China

People's Republic of China | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "March of the Volunteers" | |

Location of the People's Republic of China | |

| Capital | Beijing 39°55′N 116°23′E / 39.917°N 116.383°E |

| Largest city by municipal boundary | Chongqing[a] |

| Largest city by urban population | Shanghai |

| Official languages | Standard Chinese (de facto)[2] |

| Simplified characters | |

| Ethnic groups (2020)[3] |

|

| Religion (2023)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Chinese |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic |

| Xi Jinping | |

• Premier | Li Qiang |

| Zhao Leji | |

| Wang Huning | |

| Han Zheng | |

| Legislature | National People's Congress[d] |

| Formation | |

| c. 2070 BCE | |

| 221 BCE | |

| 1 January 1912 | |

| 1 October 1949 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 9,596,961 km2 (3,705,407 sq mi)[e][8] (3rd / 4th) |

• Water (%) | 2.8[5] |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• Density | 145[10]/km2 (375.5/sq mi) (83rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium inequality |

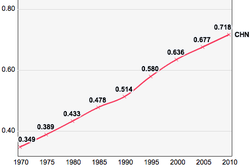

| HDI (2022) | high (75th) |

| Currency | Renminbi (元/¥)[g] (CNY) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| Calling code | |

| ISO 3166 code | CN |

| Internet TLD | |

China,[h] officially the People's Republic of China (PRC),[i] is a country in East Asia. With a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the second-most populous country after India, representing 17.4% of the world population. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and borders fourteen countries by land.[j] With an area of nearly 9.6 million square kilometers (3,700,000 sq mi), it is the third-largest country by total land area.[k] The country is divided into 33 province-level divisions: 22 provinces,[l] five autonomous regions, four municipalities, and two semi-autonomous special administrative regions. Beijing is the country's capital, while Shanghai is its most populous city by urban area and largest financial center.

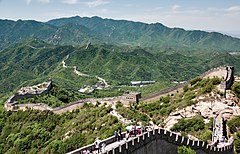

China is considered one of the cradles of civilization: the first human inhabitants in the region arrived during the Paleolithic. By the late 2nd millennium BCE, the earliest dynastic states had emerged in the Yellow River basin. The 8th–3rd centuries BCE saw a breakdown in the authority of the Zhou dynasty, accompanied by the emergence of administrative and military techniques, literature, philosophy, and historiography. In 221 BCE, China was unified under an emperor, ushering in more than two millennia of imperial dynasties including the Qin, Han, Tang, Yuan, Ming, and Qing. With the invention of gunpowder and paper, the establishment of the Silk Road, and the building of the Great Wall, Chinese culture flourished and has heavily influenced both its neighbors and lands further afield. However, China began to cede parts of the country in the late 19th century to various European powers by a series of unequal treaties.

After decades of Qing China on the decline, the 1911 Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty and the monarchy and the nominally democratic Republic of China (ROC) was established the following year. The country under the nascent Beiyang government was unstable and ultimately fragmented during the Warlord Era, which was ended upon the Northern Expedition conducted by the Kuomintang (KMT) to reunify the country. The Chinese Civil War began in 1927, when KMT forces purged members of the rival Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who proceeded to engage in sporadic fighting against the KMT-led Nationalist government. Following the country's invasion by the Empire of Japan in 1937, the CCP and KMT nominally joined forces to fight the Japanese and the Second Sino-Japanese War eventually ended in a Chinese victory; however, the CCP and the KMT resumed their civil war as soon as the war ended. In 1949, the resurgent Communists established control over most of the country, proclaiming the People's Republic of China and forcing the Nationalist government to retreat to the island of Taiwan. The country was split, with both sides claiming to be the sole legitimate government of China. Following the implementation of land reforms, further attempts by the PRC to realize communism failed: the Great Leap Forward was largely responsible for the Great Chinese Famine that ended with millions of Chinese people having died, and the subsequent Cultural Revolution was a period of social turmoil and persecution characterized by Maoist populism. Following the Sino-Soviet split, the Shanghai Communiqué in 1972 would precipitate the normalization of relations with the United States. Economic reforms that began in 1978 moved the country away from a socialist planned economy towards an increasingly capitalist market economy, spurring significant economic growth. The corresponding movement for increased democracy and liberalization stalled after the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in 1989.

China is a unitary one-party socialist republic led by the CCP. It is one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council; the UN representative for China was changed from the ROC to the PRC in 1971. It is a founding member of several multilateral and regional organizations such as the AIIB, the Silk Road Fund, the New Development Bank, and the RCEP. It is a member of the BRICS, the G20, APEC, the SCO, and the East Asia Summit. Making up around one-fifth of the world economy, the Chinese economy is the world's largest economy by PPP-adjusted GDP, the second-largest economy by nominal GDP, and the second-wealthiest country, albeit ranking poorly in measures of democracy, human rights and religious freedom. The country has been one of the fastest-growing major economies and is the world's largest manufacturer and exporter, as well as the second-largest importer. China is a nuclear-weapon state with the world's largest standing army by military personnel and the second-largest defense budget. It is a great power, and has been described as an emerging superpower. China is known for its cuisine and culture, and has 59 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the second-highest number of any country.

Etymology

The word "China" has been used in English since the 16th century; however, it was not used by the Chinese themselves during this period. Its origin has been traced through Portuguese, Malay, and Persian back to the Sanskrit word Cīna, used in ancient India.[16] "China" appears in Richard Eden's 1555 translation[m] of the 1516 journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa.[n][16] Barbosa's usage was derived from Persian Chīn (چین), which in turn derived from Sanskrit Cīna (चीन).[21] Cīna was first used in early Hindu scripture, including the Mahabharata (5th century BCE) and the Laws of Manu (2nd century BCE).[22] In 1655, Martino Martini suggested that the word China is derived ultimately from the name of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).[23][22] Although use in Indian sources precedes this dynasty, this derivation is still given in various sources.[24] The origin of the Sanskrit word is a matter of debate.[16] Alternative suggestions include the names for Yelang and the Jing or Chu state.[22][25]

The official name of the modern state is the "People's Republic of China" (simplified Chinese: 中华人民共和国; traditional Chinese: 中華人民共和國; pinyin: Zhōnghuá rénmín gònghéguó). The shorter form is "China" (中国; 中國; Zhōngguó), from zhōng ('central') and guó ('state'), a term which developed under the Western Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne.[o][p] It was used in official documents as an synonym for the state under the Qing.[28] The name Zhongguo is also translated as 'Middle Kingdom' in English.[29] China is sometimes referred to as "mainland China" or "the Mainland" when distinguishing it from the Republic of China or the PRC's Special Administrative Regions.[30][31][32][33]

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence suggests that early hominids inhabited China 2.25 million years ago.[34] The hominid fossils of Peking Man, a Homo erectus who used fire,[35] have been dated to between 680,000 and 780,000 years ago.[36] The fossilized teeth of Homo sapiens (dated to 125,000–80,000 years ago) have been discovered in Fuyan Cave.[37] Chinese proto-writing existed in Jiahu around 6600 BCE,[38] at Damaidi around 6000 BCE,[39] Dadiwan from 5800 to 5400 BCE, and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that the Jiahu symbols (7th millennium BCE) constituted the earliest Chinese writing system.[38]

Early dynastic rule

According to traditional Chinese historiography, the Xia dynasty was established during the late 3rd millennium BCE, marking the beginning of the dynastic cycle that was understood to underpin China's entire political history. In the modern era, the Xia's historicity came under increasing scrutiny, in part due to the earliest known attestation of the Xia being written millennia after the date given for their collapse. In 1958, archaeologists discovered sites belonging to the Erlitou culture that existed during the early Bronze Age; they have since been characterized as the remains of the historical Xia, but this conception is often rejected.[40][41][42] The Shang dynasty that traditionally succeeded the Xia is the earliest for which there are both contemporary written records and undisputed archaeological evidence.[43] The Shang ruled much of the Yellow River valley until the 11th century BCE, with the earliest hard evidence dated c. 1300 BCE.[44] The oracle bone script, attested from c. 1250 BCE but generally assumed to be considerably older,[45][46] represents the oldest known form of written Chinese,[47] and is the direct ancestor of modern Chinese characters.[48]

