Philippines: Difference between revisions

Wtmitchell (talk | contribs) →American rule (1898–1946): satisfy {{cn|| |

→History: actually reduced amount of written text but added 3 sentences mentioning the early states of the Philippines, however the references and data increased the space taken up even when I did reduce the displayed text in the section, this to rectify the lack of balance, as if Filipinos have no agency before Philippine independence since it shows that Filipinos only received culture, when in fact it is a 2 way process.a |

||

| Line 209: | Line 209: | ||

| doi = |

| doi = |

||

| id = |

| id = |

||

| isbn = 978-971-622-006-3 }}</ref> Some polities developed substantial trade contacts with other polities in China and Southeast Asia.<ref name="Junker1999">{{cite book|last1=Junker|first1=L|title=Raiding, Trading, and Feasting the Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms|date=1999|publisher=University of Hawaiì Press|location=Honolulu}}</ref><ref name="Miksic2009">{{Cite book |title=Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery |last=Miksic |first=John N. |publisher=Editions Didier Millet |year=2009 |isbn=978-981-4260-13-8}}</ref>{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Sals2005">{{cite book | last = Sals | first = Florent Joseph | author-link = | title = The history of Agoo : 1578–2005 | publisher = Limbagan Printhouse | date = 2005 | location = La Union | page = 80 | language = English}}</ref><ref name="JocanoJr2012">{{Cite book |title=A Question of Origins |last=Jocano |first=Felipe Jr. |date=August 7, 2012 |work=Arnis: Reflections on the History and Development of Filipino Martial Arts |publisher=Tuttle Publishing |isbn=978-1-4629-0742-7 |editor-last=Wiley |editor-first=Mark |language=en}}</ref><ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web|title=Timeline of history|url=http://valoable1.webs.com/timelineofhistory.htm|accessdate=October 9, 2009|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20091123061819/http://valoable1.webs.com/timelineofhistory.htm|archivedate=November 23, 2009}}</ref> Trade with China is believed to have begun during the [[Tang dynasty]], but grew more extensive during the [[Song dynasty]].{{sfn|Scott |1994}} By the 2nd millennium CE, some Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court, trading but without direct political or military control.{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Junker1999" /> Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu [[Majapahit]] empire.<ref name="JocanoJr2012" /><ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Osborne2004">{{cite book | last = Osborne | first = Milton | authorlink = Milton Osborne | title = Southeast Asia: An Introductory History | publisher = Allen & Unwin | date = 2004 | location = Australia | pages = | volume = | edition = Ninth | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-1-74114-448-2 }}</ref>By the 15th century, Islam was established in the [[Sulu Archipelago]] and by 1565 had reached [[Mindanao]], the [[Visayas]], and [[Luzon]].<ref name=McAmis>{{cite book |

| isbn = 978-971-622-006-3 }}</ref> Some polities developed substantial trade contacts with other polities in China and Southeast Asia.<ref name="Junker1999">{{cite book|last1=Junker|first1=L|title=Raiding, Trading, and Feasting the Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms|date=1999|publisher=University of Hawaiì Press|location=Honolulu}}</ref><ref name="Miksic2009">{{Cite book |title=Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery |last=Miksic |first=John N. |publisher=Editions Didier Millet |year=2009 |isbn=978-981-4260-13-8}}</ref>{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Sals2005">{{cite book | last = Sals | first = Florent Joseph | author-link = | title = The history of Agoo : 1578–2005 | publisher = Limbagan Printhouse | date = 2005 | location = La Union | page = 80 | language = English}}</ref><ref name="JocanoJr2012">{{Cite book |title=A Question of Origins |last=Jocano |first=Felipe Jr. |date=August 7, 2012 |work=Arnis: Reflections on the History and Development of Filipino Martial Arts |publisher=Tuttle Publishing |isbn=978-1-4629-0742-7 |editor-last=Wiley |editor-first=Mark |language=en}}</ref><ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web|title=Timeline of history|url=http://valoable1.webs.com/timelineofhistory.htm|accessdate=October 9, 2009|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20091123061819/http://valoable1.webs.com/timelineofhistory.htm|archivedate=November 23, 2009}}</ref> Trade with China is believed to have begun during the [[Tang dynasty]], but grew more extensive during the [[Song dynasty]].{{sfn|Scott |1994}} By the 2nd millennium CE, some Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court, trading but without direct political or military control.{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Junker1999" /> Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu [[Majapahit]] empire.<ref name="JocanoJr2012" /><ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Osborne2004">{{cite book | last = Osborne | first = Milton | authorlink = Milton Osborne | title = Southeast Asia: An Introductory History | publisher = Allen & Unwin | date = 2004 | location = Australia | pages = | volume = | edition = Ninth | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-1-74114-448-2 }}</ref> By the 15th century, Islam was established in the [[Sulu Archipelago]] and by 1565 had reached [[Mindanao]], the [[Visayas]], and [[Luzon]].<ref name=McAmis>{{cite book |

||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=59PnSwurWj8C&pg=PA18&dq=#v=onepage |

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=59PnSwurWj8C&pg=PA18&dq=#v=onepage |

||

|title=Malay Muslims: The History and Challenge of Resurgent Islam in Southeast Asia |

|title=Malay Muslims: The History and Challenge of Resurgent Islam in Southeast Asia |

||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

|pages=18–24, 53–61 |

|pages=18–24, 53–61 |

||

|isbn=0802849458 |

|isbn=0802849458 |

||

|accessdate=January 7, 2010}}</ref> These cultural waves established early states<ref name="JocanoJr2012" /><ref name="Jocano2001" /> such as [[Rajahnate of Maynila|Maynila]], [[Tondo (historical polity)|Tondo]], [[Namayan]], [[Caboloan|Pangasinan]], [[Rajahnate of Cebu|Cebu]], [[Madja-as]], Dapitan, [[Rajahnate of Butuan|Butuan]], [[Sultanate of Maguindanao|Cotabato]], [[Confederation of sultanates in Lanao|Lanao]], [[Sultanate of Sulu|Sulu]] and [[Ma-i]].<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Go | first1 = Bon Juan | title = Ma'I in Chinese Records – Mindoro or Bai? An Examination of a Historical Puzzle | journal = Philippine Studies | volume = 53 | issue = 1 | pages = 119–138 | publisher = Ateneo de Manila | date = 2005 | url = http://www.philippinestudies.net/ojs/index.php/ps/article/download/216/223 | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20131021221348/http://www.philippinestudies.net/ojs/index.php/ps/article/download/216/223 | archivedate = October 21, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> Abroad, Filipinos were known as [[Lucoes]], and they rose to prominence by establishing overseas communities across [[South]], [[Southeast Asia]] and East Asia, organizing trading ventures, navigation expeditions and military campaigns.<ref>Lucoes warriors aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya. SOURCE: Ibidem, page 195.</ref><ref>The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD. SOURCE: Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.</ref><ref name="Pigafetta">{{Cite book |last1 = Pigafetta |first1 = Antonio |author-link = Antonio Pigafetta |title = First voyage round the world |language = English |translator = J.A. Robertson |year = 1969 |place = Manila |publisher = Filipiniana Book Guild |orig-year = 1524}}</ref> |

|||

|accessdate=January 7, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

The early polities of the Philippine archipelago were typically characterized by a three-tier social structure: a nobility class, a class of "freemen", and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen.<ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Junker1999" /> Among the members of the nobility class were leaders who held the political office of "[[Datu]]," which was responsible for leading autonomous social groups called "[[Barangay (pre-colonial)|barangay]]" or "dulohan".<ref name="Jocano2001" /> Whenever these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement<ref name="Jocano2001" /> or a geographically looser alliance group,<ref name="Junker1999" /> the more senior or respected among them would be recognized as a "paramount datu".{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Legarda, Benito, Jr. 2001 40">{{Cite journal|author = Legarda, Benito Jr. |journal = Kinaadman (Wisdom) A Journal of the Southern Philippines |title = Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines |volume = 23 |year = 2001 |page = 40 |ref = harv}}</ref> |

