Cannabidiol: Difference between revisions

Petrarchan47 (talk | contribs) →Epilepsy: + 2018 meta, comparison whole plant v purified |

move 2018 preliminary epilepsy study to Research; copyedit, fix ref details |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

An orally administered cannabidiol solution (brand name Epidiolex) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in June 2018 as a treatment for two rare forms of childhood epilepsy, [[Lennox-Gastaut syndrome]] and [[Dravet syndrome]].<ref name="fda18">{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm611046.htm|title=FDA approves first drug {{sic|comprised |hide=y|of}} an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy|publisher=US Food and Drug Administration|date=25 June 2018|accessdate=25 June 2018}}</ref> |

An orally administered cannabidiol solution (brand name Epidiolex) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in June 2018 as a treatment for two rare forms of childhood epilepsy, [[Lennox-Gastaut syndrome]] and [[Dravet syndrome]].<ref name="fda18">{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm611046.htm|title=FDA approves first drug {{sic|comprised |hide=y|of}} an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy|publisher=US Food and Drug Administration|date=25 June 2018|accessdate=25 June 2018}}</ref> |

||

A 2018 meta-analysis compared the therapeutic properties of "purified CBD" with full plant CBD-rich cannabis extracts with regard to treating refractory (treatment resistant) epilepsy, noting several differences. The daily average dose of patients using full plant extracts was more than four times lower than of those using purified CBD, which researchers suggested was due to the [[entourage effect]]. Adverse events, while both rare and mild, were more numerous with purified CBD, however this could be attributed to the higher dosage.<ref name="EpilepsyCBDvPurified">{{cite web |last1=Pamplona et al |title=Potential Clinical Benefits of CBD-Rich Cannabis Extracts Over Purified CBD in Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Observational Data Meta-analysis |url=https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2018.00759/full#h1 |website=Frontiers |publisher=Frontiers |accessdate=8 January 2019}}</ref> |

|||

===Other uses=== |

===Other uses=== |

||

| Line 209: | Line 207: | ||

==Research== |

==Research== |

||

A 2016 review indicated that cannabidiol was under [[basic research]] to identify its possible [[neurology|neurological]] effects,<ref name=jurkus/> although {{as of|2016|lc=y}}, there was limited high-quality evidence for such effects in people.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zlebnik NE, Cheer JF | title = Beyond the CB1 Receptor: Is Cannabidiol the Answer for Disorders of Motivation? | journal = Annual Review of Neuroscience | volume = 39 | pages = 1–17 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27023732 | pmc = 5818147 | doi = 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-014038 }}</ref><ref name=pmid26056464>{{cite journal | vauthors = Prud'homme M, Cata R, Jutras-Aswad D | title = Cannabidiol as an Intervention for Addictive Behaviors: A Systematic Review of the Evidence | journal = Substance Abuse | volume = 9 | pages = 33–8 | year = 2015 | pmid = 26056464 | pmc = 4444130 | doi = 10.4137/SART.S25081 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hurd YL, Yoon M, Manini AF, Hernandez S, Olmedo R, Ostman M, Jutras-Aswad D | title = Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage | journal = Neurotherapeutics | volume = 12 | issue = 4 | pages = 807–15 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26269227 | pmc = 4604178 | doi = 10.1007/s13311-015-0373-7 }}</ref> |

A 2016 review indicated that cannabidiol was under [[basic research]] to identify its possible [[neurology|neurological]] effects,<ref name=jurkus/> although {{as of|2016|lc=y}}, there was limited high-quality evidence for such effects in people.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zlebnik NE, Cheer JF | title = Beyond the CB1 Receptor: Is Cannabidiol the Answer for Disorders of Motivation? | journal = Annual Review of Neuroscience | volume = 39 | pages = 1–17 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27023732 | pmc = 5818147 | doi = 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-014038 }}</ref><ref name=pmid26056464>{{cite journal | vauthors = Prud'homme M, Cata R, Jutras-Aswad D | title = Cannabidiol as an Intervention for Addictive Behaviors: A Systematic Review of the Evidence | journal = Substance Abuse | volume = 9 | pages = 33–8 | year = 2015 | pmid = 26056464 | pmc = 4444130 | doi = 10.4137/SART.S25081 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hurd YL, Yoon M, Manini AF, Hernandez S, Olmedo R, Ostman M, Jutras-Aswad D | title = Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage | journal = Neurotherapeutics | volume = 12 | issue = 4 | pages = 807–15 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26269227 | pmc = 4604178 | doi = 10.1007/s13311-015-0373-7 }}</ref> A 2018 [[meta-analysis]] compared the potential [[therapy|therapeutic properties]] of "purified CBD" with full plant CBD-rich cannabis extracts with regard to treating refractory (treatment resistant) epilepsy, noting several differences.<ref name="Pamplona ">{{cite journal | last=Pamplona | first=Fabricio A. | last2=da Silva | first2=Lorenzo Rolim | last3=Coan | first3=Ana Carolina | title=Potential Clinical Benefits of CBD-Rich Cannabis Extracts Over Purified CBD in Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Observational Data Meta-analysis | journal=Frontiers in Neurology | volume=9 | date=12 September 2018 | issn=1664-2295 | pmid=30258398 | pmc=6143706 | doi=10.3389/fneur.2018.00759}}</ref> The daily average dose of people using full plant extracts was more than four times lower than of those using purified CBD, a possible [[entourage effect]] of CBD interacting with THC.<ref name=Pamplona/> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 17:22, 8 January 2019

