Calgary: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the Canadian city|other uses|Calgary (disambiguation)}} |

{{About|the Canadian city|other uses|Calgary (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{refimprove|date=March 2016}} |

|||

{{Use Canadian English|date=March 2015}} |

{{Use Canadian English|date=March 2015}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2017}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2017}} |

||

Revision as of 20:19, 17 February 2018

Calgary | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Calgary | |

| |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Onward | |

| Coordinates: 51°03′N 114°04′W / 51.050°N 114.067°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Region | Calgary Region |

| Census division | 6 |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Incorporated[5] | |

| • Town | November 7, 1884 |

| • City | January 1, 1894 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Naheed Nenshi |

| • Governing body |

|

| • Manager | Jeff Fielding[6] |

| • MPs | List of MPs |

| • MLAs | List of MLAs |

| Area | |

| • Land | 825.56 km2 (318.75 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 586.08 km2 (226.29 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,110.21 km2 (1,973.06 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,045 m (3,428 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 1,239,220 |

| • Density | 1,501.1/km2 (3,888/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,237,656 |

| • Urban density | 2,111.8/km2 (5,470/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,392,609 (4th) |

| • Metro density | 272.5/km2 (706/sq mi) |

| • Municipal census (2017) | 1,246,337[11] |

| Demonym | Calgarian |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Forward sortation areas | |

| Area code(s) | 403, 587, 825 |

| Highways | 1, 1A, 2, 2A, 8, 22X, 201 |

| Waterways | Bow River, Elbow River, Glenmore Reservoir |

| GDP | US$ 97.9 billion[12] |

| GDP per capita | US$ 69,826[12] |

| Website | Official website |

Calgary (/ˈkælɡəri, -ɡri/ ) is a city in the Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated at the confluence of the Bow River and the Elbow River in the south of the province, in an area of foothills and prairie, about 80 km (50 mi) east of the front ranges of the Canadian Rockies. The city anchors the south end of what Statistics Canada defines as the "Calgary–Edmonton Corridor".[13]

The city had a population of 1,239,220 in 2016, making it Alberta's largest city and Canada's third-largest municipality.[7] Also in 2016, Calgary had a metropolitan population of 1,392,609, making it the fourth-largest census metropolitan area (CMA) in Canada.[9]

The economy of Calgary includes activity in the energy, financial services, film and television, transportation and logistics, technology, manufacturing, aerospace, health and wellness, retail, and tourism sectors.[14] The Calgary CMA is home to the second-highest number of corporate head offices in Canada among the country's 800 largest corporations.[15] As a result of its strong performing economy, especially during periods of oil boom, Calgary holds many economic distinctions particularly in categories related to personal wealth. In 2015, Calgary had the highest number of millionaires per capita of any major city in Canada.[16]

In 1988, Calgary became the first Canadian city to host the Winter Olympic Games. Calgary has been consistently recognized for its high quality of life. Economist Intelligence Unit analysts have ranked Calgary as the 5th most livable city in the world in 2017 for the 8th consecutive year.[17]

Etymology

Calgary was named after Calgary on the Isle of Mull, Scotland.[18] In turn, the name originates from a compound of kald and gart, similar Old Norse words, meaning "cold" and "garden", likely used when named by the Vikings who inhabited the Inner Hebrides.[19] Alternatively, the name might be Gaelic Cala ghearraidh, meaning "beach of the meadow (pasture)"; or Gaelic for either "clear running water" or "bay farm".[18]

Prior to contact, the indigenous peoples of Southern Alberta referred to the Calgary area as "elbow," in reference to the sharp bend made by the Bow River and the Elbow River. In some cases, the area was named after the reeds that grew along the riverbanks, which were used to fashion bows. In the Blackfoot language (Siksiká), the area was known as Mohkínstsis akápiyoyis, meaning "elbow many houses," reflecting its strong settler presence. The shorter form of the Blackfoot name, Mohkínstsis, simply meaning "elbow."[20][21][22], has been the popular "indigenous" term for the Calgary area.[23][24][25][26][27] In the Stoney language (Nakoda), the area was known as Wincheesh-pah or Wenchi Ispase, both meaning "elbow."[20][22] In the Cree Language, the area was known as Otoskwanik meaning "house at the elbow" or Otoskwunee meaning "elbow." In the Sarcee language (Tsuut’ina), the area was known as Kootsisáw meaning "elbow."[20][22] In the Slavey language, the area was known as Klincho-tinay-indihay meaning "many horse town," referring to the Calgary Stampede[20] and the city's settler heritage.[22]

There have been several attempts to revive the indigenous names of Calgary. In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, local post-secondary institutions have adopted 'official acknowledgements' of indigenous territory using the Blackfoot name of the City, Mohkínstsis.[25][26][28][29][30] In 2017, the Stoney Nakoda sent an application to the Government of Alberta, to rename Calgary as Wichispa Oyade meaning "elbow town,"[31] however this has been challenged by the Piikani Blackfoot.[32]

History

First settlement

The Calgary area was inhabited by pre-Clovis people whose presence has been traced back at least 11,000 years.[33] Before the arrival of Europeans, the area was inhabited by the Blackfoot, Blood, Peigan and the Tsuu T'ina First Nations peoples, all of which were part of the Blackfoot Confederacy.[citation needed] In 1787, cartographer David Thompson spent the winter with a band of Peigan encamped along the Bow River. He was a Hudson's Bay Company trader and the first recorded European to visit the area. John Glenn was the first documented European settler in the Calgary area, in 1873.[34]

In 1875, the site became a post of the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or RCMP). The NWMP detachment was assigned to protect the western plains from US whisky traders, and to protect the fur trade. Originally named Fort Brisebois, after NWMP officer Éphrem-A. Brisebois, it was renamed Fort Calgary in 1876 by Colonel James Macleod.

When the Canadian Pacific Railway reached the area in 1883, and a rail station was constructed, Calgary began to grow into an important commercial and agricultural centre. Over a century later, the Canadian Pacific Railway headquarters moved to Calgary from Montreal in 1996.[35] Calgary was officially incorporated as a town in 1884, and elected its first mayor, George Murdoch. In 1894, it was incorporated as "The City of Calgary" in what was then the North-West Territories.[36] The Calgary Police Service was established in 1885 and assumed municipal, local duties from the NWMP.[37]

The Calgary Fire of 1886 occurred on November 7, 1886. Fourteen buildings were destroyed with losses estimated at $103,200. Although no one was killed or injured,[38] city officials drafted a law requiring all large downtown buildings to be built with Paskapoo sandstone, to prevent this from happening again.[39]

After the arrival of the railway, the Dominion Government started leasing grazing land at minimal cost (up to 100,000 acres (400 km2) for one cent per acre per year). As a result of this policy, large ranching operations were established in the outlying country near Calgary. Already a transportation and distribution hub, Calgary quickly became the centre of Canada's cattle marketing and meatpacking industries.[citation needed]

By the late 19th century, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) expanded into the interior and established posts along rivers that later developed into the modern cities of Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton. In 1884, the HBC established a sales shop in Calgary. The HBC also built the first of the grand "original six" department stores in Calgary in 1913, the others that followed are Edmonton, Vancouver, Victoria, Saskatoon, and Winnipeg.[40][41]

Between 1896 and 1914 settlers from all over the world poured into the area in response to the offer of free "homestead" land.[42] Agriculture and ranching became key components of the local economy, shaping the future of Calgary for years to come.[citation needed] The world-famous Calgary Stampede, still held annually in July, was started by four wealthy ranchers as a small agricultural show in 1912.[43] It is now known as the "greatest outdoor show on earth".[44]

Oil boom

Oil was first discovered in Alberta in 1902,[45] but it did not become a significant industry in the province until 1947 when reserves of it were discovered near Leduc. Calgary quickly found itself at the centre of the ensuing oil boom. The city's economy grew when oil prices increased with the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973. The population increased by 272,000 in the eighteen years between 1971 (403,000) and 1989 (675,000) and another 345,000 in the next eighteen years (to 1,020,000 in 2007). During these boom years, skyscrapers were constructed and the relatively low-rise downtown quickly became dense with tall buildings.[46]

Calgary's economy was so closely tied to the oil industry that the city's boom peaked with the average annual price of oil in 1981.[47] The subsequent drops in oil prices were cited by industry as reasons for a collapse in the oil industry and consequently the overall Calgary economy. Low oil prices prevented a full recovery until the 1990s.[48]

Recent history

With the energy sector employing a huge number of Calgarians, the fallout from the economic slump of the early 1980s was significant, and the unemployment rate soared.[49] By the end of the decade, however, the economy was in recovery. Calgary quickly realized that it could not afford to put so much emphasis on oil and gas, and the city has since become much more diverse, both economically and culturally. The period during this recession marked Calgary's transition from a mid-sized and relatively nondescript prairie city into a major cosmopolitan and diverse centre. This transition culminated in the city hosting Canada's first Winter Olympics in 1988.[50] The success of these Games[51] essentially put the city on the world stage.

