Cannabidiol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sativex (with THC), Epidiolex |

| Other names | CBD, cannabidiolum, (−)-cannabidiol[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a618051 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Inhalation (smoking, vaping), buccal (aerosol spray), oral (solution)[2][3] |

| Drug class | Cannabinoid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | • Oral: 13–19%[4] • Inhaled: 31% (11–45%)[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 18–32 hours[6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.215.986 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

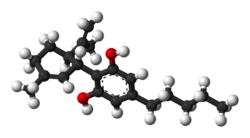

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.464 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 66 °C (151 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a phytocannabinoid discovered in 1940. It is one of 113 identified cannabinoids in cannabis plants and accounts for up to 40% of the plant's extract.[7] As of 2019, clinical research on cannabidiol included studies of anxiety, cognition, movement disorders, and pain, but there is insufficient, high-quality evidence that it is effective for these conditions.[8][9]

Cannabidiol can be taken into the body in multiple ways, including by inhalation of cannabis smoke or vapor, as an aerosol spray into the cheek, and by mouth. It may be supplied as CBD oil containing only CBD as the active ingredient (no included tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or terpenes), a full-plant CBD-dominant hemp extract oil, capsules, dried cannabis, or as a prescription liquid solution.[3][9] CBD does not have the same psychoactivity as THC,[10][11] and may change the effects of THC on the body if both are present.[7][10][12][13] As of 2018[update], the mechanism of action for its putative biological effects has not been determined.[10][12]

In the United States, the cannabidiol drug Epidiolex was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the treatment of two epilepsy disorders.[14] Since cannabis is a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States,[15] other CBD formulations remain illegal to prescribe for medical use or to use as an ingredient in foods or dietary supplements.[16]

Medical uses

Epilepsy

In 2018, CBD was FDA-approved (trade name Epidiolex) for the treatment of two forms of treatment-resistant epilepsy: Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in children with refractory epilepsy.[17][18][19] The recommended daily dose of Epidiolex is 10 mg per kg body weight per day in epileptic children 2-5 years old.[3] While Epidiolex treatment is generally well tolerated, it is associated with minor adverse effects, such as gastrointestinal upset, decreased appetite, sleepiness and lethargy, and poor sleep quality.[17][18][19]

Other uses

Research on other uses for CBD includes several neurological disorders, but the findings have not been confirmed to establish such uses in clinical practice.[6][8][9][10][20][21][22] In October 2019, the FDA issued an advisory warning that the effects of CBD during pregnancy or breastfeeding are unknown, indicating that the safety, doses, interactions with other drugs or foods, and side effects of CBD are not clinically defined, and may pose a risk to the mother and infant.[23]

Side effects

Research indicates that cannabidiol may reduce adverse effects of THC, particularly those causing intoxication and sedation, but only at high doses.[24] Safety studies of cannabidiol showed it is well tolerated, but may cause tiredness, diarrhea, or changes in appetite as common adverse effects.[25] Epidiolex documentation lists sleepiness, insomnia and poor quality sleep, decreased appetite, diarrhea, and fatigue.[3]

Potential interactions

Laboratory evidence indicated that cannabidiol may reduce THC clearance, increasing plasma concentrations which may raise THC availability to receptors and enhance its effect in a dose-dependent manner.[26][27] In vitro, cannabidiol inhibited receptors affecting the activity of voltage-dependent sodium and potassium channels, which may affect neural activity.[28] A small clinical trial reported that CBD partially inhibited the CYP2C-catalyzed hydroxylation of THC to 11-OH-THC.[29] Little is known about potential drug interactions, but CBD mediates a decrease in clobazam metabolism.[30]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Cannabidiol has low affinity for the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors,[31][32] although it can act as an antagonist of CB1/CB2 agonists despite this low affinity.[32] Cannabidiol may be an antagonist of GPR55, a G protein-coupled receptor and putative cannabinoid receptor that is expressed in the caudate nucleus and putamen in the brain.[33] It also may act as an inverse agonist of GPR3, GPR6, and GPR12.[34] CBD has been shown to act as a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist.[35] It is an allosteric modulator of the μ- and δ-opioid receptors as well.[36] The pharmacological effects of CBD may involve PPARγ agonism and intracellular calcium release.[7]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of CBD is approximately 6% in humans, while its bioavailability via inhalation is 11 to 45% (mean 31%).[4][5] The elimination half-life of CBD is 18–32 hours.[6] Cannabidiol is metabolized in the liver as well as in the intestines by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 enzymes, and UGT1A7, UGT1A9, and UGT2B7 isoforms.[3] CBD may have a wide margin in dosing.[21]

Pharmaceutical preparations

Nabiximols (brand name Sativex), a patented medicine containing CBD and THC in equal proportions, was approved by Health Canada in 2005 to treat central neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis, and in 2007 for cancer-related pain.[37] In New Zealand, Sativex is "approved for use as an add-on treatment for symptom improvement in people with moderate to severe spasticity due to multiple sclerosis who have not responded adequately to other anti-spasticity medication."[38]

Epidiolex is an orally administered cannabidiol solution. It was approved in 2018 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of two rare forms of childhood epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.[14][16]

