Shanghai

Shanghai

上海 | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Shanghai · 上海市 | |

A view of the Pudong skyline | |

| |

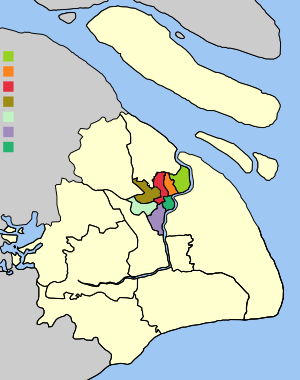

Location of Shanghai Municipality within China | |

| Country | |

| Settled | 5th–7th century |

| Incorporated - Town | 751 |

| - County | 1292 |

| - Municipality | July 7, 1927 |

| Divisions - County-level - Township-level | 18 districts, 1 county 220 towns and villages |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • CPC Municipal Sec. | Yu Zhengsheng |

| • Mayor | Han Zheng |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 7,037 km2 (2,717 sq mi) |

| • Land | 6,340 km2 (2,450 sq mi) |

| • Water | 679 km2 (262 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 5,299 km2 (2,046 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Population (2009)[4] | |

• Municipality | 19,210,000 |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard Time) |

| Postal code | 200000 – 202100 |

| Area code | 21 |

| GDP[5] | 2009 |

| - Total | CNY 1.49 trillion US$ 218 billion (8th) |

| - Per capita | CNY 77,564 US$ 11,361 (1st) |

| - Growth | |

| HDI (2006) | 0.917 (1st) |

| License plate prefixes | 沪A, B, D, E, F,G ,H, J 沪C (outer suburbs) |

| City flower | Yulan magnolia |

| Website | www.shanghai.gov.cn |

| Shanghai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 上海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu | Zaonhe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | above sea or on sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shanghai (Chinese: 上海; pinyin: Shànghǎi; Shanghainese: Zånhae; Mandarin pronunciation: [ʂɑŋ˥˩xaɪ̯˩˧]) is a metropolis in eastern China and a direct-controlled municipality of the People's Republic of China. Located at the middle part of the coast of mainland China, it sits at the mouth of the Yangtze.

Originally a fishing and textiles town, Shanghai grew to importance in the 19th century due to its favorable port location and as one of the cities opened to foreign trade by the 1842 Treaty of Nanking.[6] The city flourished as a center of commerce between east and west, and became a multinational hub of finance and business by the 1930s.[7] After 1990, the economic reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping resulted in intense re-development and financing in Shanghai, and in 2005 Shanghai became the world's largest cargo port.[8]

The city is a tourist destination renowned for its historical landmarks such as the Bund and City God Temple, and its modern and ever-expanding Pudong skyline including the Oriental Pearl Tower. Today, Shanghai is the largest center of commerce and finance in mainland China, and has been described as the "showpiece" of the world's fastest-growing major economy.[9]

Etymology

The two Chinese characters in the name "Shanghai", (上, shàng; and 海, hǎi) literally mean "high, top, up, on, or above" and "sea". The earliest occurrence of this name dates from the Song Dynasty (11th century), at which time there was already a river confluence and a town with this name in the area. There are disputes as to how the name should be interpreted, but official local histories have consistently said that it means "the upper reaches of the sea". Due to the changing coastline, Chinese historians have concluded that in the Tang Dynasty Shanghai was literally on the sea, hence the origin of the name.[10] Another reading, especially in Mandarin, also suggests the sense of "go onto the sea," which is consistent with the seaport status of the city. A more poetic name for Shanghai switches the order of the two characters, Hǎishàng (海上), and is often used for terms related to Shanghainese art and culture.

Shanghai is commonly abbreviated in Chinese as Hù (沪). The single character Hu (沪) appears on all motor vehicle license plates issued in Shanghai today. This is derived from Hu Du (沪渎), the name of an ancient fishing village that once stood at the confluence of Suzhou Creek and the Huangpu River back in the Tang Dynasty.[10] The character Hu is often combined with that for Song, as in Wusong Kou, Wu Song River, and Songjiang to form the nickname Song Hu. For example, the Japanese attack on Shanghai in August 1937 is commonly called the Song Hu Battle. Another early name for Shanghai was Hua Ting, now just the name of a four star hotel in the city.[10] One other commonly used nickname Shēn (申) is derived from the name of Chunshen Jun (春申君), a nobleman and locally-revered hero of the Chu Kingdom in the 3rd century BC whose territory included the Shanghai area. Sports teams and newspapers in Shanghai often use the character Shēn (申) in their names. Shanghai is also commonly called Shēnchéng (申城, "City of Shēn"). The city has also had various nicknames in English, including "Paris of the East".

