Hyderabad: Difference between revisions

added Category:Telangana using HotCat |

chopped biased edits and restored deccan as a geographical region and telengana category, please discuss on talk page. |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Andhra Pradesh]] |

| subdivision_name1 = [[Andhra Pradesh]] |

||

| subdivision_type2 = [[List of regions of India|Region]] |

| subdivision_type2 = [[List of regions of India|Region]] |

||

| subdivision_name2 = [[ |

| subdivision_name2 = [[Deccan]] |

||

| subdivision_type3 = [[List of districts of India|Districts]] |

| subdivision_type3 = [[List of districts of India|Districts]] |

||

| subdivision_name3 = [[Hyderabad district, India|Hyderabad]], [[Rangareddy district|Rangareddy]] and [[Medak district|Medak]] |

| subdivision_name3 = [[Hyderabad district, India|Hyderabad]], [[Rangareddy district|Rangareddy]] and [[Medak district|Medak]] |

||

| Line 465: | Line 465: | ||

[[Category:Articles with images not understandable by color blind users]] |

[[Category:Articles with images not understandable by color blind users]] |

||

[[Category:Templates with incorrect parameter syntax]] |

[[Category:Templates with incorrect parameter syntax]] |

||

[[Category:Telangana]] |

|||

{{Link GA|simple}} |

{{Link GA|simple}} |

||

Revision as of 14:24, 9 April 2013

Hyderabad | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Charminar, Birla Mandir, Hussain Sagar, Golconda Fort, Skyline at Lanco Hills, Chowmahalla Palace. | |

| Nickname: City of Pearls | |

| Country | |

| State | Andhra Pradesh |

| Region | Deccan |

| Districts | Hyderabad, Rangareddy and Medak |

| Founded | 1591 AD |

| Founded by | Mohammed Quli Qutub Shah |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | GHMC, HMDA |

| • MP | Asaduddin_Owaisi |

| • Mayor | Mohammad Majid Hussain |

| • Police commissioner | Anurag Sharma |

| Area | |

| • Metropolis | 650 km2 (250 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Metropolis | 6,809,970 |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Density | 18,480/km2 (47,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,749,334 |

| • Metro rank | 6th |

| Demonym | Hyderabadi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Pincode(s) | 500 xxx, 501 xxx, 502 xxx, 508 xxx, 509 xxx |

| Area code(s) | +91–40, 8413, 8414, 8415, 8417, 8418, 8453, 8455 |

| Vehicle registration | AP 09, 10, 11, 12, 13, 22, 23, 24, 28 & 29 |

| Official languages | Telugu; Urdu |

| Website | www |

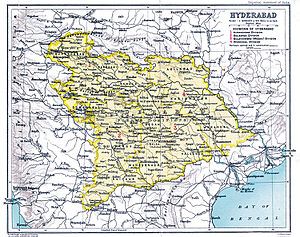

Hyderabad (/ˈhaɪdərəbæd/ ) is the capital and largest city of the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies 650 square kilometres (250 sq mi) on the banks of the Musi River. As of 2011, the population of the city was 6.8 million while the metropolitan area had a population of 7.75 million, making it India's fourth most populous city and sixth most populous urban agglomeration.

Hyderabad was established in 1591 CE by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, fifth sultan of the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golkonda. It remained under the rule of the Qutb Shahi dynasty until 1687, when Mughal emperor Aurangzeb conquered the region and the city became part of the Mughal empire. In 1724 Asif Jah I, a Mughal viceroy, declared his sovereignty and formed the Asif Jahi dynasty, also known as the Nizams of Hyderabad. The Nizams ruled the princely state of Hyderabad in a subsidiary alliance with the British Raj for more than two centuries. The city remained the princely state's capital from 1769 to 1948, when the Nizam signed an Instrument of Accession with the Indian Union as a result of Operation Polo. Between 1948-1956 Hyderabad city was the capital of the Hyderabad State. In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act merged Hyderabad State with the Andhra State to form the modern state of Andhra Pradesh, with Hyderabad city as its capital.

Throughout its history, the city was a centre for local traditions in art, literature, architecture and cuisine. It is a tourist destination and has many places of interest, including Chowmahalla Palace, Charminar and Golkonda fort. It has several museums such as Salar Jung Museum, Nizam Museum, and AP State Archaeology Museum, bazaars such as Laad Bazar, Madina Circle, Begum Bazaar and Sultan Bazaar from the Qutb Shahi and Nizam era, galleries, libraries, sports venues and other cultural institutions. Hyderabadi biriyani and Hyderabadi haleem are examples of distinctive culinary products of the city.

Historically, Hyderabad was known for its pearl and diamond trading centres. Industrialisation brought major Indian manufacturing and financial institutions to the city, such as the Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, the Defence Research and Development Organisation, the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology and the National Mineral Development Corporation. The formation of information technology (IT) Special Economic Zone (SEZ) by the state agencies attracted global and Indian companies to set up operations in the city. The emergence of pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries from the 1990s earned it the titles of "India's pharmaceutical capital" and the "Genome Valley of India". The Telugu film industry is based in Hyderabad.

History

Toponymy

The name Hyderabad means "Hyder's abode" or "lion city", derived from the Persian/Urdu words "haydar" or "hyder" (lion) and "ābād" (city or abode).[1] According to John Everett-Heath, Hyderabad was named to honour the Caliph Ali Ibn Abi Talib, who was also known as Hyder because of his lion-like valour in battles.[1] One popular theory suggests that Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the founder of the city, named it "Bhaganagar" or "Bhāgnagar" after Bhāgmathi, a local nautch (dancing) girl with whom he had fallen in love.[2] She converted to Islam and adopted the title Hyder Mahal. The city was renamed Hyderabad in her honour.[2] According to another source, the city was named after Haidar, the son of Quli Qutb Shah.[3] Andrew Petersen, a scholar of Islamic architecture, says the city was originally called Baghnagar (city of gardens).[4] However, no sources define when or by whom the city was named.

Early and medieval history

Archaeologists excavating near the city have unearthed Iron Age sites that may date from 500 BCE.[5] The region comprising modern Hyderabad and its surroundings was known as Golkonda ("shepherd's hill"),[6] and was ruled by the Chalukya dynasty from 624 CE to 1075 CE.[7] Following the dissolution of the Chalukya empire into four parts in the 11th century, Golkonda came under the control of the Kakatiya dynasty (1158–1310), whose headquarters was at Warangal, 148 km (92 mi) northeast of modern Hyderabad.[8]

When Sultan Alauddin Khilji of the Delhi Sultanate took over Warangal after a long siege, the Kakatiya dynasty was allowed to rule the region under the subjugate of the Khilji dynasty (1310–1321), until 1321 when the Kakatiya dynasty was annexed to Allaudin Khilji general Malik Kafur.[9] Alauddin Khilji took the Koh-i-Noor diamond, which is said to have been mined from the Kollur Mines in Golkonda,[10] to Delhi. Muhammad bin Tughluq succeeded to the Delhi sultanate in 1325, bringing Warangal under the rule of the Tughlaq dynasty until 1347 when Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah, a governor under bin Tughluq, rebelled against the sultanate and established the Bahmani Sultanate in the Deccan Plateau, with Gulbarga, 200 km (124 mi) west of Hyderabad, as its capital. The Bahmani kings ruled the region until 1518, and were the first independent Muslim rulers of the Deccan.[8]

Sultan Quli, a governor of Golkonda, revolted against the Bahmani Sultanate and established the Qutb Shahi dynasty in 1518.[8] Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the fifth sultan of this dynasty, established Hyderabad on the banks of the Musi River in 1591[11] to avoid the water shortages experienced at Golkonda, the sultanate's capital.[12] He built the Charminar and Mecca Masjid in the city.[13] On 21 September 1687, the Golkonda Sultanate came under the rule of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb after a year-long siege of the Golkonda fort.[14][15] The annexed area was renamed Deccan Suba (Deccan province), and the capital was moved from Golkonda to Aurangabad, about 550 km (342 mi) northwest of Hyderabad.[14][16]