Thanks in part to escalating oil prices, the economy in Calgary and Alberta was booming until the end of 2009, and the region of nearly 1.1 million people was home to the fastest growing economy in the country.[52] While the oil and gas industry comprise an important part of the economy, the city has invested a great deal into other areas such as tourism and high-tech manufacturing. Over 3.1 million people now visit the city annually[53] for its many festivals and attractions, especially the Calgary Stampede. The nearby mountain resort towns of Banff, Lake Louise, and Canmore are also becoming increasingly popular with tourists, and are bringing people into Calgary as a result. Other modern industries include light manufacturing, high-tech, film, e-commerce, transportation, and services.

Widespread flooding throughout southern Alberta, including on the Bow and Elbow rivers, forced the evacuation of over 75,000 city residents on June 21, 2013, and left large areas of the city, including downtown, without power.[54][55]

Geography

Calgary is located at the transition zone between the Canadian Rockies foothills and the Canadian Prairies. The city lies within the foothills of the Parkland Natural Region and the Grasslands Natural Region.[56] Downtown Calgary is about 1,042.4 m (3,420 ft) above sea level,[10] and the airport is 1,076 m (3,531 ft).[57] In 2011, the city covered a land area of 825.29 km2 (318.65 sq mi).[58]

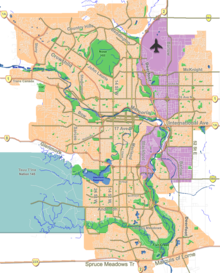

Two rivers run through the city. The Bow River is the larger and it flows from the west to the south. The Elbow River flows northwards from the south until it converges with the Bow River at the historic site of Fort Calgary near downtown. Since the climate of the region is generally dry, dense vegetation occurs naturally only in the river valleys, on some north-facing slopes, and within Fish Creek Provincial Park.[citation needed]

The City of Calgary, 848 km2 (327 sq mi) in size,[59] consists of an inner city surrounded by suburban communities of various density.[60] The city is immediately surrounded by two municipal districts – the Municipal District of Foothills No. 31 to the south and Rocky View County to the north, west and east. Proximate urban communities beyond the city within the Calgary Region include: the City of Airdrie to the north; the City of Chestermere, the Town of Strathmore and the Hamlet of Langdon to the east; the towns of Okotoks and High River to the south; and the Town of Cochrane to the northwest.[61] Numerous rural subdivisions are located within the Elbow Valley, Springbank and Bearspaw areas to the west and northwest.[62][63][64] The Tsuu T'ina Nation Indian Reserve No. 145 borders Calgary to the southwest.[61]

Over the years, the city has made many land annexations to facilitate growth. In the most recent annexation of lands from Rocky View County, completed in July 2007, the city annexed Shepard, a former hamlet, and placed its boundaries adjacent to the Hamlet of Balzac and City of Chestermere, and very close to the City of Airdrie.[65]

Flora and fauna

Numerous plant and animal species are found within and around Calgary. The Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca) comes near the northern limit of its range at Calgary.[66] Another conifer of widespread distribution found in the Calgary area is the White Spruce (Picea glauca).[citation needed]

Neighbourhoods

The downtown region of the city consists of five neighbourhoods: Eau Claire (including the Festival District), the Downtown West End, the Downtown Commercial Core, Chinatown, and the Downtown East Village (also part of the Rivers District). The commercial core is itself divided into a number of districts including the Stephen Avenue Retail Core, the Entertainment District, the Arts District and the Government District. Distinct from downtown and south of 9th Avenue is Calgary's densest neighbourhood, the Beltline. The area includes a number of communities such as Connaught, Victoria Crossing and a portion of the Rivers District. The Beltline is the focus of major planning and rejuvenation initiatives on the part of the municipal government[67] to increase the density and liveliness of Calgary's centre.[citation needed]

Adjacent to, or directly radiating from the downtown are the first of the inner-city communities. These include Crescent Heights, Hounsfield Heights/Briar Hill, Hillhurst/Sunnyside (including Kensington BRZ), Bridgeland, Renfrew, Mount Royal, Scarboro, Sunalta, Mission, Ramsay and Inglewood and Albert Park/Radisson Heights directly to the east. The inner city is, in turn, surrounded by relatively dense and established neighbourhoods such as Rosedale and Mount Pleasant to the north; Bowness, Parkdale and Glendale to the west; Park Hill, South Calgary (including Marda Loop), Bankview, Altadore, and Killarney to the south; and Forest Lawn/International Avenue to the east. Lying beyond these, and usually separated from one another by highways, are suburban communities including Evergreen, Somerset,Auburn Bay Country Hills, Sundance, Riverbend, and McKenzie Towne. In all, there are over 180 distinct neighbourhoods within the city limits.[68]

Several of Calgary's neighbourhoods were initially separate municipalities that were annexed by the city as it grew. These include Bowness, Montgomery, and Forest Lawn.

Climate

| Calgary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Calgary experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb). It falls into the NRC Plant Hardiness Zone 4a.[70] According to Environment Canada, average daily temperatures in Calgary range from 16.5 °C (61.7 °F) in July to −6.8 °C (19.8 °F) in December.[69]

Winters are cold and the air temperature can drop to or below −20 °C (−4 °F) on average of 22 days of the year and −30 °C (−22 °F) on average of 3.7 days of the year, and are often broken up by warm, dry Chinook winds that blow into Alberta over the mountains. These winds can raise the winter temperature by 20 °C (36 °F), and as much as 30 °C (54 °F) in just a few hours, and may last several days.[71] As well, Calgary's proximity to the Rocky Mountains affects winter temperature average mean temperature with a mixture of lows and highs, and tends to result in a mild winter for a city in the Prairie Provinces. Temperatures are also affected by the wind chill factor, Calgary's average wind speed is 14.2 km/h, one of the highest in Canadian cities.[72]

In summer, daytime temperatures can exceed 30 °C (86 °F) an average of 5.1 days anytime in June, July and August, and occasionally as late as September or as early as May, and in winter drop below or at −30 °C (−22 °F) 3.7 days of the year. As a consequence of Calgary's high elevation and aridity, summer evenings tend to cool off, with monthly averages below 10 °C (50 °F) throughout the summer months.[69]

Calgary has the most sunny days year round of Canada's 100 largest cities, with just over 332 days of sun;[69] it has on average 2,396 hours of sunshine annually.[69] With an average relative humidity of 55% in the winter and 45% in the summer (15:00 MST),[69]

Calgary International Airport in the northeastern section of the city receives an average of 418.8 mm (16.49 in) of precipitation annually, with 326.4 mm (12.85 in) of that occurring in the form of rain, and 129 cm (51 in) as snow.[69] The most rainfall occurs in June and the most snowfall in March.[69] Calgary has also recorded snow every month of the year.[73] It is uncommon in July, but not unheard of. The last notable event was on July 15, 1999.[74][75]

