Mahathir Mohamad

Mahathir Mohamad | |

|---|---|

| محاضر بن محمد | |

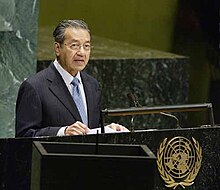

Mahathir in 2019 | |

| 4th and 7th Prime Minister of Malaysia | |

| In office 10 May 2018 – 1 March 2020 Interim: 24 February 2020 – 1 March 2020 | |

| Monarchs | Muhammad V Abdullah |

| Deputy | Wan Azizah Wan Ismail |

| Preceded by | Najib Razak |

| Succeeded by | Muhyiddin Yassin |

| Constituency | Langkawi |

| In office 16 July 1981 – 31 October 2003 | |

| Monarchs | Ahmad Shah Iskandar Azlan Shah Ja'afar Salahuddin Sirajuddin |

| Deputy | Musa Hitam (1981–1986) Ghafar Baba (1986–1993) Anwar Ibrahim (1993–1998) Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (1999–2003) |

| Preceded by | Hussein Onn |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| Minister of Education | |

| Covering duties 3 January 2020 – 24 February 2020 Acting Minister | |

| Monarch | Abdullah |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Deputy | Teo Nie Ching |

| Preceded by | Maszlee Malik |

| Succeeded by | Mohd Radzi Md Jidin (Education) Noraini Ahmad (Higher Education) |

| Constituency | Langkawi |

| In office 5 September 1974 – 1 January 1978 | |

| Monarchs | Abdul Halim Yahya Petra |

| Prime Minister | Abdul Razak Hussein Hussein Onn |

| Deputy | Chan Siang Sun |

| Preceded by | Mohamed Yaacob |

| Succeeded by | Musa Hitam |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 5 June 2001 – 31 October 2003 | |

| Monarchs | Salahuddin Sirajuddin |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Deputy | Shafie Salleh Chan Kong Choy (2001–2003) Ng Yen Yen (2003) |

| Preceded by | Daim Zainuddin |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| In office 7 September 1998 – 7 January 1999 Serving with Mustapa Mohamed | |

| Monarch | Ja'afar |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Deputy | Mohamed Nazri Abdul Aziz Wong See Wah |

| Preceded by | Anwar Ibrahim |

| Succeeded by | Daim Zainuddin |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 8 May 1986 – 8 January 1999 | |

| Monarchs | Iskandar Azlan Shah Ja'afar |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Deputy | Megat Junid Megat Ayub (1986–1997) Ong Ka Ting (1995–1999) Azmi Khalid (1997–1999) |

| Preceded by | Musa Hitam |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 17 July 1981 – 6 May 1986 | |

| Monarchs | Ahmad Shah Iskandar |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Deputy | Abang Abu Bakar Abang Mustapha |

| Preceded by | Hussein Onn |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| 4th Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia | |

| In office 5 March 1976 – 16 July 1981 | |

| Monarchs | Yahya Petra Ahmad Shah |

| Prime Minister | Hussein Onn |

| Preceded by | Hussein Onn |

| Succeeded by | Musa Hitam |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| Minister of Trade and Industry | |

| In office 1 January 1978 – 16 July 1981 | |

| Monarchs | Yahya Petra Ahmad Shah |

| Prime Minister | Hussein Onn |

| Deputy | Abdul Manan Othman (1978) Lew Sip Hon (1978–1981) |

| Preceded by | Hamzah Abu Samah |

| Succeeded by | Ahmad Rithaudden Tengku Ismail |

| Constituency | Kubang Pasu |

| 1st Chairman of the Malaysian United Indigenous Party | |

| Assumed office 7 September 2016 | |

| President | Muhyiddin Yassin |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Constituency | Langkawi |

| 5th President of the United Malays National Organisation | |

| In office 28 June 1981 – 31 October 2003 | |

| Deputy | Musa Hitam (1981-1987) Ghafar Baba (1987-1993) Anwar Ibrahim (1993-1998) Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (1999-2003) |

| Preceded by | Hussein Onn |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Member of the Malaysian Parliament for Langkawi | |

| Assumed office 9 May 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Nawawi Ahmad (UMNO–BN) |

| Majority | 8,893 (2018) |

| Member of the Malaysian Parliament for Kubang Pasu | |

| In office 24 August 1974 – 21 March 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency Established |

| Succeeded by | Mohd Johari Baharum (UMNO–BN) |

| Majority | Unopposed (1974) 8,245 (1978) 15,761 (1982) 15,298 (1986) 22,062 (1990) 17,226 (1995) 10,138 (1999) |

| Member of the Dewan Negara for Kedah | |

| In office 30 December 1972 – 23 August 1974 | |

| Monarch | Abdul Halim |

| Prime Minister | Abdul Razak Hussein |

| Preceded by | Md Hanipah Sheikh Alauddin (UMNO–Perikatan) |

| Succeeded by | Ali Ismail (UMNO–BN) |

| Member of the Malaysian Parliament for Kota Setar Selatan | |

| In office 25 April 1964 – 10 May 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Wan Sulaiman Wan Tam (UMNO–Perikatan) |

| Succeeded by | Yusof Rawa (PMIP) |

| Majority | 4,210 (1964) |

| In office 28 June 1981 – 31 October 2003 | |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mahathir bin Mohamad 10 July 1925 Alor Setar, Kedah, British Malaya (now Malaysia) |

| Political party | UMNO (1946–1969, 1972–2008, 2009–2016) BERSATU (2016-2020) Independent (28 May 2020) |

| Other political affiliations | Barisan Nasional Pakatan Harapan |

| Spouse | Siti Hasmah Mohamad Ali |

| Children | 7 (including Marina, Mokhzani and Mukhriz) |

| Relatives | Ismail Mohd Ali (brother-in-law) |

| Alma mater | King Edward VII College of Medicine |

| Awards | Awards and recognitions |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

| Mahathir Mohamad on Parliament of Malaysia | |

Template:Mahathir Mohamad series

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Malaysia |

|---|

|

Template:Mahathir Mohamad timeline

Mahathir bin Mohamad (Jawi: محاضر بن محمد, IPA: [maˈhaðɪr bɪn moˈhamad]; born 10 July 1925) is a Malaysian politician who served as the prime minister of Malaysia from 1981 to 2003 and 2018 to 2020. He is a member of the Parliament of Malaysia for the Langkawi constituency in the state of Kedah. Mahathir's political career has spanned more than 70 years starting with his participation in protests against non-Malays gaining Malaysian citizenship during the Malayan Union through to forming his own party, the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (PPBM), in 2016.

Born and raised in Alor Setar, Kedah, Mahathir excelled at school and became a physician. He became active in the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) before entering parliament in 1964. He served one term before losing his seat, subsequently falling out with Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman and being expelled from UMNO. When Abdul Rahman resigned, Mahathir re-entered UMNO and parliament, and was promoted to the Cabinet. By 1977, he had risen to deputy prime minister. In 1981, he was sworn in as prime minister after the resignation of his predecessor, Hussein Onn.

During Mahathir's first tenure as prime minister, Malaysia experienced a period of rapid modernization and economic growth, and his government initiated a series of bold infrastructure projects. Mahathir was a dominant political figure, winning five consecutive general elections and fending off a series of rivals for the leadership of UMNO. However, his accumulation of power came at the expense of the independence of the judiciary and the traditional powers and privileges of Malaysia's royalty. He used the controversial Internal Security Act to detain activists, non-mainstream religious figures, and political opponents, including the deputy prime minister whom he fired in 1998, Anwar Ibrahim. Mahathir's record of curbing civil liberties and his antagonism towards western interests and economic policy made his relationships with western nations difficult. As prime minister, he was an advocate of third-world development and a prominent international activist.

After leaving office, Mahathir became a strident critic of his hand-picked successor Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and later Najib Razak. In 2016, Mahathir quit UMNO in light of its support for the actions of Prime Minister Najib, in spite of the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal. Later that year, the Malaysian United Indigenous Party was officially registered as a political party, with Mahathir as chairman. In 2018, Mahathir was announced as the Pakatan Harapan coalition candidate for prime minister for the 2018 general election, in a plan to pardon Anwar Ibrahim and hand a role to him if the campaign was successful. Following a decisive victory for Pakatan Harapan in the 2018 election, Mahathir was sworn in as prime minister. He was the first prime minister not to represent the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition (or its predecessor, the Alliance Party) and also the first to serve from two different parties and on non-consecutive terms. At the time of his resignation in 2020, he was the oldest currently-serving state leader.