The Shang were overthrown by the Zhou, who ruled between the 11th and 5th centuries BCE, though the centralized authority of Son of Heaven was slowly eroded by fengjian lords. Some principalities eventually emerged from the weakened Zhou and continually waged war with each other during the 300-year Spring and Autumn period. By the time of the Warring States period of the 5th–3rd centuries BCE, there were seven major powerful states left.[49]

Imperial China

Qin and Han

The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE after the state of Qin conquered the other six states, reunited China and established the dominant order of autocracy. King Zheng of Qin proclaimed himself the Emperor of the Qin dynasty, becoming the first emperor of a unified China. He enacted Qin's legalist reforms, notably the standardization of Chinese characters, measurements, road widths, and currency. His dynasty also conquered the Yue tribes in Guangxi, Guangdong, and Northern Vietnam.[50] The Qin dynasty lasted only fifteen years, falling soon after the First Emperor's death.[51][52]

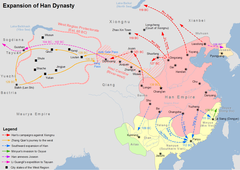

Following widespread revolts during which the imperial library was burned,[q] the Han dynasty emerged to rule China between 206 BCE and 220 CE, creating a cultural identity among its populace still remembered in the ethnonym of the modern Han Chinese.[51][52] The Han expanded the empire's territory considerably, with military campaigns reaching Central Asia, Mongolia, Korea, and Yunnan, and the recovery of Guangdong and northern Vietnam from Nanyue. Han involvement in Central Asia and Sogdia helped establish the land route of the Silk Road, replacing the earlier path over the Himalayas to India. Han China gradually became the largest economy of the ancient world.[54] Despite the Han's initial decentralization and the official abandonment of the Qin philosophy of Legalism in favor of Confucianism, Qin's legalist institutions and policies continued to be employed by the Han government and its successors.[55]

Three Kingdoms, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties

After the end of the Han dynasty, a period of strife known as Three Kingdoms followed, at the end of which Wei was swiftly overthrown by the Jin dynasty. The Jin fell to civil war upon the ascension of a developmentally disabled emperor; the Five Barbarians then rebelled and ruled northern China as the Sixteen States. The Xianbei unified them as the Northern Wei, whose Emperor Xiaowen reversed his predecessors' apartheid policies and enforced a drastic sinification on his subjects. In the south, the general Liu Yu secured the abdication of the Jin in favor of the Liu Song. The various successors of these states became known as the Northern and Southern dynasties, with the two areas finally reunited by the Sui in 581.[citation needed]

Sui, Tang and Song

The Sui restored the Han to power through China, reformed its agriculture, economy and imperial examination system, constructed the Grand Canal, and patronized Buddhism. However, they fell quickly when their conscription for public works and a failed war in northern Korea provoked widespread unrest.[56][57] Under the succeeding Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese economy, technology, and culture entered a golden age.[58] The Tang dynasty retained control of the Western Regions and the Silk Road,[59] which brought traders to as far as Mesopotamia and the Horn of Africa,[60] and made the capital Chang'an a cosmopolitan urban center. However, it was devastated and weakened by the An Lushan rebellion in the 8th century.[61] In 907, the Tang disintegrated completely when the local military governors became ungovernable. The Song dynasty ended the separatist situation in 960, leading to a balance of power between the Song and the Liao dynasty. The Song was the first government in world history to issue paper money and the first Chinese polity to establish a permanent navy which was supported by the developed shipbuilding industry along with the sea trade.[62]

Between the 10th and 11th century CE, the population of China doubled to around 100 million people, mostly because of the expansion of rice cultivation in central and southern China, and the production of abundant food surpluses. The Song dynasty also saw a revival of Confucianism, in response to the growth of Buddhism during the Tang,[63] and a flourishing of philosophy and the arts, as landscape art and porcelain were brought to new levels of complexity.[64] However, the military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jin dynasty. In 1127, Emperor Huizong of Song and the capital Bianjing were captured during the Jin–Song wars. The remnants of the Song retreated to southern China.[65]

Yuan

The Mongol conquest of China began in 1205 with the campaigns against Western Xia by Genghis Khan,[66] who also invaded Jin territories.[67] In 1271, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty, which conquered the last remnant of the Song dynasty in 1279. Before the Mongol invasion, the population of Song China was 120 million citizens; this was reduced to 60 million by the time of the census in 1300.[68] A peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang overthrew the Yuan in 1368 and founded the Ming dynasty as the Hongwu Emperor. Under the Ming dynasty, China enjoyed another golden age, developing one of the strongest navies in the world and a rich and prosperous economy amid a flourishing of art and culture. It was during this period that admiral Zheng He led the Ming treasure voyages throughout the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as East Africa.[69]

Ming

In the early Ming dynasty, China's capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing. With the budding of capitalism, philosophers such as Wang Yangming critiqued and expanded Neo-Confucianism with concepts of individualism and equality of four occupations.[70] The scholar-official stratum became a supporting force of industry and commerce in the tax boycott movements, which, together with the famines and defense against Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) and Later Jin incursions led to an exhausted treasury.[71] In 1644, Beijing was captured by a coalition of peasant rebel forces led by Li Zicheng. The Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide when the city fell. The Manchu Qing dynasty, then allied with Ming dynasty general Wu Sangui, overthrew Li's short-lived Shun dynasty and subsequently seized control of Beijing, which became the new capital of the Qing dynasty.[72]

Qing

The Qing dynasty, which lasted from 1644 until 1912, was the last imperial dynasty of China. The Ming-Qing transition (1618–1683) cost 25 million lives, but the Qing appeared to have restored China's imperial power and inaugurated another flowering of the arts.[73] After the Southern Ming ended, the further conquest of the Dzungar Khanate added Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang to the empire.[74] Meanwhile, China's population growth resumed and shortly began to accelerate. It is commonly agreed that pre-modern China's population experienced two growth spurts, one during the Northern Song period (960–1127), and other during the Qing period (around 1700–1830).[75] By the High Qing era China was possibly the most commercialized country in the world, and imperial China experienced a second commercial revolution by the end of the 18th century.[76] On the other hand, the centralized autocracy was strengthened in part to suppress anti-Qing sentiment with the policy of valuing agriculture and restraining commerce, like the Haijin during the early Qing period and ideological control as represented by the literary inquisition, causing some social and technological stagnation.[77][78]

Fall of the Qing dynasty

In the mid-19th century, the Opium Wars with Britain and France forced China to pay compensation, open treaty ports, allow extraterritoriality for foreign nationals, and cede Hong Kong to the British[79] under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, the first of what have been termed as the "unequal treaties". The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) resulted in Qing China's loss of influence in the Korean Peninsula, as well as the cession of Taiwan to Japan.[80] The Qing dynasty also began experiencing internal unrest in which tens of millions of people died, especially in the White Lotus Rebellion, the failed Taiping Rebellion that ravaged southern China in the 1850s and 1860s and the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) in the northwest. The initial success of the Self-Strengthening Movement of the 1860s was frustrated by a series of military defeats in the 1880s and 1890s.[81]

In the 19th century, the great Chinese diaspora began. Losses due to emigration were added to by conflicts and catastrophes such as the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–1879, in which between 9 and 13 million people died.[82] The Guangxu Emperor drafted a reform plan in 1898 to establish a modern constitutional monarchy, but these plans were thwarted by the Empress Dowager Cixi. The ill-fated anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901 further weakened the dynasty. Although Cixi sponsored a program of reforms known as the late Qing reforms, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912 ended the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China.[83] Puyi, the last Emperor, abdicated in 1912.[84]