Thunderstorms can be frequent and some times severe[76] with most of them occurring in the summer months. Calgary lies within Alberta's Hailstorm Alley and is prone to damaging hailstorms every few years. A hailstorm that struck Calgary on September 7, 1991, was one of the most destructive natural disasters in Canadian history, with over $400 million in damage.[77] Being west of the dry line on most occasions, tornadoes are rare in the region.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Calgary was 36.1 °C (97 °F) on July 15, 1919, and July 25, 1933.[69][78] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −45.0 °C (−49 °F) on February 4, 1893.[69]

| Climate data for Calgary International Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1881–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 17.3 | 21.9 | 25.2 | 27.2 | 31.6 | 33.3 | 36.9 | 36.0 | 32.9 | 28.7 | 22.2 | 19.4 | 36.9 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −7.1 (19.2) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −13.2 (8.2) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −44.4 (−47.9) |

−45.0 (−49.0) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−35.0 (−31.0) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

−45.0 (−49.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −52.1 | −52.6 | −44.7 | −37.1 | −23.7 | −5.8 | 0.0 | −4.1 | −12.5 | −34.3 | −47.9 | −55.1 | −55.1 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.4 (0.37) |

9.4 (0.37) |

17.8 (0.70) |

25.2 (0.99) |

56.8 (2.24) |

94.0 (3.70) |

65.5 (2.58) |

57.0 (2.24) |

45.1 (1.78) |

15.3 (0.60) |

13.1 (0.52) |

10.2 (0.40) |

418.8 (16.49) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

2.2 (0.09) |

10.8 (0.43) |

46.1 (1.81) |

93.9 (3.70) |

65.5 (2.58) |

57.0 (2.24) |

41.7 (1.64) |

7.5 (0.30) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.3 (0.01) |

326.4 (12.85) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.3 (6.0) |

14.5 (5.7) |

22.7 (8.9) |

18.8 (7.4) |

11.9 (4.7) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.9 (1.5) |

10.0 (3.9) |

16.6 (6.5) |

15.0 (5.9) |

128.8 (50.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.3 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 11.2 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 10.6 | 9.1 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 111.8 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.27 | 0.20 | 1.3 | 4.1 | 10.1 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 10.5 | 8.7 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 0.40 | 67.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.7 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.10 | 1.3 | 4.1 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 54.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 54.5 | 53.2 | 50.3 | 40.7 | 43.5 | 48.6 | 46.8 | 44.6 | 44.3 | 44.3 | 54.0 | 55.3 | 48.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.5 | 144.6 | 177.2 | 220.2 | 249.4 | 269.9 | 314.1 | 284.0 | 207.0 | 175.4 | 121.1 | 114.0 | 2,396.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 45.6 | 51.3 | 48.2 | 53.1 | 51.8 | 54.6 | 63.1 | 62.9 | 54.4 | 52.7 | 45.0 | 46.0 | 52.4 |

| Source: Environment Canada[69] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for University of Calgary, 1971–2000 normals, extremes 1964–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

4.3 (39.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −13.5 (7.7) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −40.6 (−41.1) |

−38.0 (−36.4) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−34.0 (−29.2) |

−41.1 (−42.0) |

−41.1 (−42.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.5 (0.69) |

13.9 (0.55) |

18.7 (0.74) |

29.1 (1.15) |

64.0 (2.52) |

64.4 (2.54) |

66.8 (2.63) |

60.2 (2.37) |

51.8 (2.04) |

14.8 (0.58) |

13.2 (0.52) |

16.5 (0.65) |

430.9 (16.98) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.2 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.6 (0.06) |

13.3 (0.52) |

54.9 (2.16) |

64.4 (2.54) |

66.8 (2.63) |

60.2 (2.37) |

47.1 (1.85) |

5.0 (0.20) |

0.6 (0.02) |

0.2 (0.01) |

314.4 (12.37) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 17.3 (6.8) |

13.8 (5.4) |

17.1 (6.7) |

15.8 (6.2) |

9.1 (3.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

4.7 (1.9) |

9.7 (3.8) |

12.6 (5.0) |

16.4 (6.5) |

116.5 (45.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 9.1 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 110.8 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 3.7 | 10.5 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 3.0 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 65 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9.1 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 51.3 |

| Source: Environment Canada | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 3,876 | — |

| 1901 | 4,091 | +5.5% |

| 1906 | 11,967 | +192.5% |

| 1911 | 43,704 | +265.2% |

| 1916 | 56,514 | +29.3% |

| 1921 | 63,305 | +12.0% |

| 1926 | 65,291 | +3.1% |

| 1931 | 83,761 | +28.3% |

| 1936 | 83,407 | −0.4% |

| 1941 | 88,904 | +6.6% |

| 1946 | 100,044 | +12.5% |

| 1951 | 129,060 | +29.0% |

| 1956 | 181,780 | +40.8% |

| 1961 | 249,641 | +37.3% |

| 1966 | 330,575 | +32.4% |

| 1971 | 403,319 | +22.0% |

| 1976 | 469,917 | +16.5% |

| 1981 | 592,743 | +26.1% |

| 1986 | 636,107 | +7.3% |

| 1991 | 710,795 | +11.7% |

| 1996 | 768,082 | +8.1% |

| 2001 | 878,866 | +14.4% |

| 2006 | 988,193 | +12.4% |

| 2011 | 1,096,833 | +11.0% |

| 2016 | 1,239,220 | +13.0% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89] [58][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][7] | ||

The population of the City of Calgary according to its 2017 municipal census is 1,246,337,[100] a change of 0.9% from its 2016 municipal census population of 1,235,171.[101]

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Calgary recorded a population of 1,239,220 living in 466,725 of its 489,650 total private dwellings, a change of 13% from its 2011 population of 1,096,833. With a land area of 825.56 km2 (318.75 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,501.1/km2 (3,887.7/sq mi) in 2016.[7] Calgary was ranked 1st among the three cities in Canada that saw their population grow by more than 100,000 people between 2011 and 2016. During this time Calgary saw a population growth of 142,387 people, followed by Edmonton at 120,345 people and Toronto at 116,511 people.[102]

In the 2011 Census, the City of Calgary had a population of 1,096,833 living in 423,417 of its 445,848 total dwellings, a change of 10.9% from its 2006 adjusted population of 988,812. With a land area of 825.29 km2 (318.65 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,329.0/km2 (3,442.2/sq mi) in 2011.[58] According to the 2011 Statistics Canada Census, persons aged 14 years and under made up 17.9% of the population, and those aged 65 and older made up 9.95%. The median age was 36.4 years. In 2011, the city's gender population was 49.9% male and 50.1% female.[103]

The Calgary census metropolitan area (CMA) is the fifth-largest CMA in Canada and largest in Alberta. It had a population of 1,214,839 in the 2011 Census compared to its 2006 population of 1,079,310. Its five-year population change of 12.6 percent was the highest among all CMAs in Canada between 2006 and 2011. With a land area of 5,107.55 km2 (1,972.04 sq mi), the Calgary CMA had a population density of 237.9/km2 (616.0/sq mi) in 2011.[104] Statistics Canada's latest estimate of the Calgary CMA population, as of July 1, 2013, is 1,364,827.[105] The population within an hour commuting distance of the city is 1,511,755.[106]

As a consequence of the large number of corporations, as well as the presence of the energy sector in Alberta, Calgary has a median family income of $104,530.[107]

Ethnicity

As of 2016, 36.2% of the population belong to a visible minority group. Of the largest Canadian cities, Calgary ranked fourth in proportion of visible minorities, behind Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg. Among the immigrants arriving in Calgary between 2001 and 2006, 78% belonged to a visible minority group. South Asians (mainly from India or Pakistan) make up the largest group (7.5%), followed by Chinese (6.8%). There were more than 200 different ethnic origins in Calgary, the most frequently reported were English, Scottish, Canadian, German and Irish.[108]

Religions

Christians make up 54.9% of the population, while 32.3% have no religious affiliation. Other religions in the city are Muslims (5.2%), Sikhs (2.6%) and Buddhists (2.1%).[109]

Its St. Mary’s Cathedral is the see of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Calgary. There is also an Anglican Diocese of Calgary.