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sativex (with THC), Epidiolex |

| Other names | CBD |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Inhalation (smoking, vaping), buccal (aerosol spray), oral (solution)[1][2] |

| Drug class | Cannabinoid |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | • Oral: 13–19%[3] • Inhaled: 31% (11–45%)[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 18–32 hours[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.215.986 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.464 g/mol g·mol−1 |

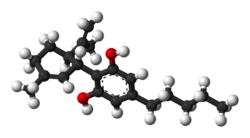

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 66 °C (151 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a phytocannabinoid discovered in 1940. It is one of some 113 identified cannabinoids in Cannabis plants, accounting for up to 40% of the plant's extract.[6] As of 2018, preliminary clinical research on cannabidiol included studies of anxiety, cognition, movement disorders, and pain.[7]

Cannabidiol can be taken into the body in multiple different ways, including by inhalation of cannabis smoke or vapor, as an aerosol spray into the cheek, and by mouth. It may be supplied as CBD oil containing only CBD as the active ingredient (no added THC or terpenes), a full-plant CBD-dominant hemp extract oil, capsules, dried cannabis, or as a prescription liquid solution.[2] CBD does not have the same psychoactivity as THC,[8][9][10] and may affect the actions of THC.[7][8][6][11] Although in vitro studies indicate CBD may interact with different biological targets, including cannabinoid receptors and other neurotransmitter receptors,[8][12] the mechanism of action for its possible biological effects has not been determined, as of 2018.[7][8]

In the United States, the cannabidiol drug Epidiolex has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of two epilepsy disorders.[13] Side effects of long-term use listed on the Epidiolex label include somnolence, decreased appetite, diarrhea, fatigue, malaise, weakness, sleeping problems, and others.[2]

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has assigned Epidiolex a Schedule V classification while non-Epidiolex CBD remains a Schedule I drug prohibited for any use.[14] CBD is not scheduled under any United Nations drug control treaties, and in 2018 the World Health Organization recommended that it remain unscheduled.[15]

Medical uses

Epilepsy

Medical reviews published in 2017 and 2018 incorporating numerous clinical trials concluded that cannabidiol is an effective treatment for certain types of childhood epilepsy.[16][17]

An orally administered cannabidiol solution (brand name Epidiolex) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in June 2018 as a treatment for two rare forms of childhood epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.[13]

Other uses

Preliminary research on other possible therapeutic uses for cannabidiol include several neurological disorders, but the findings have not been confirmed by sufficient high-quality clinical research to establish such uses in clinical practice.[8][18][19][20][21][5]

Side effects

Preliminary research indicates that cannabidiol may reduce adverse effects of THC, particularly those causing intoxication and sedation, but only at high doses.[22] Safety studies of cannabidiol showed it is well-tolerated, but may cause tiredness, diarrhea, or changes in appetite as common adverse effects.[23] Epidiolex documentation lists sleepiness, insomnia and poor quality sleep, decreased appetite, diarrhea, and fatigue.[2]

Potential interactions

Laboratory evidence indicated that cannabidiol may reduce THC clearance, increasing plasma concentrations which may raise THC availability to receptors and enhance its effect in a dose-dependent manner.[24][25] In vitro, cannabidiol inhibited receptors affecting the activity of voltage-dependent sodium and potassium channels, which may affect neural activity.[26] A small clinical trial reported that CBD partially inhibited the CYP2C-catalyzed hydroxylation of THC to 11-OH-THC.[27]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Cannabidiol has very low affinity for the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors but is said to act as an indirect antagonist of these receptors.[28][29] At the same time, it may potentiate the effects of THC by increasing CB1 receptor density or through another CB1 receptor-related mechanism.[30]

Cannabidiol has been found to act as an antagonist of GPR55, a G protein-coupled receptor and putative cannabinoid receptor that is expressed in the caudate nucleus and putamen in the brain.[31] It has also been found to act as an inverse agonist of GPR3, GPR6, and GPR12.[12] Although currently classified as orphan receptors, these receptors are most closely related phylogenetically to the cannabinoid receptors.[12] In addition to orphan receptors, CBD has been shown to act as a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist,[32] and this action may be involved in its antidepressant,[33][34] anxiolytic,[34][35] and neuroprotective effects.[36][37] It is an allosteric modulator of the μ- and δ-opioid receptors as well.[38] The pharmacological effects of CBD have additionally been attributed to PPARγ agonism and intracellular calcium release.[6]