Establishment of the Republic and World War II

On 1 January 1912, the Republic of China was established, and Sun Yat-sen of the Kuomintang (KMT) was proclaimed provisional president.[85] In March 1912, the presidency was given to Yuan Shikai, a former Qing general who in 1915 proclaimed himself Emperor of China. In the face of popular condemnation and opposition from his own Beiyang Army, he was forced to abdicate and re-establish the republic in 1916.[86] After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, China was politically fragmented. Its Beijing-based government was internationally recognized but virtually powerless; regional warlords controlled most of its territory.[87][88] During this period, China participated in World War I and saw a far-reaching popular uprising (the May Fourth Movement).[89]

In the late 1920s, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek was able to reunify the country under its own control with a series of deft military and political maneuverings known collectively as the Northern Expedition.[90][91] The Kuomintang moved the nation's capital to Nanjing and implemented "political tutelage", an intermediate stage of political development outlined in Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People program for transforming China into a modern democratic state.[92][93] The Kuomintang briefly allied with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during the Northern Expedition, though the alliance broke down in 1927 after Chiang violently suppressed the CCP and other leftists in Shanghai, marking the beginning of the Chinese Civil War.[94] The CCP declared areas of the country as the Chinese Soviet Republic (Jiangxi Soviet) in November 1931 in Ruijin, Jiangxi. The Jiangxi Soviet was wiped out by the KMT armies in 1934, leading the CCP to initiate the Long March and relocate to Yan'an in Shaanxi. It would be the base of the communists before major combat in the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949.

In 1931, Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria. Japan invaded other parts of China in 1937, precipitating the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), a theater of World War II. The war forced an uneasy alliance between the Kuomintang and the CCP. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population; as many as 20 million Chinese civilians died.[95] An estimated 40,000 to 300,000 Chinese were massacred in Nanjing alone during the Japanese occupation.[96] China, along with the UK, the United States, and the Soviet Union, were recognized as the Allied "Big Four" in the Declaration by United Nations.[97][98] Along with the other three great powers, China was one of the four major Allies of World War II, and was later considered one of the primary victors in the war.[99][100] After the surrender of Japan in 1945, Taiwan, including the Penghu, was handed over to Chinese control; however, the validity of this handover is controversial.[101]

People's Republic

China emerged victorious but war-ravaged and financially drained. The continued distrust between the Kuomintang and the Communists led to the resumption of civil war. Constitutional rule was established in 1947, but because of the ongoing unrest, many provisions of the ROC constitution were never implemented in mainland China.[101] Afterwards, the CCP took control of most of mainland China, and the ROC government retreated offshore to Taiwan.

On 1 October 1949, CCP Chairman Mao Zedong formally proclaimed the People's Republic of China in Tiananmen Square, Beijing.[103] In 1950, the PRC captured Hainan from the ROC[104] and annexed Tibet.[105] However, remaining Kuomintang forces continued to wage an insurgency in western China throughout the 1950s.[106] The CCP consolidated its popularity among the peasants through the Land Reform Movement, which included the state-tolerated executions of between 1 and 2 million landlords by peasants and former tenants.[107] Though the PRC initially allied closely with the Soviet Union, the relations between the two communist nations gradually deteriorated, leading China to develop an independent industrial system and its own nuclear weapons.[108]

The Chinese population increased from 550 million in 1950 to 900 million in 1974.[109] However, the Great Leap Forward, an idealistic massive industrialization project, resulted in an estimated 15 to 55 million deaths between 1959 and 1961, mostly from starvation.[110][111] In 1964, China detonated its first atomic bomb.[112] In 1966, Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, sparking a decade of political recrimination and social upheaval that lasted until Mao's death in 1976. In October 1971, the PRC replaced the ROC in the United Nations, and took its seat as a permanent member of the Security Council.[113]

Reforms and contemporary history

After Mao's death, the Gang of Four was arrested by Hua Guofeng and held responsible for the Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution was rebuked, with millions rehabilitated. Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, and instituted large-scale political and economic reforms, together with the "Eight Elders", most senior and influential members of the party. The government loosened its control and the communes were gradually disbanded.[114] Agricultural collectivization was dismantled and farmlands privatized. While foreign trade became a major focus, special economic zones (SEZs) were created. Inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were restructured and some closed. This marked China's transition away from planned economy.[115] China adopted its current constitution on 4 December 1982.[116]

In 1989, there were protests such those in Tiananmen Square, and then throughout the entire nation.[117] Zhao Ziyang was put under house arrest for his sympathies to the protests and was replaced by Jiang Zemin. Jiang continued economic reforms, closing many SOEs and trimming down "iron rice bowl" (life-tenure positions).[118][119][120] China's economy grew sevenfold during this time.[118] British Hong Kong and Portuguese Macau returned to China in 1997 and 1999, respectively, as special administrative regions under the principle of one country, two systems. The country joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.[118]

At the 16th CCP National Congress in 2002, Hu Jintao succeeded Jiang as the general secretary.[118] Under Hu, China maintained its high rate of economic growth, overtaking the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Japan to become the world's second-largest economy.[121] However, the growth also severely impacted the country's resources and environment,[122][123] and caused major social displacement.[124][125] Xi Jinping succeeded Hu as paramount leader at the 18th CCP National Congress in 2012. Shortly after his ascension to power, Xi launched a vast anti-corruption crackdown,[126] that prosecuted more than 2 million officials by 2022.[127] During his tenure, Xi has consolidated power unseen since the initiation of economic and political reforms.[128]

Geography

China's landscape is vast and diverse, ranging from the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts in the arid north to the subtropical forests in the wetter south. The Himalaya, Karakoram, Pamir and Tian Shan mountain ranges separate China from much of South and Central Asia. The Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, the third- and sixth-longest in the world, respectively, run from the Tibetan Plateau to the densely populated eastern seaboard. China's coastline along the Pacific Ocean is 14,500 km (9,000 mi) long and is bounded by the Bohai, Yellow, East China and South China seas. China connects through the Kazakh border to the Eurasian Steppe.

The territory of China lies between latitudes 18° and 54° N, and longitudes 73° and 135° E. The geographical center of China is marked by the Center of the Country Monument at 35°50′40.9″N 103°27′7.5″E / 35.844694°N 103.452083°E. China's landscapes vary significantly across its vast territory. In the east, along the shores of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea, there are extensive and densely populated alluvial plains, while on the edges of the Inner Mongolian plateau in the north, broad grasslands predominate. Southern China is dominated by hills and low mountain ranges, while the central-east hosts the deltas of China's two major rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangtze River. Other major rivers include the Xi, Mekong, Brahmaputra and Amur. To the west sit major mountain ranges, most notably the Himalayas. High plateaus feature among the more arid landscapes of the north, such as the Taklamakan and the Gobi Desert. The world's highest point, Mount Everest (8,848 m), lies on the Sino-Nepalese border.[129] The country's lowest point, and the world's third-lowest, is the dried lake bed of Ayding Lake (−154 m) in the Turpan Depression.[130]

Climate

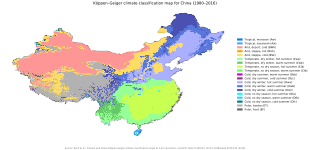

China's climate is mainly dominated by dry seasons and wet monsoons, which lead to pronounced temperature differences between winter and summer. In the winter, northern winds coming from high-latitude areas are cold and dry; in summer, southern winds from coastal areas at lower latitudes are warm and moist.[132]

A major environmental issue in China is the continued expansion of its deserts, particularly the Gobi Desert.[133][134] Although barrier tree lines planted since the 1970s have reduced the frequency of sandstorms, prolonged drought and poor agricultural practices have resulted in dust storms plaguing northern China each spring, which then spread to other parts of East Asia, including Japan and Korea. Water quality, erosion, and pollution control have become important issues in China's relations with other countries. Melting glaciers in the Himalayas could potentially lead to water shortages for hundreds of millions of people.[135] According to academics, in order to limit climate change in China to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) electricity generation from coal in China without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[136] With current policies, the GHG emissions of China will probably peak in 2025, and by 2030 they will return to 2022 levels. However, such pathway still leads to three-degree temperature rise.[137]