Economy

Calgary is recognized as a Canadian leader in the oil and gas industry as well as for being a leader in economic expansion.[110] Its high personal and family incomes,[15][111] low unemployment and high GDP per capita[112] have all benefited from increased sales and prices due to a resource boom,[110] and increasing economic diversification.

Calgary benefits from a relatively strong job market in Alberta, is part of the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor, one of the fastest growing regions in the country. It is the head office for many major oil and gas related companies, and many financial service business have grown up around them. Small business and self-employment levels also rank amongst the highest in Canada.[111] It is also a distribution and transportation hub[113] with high retail sales.[111]

Calgary's economy is decreasingly dominated by the oil and gas industry, although it is still the single largest contributor to the city's GDP. In 2006, Calgary's real GDP (in constant 1997 dollars) was C$52.386 billion, of which oil, gas and mining contributed 12%.[114] The larger oil and gas companies are BP Canada, Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Cenovus Energy, Encana, Imperial Oil, Suncor Energy, Shell Canada, Husky Energy, TransCanada, and Nexen, making the city home to 87% of Canada's oil and natural gas producers and 66% of coal producers.[115]

| Labour force (2016)[116] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Calgary | Alberta | Canada |

| Employment | 66.9% | 66.3% | 61.2% |

| Unemployment | 10.3% | 9.0% | 6.8% |

| Participation | 74.6% | 72.9% | 65.6% |

As of November 2016, the city had a labour force of 901,700 (a 74.6% participation rate) and 10.3% unemployment rate.[117][118][119] In 2006, the unemployment rate was amongst the lowest of the major cities in Canada at 3.2%,[120] causing a shortage of both skilled and unskilled workers.[121]

| Employment by industry[122] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry | Calgary | Alberta |

| Agriculture | 6.1% | 10.9% |

| Manufacturing | 15.8% | 15.8% |

| Trade | 15.9% | 15.8% |

| Finance | 6.4% | 5.0% |

| Health and education | 25.1% | 18.8% |

| Business services | 25.1% | 18.8% |

| Other services | 16.5% | 18.7% |

In 2010 the "Professional, Technical and Management" Industry accounted for over 14% of employment and the areas of "Architectural, Engineering and Design Services" and "Management, Scientific and Technical Services" employment levels far exceed Canadian levels. Though Trade employs 14.7% of the work force, its percentage of total employment is not higher than the Canadian average. Levels of employment in Construction are both fairly high, exceed Canadian averages, and have grown 16% between 2006 and 2010. Health and Welfare services, which account for 10% of employment, have grown 20% in that period.[110][123]

In 2006, the top three private sector employers in Calgary were Shaw Communications (7,500 employees), Nova Chemicals (4,945) and Telus (4,517).[124] Companies rounding out the top ten were Mark's Work Wearhouse, the Calgary Co-op, Nexen, Canadian Pacific Railway, CNRL, Shell Canada and Dow Chemical Canada.[124] The top public sector employers in 2006 were the Calgary Zone of the Alberta Health Services (22,000), the City of Calgary (12,296) and the Calgary Board of Education (8,000).[124] Public sector employers rounding out the top five were the University of Calgary and the Calgary Roman Catholic Separate School Division.[124]

In Canada, Calgary has the second-highest concentration of head offices in Canada (behind Toronto), the most head offices per capita, and the highest head office revenue per capita.[15][111] Some large employers with Calgary head offices include Canada Safeway Limited, Westfair Foods Ltd., Suncor Energy, Agrium, Flint Energy Services Ltd., Shaw Communication, and Canadian Pacific Railway.[125] CPR moved its head office from Montreal in 1996 and Imperial Oil moved from Toronto in 2005. EnCana's new 58-floor corporate headquarters, the Bow, became the tallest building in Canada outside of Toronto.[126] In 2001, the city became the corporate headquarters of the TSX Venture Exchange.

WestJet is headquartered close to the Calgary International Airport,[127] and Enerjet has its headquarters on the airport grounds.[128] Prior to their dissolution, Canadian Airlines[129] and Air Canada's subsidiary Zip were also headquartered near the city's airport.[130] Although the main office is now based in Yellowknife, Canadian North, purchased from Canadian Airlines in September 1998, still maintain the operations and charter offices in Calgary.[131][132]

According to a report by Alexi Olcheski of Avison Young published in August 2015, vacancy rates rose to 11.5 per cent in the second quarter of 2015 from 8.3 per cent in 2014. Oil and gas company office spaces in downtown Calgary are subleasing 40 per cent of their overall vacancies.[133] H&R Real Estate Investment Trust, which owns the 58-storey 158,000-square-metre highrise the Bow Tower claims the building was fully leased. Tenants such as Suncor "have been letting staff and contractors go in response to the downturn."[133]

Arts and culture

Calgary has a number of multicultural areas. Forest Lawn is among the most diverse areas in the city and as such, the area around 17 Avenue SE within the neighbourhood is also known as International Avenue. The district is home to many ethnic restaurants and stores.[citation needed] Calgary was designated as one of the cultural capitals of Canada in 2012.[134]

While many Calgarians continue to live in the city's suburbs, more central districts such as 17 Avenue, Kensington, Inglewood, Forest Lawn, Marda Loop and the Mission District have become more popular and density in those areas has increased.[citation needed] The nightlife and the availability of cultural venues in these areas has gradually begun to evolve as a result.[citation needed]

The Calgary Public Library is the city's public library network, with 17 branches loaning books, e-books, CDs, DVDs, Blu-rays, audio books, and more. Based on borrowing, the library is the second largest in Canada, and sixth-largest municipal library system in North America. The 22,000-square-metre (240,000 sq ft) Calgary Central Library is under construction in Calgary East Village, and is expected to be completed in 2018.[135]

Calgary is the site of the Southern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium performing arts, culture and community facility. The auditorium is one of two "twin" facilities in the province, the other located in Edmonton, each being locally known as the "Jube". The 2,538-seat auditorium was opened in 1957[136] and has been host to hundreds of Broadway musical, theatrical, stage and local productions. The Calgary Jube is the resident home of the Alberta Ballet Company, the Calgary Opera, the Kiwanis Music Festival, and the annual civic Remembrance Day ceremonies. Both auditoriums operate 365 days a year, and are run by the provincial government. Both received major renovations as part of the province's centennial in 2005.[136]

The Alberta Ballet is the third largest dance company in Canada. Under the artistic direction of Jean Grand-Maître, the Alberta Ballet is at the forefront both at home and internationally. The dance company has developed a distinctive repertoire and a high level of performance. Jean Grand-Maître has become well known for his successful collaborations with pop-artists like Joni Mitchell, Elton John, and Sarah McLachlan. The Alberta Ballet resides in the Nat Christie Centre.[137][138][139]

The city is also home to a number of theatre companies; among them are One Yellow Rabbit, which shares the Arts Commons building with the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as Theatre Calgary, Alberta Theatre Projects and Theatre Junction GRAND, culture house dedicated to the contemporary live arts. Calgary was also the birthplace of the improvisational theatre games known as Theatresports. The Calgary International Film Festival is also held annually, as well as the International Festival of Animated Objects.[140]

Every three years, Calgary hosts the Honens International Piano Competition (formerly known as the Esther Honens International Piano Competition). The finalists of the competition perform piano concerti with the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra; the laureate is awarded a cash prize (currently $100,000.00 CDN, the largest cash award of any international piano competition), and a three-year career development program. The Honens is an integral component of the classical music scene in Calgary.

