Cannabidiol: Difference between revisions

Reverted good faith edits by Tristonlarsen (talk): Revert to WP:MEDRS sources and balanced reading of same. (TW) |

|||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

===Cancer=== |

===Cancer=== |

||

The [[American Cancer Society]] says: "There is no available scientific evidence from controlled studies in humans that cannabinoids can cure or treat cancer."<ref name=Young_Riddle>{{Citation |last=Young |first=Saundra |date=15 Jan 2014 |title=3-year-old is focus of medical marijuana battle |publisher=[[CNN]] |url=http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/15/health/cannabis-landon-riddle/ |accessdate=2014-01-16 }}</ref> Laboratory experiments have been performed on the potential use of cannabinoids for cancer therapy but {{asof|2013|lc=y}} results have been contradictory and knowledge remains |

The [[American Cancer Society]] says: "There is no available scientific evidence from controlled studies in humans that cannabinoids can cure or treat cancer."<ref name=Young_Riddle>{{Citation |last=Young |first=Saundra |date=15 Jan 2014 |title=3-year-old is focus of medical marijuana battle |publisher=[[CNN]] |url=http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/15/health/cannabis-landon-riddle/ |accessdate=2014-01-16 }}</ref> Laboratory experiments have been performed on the potential use of cannabinoids for cancer therapy but {{asof|2013|lc=y}} results have been contradictory and knowledge on cancer-curing cannabinoids remains limited, although there is considerable anecdotal evidence from those who stated they were cured of cancer on YouTube.<ref name=Cridge2013>{{medrs|date=March 2014}}{{cite journal |author=Cridge BJ, Rosengren RJ |title=Critical appraisal of the potential use of cannabinoids in cancer management |journal=Cancer Manag Res |volume=5 |issue= |pages=301–13 |year=2013 |pmid=24039449 |pmc=3770515 |doi=10.2147/CMAR.S36105}}</ref> Cannabinoids have been recommended for cancer pain but the adverse effects may make them a less than ideal treatment; two cannabinoid-based medicines have been approved as a backup remedy for nausea associated with [[chemotherapy]].<ref name=Borgelt2013>{{cite journal |author=Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS |title=The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis |journal=Pharmacotherapy |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=195–209 |date=February 2013 |pmid=23386598 |doi=10.1002/phar.1187 |type=Review}}</ref> |

||

===Dravet syndrome=== |

===Dravet syndrome=== |

||

Revision as of 05:28, 28 June 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Epidiolex |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

Schedule II (Can) (THC - Schedule/Level I; THC and CBD two main chemicals in cannabis) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 13-19% (oral),[1] 11-45% (mean 31%; inhaled)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 9 h[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.215.986 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

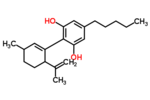

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.4636 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 66 °C (151 °F) |

| Boiling point | 180 °C (356 °F) (range: 160–180 °C)[3] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cannabidiol (CBD) is one of at least 60 active cannabinoids identified in cannabis.[4] It is a major phytocannabinoid, accounting for up to 40% of the plant's extract.[5] CBD is considered to have a wider scope of medical applications than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).[5] An orally-administered liquid containing CBD has received orphan drug status in the US, for use as a treatment for dravet syndrome under the brand name, Epidiolex.[6]

Clinical applications

Antimicrobial actions

CBD absorbed transcutaneously may attenuate the increased sebum production at the root of acne, according to an untested hypothesis.[7]

Neurological effects

A 2010 study found that strains of cannabis containing higher concentrations of cannabidiol did not produce short-term memory impairment vs. strains with similar concentrations of THC, but lower concentrations of CBD. The researchers attributed this attenuation of memory effects to CBD's role as a CB1 antagonist. Transdermal CBD is neuroprotective in animals.[8]

Cannabidiol's strong antioxidant properties have been shown to play a role in the compound's neuroprotective and anti-ischemic effects.[9]

- Parkinson's disease

It has been proposed that CBD may help people with Parkinson's disease, but promising results in animal experiments were not confirmed when CBD was trialled in humans.[10]