Nizam period

In 1712, Farrukhsiyar, the sixth of Aurangzeb's successors, appointed Asif Jah I to be Viceroy of the Deccan, with the title Nizam-ul-Mulk (Administrator of the Realm). In 1724, Asif Jah I defeated Mubariz Khan to establish autonomy over the Deccan Suba, starting what came to be known as the Asif Jahi dynasty. He named the region Hyderabad Deccan. Subsequent rulers retained the title Nizam ul-Mulk and were referred to as Asif Jahi Nizams, or Nizams of Hyderabad.[14][16] When Asif Jah I died in 1748, there was political unrest due to contention for the throne among his sons, who were aided by opportunistic neighbouring states and colonial foreign forces. Asif Jah II, who reigned from 1762 to 1803, ended the instability. In 1768 he signed the treaty of Masulipatnam, surrendering the coastal region to the East India Company in return for a fixed annual rent.[17]

In 1769, Hyderabad city became the formal capital of the Nizams.[14][16] In response to regular threats from Hyder Ali, Dalwai of Mysore, Baji Rao I, Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, and Basalath Jung (Asif Jah II's elder brother, who was supported by the Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau), the Nizam signed a subsidiary alliance with the East India Company in 1798, allowing the British Indian Army to occupy Bolarum (modern Secunderabad) to protect the state's borders, for which the Nizams paid an annual maintenance to the British.[17] From the late nineteenth century on, Hyderabad was transformed into a modern city with the establishment of railways, transport services, underground drainage, running water, electricity, Begumpet Airport, telecommunications, universities and industries. The Nizams ruled the state from Hyderabad until 17 September 1948, a year after India's independence from Britain.[14][16]

Post-independence

Following the independence of India from British rule, the Nizam declared his intention to remain independent rather than become part of the Indian Union.[17] The Hyderabad State Congress, with the support of the Indian National Congress and the Communist Party of India, began agitating against Nizam VII in 1948. On 17 September 1948, the Indian Army took control of Hyderabad State after an invasion codenamed Operation Polo. When his forces were defeated, Nizam VII capitulated to the Indian Union by signing the "Instrument of Accession", which made him the Rajpramukh (Princely Governor) of the state until 31 October 1956.[16][18] Between 1946 and 1951, the Communist Party of India led a peasant rebellion called the Telangana uprising against the feudal lords of the Telangana region and later against the princely state of Hyderabad.[19] The Constitution of India, which became effective on 26 January 1950, made Hyderabad State one of the part B states of India, with Hyderabad City continuing to be the capital. In his 1955 report Thoughts on Linguistic States, B. R. Ambedkar, then chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution, proposed designating the Hyderabad city as the second capital of India because of its amenities and strategic central location.[20] Since 1956, the Rashtrapati Nilayam in Hyderabad has been the second official residence and business office of the President of India.[21]

On 1 November 1956, the states of India were reorganised by language group. Hyderabad State ceased to exist; it was split into three parts, which were included in the modern Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The nine Telugu- and Urdu-speaking districts of Hyderabad State that make up the Telangana region were merged with the Telugu-speaking Andhra State to create Andhra Pradesh,[22] with Hyderabad as its capital. Several protests, known collectively as the Telangana movement, attempted to invalidate the merger and demanded the creation of a new Telangana state. Major actions took place in 1969 and 1972, with a third beginning in 2010.[23] In 2002, a blast in Dilsukhnagar claiming two lives.[24] In May and August 2007, terrorist groups detonated a series of bombs in the city, causing communal tension and riots.[25] The series of blasts that occurred at Dilsukhnagar in February 2013 are the latest terrorist attacks in Hyderabad.[26]

Geography

Topography

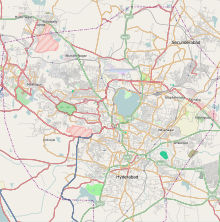

Hyderabad is situated in the north-western part of Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India, located 1,566 kilometres (973 mi) south of Delhi, 699 kilometres (434 mi) southeast of Mumbai, and 570 kilometres (350 mi) north of Bangalore by road.[28] It lies on the banks of the Musi River in the northern part of the Deccan Plateau.[29][30] The city is spread over 650 km2 (250 sq mi), making it one of the largest metropolitan areas in India.[29] Hyderabad, with an average altitude of 1,778 feet (542 m), has a predominantly sloping terrain of grey and pink granite, dotted with small hills; Banjara Hills, at 2,206 feet (672 m), is the highest.[30][31] The city's lakes are often called sagar ("sea"). Hussain Sagar, built in 1562, is near the city centre. Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar are artificial lakes created by dams on the Musi.[30][32] As of 1996, the city had 140 lakes and 834 water tanks (ponds).[33]

Climate

Hyderabad has a tropical wet and dry climate (Köppen Aw) bordering on a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh).[34] The annual mean temperature is 26 °C (78.8 °F); monthly mean temperatures are 21–32 °C (70–90 °F).[35] Summers (March–June) are hot and humid, with average highs in the mid 30s Celsius;[36] maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) between April and June.[35] Winter lasts for only about 2+1⁄2 months, during which the lowest temperature occasionally dips to 10 °C (50 °F) in December and January.[35] May is the hottest month, when daily temperatures range from 26 to 38.8 °C (79 to 102 °F); January, the coldest, has temperatures varying from 14.7 to 28.6 °C (58 to 83 °F).[36] Temperatures in the evenings and mornings are generally cooler because of the city's moderate elevation.

Heavy rain from the south-west summer monsoon falls on Hyderabad between June and September,[37] supplying it with most of its annual rainfall of 812.5 mm (32 in).[36] The highest total monthly rainfall, 181.5 mm (7 in), occurs in September.[36] The heaviest rainfall recorded in a 24-hour period was 241 mm (9 in) on 24 August 2000. The highest temperature ever recorded was 45.5 °C (114 °F) on 2 June 1966, and the lowest was 8 °C (46 °F) on 8 January 1946. The city receives 2,731 hours of sunshine per year; maximum daily sunlight exposure occurs in February.[37][38]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.9 (96.6) |

39.1 (102.4) |

42.2 (108.0) |

43.3 (109.9) |

44.5 (112.1) |

45.5 (113.9) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.5 (97.7) |

36.7 (98.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

45.5 (113.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.6 (83.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.8 (101.8) |

34.4 (93.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

32.0 (89.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

20.0 (67.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 9.2 (0.36) |

10.2 (0.40) |

12.3 (0.48) |

27.2 (1.07) |

34.5 (1.36) |

113.8 (4.48) |

162.0 (6.38) |

203.9 (8.03) |

148.5 (5.85) |

113.9 (4.48) |

19.1 (0.75) |

5.0 (0.20) |

859.6 (33.84) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.3 mm) | 1.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 10.9 | 15.4 | 16.3 | 12.3 | 7.6 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 76.9 |

| Average rainy days | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 9.5 | 11.3 | 8.4 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 49.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 41 | 33 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 52 | 65 | 70 | 67 | 59 | 49 | 44 | 48 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

12 (54) |

13 (55) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

19 (66) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

15 (59) |

13 (55) |

16 (61) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 265.6 | 272.8 | 276.0 | 279.0 | 180.0 | 136.4 | 133.3 | 162.0 | 226.3 | 243.0 | 251.1 | 2,698.3 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.8 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.4 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 11 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department (sun 1971–2000)[39][40][41] Time and Date (dewpoints, 2005-2015)[42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1991–2020)[44] Weather Atlas[45] | |||||||||||||

Administration

Local government

The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) oversees and manages the civic infrastructure of the city's 18 "circles", which together encompass 150 municipal wards. Each ward is represented by a corporator, elected by popular vote. The corporators elect the Mayor, who is the titular head of GHMC; executive powers rest with the Municipal Commissioner, appointed by the Government of Andhra Pradesh. The GHMC carries out the city's infrastructural work such as building and maintenance of roads and drains; town planning including construction regulation; maintenance of municipal markets and parks; solid waste management; the issuing of birth and death certificates; the issuing of trade licences; collection of property tax; and community welfare services such as mother and child healthcare service, pre-school education, and non-formal education.[46] The GHMC was formed in April 2007 by merging the Municipal Corporation of Hyderabad (MCH) with 12 municipalities of the Hyderabad, Ranga Reddy and Medak districts covering a total area of 650 km2 (250 sq mi).[47][48]: 3 In the 2009 municipal election, an alliance of the Indian National Congress and Majlis Ittehadul Muslimeen formed the majority.[49] The Secunderabad Cantonment Board is a civic administration agency overseeing an area of 40.1 km2 (15.5 sq mi),[50]: 93 where there are several military camps.[51]: 2 The Osmania University campus is administered independently by the university authority.[50]: 93

