Pethidine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Demerol, others |

| Other names | Meperidine (USAN US) |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High |

| Addiction liability | High[1] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, intrathecal,[2] subcutaneous, epidural[3] |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50–60% (Oral), 80–90% (Oral, in cases of hepatic impairment) |

| Protein binding | 65–75% |

| Metabolism | Liver: CYP2B6, CYP3A4, CYP2C19, Carboxylesterase 1 |

| Metabolites | • Norpethidine • Pethidinic Acid • others |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5–4 hours, 7–11 hours (liver disease) |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.299 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H21NO2 |

| Molar mass | 247.338 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

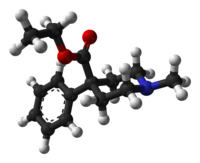

Pethidine, also known as meperidine and sold under the brand name Demerol among others, is a fully synthetic opioid pain medication of the phenylpiperidine class.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Synthesized in 1938[11] as a potential anticholinergic agent by the German chemist Otto Eisleb, its analgesic properties were first recognized by Otto Schaumann while working for IG Farben, in Germany.[12] Pethidine is the prototype of a large family of analgesics including the pethidine 4-phenylpiperidines (e.g., piminodine, anileridine), the prodines (e.g., alphaprodine, MPPP), bemidones (e.g., ketobemidone), and others more distant, including diphenoxylate and analogues.[13]

Pethidine is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pain, and is delivered as a hydrochloride salt in tablets, as a syrup, or by intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous injection. For much of the 20th century, pethidine was the opioid of choice for many physicians; in 1975, 60% of doctors prescribed it for acute pain and 22% for chronic severe pain.[14]

It was patented in 1937 and approved for medical use in 1943.[15] Compared with morphine, pethidine was considered to be safer, carry a lower risk of addiction, and to be superior in treating the pain associated with biliary spasm or renal colic due to its assumed anticholinergic effects.[7] These were later discovered to be inaccurate assumptions, as it carries an equal risk of addiction, possesses no advantageous effects on biliary spasm or renal colic compared to other opioids. Due to the neurotoxicity of its metabolite, norpethidine, it is more toxic than other opioids—especially during long-term use.[7] The norpethidine metabolite was found to have serotonergic effects, so pethidine could, unlike most opioids, increase the risk of triggering serotonin syndrome.[7][8]

Medical uses

[edit]Pethidine is the most widely used opioid in labour and delivery.[16] It has fallen out of favour in some countries, such as the United States, in favour of other opioids, due to its potential drug interactions, especially with serotonergics, and its neurotoxic metabolite, norpethidine.[10] It is still commonly used in the United Kingdom and New Zealand,[17] and was the preferred opioid in the United Kingdom for use during labour, but has been superseded somewhat by other strong semi-synthetic opioids (e.g. hydromorphone) to avoid serotonin interactions since the mid-2000s.[18]

Pethidine is the preferred painkiller for diverticulitis, because it decreases intestinal intraluminal pressure.[19] Pethidine is the preferred drug for the management of shivering during therapeutic hypothermia, as it provides the greatest reduction in the shivering threshold.[20]

Before 2003, it was on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[21][22]

Adverse effects

[edit]The adverse effects of pethidine administration are primarily those of the opioids as a class: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, diaphoresis, urinary retention, and constipation. Due to moderate stimulant effects mediated by pethidine's dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, sedation is less likely compared to other opioids. Unlike other opioids, it does not cause miosis because of its anticholinergic properties. Overdose can cause muscle flaccidity, respiratory depression, obtundation, psychosis, cold and clammy skin, hypotension, and coma.[23][24]

A narcotic antagonist such as naloxone is indicated to reverse respiratory depression and other effects of pethidine. Serotonin syndrome has occurred in patients receiving concurrent antidepressant therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or other medication types (see Interactions below). Convulsive seizures sometimes observed in patients receiving parenteral pethidine on a chronic basis have been attributed to accumulation in plasma of the metabolite norpethidine (normeperidine). Fatalities have occurred following either oral or intravenous pethidine overdose.[25][26]

Interactions

[edit]Pethidine has serious interactions that can be dangerous with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., furazolidone, isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, procarbazine, selegiline, tranylcypromine). Such patients may suffer agitation, delirium, headache, convulsions, and/or hyperthermia. Fatal interactions have been reported including the death of Libby Zion.[27]

Seizures may develop when tramadol is given intravenously following, or with, pethidine.[28] It can interact as well with SSRIs and other antidepressants, antiparkinson agents, migraine therapy, stimulants and other agents causing serotonin syndrome. It is thought to be caused by an increase in cerebral serotonin concentrations. It is probable that pethidine can also interact with a number of other medications, including muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, and ethanol.