Early life and family

Mahathir was born at his parents' home in a poor neighbourhood at Lorong Kilang Ais, Alor Setar, the capital of the Malay sultanate of Kedah, which was then a British protectorate, on 10 July 1925.[1][N 1] His mother, Wan Tempawan, was a Malay of Kedah. His father, Mohamad Iskandar, was a Penang Malay of partly Indian ancestry. Mahathir's paternal grandfather had come from Kerala and married a Malay woman.[2] Mahathir's partly non-Malay ancestry, which he largely kept quiet during his political career, is a feature shared by Malaysia's six prime ministers. But another aspect of Mahathir's birth set him apart from the other five: he was not born into the aristocracy or a prominent religious or political family.[3][N 2] Mohamad was the principal of an English-medium secondary school, whose lower middle-class status meant his daughters were unable to enrol in secondary school; while Wan Tempawan had only distant relations to members of Kedah's royalty. Both had been married previously; Mahathir was born with six half-siblings and two full-siblings.[4] Currently his house was converted as Mahathir Mohamad birth house complex and opened to public.[6]

Mahathir was a hard-working school student. Discipline imposed by his father motivated him to study, and he showed little interest in sports. He won a position in a selective English medium secondary school, having become fluent in English well ahead of his primary school peers.[7] With schools closed during the Japanese occupation of Malaya in World War II, he went into small business, first selling coffee and later pisang goreng (banana fritters) and other snacks.[1] After the war, he graduated from secondary school with high marks and enrolled to study medicine at the King Edward VII College of Medicine in Singapore.[8] In college he met his future wife, Siti Hasmah Mohamad Ali, a fellow medical student. After graduating with an MBBS medical degree, Mahathir worked as a physician in government service before marrying Siti Hasmah in 1956 and returning to Alor Setar the following year to set up his own practice. He was the town's first Malay physician, and a successful one. He built a large house, invested in various businesses, and employed a Chinese man to chauffeur him in his Pontiac Catalina (most chauffeurs at the time were Malay).[9][10] He and Siti Hasmah had their first child, Marina, in 1957, before conceiving three others and adopting three more over the following 28 years.[11]

Early political career

Mahathir had been politically active since the end of the Japanese occupation of Malaya, when he joined protests against the granting of citizenship to non-Malays under the short-lived Malayan Union.[12] He later argued for affirmative action for Malays at medical college. While at college he contributed to The Straits Times under the pseudonym "C.H.E. Det", and a student journal, in which he fiercely promoted Malay rights, such as restoring Malay as an official language.[13] While practising as a physician in Alor Setar, Mahathir became active in UMNO; by the time of the first general election for the independent state of Malaya in 1959, he was the chairman of the party in Kedah.[14] Despite his prominence in UMNO, Mahathir was not a candidate in the 1959 election, ruling himself out following a disagreement with then Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman. The relationship between the two Kedahans had been strained since Mahathir had criticised Abdul Rahman's agreement to the retention of British and Commonwealth forces in Malaya after independence. Now Abdul Rahman opposed Mahathir's plans to introduce minimum educational qualifications for UMNO candidates. For Mahathir this was a significant enough slight to delay his entry into national politics in protest. The delay did not last for long. In the following general election in 1964, he was elected as the federal parliamentarian for the Alor Setar-based seat of Kota Setar Selatan.[15]

Elected to parliament in a volatile political period, Mahathir, as a government backbencher, launched himself into the main conflict of the day: the future of Singapore, with its large and economically powerful ethnic Chinese population, as a state of Malaysia. He vociferously attacked Singapore's dominant People's Action Party for being "pro-Chinese" and "anti-Malay" and called its leader, Lee Kuan Yew, "arrogant". Singapore was expelled from Malaysia in Mahathir's first full year in parliament.[15][16] However, despite Mahathir's prominence as a backbencher, he lost his seat in the 1969 election, defeated by Yusof Rawa of the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).[17] Mahathir attributed the loss of his seat to ethnic Chinese voters switching support from UMNO to PAS (being a Malay-dominated seat, only the two major Malay parties fielded candidates, leaving Chinese voters to choose between the Malay-centric UMNO and the Islamist PAS).[18]

Large government losses in the election were followed by the race riots of 13 May 1969, in which hundreds of people were killed in clashes between Malays and Chinese. The previous year, Mahathir had predicted the outbreak of racial hostility. Now, outside parliament, he openly criticised the government, sending a letter to Abdul Rahman in which the prime minister was criticised for failing to uphold Malay interests. The letter, which soon became public, called for Abdul Rahman's resignation.[19] By the end of the year, Mahathir had been fired from UMNO's Supreme Council and expelled from the party; Abdul Rahman had to be persuaded not to have him arrested.[17][18]

While in the political wilderness, Mahathir wrote his first book, The Malay Dilemma, in which he set out his vision for the Malay community. The book argued that a balance had to be achieved between enough government support for Malays so that their economic interests would not be dominated by the Chinese, and exposing Malays to sufficient competition to ensure that over time, Malays would lose what Mahathir saw as the characteristics of avoiding hard work and failing to "appreciate the real value of money and property".[20] The book continued Mahathir's criticism of Abdul Rahman's government, and it was promptly banned. The ban was only lifted after Mahathir became prime minister in 1981; he thus served as a minister and deputy prime minister while being the author of a banned book.[17][21] Academics R. S. Milne and Diane K. Mauzy argue that Mahathir's relentless attacks were the principal cause of Abdul Rahman's downfall and subsequent resignation as prime minister in 1970.[22]

Minister of Education

Abdul Rahman resigned in 1970 and was replaced by Abdul Razak Hussein. Razak encouraged Mahathir back into the party, and had him appointed as a Senator in 1973.[23] He rose quickly in the Razak government, returning to UMNO's Supreme Council in 1973, and being appointed to Cabinet in 1974 as the Minister for Education. He also returned to the House of Representatives, winning the Kedah-based seat of Kubang Pasu unopposed in the 1974 election.[17] One of his first acts as Minister for Education was to introduce greater government control over Malaysia's universities, despite strong opposition from the academic community.[24] He also moved to limit politics on university campuses, giving his ministry the power to discipline students and academics who were politically active, and making scholarships for students conditional on the avoidance of politics.[25]

In 1975, Mahathir ran for one of the three vice-presidencies of UMNO. The contest was considered to be a battle for the succession of the party's leadership, with both Razak and his deputy, Hussein Onn, in declining health. Each of Razak's preferred candidates was elected: former Chief Minister of Melaka, Ghafar Baba; Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, a wealthy businessman and member of Kelantan's royal family; and Mahathir. When Razak died the following year, Hussein as his successor was forced to choose between the three men to be deputy prime minister; he also considered the ambitious minister Ghazali Shafie. Each of Mahathir's rivals had significant political liabilities: Ghazali, having been defeated by the others for a vice-presidency, lacked the support of UMNO members; Ghafar had no higher education and was not fluent in English; and Razaleigh was young, inexperienced and, critically, unmarried. But Hussein's decision was not easy. Hussein and Mahathir were not close allies, and Hussein knew the choice of Mahathir would displease Abdul Rahman, still alive and revered as the father of Malaysia's independence. After six weeks of indecision Mahathir was, much to his surprise, appointed as Hussein's deputy. The appointment meant that Mahathir was the anointed successor to the prime ministership.[26][27]

However, Mahathir was not an influential deputy prime minister. Hussein was a cautious leader who rejected many of Mahathir's bold policy proposals. While the relationship between Hussein and Mahathir was distant, Ghazali and Razaleigh became Hussein's closest advisers, often bypassing the more senior Mahathir when accessing Hussein. Nonetheless, when Hussein relinquished power due to ill health in 1981, Mahathir succeeded him unopposed and with his blessing.[28]

First term as prime minister

Domestic affairs

Mahathir was sworn in as prime minister on 16 July 1981, at the age of 56.[29] One of his first acts was to release 21 detainees held under the Internal Security Act, including journalist Samad Ismail and a former deputy minister in Hussein's government, Abdullah Ahmad, who had been suspected of being an underground communist.[30] He appointed his close ally, Musa Hitam, as deputy prime minister.[31]