Chemistry

Cannabidiol is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents such as pentane. At room temperature, it is a colorless crystalline solid.[39] In strongly basic media and the presence of air, it is oxidized to a quinone.[40] Under acidic conditions it cyclizes to THC,[41] which also occurs during pyrolysis (smoking).[42] The synthesis of cannabidiol has been accomplished by several research groups.[43][44][45]

Biosynthesis

Cannabis produces CBD-carboxylic acid through the same metabolic pathway as THC, until the next to last step, where CBDA synthase performs catalysis instead of THCA synthase.[47]

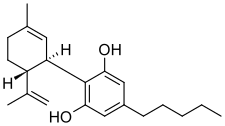

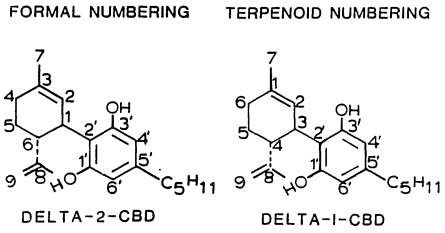

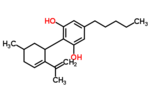

Isomerism

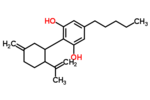

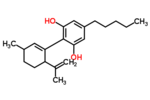

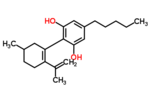

| Formal numbering | Terpenoid numbering | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | Structure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short name | Chiral centers | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers | ||||

| Δ5-Cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-5-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ4-Cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ4-Cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-4-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ5-Cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 4 | 8 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ3-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-3-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ6-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | ? | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ3,7-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methylenecyclohex-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1,7-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ2-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ1-Cannabidiol | 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ2-Cannabidiol | 1 and 4 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ6-Cannabidiol | 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-6-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ3-Cannabidiol | 1 | 2 | No | Unscheduled |

|

History

Efforts to isolate the active ingredients in cannabis were made in the 19th century.[citation needed] CBD was studied in 1940 from Minnesota wild hemp[48] and Egyptian Cannabis indica resin.[49] The chemical formula of CBD was proposed from a method for isolating it from wild hemp.[48] Its structure and stereochemistry were determined in 1963.[50]

Society and culture

Names

Cannabidiol is the generic name of the drug and its INN.[51]

Food and beverage

Food and beverage products containing CBD were introduced in the United States in 2017.[dubious – discuss][52] Hemp seed ingredients which do not naturally contain THC or CBD (but which may be contaminated with trace amounts on the outside during harvesting) were declared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as Generally recognized as safe (GRAS) in December 2018. CBD itself has not been declared GRAS, and under U.S. federal law is illegal to sell as a food, dietary supplement, or animal feed.[16] State laws vary considerably as non-medical cannabis and derived products have been legalized in some jurisdictions in the 2010s.

Similar to energy drinks and protein bars which may contain vitamin or herbal additives, food and beverage items can be infused with CBD as an alternative means of ingesting the substance.[53] In the United States, numerous products are marketed as containing CBD, but in reality contain little or none.[16][54] Some companies marketing CBD-infused food products with claims that are similar to the effects of prescription drugs have received warning letters from the Food and Drug Administration for making unsubstantiated health claims.[16][55] In February 2019, the New York City Department of Health announced plans to fine restaurants that sell food or drinks containing CBD, beginning in October 2019.[56]

Plant sources

Selective breeding of cannabis plants has expanded and diversified as commercial and therapeutic markets develop.[16] Some growers in the US succeeded in lowering the proportion of CBD-to-THC to accommodate customers who preferred varietals that were more mind-altering due to the higher THC and lower CBD content.[57] In the US, hemp is classified by the federal government as cannabis containing no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. This classification was established in the 2018 Farm Bill and was refined to include hemp-sourced extracts, cannabinoids, and derivatives in the definition of hemp.[58]

Non-psychoactivity

CBD does not appear to have any psychotropic ("high") effects such as those caused by ∆9-THC in marijuana, but is under preliminary research for its possible anti-anxiety and anti-psychotic effects.[8][9][11] As the legal landscape and understanding about the differences in medical cannabinoids unfolds, experts are working to distinguish "medical marijuana" (with varying degrees of psychotropic effects and deficits in executive function) – from "medical CBD therapies" which would commonly present as having a reduced or non-psychoactive side-effect profile.[9][11][59]

Various strains of "medical marijuana" are found to have a significant variation in the ratios of CBD-to-THC, and are known to contain other non-psychotropic cannabinoids.[60] Any psychoactive marijuana, regardless of its CBD content, is derived from the flower (or bud) of the genus Cannabis. As defined by U.S. federal law, non-psychoactive hemp (also commonly-termed industrial hemp), regardless of its CBD content, is any part of the cannabis plant, whether growing or not, containing a ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of no more than 0.3% on a dry-weight basis.[61] Certain standards are required for legal growing, cultivating, and producing the hemp plant. The Colorado Industrial Hemp Program registers growers of industrial hemp and samples crops to verify that the dry-weight THC concentration does not exceed 0.3%.[61]