Official government statistics about Chinese agricultural productivity are considered unreliable, due to exaggeration of production at subsidiary government levels.[138][139] Much of China has a climate very suitable for agriculture and the country has been the world's largest producer of rice, wheat, tomatoes, eggplant, grapes, watermelon, spinach, and many other crops.[140] In 2021,12 percent of global permanent meadows and pastures belonged to China, as well as 8% of global cropland.[141]

Biodiversity

China is one of 17 megadiverse countries,[142] lying in two of the world's major biogeographic realms: the Palearctic and the Indomalayan. By one measure, China has over 34,687 species of animals and vascular plants, making it the third-most biodiverse country in the world, after Brazil and Colombia.[143] The country is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity;[144] its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan was received by the convention in 2010.[145]

China is home to at least 551 species of mammals (the third-highest in the world),[146] 1,221 species of birds (eighth),[147] 424 species of reptiles (seventh)[148] and 333 species of amphibians (seventh).[149] Wildlife in China shares habitat with, and bears acute pressure from, one of the world's largest population of humans. At least 840 animal species are threatened, vulnerable or in danger of local extinction, due mainly to human activity such as habitat destruction, pollution and poaching for food, fur and traditional Chinese medicine.[150] Endangered wildlife is protected by law, and as of 2005[update], the country has over 2,349 nature reserves, covering a total area of 149.95 million hectares, 15 percent of China's total land area.[151] Most wild animals have been eliminated from the core agricultural regions of east and central China, but they have fared better in the mountainous south and west.[152][153] The Baiji was confirmed extinct on 12 December 2006.[154]

China has over 32,000 species of vascular plants,[155] and is home to a variety of forest types. Cold coniferous forests predominate in the north of the country, supporting animal species such as moose and Asian black bear, along with over 120 bird species.[156] The understory of moist conifer forests may contain thickets of bamboo. In higher montane stands of juniper and yew, the bamboo is replaced by rhododendrons. Subtropical forests, which are predominate in central and southern China, support a high density of plant species including numerous rare endemics. Tropical and seasonal rainforests, though confined to Yunnan and Hainan, contain a quarter of all the animal and plant species found in China.[156] China has over 10,000 recorded species of fungi.[157]

Environment

In the early 2000s, China has suffered from environmental deterioration and pollution due to its rapid pace of industrialization.[158][159] Regulations such as the 1979 Environmental Protection Law are fairly stringent, though they are poorly enforced, frequently disregarded in favor of rapid economic development.[160] China has the second-highest death toll because of air pollution, after India, with approximately 1 million deaths.[161][162] Although China ranks as the highest CO2 emitting country,[163] it only emits 8 tons of CO2 per capita, significantly lower than developed countries such as the United States (16.1), Australia (16.8) and South Korea (13.6).[164] Greenhouse gas emissions by China are the world's largest.[164] The country has significant water pollution problems; only 89.4% of China's national surface water was graded suitable for human consumption by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2023.[165]

China has prioritized clamping down on pollution, bringing a significant decrease in air pollution in the 2010s.[166] In 2020, the Chinese government announced its aims for the country to reach its peak emissions levels before 2030, and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 in line with the Paris Agreement,[167] which, according to Climate Action Tracker, would lower the expected rise in global temperature by 0.2–0.3 degrees – "the biggest single reduction ever estimated by the Climate Action Tracker".[167]

China is the world's leading investor in renewable energy and its commercialization, with $546 billion invested in 2022;[168] it is a major manufacturer of renewable energy technologies and invests heavily in local-scale renewable energy projects.[169][168] Long heavily relying on non-renewable energy sources such as coal, China's adaptation of renewable energy has increased significantly in recent years, with their share increasing from 26.3 percent in 2016 to 31.9 percent in 2022.[170] In 2023, 60.5% of China's electricity came from coal (largest producer in the world), 13.2% from hydroelectric power (largest), 9.4% from wind (largest), 6.2% from solar energy (largest), 4.6% from nuclear energy (second-largest), 3.3% from natural gas (fifth-largest), and 2.2% from bioenergy (largest); in total, 31% of China's energy came from renewable energy sources.[171] Despite its emphasis on renewables, China remains deeply connected to global oil markets and next to India, has been the largest importer of Russian crude oil in 2022.[172][173]

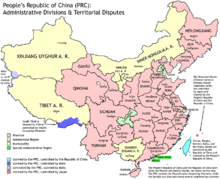

Political geography

China is the third-largest country in the world by land area after Russia, and the third- or fourth-largest country in the world by total area.[r] China's total area is generally stated as being approximately 9,600,000 km2 (3,700,000 sq mi).[174] Specific area figures range from 9,572,900 km2 (3,696,100 sq mi) according to the Encyclopædia Britannica,[14] to 9,596,961 km2 (3,705,407 sq mi) according to the UN Demographic Yearbook,[6] and The World Factbook.[5]

China has the longest combined land border in the world, measuring 22,117 km (13,743 mi) and its coastline covers approximately 14,500 km (9,000 mi) from the mouth of the Yalu River (Amnok River) to the Gulf of Tonkin.[5] China borders 14 nations and covers the bulk of East Asia, bordering Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar in Southeast Asia; India, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan[s] and Afghanistan in South Asia; Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia; and Russia, Mongolia, and North Korea in Inner Asia and Northeast Asia. It is narrowly separated from Bangladesh and Thailand to the southwest and south, and has several maritime neighbors such as Japan, Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.[175]

China has resolved its land borders with 12 out of 14 neighboring countries, having pursued substantial compromises in most of them.[176][177][178] China currently has a disputed land border with India[179] and Bhutan.[180] China is additionally involved in maritime disputes with multiple countries over territory in the East and South China Seas, such as the Senkaku Islands and the entirety of South China Sea Islands.[181][182]

Government and politics

The People's Republic of China is a one-party state governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP is officially guided by socialism with Chinese characteristics, which is Marxism adapted to Chinese circumstances.[183] The Chinese constitution states that the PRC "is a socialist state governed by a people's democratic dictatorship that is led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants," that the state institutions "shall practice the principle of democratic centralism,"[184] and that "the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party."[185]

The PRC officially terms itself as a democracy, using terms such as "socialist consultative democracy",[186] and "whole-process people's democracy".[187] However, the country is commonly described as an authoritarian one-party state and a dictatorship,[188][189] with among the heaviest restrictions worldwide in many areas, most notably against freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, free formation of social organizations, freedom of religion and free access to the Internet.[190] China has consistently been ranked amongst the lowest as an "authoritarian regime" by the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index, ranking at 148th out of 167 countries in 2023.[191] Other sources suggest that terming China as "authoritarian" does not sufficiently account for the multiple consultation mechanisms that exist in Chinese government.[192]

Chinese Communist Party

According to the CCP constitution, its highest body is the National Congress held every five years.[193] The National Congress elects the Central Committee, who then elects the party's Politburo, Politburo Standing Committee and the general secretary (party leader), the top leadership of the country.[193] The general secretary holds ultimate power and authority over party and state and serves as the informal paramount leader.[194] The current general secretary is Xi Jinping, who took office on 15 November 2012.[195] At the local level, the secretary of the CCP committee of a subdivision outranks the local government level; CCP committee secretary of a provincial division outranks the governor while the CCP committee secretary of a city outranks the mayor.[196]

Government

The government in China is under the sole control of the CCP.[197] The CCP controls appointments in government bodies, with most senior government officials being CCP members.[197]

The National People's Congress (NPC), with nearly 3,000-members, is constitutionally the "highest organ of state power",[184] though it has been also described as a "rubber stamp" body.[198] The NPC meets annually, while the NPC Standing Committee, around 150 members elected from NPC delegates, meets every couple of months.[198] Elections are indirect and not pluralistic, with nominations at all levels being controlled by the CCP.[187] The NPC is dominated by the CCP, with another eight minor parties having nominal representation under the condition of upholding CCP leadership.[199]