Early years (1981–1987)

Mahathir exercised caution in his first two years in power, consolidating his leadership of UMNO and, with victory in the 1982 general election, the government.[32][33] In 1983, Mahathir commenced the first of a number of battles he would have with Malaysia's royalty during his premiership. The position of Yang di-Pertuan Agong, the Malaysian head of state, was due to rotate in to either the elderly Idris Shah II of Perak or the controversial Iskandar of Johor, who had only a few years earlier been convicted of manslaughter. Thus Mahathir had grave reservations about the two Sultans, who were both activist rulers of their own states.[34][35] Mahathir tried to pre-emptively limit the power that the new Agong could wield over his government, introducing to parliament amendments to the Constitution to deem the Agong to assent to any bill that had not been assented within 15 days of passage by Parliament. The proposal would also remove the power to declare a state of emergency from the Agong and place it with the prime minister. The Agong at the time, Ahmad Shah of Pahang, agreed with the proposals in principle but balked when he realised that the proposal would also deem Sultans to assent to laws passed by state assemblies. Supported by the Sultans, the Agong refused to assent to the constitutional amendments, which had by then passed both houses of Parliament with comfortable majorities.[36][37] When the public became aware of the impasse, and the Sultans refused to compromise with the government, Mahathir took to the streets to demonstrate public support for his position in mass rallies. The press took the side of the government, although a large minority of Malays, including conservative UMNO politicians, and an even larger proportion of the Chinese community supported the Sultans. After five months, the crisis resolved, as Mahathir and the Sultans agreed to a compromise. The Agong would retain the power to declare a state of emergency, but if he refused to assent to a bill, the bill would be returned to Parliament, which could then override the Agong's veto.[38]

On the economic front, Mahathir inherited the New Economic Policy from his predecessors, which was designed to improve the economic position of the bumiputera (Malaysia's Malays and indigenous peoples) through targets and affirmative action in areas such as corporate ownership and university admission.[39] Mahathir also actively pursued privatisation of government enterprises from the early 1980s, both for the liberal economic reasons it was being pursued by contemporaries such as Margaret Thatcher, and because he felt that combined with affirmative action for the bumiputera it could provide economic opportunities for bumiputera businesses.[40] His government privatised airlines, utilities and telecommunication firms, accelerating to a rate of about 50 privatisations a year by the mid-1990s.[41] While privatisation generally improved the working conditions of Malaysians in privatised industries and raised significant revenue for the government, many privatisations occurred in the absence of open tendering processes and benefited Malays who supported UMNO. One of the most notable infrastructure projects at the time was the construction of the North–South Expressway, a motorway running from the Thai border to Singapore; the contract to construct the expressway was awarded to a business venture of UMNO.[42] Mahathir also oversaw the establishment of the car manufacturer Proton as a joint venture between the Malaysian government and Mitsubishi. By the end of the 1980s, Proton had overcome poor demand and losses to become, with the support of protective tariffs, the largest car maker in Southeast Asia and a profitable enterprise.[43]

In Mahathir's early years as prime minister, Malaysia was experiencing a resurgence of Islam among Malays. Malays were becoming more religious and more conservative. PAS, which had in the 1970s joined UMNO in government, responded to the resurgence by taking an increasingly strident Islamist stand under the leadership of the man who in 1969 had defeated Mahathir for his parliamentary seat, Yusof Rawa. Mahathir tried to appeal to religious voters by establishing Islamic institutions such as the International Islamic University of Malaysia which could promote Islamic education under the government's oversight. He also attracted Anwar Ibrahim, the leader of the Malaysian Islamic Youth Movement (ABIM) to join UMNO. In some cases, Mahathir's government employed repression against more extreme exponents of Islamism. Ibrahim Libya, a popular Islamist leader, was killed in a police shoot-out in 1985; Al-Arqam, a religious sect, was banned and its leader, Ashaari Mohammad, arrested under the Internal Security Act.[44] Mahathir comprehensively defeated PAS at the polls in 1986, winning 83 seats of the 84 seats it contested, leaving PAS with just one MP.[45]

Exerting power (1987–1990)

Any illusion that the 1986 election may have created about Mahathir's political dominance was short-lived. In 1987, he was challenged for the presidency of UMNO, and effectively the prime ministership, by Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah. Razaleigh's career had gone backwards under Mahathir, being demoted from the Ministry of Finance to the Ministry of Trade and Industry. Razaleigh was supported by Musa, who had resigned as deputy prime minister the previous year. While Musa and Mahathir were originally close allies, the two had fallen out during Mahathir's premiership, with Musa claiming that Mahathir no longer trusted him. Razaleigh and Musa ran for the UMNO presidency and deputy presidency on a joint ticket against Mahathir and his new choice for deputy, Ghafar Baba. The tickets were known as Team B and Team A respectively. Mahathir's Team A enjoyed the support of the press, most party heavyweights, and even Iskandar, now the Agong, although some significant figures such as Abdullah Badawi supported Team B. In the election, held on 24 April 1987, Team A prevailed. Mahathir was re-elected a by a narrow margin, receiving the votes of 761 party delegates to Razaleigh's 718. Ghafar defeated Musa by a slightly larger margin. Mahathir responded by purging seven Team B supporters from his ministry, while Team B refused to accept defeat and initiated litigation. In an unexpected decision in February 1988, the High Courts ruled that UMNO was an illegal organisation as some of its branches had not been lawfully registered.[46][47]

Each faction raced to register a new party under the UMNO name. Mahathir's side successfully registered the name "UMNO Baru" ("new UMNO"), while Team B's application to register "UMNO Malaysia" was rejected. UMNO Malaysia, under the leadership of Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah and with the support of both of Malaysia's surviving former prime ministers, Abdul Rahman and Hussein, registered the party Semangat 46 instead.[48] The Lord President of the Supreme Court, Salleh Abas, sent a letter of protest to the Agong. Mahathir then suspended Salleh for "gross misbehaviour and conduct", ostensibly because the letter was a breach of protocol. A tribunal set up by Mahathir found Salleh guilty and recommended to the Agong that Salleh be dismissed. Five other judges of the court supported Salleh, and were suspended by Mahathir. A newly constituted court dismissed Team B's appeal, allowing Mahathir's faction to continue to use the name UMNO. According to Milne and Mauzy, the episode destroyed the independence of Malaysia's judiciary.[49]

At the same time as the political and judicial crises, Mahathir initiated a crackdown on opposition dissidents with the use of the Internal Security Act. Mahathir later declared that it was only used to lock up people accused of riots, unlawful assembly, terrorism and those who have murdered police officers. The appointment of a number of administrators who did not speak Mandarin to Chinese schools provoked an outcry among Chinese Malaysians to the point where UMNO's coalition partners the Malaysian Chinese Association and Gerakan joined the Democratic Action Party (DAP) in protesting the appointments. UMNO's Youth wing held a provocative protest that triggered a shooting by a lone Malay gunman, and only Mahathir's interference prevented UMNO from staging a larger protest. Instead, Mahathir ordered what Wain calls "the biggest crackdown on political dissent Malaysia had ever seen". Under the police operation codenamed "Operation Lalang", 119 people were arrested and detained without charge under the Internal Security Act. Mahathir argued that the detentions were necessary to prevent a repeat of the 1969 race riots. Most of the detainees were prominent opposition activists, including the leader of the DAP, Lim Kit Siang, and nine of his fellow MPs. Three newspapers sympathetic to the opposition were shut down.[50] Mahathir suffered a heart attack in early 1989,[51] but recovered to lead Barisan Nasional to victory in the 1990 election. Semangat 46 failed to make any headway outside Razaleigh's home state of Kelantan.[52]

Economic development to financial crisis (1990–1998)

The expiry of the Malaysian New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1990 gave Mahathir the opportunity to outline his economic vision for Malaysia. In 1991, he announced Vision 2020, under which Malaysia would aim to become a fully developed country within 30 years.[53] The target would require average economic growth of approximately seven per cent of gross domestic product per annum.[54] One of Vision 2020's features would be to gradually break down ethnic barriers. Vision 2020 was accompanied by the NEP's replacement, the National Development Policy (NDP), under which some government programs designed to benefit the bumiputera exclusively were opened up to other ethnicities.[55] The NDP achieved success out one of its main aims, poverty reduction. By 1995, less than nine per cent of Malaysians lived in poverty and income inequality had narrowed.[56] Mahathir's government cut corporate taxes and liberalised financial regulations to attract foreign investment. The economy grew by over nine per cent per annum until 1997 prompting other developing countries to try to emulate Mahathir's policies.[57] Much of the credit for Malaysia's economic development in the 1990s went to Anwar Ibrahim, appointed by Mahathir as finance minister in 1991.[58] The government rode the economic wave and won the 1995 election with an increased majority.[59]

