Maharashtra

Maharashtra | |

|---|---|

| State of Maharashtra | |

|

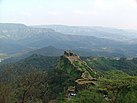

From top, left to right: Ajanta Caves, Kailasa Temple at Ellora Caves, Pratapgad Fort (near Mahabaleshwar) located in the Western Ghats, statue of Chatrapati outside Raigad fort, Shaniwar Wada, Hazur Sahib Nanded, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, The Gateway of India | |

| Etymology: "mahā" (Great) and Sanskritized form of "Ratta dynasty" | |

| Nickname: "Gateway of India" | |

| Motto(s): Pratipaccandralēkhēva vardhiṣṇurviśva vanditā Mahārāṣṭrasya rājyasya mudrā bhadrāya rājatē (The glory of Maharashtra will grow like the first day moon. It will be worshipped by the world and will shine only for the well-being of people) | |

| Anthem: Jai Jai Mahārāṣṭra Mājhā[1] ("Victory to My Maharashtra!")[2] | |

Location of Maharashtra in India | |

| Coordinates: 18°58′N 72°49′E / 18.97°N 72.82°E | |

| Country | India |

| Region | West India |

| Before was | State of Bombay (1950–1960) |

| Formation (by bifurcation) | 1 May 1960 |

| Capital | Mumbai Nagpur (winter) |

| Largest city | Mumbai |

| Largest metro | Mumbai Metropolitan Region |

| Districts | 36 (6 divisions) |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Maharashtra |

| • Governor | C. P. Radhakrishnan |

| • Chief minister | Eknath Shinde (SHS) |

| • Deputy chief minister | Devendra Fadnavis (BJP) Ajit Pawar (NCP) |

| State Legislature | Bicameral Maharashtra Legislature |

| • Council | Maharashtra Legislative Council (78 seats) |

| • Assembly | Maharashtra Legislative Assembly (288 seats) |

| National Parliament | Parliament of India |

| • Rajya Sabha | 19 seats |

| • Lok Sabha | 48 seats |

| High Court | Bombay High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 307,713 km2 (118,809 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 870 km (540 mi) |

| • Width | 605 km (376 mi) |

| Elevation | 100 m (300 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,646 m (5,400 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −1 m (−3 ft) |

| Population (2011)[5] | |

| • Total | |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 370/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 45.22% |

| • Rural | 54.78% |

| Demonym | Maharashtrian |

| Language | |

| • Official | Marathi[6][7] |

| • Official script | Devanagari script |

| GDP | |

| • Total (2024–25) | |

| • Rank | (1st) |

| • Per capita | |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-MH |

| Vehicle registration | MH |

| HDI (2022) | |

| Literacy (2017) | |

| Sex ratio (2021) | 966♀/1000 ♂[12] (23rd) |

| Website | maharashtra |

| Symbols of Maharashtra | |

| |

| Song | Jai Jai Mahārāṣṭra Mājhā[1] ("Victory to My Maharashtra!")[2] |

| Foundation day | Maharashtra Day |

| Bird | Yellow-footed green pigeon[13] |

| Butterfly | Blue Mormon[14] |

| Fish | Silver Pomfret |

| Flower | Jarul[13][15] |

| Mammal | Indian giant squirrel[13] |

| Tree | Mango tree[13][16] |

| State highway mark | |

| |

| State highway of Maharashtra MH SH1-MH SH368 | |

| List of Indian state symbols | |

| ^The State of Bombay was split into two States i.e. Maharashtra and Gujarat by the Bombay Reorganisation Act 1960[17] †† Common high court | |

Maharashtra (ISO: Mahārāṣṭra; Marathi: [məhaːɾaːʂʈɾə] ) is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to the southeast and Chhattisgarh to the east, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh to the north, and the Indian union territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu to the northwest.[18] Maharashtra is the second-most populous state in India.

The state is divided into 6 divisions and 36 districts, Mumbai, is the capital of Maharashtra due to its historical significance as a major trading port and its status as India's financial hub, housing key institutions and a diverse economy. Additionally, its well-developed infrastructure and cultural diversity make it a suitable administrative center for the state. the most populous urban area in India, and Nagpur serving as the winter capital.[19] The Godavari and Krishna are the state's two major rivers, and forests cover 16.47% of the state's geographical area. The state is home to six UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Ajanta Caves, Ellora Caves, Elephanta Caves, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus), the Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Mumbai and the Western Ghats, a heritage site made up of 39 individual properties of which 4 are in Maharashtra.[20][21]

The economy of Maharashtra is the largest in India, with a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹42.5 trillion (US$510 billion) and GSDP per capita of ₹335,247 (US$4,000);[9] it is the single-largest contributor to India's economy, being accountable for 14% of all-India nominal GDP.[22][23][24] The service sector dominates the state's economy, accounting for 69.3% of the value of the output of the country. Although agriculture accounts for 12% of the state GDP, it employs nearly half the population of the state.

Maharashtra is one of the most industrialised states in India. The state's capital, Mumbai, is India's financial and commercial capital.[25] The Bombay Stock Exchange, India's largest stock exchange and the oldest in Asia, is located in the city, as is the National Stock Exchange, which is the second-largest stock exchange in India and one of world's largest derivatives exchanges. The state has played a significant role in the country's social and political life and is widely considered a leader in terms of agricultural and industrial production, trade and transport, and education.[26] Maharashtra is the ninth-highest ranking among Indian states in the human development index.[27]

The region that encompasses the modern state has a history going back many millennia. Notable dynasties that ruled the region include the Asmakas, the Mauryas, the Satavahanas, the Western Satraps, the Abhiras, the Vakatakas, the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Western Chalukyas, the Seuna Yadavas, the Khaljis, the Tughlaqs, the Bahamanis and the Mughals. In the early nineteenth century, the region was divided between the Dominions of the Peshwa in the Maratha Confederacy and the Nizamate of Hyderabad.

After two wars and the proclamation of the Indian Empire, the region became a part of the Bombay Province, the Berar Province and the Central Provinces of India under direct British rule and the Deccan States Agency under Crown suzerainty. Between 1950 and 1956, the Bombay Province became the Bombay State in the Indian Union, and Berar, the Deccan states and the Gujarat states were merged into the Bombay State. Aspirations of a separate state for Marathi-speaking peoples were pursued by the United Maharashtra Movement; their advocacy eventually borne fruit on 1 May 1960, when the State of Bombay was bifurcated into the states of Maharasthra and Gujarat.

Etymology

The modern Marathi language evolved from Maharashtri Prakrit,[28] and the word Marhatta (later used for the Marathas) is found in the Jain Maharashtrian literature. The term Maharashtra along with Maharashtrian, Marathi, and Maratha may have derived from the same root. However, their exact etymology is uncertain.[29]

The most widely accepted theory among the linguistic scholars is that the words Maratha and Maharashtra ultimately derived from a combination of Mahā and Rāṣṭrikā,[29][30] the name of a tribe or dynasty of chiefs ruling in the Deccan region.[31] An alternate theory states that the term is derived from mahā ("great") and ratha/rathi ("chariot"/"charioteer"), which refers to a skilful northern fighting force that migrated southward into the area.[31][30]

In the Harivamsa, the Yadava kingdom called Anaratta is described as mostly inhabited by the Abhiras (Abhira-praya-manusyam). The Anartta country and its inhabitants were called Surastra and the Saurastras, probably after the Rattas (Rastras) akin to the Rastrikas of Asoka's rock Edicts, now known as Maharastra and the Marattas.[32]

An alternative theory states that the term derives from the word mahā ("great") and rāṣṭra ("nation/dominion").[33] However, this theory is somewhat controversial among modern scholars who believe it to be the Sanskritised interpretation of later writers.[29]

History

Numerous Late Harappan or Chalcolithic sites belonging to the Jorwe culture (c. 1300–700 BCE) have been discovered throughout the state.[34][35] The largest settlement discovered of the culture is at Daimabad, which had a mud fortification during this period, as well as an elliptical temple with fire pits.[36][37] In the Late Harappan period there was a large migration of people from Gujarat to northern Maharashtra.[38]

Maharashtra was ruled by Maurya Empire in the fourth and third centuries BCE. Around 230 BCE, Maharashtra came under the rule of the Satavahana dynasty which ruled it for the next 400 years.[39] The rule of Satavahanas was followed by that of Western Satraps, Gupta Empire, Gurjara-Pratihara, Vakataka, Kadambas, Chalukya Empire, Rashtrakuta Dynasty, and Western Chalukya and the Yadava Dynasty. The Buddhist Ajanta Caves in present-day Aurangabad display influences from the Satavahana and Vakataka styles. The caves were possibly excavated during this period.[40]

