401]

Google adhered to the Internet censorship policies of China,[402] enforced by means of filters colloquially known as "The Great Firewall of China". The Intercept reported in August 2018 that Google is developing for the people's Republic of China a censored version of its search engine (known as Dragonfly) "that will blacklist websites and search terms about human rights, democracy, religion, and peaceful protest".[403][404]

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford also criticizes Google as "it’s inexplicable" that it continue investing in autocratic communist China, who uses censorship technology to restrain freedoms and crackdown people there and has long history of intellectual property and patent theft which hurts U.S. companies, while simultaneously not renewing further research and development collaborations with the Pentagon. He said “I’m not sure that people at Google will enjoy a world order that is informed by the norms and standards of Russia or China.” He urges Google work directly with the U.S. government instead of making controversial inroads into China. Senator Mark Warner (D-VA) criticized Dragonfly evidences China's success at "recruit[ing] Western companies to their information control efforts" while China exports cyber and censorship infrastructure to authoritarian regimes like Venezuela, Ethiopia, and Pakistan.[405][406][407]

Google's mission statement, from the outset, was "to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful",[408] and its unofficial slogan is "Don't be evil".[409] In October 2015, a related motto was adopted in the Alphabet corporate code of conduct by the phrase: "Do the right thing".[410] The original motto was retained in the code of conduct of Google, now a subsidiary of Alphabet.[11]

Google's commitment to such robust idealism has been increasingly called into doubt due to a number of the firm's actions and behaviors which appear to contradict this.[411][412]

Following media reports about PRISM, NSA's massive electronic surveillance program, in June 2013, several technology companies were identified as participants, including Google.[413] According to leaks of said program, Google joined the PRISM program in 2009.[414]

On August 8, 2017, Google fired employee James Damore after he distributed a memo throughout the company which argued that "Google's ideological echo chamber" and bias clouded their thinking about diversity and inclusion, and that it is also biological factors, not discrimination alone, that cause the average woman to be less interested than men in technical positions.[415] Google CEO Sundar Pichai accused Damore in violating company policy by "advancing harmful gender stereotypes in our workplace", and he was fired on the same day.[416][417][418] New York Times columnist David Brooks argued Pichai had mishandled the case, and called for his resignation.[419][420]

Reportedly, Google's influenced New America think tank to expel their Open Markets research group, after the group has criticized Google monopolistic power and supported the EU $2.7B fine of Google.[421][422]

Google has worked with the United States Department of Defense on drone software through the 2017 "Project Maven" that could be used to improve the accuracy of drone strikes.[423] Thousands of Google employees, including senior engineers, have signed a letter urging Google CEO Sundar Pichai to end a controversial contract with the Pentagon.[424] In response to the backlash, Google ultimately decided to not renew their DoD contract, set to expire in 2019.[425]

Legal controversies

In 2017, David Elliot and Chris Gillespie argued before the Ninth Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals that "google" had suffered genericide. The controversy began in 2012 when Gillespie acquired 763 domain names containing the word "google." Google promptly filed a complaint with the National Arbitration Forum (NAF). Elliot then filed a petition for canceling the Google trademark. Ultimately, the court ruled in favor of Google because Elliot failed to show a preponderance of evidence showing the genericide of "google."[426]

On 10 December 2018, a New Zealand court ordered that the name of a man accused of murdering British traveller Grace Millane be withheld from the public. The next morning, Google named the man in an email it sent people who had subscribed to "what's trending in New Zealand".[427] Lawyers warned that this could compromise the trial, and Justice Minister Andrew Little said that Google was in contempt of court.[428][429] Google said that it had been unaware of the court order, and that the email had been created by algorithms.

On 21 January 2019, Google was fined €50 million (US$57 million) for violating the GDPR.[430] It is the biggest fine issued by CNIL for violation of the regulation.[431]

See also

- AngularJS

- Comparison of web search engines

- Don't be evil

- Google (verb)

- Google Balloon Internet

- Google Catalogs

- Google China

- Google bomb

- Google Chrome Experiments

- Google Get Your Business Online

- Google logo

- Google Maps

- Google platform

- Google Street View

- Google tax

- Google Ventures – venture capital fund

- Google X

- Life sciences division of Google X

- Googlebot – web crawler

- Googlization

- List of Google apps for Android

- List of mergers and acquisitions by Alphabet

- Living Stories

- Apple, Inc.

- Outline of Google

- Reunion

- Ungoogleable

- Surveillance capitalism

- Calico

References

- ^ "Company – Google". January 16, 2015. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Claburn, Thomas (September 24, 2008). "Google Founded By Sergey Brin, Larry Page... And Hubert Chang?!?". InformationWeek. UBM plc. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Locations — Google Jobs". Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ a b "Alphabet Announces Fourth Quarter 2018 Results" (PDF) (Press release). Mountain View, California: Alphabet Inc. February 4, 2019. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

Alphabet Inc. (NASDAQ: GOOG, GOOGL) today announced financial results for the quarter and fiscal year ended December 31, 2018. [...] Q1 2018 financial highlights[:] The following summarizes our consolidated financial results for the quarters ended December 31, 2017 and 2018 [...]: [...] Number of employees [as of] Three Months Ended December 31, 2018 [is] 98,771[.]

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Alphabet Finishes Reorganization With New XXVI Company". Bloomberg L.P. September 1, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Rivas, Teresa. "Ranking The Big Four Tech Stocks: Google Is No. 1, Apple Comes In Last". www.barrons.com. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Bloomberg - Are you a robot?". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ Sam Byford, The Verge. "Google Station is a new platform that aims to make public Wi-Fi better." September 27, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "google.com Traffic Statistics". Alexa Internet. November 25, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ "Google is now the world's most valuable brand". The Independent. February 1, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ a b "Google Code of Conduct". Alphabet. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Conger, Kate. "Google Removes 'Don't Be Evil' Clause From Its Code of Conduct".

- ^ Williamson, Alan (January 12, 2005). "An evening with Google's Marissa Mayer". Alan Williamson. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Our history in depth". Google Company. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Page, Lawrence; Brin, Sergey; Motwani, Rajeev; Winograd, Terry (November 11, 1999). "The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web". Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 18, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Technology Overview". Google, Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Page, Larry (August 18, 1997). "PageRank: Bringing Order to the Web". Stanford Digital Library Project. Archived from the original on May 6, 2002. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Battelle, John (August 2005). "The Birth of Google". Wired. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Trex, Ethan. "9 People, Places & Things That Changed Their Names". Mental Floss. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "Backrub search engine at Stanford University". Archived from the original on December 24, 1996. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ Koller, David (January 2004). "Origin of the name "Google"". Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hanley, Rachael (February 12, 2003). "From Googol to Google". The Stanford Daily. Stanford University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ "Google! Beta website". Google, Inc. Archived from the original on February 21, 1999. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Google! Search Engine". Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 11, 1998. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Google! Search Engine". Stanford University. Archived from the original on December 1, 1998. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Google.com WHOIS, DNS, & Domain Info - DomainTools". WHOIS. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Craig Silverstein's website". Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 2, 1999. Retrieved October 12, 2010.