CBD and sport

CBD has been used by professional and amateur athletes across disciplines and countries, with the World Anti-Doping Agency removing CBD from its banned substances list. The United States Anti-Doping Agency and United Kingdom-Anti-Doping Agency do not have anti-CBD policies, with the latter stating that, "CBD is not currently listed on the World Anti-Doping Agency Prohibited List. As a result, it is permitted to use in sport. All other cannabinoids (including but not limited to cannabis, hashish, marijuana, and THC) are prohibited in-competition. The intention of the regulations is to prohibit cannabinoids that activate the same receptors in the brain as activated by THC."[62][63] In 2019, the leading cannabis products manufacturer, Canopy Growth, acquired majority ownership of BioSteel Sports Nutrition, which is developing CBD products under endorsement by numerous professional athletes.[64] The National Hockey League Alumni Association began a project with Canopy Growth to determine if CBD or other cannabis products might improve neurological symptoms and quality of life in head-injured players.[64] Numerous professional athletes use CBD, primarily for treating pain.[64][65][66]

Legal status

United Nations

Cannabidiol is not scheduled under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances or any other UN drug treaties.[67] In 2018, the World Health Organization recommended that CBD remain unscheduled.[68]

Australia

Prescription medicine (Schedule 4) for therapeutic use containing 2 percent (2.0%) or less of other cannabinoids commonly found in cannabis (such as ∆9-THC). A schedule 4 drug under the SUSMP is a Prescription Only Medicine, or Prescription Animal Remedy – Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription.[69]

Following a change in legislation in 2017, CBD was changed from a schedule 9 drug to a schedule 4 drug, meaning that it is legally available in Australia.[70]

Bulgaria

In 2020, Bulgaria became the first EU country to allow retail sales of food products and supplements containing CBD, despite the ongoing discussion within the EU about the classification of CBD as a Novel food.[71]

Canada

In October 2018, cannabidiol became legal for recreational and medical use by the federal Cannabis Act.[72][73][74] As of August 2019, CBD products in Canada could only be sold by authorized retailers or federally licensed medical companies, limiting their access to the general public.[75] The Canadian government states that CBD products "are subject to all of the rules and requirements that apply to cannabis under the Cannabis Act and its regulations."[72] It requires "a processing licence to manufacture products containing CBD for sale, no matter what the source of the CBD is, and that CBD and products containing CBD, such as cannabis oil, may only be sold" by an authorized retailer or licensed seller of medical CBD.[72] Edible CBD products were scheduled to be permitted for sale in Canada on October 17, 2019, and are to be used only for human consumption.[72]

European Union

In 2019, the European Commission announced that CBD and other cannabinoids would be classified as "novel foods",[76] meaning that CBD products would require authorization under the EU Novel Food Regulation stating: because "this product was not used as a food or food ingredient before May 15, 1997, before it may be placed on the market in the EU as a food or food ingredient, a safety assessment under the Novel Food Regulation is required."[77] The recommendation – applying to CBD extracts, synthesized CBD, and all CBD products, including CBD oil – was scheduled for a final ruling by the European Commission in March 2019.[76] If approved, manufacturers of CBD products would be required to conduct safety tests and prove safe consumption, indicating that CBD products would not be eligible for legal commerce until at least 2021.[76]

Cannabidiol is listed in the EU Cosmetics Ingredient Database (CosIng).[78] However, the listing of an ingredient, assigned with an INCI name, in CosIng does not mean it is to be used in cosmetic products or is approved for such use.[78]

Several industrial hemp varieties can be legally cultivated in Western Europe. A variety such as "Fedora 17" has a cannabinoid profile consistently around 1%, with THC less than 0.3%.[79]

Sweden

CBD is classified as a medical product in Sweden.[80]

New Zealand

In 2017 the government made changes to the regulations so that restrictions would be removed, which meant a doctor was able to prescribe cannabidiol to patients.[81]

The passing of the Misuse of Drugs (Medicinal Cannabis) Amendment Act in December 2018 means cannabidiol is no longer a controlled drug in New Zealand, but is a prescription medicine under the Medicines Act, with the restriction that "the amount of tetrahydrocannabinols and psychoactive related substances must not exceed 2 percent of the total CBD tetrahydrocannabinol and psychoactive related substances content".[82]

United Kingdom

Cannabidiol, in an oral-mucosal spray formulation combined with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, is a product available (by prescription only until 2017) for the relief of severe spasticity due to multiple sclerosis (where other anti-spasmodics have not been effective).[83]

Until 2017, products containing cannabidiol marketed for medical purposes were classed as medicines by the UK regulatory body, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and could not be marketed without regulatory approval for the medical claims.[84] As of 2018[update], cannabis oil is legal to possess, buy, and sell in the UK, providing the product does not contain more than 0.3% THC and is not advertised as providing a medicinal benefit.[85]

In January 2019, the UK Food Standards Agency indicated it would regard CBD products, including CBD oil, as a novel food having no history of use before May 1997, and stated that such products must have authorisation and proven safety before being marketed.[76][86] The deadline for companies to register a CBD product as an authorised novel food with the FSA is 31 March 2021; failure to register will exclude companies from selling CBD.[87]

United States

As of March 2020[update], CBD extracted from marijuana remains a Schedule I Controlled Substance,[15][16][88] and is not approved as a prescription drug, dietary supplement, or allowed for interstate commerce in the United States.[89] CBD derived from hemp (with 0.3% THC or lower) is legal to sell as a cosmetics ingredient, but cannot be sold under federal law as an ingredient in food, dietary supplements, or animal food.[15][16][90] It is a common misconception that the legal ability to sell hemp (which may contain CBD) makes CBD legal.[90][91]

