Cannabidiol

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

Schedule II (Can) (THC - Schedule/Level I; THC and CBD two main chemicals in cannabis) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 13-19% (oral),[1] 11-45% (mean 31%; inhaled)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 9 h[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.215.986 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

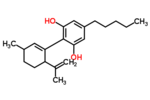

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.4636 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 66 °C (151 °F) |

| Boiling point | 180 °C (356 °F) (range: 160–180 °C)[3] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cannabidiol (CBD) is one of at least 85 cannabinoids found in cannabis.[4] It is a major constituent of the plant, second to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and represents up to 40% in its extracts.[5] Compared with THC, cannabidiol is psychoactive but not intoxicating, and is considered to have a wider scope of medical applications than THC,[6] including to epilepsy,[7] multiple sclerosis spasms,[8] anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder,[6] schizophrenia,[9] nausea, convulsion and inflammation, as well as inhibiting cancer cell growth.[10] There is some preclinical evidence from studies in animals that suggests CBD may modestly reduce the clearance of THC from the body by interfering with its metabolism.[11][12][13] Cannabidiol has displayed sedative effects in animal tests.[14] Other research indicates that CBD increases alertness.[15] CBD has been shown to reduce growth of aggressive human breast cancer cells in vitro, and to reduce their invasiveness.[16]

Clinical applications

Antimicrobial actions

CBD has been shown to inhibit methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in vitro.[17] CBD, along with the cannabis terpenoid pinene, is effective against MRSA, and may exhibit antiseptic effects against Propionibacterium acnes, the key pathogen in acne. CBD absorbed transcutaneously may also attenuate the increased sebum production at the root of acne.[18]

Neurological effects

A 2010 study found that strains of cannabis containing higher concentrations of cannabidiol did not produce short-term memory impairment vs. strains with similar concentrations of THC, but lower concentrations of CBD.[19] The researchers attributed this attenuation of memory effects to CBD's role as a CB1 antagonist.[20] CBD also appears to protect against 'binge' alcohol induced neurodegeneration.[21][22]

There have been numerous case reports and one small clinical trial documenting the ability of CBD to reduce seizure frequency in epilepsy including in treatment-refractory cases of childhood epilepsy syndromes (for example dravet syndrome).[23][24][25]

Cannabidiol's strong antioxidant properties have been shown to play a role in the compound's neuroprotective and anti-ischemic effects.[10]

Cannabidiol has proven effective in treating an often drug-induced set of neurological movement disorders known as dystonia.[26] In one study, five out of five participants showed noted improvement in their dystonic symptoms by 20-50%.[26][27][27]

Parkinson's disease

In 1985, a single case study suggested that CBD may be effective in the management of levodopa-induced dyskinesia in a Parkinson's disease patient.[28] A small open-label clinical trial demonstrated therapeutic benefit of cannabidiol in Parkinson's disease psychosis.[29] This condition is often particularly problematic to treat seeing how Parkinson's disease involves the gradual destruction of the dopaminergic cells of the nigrostriatal pathway and most antipsychotics (with the exception of clozapine and quetiapine) significantly inhibit nigrostriatal dopamine activity (although this is not their intended action as it is the mesolimbic dopamine pathway they are intended to inhibit).[30]

Psychotropic effects

A 2008 study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry showed significant differences in the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences scores among three groups: the first consisted of non-cannabis users, the second consisted of users with THC detected, and the third consisted of users with both THC and CBD detected. The THC-only group scored significantly higher for unusual experiences than the THC-and-CBD group, whereas the THC-and-CBD group had significantly lower introvertive anhedonia scores than the THC-only group and the non-cannabis user group. This research indicates that CBD acts as an anti-psychotic and may counteract the potential psychotomimetic effects of THC on individuals with latent schizophrenia.[31]

Recent studies have shown cannabidiol to be as effective as atypical antipsychotics in treating schizophrenia.[9] Studies have shown CBD may reduce schizophrenic symptoms due to its apparent ability to stabilize disrupted or disabled NMDA receptor pathways in the brain, which are shared and sometimes contested by norepinephrine and GABA.[9][32] Leweke et al. performed a double blind, 4 week, explorative controlled clinical trial to compare the effects of purified cannabidiol and the atypical antipsychotic amisulpride on improving the symptoms of schizophrenia in 42 patients with acute paranoid schizophrenia. Both treatments were associated with a significant decrease of psychotic symptoms after 2 and 4 weeks as assessed by Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. While there was no statistical difference between the two treatment groups, cannabidiol induced significantly fewer side effects (extrapyramidal symptoms, increase in prolactin, weight gain) when compared to amisulpride.[33]