Hyderabad's administrative agencies have varied jurisdictions. The Hyderabad Police area is the smallest, followed in ascending size by Hyderabad district, the GHMC area ("Hyderabad city") and the area under the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA). The HMDA is an apolitical urban planning agency that encompasses the GHMC and its suburbs, extending to 54 mandals in five districts occupying an area of 7,100 km2 (2,700 sq mi).[52] It coordinates the development activities of GHMC and suburban municipalities, and manages the administration of the Hyderabad Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (HMWSSB), the Andhra Pradesh Transmission Corporation, the Andhra Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (APSRTC) and other bodies.[52]

The jurisdiction of the Hyderabad Police Commissionerate is divided into five police zones, each headed by a deputy commissioner.[53] The Hyderabad Traffic Police is headed by a deputy commissioner who reports to the commissioner.[54] In 2012, the Andhra Pradesh Government announced its intention to merge the Hyderabad and Cyberabad Police Commissionerates into a single Greater Hyderabad Police Commissionerate.[55]

As the seat of the Government of Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad is home to the Andhra Pradesh Legislature, the state secretariat and the Andhra Pradesh High Court, as well as to various local government agencies. The Lower City Civil Court and the Metropolitan Criminal Court are under the jurisdiction of the High Court.[56][57]: 1 The GHMC area contains 24 State Legislative Assembly constituencies, which come under 5 constituencies of the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Parliament of India).[47]

Utility services

The HMWSSB regulates rainwater harvesting, water supply and sewerage services.[52] It sources water from several dams located in the suburbs.[58] In 2005 the HMWSSB started operating a 150-kilometre-long (93 mi) water supply pipeline from Nagarjuna Sagar Dam to meet increasing demands.[58] The Andhra Pradesh Central Power Distribution Company manages electricity supply.[52] Firefighting services are provided by the Andhra Pradesh Fire Services department. As of March 2012, the city has 13 fire stations.[59] The state-owned Indian Postal Service has five head post offices and many sub-post offices in Hyderabad; privately run courier services are also available.[30]

Pollution control

Every day, Hyderabad produces around 4,500 metric tonnes of solid waste, which is transported from collection units in Imlibun, Yousufguda and Lower Tank Bund to the dumpsite in Jawaharnagar.[60] The GHMC started the Integrated Solid Waste Management project in 2010 to manage waste disposal.[61] The Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board (APPCB) is the regulatory and screening authority for pollution. Rapid urbanisation and increased economic activity encouraged migration to Hyderabad, which led to increased air pollution, industrial waste, noise pollution and water pollution.[62] The contribution of different sources to air pollution in 2006 was: 20–50% from vehicles, 40–70% from a combination of vehicle discharge and road dust, 10–30% from industrial discharges and 3–10% from the burning of household rubbish.[63] Deaths from atmospheric particulate matter are estimated at 1,700–3,000 each year.[64] The ground water in Hyderabad has a hardness of up to 1000 ppm, around three times higher than is desirable.[65] The region's ground water levels are shrinking, and dams are facing water shortage due to burgeoning population and the consequent increase in demand.[58][66] Inadequately treated effluents from industrial treatment plants are polluting the drinking water sources of the city.[67]

Healthcare

The Andhra Pradesh Vaidya Vidhana Parishad, a department of the state government, administers healthcare in Hyderabad.[68] In 2010–11 the city had 50 government hospitals,[69] 300 private and charity hospitals and 194 nursing homes; together these facilities provide approximately 12,000 hospital beds, less than half of the required 25,000.[70][71] For every 10,000 people in the city, there are 17.6 hospital beds,[72] 9 specialist doctors, 14 nurses and 6 physicians.[71] The city also has about 4,000 individual clinics[73] and 500 medical diagnostic centres.[70] Most residents prefer treatment at private facilities, and only 28% use government facilities, because of their distance, poor quality of care and long waiting times.[74]: 60–61 As of 2012, many new private hospitals of various sizes have opened or are being built.[73] Hyderabad also has outpatient and inpatient facilities that use Unani, homeopathic and Ayurvedic treatments.[75]

According to the 2005 National Family Health Survey, 24% of Hyderabad's households were covered by government health schemes or health insurance—the highest proportion among the cities surveyed.[74]: 4 The city's total fertility rate is 1.8,[74]: 47 Only 61% of children had been provided with all basic vaccines (BCG, measles and full courses of polio and DPT), fewer than in all other surveyed cities except Meerut.[74]: 98 The infant mortality rate was 35 per 1,000 live births, and the mortality rate for children under five was 41 per 1,000 live births.[74]: 97 According to the survey, about a third of women and a quarter of men are overweight or obese, about 49% of children below 5 years are anaemic, and up to 20% of children are underweight.[74]: 44, 55–56 More than 2% of women and 3% of men suffer from diabetes in Hyderabad.[74]: 57

Demographics

Template:India census population

When the GHMC was created in 2007, the area occupied by the municipality increased from 175 km2 (68 sq mi) to 650 km2 (250 sq mi).[29] As a consequence, the population increased by over 87%, from 3,637,483 in the 2001 census to 6,809,970 in the 2011 census, making Hyderabad the fourth most populous city in India.[76][77] Migrants from elsewhere in India constitute 24% of the city population.[51]: 2 The population density is 18,480/km2 (47,900/sq mi).[78] The Hyderabad Urban Agglomeration has a population of 7,749,334, making it the sixth most populous urban agglomeration in the country.[77]

There are 3,500,802 male and 3,309,168 female citizens—a sex ratio of 945 females per 1000 males,[79] higher than the national average of 926 per 1000.[80] Among children aged 0–6 years, 373,794 are boys and 352,022 are girls—a ratio of 942 per 1000.[79] Literacy stands at 82.96% (male 85.96%; female 79.79%), higher than the national average of 74.04%.[81]

Ethnic groups, language and religion

The majority of the residents of Hyderabad, referred to as "Hyderabadi", are Telugu people, followed by Urdu-speaking people and a minority of Marathi, Kannada (including Nawayathi), Marwari, Bengali, Tamil, Malayali, Gujarati, Punjabi and Uttar Pradeshi communities. Among the communities of foreign origin, Yemeni Arabs form the majority, and African Arabs, Armenians, Abyssinians, Iranians, Pathans and Turkish people are also present. The foreign population declined after Hyderabad State became part of the Indian Union, as it lost the patronage of the Nizams.[82]

Telugu is the official language of Hyderabad and Urdu is its second language.[84] The Telugu dialect spoken in Hyderabad is called Telangana, and the Urdu spoken is called Dakhani.[85]: 1869–70 [86] English is also used, particularly among white-collar workers.[87] A significant minority speaks other languages, including Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Kannada and Tamil.[82]

Hindus form the majority of Hyderabad's population. Muslims are present throughout the city and predominate in and around the Old City. There are also Christian, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist and Parsi communities, and iconic temples, mosques and churches can be seen.[88] According to the 2001 census, Hyderabad district's religious make-up was: Hindus (55.41%), Muslims (41.17%), Christians (2.43%), Jains (0.43%), Sikhs (0.29%) and Buddhists (0.02%); 0.23% did not state any religion.[83]

Slums

According to a 2012 report submitted by GHMC to the World Bank, Hyderabad has 1,476 slums with a total population of 1.7 million, of whom 66% live in 985 slums in the "core" of the city (the part that formed Hyderabad before the April 2007 expansion) and the remaining 34% live in 491 in suburban tenements.[89] About 22% of the slum-dwelling households had migrated from different parts of India in the last decade of the 20th century, and 63% claimed to have lived in the slums for over 10 years.[51]: 55 Overall literacy in the slums is 60–80% and female literacy is 52–73%. A third of the slums have basic service connections and 90% have water supply lines. There are 405 government schools, 267 government aided schools, 175 private schools and 528 community halls in the slum areas.[90]: 70

According to a 2008 survey by the Centre for Good Governance, 87.6% of the slum-dwelling households are nuclear families, 18% are very poor, with an income of ₹20,000 (US$240) per annum, 73% live below the poverty line (a standard poverty line recognised by the Andhra Pradesh Government is ₹24,000 (US$290) per annum), 27% of the chief wage earners (CWE) are casual labour and 38% of the CWE are illiterate. About 3.72% of the slum children aged 5–14 do not go to school and 3.17% work as child labour, of whom 64% are boys and 36% are girls. The largest employers of child labour are street shops and construction sites. Among the working children, 35% are engaged in hazardous jobs.[51]: 59

Cityscape

Neighbourhoods

The historic city established by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah on the southern side of the Musi River forms the "Old City", while the "New City" encompasses the urbanised area on the northern banks. The two are connected by many bridges across the river, the oldest of which is Purana Pul (old bridge).[91] Hyderabad is twinned with neighbouring Secunderabad, from which it is separated by Hussain Sagar.