The early polities of the Philippine archipelago were typically characterized by a three-tier social structure: a nobility class, a class of "freemen", and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen.<ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Junker1999" /> Among the members of the nobility class were leaders who held the political office of "[[Datu]]," which was responsible for leading autonomous social groups called "[[Barangay (pre-colonial)|barangay]]" or "dulohan".<ref name="Jocano2001" /> Whenever these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement<ref name="Jocano2001" /> or a geographically looser alliance group,<ref name="Junker1999" /> the more senior or respected among them would be recognized as a "paramount datu".{{sfn|Scott |1994}}<ref name="Jocano2001" /><ref name="Legarda, Benito, Jr. 2001 40">{{Cite journal|author = Legarda, Benito Jr. |journal = Kinaadman (Wisdom) A Journal of the Southern Philippines |title = Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines |volume = 23 |year = 2001 |page = 40 |ref = harv}}</ref> |

||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

Under Spanish rule, [[Catholic]] missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to [[Christianity]].<ref>Russell, S.D. (1999) {{cite news |url = http://www.seasite.niu.edu/crossroads/russell/christianity.htm |title = Christianity in the Philippines |accessdate = April 2, 2013}}</ref> They also founded schools, a university, hospitals, and churches.<ref>[http://www.aenet.org/manila-expo/page16.htm "The City of God: Churches, Convents and Monasteries"]. Discovering Philippines. Retrieved on July 6, 2011.</ref> To defend their settlements, the Spaniards constructed and manned a network of [[Presidio|military fortresses]] across the archipelago.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://filipinokastila.tripod.com/fort.html/|title=Fortress of Empire|author=Rene Javellana, S.J. |date=1997}}</ref> The Spanish also decreed the introduction of free public schooling in 1863.<ref>{{harvnb|Dolan|1991}}, [http://countrystudies.us/philippines/53.htm Education].</ref> Slavery was also abolished. As a result of these policies the Philippine population increased exponentially.<ref name="Gonzalez93">{{cite web |url=http://www.populstat.info/Asia/philippc.htm |title=The Philippines: historical demographic data of the whole country |accessdate=July 19, 2003 |first=Jan |last=Lahmeyer |year=1996 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303214300/http://www.populstat.info/Asia/philippc.htm |archive-date=March 3, 2016 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://1898.mforos.com/1026829/7262657-censos-de-cuba-puerto-rico-filipinas-y-espana-estudio-de-su-relacion/ |title=Censos de Cúba, Puerto Rico, Filipinas y España. Estudio de su relación |accessdate=December 12, 2010 |publisher=Voz de Galicia |year=1898 }}</ref> |

Under Spanish rule, [[Catholic]] missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to [[Christianity]].<ref>Russell, S.D. (1999) {{cite news |url = http://www.seasite.niu.edu/crossroads/russell/christianity.htm |title = Christianity in the Philippines |accessdate = April 2, 2013}}</ref> They also founded schools, a university, hospitals, and churches.<ref>[http://www.aenet.org/manila-expo/page16.htm "The City of God: Churches, Convents and Monasteries"]. Discovering Philippines. Retrieved on July 6, 2011.</ref> To defend their settlements, the Spaniards constructed and manned a network of [[Presidio|military fortresses]] across the archipelago.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://filipinokastila.tripod.com/fort.html/|title=Fortress of Empire|author=Rene Javellana, S.J. |date=1997}}</ref> The Spanish also decreed the introduction of free public schooling in 1863.<ref>{{harvnb|Dolan|1991}}, [http://countrystudies.us/philippines/53.htm Education].</ref> Slavery was also abolished. As a result of these policies the Philippine population increased exponentially.<ref name="Gonzalez93">{{cite web |url=http://www.populstat.info/Asia/philippc.htm |title=The Philippines: historical demographic data of the whole country |accessdate=July 19, 2003 |first=Jan |last=Lahmeyer |year=1996 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303214300/http://www.populstat.info/Asia/philippc.htm |archive-date=March 3, 2016 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://1898.mforos.com/1026829/7262657-censos-de-cuba-puerto-rico-filipinas-y-espana-estudio-de-su-relacion/ |title=Censos de Cúba, Puerto Rico, Filipinas y España. Estudio de su relación |accessdate=December 12, 2010 |publisher=Voz de Galicia |year=1898 }}</ref> |

||

During its rule, Spain quelled [[Philippine revolts against Spain|various indigenous revolts]], as well as defending against external military challenges<ref>[https://www.ostasien-verlag.de/zeitschriften/cr/pdf/CR_16_2017_099-120_Iaccarino.pdf “The Center of a Circle”: Manila’s Trade with East and Southeast Asia at the Turn of the Sixteenth Century By Ubaldo IACCARINO]</ref> The Philippines was maintained at a considerable cost during Spanish rule. The long war against the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]] from the West, in the 17th century, together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South and combating Japanese-Chinese [[Wokou]] piracy from the North nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.<ref>{{Harvnb|Dolan|1991}}, [http://countrystudies.us/philippines/4.htm The Early Spanish Period].</ref> Furthermore, the state of near constant wars caused a high desertion rate among the Latino soldiers sent from Mexico<ref>"In Governor Anda y Salazar’s opinion, an important part of the problem of vagrancy was the fact that Mexicans and Spanish disbanded after finishing their military or prison terms "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence."" ~CSIC riel 208 leg.14</ref> and Peru that were stationed in the Philippines |

During its rule, Spain quelled [[Philippine revolts against Spain|various indigenous revolts]], as well as defending against external military challenges<ref>[https://www.ostasien-verlag.de/zeitschriften/cr/pdf/CR_16_2017_099-120_Iaccarino.pdf “The Center of a Circle”: Manila’s Trade with East and Southeast Asia at the Turn of the Sixteenth Century By Ubaldo IACCARINO]</ref> The Philippines was maintained at a considerable cost during Spanish rule. The long war against the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]] from the West, in the 17th century, together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South and combating Japanese-Chinese [[Wokou]] piracy from the North nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.<ref>{{Harvnb|Dolan|1991}}, [http://countrystudies.us/philippines/4.htm The Early Spanish Period].</ref> Furthermore, the state of near constant wars caused a high desertion rate among the Latino soldiers sent from Mexico<ref>"In Governor Anda y Salazar’s opinion, an important part of the problem of vagrancy was the fact that Mexicans and Spanish disbanded after finishing their military or prison terms "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence."" ~CSIC riel 208 leg.14</ref> and Peru that were stationed in the Philippines <ref>Garcıa de los Arcos, "Grupos etnicos," ´ 65–66</ref><ref>CSIC ser. Consultas riel 301 leg.8 (1794)</ref> and is also applied to Filipino warriors and laborers levied by Spain. Due to repeated wars, lack of wages, dislocation and near starvation almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America and the warriors and laborers recruited locally either died or deserted.<ref>The Diversity and Reach of the Manila Slave Market Page 36</ref><ref>"The descendants of Mexican mestizos and native Filipinos were numerous but unaccounted for because they were mostly the result of informal liasons." ~Garcia de los Arcos, Forzados, 238</ref> Immigration blurred the racial caste system Spain maintained in towns and cities.<ref name="ReferenceC">Tomás de Comyn, general manager of the Compañia Real de Filipinas, in 1810 estimated that out of a total population of 2,515,406, "the European Spaniards, and Spanish creoles and mestizos do not exceed 4,000 persons of both sexes and all ages, and the distinct castes or modifications known in America under the name of mulatto, quarteroons, etc., although found in the Philippine Islands, are generally confounded in the three classes of pure Indians, Chinese mestizos and Chinese." In other words, the Mexicans who had arrived in the previous century had so intermingled with the local population that distinctions of origin had been forgotten by the 19th century. The Mexicans who came with Legázpi and aboard succeeding vessels had blended with the local residents so well that their country of origin had been erased from memory.</ref> Increasing difficulty in governing the Philippines led to the Royal Fiscal of Manila writing to [[King Charles III of Spain]], advising him to abandon the colony. However, this was successfully opposed by the religious and missionary orders that argued that the Philippines was a launching pad for further religious conversion in the Far East.<ref>Blair, E., Robertson, J., & Bourne, E. (1903). The Philippine islands, 1493–1803 : explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century. Cleveland, Ohio.</ref> |

||

[[File:Intramuros_cannon.JPG|thumb|left|Spanish artillery along the walls of [[Intramuros]] to protect the city from local revolts and foreign invaders.]] |