Research suggests that CBD may exert some of its pharmacological action through its inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), which may in turn increase the levels of endocannabinoids, such as anandamide, produced by the body.[6] It has also been speculated that some of the metabolites of CBD have pharmacological effects that contribute to the biological activity of CBD.[39]

Cannabidiol is metabolized in the liver as well as the gut by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 enzymes, and UGT1A7, UGT1A9, and UGT2B7 isoforms.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of CBD is 13 to 19%, while its bioavailability via inhalation is 11 to 45% (mean 31%).[3][4] The elimination half-life of CBD is 18–32 hours.[5]

Pharmaceutical preparations

Nabiximols (brand name Sativex) is a patented medicine containing CBD and THC in equal proportions. The drug was approved by Health Canada in 2005 for prescription to treat central neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis, and in 2007 for cancer related pain.[40][41]

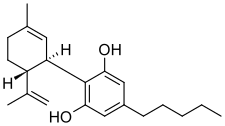

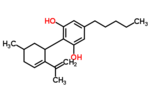

Chemistry

Cannabidiol is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents such as pentane. At room temperature, it is a colorless crystalline solid.[42] In strongly basic media and the presence of air, it is oxidized to a quinone.[43] Under acidic conditions it cyclizes to THC,[44] which also occurs during pyrolysis (smoking).[45] The synthesis of cannabidiol has been accomplished by several research groups.[46][47][48]

Biosynthesis

Cannabis produces CBD-carboxylic acid through the same metabolic pathway as THC, until the next to last step, where CBDA synthase performs catalysis instead of THCA synthase.[49]

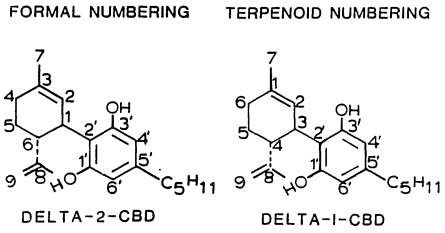

Isomerism

| Formal numbering | Terpenoid numbering | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | Structure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short name | Chiral centers | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers | ||||

| Δ5-Cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-5-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ4-Cannabidiol | 1 and 3 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ4-Cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-4-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ5-Cannabidiol | 1, 3 and 4 | 8 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ3-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-3-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ6-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | ? | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ3,7-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methylenecyclohex-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1,7-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ2-Cannabidiol | 1 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ1-Cannabidiol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ1-Cannabidiol | 3 and 6 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ2-Cannabidiol | 1 and 4 | 4 | No | Unscheduled |

|

| Δ6-Cannabidiol | 3 | 2-(6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-6-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-pentyl-1,3-benzenediol | Δ3-Cannabidiol | 1 | 2 | No | Unscheduled |

|

History

CBD was isolated from the cannabis plant in 1940, and its chemical structure was established in 1963.[7]

Society and culture

Names

Cannabidiol is the generic name of the drug and its INN.[51]

Food and beverage

Food and beverage products containing CBD were introduced in the United States in 2017.[52] Similar to energy drinks and protein bars which may contain vitamin or herbal additives, food and beverage items can be infused with CBD as an alternative means of ingesting the substance.[53] In the United States, numerous products are marketed as containing CBD, but in reality contain little or none.[54] Some companies marketing CBD-infused food products with claims that are similar to the effects of prescription drugs have received warning letters from the Food and Drug Administration for making unsubstantiated health claims.[55]

Plant sources

Selective breeding of cannabis plants has expanded and diversified as commercial and therapeutic markets develop. Some growers in the U.S. succeeded in lowering the proportion of CBD-to-THC to accommodate customers who preferred varietals that were more mind-altering due to the higher THC and lower CBD content.[56] Hemp is classified as any part of the cannabis plant containing no more than 0.3% THC in dry weight form (not liquid or extracted form).[57]

Legal status

Non-psychoactivity

CBD does not appear to have any psychotropic ("high") effects such as those caused by ∆9-THC in marijuana, but may have anti-anxiety and anti-psychotic effects.[9] As the legal landscape and understanding about the differences in medical cannabinoids unfolds, it will be increasingly important to distinguish "medical marijuana" (with varying degrees of psychotropic effects and deficits in executive function) – from "medical CBD therapies” which would commonly present as having a reduced or non-psychoactive side effect profile.[9][58]