In the southern part of central Hyderabad are many historical and touristic sites, such as the Charminar, the Mecca Masjid, the Salar Jung Museum, the Nizam's museum, the Falaknuma Palace, and the traditional retail corridor comprising Laad Bazaar, Pearls Market and Madina circle. North of the river are hospitals, colleges, major railway stations and business areas such as Begum Bazaar, Koti, Abids, Sultan Bazaar and Moazzam Jahi Market, along with administrative and recreational establishments such as the Reserve Bank of India, the Andhra Pradesh Secretariat, the Hyderabad Mint, the Andhra Pradesh Legislature, the Public Garden, the Nizam Club, the Ravindra Bharathi, the state museum, the Birla Temple and the Birla Planetarium.[92][93][94]

Towards the north of central Hyderabad lie Hussain Sagar, Tank Bund Road, Rani Gunj and the Secunderabad Railway Station.[92] The majority of the city's parks and recreation centres are here, such as Sanjeevaiah Park, Indira Park, Lumbini Park, NTR Gardens, the Buddha statue and Tankbund Park.[27] In the northwest part of the city there are upscale residential areas such as Banjara Hills, Jubilee Hills, Begumpet and Khairatabad. The northern end contains industrial areas such as Sanathnagar, Moosapet, Balanagar, Pathan Cheru and Chanda Nagar. The northeast end is dotted with residential colonies.[92][93][94] The "Cyberabad" area in the southwest and west parts of the city has grown rapidly since the 1990s. It is home to information technology and bio-pharmaceutical companies and to landmarks such as Hyderabad Airport, Osman Sagar, Himayath Sagar and KBR National Park. In the eastern part of the city lie many defence research centres and Ramoji Film City.

Landmarks

Hyderabad’s architecture is primarily known for its heritage buildings constructed during Qutb shahi and Nizam rule, and showcasing the Indo-Islamic architecture with influence of Medieval, Mughal and European styles.[4][97] After the 1908 Musi River flood devastated the city, it was expanded, and civic monuments constructed, particularly during the rule of Mir Osman Ali Khan (the VIIth Nizam). He became known as the maker of modern Hyderabad because of his patronage of architecture.[98][99] In 2012, the government of India declared Hyderabad the first "Best heritage city of India".[100]

The Qutb Shahi architecture of the 16th and early 17th centuries followed the classical Persian model of domes and colossal arches.[101] The oldest surviving Qutb Shahi structure in Hyderabad is the ruins of Golconda fort built in 16th century. The Charminar, Mecca Masjid, Charkaman and Qutb Shahi Tombs are the other existing structures of this period; among these the Charminar has become an icon of the city. Located in the centre of old Hyderabad, it is a square structure with each side 20 metres (66 ft) long and four grand arches each facing a road. At each corner stands an exquisitely designed 56 metres (184 ft) minaret. Granite and lime mortar are the principal materials used in the Qutb shahi structures. Most of the historical Bazaars that still exist were constructed on the street north of Charminar towards Golconda fort. The Charminar, the Qutb Shahi tombs and the Golconda fort are among the monuments of national importance in India; in 2010 the sites were proposed by the Indian government for a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[98][102][103]: 11–18 [104]

Among the oldest surviving examples of Nizam architecture in Hyderabad is the Chowmahalla Palace, which was the royal seat and the largest palace. It showcases a diverse array of architectural styles, from Baroque inside the Harem, to its Neoclassical style royal court. The other palaces built by the Nizams include Falaknuma Palace (inspired by Andrea Palladio villas), Purani Haveli, King Kothi and Bella Vista Palace all of which were built at the peak of the Nizam rule in the 19th century. During Mir Osman Ali Khan's rule, the European styles along with Indo-Islamic became prominent, reflected in Falaknuma Palace and much of the civic monuments such as Hyderabad High Court, Osmania Hospital, Osmania University, Hyderabad and Kachiguda railway stations, State Central Library, City College, Andhra Pradesh Legislature, State Archaeology Museum and Jubilee Hall.[98][101][105][106] Parallel to Nizam's palaces the aristocratic Paigah family constructed hillock villas: Paigah Palace, Asman Garh Palace, Basheer Bagh Palace, Errum Manzil and Spanish Mosque.[103]: 16–17 [107][108]

Economy

Of all the cities in Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad is the largest contributor to the state's gross domestic product (GDP), tax and other revenues.[109] Its $74 billion GDP makes it the fifth-largest contributor city to India's overall GDP.[110] Its per capita annual income in 2011 was ₹44,300 (US$530).[111] As of 2006, the largest employers in the city are the governments of Andhra Pradesh (113,098 employees) and of India (85,155).[112] According to a government survey in 2005, 77% of males and 19% of females in the city were employed.[113] The service industry remains dominant in the city, and 90% of the employed workforce is engaged in this sector.[114]

Hyderabad is known as the "City of Pearls" because of its role in the pearl trade. Until the 18th century, the city was the only global trading centre for large diamonds.[15][115] Industrialisation began under the Nizams in the late 19th century, helped by railway expansion that connected the city with major ports.[116][117] From the 1950s to the 1970s, Indian enterprises were established in the city,[118] such as Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL), National Mineral Development Corporation (NMDC), Bharat Electronics (BE), Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL), Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), Centre for Cellular & Molecular Biology (CCMB), Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD), Andhra Bank (AB) and State Bank of Hyderabad (SBH).[93] The city is home to the Hyderabad Securities formerly known as Hyderabad Stock Exchange (HSE),[119] and houses the regional office of Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).[120] Thus Hyderabad evolved from a traditional manufacturing city to a cosmopolitan industrial service centre.[93] Since the 1990s, the growth of information technology (IT), IT-enabled services, insurance and financial institutions has expanded the service sector, and these primary economic activities have boosted the ancillary sectors of trade and commerce, transport, storage, communication, real estate and retail.[117]

Hyderabad's commercial markets are divided into four sectors: central business districts, sub-central business centres, neighbourhood business centres and local business centres.[121] Several central business districts are spread across the city.[122] Many traditional and historical bazaars are located in the city.[123][124] The Laad Bazaar and nearby markets have shops that sell pearls, diamonds and other traditional ware and cultural antiques.[123] According to a survey by Cushman & Wakefield, Hyderabad's retail industry and traditional markets were growing in 2007.[125]

The establishment of the Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Limited (IDPL), a public sector undertaking, in 1961 was followed over the decades by many national and global companies opening manufacturing and research facilities in the city,[126] contributing to its reputation as "India's pharmaceutical capital" and the "Genome Valley of India".[127] It is a global centre of information technology, for which it is known as Cyberabad (Cyber City).[128][129] During 2008–09, Hyderabad's IT exports reached US$ 4.7 billion,[130] and 22% of the NASSCOM's total membership is from the city.[111] The development of HITEC City, a township with extensive technological infrastructure, prompted multinational companies to establish facilities in Hyderabad.[128] The city is home to more than 1300 IT and ITES firms, including global conglomerates such as Microsoft (operating its largest R&D campus outside the US), Google, IBM, Yahoo!, Dell, Facebook,[51]: 3 [131] and major Indian firms including Mahindra Satyam, Infosys, TCS, Genpact and Wipro.[51]: 3 In 2009 the World Bank Group ranked the city as the second best Indian city for doing business.[132] The city and its suburbs contain the highest number of special economic zones of any Indian city.[111]

