Diphenhydramine: Difference between revisions

→Mechanism of action: Changed H1 receptor Mode of Action from "Antagonist" to "Inverse Agonist" because antihistamines are the example given on Receptor antagonist for Inverse Agonists. |

→Mechanism of action: Only, now with the links fixed. (Oh, hey, TIL wikipedia links are case sensitive.) |

||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

! Biological target !! Mode of action !! Effect |

! Biological target !! Mode of action !! Effect |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[histamine H1 receptor|H<sub>1</sub> receptor]] <br> (Peripheral) || [[Inverse |

| [[histamine H1 receptor|H<sub>1</sub> receptor]] <br> (Peripheral) || [[Inverse agonist]] || Allergy reduction |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| H<sub>1</sub> receptor <br> (Central) || [[Inverse |

| H<sub>1</sub> receptor <br> (Central) || [[Inverse agonist]] || Sedation |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Muscarinic receptor|mAChR Receptors]] || [[Competitive antagonist]] || [[Anticholinergic syndrome|Anticholinergic]]<br/> [[Antiparkinson]] |

| [[Muscarinic receptor|mAChR Receptors]] || [[Competitive antagonist]] || [[Anticholinergic syndrome|Anticholinergic]]<br/> [[Antiparkinson]] |

||

Revision as of 21:51, 3 April 2016

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Benadryl, Unisom, Sominex, ZzzQuil |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682539 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Very low |

| Routes of administration | Oral, IM, IV, topical and suppository |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40–60%[1] |

| Protein binding | 98–99% |

| Metabolism | Various cytochrome P450 liver enzymes: CYP2D6 (80%), 3A4 (10%)[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 7 hours (children)[2] 12 hours (adults)[2] 17 hours (elderly)[2] |

| Excretion | 94% through the urine, 6% through feces[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.360 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

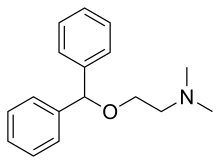

| Formula | C17H21NO |

| Molar mass | 255.355 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Diphenhydramine (/ˌdaɪfɛnˈhaɪdrəmiːn/; abbreviated DPH, sometimes DHM) is a first-generation antihistamine possessing anticholinergic, antitussive, antiemetic, and sedative properties that is mainly used to treat allergies. It is also used in the management of drug-induced parkinsonism and other extrapyramidal symptoms. The drug has a strong hypnotic effect and is FDA-approved as a nonprescription sleep aid, especially in the form of diphenhydramine citrate. It is produced and marketed under the trade name Benadryl by McNeil Consumer Healthcare in the U.S., Canada, and South Africa (trade names in other countries include Dimedrol, Daedalon, and Nytol). It is also available as a generic or store brand medication.

Diphenhydramine was one of the first antihistamines developed in early 1940s and is the prototype of the ethanolamine class of first-generation antihistamines, which also includes orphenadrine, phenyltoloxamine, dimenhydrinate, carbinoxamine, clemastine, doxylamine, and halogenated diphenhydramine derivatives. Diphenhydramine and its close structural and chemical relatives generally do not exhibit the type of stereospecificity which is seen with the alkyamine antihistamines (pheniramine (Naphcon), chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton), dexchlorpheniramine (Polaramine), brompheniramine (Dimetapp), dexbrompheniramine (Drixoral), and racemic iodopheniramine (research chemical).[5]

Diphenhydramine was first synthesized by George Rieveschl and first made publicly available through prescription in 1946.[6]

Medical uses

Diphenhydramine is a first-generation antihistamine used to treat a number of conditions including allergic symptoms and itchiness, the common cold, insomnia, motion sickness, and extrapyramidal symptoms.[7][8] Diphenhydramine also has local anesthetic properties, and has been used as such in people allergic to common local anesthetics such as lidocaine.[9]

Allergies

Diphenhydramine has been found to have a higher efficacy in treatment of allergies than some second-generation antihistamines (such as desloratadine)[10] but a similar efficacy with others (such as cetirizine).[11]

Injectable diphenhydramine is typically used in addition to epinephrine for anaphylaxis.[12] Its use for this purpose has not been properly studied.[13]

Also, topical formulations of diphenhydramine are available, including creams, lotions, gels, and sprays. These are used to relieve itching, and have the advantage of causing fewer systemic effects (e.g., drowsiness) than oral forms.[14]

Movement disorders

Diphenhydramine is used to treat Parkinson's disease-like extrapyramidal symptoms caused by antipsychotics.[15]