[[File:Intramuros_cannon.JPG|thumb|left|Spanish artillery along the walls of [[Intramuros]] to protect the city from local revolts and foreign invaders.]] |

||

The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy provided by the Spanish Crown, usually paid through the provision of 75 tons of silver bullion being sent from the Americas.<ref>Bonialian, 2012{{cnf|date=June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Cole|first=Jeffrey A.|title=The Potosí mita, 1573–1700 : compulsory Indian labor in the Andes|year=1985|publisher=Stanford University Press|location=Stanford, Calif.|isbn=978-0804712569|pages=20}}</ref> Financial constraints meant the 200-year-old fortifications in Manila did not see significant change after being first built by the early Spanish colonizers.<ref name=tracy1995p12p55>{{Harvnb|Tracy|1995|pp=12, 55}}{{cnf|date=January 2019}}</ref> [[British occupation of Manila|British forces occupied Manila]] from 1762 to 1764 during the [[Seven Years' War]], however they were unable to extend their conquest outside of Manila as the Filipinos stayed loyal to the remaining Spanish community outside Manila. Spanish rule was restored through the [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|1763 Treaty of Paris]].<ref name=Agoncillo /><ref name=Halili>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gUt5v8ET4QYC&pg=PA119 |title=Philippine History |last=Halili |first=Maria Christine N. |publisher=Rex Bookstore |year=2004 |pages=119–120 |isbn=978-971-23-3934-9 }}</ref><ref name=DeBorja>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xXpiujH2uOwC&pg=PA81 |title=Basques in the Philippines |last=de Borja |first=Marciano R. |publisher=University of Nevada Press |year=2005 |pages=81–83 |isbn=978-0-87417-590-5 }}</ref> The [[Spanish–Moro conflict]] lasted for several hundred years. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Spain conquered portions of [[Mindanao]] and the [[Moro people|Moro]] Muslims in the [[Sulu Sultanate]] formally recognized Spanish sovereignty.{{Citation needed|date=May 2020}} |

The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy provided by the Spanish Crown, usually paid through the provision of 75 tons of silver bullion being sent from the Americas.<ref>Bonialian, 2012{{cnf|date=June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Cole|first=Jeffrey A.|title=The Potosí mita, 1573–1700 : compulsory Indian labor in the Andes|year=1985|publisher=Stanford University Press|location=Stanford, Calif.|isbn=978-0804712569|pages=20}}</ref> Financial constraints meant the 200-year-old fortifications in Manila did not see significant change after being first built by the early Spanish colonizers.<ref name=tracy1995p12p55>{{Harvnb|Tracy|1995|pp=12, 55}}{{cnf|date=January 2019}}</ref> [[British occupation of Manila|British forces occupied Manila]] from 1762 to 1764 during the [[Seven Years' War]], however they were unable to extend their conquest outside of Manila as the Filipinos stayed loyal to the remaining Spanish community outside Manila. Spanish rule was restored through the [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|1763 Treaty of Paris]].<ref name=Agoncillo /><ref name=Halili>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gUt5v8ET4QYC&pg=PA119 |title=Philippine History |last=Halili |first=Maria Christine N. |publisher=Rex Bookstore |year=2004 |pages=119–120 |isbn=978-971-23-3934-9 }}</ref><ref name=DeBorja>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xXpiujH2uOwC&pg=PA81 |title=Basques in the Philippines |last=de Borja |first=Marciano R. |publisher=University of Nevada Press |year=2005 |pages=81–83 |isbn=978-0-87417-590-5 }}</ref> The [[Spanish–Moro conflict]] lasted for several hundred years. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Spain conquered portions of [[Mindanao]] and the [[Moro people|Moro]] Muslims in the [[Sulu Sultanate]] formally recognized Spanish sovereignty.{{Citation needed|date=May 2020}} |

||

In the 19th century, Philippine ports opened to world trade and shifts started occurring within Filipino society. Many [[criollo people|Spaniards born in the Philippines]]<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/38269/38269-h/38269-h.htm#pb139 |title=A History of the Philippines |last=Barrows |first=David |year=2014 |volume=1 |page=179 |quote=Within the walls, there were some six hundred houses of a private nature, most of them built of stone and tile, and an equal number outside in the suburbs, or ''{{lang|es|arrabales}}'', all occupied by Spaniards (''{{lang|es|todos son vivienda y poblacion de los Españoles}}''). This gives some twelve hundred Spanish families or establishments, exclusive of the religious, who in Manila numbered at least one hundred and fifty, the garrison, at certain times, about four hundred trained Spanish soldiers who had seen service in Holland and the Low Countries, and the official classes.}}</ref> and [[mestizos|those of mixed ancestry]] were wealthy, and an influx of [[Latin American Asian|Hispanic American]] immigrants opened up government positions traditionally held by [[Peninsulares|Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula]]. However, ideas of rebellion and independence began to spread through the islands. Many Latin-Americans<ref>"Officers in the army of the Philippines were almost totally composed of Americans," observed the Spanish historian José Montero y Vidal. "They received in great disgust the arrival of peninsular officers as reinforcements, partly because they supposed they would be shoved aside in the promotions and partly because of racial antagonisms."</ref> and Criollos staffed the army of Spain in the Philippines. However, the onset of the [[Latin American wars of independence]] led to doubts about their loyalty. This was compounded by a Mexican of Filipino descent, [[Isidoro Montes de Oca]], becoming captain-general to the revolutionary leader [[Vicente Guerrero]] during the [[Mexican War of Independence]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ezilon.com/cgi-bin/information/exec/view.cgi|archiveurl=https://archive.today/20121209185353/http://www.ezilon.com/cgi-bin/information/exec/view.cgi?archive=1&num=476|url-status=dead|archivedate=December 9, 2012|title=Filipinos in Mexican history|access-date=August 13, 2019}}</ref><ref>Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación. {{ISBN|970-26-0797-3}}.</ref><ref>González Davíla Amado. Geografía del Estado de Guerrero y síntesis histórica 1959. México D.F.; ed. Quetzalcóatl.</ref> To prevent the union of |

In the 19th century, Philippine ports opened to world trade and shifts started occurring within Filipino society. Many [[criollo people|Spaniards born in the Philippines]]<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/38269/38269-h/38269-h.htm#pb139 |title=A History of the Philippines |last=Barrows |first=David |year=2014 |volume=1 |page=179 |quote=Within the walls, there were some six hundred houses of a private nature, most of them built of stone and tile, and an equal number outside in the suburbs, or ''{{lang|es|arrabales}}'', all occupied by Spaniards (''{{lang|es|todos son vivienda y poblacion de los Españoles}}''). This gives some twelve hundred Spanish families or establishments, exclusive of the religious, who in Manila numbered at least one hundred and fifty, the garrison, at certain times, about four hundred trained Spanish soldiers who had seen service in Holland and the Low Countries, and the official classes.}}</ref> and [[mestizos|those of mixed ancestry]] were wealthy, and an influx of [[Latin American Asian|Hispanic American]] immigrants opened up government positions traditionally held by [[Peninsulares|Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula]]. However, ideas of rebellion and independence began to spread through the islands. Many Latin-Americans<ref>"Officers in the army of the Philippines were almost totally composed of Americans," observed the Spanish historian José Montero y Vidal. "They received in great disgust the arrival of peninsular officers as reinforcements, partly because they supposed they would be shoved aside in the promotions and partly because of racial antagonisms."</ref> and Criollos staffed the army of Spain in the Philippines. However, the onset of the [[Latin American wars of independence]] led to doubts about their loyalty. This was compounded by a Mexican of Filipino descent, [[Isidoro Montes de Oca]], becoming captain-general to the revolutionary leader [[Vicente Guerrero]] during the [[Mexican War of Independence]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ezilon.com/cgi-bin/information/exec/view.cgi|archiveurl=https://archive.today/20121209185353/http://www.ezilon.com/cgi-bin/information/exec/view.cgi?archive=1&num=476|url-status=dead|archivedate=December 9, 2012|title=Filipinos in Mexican history|access-date=August 13, 2019}}</ref><ref>Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación. {{ISBN|970-26-0797-3}}.</ref><ref>González Davíla Amado. Geografía del Estado de Guerrero y síntesis histórica 1959. México D.F.; ed. Quetzalcóatl.</ref> To prevent the union of both Latinos and Filipinos in rebellion against the empire, the Latino and Criollo officers stationed in the Philippines were soon replaced by Peninsular officers born in Spain. These Peninsular officers were often less committed to the people they were assigned to protect and were often predatory, wanting to enrich themselves before returning to Spain, putting the interests of the metropolis over the interest of the natives.{{Citation needed|date=May 2020}} |

||

[[File:Katipuneros.jpg|thumb|Photograph of armed Filipino revolutionaries known as ''[[Katipunan|Katipuneros]]''.]] |

