Veganism

| Veganism | |

|---|---|

| Description | Elimination of the use of animal products |

| Early proponents | Roger Crab (1621–1680) James Pierrepont Greaves (1777–1842) Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) Donald Watson (1910–2005) H. Jay Dinshah (1933–2000) |

| Origin of the term | 1 November 1944, with the foundation of the British Vegan Society |

| Notable vegans | |

| List of vegans | |

Veganism ([[WP:IPA for English|/ˈviːgənɪzəm/]]) is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal products, particularly in diet, as well as an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of sentient animals. A follower of veganism is known as a vegan.

Distinctions are sometimes made between different categories of veganism. Dietary vegans (or strict vegetarians) refrain from consuming animal products, not only meat and fish but, in contrast to ovo-lacto vegetarians, also eggs, dairy products and other animal-derived substances. The term ethical vegan is often applied to those who not only follow a vegan diet, but extend the vegan philosophy into other areas of their lives, and oppose the use of animals or animal products for any purpose.[1] Another term used is environmental veganism, which refers to the rejection of animal products on the premise that the harvesting or industrial farming of animals is environmentally damaging and unsustainable.[2]

The term vegan was coined in England in 1944 by Donald Watson, co-founder of the British Vegan Society, to mean "non-dairy vegetarian"; the society also opposed the consumption of eggs. In 1951 the society extended the definition of veganism to mean "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals," and in 1960 H. Jay Dinshah started the American Vegan Society, linking veganism to the Jain concept of ahimsa, the avoidance of violence against living things.[3]

Veganism is a small but growing movement. In many countries the number of vegan restaurants is increasing, and some of the top athletes in certain endurance sports – for instance, the Ironman triathlon and the ultramarathon – practise veganism, including raw veganism.[4] Well-planned vegan diets have been found to offer protection against certain degenerative conditions, including heart disease,[5] and are regarded by the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada as appropriate for all stages of the life-cycle.[6] Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fibre, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals, and lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[7] Because uncontaminated plant foods do not provide vitamin B12 (which is produced by microorganisms such as bacteria), researchers agree that vegans should eat foods fortified with B12 or take a daily supplement (see below).[8]

History

19th century: Spread of vegetarianism

The International Vegetarian Union (IVU) defines vegetarianism as "a diet of foods derived from plants, with or without dairy products, eggs and/or honey"; the British Vegetarian Society adds that vegetarians avoid the by-products of slaughter.[10] The word vegetarian came into use in the early 19th century to refer to those who avoided meat; The Oxford English Dictionary attributes the earliest known use of the word to the English actress Fanny Kemble (1809–1893), writing in Georgia in the United States in 1839.[9] Rod Preece writes that it is clear from the early references that the word was already in widespread use.[11]

Those who also avoided fish, eggs and dairy products were known as strict or total vegetarians.[12] There were several attempts in the 19th century to establish strict-vegetarian communities. In 1834 Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888), the American transcendentalist and strict vegetarian – and father of the novelist Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888) – opened the Temple School in Boston, Massachusetts, to promote his ideas, and in England in 1838 James Pierrepont Greaves (1777–1842) opened Alcott House in Ham, Surrey, a community and school that followed a strict-vegetarian diet.[13] In 1844 Alcott founded Fruitlands, a strict-vegetarian community in Harvard, Massachusetts, though it lasted only seven months.[14]

Members of Alcott House – along with the ovo-lacto vegetarian Bible Christian Church and readers of the Truth-Tester temperance journal – were involved in 1847 in forming the British Vegetarian Society.[15] In 1886 the society published an influential essay, A Plea for Vegetarianism, by the English campaigner Henry Salt (1851–1939), one of the first writers to make the paradigm shift from animal welfare to animal rights.[16] In the essay Salt wrote that being a vegetarian was a "formidable admission" to make, because "a Vegetarian is still regarded, in ordinary society, as little better than a madman."[17]

Early 20th century: Shift toward veganism

In 1851 an article appeared in the Vegetarian Society's magazine about alternatives to leather for shoes, which the IVU cites as evidence of the existence in England of a group who were not only strict vegetarians, but who avoided animal products entirely.[18] In 1910 the first known British vegan cookbook, No Animal Food: Two Essays and 100 Recipes by Rupert H. Wheldon, was published in London by C.W. Daniel.[19]

In a study of the origins of veganism in the UK, historian Leah Leneman (1944–1999) wrote that there was a vigorous correspondence between 1909 and 1912 among members of the Vegetarian Society about the issue of dairy products and eggs.[20] One reader wrote: "You cannot have eggs without also having on your hands a number of male birds, which you must kill."[21] C.P. Newcombe, the editor of TVMHR, the journal of the society's Manchester branch, started a debate about it in 1912 on the letters page, to which 24 vegetarians responded. He summarized their views: "The defence of the use of eggs and milk by vegetarians, so far as it has been offered here, is not satisfactory. The only true way is to live on cereals, pulse, fruit, nuts and vegetables." The journal wrote in 1923 that the "ideal position for vegetarians is abstinence from animal products," and that most of the society's members were in a transitional stage.[22]

In November 1931 Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) addressed a meeting in London of the Vegetarian Society – attended by around 500 members, including Henry Salt – arguing that it ought to promote a meat-free diet as a moral issue, not as an issue of human health. Gandhi had become friends with Salt and other vegetarian campaigners, including the human-rights campaigner Annie Besant (1847–1933), the novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), and the physician Anna Kingsford (1846–1888), author of The Perfect Way in Diet (1881). His speech was called "The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism"; Norm Phelps writes that it was a rebuke to members who had focused on its health benefits.[23]

Gandhi told the society he had found in his student days in London that vegetarians talked of nothing but food and disease: "I feel that this is the worst way of going about the business. I notice also that it is those persons who become vegetarians because they are suffering from some disease or other – that is, from purely the health point of view – it is those persons who largely fall back. I discovered that for remaining staunch to vegetarianism a man requires a moral basis." Gandhi himself had been persuaded by doctors and relatives to drink goat's milk after refusing cow's milk because of the way the cows and calves are treated; he told the society it was the tragedy of his life that, as he saw it, he needed animal milk to regain strength after an illness. Nevertheless, Phelps argues that the speech was a call to the society to align itself with Salt's views on animal rights, and a precursor to the ideas of Donald Watson in 1944.[24]

1944: Coining the term vegan

The dairy/eggs conundrum within the Vegetarian Society remained unresolved; in 1935 the society's journal wrote that the issue was becoming more pressing with every year.[22] In July 1943 Leslie Cross, a member of the Leicester Vegetarian Society, expressed concern in its newsletter, The Vegetarian Messenger, that vegetarians were still eating dairy products.[25] He echoed the argument about eggs, that to produce milk for human consumption the cow has to be separated from her calves soon after their birth: "in order to produce a dairy cow, heart-rending cruelty, and not merely exploitation, is a necessity."[26] Cross was later a founder of the Plant Milk Society, now known as Plamil Foods, which in 1965 began production of the first widely distributed soy milk.[27]

In August 1944 two of the Vegetarian Society's members, Donald Watson (1910–2005) and Elsie "Sally" Shrigley (died 1978), suggested forming a subgroup of non-dairy vegetarians. When the executive committee rejected the idea, they and five others met on 1 November that year at the Attic Club in Holborn, London, to discuss setting up a separate organization.[28] They suggested several terms to replace non-dairy vegetarian, including dairyban, vitan, benevore, sanivore and beaumangeur. Watson decided on vegan, pronounced veegun (/ˈviːɡən/), with the stress on the first syllable. As he put it in 2004, the word consisted of the first three and last two letters of vegetarian, "the beginning and end of vegetarian." He called the new group the Vegan Society.[29]

Joanne Stepaniak writes that two vegan books appeared in 1946: the Leicester Vegetarian Society published Vegetarian Recipes without Dairy Produce by Margaret B. Rawls in the spring, and that summer the Vegan Society published Vegan Recipes by Fay K. Henderson.[30] In 1951 the Vegan Society broadened its definition of veganism to "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals," and pledged to "seek to end the use of animals by man for food, commodities, work, hunting, vivisection and all other uses involving exploitation of animal life by man."[31] Leslie Cross, by then the society's vice-president, wrote:

"[V]eganism is not so much welfare as liberation, for the creatures and for the mind and heart of man; not so much an effort to make the present relationship bearable, as an uncompromising recognition that because it is in the main one of master and slave, it has to be abolished before something better and finer can be built.[31]