History

During the Song Dynasty (AD 960–1279) Shanghai was upgraded in status from a village (cun) to a market town (zhen) in 1074, and in 1172 a second sea wall was built to stabilize the ocean coastline, supplementing an earlier dike.[11] From the Yuan Dynasty in 1292 until Shanghai officially became a city for the first time in 1297, the area was designated merely as a county (xian) administered by the Songjiang prefecture.[12]

Two important events helped promote Shanghai's development in the Ming Dynasty. A city wall was built for the first time during in 1554, in order to protect the town from raids by Japanese pirates. It measured 10 meters high and 5 kilometers in circumference.[13] During the Wanli reign (1573–1620), Shanghai received an important psychological boost from the erection of a City God Temple (Cheng Huang Miao) in 1602. This honor was usually reserved for places with the status of a city, such as a prefectural capital (fu), and was not normally given to a mere county town (zhen) like Shanghai. The honor was probably a reflection of the town's economic importance, as opposed to its low political status.[13]

During the Qing Dynasty, Shanghai became the most important sea port in the whole Yangtze Delta region. This was a result of two important central government policy changes. First of all, Emperor Kangxi (1662–1723) in 1684 reversed the previous Ming Dynasty prohibition on ocean going vessels, a ban that had been in force since 1525. Secondly, Emperor Yongzheng in 1732 moved the customs office (hai guan) for Jiangsu province from the prefectural capital of Songjiang city to Shanghai, and gave Shanghai exclusive control over customs collections for the foreign trade of all Jiangsu province. As a result of these two critical decisions, Professor Linda Cooke Johnson has concluded that by 1735 Shanghai had become the major trade port for all of the lower Yangzi River region, despite still being at the lowest administrative level in the political hierarchy.[14]

The importance of Shanghai grew radically in the 19th century, as the city's strategic position at the mouth of the Yangtze River made it an ideal location for trade with the West. During the First Opium War (1839–1842), British forces temporarily held Shanghai. The war ended with the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, opened the treaty ports, Shanghai included, for international trade. The Treaty of the Bogue signed in 1843, and the Sino-American Treaty of Wangsia signed in 1844 together allowed foreign nations to visit and trade on Chinese soil, the start of the foreign concessions.

In 1854 the Shanghai Municipal Council was created to manage the foreign settlements. In 1860-1862, during a civil war Shanghai had been invaded two times. In 1863, the British settlement, located to the south of Suzhou creek (Huangpu district), and the American settlement, to the north of Suzhou creek (Hongkou district), joined in order to form the International Settlement. The French opted out of the Shanghai Municipal Council, and maintained its own French Concession, located to the south of the International Settlement, which still exists today as a popular attraction. Citizens of many countries and all continents came to Shanghai to live and work during the ensuing decades; those who stayed for long periods — some for generations — called themselves "Shanghailanders".[15] In the 1920s and 1930s, almost 20,000 so-called White Russians and Russian Jews fled the newly-established Soviet Union and took up residence in Shanghai. These Shanghai Russians constituted the second-largest foreign community. By 1932, Shanghai had become the world's fifth largest city and home to 70,000 foreigners.[16] In the 1930s, some 30,000 Jewish refugees from Europe arrived in the city.[17]

The Sino-Japanese War concluded with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which elevated Japan to become another foreign power in Shanghai. Japan built the first factories in Shanghai, which were soon copied by other foreign powers. Shanghai was then the most important financial center in the Far East.

Under the Republic of China (1911–1949), Shanghai's political status was finally raised to that of a municipality on July 14, 1927. Although the territory of the foreign concessions was excluded from their control, this new Chinese municipality still covered an area of 828.8 square kilometers, including the modern-day districts of Baoshan, Yangpu, Zhabei, Nanshi, and Pudong. Headed by a Chinese mayor and municipal council, the new city governments first task was to create a new city center in Jiangwan town of Yangpu district, outside the boundaries of the foreign concessions. This new city center was planned to include a public museum, library, sports stadium, and city hall.[18]

The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed Shanghai on 28 January 1932, nominally in an effort to crush down Chinese student protests of the Manchurian Incident and the subsequent Japanese occupation of northeast China. The Chinese fought back in what was known as the January 28 Incident. The two sides fought to a standstill and a ceasefire was brokered in May. The Battle of Shanghai in 1937 resulted in the occupation of the Chinese administered parts of Shanghai outside of the International Settlement and the French Concession. The International Settlement was occupied by the Japanese on 8 December 1941 and remained occupied until Japan's surrender in 1945. According to historian Zhiliang Su, at least 149 "comfort houses" for sexual slaves were established in Shanghai during the occupation.[19]

On 27 May 1949, the Communist People's Liberation Army took control of Shanghai, which was one of only three former Republic of China (ROC) municipalities not merged into neighbouring provinces over the next decade (the others being Beijing and Tianjin). Shanghai underwent a series of changes in the boundaries of its subdivisions, especially in the next decade. After 1949, most foreign firms moved their offices from Shanghai to Hong Kong, as part of an exodus of foreign investment due to the Communist victory.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Shanghai became an industrial center and center for revolutionary leftism. Yet, even during the most tumultuous times of the Cultural Revolution, Shanghai was able to maintain high economic productivity and relative social stability. In most of the history of the People's Republic of China (PRC), Shanghai has been the largest contributor of tax revenue to the central government compared with other Chinese provinces and municipalities. This came at the cost of severely crippling Shanghai's infrastructure and capital development. Its importance to China's fiscal well-being also denied it economic liberalizations that were started in the far southern provinces such as Guangdong during the mid-1980s. At that time, Guangdong province paid nearly no taxes to the central government, and thus was perceived as fiscally expendable for experimental economic reforms. Shanghai was finally permitted to initiate economic reforms in 1991, starting the huge development still seen today and the birth of Lujiazui in Pudong.