Sleep

Because of these sedative properties, diphenhydramine is widely used in nonprescription sleep aids for insomnia. The drug is an ingredient in several products sold as sleep aids, either alone or in combination with other ingredients such as acetaminophen (paracetamol). An example of the latter is Tylenol PM. Tolerance against the sedating effect of diphenhydramine builds very quickly; after three days of use at the common dosage, it is no more effective than a placebo[16] (according to one study done with 15 subjects). Diphenhydramine can cause minor psychological dependence.[17] Diphenhydramine can cause sedation and has also been used as an anxiolytic.[18]

Vomiting

Diphenhydramine also has antiemetic properties, which make it useful in treating the nausea that occurs in motion sickness.[19]

Adverse effects

Diphenhydramine is a potent anticholinergic agent. This activity is responsible for the side effects of dry mouth and throat, increased heart rate, pupil dilation, urinary retention, constipation, and, at high doses, hallucinations or delirium. Other side effects include motor impairment (ataxia), flushed skin, blurred vision at nearpoint owing to lack of accommodation (cycloplegia), abnormal sensitivity to bright light (photophobia), sedation, difficulty concentrating, short-term memory loss, visual disturbances, irregular breathing, dizziness, irritability, itchy skin, confusion, increased body temperature (in general, in the hands and/or feet), temporary erectile dysfunction, and excitability, and although it can be used to treat nausea, higher doses may cause vomiting.[20] Some side effects, such as twitching, may be delayed until the drowsiness begins to cease and the person is in more of an awakening mode. It has been implicated in the occasional development of restless leg syndrome.[21]

Acute poisoning can be fatal, leading to cardiovascular collapse and death in 2–18 hours, and in general is treated using a symptomatic and supportive approach.[22] Diagnosis of toxicity is based on history and clinical presentation, and in general specific levels are not useful.[23] Several levels of evidence strongly indicate diphenhydramine (similar to chlorpheniramine) can block the delayed rectifier potassium channel and, as a consequence, prolong the QT interval, leading to cardiac arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes.[24] No specific antidote for diphenhydramine toxicity is known, but the anticholinergic syndrome has been treated with physostigmine for severe delirium or tachycardia.[23] Benzodiazepines may be administered to decrease the likelihood of psychosis, agitation, and seizures in patients who are prone to these symptoms.[25]

Some patients have an allergic reaction to diphenhydramine in the form of hives.[26][27] However, restlessness or akathisia can also be a side effect made worse by increased levels of diphenhydramine, especially with recreational dosages.[28] As diphenhydramine is extensively metabolized by the liver, caution should be exercised when giving the drug to individuals with hepatic impairment.

Cumulative anticholinergic use is associated with an increased risk for dementia.[29][30]

Special populations

Diphenhydramine is not recommended for patients older than 60 or children under the age of six, unless a physician is consulted.[31] These populations should be treated with second-generation antihistamines such as loratadine, desloratadine, fexofenadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, and azelastine.[22] Due to its strong anticholinergic effects, diphenhydramine is on the "Beers list" of drugs to avoid in the elderly.[32][33]

Diphenhydramine is category B in the FDA Classification of Drug Safety During Pregnancy.[34] It is also excreted in breast milk.[35] Paradoxical reactions to diphenhydramine have been documented, in particular among children, and it may cause excitation instead of sedation.[28]

Topical diphenhydramine is sometimes used especially on patients in hospice. This use is without indication and topical diphenhydramine should not be used as treatment for nausea because research does not indicate this therapy is more effective than alternatives.[36]

Measurement in body fluids

Diphenhydramine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum.[37] Gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) can be used with electron ionization on full scan mode as a screening test. GC-MS or GC-NDP can be used for quantification.[37] Rapid urine drug screens using immunoassays based on the principle of competitive binding may show false-positive methadone results for patients having ingested diphenhydramine.[38] Quantification can be used to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest, or assist in a death investigation.[37]

Mechanism of action

| Biological target | Mode of action | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| H1 receptor (Peripheral) |

Inverse agonist | Allergy reduction |

| H1 receptor (Central) |

Inverse agonist | Sedation |

| mAChR Receptors | Competitive antagonist | Anticholinergic Antiparkinson |

| Na channel | Blocker | Local anesthetic |

| SERT | Inhibitor | Mood alteration |

Diphenhydramine is an inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.[39] It is a member of the ethanolamine class of antihistaminergic agents.[22] By reversing the effects of histamine on the capillaries, it can reduce the intensity of allergic symptoms. It also crosses the blood–brain barrier and antagonizes the H1 receptors centrally. Its effects on central H1 receptors cause drowsiness.[40]

Like many other first-generation antihistamines, diphenhydramine is also a potent antimuscarinic (a competitive antagonist of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors) and, as such, at high doses can cause anticholinergic syndrome.[41] The utility of diphenhydramine as an antiparkinson agent is the result of its blocking properties on the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.