[[File:Katipuneros.jpg|thumb|Photograph of armed Filipino revolutionaries known as ''[[Katipunan|Katipuneros]]''.]] |

||

Revision as of 16:53, 10 June 2020

Republic of the Philippines Republika ng Pilipinas (Filipino) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa"[1] "For God, People, Nature and Country" | |

| Anthem: Lupang Hinirang (Template:Lang-en) | |

| Great Seal Dakilang Sagisag ng Pilipinas (Filipino) Great Seal of the Philippines | |

| Capital | City of Manilaa 14°35′N 120°58′E / 14.583°N 120.967°E |

| Largest city | Quezon City 14°38′N 121°02′E / 14.633°N 121.033°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized regional languages | |

| Protected auxiliary languages | |

| Other recognized languages | Filipino Sign Language |

| Ethnic groups (2015) | |

| Religion | [5] |

| Demonym(s) | Filipino (masculine or neutral) Filipina (feminine) Pinoy (colloquial masculine or neutral) Pinay (colloquial feminine) |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Rodrigo Duterte | |

| Maria Leonor Robredo | |

| Vicente Sotto III | |

| Alan Peter Cayetano | |

| Diosdado Peralta | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from the United States | |

| June 12, 1898 | |

| December 10, 1898 | |

| July 4, 1946 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 300,000[6][7] km2 (120,000 sq mi) (72nd) |

• Water (%) | 0.61[8] (inland waters) |

• Land | 298,170 |

| Population | |

• 2015 census | 100,981,437[9] (13th) |

• Density | 336/km2 (870.2/sq mi) (47th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $1.110 trillion[10] (27th) |

• Per capita | $10,094[10] (112th (2019)) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $383 billion[10] (32nd) |

• Per capita | $3,484[10] (125th (2019)) |

| Gini (2015) | medium inequality (44th) |

| HDI (2018) | high (106th) |

| Currency | Philippine peso (₱) (PHP) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| Date format |

|

| Drives on | right,[13] formerly left before 1947/1948 |

| Calling code | +63 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH |

| Internet TLD | .ph |

| |

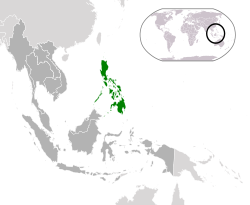

The Philippines (/ˈfɪləpiːnz/ ; Template:Lang-fil [ˌpɪlɪˈpinɐs] or Filipinas [fɪlɪˈpinɐs]), officially the Republic of the Philippines (Template:Lang-fil),[a] is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Situated in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of about 7,641 islands[16] that are broadly categorized under three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. The capital city of the Philippines is Manila and the most populous city is Quezon City, both within the single urban area of Metro Manila.[17] Bounded by the South China Sea on the west, the Philippine Sea on the east and the Celebes Sea on the southwest, the Philippines shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Japan to the northeast, Palau to the east, Indonesia to the south, Malaysia and Brunei to the southwest, Vietnam to the west, and China to the northwest.

The Philippines' location on the Pacific Ring of Fire and close to the equator makes the country prone to earthquakes and typhoons, but also endows it with abundant natural resources and some of the world's greatest biodiversity. The Philippines is the world's fifth-largest island country with an area of 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi).[18][6][7] As of 2015, it had a population of at least 100 million.[9] As of January 2018[update], it is the eighth-most populated country in Asia and the 13th-most populated country in the world. Approximately 10 million additional Filipinos lived overseas as of 2013,[19] comprising one of the world's largest diasporas. Multiple ethnicities and cultures are found throughout the islands. In prehistoric times, Negritos were some of the archipelago's earliest inhabitants. They were followed by successive waves of Austronesian peoples.[20] Exchanges with Malay, Indian, Arab and Chinese nations occurred. Subsequently, various competing maritime states were established under the rule of datus, rajahs, sultans and lakans.

The arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer leading a fleet for the Spanish, marked the beginning of Hispanic colonization. In 1543, Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos named the archipelago Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain. In 1565, the first Hispanic settlement in the archipelago was established,[21] and the Philippines became part of the Spanish Empire for more than 300 years. During this time, Catholicism became the dominant religion, and Manila became the western hub of the trans-Pacific trade.[22] In 1896 the Philippine Revolution began, which then became entwined with the 1898 Spanish–American War. Spain ceded the territory to the United States, while Filipino rebels declared the First Philippine Republic. The ensuing Philippine–American War ended with the United States establishing control over the territory, which they maintained until the Japanese invasion of the islands during World War II. Following liberation, the Philippines became an independent country in 1946. Since then, the unitary sovereign state has often had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of a dictatorship by a non-violent revolution.[23]

The Philippines is a founding member of the United Nations, World Trade Organization, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and the East Asia Summit. It also hosts the headquarters of the Asian Development Bank.[24] The Philippines is considered to be an emerging market and a newly industrialized country,[25] which has an economy transitioning from being based on agriculture to being based more on services and manufacturing.[26]

Etymology

The Philippines was named in honor of King Philip II of Spain. Spanish explorer Ruy López de Villalobos, during his expedition in 1542, named the islands of Leyte and Samar Felipinas after the then-Prince of Asturias. Eventually the name Las Islas Filipinas would be used to cover all the islands of the archipelago. Before that became commonplace, other names such as Islas del Poniente (Islands of the West) and Magellan's name for the islands, San Lázaro, were also used by the Spanish to refer to the islands.[27][28][29][30][31]

The official name of the Philippines has changed several times in the course of its history. During the Philippine Revolution, the Malolos Congress proclaimed the establishment of the República Filipina or the Philippine Republic. From the period of the Spanish–American War (1898) and the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) until the Commonwealth period (1935–1946), American colonial authorities referred to the country as the Philippine Islands, a translation of the Spanish name.[32] Since the end of World War II, the official name of the country has been the Republic of the Philippines. Philippines, with or without the definite article, has steadily gained currency as the common name since being the name used in Article VI of the 1898 Treaty of Paris.[33]

History

Prehistory (pre–900)

There is evidence of early hominins, such as Homo luzonensis, living in what is now the Philippines as early as 709,000 years ago.[34] The oldest modern human remains found on the islands is the Tabon Man of Palawan, carbon-dated to 47,000 ± 11–10,000 years ago.[35] The Tabon man is presumably a Negrito, who were among the archipelago's earliest inhabitants, descendants of the first human migrations out of Africa via the coastal route along southern Asia to the now sunken landmasses of Sundaland and Sahul.[36]

The first Austronesians reached the Philippines at around 2200 BC, settling the Batanes Islands and northern Luzon. From there, they rapidly spread downwards to the rest of the islands of the Philippines and Southeast Asia.[37][38][39] They assimilated earlier Australo-Melanesian groups (the Negritos) which arrived during the Paleolithic, resulting in the modern Filipino ethnic groups which display various ratios of genetic admixture between Austronesian and Negrito groups.[40] Jade artifacts have been found dated to 2000 BC,[41][42] with the lingling-o jade items crafted in Luzon from raw materials originating Taiwan.[43] By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the archipelago had developed into four kinds of social groups: hunter-gatherer tribes, warrior societies, highland plutocracies, and port principalities.[44]

Precolonial period (900–1521)

The earliest known surviving written record found in the Philippines is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription.[45] By the 1300s, a number of the large coastal settlements had emerged as trading centers, and became the focal point of societal changes.[46] Some polities developed substantial trade contacts with other polities in China and Southeast Asia.[47][48][49][50][51][52] Trade with China is believed to have begun during the Tang dynasty, but grew more extensive during the Song dynasty.[49] By the 2nd millennium CE, some Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court, trading but without direct political or military control.[49][47] Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu Majapahit empire.[51][46][53] By the 15th century, Islam was established in the Sulu Archipelago and by 1565 had reached Mindanao, the Visayas, and Luzon.[54] These cultural waves established early states[51][46] such as Maynila, Tondo, Namayan, Pangasinan, Cebu, Madja-as, Dapitan, Butuan, Cotabato, Lanao, Sulu and Ma-i.[55] Abroad, Filipinos were known as Lucoes, and they rose to prominence by establishing overseas communities across South, Southeast Asia and East Asia, organizing trading ventures, navigation expeditions and military campaigns.[56][57][58]