The president is elected by the NPC. The presidency is the ceremonial state representative, but not the constitutional head of state. The incumbent president is Xi Jinping, who is also the general secretary of the CCP and the chairman of the Central Military Commission, making him China's paramount leader and supreme commander of the Armed Forces. The premier is the head of government, with Li Qiang being the incumbent. The premier is officially nominated by the president and then elected by the NPC, and has generally been either the second- or third-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). The premier presides over the State Council, China's cabinet, composed of four vice premiers, state councilors, and the heads of ministries and commissions.[184] The Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is a political advisory body that is critical in China's "united front" system, which aims to gather non-CCP voices to support the CCP. Similar to the people's congresses, CPPCC's exist at various division, with the National Committee of the CPPCC being chaired by Wang Huning, fourth-ranking member of the PSC.[200]

The governance of China is characterized by a high degree of political centralization but significant economic decentralization.[201]: 7 Policy instruments or processes are often tested locally before being applied more widely, resulting in a policy that involves experimentation and feedback.[202]: 14 Generally, central government leadership refrains from drafting specific policies, instead using the informal networks and site visits to affirm or suggest changes to the direction of local policy experiments or pilot programs.[203]: 71 The typical approach is that central government leadership begins drafting formal policies, law, or regulations after policy has been developed at local levels.[203]: 71

Administrative divisions

The PRC is constitutionally a unitary state divided into 23 provinces,[t] five autonomous regions (each with a designated minority group), and four direct-administered municipalities—collectively referred to as "mainland China"—as well as the special administrative regions (SARs) of Hong Kong and Macau.[204] The PRC regards the island of Taiwan as its Taiwan Province, Kinmen and Matsu as a part of Fujian Province and islands the ROC controls in the South China Sea as a part of Hainan Province and Guangdong Province, although all these territories are governed by the Republic of China (ROC).[205][33] Geographically, all 31 provincial divisions of mainland China can be grouped into six regions: North China, East China, Southwestern China, Northwestern China, South Central China, and Northeast China.[206]

| Provinces (省) |

|

|---|---|

| Claimed Province |

Taiwan (台湾省), governed by the Republic of China |

| Autonomous regions (自治区) |

|

| Municipalities (直辖市) | |

| Special administrative regions (特别行政区) |

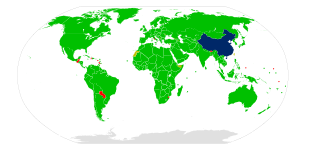

Foreign relations

The PRC has diplomatic relations with 179 United Nation members states and maintains embassies in 174. As of 2024[update], China has one of the largest diplomatic networks of any country in the world.[207] In 1971, the PRC replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as the sole representative of China in the United Nations and as one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.[208] It is a member of intergovernmental organizations including the G20,[209] the SCO,[210] the BRICS,[211] the East Asia Summit,[212] and the APEC.[213] China was also a former member and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, and still considers itself an advocate for developing countries.[214]

The PRC officially maintains the one-China principle, which holds the view that there is only one sovereign state in the name of China, represented by the PRC, and that Taiwan is part of that China.[215] The unique status of Taiwan has led to countries recognizing the PRC to maintain unique "one-China policies" that differ from each other; some countries explicitly recognize the PRC's claim over Taiwan, while others, including the U.S. and Japan, only acknowledge the claim.[215] Chinese officials have protested on numerous occasions when foreign countries have made diplomatic overtures to Taiwan,[216] especially in the matter of armament sales.[217] Most countries have switched recognition from the ROC to the PRC since the latter replaced the former in the UN in 1971.[218]

Much of current Chinese foreign policy is reportedly based on Premier Zhou Enlai's Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, and is also driven by the concept of "harmony without uniformity", which encourages diplomatic relations between states despite ideological differences.[219] This policy may have led China to support or maintain close ties with states that are regarded as dangerous and repressive by Western nations, such as Sudan,[220] North Korea and Iran.[221] China's close relationship with Myanmar has involved support for its ruling governments as well as for its ethnic rebel groups,[222] including the Arakan Army.[223] China has a close political, economic and military relationship with Russia,[224] and the two states often vote in unison in the UN Security Council.[225][226][227] China's relationship with the United States is complex, and includes deep trade ties but significant political differences.[228]

Since the early 2000s, China has followed a policy of engaging with African nations for trade and bilateral co-operation.[229][230][231] It maintains extensive and highly diversified trade links with the European Union, and became its largest trading partner for goods.[232] China is increasing its influence in Central Asia[233] and South Pacific.[234] The country has strong trade ties with ASEAN countries[235] and major South American economies,[236] and is the largest trading partner of Brazil, Chile, Peru, Uruguay, Argentina, and several others.[237]

In 2013, China initiated the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a large global infrastructure building initiative with funding on the order of $50–100 billion per year.[238] BRI could be one of the largest development plans in modern history.[239] It has expanded significantly over the last six years and, as of April 2020[update], includes 138 countries and 30 international organizations. In addition to intensifying foreign policy relations, the focus is particularly on building efficient transport routes, especially the maritime Silk Road with its connections to East Africa and Europe. However many loans made under the program are unsustainable and China has faced a number of calls for debt relief from debtor nations.[240][241]

Military

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is considered one of the world's most powerful militaries and has rapidly modernized in the recent decades.[242] It has also been accused of technology theft by some countries.[243][244][245] Since 2024, it consists of four services: the Ground Force (PLAGF), the Navy (PLAN), the Air Force (PLAAF) and the Rocket Force (PLARF). It also has four independent arms: the Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, the Information Support Force, and the Joint Logistics Support Force, the first three of which were split from the disbanded Strategic Support Force (PLASSF).[246] Its nearly 2.2 million active duty personnel is the largest in the world. The PLA holds the world's third-largest stockpile of nuclear weapons,[247][248] and the world's second-largest navy by tonnage.[249] China's official military budget for 2023 totalled US$224 billion (1.55 trillion Yuan), the second-largest in the world, though SIPRI estimates that its real expenditure that year was US$296 billion, making up 12% of global military spending and accounting for 1.7% of the country's GDP.[250] According to SIPRI, its military spending from 2012 to 2021 averaged US$215 billion per year or 1.7 per cent of GDP, behind only the United States at US$734 billion per year or 3.6 per cent of GDP.[251] The PLA is commanded by the Central Military Commission (CMC) of the party and the state; though officially two separate organizations, the two CMCs have identical membership except during leadership transition periods and effectively function as one organization. The chairman of the CMC is the commander-in-chief of the PLA.[252]

Sociopolitical issues and human rights

The situation of human rights in China has attracted significant criticism from foreign governments, foreign press agencies, and non-governmental organizations, alleging widespread civil rights violations such as detention without trial, forced confessions, torture, restrictions of fundamental rights, and excessive use of the death penalty.[190][253] Since its inception, Freedom House has ranked China as "not free" in its Freedom in the World survey,[190] while Amnesty International has documented significant human rights abuses.[253] The Chinese constitution states that the "fundamental rights" of citizens include freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to a fair trial, freedom of religion, universal suffrage, and property rights. However, in practice, these provisions do not afford significant protection against criminal prosecution by the state.[254][255] China has limited protections regarding LGBT rights.[256]

Although some criticisms of government policies and the ruling CCP are tolerated, censorship of political speech and information are amongst the harshest in the world and routinely used to prevent collective action.[257] China also has the most comprehensive and sophisticated Internet censorship regime in the world, with numerous websites being blocked.[258] The government suppresses popular protests and demonstrations that it considers a potential threat to "social stability".[259] China additionally uses a massive espionage network of cameras, facial recognition software, sensors, and surveillance of personal technology as a means of social control of persons living in the country.[260]

China is regularly accused of large-scale repression and human rights abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang,[262][263][264] where significant numbers of ethnic minorities reside, including violent police crackdowns and religious suppression.[265][266] Since 2017, the Chinese government has been engaged in a harsh crackdown in Xinjiang, with around one million Uyghurs and other ethnic and religion minorities being detained in internment camps aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[267] According to Western reports, political indoctrination, torture, physical and psychological abuse, forced sterilization, sexual abuse, and forced labor are common in these facilities.[268] According to a 2020 Foreign Policy report, China's treatment of Uyghurs meets the UN definition of genocide,[269] while a separate UN Human Rights Office report said they could potentially meet the definitions for crimes against humanity.[270] The Chinese authorities have also cracked down on dissent in Hong Kong, especially after the passage of a national security law in 2020.[271]