Studies have shown cannabidiol decreases activity of the limbic system[34] and decreases social isolation induced by THC.[35] Cannabidiol has also been shown to reduce anxiety in social anxiety disorder.[36][37] Although in rats chronic cannabidiol administration was recently found to produce anxiogenic-like effects, hence indicating that, prolonged treatment with cannabidiol might incite anxiogenic effects.[38]

Cannabidiol has demonstrated antidepressant-like effects in animal models of depression.[39][40][41]

Cancer research

In November 2007, researchers at the California Pacific Medical Center reported that CBD shows promise for controlling the spread of metastatic breast cancer. In vitro CBD down-regulates, or "turns off", the activity of ID1, the gene responsible for tumor metastasis[16] in breast and other types of cancers, including the particularly aggressive triple negative breast cancer.[16][42][43] The researchers in September 2012 said they hope to start human trials soon.[44]

Cannabidiol has been shown to inhibit cancer cell growth with low potency in non-cancer cells. Although the inhibitory mechanism is not yet fully understood, Ligresti et al. suggest that "cannabidiol exerts its effects on these cells through a combination of mechanisms that include either direct or indirect activation of CB2 and TRPV1 receptors, and induction of oxidative stress, all contributing to induce apoptosis."[43]

Non-intoxicating cannabinoids, including cannabidiol (CBD) and other more pronounced CB2 agonists such as cannabinol (CBN, an immunosuppressant), are now seen as promising targets for anti-tumor drugs since they experimentally reduce the size of in-vivo xenografts, for example gliomas. Combinations of submaximal THC doses and CBD have both been successfully applied to greatly increase in-vitro efficacy of temozolomide in glioblastoma multiforme cell lines. CBD likely exerts its effects through the induction of apoptosis by Reactive oxygen species.[45] Non-psychoactive cannabinoids can be administered at much higher doses without the well-known side effects that are sometimes associated with the drop-out rate in trials involving psychoactive cannabinoids.

A team of researchers from the University of California at Irvine proposed in February 2013 that CBD's anti-malignant effect by way of apoptosis may be due to its potential action on "mutant p53 proteins in cancer cells," due to cannabidiol's chemo-physical similarity to stictic acid, a promising anti-cancer compound found in some species of lichens that acts on the aforementioned proteins. The University biologists, chemists and computer scientists "identified an elusive pocket on the surface of the p53 protein that can be targeted by cancer-fighting drugs".[46][47]

Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome is a rare form of epilepsy that is resistant to most anti-epileptic medications. In the October 2013 edition of The Nation, CBD was touted as the "single compound in cannabis [that] may revolutionize modern medicine". The article went on to say that "nothing else is able to help treatment-resistant epileptic children with Dravet syndrome and related disorders."[48]

The 2013 CNN documentary Weed: Dr. Sanjay Gupta Reports featured a medical marijuana strain called Charlotte's Web, which contains virtually no THC and a high percentage of CBD (0.76% THC and 17.61% CBD) that was being used successfully to treat a 5-year-old Colorado medical marijuana patient who suffers with Dravet syndrome.[49] In 2010, a Modesto, California father reported that he had experienced success treating his son's case of Dravet Syndrome with a CBD-rich cannabis tincture. His 5-year-old son went from a daily dose of 22 pharmaceutical pills down to four, began eating solid food, and experiencing fewer and less intense seizures since beginning treatment with CBD.[50] Before using the tincture, the boy experienced seizures "24 hours a day lasting an hour and a half", but since the first day the high-CBD tincture was administered, he has been seizure-free.[51]

CBD-enhanced cannabis

Decades ago, growers in the US bred CBD almost entirely out of cannabis plants because their customers preferred varietals that were more mind-altering due to a higher THC, lower CBD content.[50] To meet the demands of medical cannabis patients, growers are developing more CBD-rich strains.[52]