Mahathir initiated a series of major infrastructure projects in the 1990s. One of the largest was the Multimedia Super Corridor, an area south of Kuala Lumpur, in the mould of Silicon Valley, designed to cater for the information technology industry. However, the project failed to generate the investment anticipated. Other Mahathir projects included the development of Putrajaya as the home of Malaysia's public service, and bringing a Formula One Grand Prix to Sepang. One of the most controversial developments was the Bakun Dam in Sarawak. The ambitious hydro-electric project was intended to carry electricity across the South China Sea to satisfy electricity demand in peninsular Malaysia. Work on the dam was eventually suspended due to the Asian financial crisis.[60]

In 1997, the Asian financial crisis which began in Thailand in mid 1997 threatened to devastate Malaysia. The value of the ringgit plummeted due to currency speculation, foreign investment fled, and the main stock exchange index fell by over 75 per cent. At the urging of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the government cut government spending and raised interest rates, which only served to exacerbate the economic situation. In 1998, in a controversial approach Mahathir reversed this policy course in defiance of the IMF and his own deputy, Anwar. He increased government spending and fixed the ringgit to the US dollar. The result confounded his international critics and the IMF. Malaysia recovered from the crisis faster than its Southeast Asian neighbours. In the domestic sphere, it was a political triumph. Amidst the economic events of 1998, Mahathir had dismissed Anwar as finance minister and deputy prime minister, and he could now claim to have rescued the economy in spite of Anwar's policies.[61]

In his second decade in office, Mahathir had again found himself battling Malaysia's royalty. In 1992, Sultan Iskandar's son, a representative field hockey player, was suspended from competition for five years for assaulting an opponent. Iskandar retaliated by pulling all Johor hockey teams out of national competitions. When his decision was criticised by a local coach, Iskandar ordered him to his palace and beat him. The federal parliament unanimously censured Iskandar, and Mahathir leapt at the opportunity to remove the constitutional immunity of the sultans from civil and criminal suits. The press backed Mahathir and, in an unprecedented development, started airing allegations of misconduct by members of Malaysia's royal families. As the press revealed examples of the rulers' extravagant wealth, Mahathir resolved to cut financial support to royal households. With the press and the government pitted against them, the sultans capitulated to the government's proposals. Their powers to deny assent to bills were limited by further constitutional amendments passed in 1994. With the status and powers of the Malaysian royalty diminished, Wain writes that by the mid-1990s Mahathir had become the country's "uncrowned king".[62]

The final years and succession (1998–2003)

By the mid-1990s it had become clear that the most serious threat to Mahathir's power was the leadership ambition of his deputy, Anwar. Anwar began to distance himself from Mahathir, overtly promoting his superior religious credentials and appearing to suggest he favoured loosening the restrictions on civil liberties that had become a hallmark of Mahathir's premiership.[63] However, Mahathir continued to back Anwar as his successor until their relationship collapsed dramatically during the Asian financial crisis. Their positions gradually diverged, with Mahathir abandoning the tight monetary and fiscal policies urged by the IMF. At the UMNO General Assembly in 1998, a leading Anwar supporter, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, criticised the government for not doing enough to combat corruption and cronyism. As Mahathir took the reins of Malaysia's economic policy over the coming months, Anwar was increasingly sidelined. On 2 September, he was dismissed as deputy prime minister and finance minister, and promptly expelled from UMNO. No immediate reasons were given for the dismissal, although the media speculated that it related to lurid allegations of sexual misconduct circulated in a "poison pen letter" at the general assembly.[64] As more allegations surfaced, large public rallies were held in support of Anwar. On 20 September, he was arrested and placed in detention under the Internal Security Act.[65]

Anwar stood trial on four charges of corruption, arising from allegations that Anwar abused his power by ordering police to intimidate persons who had alleged Anwar had sodomised them. Before Anwar's trial, Mahathir told the press that he was convinced of Anwar's guilt. He was found guilty in April 1999 and sentenced to six years in prison. In another trial shortly after, Anwar was sentenced to another nine years in prison on a conviction for sodomy. The sodomy conviction was overturned on appeal after Mahathir left office.[66]

While Mahathir had vanquished his rival, it came at a cost to his standing in the international community and domestic politics. US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright defended Anwar as a "highly respectable leader" who was "entitled to due process and a fair trial".[67] In a speech in Kuala Lumpur, which Mahathir attended, US Vice-President Al Gore stated that "we continue to hear calls for democracy", including "among the brave people of Malaysia".[68] At the APEC summit in 1999, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien refused to meet Mahathir, while his foreign minister met with Anwar's wife, Wan Azizah Wan Ismail.[69] Wan Azizah had formed a liberal opposition party, the National Justice Party (Keadilan) to fight the 1999 election. UMNO lost 18 seats and two state governments as large numbers of Malay voters flocked to PAS and Keadilan, many in protest at the treatment of Anwar.[70]

In September 2001 debate was caused by Mahathir's announcement that Malaysia was already an Islamic state.[71] At UMNO's general assembly in 2002, he announced that he would resign as prime minister, only for supporters to rush to the stage and convince him tearfully to remain. He subsequently fixed his retirement for October 2003, giving him time to ensure an orderly and uncontroversial transition to his anointed successor, Abdullah Badawi.[72] In a speech made before the Organization of the Islamic Conference shortly before he left office, Mahathir claimed "the Jews rule the world by proxy: They get others to fight and die for them."[73] His speech was denounced by President George W. Bush.[74] Having spent over 22 years in office, Mahathir was the world's longest-serving elected leader when he retired.[75]

Foreign relations

During Mahathir's term, Malaysia's relationship with the West was generally fine despite his being known as an outspoken critic towards it.[76] Early during his tenure, a small disagreement with the United Kingdom over university tuition fees sparked a boycott of all British goods led by Mahathir, in what became known as the "Buy British Last" campaign. It also led to a search for development models in Asia, most notably Japan. This was the beginning of his famous "Look East Policy".[77] Although the dispute was later resolved by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Mahathir continued to emphasise Asian development models over contemporary Western ones. He particularly criticised the double standards of Western nations.[78]

United States

Mahathir has been publicly critical of the Foreign Policy of the United States from time to time, particularly during the George W. Bush presidency.[79] and yet relations between the two countries were still positive and the United States was the biggest source of foreign investment, and was Malaysia's biggest customer during Mahathir's rule. Furthermore, Malaysian military officers continued to train in the US under the International Military Education And Training (IMET) program. The BBC reported that relations with the United States took a turn for the worse in 1998 when Al Gore, Vice President of the United States, gave a speech at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) conference hosted by Malaysia.[80] Gore stated that:

Democracy confers a stamp of legitimacy that reforms must have in order to be effective. And so, among nations suffering economic crises, we continue to hear calls for democracy, calls for reform, in many languages – People Power, doi moi, reformasi. We hear them today – right here, right now – among the brave people of Malaysia.[81]

Gore and the United States were critical of the trial of Mahathir's former deputy Anwar Ibrahim, going so far as to label it as a "show trial". US News and World Report called the trial a "tawdry spectacle."[82] Also, Anwar was the preeminent Malaysian spokesperson for the economic policies preferred by the IMF, which included interest-rate hikes. An article in Malaysia Today commented that "Gore's comments constituted a none-too-subtle attack on Malaysia's Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and more generally on governments, including Japan, that resist US demands for further market reforms."[83]

During the ASEAN meeting in 1997, Mahathir made a speech condemning the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, suggesting its revision. He said that in Asia, the society's interests are more important than an individual's interests. He added that Asians need economic growth more than civil liberties. These remarks did not endear him to US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who was a guest at the meeting[84] and paid a visit to Anwar's wife following his firing and subsequent imprisonment.[85]