In 2017 and 2020, the Pew Research Center ranked the severity of Chinese government restrictions on religion as being among the world's highest, despite ranking religious-related social hostilities in China as low in severity.[272][273] The Global Slavery Index estimated that in 2016 more than 3.8 million people (0.25% of the population) were living in "conditions of modern slavery", including victims of human trafficking, forced labor, forced marriage, child labor, and state-imposed forced labor. The state-imposed re-education through labor (laojiao) system was formally abolished in 2013, but it is not clear to what extent its practices have stopped.[274] The much larger reform through labor (laogai) system includes labor prison factories, detention centers, and re-education camps; the Laogai Research Foundation has estimated in June 2008 that there were nearly 1,422 of these facilities, though it cautioned that this number was likely an underestimate.[275]

Public views of government

Political concerns in China include the growing gap between rich and poor and government corruption.[276] Nonetheless, international surveys show the Chinese public have a high level of satisfaction with their government.[201]: 137 These views are generally attributed to the material comforts and security available to large segments of the Chinese populace as well as the government's attentiveness and responsiveness.[201] : 136 According to the World Values Survey (2022), 91% of Chinese respondents have significant confidence in their government.[201]: 13 A Harvard University survey published in July 2020 found that citizen satisfaction with the government had increased since 2003, also rating China's government as more effective and capable than ever in the survey's history.[277]

Economy

China has the world's second-largest economy in terms of nominal GDP,[278] and the world's largest in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP).[279] As of 2022[update], China accounts for around 18% of the global economy by nominal GDP.[280] China is one of the world's fastest-growing major economies,[281] with its economic growth having been almost consistently above 6 percent since the introduction of economic reforms in 1978.[282] According to the World Bank, China's GDP grew from $150 billion in 1978 to $17.96 trillion by 2022.[283] It ranks at 64th at nominal GDP per capita, making it an upper-middle income country.[284] Of the world's 500 largest companies, 135 are headquartered in China.[285] As of at least 2024, China has the world's second-largest equity markets and futures markets, as well as the third-largest bond market.[286]: 153

China was one of the world's foremost economic powers throughout the arc of East Asian and global history. The country had one of the largest economies in the world for most of the past two millennia,[287] during which it has seen cycles of prosperity and decline.[54][288] Since economic reforms began in 1978, China has developed into a highly diversified economy and one of the most consequential players in international trade. Major sectors of competitive strength include manufacturing, retail, mining, steel, textiles, automobiles, energy generation, green energy, banking, electronics, telecommunications, real estate, e-commerce, and tourism. China has three out of the ten largest stock exchanges in the world[289]—Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen—that together have a market capitalization of over $15.9 trillion, as of October 2020[update].[290] China has four (Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shenzhen) out of the world's top ten most competitive financial centers, which is more than any other country in the 2020 Global Financial Centres Index.[291]

Modern-day China is often described as an example of state capitalism or party-state capitalism.[293][294] The state dominates in strategic "pillar" sectors such as energy production and heavy industries, but private enterprise has expanded enormously, with around 30 million private businesses recorded in 2008.[295][296][297] According to official statistics, privately owned companies constitute more than 60% of China's GDP.[298]

China has been the world's largest manufacturing nation since 2010, after overtaking the U.S., which had been the largest for the previous hundred years.[299][300] China has also been the second-largest in high-tech manufacturing country since 2012, according to US National Science Foundation.[301] China is the second-largest retail market after the United States.[302] China leads the world in e-commerce, accounting for over 37% of the global market share in 2021.[303] China is the world's leader in electric vehicle consumption and production, manufacturing and buying half of all the plug-in electric cars (BEV and PHEV) in the world as of 2022[update].[304] China is also the leading producer of batteries for electric vehicles as well as several key raw materials for batteries.[305]

Tourism

China received 65.7 million international visitors in 2019,[306] and in 2018 was the fourth-most-visited country in the world.[306] It also experiences an enormous volume of domestic tourism; Chinese tourists made an estimated 6 billion travels within the country in 2019.[307] China hosts the world's second-largest number of World Heritage Sites (56) after Italy, and is one of the most popular tourist destinations (first in the Asia-Pacific).

Wealth

China accounted for 17.9% of the world's total wealth in 2021, second highest in the world after the U.S.[308] China brought more people out of extreme poverty than any other country in history[309][310]—between 1978 and 2018, China reduced extreme poverty by 800 million.[201]: 23 From 1990 to 2018, the proportion of the Chinese population living with an income of less than $1.90 per day (2011 PPP) decreased from 66.3% to 0.3%, the share living with an income of less than $3.20 per day from 90.0% to 2.9%, and the share living with an income of less than $5.50 per day decreased from 98.3% to 17.0%.[311]

From 1978 to 2018, the average standard of living multiplied by a factor of twenty-six.[312] Wages in China have grown significantly in the last 40 years—real (inflation-adjusted) wages grew seven-fold from 1978 to 2007.[313] Per capita incomes have also risen significantly – when the PRC was founded in 1949, per capita income in China was one-fifth of the world average; per capita incomes now equal the world average itself.[312] China's development is highly uneven. Its major cities and coastal areas are far more prosperous compared to rural and interior regions.[314] It has a high level of economic inequality,[315] which has increased quickly after the economic reforms,[316] though has decreased significantly in the 2010s.[317] In 2021, China's Gini coefficient was 0.357, according to the World Bank.[12]

As of March 2024[update], China was second in the world, after the U.S., in total number of billionaires and total number of millionaires, with 473 Chinese billionaires[318] and 6.2 million millionaires.[308] In 2019, China overtook the U.S. as the home to the highest number of people who have a net personal wealth of at least $110,000, according to the global wealth report by Credit Suisse.[319][320] China had 85 female billionaires as of January 2021[update], two-thirds of the global total.[321] China has had the world's largest middle-class population since 2015;[322] the middle-class grew to 500 million by 2024.[323]

China in the global economy

China has been a member of the WTO since 2001 and is the world's largest trading power.[324] By 2016, China was the largest trading partner of 124 countries.[325] China became the world's largest trading nation in 2013 by the sum of imports and exports, as well as the world's largest commodity importer, accounting for roughly 45% of maritime's dry-bulk market.[326][327]

China's foreign exchange reserves reached US$3.246 trillion as of March 2024[update], making its reserves by far the world's largest.[328] In 2022, China was amongst the world's largest recipient of inward foreign direct investment (FDI), attracting $180 billion, though most of these were speculated to be from Hong Kong.[329] In 2021, China's foreign exchange remittances were $US53 billion making it the second-largest recipient of remittances in the world.[330] China also invests abroad, with a total outward FDI of $147.9 billion in 2023,[331] and a number of major takeovers of foreign firms by Chinese companies.[332]

Economists have argued that the renminbi is undervalued, due to currency intervention from the Chinese government, giving China an unfair trade advantage.[333] China has also been widely criticized for manufacturing large quantities of counterfeit goods.[334][335] The U.S. government has also alleged that China does not respect intellectual property (IP) rights and steals IP through espionage operations.[336] In 2020, Harvard University's Economic Complexity Index ranked complexity of China's exports 17th in the world, up from 24th in 2010.[337]

The Chinese government has promoted the internationalization of the renminbi in order to wean off of its dependence on the U.S. dollar as a result of perceived weaknesses of the international monetary system.[338] The renminbi is a component of the IMF's special drawing rights and the world's fourth-most traded currency as of 2023[update].[339] However, partly due to capital controls that make the renminbi fall short of being a fully convertible currency, it remains far behind the Euro, the U.S. Dollar and the Japanese Yen in international trade volumes.[340]

Science and technology

Historical

China was a world leader in science and technology until the Ming dynasty.[341] Ancient and medieval Chinese discoveries and inventions, such as papermaking, printing, the compass, and gunpowder (the Four Great Inventions), became widespread across East Asia, the Middle East and later Europe. Chinese mathematicians were the first to use negative numbers.[342][343] By the 17th century, the Western World surpassed China in scientific and technological advancement.[344] The causes of this early modern Great Divergence continue to be debated by scholars.[345]