In November 2012, an Israeli medical cannabis facility announced a new strain of the plant which has only cannabidiol as an active ingredient, and virtually no THC, providing some of the medicinal benefits of cannabis without the euphoria.[53][54] The researchers said the cannabis plant, enriched with CBD, "can be used for treating diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, liver inflammation, heart disease and diabetes". Research on CBD enhanced cannabis began in 2009, resulting in Avidekel, a cannabis strain that contains 15.8% CBD and less than 1% THC. Raphael Mechoulam, leading cannabinoid researcher, noted "It is possible that (Avidekel's) CBD to THC ratio is the highest among medical marijuana companies in the world, but the industry is not very organized, so one cannot keep exact track of what each company is doing".[55]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Cannabidiol has a very low affinity for CB1 and CB2 receptors but acts as an indirect antagonist of their agonists.[10][56] While one would assume that this would cause cannabidiol to reduce the effects of THC, it may potentiate THC's effects by increasing CB1 receptor density or through another CB1-related mechanism.[57] It is also an inverse agonist of CB2 receptors.[10][56] Recently, it was found to be an antagonist at the putative new cannabinoid receptor, GPR55, a GPCR expressed in the caudate nucleus and putamen.[58] Cannabidiol has also been shown to act as a 5-HT1A receptor agonist,[59] an action which is involved in its antidepressant,[39][60] anxiolytic,[60][61] and neuroprotective[62][63] effects. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator of μ and δ-opioid receptors.[64] Cannabidiol's pharmacologial effects have also been attributed to PPAR-γ receptor agonism and intracellular calcium release.[65]

Pharmacokinetic interactions

There is some preclinical evidence to suggest that cannabidiol may reduce THC clearance, modestly increasing THC's plasma concentrations resulting in a greater amount of THC available to receptors, increasing the effect of THC in a dose-dependent manner.[11][12][13] Despite this the available evidence in humans suggests no significant effect of CBD on THC plasma levels.[66]

Pharmaceutical preparations

A CBD extract made from industrial hemp was introduced to the US market in 2012. Because the FDA considers cannabinoids derived from hemp to be "food-based" products, no legal restrictions exist.[67]

Nabiximols (USAN, trade name Sativex) is an aerosolized mist for oral administration containing a near 1:1 ratio of CBD and THC. The drug was approved by Canadian authorities in 2005 to alleviate pain associated with multiple sclerosis.[68][69][70]

Isomerism

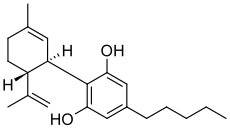

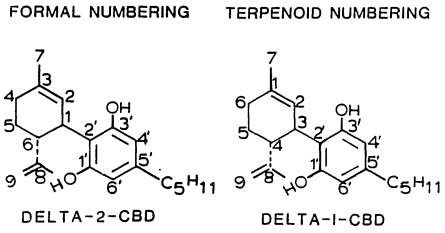

| 7 double bond isomers and their 30 stereoisomers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal numbering | Terpenoid numbering | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | Structure | |||

| Short name | Chiral centers | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers | ||||

| Δ5-cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-5-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ4-cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ4-cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-4-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ5-cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 4 | 8 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ3-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-3-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ6-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | ? | unscheduled |

|

| Δ3,7-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methylenecyclohex-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1,7-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ2-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | unscheduled |

|

| Δ1-cannabidiol | 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ2-cannabidiol | 1 and 4 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ6-cannabidiol | 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-6-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ3-cannabidiol | 1 | 2 | No | unscheduled |

|

See also: Tetrahydrocannabinol#Isomerism, Abnormal cannabidiol.

Chemistry

Cannabidiol is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents, such as pentane. At room temperature it is a colorless crystalline solid.[71] In strongly basic medium and the presence of air it is oxidized to a quinone.[72] Under acidic conditions it cyclizes to THC.[73] The synthesis of cannabidiol has been accomplished by several research groups.[74][75][76]

Biosynthesis

Cannabis produces CBD-carboxylic acid through the same metabolic pathway as THC, until the last step, where CBDA synthase performs catalysis instead of THCA synthase.[77]

Natural occurrence

Cannabis indica may have a CBD:THC ratio 3–5 times that of Cannabis sativa.

Legal status

Cannabidiol is not scheduled by the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Cannabidiol is a Schedule II drug in Canada.[78]

The legal status of cannabidiol in United States is unclear. In Schedule I[79][80] there is a broad category called "Tetrahydrocannabinols", although cannabidiol is not chemically a tetrahydrocannabinol. Cannabidiol has DEA statistical number 7372,[81].