The early polities of the Philippine archipelago were typically characterized by a three-tier social structure: a nobility class, a class of "freemen", and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen.[46][47] Among the members of the nobility class were leaders who held the political office of "Datu," which was responsible for leading autonomous social groups called "barangay" or "dulohan".[46] Whenever these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement[46] or a geographically looser alliance group,[47] the more senior or respected among them would be recognized as a "paramount datu".[49][46][59]

Spanish rule (1565–1898)

In 1521, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the area, claimed the islands for Spain, and was then killed at the Battle of Mactan.[60] Colonization began when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from Mexico in 1565, establishing control of Cebu, Panay, and Luzon.[61] The Spaniards established Manila, at what is now Intramuros, as the capital of the Spanish East Indies in 1571.[62] The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista,[63]

Spanish rule brought what is now the Philippines into a single unified administration. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain, and then was administered directly from Madrid following the Mexican War of Independence.[citation needed] The Manila galleons, the largest wooden ships ever built, were constructed in Bicol and Cavite.[64]

Under Spanish rule, Catholic missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity.[65] They also founded schools, a university, hospitals, and churches.[66] To defend their settlements, the Spaniards constructed and manned a network of military fortresses across the archipelago.[67] The Spanish also decreed the introduction of free public schooling in 1863.[68] Slavery was also abolished. As a result of these policies the Philippine population increased exponentially.[69][70]

During its rule, Spain quelled various indigenous revolts, as well as defending against external military challenges[71] The Philippines was maintained at a considerable cost during Spanish rule. The long war against the Dutch from the West, in the 17th century, together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South and combating Japanese-Chinese Wokou piracy from the North nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.[72] Furthermore, the state of near constant wars caused a high desertion rate among the Latino soldiers sent from Mexico[73] and Peru that were stationed in the Philippines [74][75] and is also applied to Filipino warriors and laborers levied by Spain. Due to repeated wars, lack of wages, dislocation and near starvation almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America and the warriors and laborers recruited locally either died or deserted.[76][77] Immigration blurred the racial caste system Spain maintained in towns and cities.[78] Increasing difficulty in governing the Philippines led to the Royal Fiscal of Manila writing to King Charles III of Spain, advising him to abandon the colony. However, this was successfully opposed by the religious and missionary orders that argued that the Philippines was a launching pad for further religious conversion in the Far East.[79]

The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy provided by the Spanish Crown, usually paid through the provision of 75 tons of silver bullion being sent from the Americas.[80][81] Financial constraints meant the 200-year-old fortifications in Manila did not see significant change after being first built by the early Spanish colonizers.[82] British forces occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764 during the Seven Years' War, however they were unable to extend their conquest outside of Manila as the Filipinos stayed loyal to the remaining Spanish community outside Manila. Spanish rule was restored through the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[83][84][85] The Spanish–Moro conflict lasted for several hundred years. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Spain conquered portions of Mindanao and the Moro Muslims in the Sulu Sultanate formally recognized Spanish sovereignty.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, Philippine ports opened to world trade and shifts started occurring within Filipino society. Many Spaniards born in the Philippines[86] and those of mixed ancestry were wealthy, and an influx of Hispanic American immigrants opened up government positions traditionally held by Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula. However, ideas of rebellion and independence began to spread through the islands. Many Latin-Americans[87] and Criollos staffed the army of Spain in the Philippines. However, the onset of the Latin American wars of independence led to doubts about their loyalty. This was compounded by a Mexican of Filipino descent, Isidoro Montes de Oca, becoming captain-general to the revolutionary leader Vicente Guerrero during the Mexican War of Independence.[88][89][90] To prevent the union of both Latinos and Filipinos in rebellion against the empire, the Latino and Criollo officers stationed in the Philippines were soon replaced by Peninsular officers born in Spain. These Peninsular officers were often less committed to the people they were assigned to protect and were often predatory, wanting to enrich themselves before returning to Spain, putting the interests of the metropolis over the interest of the natives.[citation needed]

Revolutionary sentiments were stoked in 1872 after three activist Catholic priests were accused of sedition and executed.[91][92] This would inspire a propaganda movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, and Mariano Ponce, lobbying for political reforms in the Philippines. Rizal was eventually executed on December 30, 1896, on charges of rebellion. This radicalized many who had previously been loyal to Spain.[93] As attempts at reform met with resistance, Andrés Bonifacio in 1892 established the militant secret society called the Katipunan, who sought independence from Spain through armed revolt.[94]

Bonifacio and the Katipunan started the Philippine Revolution in 1896. A faction of the Katipunan, the Magdalo of Cavite province, eventually came to challenge Bonifacio's position as the leader of the revolution and Emilio Aguinaldo took over. In 1898, the Spanish–American War began, and this war reached Spanish forces in the Philippines. Aguinaldo declared Philippine independence from Spain in Kawit, Cavite, on June 12, 1898, and the First Philippine Republic was declared in the Barasoain Church in the following year.[83]

American rule (1898–1946)

The islands were ceded by Spain to the United States alongside Puerto Rico and Guam as a result of the latter's victory in the Spanish–American War.[95] As it became increasingly clear the United States would not recognize the nascent First Philippine Republic, the Philippine–American War broke out.[96] The war resulted in the deaths of a minimum of 200,000 and a maximum of 1 million Filipino civilians, mostly due to famine and disease.[97] After the defeat of the First Philippine Republic, the archipelago was administered under an American Insular Government.[98] The Americans then suppressed other rebellious proto-states: mainly, the waning Sultanate of Sulu, as well as the insurgent Tagalog Republic and the Republic of Zamboanga.[99][100]

During this era, a renaissance in Philippine culture occurred, including an expansion of Philippine cinema and literature.[101][102][103] Daniel Burnham built an architectural plan for Manila which would have transformed it into a modern city.[104] In 1935, the Philippines was granted Commonwealth status with Manuel Quezon as president and Sergio Osmeña as vice president. He designated a national language and introduced women's suffrage and land reform.[105][106]

Plans for independence over the next decade were interrupted by World War II when the Japanese Empire invaded and the Second Philippine Republic, under Jose P. Laurel, was established as a puppet state.[107]

In a report by Karl L. Rankin From mid-1942 through mid-1944, Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by large-scale underground guerrilla activity.[108][109] The largest naval battle in history, according to gross tonnage sunk, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, occurred when Allied forces started the liberation of the Philippines from the Japanese Empire.[110][111] Many atrocities and war crimes were committed during the war, including the Bataan Death March and the Manila massacre.[112][113] Allied troops defeated the Japanese in 1945. By the end of the war it is estimated that over a million Filipinos had died.[114][115][116] On October 11, 1945, the Philippines became one of the founding members of the United Nations.[117]

Third Republic (1946–65)

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines was officially recognized by the United States as an independent nation through the Treaty of Manila, during the presidency of Manuel Roxas.[8]

Efforts to end the Hukbalahap Rebellion began during Elpidio Quirino's term,[118] however, it was only during Ramon Magsaysay's presidency was the movement decimated.[119] Magsaysay's successor, Carlos P. Garcia, initiated the Filipino First Policy,[120] which was continued by Diosdado Macapagal, with celebration of Independence Day moved from July 4 to June 12, the date of Emilio Aguinaldo's declaration,[121][122] and pursuit of a claim on the eastern part of North Borneo.[123][124]

Marcos era (1965–86)

In 1965, Macapagal lost the presidential election to Ferdinand Marcos. Early in his presidency, Marcos initiated numerous infrastructure projects but, together with his wife Imelda, was accused of massive corruption and embezzling billions of dollars in public funds.[125] Nearing the end of his term, Marcos declared Martial Law on September 21, 1972.[126] This period of his rule was characterized by political repression, censorship, and human rights violations.[127]

On August 21, 1983, Marcos' chief rival, opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr., was assassinated on the tarmac at Manila International Airport. Marcos eventually called snap presidential elections in 1986.[128] Marcos was proclaimed the winner, but the results were widely regarded as fraudulent.[129] Resulting protest led to the People Power Revolution,[130] which forced Marcos and his allies to flee Hawaii and installed Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino, as president.[128]