The Chalukya dynasty ruled the region from the sixth to the eighth centuries CE, and the two prominent rulers were Pulakeshin II, who defeated the north Indian Emperor Harsha, and Vikramaditya II, who defeated the Arab invaders in the eighth century. The Rashtrakuta dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the eighth to the tenth century.[41] The Arab traveller Sulaiman al Mahri described the ruler of the Rashtrakuta dynasty Amoghavarsha as "one of the four great kings of the world".[42] Shilahara dynasty began as vassals of the Rashtrakuta dynasty which ruled the Deccan plateau between the eighth and tenth centuries. From the early 11th century to the 12th century, the Deccan Plateau, which includes a significant part of Maharashtra, was dominated by the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty.[43] Several battles were fought between the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty in the Deccan Plateau during the reigns of Raja Raja Chola I, Rajendra Chola I, Jayasimha II, Someshvara I, and Vikramaditya VI.[44]

In the early 14th century, the Yadava dynasty, which ruled most of present-day Maharashtra, was overthrown by the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji. Later, Muhammad bin Tughluq conquered parts of the Deccan, and temporarily shifted his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in Maharashtra. After the collapse of the Tughluqs in 1347, the local Bahmani Sultanate of Gulbarga took over, governing the region for the next 150 years.[45] After the break-up of the Bahamani sultanate in 1518, Maharashtra split into five Deccan Sultanates: Nizamshah of Ahmednagar, Adilshah of Bijapur, Qutubshah of Golkonda, Bidarshah of Bidar and Imadshah of Elichpur. These kingdoms often fought with each other. United, they decisively defeated the Vijayanagara Empire of the south in 1565.[46] The present area of Mumbai was ruled by the Sultanate of Gujarat before its capture by Portugal in 1535 and the Faruqi dynasty ruled the Khandesh region between 1382 and 1601 before finally getting annexed in the Mughal Empire. Malik Ambar, the regent of the Nizamshahi dynasty of Ahmednagar from 1607 to 1626,[47] increased the strength and power of Murtaza Nizam Shah II and raised a large army.Ambar is said to have introduced the concept of guerrilla warfare in the Deccan region.[48] Malik Ambar assisted Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in Delhi against his stepmother, Nur Jahan, who wanted to enthrone her son-in-law.[49][50] Both Shivaji's grandfather, Maloji and father Shahaji served under Ambar.[51]

In the early 17th century, Shahaji Bhosale, an ambitious local general who had served the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, the Mughals and Adil Shah of Bijapur at different periods throughout his career, attempted to establish his independent rule.[52] This attempt was unsuccessful, but his son Shivaji succeeded in establishing the Maratha Empire.[53] Shortly after Shivaji's death in 1680, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb launched a campaign to conquer Maratha territories as well as the Adilshahi and Govalkonda kingdoms.[54] This campaign, better known as Mughal–Maratha Wars, was a strategic defeat for Mughals. Aurangzeb failed to fully conquer Maratha territories, and this campaign had a ruinous effect on Mughal Treasury and Army.[55] Shortly after Aurangzeb's death in 1707, Marathas under Peshwa Bajirao I and the generals that he had promoted such as Ranoji Shinde and Malharrao Holkar started conquering Mughal Territories in the north and western India, and by 1750s they or their successors had confined the Mughals to city of Delhi.[56]

After their defeat at the hand of Ahmad Shah Abdali's Afghan forces in the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761, the Maratha suffered a setback. However, they soon reclaimed the lost territories and ruled central and north India including Delhi until the end of the eighteenth century. The Marathas also developed a potent Navy circa in the 1660s, which at its peak under the command of Kanhoji Angre, dominated the territorial waters of the western coast of India from Mumbai to Savantwadi.[57] It resisted the British, Portuguese, Dutch, and Siddi naval ships and kept a check on their naval ambitions. Charles Metcalfe, British Civil servant and later Acting Governor-General, said in 1806:[58]

India contains no more than two great powers, British and Maratha, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.

The British East India Company slowly expanded areas under its rule during the 18th century. The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) led to the end of the Maratha Empire and the East India Company took over the empire.[59][60] The Maratha Navy dominated till around the 1730s, was in a state of decline by the 1770s and ceased to exist by 1818.[61]

The British governed western Maharashtra as part of the Bombay Presidency, which spanned an area from Karachi in Pakistan to northern Deccan. A number of the Maratha states persisted as princely states, retaining autonomy in return for acknowledging British suzerainty. The largest princely states in the territory were Nagpur, Satara and Kolhapur State; Satara was annexed to the Bombay Presidency in 1848, and Nagpur was annexed in 1853 to become Nagpur Province, later part of the Central Provinces. Berar, which had been part of the Nizam of Hyderabad's kingdom, was occupied by the British in 1853 and annexed to the Central Provinces in 1903.[62] However, a large region called Marathwada remained part of the Nizam's Hyderabad State throughout the British period. The British ruled Maharashtra region from 1818 to 1947 and influenced every aspect of life for the people of the region. They brought several changes to the legal system,[63][64][65] built modern means of transport including roads[66] and Railways,[67][68] took various steps to provide mass education, including that for previously marginalised classes and women,[69] established universities based on western system and imparting education in science, technology,[70] and western medicine,[71][72][73] standardised the Marathi language,[74][75][76][77] and introduced mass media by utilising modern printing technologies.[78] The 1857 war of independence had many Marathi leaders, though the battles mainly took place in northern India. The modern struggle for independence started taking shape in the late 1800s with leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Pherozeshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji evaluating the company rule and its consequences. Jyotirao Phule was the pioneer of social reform in the Maharashtra region in the second half of the 19th century. His social work was continued by Shahu, Raja of Kolhapur and later by B. R. Ambedkar. After the partial autonomy given to the states by the Government of India Act 1935, B. G. Kher became the first chief minister of the Congress party-led government of tri-lingual Bombay Presidency.[79] The ultimatum to the British during the Quit India Movement was given in Mumbai and culminated in the transfer of power and independence in 1947.[citation needed]

After Indian independence, princely states and Jagirs of the Deccan States Agency were merged into Bombay State, which was created from the former Bombay Presidency in 1950.[80] In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act reorganised the Indian states along linguistic lines, and Bombay Presidency State was enlarged by the addition of the predominantly Marathi-speaking regions of Marathwada (Aurangabad Division) from erstwhile Hyderabad state and Vidarbha region from the Central Provinces and Berar. The southernmost part of Bombay State was ceded to Mysore. In the 1950s, Marathi people strongly protested against bilingual Bombay state under the banner of Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti.[81][82] The notable leaders of the samiti included Keshavrao Jedhe, S.M. Joshi, Shripad Amrit Dange, Pralhad Keshav Atre and Gopalrao Khedkar. The key demand of the samiti called for a Marathi speaking state with Mumbai as its capital.[83] In the Gujarati speaking areas of the state, a similar Mahagujarat Movement demanded a separate Gujarat state comprising majority Gujarati areas. After many years of protests, which saw 106 deaths amongst the protestors, and electoral success of the samiti in 1957 elections, the central government led by Prime minister Nehru split Bombay State into two new states of Maharashtra and Gujarat on 1 May 1960.[84]

The state continues to have a dispute with Karnataka regarding the region of Belgaum and Karwar.[85][86] The Government of Maharashtra was unhappy with the border demarcation of 1957 and filed a petition to the Ministry of Home affairs of India.[87] Maharashtra claimed 814 villages, and 3 urban settlements of Belagon, Karwar and Nippani, all part of then Bombay Presidency before freedom of the country.[88] A petition by Maharashtra in the Supreme Court of India, staking a claim over Belagon, is currently pending.[89]