The first vegan society in the United States was founded in 1948 by a nurse and chiropractor, Catherine Nimmo (1887–1985) of Oceano, California, and Rubin Abramowitz of Los Angeles. Originally from the Netherlands, Nimmo had been a vegan since 1931, and when the British Vegan Society was founded she began distributing its newsletter, The Vegan News, to her mailing list within the United States.[32] In 1957 H. Jay Dinshah (1933–2000), the son of a Parsi from Mumbai, visited a slaughterhouse and read some of Watson's literature. He gave up all animal products, and on 8 February 1960 founded the American Vegan Society (AVS) in Malaga, New Jersey. He incorporated Nimmo's society and explicitly linked veganism to the concept of ahimsa, a Sanskrit word meaning "non-harming." The AVS called the idea "dynamic harmlessness," and named its magazine Ahimsa.[33] In 1962, according to Stepaniak, the word vegan was first independently published in the Oxford Illustrated Dictionary, defined as "a vegetarian who eats no butter, eggs, cheese or milk."[34] Since 1994 World Vegan Day has been held every 1 November, the founding date of the British Vegan Society in 1944.[35]

Demographics

Surveys in the United States suggest that between 0.5 and three percent (one to six million) in that country are vegan. In 1996 three percent said they did not use animals for any purpose, a 2006 Harris Interactive poll suggested that 1.4 percent were dietary vegans, a 2008 survey for the Vegetarian Resource Group (VRG) reported 0.5 percent, a 2009 VRG survey said one percent – two million out of a population of 313 million, or one in 150 – and a 2012 Gallup poll reported two percent.[36]

In Europe, The Times estimated in 2005 that there were 250,000 vegans in the UK, in 2006 The Independent estimated 600,000, and in 2007 a British government survey identified two percent as vegan.[37] The Netherlands Association for Veganism estimated there were 16,000 vegans in the Netherlands as of 2007, around 0.1 percent of the population.[38] The first Vegetarian Butcher shop – selling vegan and vegetarian "mock meats" – opened in the Netherlands in 2010; as of September 2011 there were 30 branches in the Netherlands and Belgium.[39]

Animal products

Avoidance

Ethical vegans entirely reject the commodification of animals. The Vegan Society in the UK will only certify a product as vegan if it is free of animal involvement as far as possible and practical, including animal testing.[40]

An animal product is any material derived from animals, including meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, dairy products, honey, fur, leather, wool, and silk. Other commonly used, but perhaps less well-known, animal products are beeswax, bone char, bone china, carmine, casein, cochineal, gelatin, isinglass, lanolin, lard, rennet, shellac, tallow, whey, and yellow grease. Many of these may not be identified in the list of ingredients in the finished product.[41]

Ethical vegans will not use animal products for clothing, toiletries, or any other reason, and will try to avoid ingredients that have been tested on animals. They will not buy fur coats, cars with leather in them, leather shoes, belts, bags, wallets, woollen jumpers, silk scarves, camera film, bedding that contains goose down or duck feathers, and will not use certain vaccines; the production of the flu vaccine, for example, involves the use of chicken eggs. Depending on their economic circumstances, vegans may donate items made from animal products to charity when they become vegan, or use them until they wear out. Clothing made without animal products is widely available in stores and online. Alternatives to wool include cotton, hemp, rayon and polyester. Some vegan clothes, in particular shoes, are made of petroleum-based products, which has triggered criticism because of the environmental damage associated with production.[42]

Milk and eggs

One of the main differences between a vegan and a typical vegetarian diet is the avoidance of eggs and dairy products such as milk, cheese, butter and yogurt. Ethical vegans state that the production of eggs and dairy causes animal suffering and premature death. In battery cage and free-range egg production, most male chicks are culled at birth because they will not lay eggs; there is therefore no financial incentive for a producer to keep them.[43]

To produce milk from dairy cattle, dairy cows are kept almost permanently pregnant through artificial insemination to prolong lactation. Unwanted male calves are slaughtered at birth or sent for veal production. Female calves are separated from their mothers a few days after birth and fed milk replacer, so that the cow's milk is retained for human consumption.[44] After about five years, once the cow's milk production has dropped, they are considered "spent" and sent to slaughter for hamburger meat and their hides. A dairy cow's natural life expectancy is about twenty years.[45] The situation is similar with goats and their kids.[46]

Honey and other insect products

There is disagreement among vegan groups about the extent to which products from insects must be avoided. Some vegans view the consumption of honey as cruel and exploitative, and modern beekeeping a form of enslavement.[47] Once the honey (the bees' natural food store) is harvested, it is common practice to substitute it with sugar or corn syrup to maintain the colony over winter. Neither the Vegan Society nor the American Vegan Society considers the use of honey, silk or other insect products to be suitable for vegans, while Vegan Action and Vegan Outreach regard it as a matter of personal choice.[48] Agave nectar is a popular vegan alternative to honey.[49]

Vegan diet

Common dishes and ingredients

- Further information: Vegan recipes

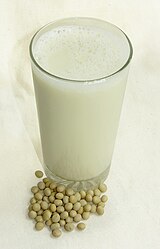

Common vegan dishes include ratatouille, falafel, hummus, veggie burritos, rice and beans, veggie stir-fry and pasta primavera. Ingredients made from soybeans are a staple of the vegan diet because soybeans are a complete protein.[50] They are consumed most often in the form of soy milk, tofu (soy milk mixed with a coagulant; it comes in a variety of textures from silken for desserts and salad dressings, to firm and extra firm for stews), tempeh and texturized vegetable protein (TVP). The wheat-based seitan/gluten is another source of plant protein. Meat analogues, or mock meats, also made of soy or gluten, are used to make vegetarian sausage, vegetarian mince and veggie burgers, and are usually entirely free of animal products.

Plant milk, ice-cream and cheese

Plant cream and plant milk – such as soy milk, almond milk, grain milk (oat milk and rice milk) and coconut milk – are used instead of cows' or goats' milk. The two most commonly used and widely available are soy and almond milk. Soy milk, like animal milk and meat, is a complete protein, meaning that it contains all the essential amino acids and can be replied upon entirely for protein intake;[50] it provides 8–11 g of protein per cup (c. 245 g). Note that soy milk alone should not be used as a replacement for breast milk for babies; babies who are not breastfed need commercial infant formula, which is normally based on cow's milk or soy.[51] Almond milk has fewer calories but less protein.[52] Popular plant-milk brands include Dean Foods' Silk soy milk and almond milk, Blue Diamond's Almond Breeze, Taste the Dream's Almond Dream and Rice Dream, Plamil Foods' Organic Soya and Alpro's Soya. Vegan ice-creams include Tofutti, Turtle Mountain's So Delicious, and Luna & Larry’s Coconut Bliss.[53] Butter can be replaced with a vegan margarine such as Earth Balance.[54]

Cheese analogues are made from soy, nuts and tapioca. Vegan cheeses like Chreese, Daiya, Sheese, Teese and Tofutti can replace both the taste and meltability of dairy cheese.[55] Nutritional yeast is a common cheese substitute in vegan recipes.[56] Cheese substitutes can be made at home, using recipes from Joanne Stepaniak's Vegan Vittles (1996), The Nutritional Yeast Cookbook (1997), and The Uncheese Cookbook (2003), and Mikoyo Schinner's Artisan Vegan Cheese (2012).[57] One recipe for vegan brie involves combining cashews, soy yogurt and coconut oil.[58]

Egg replacements

Vegan (egg-free) mayonnaise brands include Vegenaise, Nayonaise and Plamil's Egg-Free Mayo.[59] Eggs are often replaced in vegan recipes with ground flax seeds; replace each egg in a recipe with one tablespoon flaxseed meal mixed with three tablespoons of water. Commercial starch-based egg substitutes, such as Ener-G egg replacer, are also available.[60] For vegan pancakes a tablespoon of baking powder can be used instead of eggs.[61] Other ingredients used as egg replacements in recipes include silken (soft) tofu, mashed potato, apple sauce and bananas.[62]

Vegan food groups

Since 1991 the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) has recommended a no-cholesterol, low-fat vegan diet based on what they call the Four New Food Groups. This was intended to replace the Four Food Groups – meat, dairy, grains, fruits and vegetables – recommended by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) from 1956 until 1992.[64] In 1992 the USDA replaced its model with the food guide pyramid, and in 2011 with MyPlate, divided into five food groups: grains, vegetables, fruits, protein (meat, poultry, seafood, beans and peas, eggs, processed soy products, nuts and seeds) and dairy.[65] In the UK, the government recommends the eatwell plate, consisting of fruits and vegetables; potatoes, bread and other starchy foods; dairy products; meat, fish, eggs or beans for protein; and very little fat or sugar.[66]