Visual and conceptual artists like the art collective United Congress are active in the city. There are a number of art galleries in the downtown along Stephen Avenue; the SoDo (South of Downtown) Design District; the 17 Avenue corridor; and the neighbourhood of Inglewood, including the Esker Foundation.[141][142] Calgary is also home to the Alberta College of Art and Design.

A number of marching bands are based in Calgary. They include the Calgary Round-Up Band, the Calgary Stetson Show Band, the Bishop Grandin Marching Ghosts, and the five-time World Association for Marching Show Bands champions, the Calgary Stampede Showband, as well as military bands including the Band of HMCS Tecumseh, the King's Own Calgary Regiment Band, and the Regimental Pipes and Drums of The Calgary Highlanders. There are many other civilian pipe bands in the city, notably the Calgary Police Service Pipe Band.[143]

Calgary is also home to a choral music community, including a variety of amateur, community, and semi-professional groups. Some of the mainstays include the Mount Royal Choirs from the Mount Royal University Conservatory, the Calgary Boys' Choir, the Calgary Girls Choir, the Youth Singers of Calgary, the Cantaré Children's Choir, and Spiritus Chamber Choir.

Calgary hosts a number of annual festivals and events. These include the Calgary International Film Festival, the Calgary Folk Music Festival, FunnyFest Calgary Comedy Festival, Sled Island music festival, Beakerhead arts, science and engineering festival, the Folk Music Festival, the Greek festival, Carifest, Wordfest, the Lilac Festival, GlobalFest, Otafest, FallCon, the Calgary Fringe Festival, Summerstock, Expo Latino, Calgary Pride, Calgary International Spoken Word Festival,[144] and many other cultural and ethnic festivals. Calgary's best-known event is the Calgary Stampede, which has occurred each July since 1912. It is one of the largest festivals in Canada, with a 2005 attendance of 1,242,928 at the 10-day rodeo and exhibition.[145]

Several museums are located in the city. The Glenbow Museum is the largest in western Canada and includes an art gallery and First Nations gallery.[146] Other major museums include the Chinese Cultural Centre (at 70,000 sq ft (6,500 m2), the largest stand-alone cultural centre in Canada),[147] the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame and Museum (at Canada Olympic Park), The Military Museums, the Cantos Music Museum and the Aero Space Museum.

Numerous films have been shot in Calgary and area. Notable films shot in and around the city include: Assassination of Jesse James, Brokeback Mountain, Dances with Wolves, Doctor Zhivago, Inception, Legends of the Fall, Unforgiven and The Revenant.[148]

The Calgary Herald and the Calgary Sun are the main newspapers in Calgary. Global, City, CTV and CBC television networks have local studios in the city.

Attractions

Downtown features an eclectic mix of restaurants and bars, cultural venues, public squares (including Olympic Plaza) and shopping. Notable shopping areas include such as The Core Shopping Centre (formerly Calgary Eaton Centre/TD Square), Stephen Avenue and Eau Claire Market. Downtown tourist attractions include the Calgary Zoo, the Telus Spark, the Telus Convention Centre, the Chinatown district, the Glenbow Museum, the Calgary Tower, the Art Gallery of Calgary (AGC), Military Museum and the EPCOR Centre for the Performing Arts. At 1.0 hectare (2.5 acres), the Devonian Gardens is one of the largest urban indoor gardens in the world,[149] and it is located on the 4th floor of The Core Shopping Centre (above the shopping). The downtown region is also home to Prince's Island Park, an urban park located just north of the Eau Claire district. Directly to the south of downtown is Midtown and the Beltline. This area is quickly becoming one of the city's densest and most active mixed use areas.[citation needed] At the district's core is the popular 17 Avenue, known for its many bars and nightclubs, restaurants, and shopping venues. During the Calgary Flames' playoff run in 2004, 17 Avenue was frequented by over 50,000 fans and supporters per game night. The concentration of red jersey-wearing fans led to the street's playoff moniker, the "Red Mile". Downtown is easily accessed using the city's C-Train light rail (LRT) transit system.

Attractions on the west side of the city include the Heritage Park Historical Village historical park, depicting life in pre-1914 Alberta and featuring working historic vehicles such as a steam train, paddle steamer and electric streetcar. The village itself comprises a mixture of replica buildings and historic structures relocated from southern Alberta. Other major city attractions include Canada Olympic Park, which features Canada's Sports Hall of Fame, and Spruce Meadows. In addition to the many shopping areas in the city centre, there are a number of large suburban shopping complexes in the city. Among the largest are Chinook Centre and Southcentre Mall in the south, Westhills and Signal Hill in the southwest, South Trail Crossing and Deerfoot Meadows in the southeast, Market Mall in the northwest, Sunridge Mall in the northeast, and the newly built CrossIron Mills just north of the Calgary city limits, and south of the City of Airdrie.

In nearby Airdrie at the Calgary/Airdrie Airport the Airdrie Regional Airshow is held every two years. In 2011 the airshow featured the Canadian Snowbirds, a CF-18 demo and a United States Air Force F-16.[150][151]

Tallest buildings

Downtown can be recognized by its numerous skyscrapers. Some of these structures, such as the Calgary Tower and the Scotiabank Saddledome are unique enough to be symbols of Calgary. Office buildings tend to concentrate within the commercial core, while residential towers occur most frequently within the Downtown West End and the Beltline, south of downtown. These buildings are iconographic of the city's booms and busts, and it is easy to recognize the various phases of development that have shaped the image of downtown. The first skyscraper building boom occurred during the late 1950s and continued through to the 1970s.[citation needed] After 1980, during the recession, many high-rise construction projects were immediately halted.[citation needed] It was not until the late 1980s and through to the early 1990s that major construction began again, initiated by the 1988 Winter Olympics and stimulated by the growing economy.[citation needed]

In total, there are 14 office towers that are at least 150 m (490 ft) (usually around 40 floors) or higher. The tallest of these is Brookfield Place, which is the tallest office tower in Canada outside Toronto.[152] Calgary's Bankers Hall Towers are also the tallest twin towers in Canada. As of 2008, there were 264 completed high-rise buildings, with 42 more under construction, another 13 approved for construction and 63 more proposed.[citation needed]

Sports and recreation

In large part due to its proximity to the Rocky Mountains, Calgary has traditionally been a popular destination for winter sports. Since hosting the 1988 Winter Olympics, the city has also been home to a number of major winter sporting facilities such as Canada Olympic Park (bobsleigh, luge, cross-country skiing, ski jumping, downhill skiing, snowboarding, and some summer sports) and the Olympic Oval (speed skating and hockey). These facilities serve as the primary training venues for a number of competitive athletes. Also, Canada Olympic Park serves as a mountain biking trail in the summer months.

In the summer, the Bow River is very popular among fly-fishermen. Golfing is also an extremely popular activity for Calgarians and the region has a large number of courses.[citation needed]

Calgary hosted the 2009 World Water Ski Championship Festival in August, at the Predator Bay Water Ski Club, approximately 40 km (25 mi) south of the city.[citation needed]

As part of the wider Battle of Alberta, the city's sports teams enjoy a popular rivalry with their Edmonton counterparts, most notably the rivalries between the National Hockey League's Calgary Flames and Edmonton Oilers, and the Canadian Football League's Calgary Stampeders and Edmonton Eskimos.[citation needed]

Calgary is renowned in professional wrestling tradition as both the home-city of the prominent Hart wrestling family and the location of the infamous Hart family "Dungeon", wherein WWE Hall of Fame member and patriarch of the Hart Family, Stu Hart,[153] trained numerous professional wrestlers including Superstar Billy Graham, Brian Pillman, the British Bulldogs, Edge, Christian, Greg Valentine, Chris Jericho, Jushin Thunder Liger and many more. Also among the trainees were the Hart family members themselves, including WWE Hall of Fame member and former WWE champion Bret Hart and his brother, the 1994 WWF King of the Ring, Owen Hart.[153]

In 1997 Calgary hosted The World Police & Fire Games hosting over 16,000 athletes from all over the world.