Fifth Republic (1986–present)

The return of democracy and government reforms beginning in 1986 were hampered by national debt, government corruption, coup attempts, disasters, a persistent communist insurgency,[131] and a military conflict with Moro separatists,[132] during Corazon Aquino's administration. The administration also faced a series of natural disasters, including the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991.[133][134] Aquino was succeeded by Fidel V. Ramos whose modest economic performance, at 3.6% growth rate,[135][136] was overshadowed by the onset of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[137][138]

Ramos' successor, Joseph Estrada was overthrown by the 2001 EDSA Revolution and he was succeeded by his Vice President, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on January 20, 2001.[139] Arroyo's 9-year administration was tainted by graft and political scandals.[140][141][142][143] On November 23, 2009, 34 journalists and several civilians were massacred in Maguindanao.[144][145]

During Benigno Aquino III's administration, a clash which took place in Mamasapano, Maguindanao killed 44 members of the Philippine National Police-Special Action Force that put the efforts to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law into law in an impasse.[146][147]

Former Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte won the 2016 presidential election, becoming the first president from Mindanao.[148][149] Duterte launched an intensified anti-drug campaign.[150][151][152][153] The implementation of the Bangsamoro Organic Law led to the creation of the autonomous Bangsamoro region in Mindanao.[154][155]

Geography and environment

The Philippines is an archipelago composed of about 7,641 islands[156] with a total land area, including inland bodies of water, of 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi).[6][7] This makes it the 5th largest island country in the world.[18] The 36,289 kilometers (22,549 mi) of coastline makes it the country with the fifth longest coastline in the world.[157][158] The Exclusive economic zone of the Philippines covers 2,263,816 km2 (874,064 sq mi).[159] It is located between 116° 40', and 126° 34' E longitude and 4° 40' and 21° 10' N latitude and is bordered by the Philippine Sea[160] to the east, the South China Sea[161] to the west, and the Celebes Sea[162] to the south. The island of Borneo[163] is located a few hundred kilometers southwest and Taiwan is located directly to the north. The Moluccas and Sulawesi are located to the south-southwest and Palau is located to the east of the islands.[157]

Most of the mountainous islands are covered in tropical rainforest and volcanic in origin. The highest mountain is Mount Apo. It measures up to 2,954 meters (9,692 ft) above sea level and is located on the island of Mindanao.[164][165] The Galathea Depth in the Philippine Trench is the deepest point in the country and the third deepest in the world. The trench is located in the Philippine Sea.[166]

The longest river is the Cagayan River in northern Luzon.[167] Manila Bay, upon the shore of which the capital city of Manila lies, is connected to Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, by the Pasig River. Subic Bay, the Davao Gulf, and the Moro Gulf are other important bays. The San Juanico Strait separates the islands of Samar and Leyte but it is traversed by the San Juanico Bridge.[168]

Situated on the western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines experiences frequent seismic and volcanic activity. The Benham Plateau to the east in the Philippine Sea is an undersea region active in tectonic subduction.[169] Around 20 earthquakes are registered daily, though most are too weak to be felt. The last major earthquake was the 1990 Luzon earthquake.[170]

There are many active volcanoes such as the Mayon Volcano, Mount Pinatubo, and Taal Volcano. The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in June 1991 produced the second largest terrestrial eruption of the 20th century.[171] Not all notable geographic features are so violent or destructive. A more serene legacy of the geological disturbances is the Puerto Princesa Subterranean River, the area represents a habitat for biodiversity conservation, the site also contains a full mountain-to-the-sea ecosystem and has some of the most important forests in Asia.[172]

Due to the volcanic nature of the islands, mineral deposits are abundant. The country is estimated to have the second-largest gold deposits after South Africa giving credence to the talk that the Philippines was the Biblical Ophir[173] and the country also has one of the largest copper deposits in the world.[174] Palladium, originally discovered in South America, was found to have the world's largest deposits in the Philippines too.[175][176] Romblon island also possesses the most diversified, high quality and hardest marble in the world and is available in at least 7 colors mainly: brown, grey, rust, white, green, black and orange.[177] The country is also rich in nickel, chromite, and zinc. Despite this, poor management, high population density, a desire to protect indigenous communities from exploitation, and an extremely ardent environmental consciousness have resulted in these mineral resources remaining largely untapped.[174][178] The unstable seismologic that created these minerals, such as frequent volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and landslides, continue to affect the country.[179] Geothermal energy is a product of volcanic activity that the Philippines has harnessed more successfully. The Philippines is the world's second-biggest geothermal producer behind the United States, with 18% of the country's electricity needs being met by geothermal power.[180]

Biodiversity

The Philippines is a megadiverse country.[181][182][183] Around 1,100 land vertebrate species can be found in the Philippines including over 100 mammal species and 170 bird species not thought to exist elsewhere.[184] The Philippines has among the highest rates of discovery in the world with sixteen new species of mammals discovered in the last ten years. Because of this, the rate of endemism for the Philippines has risen and likely will continue to rise.[185] Native mammals include the palm civet cat, the dugong, the cloud rat and the Philippine tarsier associated with Bohol.

Although the Philippines lacks large mammalian predators, it does have some very large reptiles such as pythons and cobras, together with gigantic saltwater crocodiles. The largest crocodile in captivity, known locally as Lolong, was captured in the southern island of Mindanao.[186][187] The national bird, known as the Philippine eagle, has the longest body of any eagle; it generally measures 86 to 102 cm (2.82 to 3.35 ft) in length and weighs 4.7 to 8.0 kg (10.4 to 17.6 lb).[188][189] The Philippine eagle is part of the family Accipitridae and is endemic to the rainforests of Luzon, Samar, Leyte and Mindanao.

Philippine maritime waters encompass as much as 2,200,000 square kilometers (849,425 sq mi) producing unique and diverse marine life, an important part of the Coral Triangle, a territory shared with other countries.[190] The total number of corals and marine fish species was estimated at 500 and 2,400 respectively.[191][184] New records[192][193] and species discoveries[194][195][196] continuously increase these numbers, underlining the uniqueness of the marine resources in the Philippines. The Tubbataha Reef in the Sulu Sea was declared a World Heritage Site in 1993. Philippine waters also sustain the cultivation of pearls, crabs, and seaweeds.[191][197] One rare species of oyster, Pinctada maxima which is indigenous to the Philippines, is unique since its pearls are naturally golden in color.[198] The golden pearl from the Pinctada maxima is considered the national gem of the Philippines.[199]

With an estimated 13,500 plant species in the country, 3,200 of which are unique to the islands,[184] Philippine rainforests boast an array of flora, including many rare types of orchids and rafflesia.[200][201] Deforestation, often the result of illegal logging, is an acute problem in the Philippines. Forest cover declined from 70% of the Philippines's total land area in 1900 to about 18.3% in 1999.[202] Many species are endangered and scientists say that Southeast Asia, which the Philippines is part of, faces a catastrophic extinction rate of 20% by the end of the 21st century.[203] According to Conservation International, "the country is one of the few nations that is, in its entirety, both a hotspot and a megadiversity country, placing it among the top priority hotspots for global conservation."[200]

Climate

The Philippines has a tropical maritime climate that is usually hot and humid. There are three seasons: tag-init or tag-araw, the hot dry season or summer from March to May; tag-ulan, the rainy season from June to November; and tag-lamig, the cool dry season from December to February. The southwest monsoon (from May to October) is known as the Habagat, and the dry winds of the northeast monsoon (from November to April), the Amihan.[204] Temperatures usually range from 21 °C (70 °F) to 32 °C (90 °F) although it can get cooler or hotter depending on the season. The coolest month is January; the warmest is May.[157][205]

The average yearly temperature is around 26.6 °C (79.9 °F).[204] In considering temperature, location in terms of latitude and longitude is not a significant factor. Whether in the extreme north, south, east, or west of the country, temperatures at sea level tend to be in the same range. Altitude usually has more of an impact. The average annual temperature of Baguio at an elevation of 1,500 meters (4,900 ft) above sea level is 18.3 °C (64.9 °F), making it a popular destination during hot summers.[204]