Various strains of "medical marijuana" are found to have a significant variation in the ratios of CBD-to-THC, and are known to contain other non-psychotropic cannabinoids.[59] Any psychoactive marijuana, regardless of its CBD content, is derived from the flower (or bud) of the genus Cannabis. Non-psychoactive hemp (also commonly-termed industrial hemp), regardless of its CBD content, is any part of the cannabis plant, whether growing or not, containing a ∆-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of no more than three-tenths of one percent (0.3%) on a dry weight basis.[60] Certain standards are required for legal growing, cultivating and producing the hemp plant. The Colorado Industrial Hemp Program registers growers of industrial hemp and samples crops to verify that the THC concentration does not exceed 0.3% on a dry weight basis.[60]

United Nations

Cannabidiol is not scheduled under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances or any other UN drug treaty. In 2018, the World Health Organization recommended that CBD remain unscheduled.[15]

United States

In the United States, non-FDA approved CBD products are classified as Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act.[61] This means that production, distribution, and possession of non-FDA approved CBD products is illegal under federal law. In addition, in 2016 the Drug Enforcement Administration added "marijuana extracts" to the list of Schedule I drugs, which it defined as "an extract containing one or more cannabinoids that has been derived from any plant of the genus Cannabis, other than the separated resin (whether crude or purified) obtained from the plant."[62] Previously, CBD had simply been considered "marijuana", which is a Schedule I drug.[61][63]

In September 2018, following its approval by the FDA for rare types of childhood epilepsy,[13] Epidiolex was rescheduled (by the Drug Enforcement Administration) as a Schedule V drug to allow for its prescription use.[14] This change applies only to FDA-approved products containing no more than 0.1 percent THC.[14] This allows GW Pharmaceuticals to sell Epidiolex, but it does not apply broadly and all other CBD-containing products remain Schedule I drugs.[14] Epidiolex still requires rescheduling in some states before it can be prescribed in those states.[64][65]

A CNN program that featured Charlotte's Web cannabis in 2013 brought increased attention to the use of CBD in the treatment of seizure disorders.[66][67] Since then, 16 states have passed laws to allow the use of CBD products with a doctor's recommendation (instead of a prescription) for treatment of certain medical conditions.[68] This is in addition to the 30 states that have passed comprehensive medical cannabis laws, which allow for the use of cannabis products with no restrictions on THC content.[68] Of these 30 states, eight have legalized the use and sale of cannabis products without requirement for a doctor's recommendation.[68]

Some manufacturers ship CBD products nationally, an illegal action which the FDA has not enforced in 2018, with CBD remaining as the subject of an FDA investigational new drug evaluation and is not considered legal as a dietary supplement or food ingredient as of November 2018[update].[69] CBD is openly sold in head shops and health food stores in some states where such sales have not been explicitly legalized.[70][71]

The 2014 Farm Bill[72], legalized the sale of "non-viable hemp material" grown within states participating in the Hemp Pilot Program[73]. This legislation defined hemp as cannabis containing less than 0.3% of THC delta-9, grown within the regulatory framework of the Hemp Pilot Program. This has led many to insist that CBD manufactured from hemp, is legal in all 50 states and exempts its oversight by the DEA as a controlled substance[74]. The 2018 Farm Bill is anticipated to provide further clarity regarding hemp regulations[75].

Australia

Prescription medicine (Schedule 4) for therapeutic use containing 2 per cent (2.0%) or less of other cannabinoids commonly found in cannabis (such as ∆9-THC). A schedule 4 drug under the SUSMP is Prescription Only Medicine, or Prescription Animal Remedy – Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription.[76]

New Zealand

Cannabidiol is currently a class B1 controlled drug in New Zealand under the Misuse of Drugs Act. It is also a prescription medicine under the Medicines Act. In 2017 the rules were changed so that anyone wanting to use it could go to the Health Ministry for approval. Prior to this, the only way to obtain a prescription was to seek the personal approval of the Minister of Health.

Associate Health Minister Peter Dunne said restrictions would be removed, which means a doctor will now be able to prescribe cannabidiol to patients.[77]

Canada

On October 17, 2018, cannabidiol became legal for recreational and medical use.[78][79]

Europe

Cannabidiol is listed in the EU Cosmetics Ingredient Database (CosIng).[80] However, the listing of an ingredient, assigned with an INCI name, in CosIng does not mean it is to be used in cosmetic products nor approved for such use.[81]

Cannabidiol is listed in the EU Novel Food Catalogue.[82] This listing only applies to isolated or synthetic CBD, not to crude hemp extracts or tinctures naturally containing CBD.