Geography

Maharashtra with a total area of 307,713 km2 (118,809 sq mi), is the third-largest state by area in terms of land area and constitutes 9.36% of India's total geographical area. The State lies between 15°35' N to 22°02' N latitude and 72°36' E to 80°54' E longitude. It occupies the western and central part of the country and has a coastline stretching 840 kilometres (520 mi)[90] along the Arabian Sea.[91] The dominant physical feature of the state is its plateau character, which is separated from the Konkan coastline by the mountain range of the Western Ghats, which runs parallel to the coast from north to south. The Western Ghats, also known as the Sahyadri Range, has an average elevation of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft); its slopes gently descending towards the east and southeast.[92] The Western Ghats (or the Sahyadri Mountain range) provide a physical barrier to the state on the west, while the Satpura Hills along the north and Bhamragad-Chiroli-Gaikhuri ranges on the east serve as its natural borders.[93] This state's expansion from North to South is 720 km (450 mi) and East to West is 800 km (500 mi). To the west of these hills lie the Konkan coastal plains, 50–80 km (31–50 mi) in width. To the east of the Ghats lies the flat Deccan Plateau. The main rivers of the state are the Krishna, and its tributary, Bhima, the Godavari, and its main tributaries, Manjara, and Wardha-Wainganga and the Tapi, and its tributary Purna.[91][94] Maharashtra is divided into five geographic regions. Konkan is the western coastal region, between the Western Ghats and the sea.[95] Khandesh is the north region lying in the valley of the Tapti, Purna river.[94] Nashik, Malegaon Jalgaon, Dhule and Bhusawal are the major cities of this region.[96] Desh is in the centre of the state.[97] Marathwada, which was a part of the princely state of Hyderabad until 1956, is located in the southeastern part of the state.[91][98] Aurangabad and Nanded are the main cities of the region.[99] Vidarbha is the easternmost region of the state, formerly part of the Central Provinces and Berar.[100]

The state has limited area under irrigation, low natural fertility of soils, and large areas prone to recurrent drought. Due to this the agricultural productivity of Maharashtra is generally low as compared to the national averages of various crops. Maharashtra has been divided in to nine agro-climatic zones on the basis of annual rainfall soil types, vegetation and cropping pattern.[101]

Climate

Maharashtra experiences a tropical wet and dry climate with hot, rainy, and cold weather seasons. Some areas more inland experience a hot semi arid climate, due to a rain shadow effect caused by the Western Ghats.[102] The month of March marks the beginning of the summer and the temperature rises steadily until June. In the central plains, summer temperatures rise to between 40 °C or 104.0 °F and 45 °C or 113.0 °F. May is usually the warmest and January the coldest month of the year. The winter season lasts until February with lower temperatures occurring in December and January. On the Deccan plateau that lies on eastern side of the Sahyadri mountains, the climate is drier, however, dew and hail often occur, depending on seasonal weather.[103]

The rainfall patterns in the state vary by the topography of different regions. The state can be divided into four meteorological regions, namely coastal Konkan, Western Maharashtra, Marathwada, and Vidarbha.[104] The southwest monsoon usually arrives in the last week of June and lasts till mid-September. Pre-monsoon showers begin towards the middle of June and post-monsoon rains occasionally occur in October. The highest average monthly rainfall is during July and August. In the winter season, there may be a little rainfall associated with western winds over the region. The Konkan coastal area, west of the Sahyadri Mountains receives very heavy monsoon rains with an annual average of more than 3,000 millimetres (120 in). However, just 150 km (93 mi) to the east, in the rain shadow of the mountain range, only 500–700 mm/year will fall, and long dry spells leading to drought are a common occurrence. Maharashtra has many of the 99 Indian districts identified by the Indian Central water commission as prone to drought.[105] The average annual rainfall in the state is 1,181 mm (46.5 in) and 75% of it is received during the southwest monsoon from June–to September. However, under the influence of the Bay of Bengal, eastern Vidarbha receives good rainfall in July, August, and September.[106] Thane, Raigad, Ratnagiri, and Sindhudurg districts receive heavy rains of an average of 2,000 to 2,500 mm or 80 to 100 in and the hill stations of Matheran and Mahabaleshwar over 5,000 mm (200 in). Contrariwise, the rain shadow districts of Nashik, Pune, Ahmednagar, Dhule, Jalgaon, Satara, Sangli, Solapur, and parts of Kolhapur receive less than 1,000 mm (39 in) annually. In winter, a cool dry spell occurs, with clear skies, gentle air breeze, and pleasant weather that prevails from October to February, although the eastern Vidarbha region receives rainfall from the north-east monsoon.[107]

Flora and fauna

The state has three crucial biogeographic zones, namely Western Ghats, Deccan Plateau, and the West coast. The Ghats nurture endemic species, Deccan Plateau provides for vast mountain ranges and grasslands while the coast is home to littoral and swamp forests. Flora of Maharashtra is heterogeneous in composition. In 2012 the recorded thick forest area in the state was 61,939 km2 (23,915 sq mi) which was about 20.13% of the state's geographical area.[108] There are three main Public Forestry Institutions (PFIs) in the Maharashtra state: the Maharashtra Forest Department (MFD), the Forest Development Corporation of Maharashtra (FDCM) and the Directorate of Social Forestry (SFD).[109] The Maharashtra State Biodiversity Board, constituted by the Government of Maharashtra in January 2012 under the Biological Diversity Act, 2002, is the nodal body for the conservation of biodiversity within and outside forest areas in the State.[110][111]

Maharashtra is ranked second among the Indian states in terms of the recorded forest area. Recorded Forest Area (RFA) in the state is 61,579 sq mi (159,489 km2) of which 49,546 sq mi (128,324 km2) is reserved forests, 6,733 sq mi (17,438 km2) is protected forest and 5,300 sq mi (13,727 km2) is unclassed forests. Based on the interpretation of IRS Resourcesat-2 LISS III satellite data of the period Oct 2017 to Jan 2018, the State has 8,720.53 sq mi (22,586 km2) under Very Dense Forest(VDF), 20,572.35 sq mi (53,282 km2) under Moderately Dense Forest (MDF) and 21,484.68 sq mi (55,645 km2) under Open Forest (OF). According to the Champion and Seth classification, Maharashtra has five types of forests:[112]

- Southern Tropical Semi-Evergreen forests - These are found in the western ghats at a height of 400–1,000 m (1,300–3,300 ft). Anjani, Hirda, Kinjal, and Mango are predominant tree species found here.

- Southern Tropical Moist Deciduous forests-These are a mix of Moist Teak bearing forests (Melghat) and Moist Mixed deciduous forests (Vidarbha and Thane district). Commercially important Teak, Shishum, and bamboo are found here. In addition to evergreen Teak, some of the other tree species found in this type of forest include Jambul, Ain, and Shisam.[113]

- Southern Tropical Dry Deciduous forests-these occupy a major part of the state. Southern Tropical Thorn forests are found in the low rainfall regions of Marathwada, Vidarbha, Khandesh, and Western Maharashtra. At present, these forests are heavily degraded. Babul, Bor, and Palas are some of the tree species found here.

- Littoral and Swamp forests are mainly found in the Creeks of Sindhudurg and Thane districts of the coastal Konkan region. The state harbours significant mangrove, coastal and marine biodiversity, with 304 km2 (117 sq mi) of the area under mangrove cover as per the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) of the Forest survey India in the coastal districts of the state.

The most common animal species present in the state are monkeys, wild pigs, tiger, leopard, gaur, sloth bear, sambar, four-horned antelope, chital, barking deer, mouse deer, small Indian civet, golden jackal, jungle cat, and hare.[114] Other animals found in this state include reptiles such as lizards, scorpions and snake species such as cobras and kraits.[115] The state provides legal protection to its tiger population through six dedicated tiger reserves under the precincts of the National Tiger Conservation Authority.

The state's 720 km (450 mi) of sea coastline of the Arabian Sea marks the presence of various types of fish and marine animals. The Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) found 1527 marine animal species, including molluscs with 581 species, many crustacean species including crabs, shrimps, and lobsters, 289 fish species, and 141 species types of annelids (sea worms).[116]

Regions, divisions and districts

Maharashtra has following geographical regions:

- North Maharashtra

- Konkan

- Marathwada

- Vidarbha

- Desh or Western Maharashtra

It consists of six administrative divisions:[117]

The state's six divisions are further divided into 36 districts, 109 sub-divisions, and 358 talukas.[118] Maharashtra's top five districts by population, as ranked by the 2011 Census, are listed in the following table.