References

- ^ a b Mechoulam, R; Parker, LA; Gallily, R (November 2002). "Cannabidiol: an overview of some pharmacological aspects". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11 Suppl): 11S–19S. doi:10.1177/0091270002238789. PMID 12412831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scuderi, C; Filippis, DD; Iuvone, T; Blasio, A; Steardo, A; Esposito, G (May 2009). "Cannabidiol in Medicine: A Review of its Therapeutic Potential in CNS Disorders". Phytotherapy Research. 23 (5): 597–602. doi:10.1002/ptr.2625. PMID 18844286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McPartland, JM; Russo, EB (2001). "Cannabis and Cannabis Extracts: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts?" (PDF). Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1 (3/4): 103–132. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_08.

- ^ El-Alfy, Abir T; et al. (2010). "Antidepressant-like effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L." Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 95 (4): 434–42. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004. PMC 2866040. PMID 20332000.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grlić, Ljubiša (1962). "A comparative study on some chemical and biological characteristics of various samples of cannabis resin". Bulletin on Narcotics (3). UNODC: 37–46.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Ashton, CH; Moore, PB; Gallagher, P; Young, AH (May 2005). "Cannabinoids in bipolar affective disorder: a review and discussion of their therapeutic potential". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 19 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1177/0269881105051541. PMID 15888515.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22520455, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22520455instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21449980, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21449980instead. - ^ a b c Zuardi, A.W (2006). "Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an antipsychotic drug" (PDF). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 39 (4): 421–429. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2006000400001. PMID 16612464.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Mechoulam, R. (21 Aug 2007). "Cannabidiol - recent advances". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 4 (8): 1678–1692. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bornheim, LM; Kim, KY; Li, J; Perotti, BY; Benet, LZ (August 1995). "Effect of cannabidiol pretreatment on the kinetics of tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in mouse brain". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 23 (8): 825–831. PMID 7493549.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zuardi, AW; Hallak, JE; Crippa, JA (2012). "Interaction between cannabidiol (CBD)

and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): influence of administration interval and dose ratio between the cannabinoids". Psychopharmacology. 219 (1): 247–249. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2495-x. PMID 21947314.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 38 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Klein, C; Karanges, E; Spiro, A; Wong, A; Spencer, J; Huynh, T; Gunasekaran, N; Karl, T; Long, LE; Huang, XF; Liu, K; Arnold, JC; McGregor, IS (November 2011). "Cannabidiol potentiates Δ⁹-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) behavioural effects and alters THC pharmacokinetics during acute and chronic treatment in adolescent rats". Psychopharmacology. 218 (2): 443–457. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2342-0. PMID 21667074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pickens JT (1981). "Sedative activity of cannabis in relation to its delta'-trans-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol content". Br. J. Pharmacol. 72 (4): 649–56. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09145.x. PMC 2071638. PMID 6269680.