The European Industrial Hemp Association has issued a position paper suggesting regulatory framework in EU.[83]

Several industrial hemp varieties can be legally cultivated in western Europe. A variety such as "Fedora 17" has a cannabinoid profile consistently around 1% cannabidiol (CBD) with THC less than 0.1%.[84]

Sweden

CBD is classified as a medical product in Sweden.[85]

United Kingdom

Cannabidiol, in an oral-mucosal spray formulation combined with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, was a prescription product available for relief of severe spasticity due to multiple sclerosis (where other anti-spasmodics have not been effective).[86]

Until 2017, products containing cannabidiol that are marketed for medical purposes were classed as medicines by the UK regulatory body, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and could not be marketed without regulatory approval for the medical claims.[87][88] CBD oil with THC content not exceeding 0.2% was legalized throughout the UK in 2017.[citation needed] Cannabis oil, however, remained illegal to possess, buy and sell.[89]

Switzerland

While THC remains illegal, CBD is not subject to the Swiss Narcotic Acts because this substance does not produce a comparable psychoactive effect.[90] Cannabis products containing less than 1% THC can be sold and purchased legally.[91]

Research

A 2016 review indicated that cannabidiol was under basic research to identify its possible neurological effects,[10] although as of 2016[update], there was limited high-quality evidence for such effects in people.[92][20][93] A 2018 meta-analysis compared the potential therapeutic properties of "purified CBD" with full plant CBD-rich cannabis extracts with regard to treating refractory (treatment resistant) epilepsy, noting several differences.[94] The daily average dose of people using full plant extracts was more than four times lower than of those using purified CBD, a possible entourage effect of CBD interacting with THC.[94]

See also

References

- ^ "Sativex (Cannabidiol/Tetrahydrocannabinol) Bayer Label" (PDF). bayer.ca. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Epidiolex (Cannabidiol) FDA Label" (PDF). fda.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2018. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 210365

- ^ a b Mechoulam R, Parker LA, Gallily R (November 2002). "Cannabidiol: an overview of some pharmacological aspects". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11 Suppl): 11S–19S. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb05998.x. PMID 12412831.

- ^ a b Scuderi C, Filippis DD, Iuvone T, Blasio A, Steardo A, Esposito G (May 2009). "Cannabidiol in medicine: a review of its therapeutic potential in CNS disorders". Phytotherapy Research (Review). 23 (5): 597–602. doi:10.1002/ptr.2625. PMID 18844286.

- ^ a b c Devinsky, Orrin; Cilio, Maria Roberta; Cross, Helen; Fernandez-Ruiz, Javier; French, Jacqueline; Hill, Charlotte; Katz, Russell; Di Marzo, Vincenzo; Jutras-Aswad, Didier; Notcutt, William George; Martinez-Orgado, Jose; Robson, Philip J.; Rohrback, Brian G.; Thiele, Elizabeth; Whalley, Benjamin; Friedman, Daniel (May 22, 2014). "Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders". Epilepsia. 55 (6): 791–802. doi:10.1111/epi.12631. PMC 4707667. PMID 24854329.

- ^ a b c d Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS (December 2012). "Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (Review). 367 (1607): 3364–78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0389. PMC 3481531. PMID 23108553.

- ^ a b c d Boggs, Douglas L; Nguyen, Jacques D; Morgenson, Daralyn; Taffe, Michael A; Ranganathan, Mohini (September 6, 2017). "Clinical and preclinical evidence for functional interactions of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol". Neuropsychopharmacology. 43 (1): 142–154. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.209. ISSN 0893-133X. PMC 5719112. PMID 28875990.

- ^ a b c d e Pisanti S, Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Lamberti A, Ranieri R, Cuomo G, Abate M, Faggiana G, Proto MC, Fiore D, Laezza C, Bifulco M (July 2017). "Cannabidiol: State of the art and new challenges for therapeutic applications". Pharmacol. Ther. 175: 133–150. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.041. PMID 28232276.

- ^ a b c Iseger TA, Bossong MG (March 2015). "A systematic review of the antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol in humans". Schizophrenia Research. 162 (1–3): 153–61. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.033. PMID 25667194.

- ^ a b Jurkus R, Day HL, Guimarães FS, Lee JL, Bertoglio LJ, Stevenson CW (2016). "Cannabidiol Regulation of Learned Fear: Implications for Treating Anxiety-Related Disorders". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 7: 454. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00454. PMC 5121237. PMID 27932983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Soydaner U, Öztürk E, Schibano D, Simsir Y, Navarro P, Etxebarria N, Usobiaga A (February 2016). "Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes". Journal of Natural Products. 79 (2): 324–31. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00949. PMID 26836472.

- ^ a b c Laun AS, Shrader SH, Brown KJ, Song ZH (June 2018). "GPR3, GPR6, and GPR12 as novel molecular targets: their biological functions and interaction with cannabidiol". Acta Pharmacol. Sin. doi:10.1038/s41401-018-0031-9. PMID 29941868.