After repeated military defeats by the European colonial powers and Imperial Japan in the 19th century, Chinese reformers began promoting modern science and technology as part of the Self-Strengthening Movement. After the Communists came to power in 1949, efforts were made to organize science and technology based on the model of the Soviet Union, in which scientific research was part of central planning.[346] After Mao's death in 1976, science and technology were promoted as one of the Four Modernizations,[347] and the Soviet-inspired academic system was gradually reformed.[348]

Modern era

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, China has made significant investments in scientific research[349] and is quickly catching up with the U.S. in R&D spending.[350][351] China officially spent around 2.6% of its GDP on R&D in 2023, totaling to around $458.5 billion.[352] According to the World Intellectual Property Indicators, China received more applications than the U.S. did in 2018 and 2019 and ranked first globally in patents, utility models, trademarks, industrial designs, and creative goods exports in 2021.[353][354][355] It was ranked 11th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, a considerable improvement from its rank of 35th in 2013.[356][357][358] Chinese supercomputers ranked among the fastest in the world.[359][u] Its efforts to develop the most advanced semiconductors and jet engines have seen delays and setbacks.[360][361]

China is developing its education system with an emphasis on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).[362] Its academic publication apparatus became the world's largest publisher of scientific papers in 2016.[363][364][365] In 2022, China overtook the US in the Nature Index, which measures the share of published articles in leading scientific journals.[366][367]

Space program

The Chinese space program started in 1958 with some technology transfers from the Soviet Union. However, it did not launch the nation's first satellite until 1970 with the Dong Fang Hong I, which made China the fifth country to do so independently.[368]

In 2003, China became the third country in the world to independently send humans into space with Yang Liwei's spaceflight aboard Shenzhou 5. As of 2023, eighteen Chinese nationals have journeyed into space, including two women. In 2011, China launched its first space station testbed, Tiangong-1.[369] In 2013, a Chinese robotic rover Yutu successfully touched down on the lunar surface as part of the Chang'e 3 mission.[370]

In 2019, China became the first country to land a probe—Chang'e 4—on the far side of the Moon.[371] In 2020, Chang'e 5 successfully returned Moon samples to the Earth, making China the third country to do so independently.[372] In 2021, China became the third country to land a spacecraft on Mars and the second one to deploy a rover (Zhurong) on Mars.[373] China completed its own modular space station, the Tiangong, in low Earth orbit on 3 November 2022.[374][375][376] On 29 November 2022, China performed its first in-orbit crew handover aboard the Tiangong.[377][378]

In May 2023, China announced a plan to land humans on the Moon by 2030.[379] To that end, China currently is developing a lunar-capable super-heavy launcher, the Long March 10, a new crewed spacecraft, and a crewed lunar lander.[380][381]

China sent Chang'e 6 on 3 May 2024, which conducted the first lunar sample return from Apollo Basin on the far side of the Moon.[382] This is China's second lunar sample return mission, the first was achieved by Chang'e 5 from the lunar near side 4 years ago.[383] It also carried a Chinese rover called Jinchan to conduct infrared spectroscopy of lunar surface and imaged Chang'e 6 lander on lunar surface.[384] The lander-ascender-rover combination was separated with the orbiter and returner before landing on 1 June 2024, at 22:23 UTC. It landed on the Moon's surface on 1 June 2024.[385][386] The ascender was launched back to lunar orbit on 3 June 2024, at 23:38 UTC, carrying samples collected by the lander, which later completed another robotic rendezvous, before docking in lunar orbit. The sample container was then transferred to the returner, which landed on Inner Mongolia in June 2024, completing China's far side extraterrestrial sample return mission.

Infrastructure

After a decades-long infrastructural boom,[387] China has produced numerous world-leading infrastructural projects: it has the largest high-speed rail network,[388] the most supertall skyscrapers,[389] the largest power plant (the Three Gorges Dam),[390] and a global satellite navigation system with the largest number of satellites.[391]

Telecommunications

China is the largest telecom market in the world and currently has the largest number of active cellphones of any country, with over 1.7 billion subscribers, as of February 2023[update]. It has the largest number of internet and broadband users, with over 1.09 billion Internet users as of December 2023[update][392]—equivalent to around 77.5% of its population.[393] By 2018, China had more than 1 billion 4G users, accounting for 40% of world's total.[394] China is making rapid advances in 5G—by late 2018, China had started large-scale and commercial 5G trials.[395] As of December 2023[update], China had over 810 million 5G users and 3.38 million base stations installed.[396]

China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom, are the three large providers of mobile and internet in China. China Telecom alone served more than 145 million broadband subscribers and 300 million mobile users; China Unicom had about 300 million subscribers; and China Mobile, the largest of them all, had 925 million users, as of 2018[update].[397] Combined, the three operators had over 3.4 million 4G base-stations in China.[398] Several Chinese telecommunications companies, most notably Huawei and ZTE, have been accused of spying for the Chinese military.[399]

China has developed its own satellite navigation system, dubbed BeiDou, which began offering commercial navigation services across Asia in 2012[400] as well as global services by the end of 2018.[401] Beidou followed GPS and GLONASS as the third completed global navigation satellite.[402]

Transport

Since the late 1990s, China's national road network has been significantly expanded through the creation of a network of national highways and expressways. In 2022, China's highways had reached a total length of 177,000 km (110,000 mi), making it the longest highway system in the world.[403] China has the world's largest market for automobiles,[404][405] having surpassed the United States in both auto sales and production. The country is the world's largest exporter of cars by number as of 2023.[406][407] A side-effect of the rapid growth of China's road network has been a significant rise in traffic accidents.[408] In urban areas, bicycles remain a common mode of transport, despite the increasing prevalence of automobiles – as of 2023[update], there are approximately 200 million bicycles in China.[409]

China's railways, which are operated by the state-owned China State Railway Group Company, are among the busiest in the world, handling a quarter of the world's rail traffic volume on only 6 percent of the world's tracks in 2006.[410] As of 2023[update], the country had 159,000 km (98,798 mi) of railways, the second-longest network in the world.[411] The railways strain to meet enormous demand particularly during the Chinese New Year holiday, when the world's largest annual human migration takes place.[412] China's high-speed rail (HSR) system started construction in the early 2000s. By the end of 2023, high speed rail in China had reached 45,000 kilometers (27,962 miles) of dedicated lines alone, making it the longest HSR network in the world.[413] Services on the Beijing–Shanghai, Beijing–Tianjin, and Chengdu–Chongqing lines reach up to 350 km/h (217 mph), making them the fastest conventional high speed railway services in the world. With an annual ridership of over 2.3 billion passengers in 2019, it is the world's busiest.[414] The network includes the Beijing–Guangzhou high-speed railway, the single longest HSR line in the world, and the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway, which has three of longest railroad bridges in the world.[415] The Shanghai maglev train, which reaches 431 km/h (268 mph), is the fastest commercial train service in the world.[416] Since 2000, the growth of rapid transit systems in Chinese cities has accelerated.[417] As of December 2023[update], 55 Chinese cities have urban mass transit systems in operation.[418] As of 2020[update], China boasts the five longest metro systems in the world with the networks in Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Chengdu and Shenzhen being the largest.