Diphenhydramine also acts as an intracellular sodium channel blocker, which is responsible for its actions as a local anesthetic.[42] Diphenhydramine has also been shown to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin.[43] It has been shown to be a potentiator of analgesia induced by morphine, but not by endogenous opioids, in rats.[44]

Pharmacokinetics

Oral bioavailability of diphenhydramine is in the range of 40–60% and peak plasma concentration occurs about 2–3 hours after administration.[1] The primary route of metabolism is two successive demethylations of the tertiary amine. The resulting primary amine is further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.[1] The half-life is as short as 8 hours in children to 17 hours in the elderly.[2]

History

Diphenhydramine was discovered in 1943 by George Rieveschl, a former professor at the University of Cincinnati.[45][46] In 1946, it became the first prescription antihistamine approved by the U.S. FDA.[47]

In the 1960s, diphenhydramine was found to inhibit reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin.[43] This discovery led to a search for viable antidepressants with similar structures and fewer side effects, culminating in the invention of fluoxetine (Prozac), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).[43][48] A similar search had previously led to the synthesis of the first SSRI, zimelidine, from brompheniramine, also an antihistamine.[49]

Society and culture

Diphenhydramine is sometimes used recreationally as a deliriant, or as a potentiator of alcohol,[50][51] opiates,[52] DXM and other depressants. Diphenhydramine is deemed to have limited abuse potential in the United States due to its potentially serious side-effect profile and limited euphoric effects, and is not a controlled substance. Since 2002, the U.S. FDA has required special labeling warning against use of multiple products that contain diphenhydramine.[53] In some jurisdictions, diphenhydramine is often present in postmortem specimens collected during investigation of sudden infant deaths; the drug may play a role in these events.[54][55]

Diphenhydramine is among prohibited and controlled substances in the Republic of Zambia,[56] and travelers are advised not to bring the drug into the country. Several Americans have been detained by the Zambian Drug Enforcement Commission for possession of Benadryl and other over-the-counter medications containing diphenhydramine.[57]

Recreational use

Diphenhydramine is sometimes used as a recreational drug, often by those without access to illegal drugs.[58] It is used for its sedative properties and (at higher doses) delirium-induced hallucinations. In many people, it can produce a distinctive weak to moderate euphoria due to a rise in the dopamine:acetylcholine ratio in the CNS[citation needed]. A fourth use, perhaps the most common, and one which is used clinically, is to intensify the effects of opioids and to make supplies last longer by lowering opioid requirements for a given targeted objective. Recreational use of diphenhydramine may cause:[59]

- Dysphoria

- Hallucinations (auditory, visual, etc.)

- Heart palpitations

- Extreme drowsiness

- Severe dizziness

- Abnormal speech (inaudibility, forced speech, etc.)

- Flushed skin

- Severe mouth and throat dryness

- Tremors

- Seizures

- Inability to urinate

- Vomiting

- Motor disturbances

- Anxiety/nervousness

- Disorientation

- Abdominal pain

- Delirium

- Coma

- Death

See also

References

- ^ a b c Paton DM, Webster DR (1985). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of H1-receptor antagonists (the antihistamines)". Clin. Pharmacokinet. 10 (6): 477–97. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510060-00002. PMID 2866055.

- ^ a b c d Simons KJ, Watson WT, Martin TJ, Chen XY, Simons FE (July 1990). "Diphenhydramine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in elderly adults, young adults, and children". J. Clin. Pharmacol. 30 (7): 665–71. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01871.x. PMID 2391399.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Garnett WR (February 1986). "Diphenhydramine". Am. Pharm. NS26 (2): 35–40. PMID 3962845.

- ^ "Showing Diphenhydramine (DB01075)". DrugBank. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Inside Narcotics, pp 774-790

- ^ Ohio History central: Benadryl; accessed Jan. 5, 2011

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride Monograph". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

- ^ Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freudenreich O (December 2012). "How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient" (PDF). Current Psychiatary. 11 (12): 10–16.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith DW, Peterson MR, DeBerard SC (August 1999). "Local anesthesia. Topical application, local infiltration, and field block". Postgrad. Med. 106 (2): 57–60, 64–6. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.08.650. PMID 10456039.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raphael GD, Angello JT, Wu MM, Druce HM (April 2006). "Efficacy of diphenhydramine vs desloratadine and placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe seasonal allergic rhinitis". Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 96 (4): 606–14. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63557-0. PMID 16680933.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Comparison of Cetirizine to Diphenhydramine in the Treatment of Acute Food Allergic Reactions".