Like the rest of India, Hyderabad has a large informal economy that employs 30% of the labour force.[90]: 71 According to a survey published in 2007, it had 40–50,000 street vendors, and their numbers were increasing.[133]: 9 Among the street vendors, 84% are male and 16% female,[134]: 12 and four fifths are "stationary vendors" operating from a fixed pitch, often with their own stall.[134]: 15–16 Most are financed through personal savings; only 8% borrow from moneylenders.[134]: 19 Vendor earnings vary from ₹50 (60¢ US) to ₹800 (US$9.60) per day.[133] Other unorganised economic sectors include dairy, poultry farming, brick manufacturing, casual labour and domestic help. Those involved in the informal economy constitute a major portion of urban poor.[90]: 71

Transport

Public modes of transport such as buses, auto rickshaws and light railways are most commonly used in Hyderabad.[135] Half of the vehicles in 2001 were two-wheelers, 16% cars, 16% auto rickshaws, 9% bicycles and 3% buses.[136]: 61 As of 2012, there are about 77,000 auto rickshaws and 3,800 APSRTC buses.[137] The bus service provided by the APSRTC was estimated to carry 13 million passengers a day in 2005.[138][139] Setwin (Society for Employment Promotion & Training in Twin Cities) operates minibuses in the city.[140] In some parts of the city cycle rickshaws are hired to travel smaller distances.[141]

Traffic congestion is widespread in the city,[142]: 2–3 and roads occupy only 9.5% of the total city area.[50]: 79 The Inner Ring Road, the Outer Ring Road and various interchanges, overpasses and underpasses have been developed to ease the congestion, including the Hyderabad Elevated Expressway which, as of 2008, is the longest flyover in India.[143] In 2001 it was reported that 40% of accidents are due to poor facilities for pedestrians.[135][136]: 63 Maximum speed limits within the city are 50 km/h (31 mph) for two-wheelers and cars, 35 km/h (22 mph) for auto rickshaws and 40 km/h (25 mph) for light commercial vehicles and buses.[144]

Three National Highways pass through the city: NH-7, NH-9 and NH-202. Five state highways, SH-1, SH-2, SH-4, SH-5 and SH-6, either begin at or pass through Hyderabad.[136]: 58 The Mahatma Gandhi Bus Station in the city centre is the main bus station.[145] The Secunderabad Railway Station is the headquarters of the South Central Railway zone of Indian Railways, and the largest station in Hyderabad. Other major railway stations in Hyderabad are Hyderabad Deccan Station, Kachiguda Railway Station and Begumpet Railway Station.[146] Hyderabad's light rail transportation system, known as the Multi-Modal Transport System, is used by over 150,000 passengers daily.[147] Hyderabad Metro, a rapid transit system, is under construction and is scheduled to operate three lines by 2014.[148] Rajiv Gandhi International Airport (RGAI) (IATA: HYD, ICAO: VOHS) was opened in 2008, replacing Begumpet Airport.[149] In 2011, Airports Council International, an autonomous body representing the world's airports, judged RGAI the world's best airport in the 5–15 million passenger category and the world's fifth best airport for Airport service quality.[150]

Culture

Hyderabad emerged as the foremost centre of culture in India, when the Mughal Empire in Delhi declined in 1857 AD. The migration of performing artists to the city particularly from the north and west of the Indian sub continent, under the patronage of the Nizam, enriched the cultural milieu.[151] The city is noted for the mingling of North and South Indian linguistic and cultural traits and for the coexistence of Hindu and Muslim traditions.[152][153]: viii Telugu and Urdu are the languages most commonly spoken.[154] Traditional Hyderabadi garb is Sherwani and Kurta–Paijama for men and Khara Dupatta and Salwar kameez for women.[155][156][157] Muslim women commonly wear burqas and hijabs in public.[158] Most youth wear western clothing.[159] Festivals celebrated in Hyderabad include Ganesh Chaturthi, Diwali, Bonalu, Bathukamma, Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.

Literature

Hyderabad received royal patronage for arts, literature and architecture from Qutb Shahi rulers and Nizams; this attracted artists and men of letters from different parts of the world. The resulting multi-ethnic settlements popularised cultural events such as mushairas (poetic symposia).[160] The Qutb Shahi dynasty patronised the growth of Deccani Urdu literature; the Deccani Masnavi and Diwan (collection of poems) composed during this period are among the earliest available manuscripts in Urdu.[161] The reign of the Nizams saw many literary reforms and the introduction of Urdu as a language of court, administration and education.[162] In 1824, a collection of Urdu Ghazals (a specific poetic form) named Gulzar-e-Mahlaqa, authored by Mah Laqa Bai—the first female Urdu poet—was published in Hyderabad.[163] The Hyderabad Literary Festival, held since 2010, is an annual event that showcases the city's literary and cultural creativity.[164] Organisations engaged in research into and promotion of literature include the Sahitya Akademi, the Urdu Academy, the Telugu Academy, the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language, the Comparative Literature Association of India, and the Andhra Saraswata Parishad. The State Central Library, established in 1891, is the largest public library in the state.[165] Other major libraries are the Sri Krishna Devaraya Andhra Bhasha Nilayam, the British Library and the Sundarayya Vignana Kendram.[166]

Music, performing arts and films

South Indian music and dances such as the Kuchipudi and Kathakali styles are popular in the Deccan region. North Indian music and dance gained popularity during the Mughals and Nizam rule.[167] It became a tradition among the nobility in the princely state of Hyderabad to keep courtesans and to learn singing, poetry and classical dance from them.[168] This gave rise to certain styles of court music, dance and poetry. Taramati in the 17th century[169] and Mah Laqa Bai in the 18th and 19th centuries were notable among such courtesans.[168] Besides western and Indian popular music genres such as filmi music, the residents of Hyderabad play city-based marfa music, especially at weddings, festivals and other celebratory events.[170] The state government organises the Golconda Music and Dance Festival, the Taramati Music Festival and the Premavathi Dance Festival.[171] Though the city is not particularly noted for theatre and drama,[172] the state government promotes theatre with multiple programmes and festivals.[173][174] The Ravindra Bharati, Shilpakala Vedika and Lalithakala Thoranam are auditoria for theatre and performing arts in the city. Numaish is a popular annual exhibition of local and national consumer products.[175] The city is home to the Telugu film industry, popularly known as Tollywood.[176] As of 2012, Tollywood is second only to Bollywood in number of films produced in India.[177] Since 2005, films in local Hyderabadi dialect have gained in popularity.[178] The city hosts the annual International Children's Film Festival and the Hyderabad International Film Festival.[179] In 2005, Guinness World Records declared Ramoji Film City to be the world's largest film studio.[180]

Art and handicraft

The Golconda and Hyderabad styles are branches of Deccani painting.[181] Developed during the 16th century, the Golconda style is a native style blending foreign techniques, bearing some similarity to the Vijayanagara paintings of neighbouring Mysore. A significant use of luminous gold and white colours is generally found in the Golconda style.[182] The Hyderabad style originated in the early 17th century under the Nizams. Highly influenced by Mughal painting, this style makes use of bright colours and mostly depicts regional landscape, culture, costumes and jewellery.[181]

A metalware handicraft known as Bidri ware was popularised in the region in the 18th century. Bidri ware is a Geographical Indication (GI) tagged craft of India.[98][183] Kalamkari, a hand-painted or block-printed cotton textile, is popular in the city.[184] Hyderabad's museums include the Salar Jung Museum (housing "one of the largest one-man-collections in the world"[185]), the AP State Archaeology Museum, the Nizam Museum, the City Museum and the Birla Science Museum, which contains a planetarium.[186]

Cuisine

Hyderabadi cuisine comprises a broad repertoire of rice, wheat and meat dishes and the skilled use of various spices.[187] Hyderabadi biryani and Hyderabadi haleem, with their blend of Mughlai and Arab cuisines,[188] have become iconic dishes of India.[189] Hyderabadi cuisine is highly influenced by Mughlai and to some extent by French,[190] Arabic, Turkish, Iranian and native Telugu and Marathwada cuisines.[157][188] Other popular native dishes include nihari, chakna, baghara baingan and the desserts qubani ka meetha, double ka meetha and kaddu ki kheer (a sweet porridge made with sweet gourd).[157][191]