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary Stampeders | Canadian Football League | McMahon Stadium | 1945 | 7 |

| Calgary Flames | National Hockey League | Scotiabank Saddledome | 1980 | 1 |

| Calgary Roughnecks | National Lacrosse League | Scotiabank Saddledome | 2001 | 2 |

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary Crush | American Basketball Association | SAIT | 2011 | 0 |

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary Canucks | Alberta Junior Hockey League | Max Bell Centre | 1971 | 9 |

| Calgary Mustangs | Alberta Junior Hockey League | Father David Bauer Olympic Arena | 1990 | 1 |

| Calgary Hitmen | Western Hockey League | Scotiabank Saddledome | 1995 | 2 |

| Calgary Inferno | Canadian Women's Hockey League | Olympic Oval | 2011 | 1 |

| Calgary Mavericks | Rugby Canada National Junior Championship | Calgary Rugby Park | 1998 | 1 |

Within Calgary there are approximately 8,000 ha (20,000 acres) of parkland available for public usage and recreation.[154] These parks include Fish Creek Provincial Park, Inglewood Bird Sanctuary, Bowness Park, Edworthy Park, Confederation Park, Prince’s Island Park, Nose Hill Park, and Central Memorial Park. Nose Hill Park is one of the largest municipal parks in Canada at 1,129 ha (2,790 acres). The park has been subject to a revitalization plan that began in 2006. Its trail system is currently undergoing rehabilitation in accordance with this plan.[155][156] The oldest park in Calgary, Central Memorial Park, dates back to 1911. Similar to Nose Hill Park, revitalization also took place in Central Memorial Park in 2008–2009 and reopened to the public in 2010 while still maintaining its Victorian style.[157] A 800 km (500 mi) pathway system connects these parks and various neighbourhoods.[154][158]

Calgary also has multiple private sporting clubs including the Glencoe Club and the Calgary Winter Club.

Government

The city is a corporate power-centre, a high percentage of the workforce is employed in white-collar jobs. The high concentration of oil and gas corporations led to the rise of Peter Lougheed's Progressive Conservative Party in 1971.[159] However, as Calgary's population has increased, so has the diversity of its politics.

Municipal politics

Calgary is governed in accordance with Alberta's Municipal Government Act (1995).[160] Calgarians elect 14 ward councillors and a mayor to Calgary City Council every four years. Naheed Nenshi was first elected mayor in the 2010 municipal election. Naheed Nenshi was re-elected in 2013 and 2017.

Three school boards operate independently of each other in Calgary, the public, the separate (catholic) and francophone systems. Both the public and separate boards have 7 elected trustees each representing 2 of 14 wards. The School Boards are considered to be part of municipal politics in Calgary as they are elected at the same time as City Council.[161]

Provincial politics

As a result of the 2015 provincial election, Calgary is represented by twenty-five MLAs, including fifteen New Democrats, seven Progressive Conservatives, and one member each of the Wildrose Party, Alberta Party and Alberta Liberal Party.[162] During this election, the Alberta Party won its first-ever seat, with MLA Greg Clark in the Calgary-Elbow riding. The Progressive Conservative Party had the most to lose, losing 13 of the seats it previously held.

Federal politics

On October 19, 2015, Calgary elected its first two Liberal federal MPs since 1968, Darshan Kang for Calgary Skyview and Kent Hehr for Calgary Centre.[163] The remaining MPs are members of the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC).[164] Before 2015, the Liberals had only elected three MPs from Calgary ridings in their entire history-- Manley Edwards (1940–1945),[165] Harry Hays (1963–1965)[166] and Pat Mahoney (1968–1972).[167]

The federal riding of Calgary Heritage was held by former Prime Minister and CPC leader Stephen Harper. That seat was also held by Preston Manning, the leader of the Reform Party of Canada; it was known as Calgary Southwest at the time. Harper is the second Prime Minister to represent a Calgary riding; the first was R. B. Bennett from Calgary West, who held that position from 1930 to 1935. Joe Clark, former Prime Minister and former leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada (also a predecessor of the CPC), held the riding of Calgary Centre during his second stint in Parliament from 2000 to 2004.

The Green Party of Canada has also made inroads in Calgary, exemplified by results of the 2011 federal election where they achieved 7.7% of the vote across the city, ranging from 4.7% in Calgary Northeast to 13.1% in Calgary Centre-North.[168]

Crime

The Calgary census metropolitan area (CMA) had a crime severity index of 60.4 in 2013, which is lower than the national average of 68.7.[169] A slight majority of the other CMAs in Canada had crime severity indexes greater than Calgary's 60.4.[169] Calgary had the sixth-most homicides in 2013 at 24.[169]

Military

The presence of the Canadian military has been part of the local economy and culture since the early years of the 20th century, beginning with the assignment of a squadron of Strathcona's Horse. After many failed attempts to create the city's own unit, the 103rd Regiment (Calgary Rifles) was finally authorized on April 1, 1910. Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Calgary was established as Currie Barracks and Harvie Barracks following the Second World War. The base remained the most significant Department of National Defence (DND) institution in the city until it was decommissioned in 1998, when most of the units moved to CFB Edmonton. Despite this closure there is still a number of Canadian Forces Reserve units, and cadet units garrisoned throughout the city. They include HMCS Tecumseh Naval Reserve unit, The King's Own Calgary Regiment, The Calgary Highlanders, both headquartered at the Mewata Armouries, 746 Communication Squadron, 41 Canadian Brigade Group, headquartered at the former location of CFB Calgary, 14 (Calgary) Service Battalion, 15 (Edmonton) Field Ambulance Detachment Calgary, 14 (Edmonton) Military Police Platoon Calgary, 41 Combat Engineer Regiment detachment Calgary (33 Engineer Squadron), along with a small cadre of Regular Force support. Several units have been granted Freedom of the City.

The Calgary Soldiers' Memorial commemorates those who died during wartime or while serving overseas. Along with those from units currently stationed in Calgary it represents the 10th Battalion, CEF and the 50th Battalion, CEF of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Calgary International Airport (YYC), in the city's northeast, is a transportation hub for much of central and western Canada. In 2013 it was the third busiest in Canada by passenger movement,[170] and third busiest by aircraft movements,[171] is a major cargo hub,[citation needed] and is a staging point for people destined for Banff National Park.[172] Non-stop destinations include cities throughout Canada, the United States, Europe, Central America, and Asia. Calgary/Springbank Airport, Canada's eleventh busiest,[171] serves as a reliever for the Calgary International taking the general aviation traffic and is also a base for aerial firefighting aircraft.

Calgary's presence on the Trans-Canada Highway and the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) mainline (which includes the CPR Alyth Yard) also make it an important hub for freight. The Rocky Mountaineer and Royal Canadian Pacific operates railtour service to Calgary; Via Rail no longer provides intercity rail service to Calgary since the company discontinued the Super Continental via Edmonton in 1990 and then rerouted The Canadian from Calgary to serve Edmonton.[citation needed]

Much of Calgary's street network is on a grid where roads are numbered with avenues running east–west and streets running north–south. Until 1904 the streets were named; after that date, all streets were given numbers radiating outwards from the city centre.[173] Roads in predominantly residential areas as well as freeways and expressways do not generally conform to the grid and are usually not numbered as a result. However, it is a developer and city convention in Calgary that non-numbered streets within a new community have the same name prefix as the community itself so that streets can more easily be located within the city.