In contrast, the four vegan food groups are fruit, legumes (peas, beans and lentils for protein), grains and vegetables. PCRM recommends three or more servings a day of fruit (including at least one that is high in vitamin C, such as citrus fruit, melon or strawberries), two or more of protein-rich legumes (such as soybeans, which can be consumed as soy milk, tofu or tempeh), five or more of whole grains (such as corn, barley, rice and wheat, in products such as bread and tortillas), and four or more of vegetables (dark-green leafy vegetables such as broccoli, and dark-yellow and orange such as carrots or sweet potatoes).[63]

Nutrients

Protein

Proteins are composed of amino acids. Mangels et al write that omnivores generally obtain a third of their protein from plant foods, and ovo-lacto vegetarians a half.[67] Vegans obtain all their protein from plant sources, and a common question is whether plant protein can supply an adequate intake of the essential amino acids, which cannot be synthesized by the human body.[68]

Sources of plant protein include legumes, such as soy beans (commonly consumed as tofu, tempeh, texturized vegetable protein, soy milk and edamame), peas, peanuts, black beans and chickpeas (often eaten as hummus); grains, such as quinoa (pronounced keenwa), brown rice, corn, barley, bulgur and wheat (often eaten as whole-wheat bread and seitan); and nuts and seeds, such as almonds, hemp and sunflower seeds.[69]

Soy beans and quinoa are known as complete proteins because they each contain all the essential amino acids.[70] Mangels et al write that consuming the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of protein (0.8 g/kg body weight) in the form of soy will meet the biologic requirement for amino acids. They add that the United States Department of Agriculture has ruled that soy protein may replace meat protein in the Federal School Lunch Program.[50]

Common combinations that contain all the essential amino acids are rice and beans, corn and beans, and hummus and whole-wheat pita. A 1994 study found that a varied intake of such sources was sufficient, and the American Dietetic Association said in 2009 that a variety of plant foods consumed over the course of a day can provide all the essential amino acids for healthy adults, which means that protein combining in the same meal may not be necessary.[71] Mangels et al write that there is little reason to advise vegans to increase their protein intake, but erring on the side of caution (taking into account the lower digestibility and poorer amino acid pattern of plant protein), they would recommend a 25 percent increase over the RDA for adults, to 1.0 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight.[72] According to a 2005 review article, studies suggest that an adequate intake of plant proteins protects against certain degenerative diseases.[68]

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is a bacterial product needed for cell division, the formation and maturation of red blood cells, the synthesis of DNA, and for normal nerve function. A B12 deficiency can lead to a number of health problems, including megaloblastic anemia and nerve damage.[73] That vegans are unable in most cases, at least in the West, to obtain vitamin B12 from a plant-based diet without consuming fortified foods or supplements is often used as an argument against veganism.[74]

Neither plants nor animals make B12; it is produced by microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi and algae. Herbivorous animals obtain it from bacteria in their rumens, either by absorbing it or by eating their own cecotrope faeces; rabbits, for example, produce and eat cecal pellets. When those animals are eaten, they become sources of B12. Plants from the ground that are not washed properly may contain B12 from bacteria in the soil, often from faeces; drinking water may also be contaminated with B12-producing bacteria, particularly in the developing world.[73] Reed Mangels of the department of nutrition at the University of Massachusetts Amherst writes that bacteria in the human digestive tract produce B12, but most of it is not absorbed and is expelled in the faeces, with tiny amounts also expelled in the urine. James Halsted, a medical researcher, reported in the 1960s that a group of villagers in Iran eating very little or no animal protein were found to have normal B12 levels because they were living with animal manure near their homes, and were eating vegetables grown in human manure (known as night soil) and not thoroughly washed. The human mouth is another source of B12, but in small amounts and possibly analogue (not biologically active).[75]

Western vegan diets are likely to be deficient in B12 because of increased hygiene. Vegans can obtain B12 by taking a supplement or by eating fortified foods, such as fortified soy milk or cereal, where it may be listed as cobalamin or cyanocobalamin.[76] B12 supplements are produced industrially through bacterial fermentation-synthesis; no animal products are involved in that process. The RDA for adults (14+ years) is 2.4 mcg (or µg) a day, rising to 2.4 and 2.6 mcg for pregnancy and lactation respectively; 0.4 mcg for 0–6 months, 0.5 mcg for 7–12 months, 0.9 mcg for 1–3 years, 1.2 mcg for 4–8 years, and 1.8 mcg for 9–13 years.[77]

There is some disagreement within the vegan community as to whether supplementation is needed; several studies of vegans who did not take supplements or eat fortified food, including in Western countries, have found no sign of B12 deficiency.[78] Mangels writes that the disagreement is caused in part because there is no gold standard for assessing B12 status, and also because there are very few studies of long-term vegans who have not used supplements or fortified foods. According to Mangels, all Western vegans not using supplements or fortified foods will probably develop a B12 deficiency, though it may take decades to appear.[79] There are reports that certain plant foods are sources of B12. Mangels writes that fermented foods such as tempeh and miso, as well as edible seaweed (such as arame, wakame, nori, and kombo), spirulina, and certain greens, grains and legumes, have been cited as B12 sources, as has rainwater. She writes that tiny amounts have been found in barley malt syrup, shiitake mushrooms, parsley and sourdough bread, and higher amounts in spirulina and nori, but these products may be sources of inactive B12.[80] The consensus within the mainstream nutrition community is that vegans and perhaps even vegetarians should eat fortified foods or use supplements.[81]

Calcium

Calcium is needed to maintain bone health, and for a number of metabolic functions, including muscle function, vascular contraction and vasodilation, nerve transmission, intracellular signalling and hormonal secretion. Ninety-nine percent of the body's calcium is stored in the bones and teeth. The RDA is 200 mg for 0–6 months, 260 mg for 7–12 months, 700 mg for 1–3 years, 1,000 mg for 4–8 years, 1,300 mg for 9–18 years, 1,000 mg for 19–50 years, 1,000 mg for 51–70 years (men) and 1,200 mg (women), and 1,200 mg for 71+ years.[82]

Vegans are advised to eat three servings per day of a high-calcium food, such as fortified soy milk, fortified tofu, almonds or hazelnuts, and to take a supplement as necessary.[6] Plant sources include broccoli, turnip and cabbage, such as Chinese cabbage (bok choi) and kale; the bioavailability of calcium in spinach is poor. Whole-wheat bread contains calcium; grains contain small amounts.[82] Because vitamin D is needed for calcium absorption, vegans should make sure they consume enough vitamin D too (see below).[83]

The EPIC-Oxford study suggested that vegans have an increased risk of bone fractures over meat eaters and vegetarians, likely because of lower dietary calcium intake, but that vegans consuming more than 525 mg/day have a risk of fractures similar to that of other groups.[84] A 2009 study of bone density found the bone mineral density (BMD) of vegans was 94 percent that of omnivores, but deemed the difference clinically insignificant. Another study in 2009 by the same researchers examined over 100 vegan post-menopausal women, and found that their diet had no adverse effect on BMD and no alteration in body composition.[85] Biochemist T. Colin Campbell suggested in The China Study (2005) that osteoporosis is linked to the consumption of animal protein; he argued that, unlike plant protein, animal protein increases the acidity of blood and tissues, which is then neutralized by calcium pulled from the bones.[86]

Vitamin D

Vitamin D (calciferol) is needed for a number of functions, including calcium absorption, enabling mineralization of bone, and bone growth. Without it bones can become thin and brittle; together with calcium it offers protection against osteoporosis.[87] Mangels writes that it may also play a role in protecting against heart disease, diabetes, colon cancer, multiple sclerosis and dementia.[88] Vitamin D is produced in the body when ultraviolet rays from the sun hit the skin; outdoor exposure is needed because UVB radiation does not penetrate glass. It is present in very few foods (mostly salmon, tuna, mackerel, cod liver oil, with small amounts in cheese, egg yolks and beef liver, and in some mushrooms).[87]