Each district is governed by a district collector or district magistrate, appointed either by the Indian Administrative Service or the Maharashtra Civil Service.[119] Districts are subdivided into sub-divisions (Taluka) governed by sub-divisional magistrates, and again into blocks.[120] A block consists of panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities.[121][122] Talukas are intermediate level panchayat between the Zilla Parishad (district councils) at the district level and gram panchayat (village councils) at the lower level.[120][123]

Out of the total population of Maharashtra, 45.22% of people live in urban regions. The total figure of the population living in urban areas is 50.8 million. There are 27 Municipal Corporations in Maharashtra.[124]

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mumbai  Pune |

1 | Mumbai | Mumbai City district | 18,414,288 | 11 | Kolhapur | Kolhapur | 660,861 |  Nagpur  Nashik |

| 2 | Pune | Pune | 5,049,968 | 12 | Sangli | Sangli | 650,000 | ||

| 3 | Nagpur | Nagpur | 2,497,777 | ||||||

| 4 | Nashik | Nashik | 2,362,769 | ||||||

| 5 | Thane | Thane | 1,886,941 | ||||||

| 6 | Aurangabad | Aurangabad | 1,189,376 | ||||||

| 7 | Solapur | Solapur | 951,118 | ||||||

| 8 | Amravati | Amravati | 846,801 | ||||||

| 9 | Jalgaon | Jalgaon | 737,411 | ||||||

| 10 | Nanded | Nanded | 550,564 | ||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,391,643 | — |

| 1911 | 21,474,523 | +10.7% |

| 1921 | 20,849,666 | −2.9% |

| 1931 | 23,959,300 | +14.9% |

| 1941 | 26,832,758 | +12.0% |

| 1951 | 32,002,564 | +19.3% |

| 1961 | 39,553,718 | +23.6% |

| 1971 | 50,412,235 | +27.5% |

| 1981 | 62,782,818 | +24.5% |

| 1991 | 78,937,187 | +25.7% |

| 2001 | 96,878,627 | +22.7% |

| 2011 | 112,374,333 | +16.0% |

| Source: Census of India[125] | ||

According to the provisional results of the 2011 national census, Maharashtra was at that time the richest state in India and the second-most populous state in India with a population of 112,374,333. Contributing to 9.28% of India's population, males and females are 58,243,056 and 54,131,277, respectively.[126] The total population growth in 2011 was 15.99%, while in the previous decade it was 22.57%.[127][128] Since independence, the decadal growth rate of population has remained higher (except in the year 1971) than the national average. However, in the year 2011, it was found to be lower than the national average.[128] The 2011 census for the state found 55% of the population to be rural with 45% being urban-based.[129][130] Although, India hasn't conducted a caste-wise census since Independence, based on the British era census of 1931, it is estimated that the Maratha and the Maratha-kunbi numerically form the largest caste cluster with around 32% of the population.[131] Maharashtra has a large Other Backward Class population constituting 41% of the population. The scheduled tribes include Adivasis such as Thakar, Warli, Konkana and Halba.[132] The 2011 census found scheduled castes and scheduled tribes to account for 11.8% and 8.9% of the population, respectively.[133] The state also includes a substantial number of migrants from other states of India.[134] Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and Karnataka account for the largest percentage of migrants to the Mumbai metropolitan area.[135]

The 2011 census reported the human sex ratio is 929 females per 1000 males, which were below the national average of 943. The density of Maharashtra was 365 inhabitants per km2 which was lower than the national average of 382 per km2. Since 1921, the populations of Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg shrank by −4.96% and −2.30%, respectively, while the population of Thane grew by 35.9%, followed by Pune at 30.3%. The literacy rate is 83.2%, higher than the national rate at 74.04%.[136] Of this, male literacy stood at 89.82% and female literacy 75.48%.[137]

Religion

According to the 2011 census, Hinduism was the principal religion in the state at 79.8% of the total population. Muslims constituted 11.5% of the total population. Maharashtra has the highest number of followers of Buddhism in India, accounting for 5.8% of Maharashtra's total population with 6,531,200 followers. Marathi Buddhists account for 77.36% of all Buddhists in India.[139] Sikhs, Christians, and Jains constituted 0.2%, 1%, and 1.2% of the Maharashtra population respectively.[138]

Maharashtra, and particularly the city of Mumbai, is home to two tiny religious communities. This includes 5000 Jews, mainly belonging to the Bene Israel, and Baghdadi Jewish communities.[140] Parsi is the other community who follow Zoroastrianism. The 2011 census recorded around 44,000 parsis in Maharashtra.[141]

Language

Marathi is the official language although different regions have their own dialects.[6][143][144] Most people speak regional languages classified as dialects of Marathi in the census. Powari, Lodhi, and Varhadi are spoken in the Vidarbha region, Dangi is spoken near the Maharashtra-Gujarat border, Bhil languages are spoken throughout the northwest part of the state, Khandeshi (locally known as Ahirani) is spoken in Khandesh region. In the Desh and Marathwada regions, Dakhini Urdu is widely spoken, although Dakhini speakers are usually bilingual in Marathi.[145]

Konkani, and its dialect Malvani, is spoken along the southern Konkan coast. Telugu and Kannada are spoken along the border areas of Telangana and Karnataka, respectively. At the junction of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Chhattisgarh a variety of Hindi dialects are spoken such as Lodhi and Powari. Lambadi is spoken through a wide area of eastern Marathwada and western Vidarbha. Gondi is spoken by diminishing minorities throughout Vidarbha but is most concentrated in the forests of Gadchiroli and the Telangana border.[citation needed]

Marathi is the first language of a majority or plurality of the people in all districts of Maharashtra except Nandurbar, where Bhili is spoken by 45% of its population. The highest percentage of Khandeshi speakers are Dhule district (29%) and the highest percentage of Gondi speakers are in Gadchiroli district (24%).[142]

The highest percentages of mother-tongue Hindi speakers are in urban areas, especially Mumbai and its suburbs, where it is mother tongue to over a quarter of the population. Pune and Nagpur are also spots for Hindi-speakers. Gujarati and Urdu are also major languages in Mumbai, both are spoken by around 10% of the population.[142] Urdu and its dialect, the Dakhni are spoken by the Muslim population of the state.[146]

The Mumbai metropolitan area is home to migrants from all over India. In Mumbai, a wide range of languages are spoken, including Telugu, Tamil, Konkani, Kannada, Sindhi, Punjabi, Bengali, Tulu, and many more.[142]

Governance and administration

The state is governed through a parliamentary system of representative democracy, a feature the state shares with other Indian states. Maharashtra is one of the six states in India where the state legislature is bicameral, comprising the Vidhan Sabha (Legislative Assembly) and the Vidhan Parishad (Legislative Council).[147] The legislature, the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly, consists of elected members and special office bearers such as the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, who are elected by the members. The Legislative Assembly consists of 288 members who are elected for five-year terms unless the Assembly is dissolved before to the completion of the term. The Legislative Council is a permanent body of 78 members with one-third (33 members) retiring every two years. Maharashtra is the second most important state in terms of political representation in the Lok Sabha, or the lower chamber of the Indian Parliament with 48 seats which is next only to Uttar Pradesh which has the highest number of seats than any other Indian state with 80 seats.[148] Maharashtra also has 19 seats in the Rajya Sabha, or the upper chamber of the Indian Parliament.[149][150]

The government of Maharashtra is a democratically elected body in India with the Governor as its constitutional head who is appointed by the President of India for a five-year term.[151] The leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the chief minister by the governor, and the Council of Ministers are appointed by the governor on the advice of the chief minister.[152] The governor remains a ceremonial head of the state, while the chief minister and his council are responsible for day-to-day government functions. The council of ministers consists of Cabinet Ministers and Ministers of State (MoS). The Secretariat headed by the Chief Secretary assists the council of ministers. The Chief Secretary is also the administrative head of the government. Each government department is headed by a Minister, who is assisted by an Additional Chief Secretary or a Principal Secretary, who is usually an officer of the Indian Administrative Service, the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary serves as the administrative head of the department they are assigned to. Each department also has officers of the rank of Secretary, Special Secretary, Joint Secretary, etc. assisting the Minister and the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary.[citation needed]

For purpose of administration, the state is divided into 6 divisions and 36 districts. Divisional Commissioner, an IAS officer is the head of administration at the divisional level. The administration in each district is headed by a District Magistrate, who is an IAS officer and is assisted by several officers belonging to state services. Urban areas in the state are governed by Municipal Corporations, Municipal Councils, Nagar Panchayats, and seven Cantonment Boards.[128][153] The Maharashtra Police is headed by an IPS officer of the rank of Director general of police. A Superintendent of Police, an IPS officer assisted by the officers of the Maharashtra Police Service, is entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining law and order and related issues in each district. The Divisional Forest Officer, an officer belonging to the Indian Forest Service, manages the forests, environment, and wildlife of the district, assisted by the officers of Maharashtra Forest Service and Maharashtra Forest Subordinate Service.[154]