In September 2018, following its approval by the FDA for rare types of childhood epilepsy,[14] Epidiolex was rescheduled (by the Drug Enforcement Administration) as a Schedule V drug to allow for its prescription use.[92] This allows GW Pharmaceuticals to sell Epidiolex, but it does not apply broadly and all other CBD-containing products remain Schedule I drugs.[15][92] Epidiolex still requires rescheduling in some states before it can be prescribed in those states.[93][94]

In 2013, a CNN program that featured Charlotte's Web cannabis brought increased attention to the use of CBD in the treatment of seizure disorders.[95][96] Since then, 16 states have passed laws to allow the use of CBD products with a physician's recommendation (instead of a prescription) for treatment of certain medical conditions.[97] This is in addition to the 30 states that have passed comprehensive medical cannabis laws, which allow for the use of cannabis products with no restrictions on THC content.[97] Of these 30 states, eight have legalized the use and sale of cannabis products without requirement for a physician's recommendation.[97] As of March 2020, CBD was not a FDA-approved drug eligible for interstate commerce,[16] and the FDA encouraged manufacturers to follow procedures for drug approval.[98]

Some manufacturers ship CBD products nationally, an illegal action which the FDA did not enforce in 2018, with CBD remaining the subject of an FDA investigational new drug evaluation, and is not considered legal as a dietary supplement or food ingredient, as of March 2020[update].[16][99] Federal illegality has made it difficult historically to conduct research on CBD.[100] CBD is openly sold in head shops and health food stores in some states where such sales have not been explicitly legalized.[101]

State and local governments may also regulate CBD. For example, the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources issued a rule in June 2019 aligning state CBD regulations with FDA regulations. This means that although recreational marijuana is legal in the state, CBD cannot legally be sold in food or as a dietary supplement under state law.[102]

Health concerns

In November 2019, the FDA issued concerns about the safety of CBD, stating that CBD use has potential to cause liver injury, interfere with the mechanisms of prescription drugs, produce gastrointestinal disorders, or affect alertness and mood.[89] In March 2020, the FDA updated its safety concerns about CBD, acknowledging the unknown effects of protracted use, how it affects the developing brain, fetus or infants during breastfeeding, whether it interacts with dietary supplements or prescription drugs, whether male fertility is affected, and its possible side effects, such as drowsiness.[103]

In February 2020, the UK FSA advised vulnerable people, such as pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and those already taking medication for other medical concerns not to take CBD. The FSA further recommended that healthy adults should not consume more than 70 mg CBD per day.[87]

2018 Farm Bill and hemp

The 2014 Farm Bill[104] legalized the sale of "non-viable hemp material" grown within states participating in the Hemp Pilot Program which defined hemp as cannabis containing less than 0.3% of THC.[105] Although the 2018 United States Farm Bill led some states to interpret the bill as enabling private farmers to grow hemp for extraction and retail of CBD, federal agencies – including the FDA and DEA[106] – retained regulatory authority over hemp-derived CBD as a Schedule I substance.[15][91] By federal law, private enterprises developing hemp-derived CBD are obligated to cultivate hemp exclusively for industrial purposes, which involve the fiber and seed, but not the flowering tops which contain THC and CBD.[15] Hemp CBD products may not be sold into general commerce, but rather are allowed only for research.[15][103] The 2018 Farm Bill requires that research and development of CBD for a therapeutic purpose would have to be conducted under notification and reporting to the FDA.[15][91][103]

FDA warning letters

From 2015 to November 2019, the FDA issued dozens of warning letters to American manufacturers of CBD products for false advertising and illegal interstate marketing of CBD as an unapproved drug to treat diseases, such as cancer, osteoarthritis, symptoms of opioid withdrawal, Alzheimer's disease, and pet disorders.[107][108] The FDA said that the letters were issued to enforce action against companies that were deceiving consumers by marketing illegal products for which there was insufficient evidence of safety and efficacy to treat diseases.[107] In July 2019, the FDA stated: "Selling unapproved products with unsubstantiated therapeutic claims — such as claims that CBD products can treat serious diseases and conditions — can put patients and consumers at risk by leading them to put off important medical care. Additionally, there are many unanswered questions about the science, safety, effectiveness and quality of unapproved products containing CBD."[107]

In October 2019, the FDA and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced a joint warning to a Florida supplements company marketing CBD products as unapproved drugs to treat childhood autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, acne, and infant teething and ear aches.[109][110] The warning also applied to hemp CBD capsules and oil that were being marketed illegally while not adhering to the federal definition of a dietary supplement.[110] Additionally, Idaho, Nebraska, and South Dakota are the only three states as of January 7th, 2020 to ban the use of CBD in any form or capacity.[111]

Mislabeling and poisoning

A 2017 analysis of CBD content in oil, tincture or liquid vape products purchased online in the United States showed that 69% were mislabeled, with 43% having higher and 26% having lower content than stated on product labels.[112][113]

As of September 2019[update], 1,085 people contacted US poison control centers about CBD-induced illnesses, doubling the number of cases over the 2018 rate and increasing by 9 times the case numbers of 2017.[114] Of cases reported in 2019, more than 33% received medical attention and 46 people were admitted to a hospital intensive care unit.[113]

Switzerland

While THC remains illegal, CBD is not subject to the Swiss Narcotic Acts because this substance does not produce a comparable psychoactive effect. Cannabis products containing less than 1% THC can be sold and purchased legally.[115]

Research

As of 2019[update], there was only limited high-quality evidence for cannabidiol having a neurological effect in people,[8][9][22][116] mainly due to the weak design and small number of subjects in randomized controlled trials.[116]

See also

References

- ^ "cannabidiol (CHEBI:69478)". www.ebi.ac.uk.