Media

One of the earliest newspapers to be published in Hyderabad was The Deccan Times, which was established in the 1780s.[192] The major Telugu dailies published in Hyderabad are Eenadu, Sakshi and Andhra Jyothy, the major English papers are The Times of India, The Hindu and The Deccan Chronicle,[193] and the major Urdu papers include The Siasat Daily, The Munsif Daily and Etemaad. Many coffee table magazines, professional magazines and research journals are regularly published there.[194] The Secunderabad Cantonment Board established the first radio station in Hyderabad State around 1919. Deccan Radio was the first radio station in the city to broadcast to the public. It went on air on 3 February 1935.[195] In 2000, radio stations were permitted to broadcast in FM;[196] the available channels included All India Radio, Radio Mirchi, Radio City and Big FM.[197]

Television broadcasting in Hyderabad began in 1974 with the launch of Doordarshan, the Government of India's public service broadcaster,[198] which transmits two free-to-air terrestrial television channels and one satellite channel. Private satellite channels started in July 1992 with the launch of Star TV.[199] Satellite TV channels are accessible via cable subscription, direct-broadcast satellite services or internet-based television.[196][200] Hyderabad's first dial-up Internet access became available in the early 1990s and was limited to software development companies.[201] The first public internet access service began in 1995, and the first private sector Internet service provider (ISP) started operating in 1998.[202]

Education

Schools in Hyderabad are affiliated to the Central Board of Secondary Education, the Secondary School Certificate[203] or the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education, and they may be run by government or by private entities such as local governing bodies, individuals, missionaries or other agencies. Around two-thirds of pupils go to private schools.[204] Languages of instruction include English, Hindi, Urdu[205] and Telugu. Schools follow the "10+2+3" plan. After completing secondary education, students have to enroll in schools or junior colleges with a higher secondary facility. Admission to professional graduation colleges in Hyderbad is through Engineering Agricultural and Medical Common Entrance Test (EAM-CET). Most colleges are affiliated with either Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University or Osmania University.[206]

There are 13 universities in Hyderabad: two private universities, two deemed universities, six state universities and three central universities. The central universities are the University of Hyderabad,[207] Maulana Azad National Urdu University and the English and Foreign Languages University.[208] Osmania University, established in 1918, was the first university in Hyderabad. As of 2012, it is India's second most popular destination for international students.[209] The Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Open University, established in 1982, is the first distance-learning open university in India.[210]

Notable business and management schools in Hyderabad include the Indian School of Business,[211] National Institute of Rural Development,[212] and the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of India.[213] Institutes of national importance include the Institute of Public Enterprise, the Administrative Staff College of India, and the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy. Hyderabad has five major medical schools—Osmania Medical College, Gandhi Medical College, Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences, Deccan College of Medical Sciences and Shadan Institute Of Medical Sciences[214]—and many affiliated teaching hospitals. The Government Nizamia Tibbi College, is a college of unani medicine.[215]

Hyderabad is also a major centre for biomedical, biotechnology and pharmaceutical study and research;[216] the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research is located here.[217] The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics and the Acharya N. G. Ranga Agricultural University are notable agricultural engineering institutes. Many of India's leading technical and engineering schools are in Hyderabad, including the International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad (IIITH), the Birla Institute of Technology & Science, and the Indian Institute Of Technology (IITH). Schools of fashion design in the city include Raffles Millennium International, NIFT Hyderabad and Wigan and Leigh College.

Sports

Cricket and association football[218] are the most popular sports in Hyderabad. The city has hosted national and international sports events such as the 2002 National Games of India, the 2003 Afro-Asian Games, the 2004 AP Tourism Hyderabad Open women's tennis tournament, the 2007 Military World Games, the 2009 World Badminton Championships and the 2009 IBSF World Snooker Championship. The Swarnandhra Pradesh Sports Complex is a venue for field hockey, and the G.M.C. Balayogi Stadium in Gachibowli serves as a venue for athletics and football.[219]

The Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium and the Rajiv Gandhi International Cricket Stadium host cricket matches;[220] the latter serves as the home ground of Hyderabad Cricket Association. Hyderabad has been the venue of many international cricket matches, including matches in the 1987 and the 1996 Cricket World Cups. The Hyderabad cricket team represents the city in the Ranji Trophy—a first-class cricket tournament among India's states and cities. Hyderabad is home to the Indian Premier League franchise Sunrisers Hyderabad formerly known as Deccan Chargers which won the 2009 Indian Premier League held in South Africa.[221]

During the British rule, Secunderabad was a well-known sporting centre, and had many parade and polo grounds, race course and other sporting facilities.[222]: 18 The city houses many elite clubs formed by the Nizams and the British, such as the Secunderabad Club, the Nizam Club and the Hyderabad Race Club, which is known for its horse racing,[223] especially the annual Deccan derby.[224] The Andhra Pradesh Motor Sports Club organises popular events such as the Deccan 1/4 Mile Drag,[225] TSD Rallies and 4x4 off-road rallying.[226] The Hyderabad Golf Club has an eighteen-hole golf course.[227] Notable international sportspeople from Hyderabad include: cricketers Ghulam Ahmed, M. L. Jaisimha, Mohammed Azharuddin, V. V. S. Laxman, Venkatapathy Raju, Shivlal Yadav, Arshad Ayub and Noel David; football players Syed Abdul Rahim, Syed Nayeemuddin and Shabbir Ali;[228] tennis player Sania Mirza; badminton players S. M. Arif, Pullela Gopichand, Saina Nehwal, Jwala Gutta and Chetan Anand; hockey players Syed Mohammad Hadi and Mukesh Kumar; and bodybuilder Mir Mohtesham Ali Khan.

Sister Cities

| City | Geographical location | Nation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brisbane | Queensland | [229] | |

| Ipswich | Queensland | [229] | |

| Dubai | Dubai | [230] | |

| Miyoshi | Hiroshima | [231] | |

| Riverside | California | [232] | |

| Indianapolis | Indiana | [233] | |

| San Diego | California | [234] |

See also

- List of tallest buildings in Hyderabad

- List of million-plus cities in India

- List of people from Hyderabad

References

- ^ a b Everett-Heath, John (2005). Concise dictionary of world place names. Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-860537-9. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b McCann, Michael W. (1994). Rights at work: pay equity reform and the politics of legal mobilization. University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-226-55571-2.

- The march of India. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 1959. p. 89. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Khan, Masud Ḥusain (1996). Mohammad Quli Qutb Shah. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-81-260-0233-7. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Reddy, Gayatri (2005). With respect to sex: negotiating hijra identity in south India. University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-226-70755-5.

- Kakar, Sudhir (1996). The colors of violence: cultural identities, religion, and conflict. University of Chicago Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-226-42284-4.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the world: origins and meanings of the names for 6,600 countries, cities, territories, natural features and historic sites. McFarland. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 0-415-06084-2.

- ^ "Hyderabad's history could date back to 500 BC". GHMC. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Ramachandran, Priya (4 February 2012). "Golconda fort: Hyderabad's time machine". The Siasat Daily. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Kolluru, Suryanarayana (1993). Inscriptions of the minor Chalukya dynasties of Andhra Pradesh. Mittal Publications. p. 1. ISBN 81-7099-216-8.

- ^ a b c Sardar, Marika (2007). Golconda through time: a mirror of the evolving Deccan. ProQuest. pp. 19–41. ISBN 0-549-10119-5.

- Jaisi, Sidq (2004). The nocturnal court: life of a prince of Hyderabad. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-19-566605-2.

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1976). A history of south India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008). Historical dictionary of medieval India. The Scarecrow Press. p. 85 and 141. ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8.

- ^ Ghose, Archana Khare (29 February 2012). "Heritage Golconda diamond up for auction at Sotheby's". The Times of India. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1996). Historical dictionary of the British empire. Greenwood Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-313-27917-1.