Most vegan diets contain little or no vitamin D, unless the food is fortified (such as fortified soy milk), so supplements may be needed depending on exposure to sunlight.[87] Vitamin D comes in two forms. Cholecalciferol (D3) is synthesized in the skin after exposure to the sun and may be consumed in the form of animal products; when produced industrially it is taken from lanolin in sheep's wool. Ergocalciferol (D2) is suitable for vegans; it is mostly human-made and is derived from ergosterol from yeast. Several conflicting studies have suggested that the two forms may or may not be bioequivalent.[89] According to a 2011 report by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences, the differences between D2 and D3 do not affect metabolism, both function as prohormones, and when activated exhibit identical responses in the body.[90]

Supplements should be used with caution because vitamin D can be toxic, especially in children.[91] The RDA is 10 mcg for 0–12 months, 15 mcg for 1–70 years, and 20 mcg for 70+.[87] People with little or no sun exposure may need more, perhaps up to 25 mcg daily.[92] The daily tolerable upper intake level (daily) for 9 years to adulthood is 100 mcg, according to the National Institutes of Health; for children it is 25 mcg for 0–6 months, 38 mcg for 7–12 months, 63 mcg for 1–3 years, and 75 mcg for 4–8 years.[87]

The extent to which sun exposure is sufficient to meet the body's needs will depend on the time of day, cloud and smog cover, skin melanin content, whether sunscreen is worn, and the season. According to the US National Institutes of Health, most people can obtain and store sufficient vitamin D from sunlight in the spring, summer and fall months, even in the far north. They report that some vitamin D researchers recommend 5–30 minutes of sun exposure without sunscreen between ten in the morning and three o'clock in the afternoon, at least twice a week. They also report that tanning beds emitting two to six per cent UVB radiation will have a similar effect, though using tanning beds may be inadvisable for other reasons.[87]

Iron

Vegetarian and vegan diets usually contain as much iron as animal-based diets, or more; vegan diets generally contain more iron than vegetarian ones because dairy products contain very little. There are concerns about the bioavailability of iron from plant foods, assumed by some researchers to be around 5–15 percent compared to 18 percent from a nonvegetarian diet.[93] Iron deficiency anaemia is found as often in nonvegetarians as in vegetarians, though studies have shown vegetarians' iron stores to be lower.[94]

The RDA for nonvegetarians is 11 mg for 7–12 months, 7 mg for 1–3 years, 10 mg for 4–8 years, and 8 mg for 9–13 years. The RDA then changes for men and women to 11 mg for 14–18 years (men) and 15 mg for 14–18 years (women), 8 mg for 19–50 years (men) and 18 mg for 19–50 years (women). It return to 8 mg for 51+ years (men and women).[95] Mangels writes that because of the lower bioavailability of iron from plant sources, the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences established a separate RDA for vegetarians and vegans of 14 mg for vegetarian men and postmenopausal women, and 33 mg for premenopausal women not using oral contraceptives.[96] Supplements should be used only with caution after consulting a physician, because iron can accumulate within the body and cause damage to organs; this is particularly true of anyone suffering from hemochromatosis, a relatively common condition that can remain undiagnosed. The daily tolerable upper intake level, according to the National Institutes of Health, is 40 mg for 7 months to 13 years, and 45 mg for 14+.[95]

According to the Vegetarian Resource Group, high-iron foods suitable for vegans include black-strap molasses, lentils, tofu, quinoa, kidney beans and chickpeas.[97] Tom Sanders, a nutritionist at King's College London, writes that iron absorption can be enhanced by eating a source of vitamin C along with a plant source of iron, and by avoiding coingesting anything that would inhibit absorption, such as tannin in tea.[98] Sources of vitamin C might be half a cup of cauliflower, or five fluid ounces of orange juice, consumed with a plant source of iron such as soybeans, tofu, tempeh, or black beans.[99] Some herbal teas and coffee can also inhibit iron absorption, as can spices that contain tannins (turmeric, coriander, chillies, and tamarind).[100]

Omega-3 fatty acids

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an omega-3 fatty acid, is found in leafy green vegetables and nuts, and in vegetable oils such as canola and flaxseed oil. The Adequate Intake for ALA is 1.1–1.6 g/day.[101] Vegan Outreach suggests vegans take 1/4 teaspoon of flaxseed oil (also known as linseed oil) daily, and use oils containing low amounts of omega-6 fatty acids, such as olive, canola, avocado or peanut oil.[102]

Iodine

Iodine supplementation may be necessary for vegans in countries where salt is not typically iodized, where it is iodized at low levels, or where, as in Britain and Ireland, dairy products are relied upon for iodine delivery because of low levels in the soil.[103] Iodine can be obtained from most vegan multivitamins or from regular consumption of seaweeds, such as kelp.[104] The RDA is 110 mcg (0–six months), 130 mcg (7–12 months), 90 mcg (1–8 years), 120 mcg (9–13 years), 150 mcg (14+). The RDA for pregnancy and lactation is 220 and 290 mcg respectively.[105]

Health arguments

There is growing scientific consensus that a plant-based diet reduces the risk of a number of degenerative diseases, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, kidney disease and dementia.[5] Winston Craig, chair of the department of nutrition at Andrews University, writes that vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fibre, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron and phytochemicals, and lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc and vitamin B12. He writes that vegans tend to be thinner, with lower serum cholesterol and lower blood pressure. He adds that eliminating all animal products increases the risk of nutritional deficiencies; of particular concern are vitamins B12 and D, calcium and omega-3 fatty acids. He advises vegans to eat foods fortified with these nutrients or to take supplements, and writes that iron and zinc may also be problematic because of limited bioavailability.[7]

The American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada said in 2003 that properly planned vegan diets were nutritionally adequate for all stages of life, including pregnancy and lactation. People avoiding meat are reported to have lower body mass index; from this follows lower death rates from ischemic heart disease, lower blood cholesterol levels, lower blood pressure, and fewer incidences of type 2 diabetes, prostate and colon cancers.[6] A group of prominent physicians in the United States – John A. McDougall, Caldwell Esselstyn, Neal D. Barnard, Dean Ornish and Michael Greger – together with T. Colin Campbell, professor emeritus of nutritional biochemistry, argue that diets based on animal fat and animal protein, such as the standard American diet, are detrimental to health, and that a low-fat vegan diet can not only prevent, but may even reverse, certain diseases.[106] The Swiss Federal Nutrition Commission and the German Society for Nutrition do not recommend a vegan diet, and caution against it for children, the pregnant and the elderly.[107]

Between 1980 and 1984 the Oxford Vegetarian Study recruited 11,000 subjects (6000 vegetarians and a control group of 5000 non-vegetarians) and followed up after 12 years. The study indicated that vegans had lower total- and LDL-cholesterol concentrations than the meat-eaters, and that death rates were lower in the non-meat eaters. The authors wrote that mortality from ischemic heart disease was positively associated with higher dietary cholesterol levels and the consumption of animal fat. They also wrote that the non-meat-eaters had half the risk of the meat eaters of requiring an emergency appendectomy, and that vegans in the UK may be prone to iodine deficiency.[103]

A 1999 meta-analysis of five studies comparing mortality rates in Western countries found that mortality from ischemic heart disease was 26 percent lower in vegans than in regular meat-eaters. This was compared to 20 percent lower in occasional meat eaters, 34 percent lower in pescetarians (those who ate fish but no other meat), and 34 percent lower in ovo-lacto vegetarians (those who ate no meat, but did consume animal milk and eggs). The lower rate of protection for vegans compared to pescetarians or ovo-lacto vegetarians is believed to be linked to higher levels of homocysteine, caused by insufficient vitamin B12; it is believed that vegans who consume sufficient B12 should show even lower risk of ischemic heart disease than ovo-lacto vegetarians. No significant difference in mortality was found from other causes.[108]

The American Dietetic Association indicated in 2003 that vegetarian diets may be more common among adolescents with eating disorders, but that the evidence suggests the adoption of a vegetarian diet may serve to camouflage an existing disorder, rather than causing one.[6] Other studies support this conclusion.[109]

Pregnancy, babies and children

The American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada consider well-planned vegan diets "appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including during pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood and adolescence."[110] The Swiss Federal Nutrition Commission and the German Society for Nutrition caution against a vegan diet for pregnant women and children.[107] A doctor or registered dietitian should be consulted about taking supplements during pregnancy. The American Dietetic Association writes that a regular source of B12 is crucial for pregnant, lactating and breastfeeding women.[111] According to Reed Mangels, maternal stores of B12 appear not to cross the placenta,[112] and researchers have reported cases of vitamin B12 deficiency in lactating vegetarian mothers that were linked to deficiencies and neurological disorders in their children.[113] Pregnant vegans may also need to take extra vitamin D, depending on their exposure to sunlight and whether they are eating fortified foods.[114] Doctors may recommend iron supplements and folic acid for all pregnant women (vegan, vegetarian and non-vegetarian).[115]