The judiciary in the state consists of the Maharashtra High Court (The High Court of Bombay), district and session courts in each district and lower courts and judges at the taluka level.[155] The High Court has regional branches at Nagpur and Aurangabad in Maharashtra and Panaji which is the capital of Goa.[156] The state cabinet on 13 May 2015 passed a resolution favouring the setting up of one more bench of the Bombay high court in Kolhapur, covering the region.[157] The President of India appoints the chief justice of the High Court of the Maharashtra judiciary on the advice of the chief justice of the Supreme Court of India as well as the Governor of Maharashtra.[158] Other judges are appointed by the chief justice of the high court of the judiciary on the advice of the Chief Justice.[159] Subordinate Judicial Service is another vital part of the judiciary of Maharashtra.[160] The subordinate judiciary or the district courts are categorised into two divisions: the Maharashtra civil judicial services and higher judicial service.[161] While the Maharashtra civil judicial services comprises the Civil Judges (Junior Division)/Judicial Magistrates and civil judges (Senior Division)/Chief Judicial Magistrate, the higher judicial service comprises civil and sessions judges.[162] The Subordinate judicial service of the judiciary is controlled by the District Judge.[159][163]

Politics

The politics of the state in the first decades after its formation in 1960 was dominated by the Indian National Congress party or its offshoots such as the Nationalist Congress Party. At present, it has been dominated by four political parties, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Nationalist Congress Party, the Indian National Congress and the Shivsena.The politics of the state in the last five years has seen long term alliances breaking up like that of undivided Shivsena and BJP, new ones being formed between Congress, NCP, and the Shivsena, regional parties like the Shivsena and NCP splitting up, and majority of their legislators joining a new alliance government with the BJP.[citation needed]

Just like in other states in India, dynastic politics is fairly common also among political parties in Maharashtra.[164] The dynastic phenomenon is seen from the national level down to the district level and even village level. The three-tier structure of Panchayati Raj created in the state in the 1960s also helped to create and consolidate this phenomenon in rural areas. Apart from controlling the government, political families also control cooperative institutions, mainly cooperative sugar factories and district cooperative banks in the state.[165] The Bharatiya Janata Party also features several senior leaders who are dynasts.[166][167] In Maharashtra, the NCP has a particularly high level of dynasticism.[167]

In the early years, the politics of Maharashtra was dominated by Congress party figures such as Yashwantrao Chavan, Vasantdada Patil, Vasantrao Naik, and Shankarrao Chavan. Sharad Pawar, who started his political career in the Congress party, has been a towering personality in state and national politics for over forty years. During his career, he has split the Congress twice with significant consequences for the state politics.[168][169] The Congress party enjoyed a near unchallenged dominance of the political landscape until 1995 when the Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) secured an overwhelming majority in the state to form a coalition government.[170] After his second parting from the Congress party in 1999, Sharad Pawar founded the NCP but then formed a coalition with the Congress to keep out the BJP-Shiv Sena combine out of the Maharashtra state government for fifteen years until September 2014. Prithviraj Chavan of the Congress party was the last Chief Minister of Maharashtra under the Congress-NCP alliance.[171][172][173] For the 2014 assembly polls, the two alliances between NCP and Congress and that between BJP and Shiv Sena respectively broke down over seat allocations. In the election, the largest number of seats went to the Bharatiya Janata Party, with 122 seats. The BJP initially formed a minority government under Devendra Fadnavis. The Shiv Sena entered the Government after two months and provided a comfortable majority for the alliance in the Maharashtra Vidhansabha for the duration of the assembly.[174] In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP-Shiv Sena alliance secured 41 seats out of 48 from the state.[175] Later in 2019, the BJP and Shiv Sena alliance fought the assembly elections together but the alliance broke down after the election over the post of the chief minister. Uddhav Thackeray of Shiv Sena then formed an alternative governing coalition under his leadership with his erstwhile opponents from NCP, INC, and several independent members of the legislative assembly.[176][177] Thackeray served as the 19th Chief minister of Maharashtra of the Maha Vikas Aghadi coalition until June 2022.[178][179][180]

In late June 2022, Eknath Shinde, a senior Shiv Sena leader, and the majority of MLAs from Shiv Sena joined hands with the BJP.[181][182][183] Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari called for a trust vote, an action that would later on be described as a "sad spectacle" by Supreme Court of India,[184] and draw criticism from Political Observers.[185] Uddhav Thackeray resigned from the post as chief minister well as a MLC member ahead of no-confidence motion on 29 June 2022.[186] Shinde subsequently formed a new coalition with the BJP, and was sworn in as the Chief Minister on 30 June 2022.[187] BJP leader, Devendra Fadnavis was given the post of Deputy Chief Minister in the new government.[187] Uddhav Thackeray filed a lawsuit in Supreme Court of India claiming that Eknath Shinde and his group's actions meant that they were disqualified under Anti-defection law, with Eknath Shinde claiming that he has not defected, but rather represents the true Shiv Sena party.[188][189] The Supreme court delivered its verdict in May 2023. In its verdict the five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme court ruled that the Maharashtra governor and assembly speaker did not act as per the law.[190] However, the court said that it cannot order the restoration of the Uddhav Thackeray government as Thackeray resigned without facing a floor test.[191][188][189] Supreme Court also asked the Assembly Speaker to decide on the matter of disqualification of 16 MLAs including Chief Minister Eknath Shinde.[192][193] The case for decision on which faction has rights to use Shiv Sena Name and Symbol is currently being heard by Supreme Court.[194][195]

In July 2023, NCP leader Ajit Pawar, and a number of NCP state assembly members joined the Shivsena- BJP government led by Eknath Shinde.[196] Sharad Pawar, the founder of NCP, has condemned the move and expelled the rebels. Ajit Pawar received support from majority of party legislators and office holders of the party.His faction was declared the official NCP and received the right to use the NCP election symbol of clock by the Election Commission of India.[197]

Economy

| Net state domestic product at factor cost at current prices (2004–05 base)[198]

Figures in crores of Indian rupees | |

| Year | Net state domestic product |

|---|---|

| 2004–2005 | ₹3.683 trillion (US$44 billion) |

| 2005–2006 | ₹4.335 trillion (US$52 billion) |

| 2006–2007 | ₹5.241 trillion (US$63 billion) |

| 2007–2008 | ₹6.140 trillion (US$74 billion) |

| 2008–2009 | ₹6.996 trillion (US$84 billion) |

| 2009–2010 | ₹8.178 trillion (US$98 billion) |

| 2013–2014 | ₹15.101 trillion (US$180 billion) |

| 2014–2015 | ₹16.866 trillion (US$200 billion) |

| 2021-2022 | ₹31.441 trillion (US$380 billion) |

| 2022-2023 | ₹36.458 trillion (US$440 billion) |

| 2023-2024 | ₹42.677 trillion (US$510 billion) |

The economy of Maharashtra is driven by manufacturing, international trade, Mass Media (television, motion pictures, video games, recorded music), aerospace, technology, petroleum, fashion, apparel, and tourism.[199] Maharashtra is the most industrialised state and has maintained the leading position in the industrial sector in India.[200] The State is a pioneer in small scale industries.[201] Mumbai, the capital of the state and the financial capital of India, houses the headquarters of most of the major corporate and financial institutions. India's main stock exchanges and capital market and commodity exchanges are located in Mumbai. The state continues to attract industrial investments from domestic as well as foreign institutions. Maharashtra has the largest proportion of taxpayers in India and its share markets transact almost 70% of the country's stocks.[202]

The service sector dominates the economy of Maharashtra, accounting for 61.4% of the value addition and 69.3% of the value of output in the state.[203] The state's per-capita income in 2014 was 40% higher than the all-India average in the same year.[204] The gross state domestic product (GSDP) at current prices for 2021–22 is estimated at $420 billion and contributes about 14.2% of the GDP. The agriculture and allied activities sector contributes 13.2% to the state's income. In 2012, Maharashtra reported a revenue surplus of ₹1524.9 million (US$24 million), with total revenue of ₹1,367,117 million (US$22 billion) and spending of ₹1,365,592.1 million (US$22 billion).[203] Maharashtra is the largest FDI destination of India. FDI inflows in the State since April 2000 to September 2021 totalled ₹9,59,746 crore, which was 28.2% of total FDI inflows at the all-India level. With a total of 11,308 startups, Maharashtra has the highest number of recognised startups in the country.