- ^ a b c "FDA approves first drug comprised of an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy". US Food and Drug Administration. June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "DEA reschedules Epidiolex, marijuana-derived drug, paving the way for it to hit the market". CNBC. September 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Angell, Tom (August 13, 2018). "UN Launches First-Ever Full Review Of Marijuana's Status Under International Law". Marijuana Moment. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Stockings E, Zagic D, Campbell G, Weier M, Hall WD, Nielsen S, Herkes GK, Farrell M, Degenhardt L (July 2018). "Evidence for cannabis and cannabinoids for epilepsy: a systematic review of controlled and observational evidence". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 89 (7): 741–753. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-317168. PMID 29511052.

- ^ Perucca E (December 2017). "Cannabinoids in the Treatment of Epilepsy: Hard Evidence at Last?". J Epilepsy Res. 7 (2): 61–76. doi:10.14581/jer.17012. PMC 5767492. PMID 29344464.

- ^ Silva TB, Balbino CQ, Weiber AF (May 1, 2015). "The relationship between cannabidiol and psychosis: A review". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 27 (2): 134–41. PMID 25954940.

- ^ Blessing EM, Steenkamp MM, Manzanares J, Marmar CR (October 2015). "Cannabidiol as a Potential Treatment for Anxiety Disorders". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 825–36. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0387-1. PMC 4604171. PMID 26341731.

- ^ a b Prud'homme M, Cata R, Jutras-Aswad D (2015). "Cannabidiol as an Intervention for Addictive Behaviors: A Systematic Review of the Evidence". Substance Abuse. 9: 33–8. doi:10.4137/SART.S25081. PMC 4444130. PMID 26056464.

- ^ Fernández-Ruiz J, Sagredo O, Pazos MR, García C, Pertwee R, Mechoulam R, Martínez-Orgado J (February 2013). "Cannabidiol for neurodegenerative disorders: important new clinical applications for this phytocannabinoid?". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 75 (2): 323–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04341.x. PMC 3579248. PMID 22625422.

- ^ Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P, van den Brink W, Le Foll B, Hall W, Rehm J, Room R (August 2017). "Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines: A Comprehensive Update of Evidence and Recommendations". American Journal of Public Health. 107 (8): e1–e12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303818. PMID 28644037.

- ^ Iffland K, Grotenhermen F (2017). "An Update on Safety and Side Effects of Cannabidiol: A Review of Clinical Data and Relevant Animal Studies". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2 (1): 139–154. doi:10.1089/can.2016.0034. PMC 5569602. PMID 28861514.

- ^ Bornheim LM, Kim KY, Li J, Perotti BY, Benet LZ (August 1995). "Effect of cannabidiol pretreatment on the kinetics of tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites in mouse brain". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 23 (8): 825–831. PMID 7493549.

- ^ Klein C, Karanges E, Spiro A, Wong A, Spencer J, Huynh T, Gunasekaran N, Karl T, Long LE, Huang XF, Liu K, Arnold JC, McGregor IS (November 2011). "Cannabidiol potentiates Δ⁹-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) behavioural effects and alters THC pharmacokinetics during acute and chronic treatment in adolescent rats". Psychopharmacology. 218 (2): 443–457. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2342-0. PMID 21667074.

- ^ Ghovanloo MR, Shuart NG, Mezeyova M, Dean RA, Ruben PC, Goodchild SJ (September 2018). "Inhibitory effects of cannabidiol on voltage-dependent sodium currents". Journal of Biological Chemistry. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.004929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nadulski T, Pragst F, Weinberg G, Roser P, Schnelle M, Fronk EM, Stadelmann AM (December 2005). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study about the effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on the pharmacokinetics of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) after oral application of THC verses standardized cannabis extract". Ther Drug Monit. 27 (6): 799–810. PMID 16306858.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (August 2007). "Cannabidiol--recent advances". Chemistry & Biodiversity (Review). 4 (8): 1678–92. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

- ^ Pertwee RG (January 2008). "The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. PMC 2219532. PMID 17828291.

- ^ Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Hazekawa M, Sano K, Irie K, Orito K, Egawa T, Kitamura Y, Uchida N, Nishimura R, Egashira N, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M (January 2008). "Cannabidiol potentiates pharmacological effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol via CB(1) receptor-dependent mechanism". Brain Research. 1188: 157–64. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.090. PMID 18021759.

- ^ Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, Leonova J, Elebring T, Nilsson K, Drmota T, Greasley PJ (December 2007). "The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (7): 1092–101. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460. PMC 2095107. PMID 17876302.

- ^ Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK (August 2005). "Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors". Neurochemical Research. 30 (8): 1037–43. doi:10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. PMID 16258853.

- ^ Zanelati TV, Biojone C, Moreira FA, Guimarães FS, Joca SR (January 2010). "Antidepressant-like effects of cannabidiol in mice: possible involvement of 5-HT1A receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 122–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00521.x. PMC 2823358. PMID 20002102.