The civil aviation industry in China is mostly state-dominated, with the Chinese government retaining a majority stake in the majority of Chinese airlines. The top three airlines in China, which collectively made up 71% of the market in 2018, are all state-owned. Air travel has expanded rapidly in the last decades, with the number of passengers increasing from 16.6 million in 1990 to 551.2 million in 2017.[419] China had approximately 259 airports in 2024.[420]

China has over 2,000 river and seaports, about 130 of which are open to foreign shipping.[421] Of the fifty busiest container ports, 15 are located in China, of which the busiest is the Port of Shanghai, also the busiest port in the world.[422] The country's inland waterways are the world's sixth-longest, and total 27,700 km (17,212 mi).[423]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation infrastructure in China is facing challenges such as rapid urbanization, as well as water scarcity, contamination, and pollution.[424] According to the Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation, about 36% of the rural population in China still did not have access to improved sanitation in 2015.[425][needs update] The ongoing South–North Water Transfer Project intends to abate water shortage in the north.[426]

Demographics

The 2020 Chinese census recorded the population as approximately 1,411,778,724. About 17.95% were 14 years old or younger, 63.35% were between 15 and 59 years old, and 18.7% were over 60 years old.[427] Between 2010 and 2020, the average population growth rate was 0.53%.[427]

Given concerns about population growth, China implemented a two-child limit during the 1970s, and, in 1979, began to advocate for an even stricter limit of one child per family. Beginning in the mid-1980s, however, given the unpopularity of the strict limits, China began to allow some major exemptions, particularly in rural areas, resulting in what was actually a "1.5"-child policy from the mid-1980s to 2015; ethnic minorities were also exempt from one-child limits.[428] The next major loosening of the policy was enacted in December 2013, allowing families to have two children if one parent is an only child.[429] In 2016, the one-child policy was replaced in favor of a two-child policy.[430] A three-child policy was announced on 31 May 2021, due to population aging,[430] and in July 2021, all family size limits as well as penalties for exceeding them were removed.[431] In 2023, the total fertility rate was reported to be 1.09, ranking among the lowest in the world.[432] In 2023, National Bureau of Statistics estimated that the population fell 850,000 from 2021 to 2022, the first decline since 1961.[433]

According to one group of scholars, one-child limits had little effect on population growth[434] or total population size.[435] However, these scholars have been challenged.[436] The policy, along with traditional preference for boys, may have contributed to an imbalance in the sex ratio at birth.[437][438] The 2020 census found that males accounted for 51.2% of the total population.[439] However, China's sex ratio is more balanced than it was in 1953, when males accounted for 51.8% of the population.[440]

The cultural preference for male children, combined with the one-child policy, led to an excess of female child orphans in China, and in the 1990s through around 2007, there was an active stream of adoptions of (mainly female) babies by American and other foreign parents.[441] However, increased restrictions by the Chinese Government slowed foreign adoptions significantly in 2007 and again in 2015.[442]

Urbanization

China has urbanized significantly in recent decades. The percent of the country's population living in urban areas increased from 20% in 1980 to over 66% in 2023.[443][444][445] China has over 160 cities with a population of over one million,[446] including the 17 megacities as of 2021[update][447][448] (cities with a population of over 10 million) of Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Tianjin, Xi'an, Suzhou, Zhengzhou, Wuhan, Hangzhou, Linyi, Shijiazhuang, Dongguan, Qingdao and Changsha.[449] The total permanent population of Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing and Chengdu is above 20 million.[450] Shanghai is China's most populous urban area[451][452] while Chongqing is its largest city proper, the only city in China with a permanent population of over 30 million.[453] The figures in the table below are from the 2020 census, and are only estimates of the urban populations within administrative city limits; a different ranking exists for total municipal populations. The large "floating populations" of migrant workers make conducting censuses in urban areas difficult;[454] the figures below include only long-term residents.

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Shanghai  Beijing |

1 | Shanghai | SH | 24,281,400 | 11 | Hong Kong | HK | 7,448,900 |  Guangzhou  Shenzhen |

| 2 | Beijing | BJ | 19,164,000 | 12 | Zhengzhou | HA | 7,179,400 | ||

| 3 | Guangzhou | GD | 13,858,700 | 13 | Nanjing | JS | 6,823,500 | ||

| 4 | Shenzhen | GD | 13,438,800 | 14 | Xi'an | SN | 6,642,100 | ||

| 5 | Tianjin | TJ | 11,744,400 | 15 | Jinan | SD | 6,409,600 | ||

| 6 | Chongqing | CQ | 11,488,000 | 16 | Shenyang | LN | 5,900,000 | ||

| 7 | Dongguan | GD | 9,752,500 | 17 | Qingdao | SD | 5,501,400 | ||

| 8 | Chengdu | SC | 8,875,600 | 18 | Harbin | HL | 5,054,500 | ||

| 9 | Wuhan | HB | 8,652,900 | 19 | Hefei | AH | 4,750,100 | ||

| 10 | Hangzhou | ZJ | 8,109,000 | 20 | Changchun | JL | 4,730,900 | ||

- ^ Population of Hong Kong as of 2018 estimate[456]

- ^ The data of Chongqing in the list is the data of "Metropolitan Developed Economic Area", which contains two parts: "City Proper" and "Metropolitan Area". The "City proper" are consist of 9 districts: Yuzhong, Dadukou, Jiangbei, Shapingba, Jiulongpo, Nan'an, Beibei, Yubei, & Banan, has the urban population of 5,646,300 as of 2018. And the "Metropolitan Area" are consist of 12 districts: Fuling, Changshou, Jiangjin, Hechuan, Yongchuan, Nanchuan, Qijiang, Dazu, Bishan, Tongliang, Tongnan, & Rongchang, has the urban population of 5,841,700.[457] Total urban population of all 26 districts of Chongqing are up to 15,076,600.

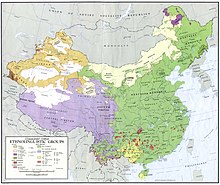

Ethnic groups

China legally recognizes 56 distinct ethnic groups, who comprise the Zhonghua minzu. The largest of these nationalities are the Han Chinese, who constitute more than 91% of the total population.[427] The Han Chinese – the world's largest single ethnic group[458] – outnumber other ethnic groups in every place excluding Tibet, Xinjiang,[459] Linxia,[460] and autonomous prefectures like Xishuangbanna.[461] Ethnic minorities account for less than 10% of the population of China, according to the 2020 census.[427] Compared with the 2010 population census, the Han population increased by 60,378,693 persons, or 4.93%, while the population of the 55 national minorities combined increased by 11,675,179 persons, or 10.26%.[427] The 2020 census recorded a total of 845,697 foreign nationals living in mainland China.[462]

Languages

There are as many as 292 living languages in China.[463] The languages most commonly spoken belong to the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, which contains Mandarin (spoken by 80% of the population),[464][465] and other varieties of Chinese language: Jin, Wu, Min, Hakka, Yue, Xiang, Gan, Hui, Ping and unclassified Tuhua (Shaozhou Tuhua and Xiangnan Tuhua).[466] Languages of the Tibeto-Burman branch, including Tibetan, Qiang, Naxi and Yi, are spoken across the Tibetan and Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau. Other ethnic minority languages in southwestern China include Zhuang, Thai, Dong and Sui of the Tai-Kadai family, Miao and Yao of the Hmong–Mien family, and Wa of the Austroasiatic family. Across northeastern and northwestern China, local ethnic groups speak Altaic languages including Manchu, Mongolian and several Turkic languages: Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Salar and Western Yugur.[467][468] Korean is spoken natively along the border with North Korea. Sarikoli, the language of Tajiks in western Xinjiang, is an Indo-European language. Taiwanese indigenous peoples, including a small population on the mainland, speak Austronesian languages.[469]

Standard Mandarin, a variety of Mandarin based on the Beijing dialect, is the national language and de facto official language of China.[2] It is used as a lingua franca between people of different linguistic backgrounds.[470][471] In the autonomous regions of China, other languages may also serve as a lingua franca, such as Uyghur in Xinjiang, where governmental services in Uyghur are constitutionally guaranteed.[472][473]

Religion

[474][475][476][477]

■ Chinese folk religion (including Confucianism, Taoism, and groups of Chinese Buddhism)

■ Buddhism tout court

■ Islam

■ Ethnic minorities' indigenous religions

■ Mongolian folk religion

■ Northeast China folk religion influenced by Tungus and Manchu shamanism; widespread Shanrendao

Freedom of religion is guaranteed by China's constitution (Chapter 2, Article 36), although religious organizations that lack official approval can be subject to state persecution.[184] The government of the country is officially atheist. Religious affairs and issues in the country are overseen by the National Religious Affairs Administration, under the United Front Work Department.[478]