The United States government has previously criticised the Malaysian government for implementing the ISA, and Mahathir has not hesitated to point to the United States for justification of his own actions. In speaking of arbitrary detention without trial of prisoners of conscience in Malaysia, he said: "Events in the United States have shown that there are instances where certain special powers need to be used in order to protect the public for the general good."[86] In 2003 Mahathir spoke to the Non-Aligned Movement in Kuala Lumpur. He blamed Western nations and Israel for a global rise in terrorism: "If innocent people who died in the attack on Afghanistan and those who have been dying from lack of food and medical care in Iraq are considered collaterals, are the 3,000 who died in New York and the 200 in Bali also just collaterals whose deaths are necessary for operations to succeed?" He also said: "If we think back, there was no systematic campaign of terror outside Europe until the Europeans and the Jews created a Jewish state out of Palestinian land."[87] A 2003 house hearing by the Subcommittee on East Asia and the Pacific of the U.S. House International Relations Committee (now called the House Committee on Foreign Affairs) summarises the relationship between the United States and Malaysia as follows: "Despite sometimes blunt and intemperate public remarks by Prime Minister Mahathir, U.S.-Malaysian cooperation has a solid record in areas as diverse as education, trade, military relations, and counter-terrorism."[88]

Australia

Mahathir's relationship with Australia (the closest country in the Anglosphere to Malaysia, and the one whose foreign policy is most concentrated on the region), and his relationship with Australia's political leaders, has been particularly rocky. Relationships between Mahathir and Australia's leaders reached a low point in 1993 when Paul Keating described Mahathir as "recalcitrant" for not attending the APEC summit. It is thought that Keating's description was a linguistic gaffe, and that what he had in mind was "intransigent".[89]

Singapore

Mahathir is an alumnus of the National University of Singapore. He studied at the university's King Edward VII College of Medicine between 1947 and 1953. When he and his wife were granted honorary degrees by the university in November 2018, he said that "I will always value my stay in Singapore for nearly six years." Singapore's long-time prime minister Lee Kuan Yew was also a student at the National University of Singapore.[90] However, relations with Singapore under Mahathir's tenure were stormy. Many disputed issues raised during his administration have not been resolved.[91] Issues have included:

- disputes about the Malaysia–Singapore Points of Agreement of 1990;[91]

- disputes over water prices;[91]

- the proposed replacement of the bridge Causeway bridge;[91]

- the dispute over the island Pedra Branca.[91]

On Lee Kuan Yew's death in March 2015, Mahathir wrote a blog chedet.cc entitled "Kuan Yew and I". He expressed his sorrow and grief at the loss of Lee. He said that he often disagreed with the veteran Singaporean leader but bore him no enmity for the differences of opinion on what was good for the newborn nation to thrive. He wrote that with Lee's death, ASEAN had lost the strong leadership of both Lee as well as President Suharto of Indonesia who had died earlier in 2008.[92] Many political analysts believe that with Lee's death, Mahathir is the last of the "Old Guard" of Southeast Asia.[93]

In April 2016, the 1st Anniversary of Lee Kuan Yew's death. Mahathir told the media that Singaporeans must value Lee Kuan Yew's contributions because he industrialised Singapore. He said: "That is one achievement that we need to recognise." With Lee, Mahathir "had no problems." He said that he does not view Lee "as an enemy and all that, but as a Singapore leader who had his own stand that was not the same with the stand of Malaysia."[94]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mahathir has been noted as a particular significant ally of that nation. He was influential in the establishment of an OIC summit in Karachi in 1993 to discuss the need of weapons for Bosnia during the Bosnian War. Mahathir also opened the bridge of the Malaysian-Bosnian and Herzegovinian friendship in the Bosnian capital Sarajevo.[95] On 11 November 2009, he also chaired closed-door meeting of leading investors at the Malaysia Global Business Forum – Bosnia, which was also attended by then president Haris Silajdžić.[96]

Developing world

Among developing and Islamic countries, Mahathir is generally respected.[76] This is particularly due to Malaysia's relatively high economic growth as well as Mahathir's support towards liberal Muslim values.[97] Malaysia has good relations with Indonesia,[98] and has maintained strong relations with Kazakhstan.[99]

Retirement (2003–2018)

On his retirement, Mahathir was named a Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm, allowing him to adopt the title of "Tun".[100] He pledged to leave politics "completely", rejecting an emeritus role in Abdullah's cabinet.[101] Abdullah immediately made his mark as a quieter and less adversarial premier. With much stronger religious credentials than Mahathir, he was able to beat back PAS's surge in the 1999 election, and lead the Barisan Nasional in the 2004 election to its biggest win ever, taking 199 of 219 parliamentary seats.[102]

Mahathir was the CEO and Chairman, and hence a senior adviser, to many flagship Malaysian companies such as Proton, Perdana Leadership Foundation and Malaysia's government-owned oil and gas company Petronas.[103] Mahathir and Abdullah had a major fallout over Proton in 2005. Proton's chief executive, a Mahathir ally, had been sacked by the company's board. With Abdullah's blessing, Proton then sold one of its prise assets, the motorcycle company MV Agusta, which was bought on Mahathir's advice.[104] Mahathir also criticised the awarding of import permits for foreign cars, which he claimed were causing Proton's domestic sales to suffer,[105] and attacked Abdullah for cancelling the construction of a second causeway between Malaysia and Singapore.[106] Mahathir complained that his views were not getting sufficient airing by the Malaysian press, the freedom of which he had curtailed while prime minister: he had been named one of the "Ten Worst Enemies of the Press" by the Committee to Protect Journalists for his restrictions on newspapers and occasional imprisonment of journalists.[107] He turned to the blogosphere in response, writing a column for Malaysiakini, an online media news website, and starting his own blog.[108] He unsuccessfully sought election from his local party division to be a delegate to UMNO's general assembly in 2006, where he planned to initiate a revolt against Abdullah's leadership of the party.[109] After the 2008 election, in which UMNO lost its two-thirds majority in Parliament, Mahathir resigned from the party. Abdullah was replaced by his deputy, Najib Razak, in 2009, a move that prompted Mahathir to rejoin the party.[110]

Mahathir continued to attract controversy in retirement for remarks on international affairs. He is a strident critic of Israel and has been accused of being antisemitic.[111] In his 1970 book The Malay Dilemma, Mahathir wrote "The Jews are not merely hook-nosed, but understand money instinctively," sentiments he reiterated in a 2018 BBC interview in which he also disputed the number of Jews killed in The Holocaust.[112] In a 2012 blog post, he echoed past claims by writing that "Jews rule this world by proxy."[113] Also in 2012 he stated: "I am glad to be labeled antisemitic [...] How can I be otherwise, when the Jews who so often talk of the horrors they suffered during the Holocaust show the same Nazi cruelty and hard-heartedness towards not just their enemies but even towards their allies should any try to stop the senseless killing of their Palestinian enemies."[114] Mahathir established the Kuala Lumpur Initiative to Criminalise War Forum in an effort to end war globally,[115] as well as the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Commission to investigate the activities of the United States, Israel and its allies in Iraq, Lebanon and the Palestinian territories.[116] He has also suggested that the September 11 attacks of 2001 might have been staged by the United States government.[117]

Mahathir underwent a heart bypass operation in 2007, following two heart attacks over the previous two years. He had undergone the same operation after his heart attack in 1989. After the 2007 operation, he suffered a chest infection. He was hospitalised for treatment of another chest infection in 2010.[109][118]

Return to politics

Mahathir repeatedly called for Prime Minister Najib Razak to resign.[119] On 30 August 2015, he and his wife, Siti Hasmah, attended the Bersih 4 rally, which saw tens of thousands demonstrating for Najib's resignation.[120] In 2016, Mahathir ignited several protests that culminated in the Malaysian Citizens' Declaration by himself with the help of Pakatan Harapan and NGOs to oust Najib.[121][122] Najib's response to the corruption accusations has been to tighten his grip on power by replacing the deputy prime minister, suspending two newspapers and pushing through parliament a controversial National Security Council Bill that provides the prime minister with unprecedented powers.[123][124]

Mahathir left UMNO in 2016, forming the Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (PPBM).[125][126] The new party was officially registered on 9 September 2016, and Mahathir became its chairman.[127] By 2017, he had officially joined the opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan. He was proposed as a possible chairman and prime ministerial candidate of Pakatan Harapan.[128] He assumed the position of chairman on 14 July 2017.[129]