Geography and climate

Shanghai sits on the Yangtze River Delta on China's eastern coast, and is roughly equidistant from Beijing and Hong Kong. The municipality as a whole consists of a peninsula between the Yangtze and Hangzhou Bay, China's third largest island Chongming, and a number of smaller islands. It is bordered on the north and west by Jiangsu Province, on the south by Zhejiang Province, and on the east by the East China Sea. The city proper is bisected by the Huangpu River, a tributary of the Yangtze. The historic center of the city, the Puxi area, is located on the western side of the Huangpu, while a new financial district, Pudong, has developed on the eastern bank.

The vast majority of Shanghai's 6,218 km2 (2,401 sq mi) land area is flat, apart from a few hills in the southwest corner, with an average elevation of 4 m (13 ft).[20] The city's location on the flat alluvial plain has meant that new skyscrapers must be built with deep concrete piles to stop them sinking into the soft ground. The highest point is at the peak of Dajinshan Island at 103 m (338 ft).[21] The city has many rivers, canals, streams and lakes and is known for its rich water resources as part of the Taihu drainage area.

Public awareness of the environment is growing, and the city is investing in a number of environmental protection projects. A 10-year, US$1 billion cleanup of Suzhou Creek, which runs through the city center, was expected to be finished in 2008,[22] and the government also provides incentives for transportation companies to invest in LPG buses and taxis. Air pollution in Shanghai is low compared to other Chinese cities such as Beijing, but the rapid development over the past decades means it is still high on worldwide standards, comparable to Los Angeles.[23]

Shanghai has a humid subtropical climate (Koppen climate classification Cfa) and experiences four distinct seasons. In winter, cold northerly winds from Siberia can cause nighttime temperatures to drop below freezing, although most years there are only one or two days of snowfall. Summer in Shanghai is very warm and humid, with occasional downpours or freak thunderstorms. The city is also susceptible to typhoons, none of which in recent years has caused considerable damage.[24] The most pleasant seasons are Spring, although changeable, and Autumn, which is generally sunny and dry. Shanghai experiences on average 1,878 hours of sunshine per year, with the hottest temperature ever recorded at 40 °C (104 °F), and the lowest at −12 °C (10.4 °F).[25] The average number of rainy days is 112 per year, with the wettest month being June.[25] The average frost-free period is 276 days.[20]

| Climate data for Shanghai (Xujiahui), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

40.9 (105.6) |

40.8 (105.4) |

38.2 (100.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.6 (90.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.2 (2.84) |

65.0 (2.56) |

97.3 (3.83) |

84.2 (3.31) |

91.0 (3.58) |

224.9 (8.85) |

163.2 (6.43) |

225.9 (8.89) |

131.5 (5.18) |

69.6 (2.74) |

61.4 (2.42) |

50.4 (1.98) |

1,336.6 (52.61) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10.6 | 10.4 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 14.3 | 12.2 | 12.7 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 130.7 |

| Average snowy days | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 5.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 71 | 70 | 69 | 70 | 79 | 76 | 76 | 74 | 70 | 71 | 69 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.3 | 119.9 | 128.5 | 148.5 | 169.8 | 130.9 | 190.8 | 185.7 | 167.5 | 161.4 | 131.1 | 127.4 | 1,775.8 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration (sun 1981–2010)[26][27][28]all-time extreme temperature[29] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Shanghai (Minhang District), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.3 (99.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

36.2 (97.2) |

34.1 (93.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.9 (17.8) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.4 (2.77) |

65.4 (2.57) |

95.4 (3.76) |

82.5 (3.25) |

93.2 (3.67) |

207.3 (8.16) |

148.0 (5.83) |

187.1 (7.37) |

118.1 (4.65) |

68.4 (2.69) |

59.4 (2.34) |

50.3 (1.98) |

1,245.5 (49.04) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10.9 | 10.2 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 14.5 | 11.7 | 12.4 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 129.7 |

| Average snowy days | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 4.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 73 | 74 | 72 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.8 | 117.9 | 143.8 | 168.1 | 176.8 | 131.2 | 209.4 | 202.3 | 163.7 | 162.1 | 131.1 | 129.7 | 1,850.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 36 | 37 | 39 | 43 | 41 | 31 | 49 | 50 | 45 | 46 | 42 | 41 | 42 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[30][31][32] | |||||||||||||