Maharashtra contributes 25% of the country's industrial output[205] and is the most indebted state in the country.[206][207] Industrial activity in state is concentrated in Seven districts: Mumbai City, Mumbai Suburban, Thane, Aurangabad, Pune, Nagpur, and Nashik.[208] Mumbai has the largest share in GSDP (19.5%), both Thane and Pune districts contribute about same in the Industry sector, Pune district contributes more in the agriculture and allied activities sector, whereas Thane district contributes more in the Services sector.[208] Nashik district shares highest in the agricultural and allied activities sector, but is behind in the Industry and Services sectors as compared to Thane and Pune districts.[208] Industries in Maharashtra include chemical and chemical products (17.6%), food and food products (16.1%), refined petroleum products (12.9%), machinery and equipment (8%), textiles (6.9%), basic metals (5.8%), motor vehicles (4.7%) and furniture (4.3%).[209] Maharashtra is the manufacturing hub for some of the largest public sector industries in India, including Hindustan Petroleum Corporation, Tata Petrodyne and Oil India Ltd.[210]

Maharashtra is the leading Indian state for many Creative industries including advertising, architecture, art, crafts, design, fashion, film, music, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software, toys and games, TV and radio, and video games.[citation needed]

Maharashtra has an above-average knowledge industry in India, with Pune Metropolitan Region being the leading IT hub in the state. Approximately 25% of the top 500 companies in the IT sector are based in Maharashtra.[211] The state accounts for 28% of the software exports of India.[211]

Maharashtra and particularly Mumbai is a prominent location for the Indian entertainment industry, with many films, television series, books, and other media being set there.[212] Mumbai is the largest centre for film and television production and a third of all Indian films are produced in the state. Multimillion-dollar Bollywood productions, with the most expensive costing up to ₹1.5 billion (US$18 million), are filmed there.[213] Marathi films used to be previously made primarily in Kolhapur, but now are produced in Mumbai.[214]

The state houses important financial institutions such as the Reserve Bank of India, the Bombay Stock Exchange, the National Stock Exchange of India, the SEBI and the corporate headquarters of numerous Indian companies and multinational corporations. It is also home to some of India's premier scientific and nuclear institutes like BARC, NPCL, IREL, TIFR, AERB, AECI, and the Department of Atomic Energy.[208]

With more than half the population being rural, agriculture and allied industries play an important role in the states's economy and source of income for the rural population.[215] The agriculture and allied activities sector contributes 12.9% to the state's income. Staples such as rice and millet are the main monsoon crops. Important cash crops include sugarcane, cotton, oilseeds, tobacco, fruit, vegetables, and spices such as turmeric.[93] Animal husbandry is an important agriculture-related activity. The State's share in the livestock and poultry population in India is about 7% and 10%, respectively. Maharashtra was a pioneer in the development of Agricultural Cooperative Societies after independence. It was an integral part of the then Governing Congress party's vision of 'rural development with local initiative'. A 'special' status was accorded to the sugar cooperatives and the government assumed the role of a mentor by acting as a stakeholder, guarantor, and regulator,[216][217][218] Apart from sugar, cooperatives play a crucial role in dairy,[219] cotton, and fertiliser industries.

The banking sector comprises scheduled and non-scheduled banks.[211] Scheduled banks are of two types, commercial and cooperative. Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs) in India are classified into five types: State Bank of India and its associates, nationalised banks, private sector banks, Regional Rural Banks, and others (foreign banks). In 2012, there were 9,053 banking offices in the state, of which about 26% were in rural and 54% were in urban areas. Maharashtra has a microfinance system, which refers to small-scale financial services extended to the poor in both rural and urban areas. It covers a variety of financial instruments, such as lending, savings, life insurance, and crop insurance.[220] The three largest urban cooperative banks in India are all based in Maharashtra.[221]

Transport

The state has a large, multi-modal transportation system with the largest road network in India.[222] In 2011, the total length of surface road in Maharashtra was 267,452 km (166,187 mi);[223] national highways accounted for 4,176 km (2,595 mi),[224] and state highways 3,700 km (2,300 mi).[223] The Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation (MSRTC) provides economical and reliable passenger road transport service in the public sector.[225] These buses, popularly called ST (State Transport), are the preferred mode of transport for much of the populace. Hired forms of transport include metered taxis and auto-rickshaws, which often ply specific routes in cities. Other district roads and village roads provide villages, accessibility to meet their social needs as well as the means to transport agricultural produce from villages to nearby markets. Major district roads provide a secondary function of linking between main roads and rural roads. Approximately 98% of villages are connected either via the highways or modern roads in Maharashtra. Average speed on state highways varies between 50–60 km/h (31–37 mph) due to the heavy presence of vehicles; in villages and towns, speeds are as low as 25–30 km/h (16–19 mph).[226]

The first passenger train in India ran from Mumbai to Thane on 16 April 1853.[227] Rail transportation is run by the Central Railway, Western Railway, South Central Railway, and South East Central Railway zones of the Indian Railways with the first two zones being headquartered in Mumbai, at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CSMT) and Churchgate respectively. Konkan Railway is headquartered in Navi Mumbai.[228][229] The Mumbai Rajdhani Express, the fastest Rajdhani train, connects the Indian capital of New Delhi to Mumbai.[230] Thane and CSMT are the busiest railway stations in India,[231] the latter serving as a terminal for both long-distance trains and commuter trains of the Mumbai Suburban Railway.

The two principal seaports, Mumbai Port and Jawaharlal Nehru Port, which is also in the Mumbai region, are under the control and supervision of the government of India.[232] There are around 48 minor ports in Maharashtra.[233] Most of these handle passenger traffic and have a limited capacity. None of the major rivers in Maharashtra are navigable, and thus river transport does not exist in the state.[citation needed]

Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport (formerly Bombay International Airport), is the state's largest airport. The four other international airports are Pune International Airport, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport at Nagpur, Nashik Airport, Shirdi Airport. Aurangabad Airport, Kolhapur Airport, Jalgaon Airport, and Nanded Airport are domestic airports in the state. Most of the State's airfields are operated by the Airports Authority of India (AAI) while Reliance Airport Developers (RADPL), currently operates five non-metro airports at Latur, Nanded, Baramati, Osmanabad and Yavatmal on a 95-year lease.[234] The Maharashtra Airport Development Company (MADC) was set up in 2002 to take up development of airports in the state that are not under the AAI or the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC). MADC is playing the lead role in the planning and implementation of the Multi-modal International Cargo Hub and Airport at Nagpur (MIHAN) project.[235] Additional smaller airports include Akola, Amravati, Chandrapur, Ratnagiri, and Solapur.[236] Maharashtra Metro Rail Corporation Limited (Maha Metro), headquartered in Nagpur is a Joint Venture establishment of Government of India & Government of Maharashtra headquartered in Nagpur, India. Maha Metro is responsible for the implementation of all Maharashtra state metro projects, except the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Mumbai Metro is operational since 8 June 2014.[citation needed]

Education

Census of 2011 showed literacy rates in the state for males and females were around 88.38% and 75.87% respectively.[237]

Regions that comprise the present day state of Maharashtra have been known for their pioneering role in the development of the modern education system in India. Scottish missionary John Wilson, American Marathi mission, Indian nationalists such as Vasudev Balwant Phadke and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, social reformers such as Jyotirao Phule, Dhondo Keshav Karve and Bhaurao Patil played a leading role in the setting up of modern schools and colleges during the British colonial era.[238][239][240][241] The forerunner of Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute was established in 1821. The Shreemati Nathibai Damodar Thackersey Women's University, the oldest women's liberal arts college in South Asia, started its journey in 1916. College of Engineering Pune, established in 1854, is the third oldest college in Asia.[242] Government Polytechnic Nagpur, established in 1914, is one of the oldest polytechnics in India.[243] Most of the private colleges including religious and special-purpose institutions were set up in the last thirty years after the State Government of Vasantdada Patil liberalised the Education Sector in 1982.[244]