Controversial speech on Bugis people

On 14 October 2017, referencing the 1MDB scandal, Mahathir said of Najib; "a prime minister who came from 'Bugis pirates' is now leading Malaysia". He remarked "go back to Sulawesi", which aroused discontent from the Bugis descendants in Malaysia and Indonesia who protested against him.[130] It also disappointed the Sultan of Johor and the Sultan of Selangor, who are both of Bugis descent.[131] On 8 February 2018, Mahathir's Darjah Kerabat Al-Yunusi (DK Kelantan) was revoked by the Kelantan royal house, alongside two of his Pakatan Harapan colleagues, with no reason given.[132]

2018 candidacy

On 8 January 2018, Mahathir was announced as the Pakatan Harapan opposition alliance's prime ministerial candidate for the election to be held on 9 May 2018, seeking to oust his former ally Najib. Wan Azizah, wife of his former political enemy Anwar, ran as his deputy.[133] According to the election results disclosed on 10 May 2018, Pakatan Harapan had claimed victory, thus successfully propelling him to the prime ministerial seat once again.[134] He would then seek a pardon for Anwar, in order to allow him to take over the leadership.[135][136]

Second term as prime minister

Following the historic victory of the opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan, Najib was successfully ousted from the incumbent prime ministerial seat. Mahathir hoped to be sworn in as the new prime minister by 5 pm.[137]

Concerns for a smooth power transition emerged as Najib, although admitting the defeat of his party and coalition during a press conference at 11 am, declared that no party has achieved a simple majority win (due to the fact that the opposing coalition were competing as allied individual parties, and was not successfully registered as a single unit by the Electoral Committee, who was believed to be under Najib's heavy influence during his power), thus leaving the appointment of the office to the hands of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.[138] Nevertheless, the National Palace of Malaysia had promptly issued a royal statement, confirming Mahathir Mohamad will be sworn in as the prime minister at 9:30 pm, on the same day (10 May 2018), and had strongly refuted any claims of delaying the appointment.[139] At 10 pm, Mahathir was officially sworn in as prime minister.[140]

Mahathir became the oldest currently serving state leader in the world (aged 92 years, 304 days at the time).[141] As proposed in the original plan of Pakatan Harapan, Wan Azizah ran as his deputy, and therefore became the first female deputy prime minister of Malaysia.[142] Following his appointment as prime minister, Mahathir promised to "restore the rule of law", and would make elaborate and transparent investigations on the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal possibly perpetrated by the ex-prime minister, as Mahathir told the press that if Najib has done something wrong, he would face the consequences.[143]

North Korea

Mahathir welcomed the 2018 North Korea–United States summit. He said "the world should not treat North Korean leader Kim Jong-un with skepticism and instead learn from his new attitude towards bringing about peace".[144] In a joint press conference in Tokyo with Japan, Mahathir said: "We hoped for a successful outcome from the historic meeting",[145] adding that "Malaysia will re-open their embassy in North Korea as an end to the diplomatic row over the assassination of Kim Jong-nam last year".[146]

China and Hong Kong

Mahathir said about China's treatment of its Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang, "We can condemn [China] but the fact is that the condemnation alone would not achieve anything."[147]

Mahathir said he is in the opinion that Carrie Lam should resign as the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, fearing a repeat of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests where Mainland China's authorities used soldiers from other regions to take very harsh action towards the protesters since they know the soldiers in the area will not do such things as they were the relatives of the protesters. He added that Lam already knew "the consequences of rejecting [the extradition] law" as herself was in a dilemma when she has to obey her Mainland masters.[148][149]

LGBT rights

During a lecture to students in a university in Bangkok, Thailand, in October 2018, Mahathir stated that Malaysia would not "copy" Western nations' approach towards LGBT rights, indicating that these countries were exhibiting a disregard for the institutions of the traditional family and marriage, as the value system in Malaysia is good.[150]

Killings of Jamal Khashoggi and Qasem Soleimani

Mahathir has stated that the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was unacceptable. Malaysia, he said, does not support the killing of government critics. "This is extreme cruelty, and it is not acceptable. We too have people that we do not like, but we don't kill them."[151]

On 3 January 2020, Iranian General Qasem Soleimani was assassinated by the United States, which heightened the existing tensions between the two countries. Mahathir compared the assassination of Soleimani with the killing of Jamal Khashoggi and said it was "illegal" and "immoral".[152]

2019 World Para Swimming Championships controversy

In 2017, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) granted hosting rights of the 2019 World Para Swimming Championships to Malaysia, who fought off competition from Great Britain.[153] This was done with the understanding that they would permit all qualified athletes to compete. In 2019, as part of a solidarity move with the Palestinian National Authority, Malaysia announced that they would ban Israeli athletes from the event in a move that was supported by 29 Malaysian non-governmental organizations.[154] The Malaysian Paralympic Council claimed they were following government policy, as Malaysia bans Israeli passport holders from entering the country.[155] Mahathir said that Israel is "a country which does not obey international laws" and that the world always follows what Israel says.[156] On 27 January 2019, Malaysia were stripped of their hosting rights because of the decision, and on 15 April 2019 London was announced as the replacement host.[157]

Resignation

On 23 February 2020, political parties such as BERSATU, PAS and UMNO, and Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS), as well as a faction from within the People's Justice Party led by Azmin Ali held extraordinary meetings at various locations in the country. The high-level meetings which were held concurrently fueled speculation that there was an ongoing attempt to form a new governing coalition.[158] Once the BERSATU meeting had ended, Mahathir organised a gathering at his house attended by Azmin Ali as well as party leaders from PAS, UMNO, Warisan, and GPS. In the evening, Azmin Ali together with leaders of the parties that had previously gathered at Mahathir's residence sought and were granted an audience with the Agong. Later in the night, some 131 MPs including various opposition party leaders gathered at Sheraton Hotel, Petaling Jaya for a dinner party celebrating a "consensus" among MPs.[159][160] The same night, Anwar Ibrahim confirmed to party supporters at his residence after a religious event that there was indeed an attempt to create a new governing coalition by BERSATU and a faction of the PKR.[161][162]

On the morning of the next day, Anwar Ibrahim together with the Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah Ismail, Amanah President Mat Sabu, and Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng met Mahathir at his residence to seek clarification regarding the attempted formation of a new governing coalition that involved BERSATU.[163] It was later revealed by Anwar that Mahathir had said he had nothing to do with the attempt to form a new governing coalition.[164] In the afternoon, reports surfaced that Mahathir had submitted his resignation to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.[165][166] The Agong accepted Mahathir's resignation, but appointed him as interim prime minister.[167][168][169] Anwar later stated that Mahathir had resigned despite his appeals because he refused to work with UMNO, who would be a component party of the new coalition.[170]

On 29 February, the Agong appointed Muhyiddin Yassin, the president of the Malaysian United Indigenous Party, as prime minister, determining that he was "most likely to have received the trust of the majority" of MPs. Muhyiddin was sworn in as prime minister the following day.[171]

Extradition Policies of Mahathir

Mahathir’s continued refusals to extradite Dr Zakir Naik, an Indian Islamic preacher who has been accused of inciting terrorism and money laundering by Indian authorities,[172] has led to domestic and international criticism. Mahathir has ignored Indian authorities’ pleas to extradite Naik on the grounds that he believes the preacher will not receive a fair trial in India.[173] Detractors claim that Mahathir is merely using Naik as a political pawn, given that Mahathir has extradited others from Malaysia in similar situations, including Turkish national Arif Komis and his family in August 2019.[174] The Malaysian government did not halt the deportation despite Komis holding a UNHCR refugee card, despite the family consisting of young and vulnerable children, and despite international warnings over the risk of torture to those deported to Turkey. Detractors of Mahathir have also accused him of hypocrisy in the matter given the parallel with the case of Jho Low, the Malaysian financier who is being accused of involvement in the 1MDB scandal, and who Mahathir is insisting be extradited to Malaysia. Jho Low has refused, as he claims to have no confidence in the Malaysian judicial system and does not believe he will receive a fair trial.[175] Naik has also come under fire recently for making comments against both the Malaysian Chinese and Malaysian Indians. His comments resulted in a police investigation and several Malaysian ministers calling for his expulsion, however, Mahathir has remained steadfast in his position to protect the Indian preacher.[176]