- ^ Aleem, Shamim; Aleem, M. Aabdul, eds. (1984). Developments in administration under H.E.H. the Nizam VII. Osmania University Press. p. 243. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Bansal, Sunita Pant (2005). Encyclopedia of India. Smriti Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-81-87967-71-2.

- ^ a b c d e Richards, J. F. (1975). "The Hyderabad Karnatik, 1687–1707". Modern Asian Studies. 9 (2). Cambridge University Press: 241–260. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00004996. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ a b Hansen, Waldemar (1972). The Peacock throne: the drama of Mogul India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 168 and 471. ISBN 81-208-0225-X.

- ^ a b c d e Ikram, S.M. (1964). "A century of political decline: 1707–1803". In Embree, Ainslie T (ed.). Muslim civilization in India. Columbia University. ISBN 978-0-231-02580-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)- Rao, Sushil (11 December 2009). "Testing time again for the pearl of Deccan". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Regani, Sarojini (1988). Nizam-British relations, 1724–1857. Concept Publishing. pp. 130–150. ISBN 81-7022-195-1.

- Farooqui, Salma Ahmed (2011). A comprehensive history of medieval India. Dorling Kindersley. p. 346. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- Malleson, George Bruce (2005). An historical sketch of the native states of India in subsidiary alliance with the British government. Asian Education Services. pp. 280–292. ISBN 978-81-206-1971-5.

- Townsend, Meredith (2010). The annals of Indian administration, Volume 14. BiblioBazaar. p. 467. ISBN 978-1-145-42314-5.

- ^ Venkateshwarlu, K (17 September 2004). "Momentous day for lovers of freedom, democracy". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Sathees, P.V.; Pimbert, Michel; The DDS Community Media Trust (2008). Affirming life and diversity. Pragati Offset. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-84369-674-2.

- ^ "Ambedkar for Hyderabad state (telangana) as second capital of India". Ambedkar organization. 1955. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ "Rashtrapati bhavan:presidential retreats". presidentofindia.nic. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Vohra, J.N. (8 July 2007). "Palaces of the President". The Tribune. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Falzon, Mark-Anthony (2009). Multi-sited ethnography: theory, praxis and locality in contemporary research. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-7546-9144-0.

- ^ "How Telangana movement has sparked political turf war in Andhra". Rediff.com. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Timeline:history of blasts in Hyderabad". First Post (India). 22 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "At least 13 killed in bombing, riots at mosque in India". CBC News. 18 May 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ "Hyderabad bomb blasts:two deadly explosions leave terror cloud over India". Time (magazine). 21 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ a b Kodarkar, Mohan. "Implementing the ecosystem approach to preserve the ecological integrity of urban lakes: the case of lake Hussain sagar, Hyderabad, India" (PDF). Ecosystem approach for conservation of lake Hussainsagar. International Lake Environment Committee Foundation. p. 3. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Hussain sagar stink is not a bother". The Times of India. 2 February 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Google (6 January 2013). "Hyderabad" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Greater Hyderabad municipal corporation". Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC). Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Physical Feature" (PDF). AP Government. 2002. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Hyderabad geography". JNTU. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Water sources and water supply" (PDF). rainwaterharvesting.org. 2005. p. 2. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Singh, Sreoshi (2010). "Water security in peri-urban south Asia" (PDF). South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Climate and food security. International Rice Research Institute. 1987. p. 348. ISBN 978-971-10-4210-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)- Norman, Michael John Thornley; Pearson, C.J; Searle, P.G.E (1995). The ecology of tropical food crops. Cambridge University Press. pp. 249–251. ISBN 978-0-521-41062-5.

- ^ a b c "Weatherbase entry for Hyderabad". Canty and Associates LLC. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Hyderabad". India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b Yimene, Ababu Minda (2004). An African Indian community in Hyderabad. Cuvillier Verlag. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-3-86537-206-2.

- ^ "Historical weather for Hyderabad, India". Weatherbase. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ "Station: Hyderabad (A) Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 331–332. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Table 3 Monthly mean duration of Sun Shine (hours) at different locations in India" (PDF). Daily Normals of Global & Diffuse Radiation (1971–2000). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Hyderabad, Telangana, India". Time and Date. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Climatological Tables 1991-2020" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Normals Data: Hyderabad Airport - India Latitude: 17.45°N Longitude: 78.47°E Height: 530 (m)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Climate and monthly weather forecast Hyderabad, India". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Citizen's charter". GHMC. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b "GHMC polls: all set for the d-day". The Hindu. 22 November 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Ramachandraia, C (2009). "Drinking water: issues in access and equity" (PDF). jointactionforwater.org. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "Karthika not in a hurry to hand over mayor baton to MIM". The Times of India. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Exploring urban growth management in three developing country cities" (PDF). World Bank. 15 June 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Survey of child labour in slums of Hyderabad: final report" (PDF). Center for Good Governance, Hyderabad. 17 December 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Welcome to HMDA". Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "About us". Hyderabad City Police. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Buddi, Mahesh (27 January 2012). "Why compulsory helmet rule not being implemented in city". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Hyderabad & Cyberabad police commissionerates to be merged". NDTV. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Heritage buildings". Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage. 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "India" (PDF). Redress (charitable organisation). 2002. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b c "If Singur, Manjira dry up, there's Krishna". The Times of India. 11 February 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Fire stations inadequate". CNN-IBN. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Twin festivals pile more garbage load on GHMC". The Hindu. 3 September 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Waste management project gets nod". The Times of India. 18 January 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Guttikunda, Sarath (March 2008). "Co-benefits analysis of air pollution and GHG emissions for Hyderabad,India" (PDF). Integrated Environmental Strategies Program. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Gurjar, Bhola R.; Molina, Luisa T.; Ojha, Chandra S.P., eds. (2010). Air pollution:health and environmental impacts. Taylor and Francis. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-4398-0963-1.

- ^ "50 research scholars to study pollution". CNN-IBN. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "Be a pal and stop polluting". The Deccan Chronicle. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Anjaneyulu, Y.; Jayakumar, I.; Hima Bindu, V.; Sagareswar, G.; Mukunda Rao, P.V.; Rambabu, N.; Ramani, K.V. (2005). "Use of multi-objective air pollution monitoring sites and online air pollution monitoring system for total health risk assessment in Hyderabad, India". International journal of environmental research and public health. 2 (2): 343–354. doi:10.3390/ijerph2005020021. PMID 16705838. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ "Ground water in city unfit for use". The Deccan Chronicle. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "City stares at water scarcity". The Times of India. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Chunduri, Mridula (29 November 2003). "Manjira faces pollution threat". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Kennedy, Loraine; Duggal, Ravi; Lama-Rewal, Stephanie Tawa (2009). "7: Assessing urban governance through the prism of healthcare services in Delhi, Hyderabad and Mumbai". In Ruet, Joel; Lama-Rewal, Stephanie Tawa (eds.). Governing India's metropolises: case studies of four cities. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-55148-9.

- ^ "Government hospitals". GHMC. 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ a b Bhargava, Gopal K.; Bhatt, S.C. (2006). Land and people of Indian states and union territories.(2 Andhra Pradesh). Kalpaz Publication. p. 312. ISBN 81-7835-358-X.

- ^ a b "Hyderabad hospital report". Northbridge Capital. 2010. p. 8. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ As of 2011 census city population is (6809970) and available hospital beds are (12000) which gives the derived rate

- ^ a b Gopal, M.Sai (18 January 2012). "Healthcare sector takes a leap in city". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gupta, Kamla; Arnold, Fred; Lhungdim, H. (2009). "Health and living conditions in eight Indian cities" (PDF). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005–06. International Institute for Population Sciences. Retrieved 13 June 2012. The cities surveyed were Delhi, Meerut, Kolkata, Indore, Mumbai, Nagpur, Chennai and Hyderabad.