Psychotropic effect

CBD has anti-psychotic effects and may counteract the potential psychotomimetic effects of THC on individuals with latent schizophrenia;[5] some reports show it to be an alternative treatment for schizophrenia that is safe and well-tolerated.[11] Studies have shown CBD may reduce schizophrenic symptoms due to its apparent ability to stabilize disrupted or disabled NMDA receptor pathways in the brain, which are shared and sometimes contested by norepinephrine and GABA.[11][12] Leweke et al. performed a double blind, 4 week, explorative controlled clinical trial to compare the effects of purified cannabidiol and the atypical antipsychotic amisulpride on improving the symptoms of schizophrenia in 42 patients with acute paranoid schizophrenia. Both treatments were associated with a significant decrease of psychotic symptoms after 2 and 4 weeks as assessed by Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. While there was no statistical difference between the two treatment groups, cannabidiol induced significantly fewer side effects (extrapyramidal symptoms, increase in prolactin, weight gain) when compared to amisulpride.[13]

Studies have shown cannabidiol decreases activity of the limbic system[14] and decreases social isolation induced by THC.[15] Cannabidiol has also been shown to reduce anxiety in social anxiety disorder.[16][17] However, chronic cannabidiol administration in rats was recently found to produce anxiogenic-like effects, indicating that prolonged treatment with cannabidiol might incite anxiogenic effects.[18]

Cannabidiol has demonstrated antidepressant-like effects in animal models of depression.[19][20][21]

Cancer

The American Cancer Society says: "There is no available scientific evidence from controlled studies in humans that cannabinoids can cure or treat cancer."[22] Laboratory experiments have been performed on the potential use of cannabinoids for cancer therapy but as of 2013[update] results have been contradictory and knowledge on cancer-curing cannabinoids remains limited, although there is considerable anecdotal evidence from those who stated they were cured of cancer on YouTube.[23] Cannabinoids have been recommended for cancer pain but the adverse effects may make them a less than ideal treatment; two cannabinoid-based medicines have been approved as a backup remedy for nausea associated with chemotherapy.[4]

Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome is a rare form of epilepsy that is difficult to treat. Dravet syndrome, also known as Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy of Infancy (SMEI), is a rare and catastrophic form of intractable epilepsy that begins in infancy. Initial seizures are most often prolonged events and in the second year of life other seizure types begin to emerge.[24] While high profile and anecdotal reports have sparked interest in treatment with cannabinoids,[25] there is insufficient medical evidence to draw conclusions about their safety or efficacy.[25][26]

CBD-enhanced cannabis

Decades ago, selective breeding by growers in US dramatically lowered the CBD content of cannabis; their customers preferred varietals that were more mind-altering due to a higher THC, lower CBD content.[27] To meet the demands of medical cannabis patients, growers are currently developing more CBD-rich strains.[28]

In November 2012, Tikun Olam, an Israeli medical cannabis facility announced a new strain of the plant which has only cannabidiol as an active ingredient, and virtually no THC, providing some of the medicinal benefits of cannabis without the euphoria.[29][30] The researchers said the cannabis plant, enriched with CBD, "can be used for treating diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, liver inflammation, heart disease and diabetes". Research on CBD enhanced cannabis began in 2009, resulting in Avidekel, a cannabis strain that contains 15.8% CBD and less than 1% THC. Raphael Mechoulam, a cannabinoid researcher, said "...Avidekel is thought to be the first CBD-enriched cannabis plant with no THC to have been developed in Israel".[31]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Cannabidiol has a very low affinity for CB1 and CB2 receptors but acts as an indirect antagonist of their agonists.[9] While one would assume that this would cause cannabidiol to reduce the effects of THC, it may potentiate THC's effects by increasing CB1 receptor density or through another CB1-related mechanism.[32] It is also an inverse agonist of CB2 receptors.[9][33] Recently, it was found to be an antagonist at the putative new cannabinoid receptor, GPR55, a GPCR expressed in the caudate nucleus and putamen.[34] Cannabidiol has also been shown to act as a 5-HT1A receptor agonist,[35] an action which is involved in its antidepressant,[19][36] anxiolytic,[36][37] and neuroprotective[38][39] effects. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator of μ and δ-opioid receptors.[40] Cannabidiol's pharmacologial effects have also been attributed to PPAR-γ receptor agonism and intracellular calcium release.[5]