Primary and secondary level education

Schools in the state are either managed by the government or by private trusts, including religious institutions.The medium of instruction in most of the schools is mainly Marathi, English, or Hindi, though Urdu is also used. The secondary schools are affiliated with the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), the National Institute of Open School (NIOS), and the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education. Under the 10+2+3 plan, after completing secondary school, students typically enroll for two years in a junior college, also known as pre-university, or in schools with a higher secondary facility affiliated with the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education or any central board. Students choose from one of three streams, namely liberal arts, commerce, or science. Upon completing the required coursework, students may enrol in general or professional degree programs.[citation needed]

Tertiary education

Maharashtra has 24 universities with a turnout of 160,000 Graduates every year.[245][246] Established during the rule of East India company in 1857 as Bombay University, The University of Mumbai, is the largest university in the world in terms of the number of graduates.[247] It has 141 affiliated colleges.[248] According to a report published by The Times Education magazine, 5 to 7 Maharashtra colleges and universities are ranked among the top 20 in India.[249][250][251] Maharashtra is also home to notable autonomous institutes as Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Indian Institute of Information Technology Pune, College of Engineering Pune (CoEP), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological University, Institute of Chemical Technology, Homi Bhabha National Institute, Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli, and Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), Sardar Patel College of Engineering (SPCE).[252] Most of these autonomous institutes are ranked the highest in India and have very competitive entry requirements. The University of Pune (now Savitribai Phule Pune University), the National Defence Academy, Film and Television Institute of India, Armed Forces Medical College, and National Chemical Laboratory were established in Pune soon after the Indian independence in 1947. Mumbai has an IIT, has National Institute of Industrial Engineering and Nagpur has IIM and AIIMS. Other notable institutes in the state are: Maharashtra National Law University, Nagpur (MNLUN), Maharashtra National Law University, Mumbai (MNLUM), Maharashtra National Law University, Aurangabad (MNLUA), Government Law College, Mumbai (GLC), ILS Law College, and Symbiosis Law School (SLS)[citation needed]

Agricultural universities include Vasantrao Naik Marathwada Agricultural University, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Dr. Panjabrao Deshmukh Krishi Vidyapeeth, and Dr. Balasaheb Sawant Konkan Krishi Vidyapeeth,[253] Regional universities viz. Sant Gadge Baba Amravati University, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, North Maharashtra University, Shivaji University, Solapur University, Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University, and Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University are established to cover the educational needs at the district levels of the state. deemed universities are established in Maharashtra, including Symbiosis International University, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and Tilak Maharashtra University.[254]

Vocational training in different trades such as construction, plumbing, welding, automobile mechanics is offered by post-secondary school Industrial Training Institute (ITIs).[255] Local community colleges also exist with generally more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition.[256]

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Health indicators of Maharashtra show that they have attained relatively high growth against a background of high per capita income (PCI).[257] In 2011, the health care system in Maharashtra consisted of 363 rural government hospitals,[258] 23 district hospitals (with 7,561 beds), 4 general hospitals (with 714 beds) mostly under the Maharashtra Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and 380 private medical establishments; these establishments provide the state with more than 30,000 hospital beds.[259] It is the first state in India to have nine women's hospitals serving 1,365 beds.[259] The state also has a significant number of medical practitioners who hold the Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery qualifications. These practitioners primarily use the traditional Indian therapy of Ayurveda, nevertheless, modern western medicine is used as well.[260]

In Maharashtra as well as in the rest of India, Primary Health Centre (PHC) is part of the government-funded public health system and is the most basic unit of the healthcare system. They are essentially single-physician clinics usually with facilities for minor surgeries, too.[261] Maharashtra has a life expectancy at birth of 67.2 years in 2011, ranking it third among 29 Indian states.[262] The total fertility rate of the state is 1.9.[263] The Infant mortality rate is 28 and the maternal mortality ratio is 104 (2012–2013), which are lower than the national averages.[264][265] Public health services are governed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), through various departments. The Ministry is divided into two departments: the Public Health Department, which includes family welfare and medical relief, and the Department of Medical Education and Drugs.[266][267]

Health insurance includes any program that helps pay for medical expenses, through privately purchased insurance, social insurance, or a social welfare program funded by the government.[268] In a more technical sense, the term is used to describe any form of insurance that protects against the costs of medical services.[269] This usage includes private insurance and social insurance programs such as National Health Mission, which pools resources and spreads the financial risk associated with major medical expenses across the entire population to protect everyone, as well as social welfare programs such as National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and the Health Insurance Program, which assist people who cannot afford health coverage.[268][269][270]

Energy

Although its population makes Maharashtra one of the country's largest energy users,[271][272] conservation mandates, mild weather in the largest population centres, and strong environmental movements have kept its per capita energy use to one of the smallest of any Indian state.[273] The high electricity demand of the state constitutes 13% of the total installed electricity generation capacity in India, which is derived mainly from fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas.[274] Mahavitaran is responsible for the distribution of electricity throughout the state by buying power from Mahanirmiti, captive power plants, other state electricity boards, and private sector power generation companies.[273]

As of 2012[update], Maharashtra was the largest power generating state in India, with an installed electricity generation capacity of 26,838 MW.[272] The state forms a major constituent of the western grid of India, which now comes under the North, East, West and North Eastern (NEWNE) grids of India.[271] Maharashtra Power Generation Company (MAHAGENCO) operates thermal power plants.[275] In addition to the state government-owned power generation plants, there are privately owned power generation plants that transmit power through the Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Company, which is responsible for the transmission of electricity in the state.[276]

Environmental protection and sustainability

Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) is established and responsible for implementing various environmental legislations in the state principally including the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, Water (Cess) Act, 1977 and some of the provisions under Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 and the rules framed there under it including, Biomedical Waste (M&H) Rules, 1998, Hazardous Waste (M&H) Rules, 2000, and Municipal Solid Waste Rules, 2000. MPCB is functioning under the administrative control of the Environment Department of the Government of Maharashtra.[277] The Maharashtra Plastic and Thermocol Products ban became effective as law on 23 June 2018, subjecting plastic users to fines and potential imprisonment for repeat offenders.[278][279]

Culture

Cuisine

Maharashtrian cuisine includes a variety of dishes ranging from mild to very spicy ones. Wheat, rice, jowar, bajri, vegetables, lentils and fruit form staple food of the Maharashtrian diet. Some of the popular traditional dishes include puran poli, ukdiche modak, Thalipeeth.[280] Street food items like Batata wada, Misal Pav, Pav Bhaji and Vada pav are very popular among the locals and are usually sold on stalls and in small hotels.[281] Meals (mainly lunch and dinner) are served on a plate called thali. Each food item served on the thali is arranged in a specific way. All non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes are eaten with boiled rice, chapatis or with bhakris, made of jowar, bajra or rice flours. A typical vegetarian thali is made of chapati or bhakri (Indian flat bread), dal, rice (varan bhaat), amti, bhaji or usal, chutney, koshimbir (salad) and buttermilk or Sol kadhi. A bhaji is a vegetable dish made of a particular vegetable or combination of vegetables. Aamti is variant of the curry, typically consisting of a lentil (tur) stock, flavoured with goda masala and sometimes with tamarind or amshul, and jaggery (gul).[281][282] Varan is nothing but plain dal, a common Indian lentil stew. More or less, most of the dishes use coconut, onion, garlic, ginger, red chili powder, green chilies, and mustard though some section of the population traditionally avoid onion and garlics.[283][281]

Maharashtrian cuisine varies with the regions. Traditional Malvani (Konkani), Kolhapuri, and Varhadhi dishes are examples of well known regional cuisines.[283] Kolhapur is famous for Tambda Pandhra rassa, a dish made of either chicken or mutton.[284] Rice and seafood are the staple foods of the coastal Konkani people. Among seafood, the most popular is a fish variety called the Bombay duck (also known as bombil in Marathi).[citation needed]

Attire

Traditionally, Marathi women commonly wore the sari, often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs.[285] Most middle-aged and young women in urban Maharashtra dress in western outfits such as skirts and trousers or shalwar kameez with the traditionally nauvari or nine-yard lugade,[286] disappearing from the markets due to a lack of demand.[287] Older women wear the five-yard sari. In urban areas, the five-yard sari, especially the Paithani, is worn by younger women for special occasions such as marriages and religious ceremonies.[288] Among men, western dressing has greater acceptance. Men also wear traditional costumes such as the dhoti, and pheta[289] on cultural occasions. The Gandhi cap is the popular headgear among older men in rural Maharashtra.[285][290][291] Women wear traditional jewellery derived from Maratha and Peshwa dynasties. Kolhapuri saaj, a special type of necklace, is also worn by Marathi women.[285] In urban areas, western attire is dominant amongst women and men.[291]