Politics

Shanghai has been a political hub of China since the 20th century. The 1st National Congress of the Communist Party of China was held in Shanghai. In addition, many of China's top government officials in Beijing are known to have risen in Shanghai in the 1980s on a platform that was critical of the extreme leftism of the Cultural Revolution, giving them the tag "Shanghai Clique" during the 1990s. Many observers of Chinese politics view the more right-leaning Shanghai Clique as an opposing and competing faction of the current Chinese administration under President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. Shanghai's top jobs, the Party Chief and the position of Mayor, have always been prominent on a national scale. Four secretaries of municipal Party committee or mayors from Shanghai eventually went on to take prominent Central Government positions, including former President Jiang Zemin, former Premier Zhu Rongji, and current Vice-President Xi Jinping. The top administrative jobs are always appointed directly by the Central Government.[citation needed]

The current Shanghai government under Mayor Han Zheng has openly advocated transparency in the city's government. However, in previous years a complicated system of relationships between Shanghai's government, banks, and other civil institutions has been under scrutiny for corruption, motivated by faction politics in Beijing; these allegations from Beijing did not go anywhere until late 2006. Since Jiang's departure from office there has been a significant amount of clash between the local government in Shanghai and the Central People's Government, an evolving example of de facto Chinese federalism. The Shanghai government looks after almost all of the city's economic interests without interference from Beijing.[citation needed]

By 2006, Shanghai's actual level of autonomy has arguably surpassed that of any autonomous regions, raising alarm bells in Beijing. In September 2006, the Shanghai Communist Party Secretary Chen Liangyu, a native of Ningbo and often clashing with central government officials, along with a number of his followers, were removed from their positions after a probe into the city's pension fund. Over a hundred investigators, sent by the Central Government, reportedly uncovered clues of money diversion from the city's pension fund to unapproved loans and investments. Chen's abrupt removal is viewed by many Chinese as a political manoeuvre by President Hu Jintao to further secure his power in the country, and retain administrative centralism. In March 2007 the central government appointed Xi Jinping, who is not a Shanghai native, to become the Party Secretary, the most powerful office in the city. Xi would eventually be transferred to work for the central government in Beijing and was replaced by Yu Zhengsheng in November 2007.[citation needed]

Administrative divisions

Shanghai is administratively equal to a province and is divided into 18 county-level divisions: 17 districts and one county. Even though every district has its own urban core, the real city center is between Bund to the east, Nanjing Rd to the north, Old City Temple and Huaihai Road to the south. Prominent central business areas include Lujiazui on the east bank of the Huangpu River, and The Bund and Hongqiao areas in the west bank of the Huangpu River. The city hall and major administration units are located in Huangpu District, which also serve as a commercial area, including the famous Nanjing Road. Other major commercial areas include Xintiandi and the classy Huaihai Road (or Avenue Joffre before Liberation) in Luwan district and Xujiahui (which used to be translated into English as Zikawei, reflecting the Shanghainese pronunciation) in Xuhui District. Many universities in Shanghai are located in residential areas of Yangpu District and Putuo District.

Nine of the districts govern Puxi (literally Huangpu River west), or the older part of urban Shanghai on the west bank of the Huangpu River. These nine districts are collectively referred to as Shanghai Proper (上海市区) or the core city (市中心):

- Huangpu District (simplified Chinese: 黄浦区; traditional Chinese: 黃浦區; pinyin: Huángpǔ Qū)

- Luwan District (卢湾区 Lúwān Qū)

- Xuhui District (徐汇区 Xúhuì Qū)

- Changning District (长宁区 Chángníng Qū)

- Jing'an District (静安区 Jìng'ān Qū)

- Putuo District (普陀区 Pǔtuó Qū)

- Zhabei District (闸北区 Zháběi Qū)

- Hongkou District (虹口区 Hóngkǒu Qū)

- Yangpu District (杨浦区 Yángpǔ Qū)

Pudong (literally Huangpu River east), or the newer part of urban and suburban Shanghai on the east bank of the Huangpu River, is governed by:

- Pudong New District (浦东新区 Pǔdōng Xīn Qū) — Chuansha County until 1992, merged with Nanhui District in 2009

Seven of the districts govern suburbs, satellite towns, and rural areas further away from the urban core:

- Baoshan District (宝山区 Bǎoshān Qū) — Baoshan County until 1988

- Minhang District (闵行区 Mǐnháng Qū) — Shanghai County until 1992

- Jiading District (嘉定区 Jiādìng Qū) — Jiading County until 1992

- Jinshan District (金山区 Jīnshān Qū) — Jinshan County until 1997

- Songjiang District (松江区 Sōngjiāng Qū) — Songjiang County until 1998

- Qingpu District (青浦区 Qīngpǔ Qū) — Qingpu County until 1999

- Fengxian District (奉贤区 Fèngxián Qū) — Fengxian County until 2001

Chongming Island, an island at the mouth of the Yangtze, is governed by:

- Chongming County (崇明县 Chóngmíng Xiàn)

As of 2003, these county-level divisions are further divided into the following 220 township-level divisions: 114 towns, 3 townships, 103 subdistricts. Those are in turn divided into the following village-level divisions: 3,393 neighborhood committees and 2,037 village committees.

Economy

Shanghai is often regarded as the center of finance and trade in mainland China. Modern development began with the economic reforms in 1992, a decade later than many of the Southern Chinese provinces, but since then Shanghai quickly overtook those provinces and maintained its role as the business center in mainland China. Shanghai also hosts the largest share market in mainland China.