Mechanism of action

[edit]Like morphine, pethidine exerts its analgesic effects by acting as an agonist at the μ-opioid receptor.[29]

Pethidine is often employed in the treatment of postanesthetic shivering. The pharmacologic mechanism of this antishivering effect is not fully understood,[30] but it may involve the stimulation of κ-opioid receptors.[31]

Pethidine has structural similarities to atropine and other tropane alkaloids and may have some of their effects and side effects.[32] In addition to these opioidergic and anticholinergic effects, it has local anesthetic activity related to its interactions with sodium ion channels.

Pethidine's apparent in vitro efficacy as an antispasmodic agent is due to its local anesthetic effects. It does not have antispasmodic effects in vivo.[33] Pethidine also has stimulant effects mediated by its inhibition of the dopamine transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET). Because of its DAT inhibitory action, pethidine will substitute for cocaine in animals trained to discriminate cocaine from saline.[34]

Several analogs of pethidine such as 4-fluoropethidine have been synthesized that are potent inhibitors of the reuptake of the monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine via DAT and NET.[35][36] It has also been associated with cases of serotonin syndrome, suggesting some interaction with serotonergic neurons, but the relationship has not been definitively demonstrated.[34][36][37][38]

It is more lipid-soluble than morphine, resulting in a faster onset of action. Its duration of clinical effect is 120–150 minutes, although it is typically administered at 4– to 6-hour intervals. Pethidine has been shown to be less effective than morphine, diamorphine, or hydromorphone at easing severe pain, or pain associated with movement or coughing.[34][36][38]

Like other opioid drugs, pethidine has the potential to cause physical dependence or addiction. The especially severe side effects unique to pethidine among opioids—serotonin syndrome, seizures, delirium, dysphoria, tremor—are primarily or entirely due to the action of its metabolite, norpethidine.[36][38]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Pethidine is quickly hydrolysed in the liver to pethidinic acid and is also demethylated to norpethidine, which has half the analgesic activity of pethidine but a longer elimination half-life (8–12 hours);[39] accumulating with regular administration, or in kidney failure. Norpethidine is toxic and has convulsant and hallucinogenic effects.

The toxic effects mediated by the metabolites cannot be countered with opioid receptor antagonists such as naloxone or naltrexone, and are probably primarily due to norpethidine's anticholinergic activity probably due to its structural similarity to atropine, though its pharmacology has not been thoroughly explored. The neurotoxicity of pethidine's metabolites is a unique feature of pethidine compared to other opioids. Pethidine's metabolites are further conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted into the urine.

Recreational use

[edit]Trends

[edit]In data from the U.S. Drug Abuse Warning Network, mentions of hazardous or harmful use of pethidine declined between 1997 and 2002, in contrast to increases for fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, and oxycodone.[40] The number of dosage units of pethidine reported lost or stolen in the U.S. increased 16.2% between 2000 and 2003, from 32,447 to 37,687.[41]

This article uses the terms "hazardous use", "harmful use", and "dependence" in accordance with Lexicon of alcohol and drug[42] terms, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994.[43] In WHO usage, the first two terms replace the term "abuse" and the third term replaces the term "addiction".[43][34]

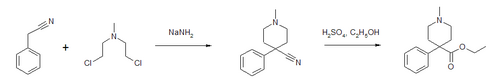

Synthesis

[edit]Pethidine can be produced in a two-step synthesis. The first step is reaction of benzyl cyanide and chlormethine in the presence of sodium amide to form a piperidine ring. The nitrile is then converted to an ester.[44]

Control

[edit]Pethidine is in Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act 1970 of the United States as a Narcotic with ACSCN 9230 with a 6250 kilo aggregate manufacturing quota as of 2014. The free base conversion ratio for salts includes 0.87 for the hydrochloride and 0.84 for the hydrobromide. The A, B, and C intermediates in production of pethidine are also controlled, with ACSCN being 9232 for A (with a 6 gram quota) and 9233 being B (quota of 11 grams) and 9234 being C (6 gram quota).[45] It is listed under the Single Convention for the Control of Narcotic Substances 1961 and is controlled in most countries in the same fashion as is morphine.

Society and culture

[edit]In John D. MacDonalds 's book "Dress Her in Indigo" (1969) one of the protagonists speaks of thinking of killing an immobilized enemy of hers by injecting him with meperedine which was left over from a husband who used it while terminally ill.

In Raymond Chandler's novel The Long Goodbye (1953), in response to "How is Mrs. Wade?", police Lieutenant Bernie Ohls answers, "Too relaxed. She must have grabbed some pills. There's a dozen kinds up there -- even demerol. That's bad stuff."