Self-proclaimed anti-Semitism

Mahathir Mohamad is a self-proclaimed anti-Semite. Among the quotes that are used to illustrate his views are: "I am glad to be labeled anti-semitic", "Jews are ruling the world by proxy", "The Jews are not merely hook-nosed, but understand money instinctively".[177] He made public his musing over the question of how might the Muslim world defeat the Jews, in a speech he made at a meeting of the Organization of the Islamic Cooperation, hosted in Kuala Lumpur: "1.3 billion Muslims cannot be defeated by a few million Jews. There must be a way. And we can only find a way if we stop to think, to assess our weaknesses and our strength, to plan, to strategize and then to counterattack. We are actually very strong. 1.3 billion people cannot be simply wiped out. The Europeans killed 6 million Jews out of 12 million. But today the Jews rule this world by proxy".[178]

Awards and recognitions

Honors of Malaysia

Malaysia :

Malaysia :

Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm (SMN) – Tun (2003)[179]

Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm (SMN) – Tun (2003)[179]

Federal Territory (Malaysia) :

Federal Territory (Malaysia) :

Grand Knight of the Order of the Territorial Crown (SUMW) – Datuk Seri Utama (2008)[179]

Grand Knight of the Order of the Territorial Crown (SUMW) – Datuk Seri Utama (2008)[179]

Johor :

Johor :

Gold Medal of the Sultan Ibrahim Medal (PIS) (1985)[180]

Gold Medal of the Sultan Ibrahim Medal (PIS) (1985)[180] Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Crown of Johor (SPMJ) – Dato' (1979)[179]

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Crown of Johor (SPMJ) – Dato' (1979)[179] Grand Commander of the Royal Family Order of Johor (DKI) (1989)[179]

Grand Commander of the Royal Family Order of Johor (DKI) (1989)[179]

Kedah :

Kedah :

Knight Grand Companion of the Order of Loyalty to the Royal House of Kedah (SSDK) – Dato' Seri (1977)[179]

Knight Grand Companion of the Order of Loyalty to the Royal House of Kedah (SSDK) – Dato' Seri (1977)[179] Kedah Supreme Order of Merit (DUK) (1988)[179]

Kedah Supreme Order of Merit (DUK) (1988)[179] Member of the Royal Family Order of Kedah (DK) (2003)[179]

Member of the Royal Family Order of Kedah (DK) (2003)[179]

Kelantan :

Kelantan :

Royal Family Order of Kelantan (DK) (2002

Royal Family Order of Kelantan (DK) (2002

Malacca :

Malacca :

Grand Commander of the Order of Malacca (DGSM) – Datuk Seri[179]

Grand Commander of the Order of Malacca (DGSM) – Datuk Seri[179] Knight Grand Commander of the Order of Malacca (DUNM) – Datuk Seri Utama[179]

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of Malacca (DUNM) – Datuk Seri Utama[179]

Negeri Sembilan :

Negeri Sembilan :

Principal Grand Knight of the Order of Loyalty to Negeri Sembilan (SPNS) – Dato' Seri Utama (1981)[179]

Principal Grand Knight of the Order of Loyalty to Negeri Sembilan (SPNS) – Dato' Seri Utama (1981)[179] Royal Family Order of Negeri Sembilan (DKNS) (1982)[180]

Royal Family Order of Negeri Sembilan (DKNS) (1982)[180]

Pahang :

Pahang :

Grand Knight of the Order of Sultan Ahmad Shah of Pahang (SSAP) – Dato' Sri (1977)[179]

Grand Knight of the Order of Sultan Ahmad Shah of Pahang (SSAP) – Dato' Sri (1977)[179]

Penang :

Penang :

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of State (DUPN) – Dato' Seri Utama (1981)[179]

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of State (DUPN) – Dato' Seri Utama (1981)[179]

Perak :

Perak :

Grand Knight of the Order of Cura Si Manja Kini (SPCM) – Dato' Seri (1981)[179]

Grand Knight of the Order of Cura Si Manja Kini (SPCM) – Dato' Seri (1981)[179]

Perlis :

Perlis :

Member of the Perlis Family Order of the Gallant Prince Syed Putra Jamalullail (DK) (1995)[179]

Member of the Perlis Family Order of the Gallant Prince Syed Putra Jamalullail (DK) (1995)[179]

Sabah :

Sabah :

Grand Commander of the Order of Kinabalu (SPDK) – Datuk Seri Panglima (1981)[179]

Grand Commander of the Order of Kinabalu (SPDK) – Datuk Seri Panglima (1981)[179]

Sarawak :

Sarawak :

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of Hornbill Sarawak (DP) – Datuk Patinggi (1980)[179]

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of Hornbill Sarawak (DP) – Datuk Patinggi (1980)[179] Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of Sarawak (SBS) – Pehin Sri (2003)[179]

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of Sarawak (SBS) – Pehin Sri (2003)[179]

Selangor :

Selangor :

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Crown of Selangor (SPMS) – Dato' Seri (1978

Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Crown of Selangor (SPMS) – Dato' Seri (1978 Royal Family Order of Selangor First Class (DK) (2003

Royal Family Order of Selangor First Class (DK) (2003

Terengganu :

Terengganu :

Member Grand Companion of the Order of Sultan Mahmud I of Terengganu (SSMT) – Dato' Seri (1982)[179]

Member Grand Companion of the Order of Sultan Mahmud I of Terengganu (SSMT) – Dato' Seri (1982)[179]

Foreign honors

Argentina :

Argentina :

Bosnia and Herzegovina :

Bosnia and Herzegovina :

Brunei :

Brunei :

Royal Family Order of Brunei 1st Class (DK (Laila Utama)) (1997)[180]

Royal Family Order of Brunei 1st Class (DK (Laila Utama)) (1997)[180]

Chile :

Chile :

Order of Merit (1991)[180]

Order of Merit (1991)[180]

Cuba :

Cuba :

Order of José Martí (1997)[180]

Order of José Martí (1997)[180]

Djibouti :

Djibouti :

- Commander of the Order of the Great Star of Djibouti (1998)[180]

Japan :

Japan :

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1991)[180]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1991)[180] Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (2018)[183]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (2018)[183]

Kuwait :

Kuwait :

Collar of the Order of Mubarak the Great (1997)[180]

Collar of the Order of Mubarak the Great (1997)[180]

Lebanon :

Lebanon :

Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit (1997)[180]

Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit (1997)[180]

Mali :

Mali :

Grand Cross of the National Order of Mali (1984)[180]

Grand Cross of the National Order of Mali (1984)[180]

Mexico :

Mexico :

Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (1991)[180]

Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (1991)[180]

Pakistan :

Pakistan :

Order of Pakistan (NPk) (2019)[184][185]

Order of Pakistan (NPk) (2019)[184][185]

Poland :

Poland :

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (2002)[180]

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (2002)[180]

Russia :

Russia :

Order of Friendship (2003)[186]

Order of Friendship (2003)[186]

South Korea :

South Korea :

Grand Gwanghwa Medal of the Order of Diplomatic Service Merit (1983)[180]

Grand Gwanghwa Medal of the Order of Diplomatic Service Merit (1983)[180]

Sweden :

Sweden :

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star (KmstkNO) (1996)[180]

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star (KmstkNO) (1996)[180]

Thailand :

Thailand :

Knight Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Order of the White Elephant (KGE) (1981)[180]

Knight Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Order of the White Elephant (KGE) (1981)[180]

Turkey :

Turkey :

Order of the Republic (2019)[187]

Order of the Republic (2019)[187]

Venezuela :

Venezuela :

Order of the Liberator (1990)[180]

Order of the Liberator (1990)[180]

Recognitions and accolades

Albania :

Albania :

India :

India :

- Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding (1994)[188]

Pakistan :

Pakistan :

- Order of Great Leader (Nishan-e-Quaid-i-Azam) (1984)[180][185]

Saudi Arabia :

Saudi Arabia :

- King Faisal International Prize for Service to Islam (1997)[180]

United Nations :

United Nations :

- U Thant Peace Award (1999)[180]

Honorary degrees

Malaysia :

Malaysia :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Management and Engineering from University of Technology, Malaysia (2003)[180]

- Honorary Litt.D. degree from International Islamic University Malaysia (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Islamic Thoughts from University of Malaya (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Engineering and Technology from PETRONAS University of Technology (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Government and Political Science from MARA University of Technology (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Law from National University of Malaysia (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Knowledge Science from Multimedia University (2004)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Global Peace and National Reconciliation from Perdana University (2018)[189]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Business Management from Asia School of Business (2019)[190]