Pharmacokinetic interactions

There is some preclinical evidence to suggest that cannabidiol may reduce THC clearance, modestly increasing THC's plasma concentrations resulting in a greater amount of THC available to receptors, increasing the effect of THC in a dose-dependent manner.[41][42] Despite this the available evidence in humans suggests no significant effect of CBD on THC plasma levels.[43]

Pharmaceutical preparations

Nabiximols (USAN, trade name Sativex) is an aerosolized mist for oral administration containing a near 1:1 ratio of CBD and THC. The drug was approved by Canadian authorities in 2005 to alleviate pain associated with multiple sclerosis.[44][45][46]

Isomerism

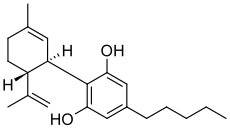

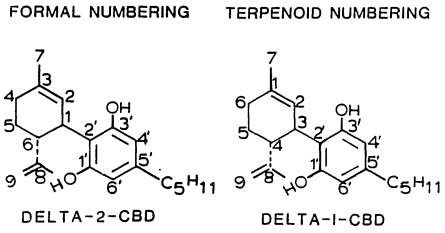

| 7 double bond isomers and their 30 stereoisomers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal numbering | Terpenoid numbering | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | Structure | |||

| Short name | Chiral centers | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers | ||||

| Δ5-cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-5-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ4-cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ4-cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-4-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ5-cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 4 | 8 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ3-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-3-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ6-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | ? | unscheduled |

|

| Δ3,7-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methylenecyclohex-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1,7-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ2-cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1-cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | unscheduled |

|

| Δ1-cannabidiol | 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ2-cannabidiol | 1 and 4 | 4 | No | unscheduled |

|

| Δ6-cannabidiol | 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-6-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ3-cannabidiol | 1 | 2 | No | unscheduled |

|

See also: Tetrahydrocannabinol#Isomerism, Abnormal cannabidiol.

Chemistry

Cannabidiol is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents, such as pentane. At room temperature it is a colorless crystalline solid.[47] In strongly basic medium and the presence of air it is oxidized to a quinone.[48] Under acidic conditions it cyclizes to THC.[49] The synthesis of cannabidiol has been accomplished by several research groups.[50][51][52]

Biosynthesis

Cannabis produces CBD-carboxylic acid through the same metabolic pathway as THC, until the last step, where CBDA synthase performs catalysis instead of THCA synthase.[53]

Legal status

Cannabidiol is not scheduled by the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Cannabidiol is a Schedule II drug in Canada.[54]

Cannabidiol's legal status in the United States:

The DEA Drug Schedule classifies synthetic THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) as a schedule III substance (eg Marinol); while the natural marijuana plant is listed as Schedule I. Cannabidiol is not named specifically on the list.[55] However the CSA does mention all natural Phytocannabinoids in Schedule 1 Code 7372, which would include CBD.[55]

Marijuana (along with all of its cannabinoids) is defined by 21 U.S.C. §802(16), which is part of the Controlled Substances Act.[56][57][58] There is an exemption for certain Hemp products produced abroad. Under this exception, what are known as industrial hemp-finished products are legally imported into the United States each year. Hemp finished products which meet the specific definitions including hemp oil which may contain cannabidiol are legal in the United States but aren't used for getting high.[59]

Some cannabidiol oil is derived from marijuana and therefore contains higher levels of THC.[60] This type of cannabidiol oil would be considered a Schedule I as a result of the THC present.[60]

US patent

In October 2003, U.S. patent #6630507 entitled "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants" was assigned to "The United States Of America As Represented By The Department Of Health And Human Services." The patent was filed in April 1999 and listed as the inventors: Aidan J. Hampson, Julius Axelrod, and Maurizio Grimaldi, who all held positions at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, MD, which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The patent mentions cannabidiol's ability as an antiepileptic, to lower intraocular pressure in the treatment of glaucoma, lack of toxicity or serious side effects in large acute doses, its neuroprotectant properties, its ability to prevent neurotoxicity mediated by NMDA, AMPA, or kainate receptors; its ability to attenuate glutamate toxicity, its ability to protect against cellular damage, its ability to protect brains from ischemic damage, its anxiolytic effect, and its superior antioxidant activity which can be used in the prophylaxis and treatment of oxidation associated diseases.[61]