Calgary Transit provides public transportation services throughout the city with buses and light rail. Calgary's light rail system, known as the C-Train, was one of the first such systems in North America (behind Edmonton LRT). It consists of four lines (two routes) and 44 stations on 58.2 km (36.2 mi) of track. The Calgary LRT is one of the continent's busiest carrying 270,000 passengers per weekday and approximately half of Calgary downtown workers take the transit to work. The C-Train is also North America's first and only LRT to run on 100% renewable energy.[174]

As an alternative to the over 260 km (160 mi) of shared bikeways on streets, the city has a network of multi-use (bicycle, walking, rollerblading, etc.) paths spanning over 635 km (395 mi).[158] The Peace Bridge provides pedestrians and cyclists, access to the downtown core from the north side of the Bow river. The bridge ranked among the top 10 architectural projects in 2012 and among the top 10 public spaces of 2012.[175]

In the 1960s, Calgary started to develop a series of pedestrian bridges, connecting many downtown buildings.[176] To connect many of the downtown office buildings, the city also boasts the world's most extensive skyway network (elevated indoor pedestrian bridges), officially called the +15. The name derives from the fact that the bridges are usually 15 ft (4.6 m) above ground.[177]

Health care

- Medical centres and hospitals

Calgary has four major adult acute care hospitals and one major pediatric acute care site: the Alberta Children's Hospital, the Foothills Medical Centre, the Peter Lougheed Centre, the Rockyview General Hospital and the South Health Campus. They are all overseen by the Calgary Zone of the Alberta Health Services, formerly the Calgary Health Region. Calgary is also home to the Tom Baker Cancer Centre (located at the Foothills Medical Centre), the Grace Women's Health Centre, which provides a variety of care, and the Libin Cardiovascular Institute. In addition, the Sheldon M. Chumir Centre (a large 24-hour assessment clinic), and the Richmond Road Diagnostic and Treatment Centre (RRDTC), as well as hundreds of smaller medical and dental clinics operate in Calgary. The Faculty of Medicine of the University of Calgary also operates in partnership with Alberta Health Services, by researching cancer, cardiovascular, diabetes, joint injury, arthritis and genetics.[178] The Alberta children's hospital, built in 2006, replaced the old Children's Hospital.

The four largest Calgary hospitals have a combined total of more than 2,100 beds, and employ over 11,500 people.[179]

Education

Primary and secondary

In the 2011–2012 school year, 100,632 K-12 students enrolled in 221 schools in the English language public school system run by the Calgary Board of Education.[180] With other students enrolled in the associated CBe-learn and Chinook Learning Service programs, the school system's total enrolment is 104,182 students.[180] Another 43,000 attend about 95 schools in the separate English language Calgary Catholic School District board.[181] The much smaller Francophone community has their own French language school boards (public and Catholic), which are both based in Calgary, but serve a larger regional district. There are also several public charter schools in the city. Calgary has a number of unique schools, including the country's first high school exclusively designed for Olympic-calibre athletes, the National Sport School.[182] Calgary is also home to many private schools including Mountain View Academy, Rundle College, Rundle Academy, Clear Water Academy, Calgary French and International School, Chinook Winds Adventist Academy, Webber Academy, Delta West Academy, Masters Academy, Calgary Islamic School, Menno Simons Christian School, West Island College, Edge School, Calgary Christian School, Heritage Christian Academy, Bearspaw Christian School.

Calgary is also home to what was Western Canada's largest public high school, Lord Beaverbrook High School, with 2,241 students enrolled in the 2005–2006 school year.[183] Currently the student population of Lord Beaverbrook is 1,812 students (September 2012) and several other schools are equally as large; Western Canada High School with 2,035 students (2009) and Sir Winston Churchill High School with 1,983 students (2009).

Post-secondary

The publicly funded University of Calgary (U of C) is Calgary's largest degree-granting facility with an enrolment of 28,464 students in 2011.[184] Mount Royal University, with 13,000 students, grants degrees in a number of fields. SAIT Polytechnic, with over 14,000 students, provides polytechnic and apprentice education, granting certificates, diplomas and applied degrees. Athabasca University provides distance education programs.

Other publicly funded post-secondary institutions based in Calgary include the Alberta College of Art and Design, Ambrose University College (associated with the Christian and Missionary Alliance and the Church of the Nazarene), Bow Valley College, Mount Royal University, SAIT Polytechnic, St. Mary's University and the U of C.[185] The publicly funded Athabasca University, Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT), and the University of Lethbridge[185] also have campuses in Calgary.[186][187][188]

Several independent private institutions are located in the city. This includes Reeves College, MaKami College, Robertson College, Columbia College, and CDI College. DeVry Institute of Technology announced the closure of its Calgary campus operations on June 30, 2013.[189]

Media

Calgary's daily newspapers include the Calgary Herald, Calgary Sun and Metro News.

Calgary is the sixth largest television market in Canada.[190] Broadcasts stations serving Calgary include CICT 2 (Global), CFCN 4 (CTV), CKAL 5 (City), CBRT 9 (CBC), CKCS 32 (YesTV), and CJCO 38 (Omni). Network affiliate programming from the United States originates from Spokane, Washington.

There are a wide range of radio stations, including a station for First Nations and the Asian Canadian community.

Notable people

Sister cities

The City of Calgary maintains trade development programs, cultural and educational partnerships in twinning agreements with six cities:[191][192]

| City | Province/State | Country | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec City | Quebec | Canada | 1956 |

| Jaipur | Rajasthan | India | 1973 |

| Naucalpan | Mexico State | Mexico | 1994 |

| Daqing | Heilongjiang | China | 1985 |

| Daejeon | Chungnam | South Korea | 1996 |

| Phoenix[193] | Arizona | US | 1997 |

Calgary is one of nine Canadian cities, out of the total of 98 cities internationally, that is in the New York City Global Partners, Inc. organization,[194] which was formed in 2006 from the former Sister City program of the City of New York, Inc.[195]

See also

References

- ^ Eric Volmers (May 13, 2012). "Alberta's best in TV, film feted at Rosies". Calgary Herald. Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Curtis Stock (July 7, 2009). "Alberta's got plenty of swing". Calgary Herald. Postmedia Network. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Fromhold, Joachim (2001). 2001 Indian Place Names of the West - Part 1. Calgary: Lulu. pp. CCC.

- ^ Fromhold, Joachim (2001). 2001 INDIAN PLACE NAMES OF THE WEST, Part 2: Listings by Nation. Calgary: Lulu. p. 24.

- ^ "Location and History Profile: City of Calgary" (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. June 17, 2016. p. 15. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Municipal Officials Search". Alberta Municipal Affairs. May 9, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and population centres, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "Alberta Private Sewage Systems 2009 Standard of Practice Handbook: Appendix A.3 Alberta Design Data (A.3.A. Alberta Climate Design Data by Town)" (PDF) (PDF). Safety Codes Council. January 2012. pp. 212–215 (PDF pages 226–229). Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ "City Releases 2017 Census Results". City of Calgary. July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Calgary-Edmonton Corridor". Statistics Canada. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ "Calgary Industries". Calgary Economic Development.

- ^ a b c "State of the West 2010: Western Canadian Demographic and Economic Trends" (PDF) (PDF). Canada West Foundation. 2010. pp. 65 & 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Why Calgary? Our Economy in Depth" (PDF). Calgary Economic Development. 2018. p. 61. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ "Vancouver, Toronto, Calgary named to list of the world's most livable cities". CTV News. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ a b Alberta Place Names : The Fascinating People & Stories Behind the Naming of Alberta. Dragon Hill Publishing Ltd. 2006. p. 34.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ [full citation needed] Mull Museum, Tobermory, Isle of Mull, Scotland. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Fromhold, Joachim (2001). 2001 Indian Place Names of the West - Part 1. Calgary: Lulu. pp. CCC.

- ^ Fromhold, Joachim (2001). 2001 INDIAN PLACE NAMES OF THE WEST, Part 2: Listings by Nation. Calgary: Lulu. p. 24.

- ^ a b c d "7 names for Calgary before it became Calgary". CBC News. December 3, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ^ Klaszus, Jeremy (October 18, 2017). "How Naheed Nenshi's Tense Re-election Forces Us to Confront Canadian Racism". The Walrus. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ Nenshi, Naheed. "FINA: Standing Committee on Finance NUMBER 114 ● 1st SESSION ● 42nd PARLIAMENT. EVIDENCE Friday, October 6, 2017" (PDF). Standing Committee on Finance. 114: 8 – via www.ourcommons.ca.