- ^ Young WF (2011). "Chapter 11: Shock". In Roger L. Humphries RL, Stone CK (ed.). CURRENT Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency Medicine,. LANGE CURRENT Series (Seventh ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-170107-9.

- ^ Sheikh, A; ten Broek, Vm; Brown, SG; Simons, FE (24 January 2007). "H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis with and without shock". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD006160. PMID 17253584.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Diphenhydramine Topical

- ^ Aminoff MJ (2012). "Chapter 28. Pharmacologic Management of Parkinsonism & Other Movement Disorders". In Katzung B, Masters S, Trevor A (ed.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (12th ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 483–500. ISBN 978-0-07-176401-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Richardson GS, Roehrs TA, Rosenthal L, Koshorek G, Roth T (October 2002). "Tolerance to daytime sedative effects of H1 antihistamines". J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 22 (5): 511–5. doi:10.1097/00004714-200210000-00012. PMID 12352276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kristi Monson; Arthur Schoenstadt (8 September 2013). "Benadryl Addiction". eMedTV.

- ^ Dinndorf PA, McCabe MA, Frierdich S (August 1998). "Risk of abuse of diphenhydramine in children and adolescents with chronic illnesses". J. Pediatr. 133 (2): 293–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70240-9. PMID 9709726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zachary Flake; Robert Scalley; Austin Bailey (1 March 2004). "Practical Selection of Antiemetics". American Family Physician. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Side Effects". Drugs.com. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ "Treating a Restless Legs Sydnrome (RLS)". Consumer Reports. 2011.

- ^ a b c Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollmann B (2011). "Chapter 32. Histamine, Bradykinin, and Their Antagonists". In Brunton L (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12e ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 242–245. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Manning B (2012). "Chapter 18. Antihistamines". In Olson K (ed.). Poisoning & Drug Overdose (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-166833-0. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Block of potassium currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes and lengthening of cardiac repolarization in man by the histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine".

- ^ "Wide complex tachycardia in a pediatric diphenhydramine overdose treated with sodium bicarbonate". Publisher Medical. Pediatr Emerg Care. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Heine A (November 1996). "Diphenhydramine: a forgotten allergen?". Contact Derm. 35 (5): 311–2. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02402.x. PMID 9007386.

- ^ Coskey RJ (February 1983). "Contact dermatitis caused by diphenhydramine hydrochloride". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 8 (2): 204–6. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(83)70024-1. PMID 6219138.

- ^ a b de Leon J, Nikoloff DM (February 2008). "Paradoxical excitation on diphenhydramine may be associated with being a CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer: three case reports". CNS Spectr. 13 (2): 133–5. PMID 18227744.

- ^ Gray SL; Anderson ML; Dublin S; et al. (1 March 2015). "Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: A prospective cohort study". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (3): 401–407. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. ISSN 2168-6106. PMC 4358759. PMID 25621434.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help) - ^ "Anticholinergic drug use and risk for dementia: target for dementia prevention". doi:10.1007/s00406-010-0156-4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Medical Economics (2000). Physicians' Desk Reference for Nonprescription Drugs and Dietary Supplements, 2000 (21st ed.). Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company. ISBN 1-56363-341-8.

- ^ "High risk medications as specified by NCQA's HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly" (pdf). National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).

- ^ "2012 AGS Beers List" (PDF). The American Geriatrics Society. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Black RA, Hill DA (June 2003). "Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy". Am. Fam. Physician. 67 (12): 2517–24. PMID 12825840.

- ^ Spencer JP, Gonzalez LS, Barnhart DJ (July 2001). "Medications in the breast-feeding mother". Am. Fam. Physician. 64 (1): 119–26. PMID 11456429.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, retrieved 1 August 2013, which cites

- Smith TJ, Ritter JK, Poklis JL, Fletcher D, Coyne PJ, Dodson P, Parker G (2012). "ABH Gel is Not Absorbed from the Skin of Normal Volunteers". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (5): 961–966. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.017. PMID 22560361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weschules DJ (2005). "Tolerability of the Compound ABHR in Hospice Patients". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 8 (6): 1135–1143. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1135. PMID 16351526.

- Smith TJ, Ritter JK, Poklis JL, Fletcher D, Coyne PJ, Dodson P, Parker G (2012). "ABH Gel is Not Absorbed from the Skin of Normal Volunteers". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (5): 961–966. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.017. PMID 22560361.