"Oxidative associated diseases include, without limitation, free radical associated diseases, such as ischemia, ischemic reperfusion injury, inflammatory diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, myocardial ischemia or infarction, cerebrovascular accidents (such as a thromboembolic or hemorrhagic stroke) that can lead to ischemia or an infarct in the brain, operative ischemia, traumatic hemorrhage (for example a hypovolemic stroke that can lead to CNS hypoxia or anoxia), spinal cord trauma, Down's syndrome, Crohn's disease, autoimmune diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes), cataract formation, uveitis, emphysema, gastric ulcers, oxygen toxicity, neoplasia, undesired cellular apoptosis, radiation sickness, and others. The present invention is believed to be particularly beneficial in the treatment of oxidative associated diseases of the CNS, because of the ability of the cannabinoids to cross the blood brain barrier and exert their antioxidant effects in the brain. In particular embodiments, the pharmaceutical composition of the present invention is used for preventing, arresting, or treating neurological damage in Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and HIV dementia; autoimmune neurodegeneration of the type that can occur in encephalitis, and hypoxic or anoxic neuronal damage that can result from apnea, respiratory arrest or cardiac arrest, and anoxia caused by drowning, brain surgery or trauma (such as concussion or spinal cord shock)."[61]

On November 17, 2011, the Federal Register published that the National Institutes of Health of the United States Department of Health and Human Services was "contemplating the grant of an exclusive patent license to practice the invention embodied in U.S. Patent 6,630,507" to the company KannaLife based in New York, for the development and sale of cannabinoid and cannabidiol based therapeutics for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in humans.[62][63][64]

References

- ^ a b Mechoulam R, Parker LA, Gallily R (November 2002). "Cannabidiol: an overview of some pharmacological aspects". J Clin Pharmacol (Review). 42 (11 Suppl): 11S–19S. doi:10.1177/0091270002238789. PMID 12412831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scuderi C, Filippis DD, Iuvone T, Blasio A, Steardo A, Esposito G (May 2009). "Cannabidiol in medicine: a review of its therapeutic potential in CNS disorders". Phytother Res (Review). 23 (5): 597–602. doi:10.1002/ptr.2625. PMID 18844286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [unreliable medical source?] McPartland JM, Russo EB (2001). "Cannabis and cannabis extracts: greater than the sum of their parts?" (PDF). Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1 (3/4): 103–132. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_08.

- ^ a b Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (February 2013). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy (Review). 33 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1002/phar.1187. PMID 23386598.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS (December 2012). "Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. (Review). 367 (1607): 3364–78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0389. PMC 3481531. PMID 23108553.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilner, AN (25 March 2014). "Marijuana for Epilepsy: Weighing the Evidence". Medscape Neurology. WebMD. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Russo EB (August 2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". Br. J. Pharmacol. (Review). 163 (7): 1344–64. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC 3165946. PMID 21749363.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 24012796, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=24012796instead. - ^ a b c Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (August 2007). "Cannabidiol--recent advances". Chem. Biodivers. (Review). 4 (8): 1678–92. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iuvone T, Esposito G, De Filippis D, Scuderi C, Steardo L (2009). "Cannabidiol: a promising drug for neurodegenerative disorders?". CNS Neurosci Ther. 15 (1): 65–75. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00065.x. PMID 19228180.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Hallak JE, Moreira FA, Guimarães FS (April 2006). "Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an antipsychotic drug". Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. (Review). 39 (4): 421–9. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2006000400001. PMID 16612464.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300838, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.npp.1300838instead. - ^ Leweke, FM (2012). "Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia". Translational Psychiatry. 2 (3): e94–. doi:10.1038/tp.2012.15. PMC 3316151. PMID 22832859.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ José Alexandre de Souza Crippa, Antonio Waldo Zuardi, Griselda E J Garrido, Lauro Wichert-Ana, Ricardo Guarnieri, Lucas Ferrari, Paulo M Azevedo-Marques, Jaime Eduardo Cecílio Hallak, Philip K McGuire and Geraldo Filho Busatto (October 2003). "Effects of Cannabidiol (CBD) on Regional Cerebral Blood Flow". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (2): 417–426. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300340. PMID 14583744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daniel Thomas Malone, Dennis Jongejana and David Alan Taylora (August 2009). "Cannabidiol reverses the reduction in social interaction produced by low dose Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 93 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.010. PMID 19393686.