Newspapers have reported several cases of malnutrition in children whose parents said they were vegan. A 12-year-old girl in Scotland who had eaten no meat or dairy since birth was found in 2008 to be suffering from rickets (caused by a lack of vitamin D), and had several fractures.[116] In 2000 in London, a nine-month-old girl died after her vegan mother fed her a fruitarian diet of raw fruit and nuts.[117] In 2004 in Atlanta, a six-week-old boy died after his vegan parents appear to have fed him mostly apple juice and soy milk. The prosecution argued that the case was not about veganism, but that the child had simply not been fed. Dr. Amy Lanou, nutrition director of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, and an expert witness for the prosecution in that case, argued that vegan diets are "not only safe for babies; they're healthier than ones based on animal products," and wrote that "the real problem was that [the child] was not given enough food of any sort."[118]

Vegan toiletries

The British Vegan Society criteria for vegan certification are that the product contain no animal products, and that neither the product nor its ingredients have been tested on animals by the manufacturer, by others on behalf of the manufacturer, or by anyone over whom the manufacturer has control. The society's website contains a list of certified companies and products.[119] Beauty Without Cruelty is well-known within the vegan community as a manufacturer of vegan toiletries and cosmetics. Animal Aid in the UK sells vegan toiletries and other products online, as does Honesty Cosmetics.[120] Kiss My Face sells a range of vegan toiletries in the United States, Canada and the UK. Lush is based in a number of countries and sells products online; the company says that 83 percent of its products are vegan. Haut Minerals in Canada make a range of vegan products, including a vegan BB cream.[121] In South Africa, Esse Organic Skincare is one of several companies certified by Beauty Without Cruelty. The Choose Cruelty Free website in Australia lists vegan products available there.[122]

Because animal ingredients are cheap, they are ubiquitous in toiletries. After animals are slaughtered for meat, the leftovers (bones, brains, eyes, spines and other parts) are put through the rendering process, and some of that material, especially the fats, ends up in toiletries and cosmetics. Common animal products in toiletries include tallow in soap; glycerine (derived from collagen), used as a lubricant and humectant in haircare products, moisturizers, shaving foam, soap and toothpaste (there is a plant-based form but the glycerine in most products is probably animal-based); lanolin from sheep's wool, found in lip balm and moisturizers; and stearic acid, found in face creams, shaving foam and shampoos (as with glycerine, there is a plant-based form, but most mainstream manufacturers use the animal-derived form). Lactic acid, an alpha-hydroxy acid derived from animal milk, is another common ingredient, as is allantoin, derived from the comfrey plant or cow's urine and found in shampoos, moisturizers and toothpaste. Vegans often refer to Animal Ingredients A to Z (2004) to check which ingredients might be animal-derived.[123]

Dietary, ethical, and environmental perspectives

Vegans can be split into three categories. Dietary vegans refrain from eating or drinking anything that contains an animal product, out of concern for human health or animal welfare; they may continue to use animal products in other areas, such as clothing and toiletries. Peter Singer has used the term "flexible vegans" for this group.[124] Ethical vegans go further and see veganism as a philosophy, usually with a focus on animal rights. They reject the commodity or property status of animals, and refrain entirely from using them or products derived from them; they will not use animals for food, clothing or any other purpose.[125] Environmental vegans focus on conservation rather than animal rights: they reject the use of animal products on the premise that practices such as farming – particularly factory farming – fishing, hunting and trapping are environmentally unsustainable.[2]

Dietary veganism

The Associated Press (AP) reported in January 2011 that the vegan diet was moving from marginal to mainstream in the United States, with vegan books such as Skinny Bitch (2005) becoming best sellers, and several celebrities exploring vegan diets: "Today's vegans are urban hipsters, suburban moms, college students, even professional athletes." According to the AP, over half the 1,500 chefs polled in 2011 by the National Restaurant Association included vegan entrees in their restaurants, and chain restaurants are starting to mark vegan items on their menus.[127]

Former US president Bill Clinton adopted a vegan diet in 2010 after cardiac surgery, eating legumes, vegetables and fruit, together with a daily drink of almond milk, fruit and protein powder; his daughter Chelsea was already a vegan.[128] Oprah Winfrey followed a vegan diet for 21 days in 2008, and in 2011 asked her 378 production staff to do the same for one week.[129] In 2009 Dr. Mehmet Oz began advising his viewers to go vegan for 28 days.[130] In November 2010 Bloomberg Businessweek reported that a growing number within the business community were following a vegan diet, including William Clay Ford, Jr., Joi Ito, John Mackey, Russell Simmons, Biz Stone, Steve Wynn and Mortimer Zuckerman. The boxer Mike Tyson also announced that he had switched to a vegan diet.[131]

Ethical veganism

Philosophy

Ethical vegans see veganism as a philosophy and set of principles, not simply a diet; they often maintain that eating a vegan diet does not in itself constitute veganism. Joanne Stepaniak, author of Being Vegan and The Vegan Sourcebook (both 2000), argues that to place the qualifier "dietary" before "vegan" is akin to using the term "secular Catholic" for people who want to practise only some aspects of Catholicism.[132] Bob Torres and Jenna Torres, authors of Vegan Freak (2005), write that ethical veganism consists of "living life consciously as an anti-speciesist."[133] Carol J. Adams, the vegan-feminist writer, has used the concept of the absent referent to describe what she calls a psycho-social detachment between the consumer and the consumed. She wrote in The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990):

Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes. The 'absent referent' is that which separates the meat eater from the animal and the animal from the end product. The function of the absent referent is to keep our 'meat' separated from any idea that she or he was once an animal, to keep the 'moo' or 'cluck' or 'baa' away from the meat, to keep something from being seen as having been someone."[134]

There is a division within animal rights theory between a rights-based or deontological approach and a utilitarian one, which is reflected in the debate about the moral basis of veganism. Tom Regan, professor emeritus of philosophy at North Carolina State University, is a rights theorist who argues that animals possess inherent value as "subjects-of-a-life" – because they have beliefs and desires, an emotional life, memory, and the ability to initiate action in pursuit of goals – and must therefore be viewed as ends in themselves, not as means to an end.[135] He argues that the right of subjects-of-a-life not to be harmed can be overridden only when outweighed by other valid moral principles, but that the reasons cited for eating animal products – pleasure, convenience and the economic interests of farmers – are not weighty enough to override the animals' moral rights.[136]

Gary L. Francione, professor of law at Rutgers School of Law-Newark, is also a rights theorist. He argues that "all sentient beings should have at least one right – the right not to be treated as property," and that adopting veganism must be the unequivocal baseline for anyone who sees nonhuman animals as having intrinsic moral value. To fail to do so is like arguing for human rights while continuing to own human slaves, he writes. Francione sees no coherent difference between eating meat and eating dairy or eggs: animals used in the dairy and egg industries live longer, are treated worse and end up in the same slaughterhouses.[137] He argues that the pursuit of improved conditions for animals, rather than the abolition of animal use, is like campaigning for "conscientious rapists" who will rape their victims without beating them. The pursuit of animal welfare, he argues, does not move us away from the paradigm of animals qua property, and serves only to make people feel comfortable about using them.[138]

Peter Singer, professor of bioethics at Princeton University, approaches the issue from a utilitarian perspective. He argues that there is no moral or logical justification for refusing to count animal suffering as a consequence when making ethical decisions, and that sentience is "the only defensible boundary of concern for the interests of others."[139] He does not contend that killing animals is wrong in principle, but argues that from a consequentialist standpoint it should be rejected unless necessary for survival. He therefore advocates both veganism and improved conditions for farm animals to reduce suffering.[140]

Debate about the "Paris exemption"

Unlike Francione, Singer is not concerned about what he calls trivial infractions of vegan principles, arguing that personal purity is not the issue. He supports what is known as the "Paris exemption": if you find yourself in a fine restaurant, allow yourself to eat what you want, and if you have no access to vegan food, going vegetarian is acceptable.[141]