- ^ "Sativex (Cannabidiol/Tetrahydrocannabinol) Bayer Label" (PDF). bayer.ca. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Epidiolex (Cannabidiol) FDA Label" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved June 28, 2018. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 210365

- ^ a b Mechoulam R, Parker LA, Gallily R (November 2002). "Cannabidiol: an overview of some pharmacological aspects". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11 Suppl): 11S–19S. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb05998.x. PMID 12412831.

- ^ a b Scuderi C, Filippis DD, Iuvone T, Blasio A, Steardo A, Esposito G (May 2009). "Cannabidiol in medicine: a review of its therapeutic potential in CNS disorders". Phytotherapy Research (Review). 23 (5): 597–602. doi:10.1002/ptr.2625. PMID 18844286.

- ^ a b c Devinsky, Orrin; Cilio, Maria Roberta; Cross, Helen; Fernandez-Ruiz, Javier; French, Jacqueline; Hill, Charlotte; Katz, Russell; Di Marzo, Vincenzo; Jutras-Aswad, Didier; Notcutt, William George; Martinez-Orgado, Jose; Robson, Philip J.; Rohrback, Brian G.; Thiele, Elizabeth; Whalley, Benjamin; Friedman, Daniel (May 22, 2014). "Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders". Epilepsia. 55 (6): 791–802. doi:10.1111/epi.12631. PMC 4707667. PMID 24854329.

- ^ a b c Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS (December 2012). "Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (Review). 367 (1607): 3364–78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0389. PMC 3481531. PMID 23108553.

- ^ a b c d Black, Nicola; Stockings, Emily; Campbell, Gabrielle; Tran, Lucy T.; Zagic, Dino; Hall, Wayne D.; Farrell, Michael; Degenhardt, Louisa (December 2019). "Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 6 (12): 995–1010. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30401-8. ISSN 2215-0374. PMC 6949116. PMID 31672337.

- ^ a b c d e f VanDolah, Harrison J.; Bauer, Brent A.; Mauck, Karen F. (September 2019). "Clinicians' Guide to Cannabidiol and Hemp Oils". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 94 (9): 1840–1851. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.003. ISSN 1942-5546. PMID 31447137.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 42 (help) - ^ a b c d Pisanti S, Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Lamberti A, Ranieri R, Cuomo G, Abate M, Faggiana G, Proto MC, Fiore D, Laezza C, Bifulco M (July 2017). "Cannabidiol: State of the art and new challenges for therapeutic applications". Pharmacol. Ther. 175: 133–150. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.041. PMID 28232276.

- ^ a b c Iseger TA, Bossong MG (March 2015). "A systematic review of the antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol in humans". Schizophrenia Research. 162 (1–3): 153–61. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.033. PMID 25667194.

- ^ a b Boggs, Douglas L; Nguyen, Jacques D; Morgenson, Daralyn; Taffe, Michael A; Ranganathan, Mohini (2018). "Clinical and preclinical evidence for functional interactions of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol". Neuropsychopharmacology. 43 (1): 142–154. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.209. ISSN 0893-133X. PMC 5719112. PMID 28875990.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Soydaner U, Öztürk E, Schibano D, Simsir Y, Navarro P, Etxebarria N, Usobiaga A (February 2016). "Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes". Journal of Natural Products. 79 (2): 324–31. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00949. PMID 26836472.

- ^ a b c "FDA approves first drug comprised of an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mead, Alice (2017). "The legal status of cannabis (marijuana) and cannabidiol (CBD) under U.S. law". Epilepsy and Behavior (Review). 70 (Pt B): 288–291. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.021. ISSN 1525-5050. PMID 28169144.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD)". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 11, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "FDA approves first drug comprised of an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy". US Food and Drug Administration. June 25, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Stockings E, Zagic D, Campbell G, Weier M, Hall WD, Nielsen S, Herkes GK, Farrell M, Degenhardt L (July 2018). "Evidence for cannabis and cannabinoids for epilepsy: a systematic review of controlled and observational evidence". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 89 (7): 741–753. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-317168. PMID 29511052.

- ^ a b Elliott, Jesse; DeJean, Deirdre; Clifford, Tammy; Coyle, Doug; Potter, Beth K; Skidmore, Becky; Alexander, Christine; Repetski, Alexander E.; Shukla, Vijay; McCoy, Bláthnaid; Wells, George A. (2020). "Cannabis-based products for pediatric epilepsy: An updated systematic review". Seizure. 75: 18–22. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2019.12.006. ISSN 1059-1311. PMID 31865133.

- ^ Silva TB, Balbino CQ, Weiber AF (May 1, 2015). "The relationship between cannabidiol and psychosis: A review". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 27 (2): 134–41. PMID 25954940.

- ^ a b Blessing EM, Steenkamp MM, Manzanares J, Marmar CR (October 2015). "Cannabidiol as a Potential Treatment for Anxiety Disorders". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 825–36. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0387-1. PMC 4604171. PMID 26341731.