- ^ a b Resstel LB, Tavares RF, Lisboa SF, Joca SR, Corrêa FM, Guimarães FS (January 2009). "5-HT1A receptors are involved in the cannabidiol-induced attenuation of behavioural and cardiovascular responses to acute restraint stress in rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (1): 181–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00046.x. PMC 2697769. PMID 19133999.

- ^ Campos AC, Guimarães FS (August 2008). "Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats". Psychopharmacology. 199 (2): 223–30. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1168-x. PMID 18446323.

- ^ Mishima K, Hayakawa K, Abe K, Ikeda T, Egashira N, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M (May 2005). "Cannabidiol prevents cerebral infarction via a serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor-dependent mechanism". Stroke. 36 (5): 1077–82. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000163083.59201.34. PMID 15845890.

- ^ Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M, Ogata A, Hazekawa M, Liu AX, Fujioka M, Abe K, Hasebe N, Egashira N, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M (March 2007). "Repeated treatment with cannabidiol but not Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol has a neuroprotective effect without the development of tolerance". Neuropharmacology. 52 (4): 1079–87. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.11.005. PMID 17320118.

- ^ Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Tränkle C, Schlicker E (February 2006). "Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 372 (5): 354–61. doi:10.1007/s00210-006-0033-x. PMID 16489449.

- ^ Ujváry I, Hanuš L (2014). "Human Metabolites of Cannabidiol: A Review on Their Formation, Biological Activity, and Relevance in Therapy". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 1 (1): 90–101. doi:10.1089/can.2015.0012. PMC 5576600. PMID 28861484.

- ^ Russo, E. B. (2008). "Cannabinoids in the management of difficult to treat pain". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (1): 245–259. PMC 2503660. PMID 18728714.

- ^ Russo, E. B. (2008). "Cannabinoids in the management of difficult to treat pain". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (1): 245–259. PMC 2503660. PMID 18728714.

- ^ Jones PG, Falvello L, Kennard O, Sheldrick GM, Mechoulam R (1977). "Cannabidiol". Acta Crystallogr. B. 33 (10): 3211–3214. doi:10.1107/S0567740877010577.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Ben-Zvi Z, Gaoni Y (August 1968). "Hashish--13. On the nature of the Beam test". Tetrahedron. 24 (16): 5615–24. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(68)88159-1. PMID 5732891.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1966). "Hashish—VII The isomerization of cannabidiol to tetrahydrocannabinols". Tetrahedron. 22 (4): 1481–1488. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99446-3.

- ^ Cannabis—XV: Pyrolysis of cannabidiol. Structure elucidation of four pyrolytic products, doi:10.1016/0040-4020(75)87002-5

- ^ Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C, Ohloff G, Eschenmoser A (March 1967). "[Synthesis and optical rotation of the (-)-cannabidiols]". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 50 (2): 719–23. doi:10.1002/hlca.19670500235. PMID 5587099.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (1985). "Boron trifluoride etherate on alumuna — a modified Lewis acid reagent. An improved synthesis of cannabidiol". Tetrahedron Letters. 26 (8): 1083–1086. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98518-6.

- ^ Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi A, Wang YG (June 2006). "Synthesis of cannabidiols via alkenylation of cyclohexenyl monoacetate". Organic Letters. 8 (13): 2699–702. doi:10.1021/ol060692h. PMID 16774235.

- ^ Marks MD, Tian L, Wenger JP, Omburo SN, Soto-Fuentes W, He J, Gang DR, Weiblen GD, Dixon RA (2009). "Identification of candidate genes affecting Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol biosynthesis in Cannabis sativa". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (13): 3715–26. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp210. PMC 2736886. PMID 19581347.

- ^ Taura F, Sirikantaramas S, Shoyama Y, Yoshikai K, Shoyama Y, Morimoto S (June 2007). "Cannabidiolic-acid synthase, the chemotype-determining enzyme in the fiber-type Cannabis sativa". FEBS Letters. 581 (16): 2929–34. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.043. PMID 17544411.

- ^ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN)" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 30 (2): 241. 2016.

- ^ "Billboard featuring hemp leaf raises questions about new beverage for sale in Cincinnati | WLWT5". WLWT5. September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ "CBD-Infused Foods Becoming a New Health Trend and Penetrating the Market". Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ "Warning Letters and Test Results for Cannabidiol-Related Products". Food and Drug Administration. November 2, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Fox, Arent; Ravitz, James R.; Leongini, Emily M.; Brian J., Malkin. "Companies Marketing CBD Products Be Warned: FDA Is Watching". Lexology. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Romney, Lee (September 13, 2012). "On the frontier of medical pot to treat boy's epilepsy". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "How are CBD Extracts & Isolates Made?". IntelliCBD. June 22, 2018.