Singer's support for the "Paris exemption" is part of a debate within the animal rights movement about the extent to which it ought to promote veganism without exception. The positions are reflected by the divide between the animal protectionist side (represented by Singer and PETA), according to which incremental change can achieve real reform, and the abolitionist side (represented by Regan and Francione), according to which apparent welfare reform serves only to persuade the public that animal use is morally unproblematic. Singer said in 2006 that the movement should be more tolerant of people who choose to use animal products if they are careful about making sure the animals had a decent life.[142] Bruce Friedrich of PETA argued in the same year that a strict adherence to veganism can become an obsession:

[W]e all know people whose reason for not going vegan is that they "can't" give up cheese or ice cream. ... Instead of encouraging them to stop eating all other animal products besides cheese or ice cream, we preach to them about the oppression of dairy cows. Then we go on about how we don’t eat sugar or a veggie burger because of the bun, even though a tiny bit of butter flavor in a bun contributes to significantly less suffering than any non-organic fruit or vegetable does or a plastic bottle or about 100 other things that most of us use. Our fanatical obsession with ingredients not only obscures the animals’ suffering – which was virtually non-existent for that tiny modicum of ingredient – but also nearly guarantees that those around us are not going to make any change at all. So, we’ve preserved our personal purity, but we’ve hurt animals – and that’s anti-vegan.[143]

Francione writes that this position is similar to arguing that, because human rights abuses can never be eliminated entirely, we should not safeguard human rights in situations we control. By failing to ask a server whether something contains animal products, in the interest of avoiding a fuss, he argues that we reinforce the idea that the moral rights of animals are a matter of convenience. He concludes from this that the PETA/Singer position fails even on its own consequentialist terms.[144]

Environmental veganism

Resources and the environment

People who adopt veganism for environmental reasons do so because it consumes fewer resources and causes less environmental damage. One example of an environmental vegan is Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, the marine conservation direct-action group. He told The Guardian in 2010 that all Sea Shepherd ships are vegan: "Forty percent of the fish caught from the oceans is fed to livestock – pigs and chickens are becoming major aquatic predators. The livestock industry is one of the greatest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions ever. The eating of meat is an ecological disaster ... We're promoting veganism not for animal-rights reasons but for environmental conservation reasons."[146]

In November 2006 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization released Livestock's Long Shadow, a report that linked animal agriculture to environmental damage. It concluded that livestock farming (primarily of cows, chickens and pigs) has an impact on almost all aspects of the environment: air, land, soil, water, biodiversity and climate change.[147] It concluded that livestock account for 9 percent of total carbon dioxide emissions, 37 percent of methane, 65 percent of nitrous oxide, and 68 percent of ammonia; livestock waste emits 30 million tonnes of ammonia a year, which the report said is involved in the production of acid rain.[148] In June 2010 a report from the United Nations Environment Programme declared that a move toward a vegan diet is needed to save the world from hunger, fuel shortages and climate change. It said that agriculture, particularly the production of meat and dairy products, accounts for 19 percent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions, 38 percent of land use and 70 percent of freshwater consumption.[149]

Greenhouse gas emissions are not limited to animal husbandry. Plant-based sources such as rice cultivation cause similar problems.[150] A 2007 Cornell University study that simulated land use for various diets for New York State concluded that, although vegetarian diets used the smallest amount of land per capita, a low-fat diet that included some meat and dairy – less than 2 oz (57 g) of meat/eggs per day, significantly less than that consumed by the average American – could support slightly more people on the same available land than could be fed on some high-fat vegetarian diets, since animal food crops are grown on lower-quality land than are crops for human consumption.[151]

Debate over animals killed in crop harvesting

Steven Davis, a professor of animal science at Oregon State University, asked Tom Regan in 2001 what the difference was between killing a field mouse while cultivating crops, and killing a pig for the same reason, namely so that human beings could eat. Reagan responded with a utilitarian position that we must choose foods that, overall, cause the least harm to the least number of animals. Davis argued that a plant-based diet would kill more than one containing beef from grass-fed ruminants.[152] Andy Lamey, a philosopher at Monash University, calls this the "burger vegan" argument, namely that if human beings were to eat cows raised on a diet of grass, not grain, fewer animals would be killed overall, because the number of mice, rats, raccoons, and other animals killed during the harvest outnumbers the deaths involved in raising cows for beef.[153]

Based on a study finding that wood mouse populations dropped from 25 per hectare to five per hectare after harvest (attributed to migration and mortality), Davis estimated that 10 animals per hectare are killed from crop farming every year. He argued that if all 120,000,000 acres (490,000 km2) of cropland in the continental United States were used for a vegan diet, approximately 500 million animals would die each year. But if half the cropland were converted to ruminant pastureland, he estimated that only 900,000 animals would die each year – assuming people switched from the eight billion poultry killed each year to beef, lamb, and dairy products. Therefore, he argued, according to the least-harm principle we should convert to a ruminant-based diet rather than a plant-based one.[152]

Davis's analysis was criticized in 2003 by Gaverick Matheny in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. Matheny argued that Davis had miscalculated the number of animal deaths based on land area rather than per consumer, and had confined his analysis to grass-fed ruminants, rather than factory-farmed animals. He wrote that Davis had equated lives with lives worth living, focusing on numbers rather than including in his calculations the harm done to animals raised for food, which can involve pain from branding, dehorning and castration, a life of confinement, transport without food or water to a slaughterhouse, and a frightening death. Matheny argued that vegetarianism "likely allows a greater number of animals with lives worth living to exist."[154] Lamey argued that Davis's calculation of harvest-related deaths was flawed because based on two studies; one included deaths from predation, which is "morally unobjectionable" for Regan because not related to human action, and the other examined production of a nonstandard crop (sugarcane), which Lamey wrote has little relevance to deaths associated with typical crop production.[155] Lamey also maintained, like Matheny, that accidental deaths are ethically distinct from intentional ones, and that if Davis includes accidental animal deaths in the moral cost of veganism, he must also include the accidental human deaths caused by his proposed diet, which, Lamey wrote, leaves "Davis, rather than Regan, with the less plausible argument." [156]

See also

Notes

- ^ For the ethical/dietary distinction, see for example:

- "Vegan Diets Become More Popular, More Mainstream", Associated Press/CBS News, 5 January 2011: "Ethical vegans have a moral aversion to harming animals for human consumption ... though the term often is used to describe people who follow the diet, not the larger philosophy."

- Francione, Gary and Garner, Robert. The Animal Rights Debate: Abolition Or Regulation? Columbia University Press, 2010 (hereafter Francione and Garner 2010), p. 62: "Although veganism may represent a matter of diet or lifestyle for some, ethical veganism is a profound moral and political commitment to abolition on the individual level and extends not only to matters of food but also to the wearing or using of animal products. Ethical veganism is the personal rejection of the commodity status of nonhuman animals ..."

- "Veganism", Vegetarian Times, January 1989: "Webster's dictionary provides a most dry and limiting definition of the word 'vegan': 'one that consumes no animal food or dairy products.' This description explains dietary veganism, but so-called ethical vegans – and they are the majority – carry the philosophy further."

- ^ a b Cole, Matthew. "Veganism," in Margaret Puskar-Pasewicz. Cultural Encyclopedia of Vegetarianism. ABC-Clio, 2010, p. 241.

- For an example of an environmental vegan, see Shapiro, Michael. "Sea Shepherd's Paul Watson: 'You don't watch whales die and hold signs and do nothing'", The Guardian, 21 September 2010 (hereafter Shapiro 2010).

- For environmental veganism, also see Torres, Bob and Torres, Jenna. Vegan Freak: Being Vegan in a Non-Vegan World. PM Press, 2005 (hereafter Torres and Torres 2005), pp. 100–102.

- ^ Berry, Ryan. "Veganism," The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 604–605.

- For the origins of the term "vegan," see "Interview with Donald Watson", Vegetarians in Paradise, 11 August 2004: "I invited my early readers to suggest a more concise word to replace "non-dairy vegetarian." Some bizarre suggestions were made like "dairyban, vitan, benevore, sanivore, beaumangeur", et cetera. I settled for my own word, "vegan", containing the first three and last two letters of "vegetarian" – "the beginning and end of vegetarian." The word was accepted by the Oxford English Dictionary and no one has tried to improve it."

- Watson, Donald. Vegan News, No. 1, November 1944: "We should all consider carefully what our Group, and our magazine, and ourselves, shall be called. 'Non-dairy' has become established as a generally understood colloquialism, but like 'non-lacto' it is too negative. Moreover, it does not imply that we are opposed to the use of eggs as food."

- For the Vegan Society extending its definition of "veganism" in 1951, see Cross, Leslie. "Veganism Defined", The Vegetarian World Forum, 5(1), Spring 1951.