- ^ a b Prud'homme M, Cata R, Jutras-Aswad D (2015). "Cannabidiol as an intervention for addictive behaviors: A systematic review of the evidence". Substance Abuse. 9: 33–8. doi:10.4137/SART.S25081. PMC 4444130. PMID 26056464.

- ^ "What You Should Know About Using Cannabis, Including CBD, When Pregnant or Breastfeeding". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P, van den Brink W, Le Foll B, Hall W, Rehm J, Room R (August 2017). "Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines: A Comprehensive Update of Evidence and Recommendations". American Journal of Public Health. 107 (8): e1–e12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818. PMC 5508136. PMID 28644037.

- ^ Iffland K, Grotenhermen F (2017). "An Update on Safety and Side Effects of Cannabidiol: A Review of Clinical Data and Relevant Animal Studies". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2 (1): 139–154. doi:10.1089/can.2016.0034. PMC 5569602. PMID 28861514.

- ^ Bornheim LM, Kim KY, Li J, Perotti BY, Benet LZ (August 1995). "Effect of cannabidiol pretreatment on the kinetics of tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in mouse brain". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 23 (8): 825–831. PMID 7493549.

- ^ Klein C, Karanges E, Spiro A, Wong A, Spencer J, Huynh T, Gunasekaran N, Karl T, Long LE, Huang XF, Liu K, Arnold JC, McGregor IS (November 2011). "Cannabidiol potentiates Δ⁹-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) behavioural effects and alters THC pharmacokinetics during acute and chronic treatment in adolescent rats". Psychopharmacology. 218 (2): 443–457. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2342-0. PMID 21667074.

- ^ Ghovanloo MR, Shuart NG, Mezeyova M, Dean RA, Ruben PC, Goodchild SJ (September 2018). "Inhibitory effects of cannabidiol on voltage-dependent sodium currents". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 293 (43): 16546–16558. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.004929. PMC 6204917. PMID 30219789.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nadulski T, Pragst F, Weinberg G, Roser P, Schnelle M, Fronk EM, Stadelmann AM (December 2005). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study about the effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on the pharmacokinetics of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) after oral application of THC verses standardized cannabis extract". Ther Drug Monit. 27 (6): 799–810. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000177223.19294.5c. PMID 16306858.

- ^ Lucas, Catherine J.; Galettis, Peter; Schneider, Jennifer (November 2018). "The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids: The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 84 (11): 2477–2482. doi:10.1111/bcp.13710. PMC 6177698. PMID 30001569.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (August 2007). "Cannabidiol--recent advances". Chemistry & Biodiversity (Review). 4 (8): 1678–92. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

- ^ a b Pertwee RG (January 2008). "The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. PMC 2219532. PMID 17828291.

- ^ Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, Leonova J, Elebring T, Nilsson K, Drmota T, Greasley PJ (December 2007). "The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (7): 1092–101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460. PMC 2095107. PMID 17876302.

- ^ Laun AS, Shrader SH, Brown KJ, Song ZH (2019). "GPR3, GPR6, and GPR12 as novel molecular targets: their biological functions and interaction with cannabidiol". Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 40 (3): 300–308. doi:10.1038/s41401-018-0031-9. PMC 6460361. PMID 29941868.

- ^ Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK (August 2005). "Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors". Neurochemical Research. 30 (8): 1037–43. doi:10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. PMID 16258853.

- ^ Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Tränkle C, Schlicker E (February 2006). "Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 372 (5): 354–61. doi:10.1007/s00210-006-0033-x. PMID 16489449.

- ^ Russo, E. B. (2008). "Cannabinoids in the management of difficult to treat pain". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (1): 245–259. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S1928. PMC 2503660. PMID 18728714.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Sativex Oromucosal Spray". Medsafe, New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. December 19, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Jones PG, Falvello L, Kennard O, Sheldrick GM, Mechoulam R (1977). "Cannabidiol". Acta Crystallogr. B. 33 (10): 3211–3214. doi:10.1107/S0567740877010577.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Ben-Zvi Z, Gaoni Y (August 1968). "Hashish--13. On the nature of the Beam test". Tetrahedron. 24 (16): 5615–24. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88159-1. PMID 5732891.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1966). "Hashish—VII The isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinols". Tetrahedron. 22 (4): 1481–1488. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99446-3.

- ^ Küppers, F.J.E.M.; Bercht, C.A.L.; Salemink, C.A.; Lousberg, R.J.J.Ch.; Terlouw, J.K.; Heerma, W. (1975), "Cannabis—XV: Pyrolysis of cannabidiol. Structure elucidation of four pyrolytic products", Tetrahedron, 31 (13–14): 1513–1516, doi:10.1016/0040-4020(75)87002-5

- ^ Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C, Ohloff G, Eschenmoser A (March 1967). "[Synthesis and optical rotation of the (-)-cannabidiols]". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 50 (2): 719–23. doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500235. PMID 5587099.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1985). "Boron trifluoride etherate on alumuna — a modified Lewis acid reagent. An improved synthesis of cannabidiol". Tetrahedron Letters. 26 (8): 1083–1086. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98518-6.