The non-state sector has grown to generate 42 percent of Shanghai's GDP, while the reformed state-sector generates 57.5 percent of GDP.[33] Since 2005, Shanghai has ranked first of the world's busiest cargo ports throughout, handling a total of 560 million tons of cargo in 2007. Shanghai container traffic has surpassed Hong Kong to become the second busiest port in the world, behind Singapore.[34] Shanghai and Hong Kong are rivaling to be the economic center of the Greater China region. Hong Kong has the advantage of a stronger legal system, international market integration, superior economic freedom, greater banking and service expertise, lower taxes, and a fully-convertible currency. Shanghai has stronger links to both the Chinese interior and the central government, and a stronger base in manufacturing and technology. Shanghai has increased its role in finance, banking, and as a major destination for corporate headquarters, fueling demand for a highly educated and modernized workforce. Shanghai has recorded a double-digit growth for 15 consecutive years since 1992. In 2008, Shanghai's nominal GDP posted a 9.7% growth to 1.37 trillion yuan. The Shanghai Stock Exchange is the world's fastest growing, with the Shanghai Composite Index growing 130% in 2006.[35]

As in many other areas in China, Shanghai is undergoing a building boom. In Shanghai the modern architecture is notable for its unique style, especially in the highest floors, with several top floor restaurants which resemble flying saucers. For a gallery of these unique architecture designs, see Shanghai (architecture images). The bulk of Shanghai buildings being constructed today are high-rise apartments of various height, color and design. There is now a strong focus by city planners to develop more "green areas" (public parks) among the apartment complexes in order to improve the quality of life for Shanghai's residents, quite in accordance to the "Better City - Better Life" theme of Shanghai's Expo 2010.

Industrial zones in Shanghai include Shanghai Hongqiao Economic and Technological Development Zone, Jinqiao Export Economic Processing Zone, Minhang Economic and Technological Development Zone, and Shanghai Caohejing High and New Technological Development Zone (see List of economic and technological development zones in Shanghai).

Logistics Park in Shanghai include BLOGIS Park (Shanghai)[36] and GLP Park Lingang.[37]

Demographics

The population of Shanghai is 19,213,200.[4] Based on total administrative area population, Shanghai is the third largest of the four direct-controlled municipalities of the People's Republic of China, after Chongqing[38] and Beijing[39]. In the PRC, a direct-controlled municipality (直辖市 in pinyin: zhíxiáshì) is a city with equal status to a province. The 2000 census put the population of Shanghai Municipality at 16.738 million, including the migrant population, which made up 3.871 million.[citation needed] Since the 1990 census the total population had increased by 3.396 million, or 25.5%. Males accounted for 51.4%, females for 48.6% of the population. 12.2% were in the age group of 0–14, 76.3% between 15 and 64 and 11.5% were older than 65.[citation needed] As of 2008, the population of long-term residents reached 18.88 million, including an officially registered permanent population of 13.71 million, and 4.79 million of registered long-term migrants from other provinces, many from Anhui, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang Provinces.[citation needed] According to the Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau, there were 133,340 foreigners in Shanghai in 2007.[40] In addition, there are a large number of people from Taiwan for business (estimates vary from 350,000 to 700,000). By 2009, the South Korean communities in Shanghai also increased to more than 70,000.[41] The average life expectancy in 2006 was 80.97 years, 78.67 for men and 82.29 for women.[42] Average annual disposable income of Shanghai residents, based on the first three quarters of 2009, is 21,871 RMB.[43]

Languages

Most Shanghainese residents are the descendants of immigrants from the two adjacent provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang who moved to Shanghai in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, regions that generally also speak Wu Chinese. In the past decades, many migrants from other areas of China have come to Shanghai for work. They often cannot speak the local dialect and therefore use Mandarin as a lingua franca.

The vernacular language is Shanghainese, a dialect of Wu Chinese, while the official language is Standard Mandarin. The local dialect is mutually unintelligible with Mandarin, and is an inseparable part of the Shanghainese identity. The modern Shanghainese dialect is based on the Suzhou dialect of Wu, the prestige dialect of Wu spoken within the Chinese city of Shanghai prior to the modern expansion of the city, the Ningbo dialect of Wu, and the dialect of Shanghai's traditional areas now within the Hongkou, Baoshan and Pudong districts, which is simply called "Bendihua", or "the local dialect". It is influenced to a lesser extent by the dialects of other nearby regions from which large numbers of people have migrated to Shanghai since the 20th century. Nearly all Shanghainese under the age of 40 can speak Mandarin fluently. Fluency in foreign languages is unevenly distributed. Most senior residents who received a university education before the revolution, and those who worked in foreign enterprises, can speak English. Those under the age of 26 have had contact with English since primary school, as English is taught as a mandatory course starting from the first grade.