- ^ Berry 2007, pp. 604–605:

- "Despite the seeming hardships a vegan diet imposes on its practitioners, veganism is a burgeoning movement, especially among younger Americans. In the endurance sports, such as the Ironman triathlon and the Utramarathon, the top competitors are vegans who consume much of their vegan food in its uncooked state. Even young weight lifters and body builders are gravitating to a vegan diet, giving the lie to the notion that eating animal flesh is essential for strength and stamina. Brendan Brazier, a young athlete who regularly places in the top three in international triathlon events and who formulated Vega, a line of plant-based performance products, said of his fellow vegan athletes: 'We're beginning to build a strong presence in every sport.'"

- For more about its popularity, see "Vegan Diets Become More Popular, More Mainstream", Associated Press, 5 January 2011.

- Also see Nijjar, Raman. "From pro athletes to CEOs and doughnut cravers, the rise of the vegan diet", CBC News, 4 June 2011.

- For other examples of Ironman triathlon athletes who are vegan, see Scott, David and Heidrich, Ruth. "Vegetarian/Vegan Ironman and Ironlady", European Vegetarian Union News, issue 4, 1997.

- ^ a b Note that several sources use the word "vegetarian" to refer to an entirely plant-based diet:

- Leitzmann, C. "Vegetarian diets: what are the advantages?", Forum of Nutrition, 57, 2005, pp. 147–156 (review article): "A growing body of scientific evidence indicates that wholesome vegetarian diets offer distinct advantages compared to diets containing meat and other foods of animal origin. The benefits arise from lower intakes of saturated fat, cholesterol and animal protein as well as higher intakes of complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C and E, carotenoids and other phytochemicals. ... In most cases, vegetarian diets are beneficial in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, renal disease and dementia, as well as diverticular disease, gallstones and rheumatoid arthritis."

- Also see "Building healthy eating patterns", Dietary Guidelines for Americans, United States Department of Agriculture, 2010, p. 45: "In prospective studies of adults, compared to non-vegetarian eating patterns, vegetarian-style eating patterns have been associated with improved health outcomes – lower levels of obesity, a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, and lower total mortality. Several clinical trials have documented that vegetarian eating patterns lower blood pressure.

On average, vegetarians consume a lower proportion of calories from fat (in particular, saturated fatty acids); fewer overall calories; and more fiber, potassium, and vitamin C than do non-vegetarians. In general, vegetarians have a lower body mass index. These characteristics and other lifestyle factors associated with a vegetarian diet may contribute to the positive health outcomes that have been identified among vegetarians."

- For other review articles, see:

- Van Horn, L, et al. "The evidence for dietary prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease", Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(2), February 2008, pp. 287–331 (systematic review).

- Ströhle, A; Waldmann, A; Wolters, M; and Hahn, A. "Vegetarian nutrition: Preventive potential and possible risks. Part 1: Plant foods", Wien Klin Wochenschr, 118(19–20), October 2006, pp. 580–593 (abstract in English, article in German).

- Key T.J., Appleby P.N., and Rosell, M.S. "Health effects of vegetarian and vegan diets", Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 65(1), February 2006, pp. 35–41.

- Sabaté, J. "The contribution of vegetarian diets to health and disease: a paradigm shift?", American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3 Suppl), September 2003, pp. 502S–507S.

- Nestle, M. "Animal v. plant foods in human diets and health: is the historical record unequivocal?", Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 58(2), May 1999, pp. 211–218.

- ^ a b c d "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: vegetarian diets", Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 64(2), Summer 2003, pp. 62–81 (also available here): "Well-planned vegan and other types of vegetarian diets are appropriate for all stages of the life-cycle including during pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence."

- Craig, Winston J.; Mangels, Ann Reed; American Dietetic Association. "Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets", Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(7), July 2009, pp. 1266–1282.

- Also see:

- "A guide to vegetarian eating", Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute, accessed 3 December 2012.

- "Vegetarische Ernährung – Gesundheitliche Vor- und Nachteile", Bundesamt für Gesundheit (Switzerland), 2012.

- "Vegane Ernährung: Nährstoffversorgung und Gesundheitsrisiken im Säuglings- und Kindesalte", Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung (Germany), 11 May 2011.

- ^ a b Craig, Winston J. "Health effects of vegan diets", The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(5), May 2009, pp. 1627S–1633S (review article).

- ^ Mangels, Reed; Messina, Virginia; and Messina, Mark. The Dietitian's Guide to Vegetarian Diets. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011 (hereafter Mangels, Messina and Messina 2011), pp. 181–192.

- Mangels, Reed. "Vitamin B12 in the Vegan Diet", Vegetarian Resource Group, accessed 17 December 2012: "Vitamin B12 is needed for cell division and blood formation. Neither plants nor animals make vitamin B12. Bacteria are responsible for producing vitamin B12. Animals get their vitamin B12 from eating foods contaminated with vitamin B12 and then the animal becomes a source of vitamin B12. Plant foods do not contain vitamin B12 except when they are contaminated by microorganisms or have vitamin B12 added to them. Thus, vegans need to look to fortified foods or supplements to get vitamin B12 in their diet."

- Herbert, Victor. "Vitamin B12: plant sources, requirements and assay", American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 48(3), September 1988, pp. 852–858.

- "Vitamin B12", Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health, accessed 17 December 2012.

- Norris, Jack. "Vitamin B12: Are you getting it?", Vegan Outreach, 26 July 2006: "Contrary to the many rumors, there are no reliable, unfortified plant sources of vitamin B12 ... [There is an] overwhelming consensus in the mainstream nutrition community, as well as among vegan health professionals, that vitamin B12 fortified foods or supplements are necessary for the optimal health of vegans, and even vegetarians in many cases. Luckily, vitamin B12 is made by bacteria such that it does not need to be obtained from animal products."

- ^ a b Kemble, Fanny. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839. Harper and Brothers, New York, 1839, pp. 197–198: "The sight and smell of raw meat are especially odious to me, and I have often thought that if I had had to be my own cook, I should inevitably become a vegetarian, probably, indeed, return entirely to my green and salad days."

- Also see Davis, John. "The earliest known uses of the word 'vegetarian'", and "Extracts from some journals 1842–48 – the earliest known uses of the word 'vegetarian'", International Vegetarian Union, accessed 17 December 2012.

- Another early use of "vegetarian" is the April 1842 edition of The Healthian, a journal published by Alcott House: "Tell a healthy vegetarian that his diet is very uncongenial to the wants of his nature." See Preece, Rod. Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought. University of British Columbia Press, 2008 (hereafter Preece 2008), p. 12.

- Also see Davis, John. "Prototype Vegans", The Vegan, Winter 2010, p. 19.

- ^ "About IVU", International Vegetarian Union, accessed 17 December 2012.

- "What is a vegetarian?", Vegetarian Society, accessed 17 December 2012.

- ^ Preece 2008, pp. 12–13.

- ^ For a 19th-century reference to the vegetarian/strict vegetarian division, see "Under Examination", The Dietetic Reformer and Vegetarian Messenger, Vol XI, 1884, p. 237: "There are two kinds of Vegetarians – an extreme sect, who eat no animal food whatever; and a less extreme sect, who do not object to eggs, milk, or fish ... The Vegetarian Society ... belongs to the more moderate division."

- ^ For the Temple School, see Iacobbo, Karen and Iacobbo, Michael. Vegetarians And Vegans in America Today. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006, p. 142.

- For Alcott House, see Davis, John. World Veganism. International Vegetarian Union, 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Hart, James D. "Alcott, Amos Bronson," in The Oxford Companion to American Literature. Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 14.

- ^ Twigg, Julia. "The Vegetarian Movement in England: 1847–1981", PhD thesis, London School of Economics, 1981.

- The society held its first meeting, chaired by Salford MP Joseph Brotherton (1783–1857), in September that year at Northwood Villa in Ramsgate, Kent. See Davis, John. "The Origins of the "Vegetarians", International Vegetarian Union", 28 July 2011.

- Also see "History of the Vegetarian Society", Vegetarian Society, accessed 7 February 2011.

- ^ For Salt being the first modern animal rights advocate, see Taylor, Angus. Animals and Ethics. Broadview Press, 2003, p. 62.

- ^ Salt, Henry Stephens. A Plea for Vegetarianism and other essays, The Vegetarian Society, 1886, p. 7.