- ^ Nicholson, AN (2004). "Effect of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on nocturnal sleep and early-morning behavior in young adults" (PDF). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 24 (3): 305–13. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000125688.05091.8f. ISSN 0271-0749. PMID 15118485.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c McAllister SD, Christian RT, Horowitz MP, Garcia A, Desprez PY (2007). "Cannabidiol as a novel inhibitor of Id-1 gene expression in aggressive breast cancer cells". Mol. Cancer Ther. 6 (11): 2921–7. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0371. PMID 18025276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18681481, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18681481instead. - ^ Russo, E. B (2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (7): 1344–1364. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/news.2010.508, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/news.2010.508instead. - ^ Morgan, C. J.; Schafer, G.; Freeman, T. P.; Curran, H. V. (2010). "Impact of cannabidiol on the acute memory and psychotomimetic effects of smoked cannabis: naturalistic study: naturalistic study [corrected]". British Journal of Psychiatry. 197 (4): 285–90. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077503. PMID 20884951.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1124/jpet.105.085779, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1124/jpet.105.085779instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19631736, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19631736instead. - ^ Gloss, D; Vickrey, B (June 2012). "Cannabinoids for epilepsy (Review)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD009270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub2. PMID 22696383.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Melville, NA (14 August 2013). "Seizure Disorders Enter Medical Marijuana Debate". Medscape Medical News. WebMD. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Cortesi, M; Fusar-Poli, P (2007). "Potential therapeutical effects of cannabidiol in children with pharmacoresistant epilepsy". Medical Hypotheses. 68 (4): 920–921. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.09.030. PMID 17112679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Snider, Stuart R.; Consroe, Paul (1985). "Beneficial and Adverse Effects of Cannabidiol in a Parkinson Patient with Sinemet-Induced Dystonic Dyskinesia". Neurology. 35 (Suppl 1): 201.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3793381, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=3793381instead. - ^ Snider, SR (1985). "Beneficial and adverse effects of cannabidiol in a Parkinson patient with sinemet-induced dystonic dyskinesia". Neurology. 35: 201.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zuardi, AW; Crippa, JA; Hallak, JE; Pinto, JP; Chagas, MH; Rodrigues, GG; Dursun, SM; Tumas, V (November 2009). "Cannabidiol for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (8): 979–983. doi:10.1177/0269881108096519. PMID 18801821.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zahodne, LB; Fernandez, HH (2008). "Pathophysiology and treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease: a review". Drugs & Aging. 25 (8): 665–682. doi:10.2165/00002512-200825080-00004. PMC 3045853. PMID 18665659.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046649, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046649instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300838, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.npp.1300838instead. - ^ Leweke, FM (2012). "Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia". Translational Psychiatry. 2 (3): e94. doi:10.1038/tp.2012.15. PMID 22832859.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ José Alexandre de Souza Crippa, Antonio Waldo Zuardi, Griselda E J Garrido, Lauro Wichert-Ana, Ricardo Guarnieri, Lucas Ferrari, Paulo M Azevedo-Marques, Jaime Eduardo Cecílio Hallak, Philip K McGuire and Geraldo Filho Busatto (2003). "Effects of Cannabidiol (CBD) on Regional Cerebral Blood Flow". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (2): 417–426. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300340. PMID 14583744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daniel Thomas Malone, Dennis Jongejana and David Alan Taylora (2009). "Cannabidiol reverses the reduction in social interaction produced by low dose Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 93 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.010. PMID 19393686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mateus M Bergamaschi, Regina Helena Costa Queiroz, Marcos Hortes Nisihara Chagas, Danielle Chaves Gomes de Oliveira, Bruno Spinosa De Martinis, Flávio Kapczinski, João Quevedo, Rafael Roesler, Nadja Schröder, Antonio E Nardi, Rocio Martín-Santos, Jaime Eduardo Cecílio (2011). "Cannabidiol Reduces the Anxiety Induced by Simulated Public Speaking in Treatment-Naïve Social Phobia Patients". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (6): 1219–1226. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.6. PMC 3079847. PMID 21307846.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, Wichert-Ana L, Duran FL, Martin-Santos R, Simões MV, Bhattacharyya S, Fusar-Poli P, Atakan Z, Santos Filho A, Freitas-Ferrari MC, McGuire PK, Zuardi AW, Busatto GF, Hallak JE. (2011). "Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder: a preliminary report". J Psychopharmacol. 25 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1177/0269881110379283. PMID 20829306.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ElBatsh, MM; Assareh, N; Marsden, CA; Kendall, DA (May 2012). "Anxiogenic-like effects of chronic cannabidiol administration in rats". Psychopharmacology. 221 (2): 239–247. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2566-z. PMID 22083592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zanelati, T; Biojone, C; Moreira, F; Guimarães, F; Joca, S (2010). "Antidepressant-like effects of cannabidiol in mice: possible involvement of 5-HT1A receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 122–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00521.x. PMC 2823358. PMID 20002102.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Réus, GZ; Stringari, RB; Ribeiro, KF; Luft, T; Abelaira, HM; Fries, GR; Aguiar, BW; Kapczinski, F; Hallak, JE; Zuardi, AW; Crippa JA; Quevedo, J (October 2011). "Administration of cannabidiol and imipramine induces antidepressant-like effects in the forced swimming test and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in the rat amygdala". Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 23 (5): 241–248. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00579.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ El-Alfy, AT; Ivey, K; Robinson, K; Ahmed, S; Radwan, M; Slade, D; Khan, I; ElSohly, M; Ross, S (June 2010). "Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L." Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 95 (4): 434–442. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004. PMC 2866040. PMID 20332000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pot compound seen as tool against cancer. SFGate

- ^ a b Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Starowicz K; et al. (2006). "Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318 (3): 1375–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.105247. PMID 16728591.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marijuana Compound Fights Cancer; Human Trials Next. NBC Bay Area

- ^ Velasco; et al. (2011). "A Combined Preclinical Therapy of Cannabinoids and Temozolomide against Glioma". Mol Cancer Ther. 10: 90–103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054795.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ UCI team finds new target for treating wide spectrum of cancers. UCIrvine News