- ^ a b c Pragst F (2007). "Chapter 13: High performance liquid chromatography in forensic toxicological analysis". In Smith RK, Bogusz MJ (ed.). Forensic Science (Handbook of Analytical Separations). Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-444-52214-6.

- ^ Rogers SC, Pruitt CW, Crouch DJ, Caravati EM (September 2010). "Rapid urine drug screens: diphenhydramine and methadone cross-reactivity". Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 26 (9): 665–6. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181f05443. PMID 20838187.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khilnani and Khilnani (October 2011). "Inverse agonism and its therapeutic significance". Indian J Pharmacol. 43 (5): 492–501. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.84947. PMID 3195115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Reiner PB, Kamondi A (April 1994). "Mechanisms of antihistamine-induced sedation in the human brain: H1 receptor activation reduces a background leakage potassium current". Neuroscience. 59 (3): 579–88. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(94)90178-3. PMID 8008209.

- ^ Lopez AM (10 May 2010). "Antihistamine Toxicity". Medscape Reference. WebMD LLC.

- ^ Kim YS, Shin YK, Lee C, Song J (October 2000). "Block of sodium currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons by diphenhydramine". Brain Research. 881 (2): 190–8. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02860-2. PMID 11036158.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Domino EF (1999). "History of modern psychopharmacology: a personal view with an emphasis on antidepressants". Psychosom. Med. 61 (5): 591–8. doi:10.1097/00006842-199909000-00002. PMID 10511010.

- ^ Carr KD, Hiller JM, Simon EJ (February 1985). "Diphenhydramine potentiates narcotic but not endogenous opioid analgesia". Neuropeptides. 5 (4–6): 411–4. doi:10.1016/0143-4179(85)90041-1. PMID 2860599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hevesi D (29 September 2007). "George Rieveschl, 91, Allergy Reliever, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ "Benadryl". Ohio History Central. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Ritchie J (24 September 2007). "UC prof, Benadryl inventor dies". Business Courier of Cincinnati. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ Awdishn RAL, Whitmill M, Coba V, Killu K (October 2008). "Serotonin reuptake inhibition by diphenhydramine and concomitant linezolid use can result in serotonin syndrome". Chest. 134 (4 Meeting abstracts). doi:10.1378/chest.134.4_MeetingAbstracts.c4002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barondes SH (2003). Better Than Prozac. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-19-515130-5.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine and Alcohol / Food Interactions". Drugs.com.

- ^ Zimatkin SM, Anichtchik OV (1999). "Alcohol-histamine interactions". Alcohol Alcohol. 34 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/34.2.141. PMID 10344773.

- ^ Sandor I (30 July 2000). "Using Antihistamines, Anticholinergics, and Depressants To Potentiate Opiates, And Dealing With Opiate Side Effects". Antihistamine Aficionado Magazine.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration, HHS (2002). "Labeling of Diphenhydramine-Containing Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use". Federal Register. 67 (235): 72555–9. PMID 12474879. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ Marinetti L, Lehman L, Casto B, Harshbarger K, Kubiczek P, Davis J (October 2005). "Over-the-counter cold medications-postmortem findings in infants and the relationship to cause of death". J. Anal. Toxicol. 29 (7): 738–43. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.738. PMID 16419411.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Biomedical Publications. pp. 489–492. ISBN 0-9626523-7-7.

- ^ "List of prohibited and controlled drugs according to chapter 96 of the laws of Zambia" (DOC). The Drug Enforcement Commission ZAMBIA.

- ^ "Zambia". Country Information > Zambia. Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Forest E (27 July 2008). "Atypical Drugs of Abuse". Articles & Interviews. Student Doctor Network.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine overdose:". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Further reading

- Charlton BG (2005). "Self-management of psychiatric symptoms using over-the-counter (OTC) psychopharmacology: the S-DTM therapeutic model--Self-diagnosis, self-treatment, self-monitoring". Med. Hypotheses. 65 (5): 823–8. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.07.013. PMID 16111835.

- Lieberman JA (2003). "History of the use of antidepressants in primary care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion J. Clinical Psychiatry. 5 (supplement 7): 6–10.

- Cox D, Ahmed Z, McBride AJ (March 2001). "Diphenhydramine dependence". Addiction. 96 (3): 516–7. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96350713.x. PMID 11310441.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Björnsdóttir I, Einarson TR, Gudmundsson LS, Einarsdóttir RA (December 2007). "Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review". Pharm. World Sci. 29 (6): 577–83. doi:10.1007/s11096-007-9122-2. PMID 17486423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Prescription Information (PDF)

- Diphenhydramine University of Maryland Medical Center Medical References