- For Salt's book on animal rights, see Salt, Henry Stephens. Animals’ Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress. Macmillan & Co, 1894.

- Also see Salt, Henry Stephens. "The Humanities of Diet," in Kerry S. Walters and Lisa Portmess. Ethical Vegetarianism: from Pythagoras to Peter Singer. State University of New York Press, 1999, p. 115ff, an extract from Salt's The Logic of Vegetarianism (1899).

- ^ "History of Vegetarianism: The Origin of Some Words", International Vegetarian Union, 6 April 2010: "... as early as 1851 there was an article in the Vegetarian Society magazine (copies still exist) about alternatives to leather for making shoes, there was even a report of someone patenting a new material. So there was always another group who were not just 'strict vegetarians' but also avoided using animal products for clothing or other purposes – naturally they wanted their own 'word' too, but they had a long wait."

- ^ Leneman, Leah. "No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909–1944",Society and Animals, 7(3), 1999, pp. 219–228 (hereafter Leneman 1999); p. 220 for Wheldon.

- In the book, Wheldon argued that "it is obvious that, since we should live as to give the greatest possible happiness to all beings capable of appreciating it and as it is an indisputable fact that animals can suffer pain, and that men who slaughter animals needlessly suffer from atrophy of all finer feelings, we should therefore cause no unnecessary suffering in the animal world." See Wheldon, Rupert. No Animal Food, Health Culture Co, New York-Passaic, New Jersey, 1910, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Leneman 1999, pp. 219, 220.

- ^ Leneman 1999, p. 222.

- ^ a b Leneman 1999, p. 221.

- ^ a b For the speech and the title, see Davis, John. "Gandhi – and the launching of veganism", International Vegetarian Union, accessed 16 December 2012.

- For Gandhi's friendship with other vegetarian campaigners, and that the speech was a rebuke to the society, see Phelps, Norm. The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA. Lantern Books, 2007 (hereafter Phelps 2007), pp. 164–165.

- For Kingsford's book, see Kingsford, Anna. The Perfect Way in Diet. Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co, 1881.

- ^ For quote from Gandhi's speech, see Phelps 2007, p. 165.

- For Gandhi's refusal to drink cow's milk, being persuaded to drink goat's milk, and "tragedy of my life," see Reid, Marion. The Vegan, Spring 1948 IV(1), pp. 4–5.

- For the speech itself, see Gandhi, Mahatma. "The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism", speech to the Vegetarian Society, London, 20 November 1931, pp. 11–14; for "tragedy of my life," see p. 13.

- ^ Stepaniak, Joanne. The Vegan Sourcebook. Lowell House, 2000 (hereafter Stepaniak 2000(a)), p. 1.

- ^ Leneman 1999, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Maher, Harry. "The Milk of Human Kindness", interview with Arthur Ling, Vegan Views, 37, Autumn 1986.

- "C Arthur Ling, 1919–2005", Plamil Foods.

- ^ Stepaniak 2000(a), pp. 1–2.

- ^ For the other terms and the Watson quote, see "Interview with Donald Watson", Vegetarians in Paradise, 11 August 2004.

- For the pronunciation, see "FAQ, Definitions", International Vegetarian Union, accessed 16 December 2012.

- For the first Vegan News, see Watson, Donald. The Vegan News, No. 1, November 1944.

- For more details, see Shrigley, Elsie. "History", The Vegan Magazine, 1962, courtesy of the Vegan Society, accessed 16 December 2012.

- For Watson's death, see "Vegan Community Mourns Donald Watson", Vegetarians in Paradise, 1 December 2005.

- ^ Stepaniak 2000(a), p. 5.

- ^ a b Cross, Leslie. "Veganism Defined", The Vegetarian World Forum, 5(1), Spring 1951: "In a vegan world the creatures would be reintegrated within the balance and sanity of nature as she is in herself. A great and historic wrong, whose effect upon the course of evolution must have been stupendous, would be righted. The idea that his fellow creatures might be used by man for self-interested purposes would be so alien to human thought as to be almost unthinkable. In this light, veganism is not so much welfare as liberation, for the creatures and for the mind and heart of man; not so much an effort to make the present relationship bearable, as an uncompromising recognition that because it is in the main one of master and slave, it has to be abolished before something better and finer can be built."

- The Vegan Society wrote in 1979 that the word veganism "denotes a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude – as far as is possible and practical – all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives ..." See "Memorandum of Association of the Vegan Society", Vegan Society, 20 November 1979.

- ^ For Nimmo's dates and background, see Austin, Linda and Hammond, Norm. Oceano. Arcadia Publishing, 2010, p. 39.

- For Nimmo's early vegan society, see Dinshah, Freya. "Vegan, More than a Dream", American Vegan, Summer 2010, p. 31.

- That Nimmo had been a vegan since 1931, see Stepaniak 2000(a), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Stepaniak 2000(a), pp. 6–7; Phelps 2007, p. 187.

- "American Vegan Society: History", American Vegan Society, accessed 17 December 2012.

- Two key books explained the vegan philosophy: Dinshah's Out of the Jungle: The Way of Dynamic Harmlessness (1965), and Victoria Moran's Compassion, the Ultimate Ethic: An Exploration of Veganism (1985). See Phelps 2007, p. 188.

- ^ Stepaniak 2000(a), p. 3.

- ^ "World Vegan Day", Vegan Society, accessed 13 August 2009.

- ^ For three percent in 1996, see Duda, Mark Damian and Young, Kira C. "Americans' attitudes toward animal rights, animal welfare, and the use of animals," 1996 (cited in Damian and Young, "American Attitudes Toward Scientific Wildlife Management ...", p. 10; also cited in Barbara McDonald. "Once You Know Something, You Can't Not Know It: An Empirical Look at Becoming Vegan", Animals and Society, 8(1), 2000, p. 3.

- For 2006, see Stahler, Charles. "How many adults are vegetarian?", Vegetarian Journal, 25, 2006, pp. 14–15.

- For 2008, see "Vegetarianism in America", Vegetarian Times, 2008.

- For 2009, see "Vegan diets becoming more popular, more mainstream", Associated Press, 6 January 2011. For one in 150, see Banerji, Robin. "Vegan dating: Finding love without meat or dairy", BBC News, 15 August 2012.

- For 2012, see "In U.S., 5% Consider Themselves Vegetarians. Even smaller 2% say they are vegans", Gallup, 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Donald Watson", The Times, 8 December 2005.

- Hickman, Martin. "An ethical diet: The joy of being vegan", The Independent, 15 March 2006.

- "Would you describe yourself as a vegetarian or vegan?", Survey of Public Attitudes and Behaviours toward the Environment, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2007, table 210, question F7, p. 481: 81 respondents out of 3,618 said they were vegans.

- ^ "Wat is veganisme?", Nederlandse Vereniging voor Veganisme, accessed 16 December 2012.

- ^ Valraven, Michael. "Vegetarian butchers make a killing", Radio Netherlands Worldwide, 14 September 2011.

- The Vegetarian Butcher, accessed 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Criteria for Vegan food", and "Trademark Standards", Vegan Society, accessed 17 December 2012.

- Also see "What is Vegan?", American Vegan Society, accessed 17 December 2012: "Vegans exclude flesh, fish, fowl, dairy products (animal milk, butter, cheese, yogurt, etc.), eggs, honey, animal gelatin, and all other foods of animal origin. Veganism also excludes animal products such as leather, wool, fur, and silk in clothing, upholstery, etc. Vegans usually make efforts to avoid the less-than-obvious animal oils, secretions, etc., in many products such as soaps, cosmetics, toiletries, household goods and other common commodities."

- ^ "Animal ingredients and products", Vegan Peace, accessed 17 December 2012.

- Meeker D.L. Essential Rendering: All About The Animal By-Products Industry. National Renderers Association, 2006.

- Also see "Vegan FAQs", Vegan Outreach, accessed 17 December 2012.

- The detailed reasons vegans may not use a specific animal product are varied. In the case of wool, for example, Merino sheep have been bred to have wrinkly skin and extra-thick wool that can lead to heat exhaustion in summer and maggot infestations, which leads to the practice of mulesing. See Chase, Heather. Beauty without the Beasts. Lantern Books, 2001, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Stepaniak 2000(a), pp. 20, 115–118, 154; see p. 116 for the environmental damage associated with petroleum-based products.

- ^ "Egg Production & Welfare", Vegetarian Society, accessed 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Dairy Cows & Welfare", Vegetarian Society, accessed 17 December 2012.