Harold Shipman was addicted to pethidine at one stage, convicted of forging prescriptions to obtain it, fined £500 and briefly attended a drug rehabilitation clinic.[46][47]

Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen suffered a lifelong addiction to pethidine after her husband, a doctor, had injected her with Demerol as a painkiller for an illegal abortion in 1944.[48]

Pethidine is referenced by its brand name Demerol in the song "Morphine" by singer Michael Jackson on his 1997 album Blood on the Dance Floor: HIStory in the Mix.[49] Pethidine was one of several prescription drugs which Michael Jackson was addicted to at the time and the singer describes this in the lyrics of the song with phrases such as "Relax/This won't hurt you" and "Yesterday you had his trust/Today he's taking twice as much".[50]

Pethidine is referenced in the television show Broadchurch, season 2, episode 3, as it was given to the character Beth after she has her baby.

In the 1987 Malayalam movie, Amrutham Gamaya, Mohanlal's character, Dr. P.K. Haridas injects pethidine in himself and gets addicted to it.

A doctor in the TV show Call the Midwife becomes addicted to pethidine.[51]

In William Gibson's book Neuromancer, one of the characters say '"A mixture of cocaine and meperidine, yes." The Armenian went back to the conversation he was having with the Sanyo. "Demerol, they used to call that," said the Finn.'[52]

South Carolina-based modern rock group Crossfade mentions Demerol in the lyrics of their 2004 song, "Dead Skin".

In Korean drama Punch (TV series), main character Park Jung-hwan is illegally given Demerol by his doctor in exchange for legal counseling.

In the episode "The Fight" of the TV show Parks and Recreation, some characters become intoxicated on a mixed drink called Snake Juice. The character Ann (Rashida Jones), who is a nurse, asks, "What the hell is in Snake Juice? Demerol?"

In David Foster Wallace's book Infinite Jest, one of the main characters, Don Gately, is a Demerol addict in recovery.

See also

[edit]- Libby Zion Law (a case involving phenelzine and pethidine)

References

[edit]- ^ Bonewit-West K, Hunt SA, Applegate E (2012). Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and Administrative Procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 571. ISBN 9781455701506. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Ngan Kee WD (April 1998). "Intrathecal pethidine: pharmacology and clinical applications". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 26 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1177/0310057X9802600202. PMID 9564390.

- ^ Ngan Kee WD (June 1998). "Epidural pethidine: pharmacology and clinical experience". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 26 (3): 247–255. doi:10.1177/0310057X9802600303. PMID 9619217.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Demerol, Pethidine (meperidine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Shipton E (March 2006). "Should New Zealand continue signing up to the Pethidine Protocol?" (PDF). The New Zealand Medical Journal. 119 (1230): U1875. PMID 16532042. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-08.

- ^ a b c d Latta KS, Ginsberg B, Barkin RL (January–February 2002). "Meperidine: a critical review". American Journal of Therapeutics. 9 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1097/00045391-200201000-00010. PMID 11782820. S2CID 23410891.

- ^ a b MacPherson RD, Duguid MD (2008). "Strategy to Eliminate Pethidine Use in Hospitals". Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 38 (2): 88–89. doi:10.1002/j.2055-2335.2008.tb00807.x. S2CID 71812645.

- ^ Mather LE, Meffin PJ (September–October 1978). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of pethidine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 3 (5): 352–368. doi:10.2165/00003088-197803050-00002. PMID 359212. S2CID 35402662.

- ^ a b Rossi S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ US 2167351 Piperidine compounds and a process of preparing them

- ^ Michaelis M, Schölkens B, Rudolphi K (April 2007). "An anthology from Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 375 (2): 81–84. doi:10.1007/s00210-007-0136-z. PMID 17310263. S2CID 27774155.

- ^ Reynolds AK, Randall LO (1957). Morphine and Allied Drugs. Toronto/London: University of Toronto Press/Oxford University Press. pp. 273–319.

- ^ Kaiko RF, Foley KM, Grabinski PY, Heidrich G, Rogers AG, Inturrisi CE, Reidenberg MM (February 1983). "Central nervous system excitatory effects of meperidine in cancer patients". Annals of Neurology. 13 (2): 180–185. doi:10.1002/ana.410130213. PMID 6187275. S2CID 44353966.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 52X. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ "Parenteral opioids for labor pain relief: A systematic review - American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology". www.ajog.org. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ "WHO | Parenteral opioids for maternal pain relief in labour". apps.who.int. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Pain relief in labour - Pregnancy and baby guide - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-06-12. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ Blueprints - Family Medicine (3rd edition)

- ^ Logan A, Sangkachand P, Funk M (December 2011). "Optimal management of shivering during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest". Critical Care Nurse. 31 (6): e18–30. doi:10.4037/ccn2011618. PMID 22135340.