Religion

Due to its cosmopolitan history, Shanghai has a rich blend of religious heritage as shown by the religious buildings and institutions still scattered around the city. Taoism has a presence in Shanghai in the form of several temples, including the City God Temple, at the heart of the old city, and a temple dedicated to the Three Kingdoms general Guan Yu. The Wenmiao is a temple dedicated to Confucius. Buddhism has had a presence in Shanghai since ancient times. Longhua temple, the largest temple in Shanghai, and Jing'an Temple, were first founded in the Three Kingdoms period. Another important temple is the Jade Buddha Temple, which is named after a large statue of Buddha carved out of jade in the temple. In recent decades, dozens of modern temples have been built throughout the city.

Shanghai is also an important center of Christianity in China. Churches belonging to various denominations are found throughout Shanghai and maintain significant congregations. Among Catholic churches, St Ignatius Cathedral in Xujiahui is one of the largest, while She Shan Basilica is the only active pilgrimage site in China. Shanghai has the highest Catholic percentage in Mainland China (2003).[44] The city is also home to Muslim, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox communities. A predominant religion in Shanghai is Mahayana Buddhism, and Taoism is also followed by many Shanghai residents.

Education

While Beijing and Hong Kong are considered the educational centers of China, Shanghai is also home to some of the country's most prestigious universities, including Fudan University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Tongji University.

Transport

Shanghai has an extensive public transport system, largely based on buses, trolleybuses, taxis, and a rapidly expanding metro system. All of these public transport tools can be accessed using the Shanghai Public Transportation Card, which uses radio frequencies so the card does not have to physically touch the scanner.

The Shanghai Metro rapid-transit system and elevated light rail has eleven lines at present and extends to every core urban district as well as neighbouring suburban districts such as Songjiang, Minhang and Jiading. It is one of the fastest-growing metro systems in the world — the first line opened in 1995,[45] and as of 2010[update], the Shanghai Metro is the 9th busiest system worldwide and the largest in the world by length (420 km). Shanghai also has the world's most extensive bus system with nearly one thousand bus lines, operated by numerous transportation companies. Not all of Shanghai's bus routes are numbered—some have names exclusively in Chinese.[46] Bus fares are usually ¥1, ¥1.5 or ¥2, sometimes higher, while Metro fares run from ¥3 to ¥10 depending on distance.

Taxis in Shanghai are plentiful and government regulation has set taxi fares at an affordable rate for the average resident—¥12 for 3 km, ¥16 after 23:00, and 2.4RMB/km thereafter. Before the 1990s, bicycling was the most ubiquitous form of transport in Shanghai, but the city has since banned bicycles on many of the city's main roads to ease congestion. However, many streets have bicycle lanes and intersections are monitored by "Traffic Assistants" who help provide for safe crossing. Further, the city government has pledged to add 180 km of cycling lanes over the next few years. It is worth noting that a number of the main shopping and tourist streets, Nanjing Road and Huaihai Road do not allow bicycles.

With rising disposable incomes, private car ownership in Shanghai has also been rapidly increasing in recent years. The number of cars is limited, however, by the number of available number plates available at public auction. Since 1998 the number of new car registrations is limited to 50,000 vehicles a year.[47]

In cooperation with the Shanghai municipality and the Shanghai Maglev Transportation Development Co. (SMT), German Transrapid constructed the first commercial high speed Maglev railway in the world in 2002, from Shanghai's Longyang Road subway station in Pudong to Pudong International Airport. Commercial operation started in 2003. The 30 km trip takes 7 minutes and 21 seconds and reaches a maximum speed of 431 km/h (267.8 mph). Normal operating speeds usually reach 431 km/h, but during a test run, the Maglev has been shown to reach a top speed of 501 km/h.

Two railways intersect in Shanghai: Jinghu Railway (Beijing–Shanghai) Railway passing through Nanjing, and Huhang Railway (Shanghai–Hangzhou). Shanghai is served by two main railway stations, Shanghai Railway Station and Shanghai South Railway Station. Express service to Beijing through Z-series trains is fairly convenient. A maglev train route to Hangzhou (Shanghai-Hangzhou Maglev Train) might begin construction in 2010. A high-speed railroad to Beijing is also in the works.

More than six national expressways (prefixed with "G") from Beijing and from the region around Shanghai connect to the city. Shanghai itself has six toll-free elevated expressways (skyways) in the urban core and 18 municipal expressways (prefixed with "A"). There are ambitious plans to build expressways connecting Shanghai's Chongming Island with the urban core. For a city of Shanghai's size, road traffic is still fairly smooth and convenient but getting more congested as the number of cars increases rapidly.

Shanghai has two commercial airports: Hongqiao International and Pudong International,[48] the latter of which has the third highest traffic in China, following Beijing Capital International Airport and Hong Kong International Airport. Pudong International handles more international traffic than Beijing Capital however, with over 17.15 million international passengers handled in 2006 compared to the latter's 12.6 million passengers.[49] Hongqiao mainly serves domestic routes, with a few city-to-city flights to Tokyo's Haneda Airport and Seoul's city airport. Hongqiao airport is about 10 kilometers west of the downtown. One of the airport's advantages is it is much closer to the city center than Pudong airport.