- ^ Mateus M Bergamaschi, Regina Helena Costa Queiroz, Marcos Hortes Nisihara Chagas, Danielle Chaves Gomes de Oliveira, Bruno Spinosa De Martinis, Flávio Kapczinski, João Quevedo, Rafael Roesler, Nadja Schröder, Antonio E Nardi, Rocio Martín-Santos, Jaime Eduardo Cecílio (May 2011). "Cannabidiol Reduces the Anxiety Induced by Simulated Public Speaking in Treatment-Naïve Social Phobia Patients". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (6): 1219–1226. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.6. PMC 3079847. PMID 21307846.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, Wichert-Ana L, Duran FL, Martin-Santos R, Simões MV, Bhattacharyya S, Fusar-Poli P, Atakan Z, Santos Filho A, Freitas-Ferrari MC, McGuire PK, Zuardi AW, Busatto GF, Hallak JE. (January 2011). "Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder: a preliminary report". J Psychopharmacol. 25 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1177/0269881110379283. PMID 20829306.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ElBatsh, MM; Assareh, N; Marsden, CA; Kendall, DA (May 2012). "Anxiogenic-like effects of chronic cannabidiol administration in rats". Psychopharmacology. 221 (2): 239–247. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2566-z. PMID 22083592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zanelati, T; Biojone, C; Moreira, F; Guimarães, F; Joca, S (January 2010). "Antidepressant-like effects of cannabidiol in mice: possible involvement of 5-HT1A receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 122–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00521.x. PMC 2823358. PMID 20002102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Réus, GZ; Stringari, RB; Ribeiro, KF; Luft, T; Abelaira, HM; Fries, GR; Aguiar, BW; Kapczinski, F; Hallak, JE; Zuardi, AW; Crippa JA; Quevedo, J (October 2011). "Administration of cannabidiol and imipramine induces antidepressant-like effects in the forced swimming test and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in the rat amygdala". Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 23 (5): 241–248. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00579.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ El-Alfy, AT; Ivey, K; Robinson, K; Ahmed, S; Radwan, M; Slade, D; Khan, I; ElSohly, M; Ross, S (June 2010). "Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 95 (4): 434–442. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004. PMC 2866040. PMID 20332000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Young, Saundra (15 Jan 2014), 3-year-old is focus of medical marijuana battle, CNN, retrieved 2014-01-16

- ^ [unreliable medical source?]Cridge BJ, Rosengren RJ (2013). "Critical appraisal of the potential use of cannabinoids in cancer management". Cancer Manag Res. 5: 301–13. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S36105. PMC 3770515. PMID 24039449.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ http://www.dravetfoundation.org/dravet-syndrome/what-is-dravet-syndrome#sthash.jAC0bZ89.dpuf What is Dravet Syndrome?

- ^ a b Melville, Nancy A. (14 Aug 2013), Seizure Disorders Enter Medical Marijuana Debate, Medscape Medical News, retrieved 2014-01-14

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gloss D, Vickrey B (13 June 2012). "Cannabinoids for epilepsy". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review). 6: CD009270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub2. PMID 22696383.

- ^ Romney, Lee (13 September 2012). "On the frontier of medical pot to treat boy's epilepsy". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Good, Alastair (26 October 2010). "Growing marijuana that won't get you high". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Sidner, Sara (8 November 2012). "Medical marijuana without the high" (video). CNN.

An Israeli company has cultivated a new type of medical marijuana.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Solon, Olivia (5 July 2012). "Medical Marijuana Without the High". Wired.comTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Lubell, Maayan (3 July 2012). "What a drag, Israeli firm grows 'highless' marijuana". Reuters. Retrieved 31 Jan 2014.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.090, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.090instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442instead. - ^ Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S; et al. (2007). "The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (7): 1092–101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460. PMC 2095107. PMID 17876302.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK (August 2005). "Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors". Neurochemical Research. 30 (8): 1037–43. doi:10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. PMID 16258853.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Resstel LB, Tavares RF, Lisboa SF, Joca SR, Corrêa FM, Guimarães FS (January 2009). "5-HT1A receptors are involved in the cannabidiol-induced attenuation of behavioural and cardiovascular responses to acute restraint stress in rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (1): 181–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00046.x. PMC 2697769. PMID 19133999.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campos AC, Guimarães FS (August 2008). "Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats". Psychopharmacology. 199 (2): 223–30. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1168-x. PMID 18446323.