Sitting astride the typhoon belt, most of the islands experience annual torrential rains and thunderstorms from July to October,[206] with around nineteen typhoons entering the Philippine area of responsibility in a typical year and eight or nine making landfall.[207][208][209] Annual rainfall measures as much as 5,000 millimeters (200 in) in the mountainous east coast section but less than 1,000 millimeters (39 in) in some of the sheltered valleys.[206] The wettest known tropical cyclone to impact the archipelago was the July 1911 cyclone, which dropped over 1,168 millimeters (46.0 in) of rainfall within a 24-hour period in Baguio.[210] Bagyo is the local term for a tropical cyclone in the Philippines.[210] The Philippines is highly exposed to climate change and is among the world's ten countries that are most vulnerable to climate change risks.[211][212]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 7,500,000 | — |

| 1918 | 10,000,000 | +33.3% |

| 1939 | 16,000,000 | +60.0% |

| 1948 | 19,000,000 | +18.8% |

| 1960 | 27,087,685 | +42.6% |

| 1970 | 36,684,486 | +35.4% |

| 1975 | 42,070,660 | +14.7% |

| 1980 | 48,098,460 | +14.3% |

| 1990 | 60,703,206 | +26.2% |

| 1995 | 68,616,536 | +13.0% |

| 2000 | 76,506,928 | +11.5% |

| 2007 | 88,566,732 | +15.8% |

| 2010 | 92,337,852 | +4.3% |

| 2015 | 100,981,437 | +9.4% |

The Commission on Population estimated the country's population to be 107,190,081 as of December 31, 2018, based on the latest population census of 2015 conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority.[213] The population increased from 1990 to 2008 by approximately 28 million, a 45% growth in that time frame.[214] The first official census in the Philippines was carried out in 1877 and recorded a population of 5,567,685.[215]

It is estimated that half of the population resides on the island of Luzon. The 3.21% population growth rate between 1995 and 2000 decreased to an estimated 1.95% for the 2005–2010 period, but remains a contentious issue.[216][217] The population's median age is 22.7 years with 60.9% aged from 15 to 64 years old.[8] Life expectancy at birth is 69.4 years, 73.1 years for females and 65.9 years for males.[218] Poverty incidence also significantly dropped to 21.6% in 2015 from 25.2% in 2012.[219] Since the liberalization of United States immigration laws in 1965, the number of people in the United States having Filipino ancestry has grown substantially. In 2007 there were an estimated 12 million Filipinos living overseas.[220][221] [222]

Metro Manila is the most populous of the 3 defined metropolitan areas in the Philippines and the 8th most populous in the world in 2018. Census data from 2015 showed it had a population of 12,877,253 comprising almost 13% of the national population.[223] Including suburbs in the adjacent provinces (Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, and Rizal) of Greater Manila, the population is around 24,650,000.[223][224][225] Across the country, the Philippines has a total urbanization rate of 51.2 percent.[223] Metro Manila's gross regional product was estimated as of 2009[update] to be ₱468.4 billion (at constant 1985 prices) and accounts for 33% of the nation's GDP.[226] In 2011 Manila ranked as the 28th wealthiest urban agglomeration in the world and the 2nd in Southeast Asia.[227]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Quezon City  Manila |

1 | Quezon City | National Capital Region | 2,960,048 | 11 | Valenzuela | National Capital Region | 714,978 |  Davao City  Caloocan |

| 2 | Manila | National Capital Region | 1,846,513 | 12 | Dasmariñas | Calabarzon | 703,141 | ||

| 3 | Davao City | Davao Region | 1,776,949 | 13 | General Santos | Soccsksargen | 697,315 | ||

| 4 | Caloocan | National Capital Region | 1,661,584 | 14 | Parañaque | National Capital Region | 689,992 | ||

| 5 | Taguig | National Capital Region | 1,261,738 | 15 | Bacoor | Calabarzon | 664,625 | ||

| 6 | Zamboanga City | Zamboanga Peninsula | 977,234 | 16 | San Jose del Monte | Central Luzon | 651,813 | ||

| 7 | Cebu City | Central Visayas | 964,169 | 17 | Las Piñas | National Capital Region | 606,293 | ||

| 8 | Antipolo | Calabarzon | 887,399 | 18 | Bacolod | Negros Island Region | 600,783 | ||

| 9 | Pasig | National Capital Region | 803,159 | 19 | Muntinlupa | National Capital Region | 543,445 | ||

| 10 | Cagayan de Oro | Northern Mindanao | 728,402 | 20 | Calamba | Calabarzon | 539,671 | ||

Ethnic groups

According to the 2010 census, 24.4% of Filipinos are Tagalog, 11.4% Visayans/Bisaya (excluding Cebuano, Hiligaynon and Waray), 9.9% Cebuano, 8.8% Ilocano, 8.4% Hiligaynon, 6.8% Bikol, 4% Waray, and 26.2% as "others",[8][228] which can be broken down further to yield more distinct non-tribal groups like the Moro, the Kapampangan, the Pangasinense, the Ibanag, and the Ivatan.[229] There are also indigenous peoples like the Igorot, the Lumad, the Mangyan, the Bajau, and the tribes of Palawan.[230]

Filipinos generally belong to several Southeast Asian ethnic groups classified linguistically as part of the Austronesian or Malayo-Polynesian speaking people.[230] It is believed that thousands of years ago Austronesian-speaking Taiwanese aborigines migrated to the Philippines from Taiwan, bringing with them knowledge of agriculture and ocean-sailing, eventually displacing the earlier Negrito groups of the islands.[231] Negritos, such as the Aeta and the Ati, are considered among the earliest inhabitants of the islands.[232] These minority aboriginal settlers (Negritos) are an Australoid group and are a left-over from the first human migration out of Africa to Australia. However, the aboriginal people of the Philippines along with Papuans, Melanesians and Australian Aboriginals also hold sizable shared Denisovan admixture in their genomes.[233]

Being at the crossroads of the West and East, the Philippines is also home to migrants from places as diverse as China, Spain, Mexico, United States, India, South Korea, and Japan. The Chinese are mostly the descendants of immigrants from Fujian in China after 1898, numbering around 2 million, although there are an estimated 27 percent of Filipinos who have partial Chinese ancestry,[234][235] stemming from precolonial and colonial Chinese migrants.[236]

Furthermore, at least one-third of the population of Luzon, where Spaniards mixed with natives, as well as old settlements in the Visayas (founded by Mexicans)[237] and Zamboanga City (colonized by Peruvians)[238] or around 13.33% of the Philippine population, have partial Hispanic ancestry (from varying points of origin and ranging from Ibero-America[239] to Spain).[240] Recent genetic studies confirm this partial European[241] and Hispanic-American ancestry.[242] The migrants from Peru and Mexico were not even homogeneous since they themselves were already racially admixed Mestizos or Mulattos[78] but there were also a few Native-Americans too.[243]

As of 2015, there were 220,000 to 600,000 American citizens living in the country.[244] There are also 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of Angeles, Manila, Clark and Olongapo.[245] Other important non-indigenous minorities include Arabs. There are also Japanese people, mostly escaped Christians (Kirishitan) who fled the persecutions of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu which the Spanish empire in the Philippines had offered asylum from. The descendants of mixed-race couples are known as Tisoy.[246][247]

Languages

| Language | Speakers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | 24.44 % | 22,512,089 | |

| Cebuano | 21.35 % | 19,665,453 | |

| Ilokano | 8.77 % | 8,074,536 | |

| Hiligaynon | 8.44 % | 7,773,655 | |

| Waray | 3.97 % | 3,660,645 | |

| Other local languages/dialects | 26.09 % | 24,027,005 | |

| Other foreign languages/dialects | 0.09 % | 78,862 | |

| Not reported/not stated | 0.01 % | 6,450 | |

| TOTAL | 92,097,978 | ||

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[248] | |||

Ethnologue lists 186 individual languages in the Philippines, 182 of which are living languages, while 4 no longer have any known speakers. Most native languages are part of the Philippine branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, which is itself a branch of the Austronesian language family.[230] In addition, various Spanish-based creole varieties collectively called Chavacano exist.[249] There are also many Philippine Negrito languages that have unique vocabularies that survived Austronesian acculturation.[250]