China :

China :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from Tsinghua University (2004)[180]

Egypt :

Egypt :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Literature from Al-Azhar University (1998)[180]

Japan :

Japan :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from Meiji University (2001)[180]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Laws from Keio University (2004)[191]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (2018)[192]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from Tsukuba University (2018)[193]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from International University of Japan (2019)[194]

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Humane letters from Doshisha University (2019)[195]

Mongolia :

Mongolia :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Humanities from National University of Mongolia (1997)[180]

Qatar :

Qatar :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree from Qatar University (2019)[196]

Singapore :

Singapore :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Laws from National University of Singapore (2018)[90]

Thailand :

Thailand :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Social Leadership, Business and Politics from Rangsit University (2018)[197]

Turkey :

Turkey :

- Honorary Ph.D. degree in Political Science and Public Administration from Yildirim Beyazit University (2019)[198]

Others

- Time magazine named Mahathir as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2019.[199]

- Guinness World Records recognition – At the age of 92 years 141 days, he is now the Oldest current Prime Minister (2018) having been born on 20 December 1925.[200]

Books

- The Malay Dilemma, (1970) ISBN 981-204-355-1

- The Challenge, (1986) ISBN 967-978-091-0

- Regionalism, Globalism, and Spheres of Influence: ASEAN and the Challenge of Change into the 21st century (1989) ISBN 981-303-549-8

- The Asia That Can Say No (「NO」と言えるアジア), in collaboration with Shintaro Ishihara, (1994) ISBN 433-405-217-7

- The Pacific Rim in the 21st century, (1995)

- The Challenges of Turmoil, (1998) ISBN 967-978-652-8

- The Way Forward, (1998) ISBN 0-297-84229-3

- A New Deal for Asia, (1999)

- Islam & The Muslim Ummah, (2001) ISBN 967-978-738-9

- Globalisation and the New Realities (2002)

- Reflections on Asia, (2002) ISBN 967-978-813-X

- The Malaysian Currency Crisis: How and why it Happened, (2003) ISBN 967-978-756-7

- Achieving True Globalization, (2004) ISBN 967-978-904-7

- Islam, Knowledge, and Other Affairs, (2006) ISBN 983-3698-03-4

- Principles of Public Administration: An Introduction, (2007) ISBN 978-983-195-253-5

- Chedet.com Blog Merentasi Halangan (Bilingual), (2008) ISBN 967-969-589-1

- A Doctor in the House: The Memoirs of Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, 8 March 2011 ISBN 9789675997228.

- Doktor Umum: Memoir Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, 30 April 2012 ISBN 9789674150259. This book was the BM version of his best-selling memoir,"A Doctor in the house".

References

Notes

- ^ Mahathir's birth certificate gives his date of birth as 20 December. He was actually born on 10 July; his biographer Barry Wain explains that 20 December was an "arbitrary" date chosen by Mahathir's father for official purposes.[1]

- ^ Abdul Rahman, Hussein Onn and Abdul Razak were members of the royalty or had royal ancestry,[4] as is Abdul Razak's son Najib. Abdullah Ahmad Badawi's father and grandfather were prominent religious figures.[5]

Citations

- ^ a b c Wain 2010, p. 8

- ^ "Tun M, Father of Modern Malaysia | New Straits Times | Malaysia General Business Sports and Lifestyle News". Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 5–6

- ^ a b Wain 2010, pp. 4–5

- ^ Perlez, Jane (2 November 2003). "New Malaysian Leader's Style Stirs Optimism". New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ^ "Mahathir's Birthplace or 'Rumah Kelahiran Mahathir' | Tourism Malaysia". Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 6–7

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 10–12

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 11–13

- ^ Beech, Hannah (29 October 2006). "Not the Retiring Type". Time. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 14

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 9

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 11–13

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 19

- ^ a b Wain 2010, pp. 18–19

- ^ Morais 1982, p. 22

- ^ a b c d Tan & Vasil, p. 51

- ^ a b Wain 2010, p. 28

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 26

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 29–30

- ^ Morais 1982, p. 26

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 25

- ^ Morais 1982, p. 27

- ^ Morais 1982, pp. 28–29

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 39

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 27–28

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 33–34

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 38–40

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 40

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 38

- ^ "The exotic doctor calls it a day". The Economist. 3 November 2003. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 28

- ^ Sankaran & Hamdan 1988, pp. 18–20

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 30–31

- ^ Branigin, William (29 December 1992). "Malaysia's Monarchs of Mayhem; Accused of Murder and More, Sultans Rule Disloyal Subjects". The Washington Post.

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 32

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 203–205

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 206–207

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 51–54

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 56

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 57

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 57–59

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 97–98

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 80–89

- ^ Sankaran & Hamdan 1988, p. 50

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 40–43

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (7 February 1988). "Malay Party Ruled Illegal, Spurring Conflicts". New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 43–44

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, pp. 46–49

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 65–67

- ^ Cheah, Boon Keng (2002). Malaysia: the making of a nation. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 219. ISBN 981-230-154-2.

- ^ Kim Hoong Khong (1991). Malaysia's general election 1990: continuity, change, and ethnic politics. Institute of South East Asian Studies. pp. 15–17. ISBN 981-3035-77-3.

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 1–3

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 165

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 166

- ^ Milne & Mauzy 1999, p. 74

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 104–105

- ^ Wain 2010, p. 280

- ^ Hilley, John (2001). Malaysia: Mahathirism, hegemony and the new opposition. Zed Books. p. 256. ISBN 1-85649-918-9.

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 185–189

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 105–109

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 208–214

- ^ Stewart 2003, p. 32

- ^ Stewart 2003, pp. 64–86

- ^ Stewart 2003, pp. 106–111

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 293–299

- ^ Stewart 2003, p. 141

- ^ Stewart 2003, p. 142

- ^ Stewart 2003, pp. 140–141

- ^ Wain 2010, pp. 79–80

- ^ A., Martinez, Patricia (1 December 2001). "The Islamic State or the State of Islam in Malaysia". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 23 (3). Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wain 2010, p. 80

- ^ "Views on Jews By Malaysian: His Own Words". The Associated Press. 21 October 2003. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Bush rebukes Malaysia leader over remarks about Jews". CNN. 21 October 2003. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Spillius, Alex (31 October 2003). "Mahathir bows out with parting shot at the Jews". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Mahathir to launch war crimes tribunal". The Star (Associated Press). 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- ^ "Creativity – the key to NEM's success". The Star Online. 14 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ see Mahathir Mohamad's preface to Asia's New Crisis, edited by Frank-Jürgen Richter, Pamela Mar (eds): John Wiley & Sons, Singapore, 2004.https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0470821299

- ^ "Commanding Heights: Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad". PBS.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "BBC News – Asia-Pacific – Reform protests follow Gore's Malaysia speech". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ "GORE REMARKS ANGER MALAYSIAN LEADERS". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Butler, Steven (15 November 1998). "Turning the Tables in a Very Tawdry Trial". usnews.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ Symonds, Peter. "What Anwar Ibrahim means by "reformasi" in Malaysia" Archived 8 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine, Malaysia Today

- ^ "Madeleine Albright Sings Out". The New York Times. 2 August 1997. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Lev, Michael A. (14 November 1998). "ALBRIGHT TO MEET WIFE OF JAILED MALAYSIAN FORMER DEPUTY LEADER". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Bovard, James. Terrorism and Tyranny: Trampling Freedom, Justice, and Peace to Rid the World of Evil. St. Martin's Press, 2015. ISBN 9781466892767.

- ^ "Bali victims 'collateral damage'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 25 February 2003. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Interests and Policy Priorities in Southeast Asia". U.S. Department of State Archive (2001–2009). The Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affair. 26 March 2003. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Joseph Masilamany (29 June 2006). "Mending fences". theSun. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

- ^ a b Yusof, Amir (13 November 2018). "NUS confers honorary degree on Malaysia's PM Mahathir". Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Henedick Chng; Tanya Ong; Belmont Lay (13 May 2018). "S'pore-M'sia relations during 1981 to 2003 Mahathir era were testy". Mothership. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "Kuan Yew and I ← Chedet". chedet.cc. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.