Architecture

Shanghai has a rich collection of buildings and structures of various architectural styles. The Bund, located by the bank of the Huangpu River, contains a rich collection of early 20th century architecture, ranging in style from neoclassical HSBC Building to the art deco Sassoon House. A number of areas in the former foreign concessions are also well preserved, most notably the French Concession. Shanghai has one of the worlds largest number of Art Deco buildings as a result of the construction boom during the 1920s and 30s. One of the most famous architects working in Shanghai was László Hudec, a Hungarian architect who lived in the city between 1918-1947. Some of his most notable Art Deco buildings include the Park Hotel and the Grand Theater. Other prominent architects who contributed to the Art Deco style are Parker & Palmer who designed the Peace Hotel, Metropole Hotel and the Broadway Mansions, and Austrian architect GH Gonda who designed the Capital Theatre.

Despite rampant redevelopment, the old city still retains some buildings of a traditional style, such as the Yuyuan Garden, an elaborate traditional garden in the Jiangnan style.

In recent years, a large number of architecturally distinctive, even eccentric, skyscrapers have sprung up throughout Shanghai. Notable examples of contemporary architecture include the Shanghai Museum, Shanghai Grand Theatre in the People's Square precinct and Shanghai Oriental Arts Center.

One uniquely Shanghainese cultural element is the shikumen (石库门) residences, which are two or three-story townhouses, with the front yard protected by a high brick wall. Each residence is connected and arranged in straight alleys, known as a lòngtang (弄堂), pronounced longdang in Shanghainese. The entrance to each alley is usually surmounted by a stylistic stone arch. The whole resembles terrace houses or townhouses commonly seen in Anglo-American countries, but distinguished by the tall, heavy brick wall in front of each house. The name "shikumen" literally means "stone storage door", referring to the strong gateway to each house.

The shikumen is a cultural blend of elements found in Western architecture with traditional Lower Yangtze (Jiangnan) Chinese architecture and social behavior. All traditional Chinese dwellings had a courtyard, and the shikumen was no exception. Yet, to compromise with its urban nature, it was much smaller and provided an "interior haven" to the commotions in the streets, allowing for raindrops to fall and vegetation to grow freely within a residence. The courtyard also allowed sunlight and adequate ventilation into the rooms.

The city also has some beautiful examples of Soviet neoclassical architecture. These buildings were mostly erected during the period from the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 until the Sino-Soviet Split in the late 1960s. During this decade, large numbers of Soviet experts poured into China to aid the country in the construction of a communist state, some of them were architects. Examples of Soviet neoclassical architecture in Shanghai include what is today the Shanghai International Exhibition Center. Beijing, the nation's capital, displays an even greater array of this particular type of architecture.

The Pudong district of Shanghai displays a wide range of supertall skyscrapers. The most prominent examples include the Jin Mao Tower and the taller Shanghai World Financial Center, which at 492 metres tall is the tallest skyscraper in mainland China and ranks third in the world. The distinctive Oriental Pearl Tower, at 468 metres, is located nearby toward downtown Shanghai. Its lower sphere is now available for living quarters, at very high prices. Another tall highrise in the Pudong area of Shanghai is the newly finished Development Tower. It stands at 269 meters.[50]

Also in Pudong, a third supertall skyscraper topping the other Shanghai buildings called the Shanghai Tower is under construction. With a height of 632 metres (2074 feet), the building will have 127 floors upon planned completion in 2014.

Culture

Because of Shanghai's status as the cultural and economic center of East Asia for the first half of the twentieth century, it is popularly seen as the birthplace of everything considered modern in China. It was in Shanghai, for example, that the first motor car was driven and the first train tracks and modern sewers were laid. It was also the intellectual battleground between socialist writers who concentrated on critical realism, which was pioneered by Lu Xun (zh:鲁迅), Mao Dun (zh:茅盾), Nien Cheng and famous French novel the Man's Fate, and the more "bourgeois", more romantic and aesthetically inclined writers, such as Shi Zhecun (zh:施蛰存), Shao Xunmei (邵洵美), Ye Lingfeng (葉靈鳳) and Eileen Chang (zh:张爱玲).

Besides literature, Shanghai was also the birthplace of Chinese cinema and theater. China’s first short film, The Difficult Couple (難夫難妻, Nanfu Nanqi, 1913), and the country’s first fictional feature film, An Orphan Rescues His Grandfather (孤兒救祖記, Gu'er jiu zuji, 1923) were both produced in Shanghai. These two films were very influential, and established Shanghai as the center of Chinese film-making. Shanghai’s film industry went on to blossom during the early Thirties, generating Marilyn Monroe-like stars such as Zhou Xuan. Another film star, Jiang Qing, went on to become Madame Mao Zedong. The talent and passion of Shanghainese filmmakers following World War II and the Communist revolution in China contributed enormously to the development of the Hong Kong film industry. Many aspects of Shanghainese popular culture ("Shanghainese Pops") were transferred to Hong Kong by the numerous Shanghainese emigrants and refugees after the Communist Revolution. The movie In the Mood for Love, which was directed by Wong Kar-wai (a native Shanghainese himself), depicts one slice of the displaced Shanghainese community in Hong Kong and the nostalgia for that era, featuring 1940s music by Zhou Xuan.