- ^ Sachs J, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D (October 2015). "Safety and Toxicology of Cannabinoids". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 735–46. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0380-8. PMC 4604177. PMID 26269228.

- ^ Izzo AA, Borrelli F, Capasso R, Di Marzo V, Mechoulam R (October 2009). "Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: new therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 30 (10): 515–27. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.006. PMID 19729208.

- ^ a b "Industrial hemp". Department of Agriculture, State of Colorado. 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Hudak, John; Stenglein, Christine (February 6, 2017). "DEA guidance is clear: Cannabidiol is illegal and always has been". FixGov. Brookings Institution. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Establishment of a New Drug Code for Marijuana Extract". Federal Register. 81 (240): 90194–90196. December 14, 2016. 81 FR 90195

- ^ "Clarification of the New Drug Code (7350) for Marijuana Extract". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ "Epilepsy Foundation Statement on DEA's Scheduling of Epidiolex" (Press release). Landover, MD: Epilepsy Foundation. September 27, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "State Rescheduling for FDA-approved Therapies Derived from CBD". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Maa E, Figi P (June 2014). "The case for medical marijuana in epilepsy". Epilepsia. 55 (6): 783–6. doi:10.1111/epi.12610. PMID 24854149.

- ^ Young, Saundra. "Marijuana stops child's severe seizures". CNN. CNN. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "State Medical Marijuana Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. April 27, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Stephen Daniells (November 6, 2018). "Top FDA official: 'Anyone who thinks CBD is lawful is mistaken'". NutraIngredients-USA, William Reed Business Media Ltd. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Summers DJ (March 22, 2017). "Is CBD Oil Legal? Depends on Where You Are and Who You Ask". Leafly. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Gaines, Lee V. (March 23, 2017). "Why are CBD products sold over the counter some places and tightly regulated in others?". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "the-2014-farm-bill | THE BILL". The 2014 Farm Bill. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "7 U.S. Code § 5940 - Legitimacy of industrial hemp research". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Zhang, Mona. "No, CBD Is Not 'Legal In All 50 States'". Forbes. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "2018 Farm Bill: What to watch for - from 6 hemp industry insiders". Hemp Industry Daily. September 4, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Poisons Standard June 2017". Legislation.gov.au. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "Doctors now able to prescribe cannabidiol". radionz.co.nz. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ "Health products containing cannabis or for use with cannabis: Guidance for the Cannabis Act, the Food and Drugs Act, and related regulations". Government of Canada. July 11, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ Communications, Government of Canada, Department of Justice, Electronic. "Cannabis Legalization and Regulation". www.justice.gc.ca.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "CosIng – Cosmetics – GROWTH – European Commission". Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "CosIng - Cosmetics - GROWTH - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "Food - European Commission".

- ^ "Support the EIHA CBD position paper - EIHA European Industrial Hemp Association".

- ^ Fournier G, Beherec O, Bertucelli S (2003). "Intérêt du rapport Δ-9-THC / CBD dans le contrôle des cultures de chanvre industriel" [The advantage of the Δ-9-THC / CBD ratio in the control of industrial hemp crops]. Annales de Toxicologie Analytique (in French). 15 (4): 250–259. doi:10.1051/ata/2003003.

- ^ "CBD products should follow the drug laws". Swedish Medical Products Agency. April 4, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "Sativex Oromucosal Spray – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) – (eMC)". Medicines.org.uk. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "MHRA statement on products containing Cannabidiol (CBD)". Gov.uk. December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Is CBD Legal in the UK? We explain the latest Cannabidiol (CBD) releases from the MHRA". The CBD Blog. October 31, 2018.

- ^ "CBD oil UK law: The latest news". Business Matters. July 23, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Products containing cannabidiol (CBD) – overview". swissmedic.ch. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Cannabis à faible teneur en THC et CBD". bag.admin.ch. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ Zlebnik NE, Cheer JF (July 2016). "Beyond the CB1 Receptor: Is Cannabidiol the Answer for Disorders of Motivation?". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 39: 1–17. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-014038. PMC 5818147. PMID 27023732.

- ^ Hurd YL, Yoon M, Manini AF, Hernandez S, Olmedo R, Ostman M, Jutras-Aswad D (October 2015). "Early Phase in the Development of Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Addiction: Opioid Relapse Takes Initial Center Stage". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (4): 807–15. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0373-7. PMC 4604178. PMID 26269227.

- ^ a b Pamplona, Fabricio A.; da Silva, Lorenzo Rolim; Coan, Ana Carolina (September 12, 2018). "Potential Clinical Benefits of CBD-Rich Cannabis Extracts Over Purified CBD in Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Observational Data Meta-analysis". Frontiers in Neurology. 9. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00759. ISSN 1664-2295. PMC 6143706. PMID 30258398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Further reading

- Williams, Alex (October 27, 2018). "Why Is CBD Everywhere?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.