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ncomms2361, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ncomms2361instead. - ^ http://www.thenation.com/article/176910/marijuana-miracle-why-single-compound-cannabis-may-revolutionize-modern-medicine#

- ^ Saundra Young (August 7, 2013). "Marijuana stops child's severe seizures". CNN. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ a b On the frontier of medical pot to treat boy's epilepsy - Los Angeles Times

- ^ Modesto dad turns to medical marijuana to save son | News - KCRA Home

- ^ Video: The rise of high CBD marijuana-Cannabis -Telegraph

- ^ Sidner, Sara (8 November 2012), Medical marijuana without the high (video), CNN,

An Israeli company has cultivated a new type of medical marijuana.

- ^ Solon, Olivia (5 July 2012), "Medical Marijuana Without the High", Wired.com

- ^ Lubell, Maayan (3 July 2012), What a drag, Israeli firm grows "highless" marijuana, Reuters

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.090, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.090instead. - ^ Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S; et al. (2007). "The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (7): 1092–101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460. PMC 2095107. PMID 17876302.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK (2005). "Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors". Neurochemical Research. 30 (8): 1037–43. doi:10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. PMID 16258853.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Resstel LB, Tavares RF, Lisboa SF, Joca SR, Corrêa FM, Guimarães FS (2009). "5-HT1A receptors are involved in the cannabidiol-induced attenuation of behavioural and cardiovascular responses to acute restraint stress in rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (1): 181–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00046.x. PMC 2697769. PMID 19133999.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campos AC, Guimarães FS (2008). "Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats". Psychopharmacology. 199 (2): 223–30. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1168-x. PMID 18446323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mishima K, Hayakawa K, Abe K; et al. (2005). "Cannabidiol prevents cerebral infarction via a serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor-dependent mechanism". Stroke; a Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 36 (5): 1077–82. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000163083.59201.34. PMID 15845890.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M; et al. (2007). "Repeated treatment with cannabidiol but not Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol has a neuroprotective effect without the development of tolerance". Neuropharmacology. 52 (4): 1079–87. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.11.005. PMID 17320118.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16489449, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16489449instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23108553, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23108553instead. - ^ Hunt, CA; Jones, RT; Herning, RI; Bachman, J (June 1981). "Evidence that Cannabidiol Does Not Significantly Alter the Pharmacokinetics of Tetrahydrocannabinol in Man". Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 9 (3): 245–260. doi:10.1007/BF01059266. PMID 6270295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dixie Launches Cannabidiol-Based Dixie Products | Dixie Elixirs & Edibles

- ^ United States Adopted Names Council: Statement on a nonproprietary name

- ^ "Fact Sheet - Sativex". Health Canada. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ GWPharma- Welcome

- ^ Jones PG, Falvello L, Kennard O, Sheldrick GM Mechoulam R (1977). "Cannabidiol". Acta Cryst. B33 (10): 3211–3214. doi:10.1107/S0567740877010577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mechoulam R, Ben-Zvi Z (1968). "Hashish—XIII On the nature of the beam test". Tetrahedron. 24 (16): 5615–5624. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88159-1. PMID 5732891.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1966). "Hashish—VII The isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinols". Tetrahedron. 22 (4): 1481–1488. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99446-3.

- ^ Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C, Ohloff G, Eschenmoser A (1967). "Synthese und Chiralität des (-)-Cannabidiols". Helv. Chim. Acta. 50 (2): 719–723. doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500235. PMID 5587099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1985). "Boron trifluoride etherate on alumuna - a modified Lewis acid reagent. An improved synthesis of cannabidiol". Tetrahedron Letters. 26 (8): 1083–1086. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98518-6.

- ^ Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi A, Wang YG (2006). "Synthesis of cannabidiols via alkenylation of cyclohexenyl monoacetate". Org. Lett. 8 (13): 2699–2702. doi:10.1021/ol060692h. PMID 16774235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/jxb/erp210, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/jxb/erp210instead. - ^ Controlled Drugs and Substances Act - Schedule II

- ^ - Controlled Substance Schedules

- ^ Section 1308.11 Schedule I

- ^ DEA Form 225 - Application for Registration - Manufacturer, Distributor, Researcher, Analytical Laboratory, Importer, Exporter

External links

- Project CBD Non-profit educational service dedicated to promoting and publicizing research into the medical utility of cannabidiol.