- ^ Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi A, Wang YG (June 2006). "Synthesis of cannabidiols via alkenylation of cyclohexenyl monoacetate". Organic Letters. 8 (13): 2699–702. doi:10.1021/ol060692h. PMID 16774235.

- ^ Taura F, Sirikantaramas S, Shoyama Y, Yoshikai K, Shoyama Y, Morimoto S (June 2007). "Cannabidiolic-acid synthase, the chemotype-determining enzyme in the fiber-type Cannabis sativa". FEBS Letters. 581 (16): 2929–34. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.043. PMID 17544411.

- ^ Marks MD, Tian L, Wenger JP, Omburo SN, Soto-Fuentes W, He J, Gang DR, Weiblen GD, Dixon RA (2009). "Identification of candidate genes affecting Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol biosynthesis in Cannabis sativa". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (13): 3715–26. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp210. PMC 2736886. PMID 19581347.

- ^ a b Adams, Roger; Hunt, Madison; Clark, J. H. (1940). "Structure of cannabidiol, a product isolated from the marihuana extract of Minnesota wild hemp. I". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 62 (1): 196–200. doi:10.1021/ja01858a058. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Jacob, A.; Todd, A. R. (1940). "Cannabidiol and cannabol, constituents of Cannabis indica resin". Nature. 145 (3670): 350. Bibcode:1940Natur.145..350J. doi:10.1038/145350a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Mechoulam, R.; Shvo, Y. (1963). "Hashish". Tetrahedron. 19 (12): 2073–2078. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(63)85022-x. ISSN 0040-4020. PMID 5879214.

- ^ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 30 (2): 241. 2016.

- ^ "Billboard featuring hemp leaf raises questions about new beverage for sale in Cincinnati | WLWT5". WLWT5. September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ "CBD-Infused Foods Becoming a New Health Trend and Penetrating the Market". Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ "Warning Letters and Test Results for Cannabidiol-Related Products". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). November 2, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Fox, Arent; Ravitz, James R.; Leongini, Emily M.; Brian J., Malkin. "Companies Marketing CBD Products Be Warned: FDA Is Watching". Lexology. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "New York City plans to fine restaurants using CBD in food and drinks". CNBC. February 15, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Romney, Lee (September 13, 2012). "On the frontier of medical pot to treat boy's epilepsy". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "7 U.S. Code § 5940 – Legitimacy of industrial hemp research". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Sachs J, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D (October 2015). "Safety and Toxicology of Cannabinoids". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 735–46. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0380-8. PMC 4604177. PMID 26269228.

- ^ Izzo AA, Borrelli F, Capasso R, Di Marzo V, Mechoulam R (October 2009). "Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: new therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 30 (10): 515–27. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.006. PMID 19729208.

- ^ a b "Industrial hemp". Department of Agriculture, State of Colorado. 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ "Athlete Advisory Note: Cannabidiol (CBD)". United Kingdom Anti-Doping Agency. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ "Athletes: 6 things to know about cannabidiol". US Anti-Doping Agency. October 23, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Donna Spencer (October 2, 2019). "Canopy cannabis company buys ex-NHL player's sports nutrition business". CTV Business. The Canadian Press. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

BioSteel's brand ambassadors also include well-known athletes across major sports leagues in North America, which could be beneficial as the company's attempt to push regulated CBD nutrition products into the mainstream health and wellness segments

- ^ Amanda Loudin (December 7, 2019). "As more pro athletes use cannabis for aches and pain, the more they run afoul of rules". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Sara Harrison (September 28, 2019). "Lots of athletes say CBD Is a better painkiller. Is It?". Wired. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "International Drug Scheduling; Convention on Psychotropic Substances; Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs; World Health Organization; Scheduling Recommendations; Dronabinol (delta". Federal Register. March 1, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Angell, Tom (August 13, 2018). "UN Launches First-Ever Full Review Of Marijuana's Status Under International Law". Marijuana Moment. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Poisons Standard June 2017". Legislation.gov.au. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ Administration, Australian Government Department of Health Therapeutic Goods (May 31, 2017). "1.1 Cannabis - Scheduling delegate's final decisions: Cannabis, May 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Hasse, Javier. "This EU country has become the first to allow free sale Of CBD". Forbes. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Cannabidiol (CBD)". Government of Canada. August 13, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "Health products containing cannabis or for use with cannabis: Guidance for the Cannabis Act, the Food and Drugs Act, and related regulations". Government of Canada. July 11, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ Communications, Government of Canada, Department of Justice, Electronic (June 20, 2018). "Cannabis Legalization and Regulation". www.justice.gc.ca.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "'It should be available': Natural health food stores hope to cash in on CBD craze". CBC News. August 6, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Will Chu (January 31, 2019). "Updated EC ruling for CBD classes supplement ingredient as Novel Food". NutraIngredients.com, William Reed Business Media Ltd. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Cannabinoids, searched in the EU Novel food catalogue (v.1.1)". European Commission. January 1, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "CosIng – Cosmetics – Cannabidiol". European Commission. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ Fournier G, Beherec O, Bertucelli S (2003). "Intérêt du rapport Δ-9-THC / CBD dans le contrôle des cultures de chanvre industriel" [The advantage of the Δ-9-THC / CBD ratio in the control of industrial hemp crops]. Annales de Toxicologie Analytique (in French). 15 (4): 250–59. doi:10.1051/ata/2003003.