We all know that until the Fort McMurray wildfires last year, the flooding in southern Alberta in 2013 was the costliest natural disaster in Canadian history. While we have done great work in the four years since, within the city of Calgary we continue to need assistance in upstream flood mitigation. Calgary is a city that is built at the confluence of two rivers in a place the Blackfoot called Moh-Kins-Tsis, the elbow. We can't move the city. We can't make room for the river. This is where the rivers are. As a result, it is incredibly important that we do the engineering work on the upstream mitigation.

- ^ a b Wilkes, Rima; Duong, Aaron; Kesler, Linc; Ramos, Howard (February 21, 2017). "Canadian University Acknowledgment of Indigenous Lands, Treaties, and Peoples". Canadian Review of Sociology. 54: 89–102. doi:10.1111/cars.12140 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ a b "Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory". Canadian Association of University Teachers. November 19, 2017.

- ^ "Visit Esker Foundation". Esker Foundation. November 20, 2017.

It is important to acknowledge and reflect upon the fact that Esker Foundation is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikuni, the Kainai, the Tsuut'ina, and the Stoney Nakoda First Nations. We are also situated on land adjacent to where the Bow River meets the Elbow River; the traditional Blackfoot name of this place is Mohkinstsis, which we now call the City of Calgary. The City of Calgary is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region III.

- ^ "University of Calgary Recommended Acknowledgements of Traditional Indigenous Territories" (PDF). University of Calgary. November 19, 2017.

Welcome to the University of Calgary. I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the traditional territories of the Blackfoot and the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikuni, the Kainai, the Tsuut'ina, and the Stoney Nakoda First Nations, including Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nation. I would also like to note that the University of Calgary is situated on land adjacent to where the Bow River meets the Elbow River, and that the traditional Blackfoot name of this place is "Mohkinstsis" which we now call the City of Calgary. The City of Calgary is also home to Métis Nation of Alberta, Region III.

- ^ "Treaty 7 Territory Acknowledgement". Bow Valley College. November 19, 2017. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

We are located in the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy) and the people of the Treaty 7 region in Southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut'ina and the Iyarhe Nakoda. We are situated on land where the Bow River meets the Elbow River, and the traditional Blackfoot name of this place is "Mohkinstsis" which we now call the City of Calgary. The City of Calgary is also home to Metis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Oki (Welcome) to the Iniskim Centre". Mount Royal University. November 19, 2017.

Mount Royal University is located in the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of the Treaty 7 region in southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikuni, the Kainai, the Tsuut'ina and the Iyarhe Nakoda. We are situated on land where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. The traditional Blackfoot name of this place is "Mohkinstsis," which we now call the city of Calgary. The city of Calgary is also home to the Métis Nation.

- ^ The Canadian Press (November 13, 2017). "What's in a name? For Alberta First Nations seeking heritage recognition, plenty". CBC News.

- ^ Kaufmann, Bill (November 17, 2017). "Piikani Blackfoot dispute Stoney Nakoda push on name changes for Calgary, other locales". The Calgary Herald. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ University of Calgary. "Archaeology Timeline of Alberta". Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- ^ "The Glenns". Alberta Tourism Parks, Recreation and Culture. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ "CP Rail moving headquarters from glass tower in Calgary to nearby rail yard: union source". Financial Post. Postmedia Network Inc. November 23, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ City of Calgary. "Historical Information". Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ Ward, Tom (1975). Cowtown : an album of early Calgary. Calgary: City of Calgary Electric System, McClelland and Stewart West. p. 274. ISBN 0-7712-1012-4.

- ^ "The Great Fire of 1886". Archived from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Sandstone City". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ "Hudson's Bay Company – Our History". hbc.com.

- ^ "Hbc Heritage – Early Stores". hbcheritage.ca. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Byfield, Ted (1992). The Birth of the province. Edmonton: United Western Communications. p. 156. ISBN 096957181X.

- ^ "Stampede History - Calgary Stampede". corporate.calgarystampede.com. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ "Yahoo! Stampede parade kicks off 'greatest outdoor show on earth'".

- ^ CBC Article. "Oil and Gas in Alberta". Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ Calgary architecture : the boom years, 1972–1982, Pierre S Guimond; Brian R Sinclair, Detselig Enterprises, 1984, ISBN 0-920490-38-7.

- ^ Inflation Data. "Historical oil prices". Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ Debra J. Davidson; Mike Gismondi (2011). Challenging Legitimacy at the Precipice of Energy Calamity. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4614-0287-9.

- ^ University of Calgary (1998). "Calgary's History 1971–1991". Archived from the original on June 1, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Calgary Public Library. "Calgary Timeline". Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ Staff. "The Winter of '88: Calgary's Olympic Games". CBC Sports. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ The Conference Board of Canada (2005). "Western cities enjoy fastest growing economies". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Alberta Tourism (2004). "Tourism in Calgary and Area; Summary of Visitor Numbers and Revenue" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "LIVE: Stampede confirms 101st edition will go ahead". www.calgaryherald.com.

- ^ "Alberta flooding claims at least 3 lives". cbc.ca. June 22, 2013.

- ^ Government of Alberta. "Alberta Natural Regions". Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Calgary International Airport Zoning Regulations". Justice Laws Website. Government of Canada. August 4, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ "Statistics Profile" (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. March 24, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Services, Community & Neighbourhood (April 1, 2011). "Community Profiles". www.calgary.ca. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Your Official Road Map of Alberta (Map) (2015 ed.). Travel Alberta. 2015. ISBN 9781460120767.

- ^ "Elbow Valley Area Map" (PDF) (PDF). Rocky View County. May 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Springbank Area Map" (PDF) (PDF). Rocky View County. May 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Bearspaw Area Map" (PDF) (PDF). Rocky View County. May 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Annexation Information". City of Calgary. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca distribution map at Flora of North America

- ^ City of Calgary. "Beltline—Area Redevelopment Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ City of Calgary (January 2007). "Community Profiles". Retrieved February 14, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Calgary International Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ "Plant Hardiness Zone by Municipality". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Ward Cameron. "Learn about the Famous Chinook Winds". mountainnature.com.

- ^ "Average Annual Wind Speed at Canadian Cities".

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000 Station Data". Environment Canada. Environment Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Hourly Data Report for July 15, 1999". Environment Canada. Environment Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Canada's Top Ten Weather Stories of 1999 (Archived)". Environment Canada. Environment Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Stormiest Canadian Cities - Current Results". www.currentresults.com. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ The Atlas of Canada (April 2004). "Major Hailstorms". Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for July 1933". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Table IX: Population of cities, towns and incorporated villages in 1906 and 1901 as classed in 1906". Census of the Northwest Provinces, 1906. Vol. Sessional Paper No. 17a. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1907. p. 100.

- ^ "Table I: Area and Population of Canada by Provinces, Districts and Subdistricts in 1911 and Population in 1901". Census of Canada, 1911. Vol. Volume I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1912. pp. 2–39.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Table I: Population of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta by Districts, Townships, Cities, Towns, and Incorporated Villages in 1916, 1911, 1906, and 1901". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1916. Vol. Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1918. pp. 77–140.

- ^ "Table 8: Population by districts and sub-districts according to the Redistribution Act of 1914 and the amending act of 1915, compared for the census years 1921, 1911 and 1901". Census of Canada, 1921. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1922. pp. 169–215.

- ^ "Table 7: Population of cities, towns and villages for the province of Alberta in census years 1901–26, as classed in 1926". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1926. Vol. Census of Alberta, 1926. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1927. pp. 565–567.

- ^ "Table 12: Population of Canada by provinces, counties or census divisions and subdivisions, 1871–1931". Census of Canada, 1931. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1932. pp. 98–102.

- ^ "Table 4: Population in incorporated cities, towns and villages, 1901–1936". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1936. Vol. Volume I: Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1938. pp. 833–836.