Music

Maharashtra and Maharashtrian artists have been influential in preserving and developing Hindustani classical music for more than a century. Notable practitioners of Kirana or Gwalior style called Maharashtra their home. The Sawai Gandharva Bhimsen Festival in Pune started by Bhimsen Joshi in the 1950s is considered the most prestigious Hindustani music festival in India, if not one of the largest.[292]

Cities like Kolhapur and Pune have been playing a major role in the preservation of music like Bhavageet and Natya Sangeet, which are inherited from Indian classical music. The biggest form of Indian popular music is songs from films produced in Mumbai. Film music, in 2009 made up 72% of the music sales in India.[293] Many the influential music composers and singers have called Mumbai their home.[citation needed]

In recent decades, the music scene in Maharashtra, and particularly in Mumbai has seen a growth of newer music forms such as rap.[294] The city also holds festivals in western music genres such as blues.[295] In 2006, the Symphony Orchestra of India was founded, housed at the NCPA in Mumbai. It is today the only professional symphony orchestra in India and presents two concert seasons per year, with world-renowned conductors and soloists.[citation needed]

Maharashtra has a long and rich tradition of folk music. Some of the most common forms of folk music in practice are Bhajan, Bharud, Kirtan, Gondhal,[296] and Koli Geet.[297]

Dance

Marathi dance forms draw from folk traditions. Lavani is popular form of dance in the state. The Bhajan, Kirtan and Abhangas of the Warkari sect (Vaishanav Devotees) have a long history and are part of their daily rituals.[298][299] Koli dance (called 'Koligeete') is among the most popular dances of Maharashtra. As the name suggests, it is related to the fisher folk of Maharashtra, who are called Koli. Popular for their unique identity and liveliness, their dances represent their occupation. This type of dance is represented by both men and women. While dancing, they are divided into groups of two. These fishermen display the movements of waves and casting of the nets during their koli dance performances.[300][301]

Theatre

Modern Theatre in Maharashtra can trace its origins to the British colonial era in the middle of the 19th century. It is modelled mainly after the western tradition but also includes forms like Sangeet Natak (musical drama). In recent decades, Marathi Tamasha has also been incorporated in some experimental plays.[302] The repertoire of Marathi theatre ranges from humorous social plays, farces, historical plays, and musical, to experimental plays and serious drama. Marathi Playwrights such as Vijay Tendulkar, Purushottam Laxman Deshpande, Mahesh Elkunchwar, Ratnakar Matkari, and Satish Alekar have influenced theatre throughout India.[303] Besides Marathi theatre, Maharashtra and particularly, Mumbai, has had a long tradition of theatre in other languages such as Gujarati, Hindi, and English.[304]

The National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCP) is a multi-venue, multi-purpose cultural centre in Mumbai which hosts events in music, dance, theatre, film, literature, and photography from India as well other places. It also presents new and innovative work in the performing arts field.[citation needed]

Literature

Maharashtra's regional literature is about the lives and circumstances of Marathi people in specific parts of the state. The Marathi language, which boasts a rich literary heritage, is written in the Devanagari script.[305] The earliest instance of Marathi literature is Dnyaneshwari, a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita by 13th-century Bhakti Saint Dnyaneshwar and devotional poems called abhangs by his contemporaries such as Namdev, and Gora Kumbhar. Devotional literature from the Early modern period includes compositions in praise of the God Pandurang by Bhakti saints such as Tukaram, Eknath, and Rama by Ramdas respectively.[306][307]

19th century Marathi literature includes mainly Polemic works of social and political activists such as Balshastri Jambhekar, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Hari Deshmukh, Mahadev Govind Ranade, Jyotirao Phule, and Vishnushastri Krushnashastri Chiplunkar. Keshavasuta was a pioneer in modern Marathi poetry. The Hindutva proponent, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was a prolific writer. His work in English and Marathi consists of many essays, two novels, poetry, and plays.

Four Marathi writers have been honoured with the Jnanpith Award, India's highest literary award. They include novelists, Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar, and Bhalchandra Nemade, Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar (Kusumagraj) and Vinda Karandikar. The last two were known for their poetry as well.[308] Other notable writers from the early and mid 20th century include playwright Ram Ganesh Gadkari, novelist Hari Narayan Apte, poet, and novelist B. S. Mardhekar, Pandurang Sadashiv Sane, Vyankatesh Madgulkar, Pralhad Keshav Atre, Chintamani Tryambak Khanolkar, and Lakshman Shastri Joshi. Vishwas Patil, Ranjit Desai, and Shivaji Sawant are known for novels based on Maratha history. P. L. Deshpande gained popularity in the period after independence for depicting the urban middle class society. His work includes humour, travelogues, plays, and biographies.[309] Narayan Gangaram Surve, Shanta Shelke, Durga Bhagwat, Suresh Bhat, and Narendra Jadhav are some of the more recent authors.

Dalit literature originally emerged in the Marathi language as a literary response to the everyday oppressions of caste in mid-twentieth-century independent India, critiquing caste practices by experimenting with various literary forms.[310] In 1958, the term "Dalit literature" was used for the first conference of Maharashtra Dalit Sahitya Sangha (Maharashtra Dalit Literature Society) in Mumbai.[311]

Maharashtra, and particularly the cities in the state such as Mumbai and Pune are diverse with different languages being spoken. Mumbai is called home by writers in English such as Rohinton Mistry, Shobha De, and Salman Rushdie. Their novels are set with Mumbai as the backdrop.[312] Many eminent Urdu poets such as Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Gulzar, and Javed Akhtar have been residents of Mumbai.

Cinema

Maharashtra is a prominent location for the Indian entertainment industry, with enormous films, television series, books, and other media production companies being set there.[316] Mumbai has numerous film production studios and facilities to produce films.[317] Mainstream Hindi films are popular in Maharashtra, especially in urban areas. Mumbai is the largest centre for film and television production and a third of all Indian films are produced in the state. Multimillion-dollar Bollywood productions, with the most expensive costing up to ₹1.5 billion (US$18 million), are filmed there.[318]

The first Indian feature-length film, Raja Harishchandra, was made in Maharashtra by Dadasaheb Phalke in 1913.[319] Phalke is widely considered the father of Indian cinema.[320] The Dadasaheb Phalke Award is India's highest award in cinema, given annually by the Government of India for lifetime contribution to Indian cinema.[321]

The Marathi film industry, initially located in Kolhapur, has spread throughout Mumbai. Well known for its art films, the early Marathi film industry included acclaimed directors such as Dadasaheb Phalke, V. Shantaram, Raja Thakur, Bhalji Pendharkar, Pralhad Keshav Atre, Baburao Painter, and Dada Kondke. Some of the directors who made acclaimed films in Marathi are Jabbar Patel, Mahesh Manjrekar, Amol Palekar, and Sanjay Surkar.

Durga Khote was one of the first women from respectable families to enter the film industry, thus breaking a social taboo.[322] Lalita Pawar, Sulabha Deshpande, and Usha Kiran featured in Hindi and Marathi movies. In 70s and 80s, Smita Patil, Ranjana Deshmukh, Reema Lagoo featured in both art and mainstream movies in Hindi and Marathi. Rohini Hattangadi starred in a number of acclaimed movies, and is the only Indian actress to win the BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role for her performance as Kasturba Gandhi in Gandhi (1982).[323] Bhanu Athaiya was the first Indian to win an Oscar in Best Costume Design category for Gandhi (1982).[324][325] In 90s and 2000s, Urmila Matondkar and Madhuri Dixit starred in critically acclaimed and high grossing films in Hindi and Marathi.[citation needed]

In earliest days of Marathi cinema, Suryakant Mandhare was a leading star.[326] In later years, Shriram Lagoo, Nilu Phule, Vikram Gokhale, Dilip Prabhavalkar played character roles in theatre, and Hindi and Marathi films. Ramesh Deo and Mohan Joshi played leading men in Mainstream Marathi movies.[327][328] In 70s and 80s, Sachin Pilgaonkar, Ashok Saraf, Laxmikant Berde and Mahesh Kothare created a "comedy film wave" in Marathi Cinema.[citation needed]

Media