- ^ "CBD products should follow the drug laws". Swedish Medical Products Agency. April 4, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "Doctors now able to prescribe cannabidiol". radionz.co.nz. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ "CBD products". www.health.govt.nz. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Sativex Oromucosal Spray – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". Medicines.org.uk (eMC). Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "MHRA statement on products containing Cannabidiol (CBD)". Gov.uk. December 14, 2016.

- ^ "What are the rules about cannabis oil in the UK?". BBC News – Health. July 26, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Gunn L, Haigh L (January 29, 2019). "British watchdog deems CBD a novel food, seeks to curtail sale on UK market". Nutrition Insight, CNS Media BV. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "Food Standards Agency sets deadline for the CBD industry and provides safety advice to consumers". UK Food Standards Agency. February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Conaway, K. Michael (December 20, 2018). "Text - H.R.2 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018". www.congress.gov. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "What You Need to Know (And What We're Working to Find Out) About Products Containing Cannabis or Cannabis-derived Compounds, Including CBD". US Food and Drug Administration. November 26, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Jann Bellamy (May 9, 2019). "FDA: No CBD in dietary supplements or foods for now, but let's talk". Science-Based Medicine.

- ^ a b c Amy Abernethy; Lowell Schiller (July 17, 2019). "FDA is Committed to Sound, Science-based Policy on CBD". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "DEA reschedules Epidiolex, marijuana-derived drug, paving the way for it to hit the market". CNBC. September 27, 2018.

- ^ "Epilepsy Foundation Statement on DEA's Scheduling of Epidiolex" (Press release). Landover, MD: Epilepsy Foundation. September 27, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "State Rescheduling for FDA-approved Therapies Derived from CBD". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Maa E, Figi P (June 2014). "The case for medical marijuana in epilepsy". Epilepsia. 55 (6): 783–86. doi:10.1111/epi.12610. PMID 24854149.

- ^ Young, Saundra. "Marijuana stops child's severe seizures". CNN. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "State Medical Marijuana Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. April 27, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "FDA and Cannabis: Research and Drug Approval Process". US Food and Drug Administration. January 14, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "FDA and Marijuana: Questions and Answers. No. 12 – Can products that contain THC or cannabidiol (CBD) be sold as dietary supplements?". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 20, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ Corba, Jacqueline. "Super Bowl Champ: CBD Can Solve NFL's Opioid Problem'". Cheddar. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ Gaines, Lee V. (March 23, 2017). "Why are CBD products sold over the counter some places and tightly regulated in others?". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Massachusetts says hemp-derived CBD is illegal — but CBD stores are still everywhere

- ^ a b c Stephen M. Hahn (March 5, 2020). "FDA Advances Work Related to Cannabidiol Products with Focus on Protecting Public Health, Providing Market Clarity". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "The 2014 Farm Bill". thefarmbill.com. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Zhang, Mona. "No, CBD Is Not 'Legal in All 50 States'". Forbes. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "DEA announces steps necessary to improve access to marijuana research". United States Drug Enforcement Administration. August 26, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "FDA warns company marketing unapproved cannabidiol products with unsubstantiated claims to treat cancer, Alzheimer's disease, opioid withdrawal, pain and pet anxiety". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

Unlike drugs approved by the FDA, the manufacturing process of these products has not been subject to FDA review as part of the drug approval process, and there has been no FDA evaluation of whether these products are effective for their intended use, what the proper dosage is, how they could interact with FDA-approved drugs, or whether they have dangerous side effects or other safety concerns.

- ^ "Warning Letters and Test Results for Cannabidiol-Related Products". US Food and Drug Administration. November 26, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

...these products are not approved by FDA for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of any disease. Consumers should beware purchasing and using any such products.

- ^ "FTC and FDA Warn Florida Company Marketing CBD Products about Claims Related to Treating Autism, ADHD, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Other Medical Conditions". US Federal Trade Commission (FTC). October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Donald D. Ashley; Mary K. Engle (October 22, 2019). "Warning letter: Rooted Apothecary LLC". Office of Compliance, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration; US Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ https://www.cbdschool.com/cbd-laws-by-state-2020/

- ^ Bonn-Miller, Marcel O.; Loflin, Mallory J. E.; Thomas, Brian F.; Marcu, Jahan P.; Hyke, Travis; Vandrey, Ryan (November 7, 2017). "Labeling Accuracy of Cannabidiol Extracts Sold Online". JAMA. 318 (17): 1708–1709. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11909. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 5818782. PMID 29114823.

- ^ a b Dawn MacKeen (October 16, 2019). "Scam or Not: What Are the Benefits of CBD?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ "Cannabidiol (CBD)". American Association of Poison Control Centers. September 30, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ "Cannabis à faible teneur en THC et CBD" (in French). BAG.Admin.ch. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Hoch, Eva; Niemann, Dominik; von Keller, Rupert; Schneider, Miriam; Friemel, Chris M.; Preuss, Ulrich W.; Hasan, Alkomiet; Pogarell, Oliver (January 31, 2019). "How effective and safe is medical cannabis as a treatment of mental disorders? A systematic review". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 269 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1007/s00406-019-00984-4. ISSN 0940-1334. PMC 6595000. PMID 30706168.

Further reading

- Williams, Alex (October 27, 2018). "Why Is CBD Everywhere?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

- "Cannabidiol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.