- ^ "Essential Medicines WHO Model List (revised April 2002)" (PDF). apps.who.int (12th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. April 2002. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ "Essential Medicines WHO Model List (revised April 2003)" (PDF). apps.who.int (13th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. April 2003. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 911–914.

- ^ "Package insert for meperidine hydrochloride" (PDF). Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim. 2005.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 911–914.

- ^ "Package insert for meperidine hydrochloride" (PDF). Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim. 2005.

- ^ Brody J (February 27, 2007). "A Mix of Medicines That Can Be Lethal". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ^ "Serious Reactions with Tramadol: Seizures and Serotonin Syndrome". medsafe.govt.nz (Prescriber Update 28(1) ed.). New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre, Dunedin: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. October 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Bryant B, Knights K (2010). Pharmacology for Health Professionals (3rd ed.). Chatswood: Mosby Australia. ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

- ^ Koczmara C, Perri D, Hyland S, Rousseaux L (2005). "Meperidine (Demerol) safety issues" (PDF). Dynamics. 16 (1): 8–12. PMID 15835452. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ^ Laurence B (2010). Goodman & Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 549. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- ^ "Petidin Meda - FASS Vårdpersonal".

- ^ Wagner LE, Eaton M, Sabnis SS, Gingrich KJ (November 1999). "Meperidine and lidocaine block of recombinant voltage-dependent Na+ channels: evidence that meperidine is a local anesthetic". Anesthesiology. 91 (5): 1481–1490. doi:10.1097/00000542-199911000-00042. PMID 10551601. S2CID 34806974.

- ^ a b c d Izenwasser S, Newman AH, Cox BM, Katz JL (February 1996). "The cocaine-like behavioral effects of meperidine are mediated by activity at the dopamine transporter". European Journal of Pharmacology. 297 (1–2): 9–17. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(95)00696-6. PMID 8851160.

- ^ Lomenzo SA, Rhoden JB, Izenwasser S, Wade D, Kopajtic T, Katz JL, Trudell ML (March 2005). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of meperidine analogues at monoamine transporters". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (5): 1336–1343. doi:10.1021/jm0401614. PMID 15743177.

- ^ a b c d "Demerol: Is It the Best Analgesic?" (PDF), Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting Service Patient Safety Advisory, 3 (2), June 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-20, retrieved 2013-04-15

- ^ Davis S (August 2004). "Use of pethidine for pain management in the emergency department: a position statement of the NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group" (PDF). New South Wales Therapeutic Advisory Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-09. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b c Latta KS, Ginsberg B, Barkin RL (January–February 2002). "Meperidine: a critical review". American Journal of Therapeutics. 9 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1097/00045391-200201000-00010. PMID 11782820. S2CID 23410891.

- ^ Molloy A (2002). "Does pethidine still have a place in therapy?". Australian Prescriber. 25 (1): 12–13. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2002.008.

- ^ Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL (August 2004). "A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997-2002". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 28 (2): 176–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.387.1900. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. PMID 15276196.

- ^ Joranson DE, Gilson AM (October 2005). "Drug crime is a source of abused pain medications in the United States". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 30 (4): 299–301. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.001. PMID 16256890.

- ^ "WHO | Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the World Health Organization". WHO. Archived from the original on July 4, 2004.

- ^ a b Babor T, Campbell R, Room R, Saunders J, eds. (1994). Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154468-9.

- ^ Patent Appl. DE 679 281 IG Farben 1937.

- ^ "Final Adjusted Aggregate Production Quotas for Schedule I and II Controlled Substances and Assessment of Annual Needs for the List I Chemicals Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine for 2014". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ^ "Harold Shipman: Timeline". BBC News. 18 July 2002. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Bunyan N (16 June 2001). "The Killing Fields of Harold Shipman". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Grady C (2021-01-29). "This notorious poet is required reading in Denmark. Her masterpiece is now out in the US". Vox. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ Jackson M (1997). Blood on the Dance Floor: HIStory in the Mix (booklet). Epic Records, Sony Music, MJJ.

- ^ James SD (26 June 2009). "Friend Says Michael Jackson Battled Demerol Addiction". ABC News.

- ^ "What is pethidine – and why is Call the Midwife's Dr McNulty so desperate for a dose?". Radio Times. 23 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Gibson W (1984). Neuromancer. Ace. p. 105. ISBN 0-441-56956-0.

- Analgesics

- Convulsants

- Ethyl esters

- Euphoriants

- Glycine receptor antagonists

- Kappa-opioid receptor agonists

- Local anesthetics

- Mu-opioid receptor agonists

- Muscarinic antagonists

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- 4-Phenylpiperidines

- Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Sodium channel blockers

- Synthetic opioids

- German inventions of the Nazi period

- 1938 in science

- 1938 in Germany