- ^ Mishima K, Hayakawa K, Abe K; et al. (May 2005). "Cannabidiol prevents cerebral infarction via a serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor-dependent mechanism". Stroke; a Journal of Cerebral Circulation. 36 (5): 1077–82. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000163083.59201.34. PMID 15845890.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M; et al. (March 2007). "Repeated treatment with cannabidiol but not Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol has a neuroprotective effect without the development of tolerance". Neuropharmacology. 52 (4): 1079–87. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.11.005. PMID 17320118.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16489449, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16489449instead. - ^ Bornheim, LM; Kim, KY; Li, J; Perotti, BY; Benet, LZ (August 1995). "Effect of cannabidiol pretreatment on the kinetics of tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in mouse brain". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 23 (8): 825–831. PMID 7493549.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klein, C; Karanges, E; Spiro, A; Wong, A; Spencer, J; Huynh, T; Gunasekaran, N; Karl, T; Long, LE; Huang, XF; Liu, K; Arnold, JC; McGregor, IS (November 2011). "Cannabidiol potentiates Δ⁹-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) behavioural effects and alters THC pharmacokinetics during acute and chronic treatment in adolescent rats". Psychopharmacology. 218 (2): 443–457. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2342-0. PMID 21667074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hunt, CA; Jones, RT; Herning, RI; Bachman, J (June 1981). "Evidence that Cannabidiol Does Not Significantly Alter the Pharmacokinetics of Tetrahydrocannabinol in Man". Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 9 (3): 245–260. doi:10.1007/BF01059266. PMID 6270295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States Adopted Names Council: Statement on a nonproprietary name

- ^ "Fact Sheet - Sativex". Health Canada. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ GWPharma- Welcome

- ^ Jones PG, Falvello L, Kennard O, Sheldrick GM Mechoulam R (1977). "Cannabidiol". Acta Cryst. B33 (10): 3211–3214. doi:10.1107/S0567740877010577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mechoulam R, Ben-Zvi Z (1968). "Hashish—XIII On the nature of the beam test". Tetrahedron. 24 (16): 5615–5624. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88159-1. PMID 5732891.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1966). "Hashish—VII The isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinols". Tetrahedron. 22 (4): 1481–1488. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99446-3.

- ^ Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C, Ohloff G, Eschenmoser A (1967). "Synthese und Chiralität des (-)-Cannabidiols". Helv. Chim. Acta. 50 (2): 719–723. doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500235. PMID 5587099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1985). "Boron trifluoride etherate on alumuna - a modified Lewis acid reagent. An improved synthesis of cannabidiol". Tetrahedron Letters. 26 (8): 1083–1086. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98518-6.

- ^ Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi A, Wang YG (2006). "Synthesis of cannabidiols via alkenylation of cyclohexenyl monoacetate". Org. Lett. 8 (13): 2699–2702. doi:10.1021/ol060692h. PMID 16774235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/jxb/erp210, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/jxb/erp210instead. - ^ Controlled Drugs and Substances Act - Schedule II

- ^ a b CSA Schedule, List of drugs by schedule.

- ^ Definition of marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act.

- ^ Title 21 US Code Controlled Substances Act, text of the CSA.

- ^ Hemp Industries Assn., v. Drug Enforcement Admin., 9th Circuit Court of Appeals case involving industrial hemp.

- ^ Hemp, Many definitions of common terms associated with hemp, including the history of hemp use.

- ^ a b Cannabidiol: The side of marijuana you don't know

- ^ a b US patent 6630507, Hampson, Aidan J.; Axelrod, Julius; Grimaldi, Maurizio, "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants", issued 2003-10-07

- ^ "Federal Register | Prospective Grant of Exclusive License: Development of Cannabinoid(s) and Cannabidiol(s) Based Therapeutics To Treat Hepatic Encephalopathy in Humans". Federalregister.gov. November 17, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "KannaLife Sciences, Inc. Signs Exclusive License Agreement With National Institutes Of Health Office Of Technology Transfer (NIH-OTT)". thestreet.com. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ^ "KannaLife in R&D Collaboration for Cannabinoid-Based Drugs". Genengnews.com. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

External links

- Project CBD Non-profit educational service dedicated to promoting and publicizing research into the medical utility of cannabidiol.