Filipino and English are the official languages of the country.[251] Filipino is a standardized version of Tagalog, spoken mainly in Metro Manila and other urban regions. Both Filipino and English are used in government, education, print, broadcast media, and business. Due to the Philippines' history of complex interactions with cultures across the world, the Filipino language has a rich repertoire of incorporated foreign vocabulary used in everyday speech. Filipino has borrowings from, among other languages, English, Latin, Greek, Spanish,[252] Arabic,[253] Persian, Sanskrit,[254] Malay,[255] Chinese,[256][257] Japanese,[258] and Nahuatl.[259] Furthermore, in most towns, the local indigenous language are also spoken. The Philippine constitution provides for the promotion of Spanish and Arabic on a voluntary and optional basis,[251] although neither are used on as wide a scale as in the past. Spanish, which was widely used as a lingua franca in the late nineteenth century, has since declined greatly in use, although Spanish loanwords are still present today in many of the indigenous Philippine languages,[260] while Arabic is mainly used in Islamic schools in Mindanao.[261] A theory that the indigenous scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines are descended from an early form of the Gujarati script was presented at the 2010 meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.[262]

Nineteen regional languages act as auxiliary official languages used as media of instruction: Aklanon, Bikol, Cebuano, Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ibanag, Ilocano, Ivatan, Kapampangan, Kinaray-a, Maguindanao, Maranao, Pangasinan, Sambal, Surigaonon, Tagalog, Tausug, Waray, and Yakan.[2] Other indigenous languages such as, Cuyonon, Ifugao, Itbayat, Kalinga, Kamayo, Kankanaey, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Manobo, and several Visayan languages are prevalent in their respective provinces.[263] Article 3 of Republic Act No. 11106 declared the Filipino Sign Language as the national sign language of the Philippines, specifying that it shall be recognized, supported and promoted as the medium of official communication in all transactions involving the deaf, and as the language of instruction of deaf education.[264][265]

Languages not indigenous to the islands are also taught in select schools. Mandarin is taught in Chinese schools catering to the Chinese Filipino community. Islamic schools in Mindanao teach Modern Standard Arabic in their curriculum.[266] French, German, Japanese, Hindi, Korean, and Spanish are taught with the help of foreign linguistic institutions.[267] The Department of Education began teaching the Malay languages of Indonesian and Malaysian in 2013.[268]

Religion

Religion in the Philippines, 2010 estimate by CIA[269]

The Philippines is an officially secular state, although Christianity is the dominant faith.[270] Census data from 2010 found that about 80.58% of the population professed Catholicism.[5] Around 37% regularly attend Mass and 29% identify as very religious.[271][272] The Philippine Independent Church is a notable independent Catholic denomination.[273][274][275]

Protestants were 10.8%[276] of the total population, mostly endorsing evangelical Protestant denominations that were introduced by American missionaries at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, they are heavily concentrated in Northern Luzon and Southern Mindanao.[277][278] Iglesia ni Cristo is a notable Unitarian and Restorationist denomination in the Philippines and is mostly concentrated in Central Luzon.[279][280]

Islam is the second largest religion. The Muslim population of the Philippines was reported as 5.57% of the total population according to census returns in 2010.[5] Conversely, a 2012 report by the National Commission of Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) stated that about 10,700,000 or 11%[281] of the Filipinos are Muslims. Some Muslim scholars argue that the census taken in 2000 significantly undercounted the number of Muslims because of security concerns and hostility of the inhabitants to government personnel in Muslim-majority areas, leading to difficulty in getting accurate data for the Muslim population in the country.[282][283] The majority of Muslims live in Mindanao and nearby islands.[284][285][286][287][288] Most practice Sunni Islam under the Shafi'i school.[289][290]

The percentage of non-religious people in the Philippines was measured to be about 11% of the population in a 2006 survey by Dentsu Research Institute, while a 2014 survey by Gallup International Association measured it as 21%.[291][292] The Philippine Atheists and Agnostics Society (PATAS) is a nonprofit organization for the public understanding of atheism and agnosticism in the Philippines which educates society, and eliminates myths and misconceptions about atheism and agnosticism.[293] The 2010 Philippine Census reported the religion of about 0.08% of the population as "none".[5]

Buddhism is practiced by around 2% of the population, concentrated among Filipinos of Chinese descent.[280][289][294] An estimated 2% of the total population practice Philippine traditional religions, whose practices and folk beliefs are often syncretized with Christianity and Islam.[280][294] The remaining population is divided between a number of religious groups, including Hindus, Jews, and Baha'is.[295]

Government and politics

The Philippines has a democratic government in the form of a constitutional republic with a presidential system.[296] It is governed as a unitary state with the exception of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), which is largely free from the national government. There have been attempts to change the government to a federal, unicameral, or parliamentary government since the Ramos administration.[297][298]

The President functions as both head of state and head of government and is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president is elected by popular vote for a single six-year term, during which he or she appoints and presides over the cabinet.[157] The bicameral Congress is composed of the Senate, serving as the upper house, with members elected to a six-year term, and the House of Representatives, serving as the lower house, with members elected to a three-year term.[157]

Senators are elected at large while the representatives are elected from both legislative districts and through sectoral representation.[157] The judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court, composed of a Chief Justice as its presiding officer and fourteen associate justices, all of whom are appointed by the President from nominations submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council.[157]

Foreign relations

The Philippines' international relations are based on trade with other nations and the well-being of the 10 million overseas Filipinos living outside the country.[299] As a founding and active member of the United Nations, the Philippines has been elected several times into the Security Council. Carlos P. Romulo was a former President of the United Nations General Assembly. The country is an active participant in the Human Rights Council as well as in peacekeeping missions, particularly in East Timor.[300][301][302]

The Philippines is a founding and active member of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), an organization designed to strengthen relations and promote economic and cultural growth among states in the Southeast Asian region.[303] It has hosted several summits and is an active contributor to the direction and policies of the bloc.[304] It is also a member of the East Asia Summit (EAS), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Latin Union, the Group of 24, and the Non-Aligned Movement.[157] The country is also seeking to strengthen relations with Islamic countries by campaigning for observer status in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[305][306]

The Philippines attaches great importance in its relations with China, and has established significant cooperation with the country.[307][308][309][310][311][312] It supported the United States during the Cold War and the War on Terror and was a major non-NATO ally, before the major fallback of relationship between the Philippines and United States in favor of China and Russia.[313] In addition, controversies related to the presence of the now former U.S. military bases in Subic Bay and Clark and the current Visiting Forces Agreement have flared up from time to time.[299][failed verification] Japan, the biggest contributor of official development assistance to the country,[314] is thought of as a friend. Although historical tensions still exist on issues such as the plight of comfort women, much of the animosity inspired by memories of World War II has faded.[315]

Relations with other nations are generally positive. Shared democratic values ease relations with Western and European countries while similar economic concerns help in relations with other developing countries. Historical ties and cultural similarities also serve as a bridge in relations with Spain.[316][317][318] Despite issues such as domestic abuse and war affecting overseas Filipino workers,[319][320] relations with Middle Eastern countries are friendly as seen in the continuous employment of more than two million overseas Filipinos living there.[321]

The Philippines has an ongoing territorial dispute with Spratly Islands with China, Taiwan, Malaysia and Vietnam. The country Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012 deteriorated the country's relation with China, when the shoal was grabbed by the Chinese which has been in Philippine possession until the standoff. Issues involving Taiwan, the Spratly Islands, and concerns of expanding Chinese influence are taken with a degree of caution. Foreign policy has been mostly about economic relations with its Southeast Asian and Asia-Pacific neighbors.

Military

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) are responsible for national security and consist of three branches: the Philippine Air Force, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Navy (includes the Marine Corps).[322][323][324] The Armed Forces of the Philippines are a volunteer force.[325] Civilian security is handled by the Philippine National Police under the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG).[326][327]

In the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, the largest separatist organization, the Moro National Liberation Front, is now engaging the government politically. Other more militant groups like the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the communist New People's Army, and the Abu Sayyaf have previously kidnapped foreigners for ransom, particularly on the southern island of Mindanao.[329][330][331][332] Their presence decreased due to successful security provided by the Philippine government.[333][334] At 1.1 percent of GDP, the Philippines spent less on its military forces than the regional average. As of 2014[update] Malaysia and Thailand were estimated to spend 1.5%, China 2.1%, Vietnam 2.2% and South Korea 2.6%.[335][336]