- ^ "Ayush department". Government of Andhra Pradesh. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

greater Hyderabadwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Urban agglomerations/cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Government of India. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Hyderabad district records highest literacy rate". The Siasat Daily. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Sex ratio goes up in state". The Times of India. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Hyderabad (greater Hyderabad) city". Census of India, 2011. 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Urban sex ratio below national mark". The Times of India. 21 September 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Henry, Nikhila (23 May 2011). "AP slips further in national literacy ratings". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ a b Krank, Sabrina (2007). "Cultural, spatial and socio-economic fragmentation in the Indian megacity Hyderabad" (PDF). Irmgard Coninx Foundation. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Freitag, Ulrike; Clarence-Smith, W.G. (1997). Hadhrami traders, scholars, and statesmen in the Indian ocean, 1750s–1960s. Brill Publishers. pp. 77–81. ISBN 90-04-10771-1.

- Ifthekhar, J.S. (10 June 2012). "Hyderabad appeal endures". The Hindu. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Census of India – socio-cultural aspects". Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 23 September 2012. On this page, select the "State" radio button, select "Andhra Pradesh" from the drop-down that appears, and click "Submit". When a new page appears, select the "District" radio button, select "Hyderabad" from the new drop-down, and again click "Submit". The new page displayed is Hyderabad's religious make-up.

- ^ "Name doesnt sound as well in other languages!". CNN-IBN. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world. Vol. 4. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32384-4.

- ^ Austin, Peter K (2008). 1000 languages: living, endangered, and lost. University of California Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-520-25560-9.

- ^ "MCH plans citizens' charter in Telugu, Urdu". The Times of India. 1 May 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Khan, Masood Ali (16–31 August 2004). "Muslim population in AP". The Milli Gazette. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Hyderabad: an expat survival guide. Chillibreeze. 2007. p. 21. ISBN 978-81-904055-5-3.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/19472498.2011.577568, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/19472498.2011.577568instead.

- ^ "World bank team visits Hyderabad slums". The Times of India. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ a b c "Basic services to the urban poor" (PDF). City development plan. Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Puranapul 'rented' out to vendors by extortionist". The Deccan Chronicle. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Alam, Shah Manzoor; Reddy, A. Geeta; Markandey, Kalpana (2011). Urban growth theories and settlement systems of India. Concept Publishing. pp. 79–99. ISBN 978-81-8069-739-5.

- ^ a b c d Rao, Nirmala (2007). Cities in transition. Routledge. pp. 117–140. ISBN 0-203-39115-2.

- ^ a b Gopi, K.N (1978). Process of urban fringe development:a model. Concept Publishing. pp. 13–17. ISBN 978-81-7022-017-6.

- Nath, Viswambhar; Aggarwal, Surinder K (2007). Urbanization, urban development, and metropolitan cities in India. Concept Publishing. pp. 375–380. ISBN 81-8069-412-7.

- Alam, Shah Manzoor; Khan, Fatima Ali (1987). Poverty in metropolitan cities. Concept Publishing. pp. 139–157.

- ^ "Refurbished Garden Tomb of Mah Laqa Bai Inaugurated by Consul General". Consulate General of the United States, Hyderabad. 6 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Mah Laqa Bai's tomb restored, to be reopened on March 6". The Times of India. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Burton-Page, John; Michell, George (2008). Indian Islamic architecture: forms and typologies, sites and monuments. Brill Publishers. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-90-04-16339-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2009). The grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture, volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 179 and 286. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Architecture of Hyderabad during the CIB period". aponline.gov.in. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Heritage award for Hyderabad raises many eyebrows". The Times of India. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b Michell, George (1987). The new Cambridge history of India, volumes 1–7. Cambridge University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 0-521-56321-6.

- "Jubilee hall a masterpiece of Asaf Jahi architecture". The Siasat Daily. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "The Qutb Shahi monuments of Hyderabad Golconda Fort, Qutb Shahi tombs, Charminar". UNESCO World Heritage Site. 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ a b Tourist guide to Andhra Pradesh. Sura Books. 2006. ISBN 978-81-74-78176-5. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Qutb Shahi style (mainly in and around Hyderabad city)". aponline.gov.in. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "UNESCO Asia-Pacific heritage awards for culture heritage conservation". UNESCO. 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Palaces of the Nizam: Asaf Jahi style (mainly in and around Hyderabad city)". aponline.gov.in. 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Structure so pure". The Hindu. 31 December 2003. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "The Paigah Palaces (Hyderabad city)". aponline.gov.in. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "India's 25 most competitive cities". Rediff.com. 10 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Jafri, Syed Amin (20 February 2012). "Civic infra bodies get a raw deal in budget". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Sat 3 Nov, 2012, 8:24 PM IST - India Markets closed (28 September 2012). "India's top 15 cities with the highest GDP Photos | Pictures - Yahoo! India Finance". In.finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sivaramakrishnan, K.C. (12 July 2011). "Heat on Hyderabad". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Employee census 2006". Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Andhra Pradesh Government. 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Census of central government employees" (PDF). Ministry of Labour, Government of India. 2003. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ "Employment-unemployment situation in million plus cities of India" (PDF). Delhi Government. 2005: 15. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Country briefing:India–economy". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ de Bruyn, Pippa; Bain, Keith; Allardice, David; Joshi, Shonar (2010). Frommer's India. Wiley Publishing. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-470-55610-8.

- "Hyderabad in NYT 2011 list of must see places". The Times of India. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Other Albion CX19". Albion CX19 restoration project. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b Economy, population and urban sprawl (PDF). Urban population, development and environment dynamics in developing countries. 13 June 2007. pp. 7–19. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Bharadwaj Chand, Swati (14 November 2011). "Brand Hyderabad loss of gloss?". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Laskar, Anirudh (28 January 2013). "Sebi allows exit of Hyderabad stock exchange". Mint (newspaper). Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Sebi opens local office in the city". The Times of India. 26 February 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Scott, Peter (2009). Geography and retailing. Rutgers University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-202-30946-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bharadwaj-Chand, Swati (6 May 2012). "Despite Telangana heat, city's information technology cup brimming over: report". The Times of India. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Mathew, Dennis Marcus (23 July 2005). "Will the real central hub stand up?". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ a b Kumar, Abhijit Dev (22 February 2008). "Laad bazaar traders cry foul". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- Abram, David; Edwards, Nick; Ford, Mike (1982). The rough guide to south India. The Penguin Group. p. 553. ISBN 1-84353-103-8.

- ^ Venkateshwarlu, K. (10 March 2004). "Glory of the gates". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Hyderabad, Chennai & Bangalore witness high rental growth: retail survey". the Hindu Business Line. 16 November 2001. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth (2011). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica educational publishing. p. 188. ISBN 9781615302024. *Felker, Greg; Chaudhuri, Shekhar; György, Katalin (1997). The pharmaceutical industry in India and Hungary. World Bank Publications. p. 9-10. ISSN 0253-7494.

- ^ "Hyderabad: India's genome valley". Rediff.com. 30 November 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Osborne, Alistair (25 January 2009). "Hyderabad is a hot destination for Walsh". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "Job market booming overseas for many American companies". Huffington Post. 28 December 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ a b Roy, Ananya; Aihwa, Ong (2011). Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global. John Wiley & Sons. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-4051-9277-4.

- ^ "An Amazon shot for city". The Times of India. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Chary, Manish Telikicherla (2009). India:nation on the move: an overview of India's people, culture, history, economy, IT industry, and more. iUniverse.com. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-1-4401-1635-3.

- ^ "Brand Hyderabad, takes a hit in Indian unrest". The Daily Telegraph. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Prasso, Sheridan (23 October 2007). "Tour Google India". CNN. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- "The top five cities". Business Today. 27 August 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- "Our office locations". Microsoft. 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ "Ease of doing business in Hyderabad – India (2009)". World Bank Group. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ a b Wipper, Marlis; Dittrich, christoph (2007). "Urban street food vendors in the food provisioning system of Hyderabad" (PDF). Analysis and action for sustainable development of Hyderabad. Humboldt University of Berlin. pp. 9–25. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Bhowmik, Sharit K.; Saha, Debdulal (2012). "Street vending in ten cities in India" (PDF). Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Executive summary of detailed project report" (PDF). Government of Andhra Pradesh. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "Municipal infrastructure" (PDF). Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "AC buses are RTC's white elephants". Asian Age. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "20,000 more autos to hit Hyderabad roads". CNN-IBN. 6 September 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "APSRTC". 31 July 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ A major frota de onibus. Guinness World Records. 2005. p. 143. ISBN 85-00-01522-5.