Shanghai boasts several museums of regional and national importance. The Shanghai Museum of art and history has one of the best collections of Chinese historical artifacts in the world, including important archaeological finds since 1949. The Shanghai Art Museum, located near People's Square, is a major art museum holding both permanent and temporary exhibitions. The Shanghai Natural History Museum is a large scale natural history museum. In addition, there is a variety of smaller, specialist museums, some housed in important historical sites such as the site of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea and the site of the First National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

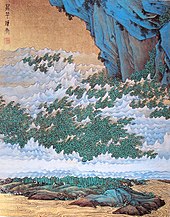

The Shanghai School (海上画派, Haishang Huapai, which is shortened to 海派, Haipai) is a very important Chinese school of traditional arts during the Qing Dynasty and the whole of the twentieth century. Under efforts of masters from this school, traditional Chinese art reached another climax and continued to the present in forms of the "Chinese painting" (中国画) or guohua (国画) for short. The Shanghai School challenged and broke the literati tradition of Chinese art, while also paying technical homage to the ancient masters and improving on existing traditional techniques. Members of this school were themselves educated literati who had come to question their very status and the purpose of art, and had anticipated the impending modernization of Chinese society. In an era of rapid social change, works from the Shanghai School were widely innovative and diverse, and often contained thoughtful yet subtle social commentary. The most well-known figures from this school are Qi Baishi (齊白石), Ren Xiong (任熊), Ren Yi (任伯年), Zhao Zhiqian (赵之谦), Wu Changshuo (吴昌硕), Sha Menghai (沙孟海, calligraphist), Pan Tianshou (潘天寿), Fu Baoshi (傅抱石) and Wang Zhen (Wang Yiting) (王震). In literature, the term was used in the 1930s by some May Fourth Movement intellectuals, notably Zhou Zuoren and Shen Congwen, as a derogatory label for the literature produced in Shanghai at the time. They argued that so-called Shanghai School literature was merely commercial and therefore did not advance social progress. This became known as the Jingpai (Beijing School) versus Haipai (Shanghai School) debate.

Songjiang School (淞江派) is a small painting school during the Ming Dynasty. It is commonly considered as a further development of the Wu School, or Wumen School (吴门画派), in the then cultural center of the region, Suzhou. Huating School (华亭派) was another important art school during the middle to late Ming Dynasty. Its main achievements were in traditional Chinese painting, calligraphy and poetry, and especially famous for its Renwen painting (人文画). Dong Qichang (董其昌) is one of the masters from this school.

Shanghai's parks offer some reprieve from the urban jungle. Due to the scarcity of play space for children, nearly all parks have a children's section. Zhongshan Gongyuan in Downtown Shanghai is famous for its monument of Chopin, the tallest statue dedicated to the composer in the world. Built in 1914 as Jessfield Park, it once contained the campus of St. John's University, Shanghai's first international college; today, it is known for its extensive rose and peony gardens, a large children's play area, and as the location of an important transfer station on the city's metro system. One of the newest is in the Xujiahui District, Xujiahui Gongyuan, built in 1999 on the former grounds of the Great Chinese Rubber Works Factory and the EMI Recording Studio (today's glamorous La Villa Rouge restaurant), with entrances at Zhaojiabang Lu and in the west at the intersection of Hengshang Lu and Yuqin Lu. The park has a man-made lake with a sky bridge running across the park, and offers a pleasant respite for Xujiahui shoppers.

Other Shanghainese cultural artifacts include the cheongsam (Shanghainese: zansae), a modernization of the traditional Chinese/Manchurian qipao (Chinese: 旗袍; fitting. This contrasts sharply with the traditional qipao which was designed to conceal the figure and be worn regardless of age. The cheongsam went along well with the western overcoat and the scarf, and portrayed a unique East Asian modernity, epitomizing the Shanghainese population in general. As Western fashions changed, the basic cheongsam design changed, too, introducing high-necked sleeveless dresses, bell-like sleeves and, the black lace frothing at the hem of a ball gown. By the 1940s, cheongsams came in transparent black, beaded bodices, matching capes and even velvet. And later, checked fabrics became also quite common. The 1949 Communist Revolution ended the cheongsam and other fashions in Shanghai. However, the Shanghainese styles have seen a recent revival as stylish party dresses. The fashion industry has been rapidly revitalizing in the past decade, there is on average one fashion show per day in Shanghai today. Like Shanghai's architecture, local fashion designers strive to create a fusion of western and traditional designs, often with innovative if uncontroversial results.

Shanghai has hosted a number of world events, including the 2007 Summer Special Olympics and a Live Earth concert.[51] The Shanghai International Film Festival is annually held in the city. Shanghai is also home to a number of professional sports teams, including Shanghai Shenhua of the Chinese Super League, the Shanghai Sharks of the Chinese Basketball Association, China Dragon of Asia League Ice Hockey and the Shanghai Golden Eagles of the China Baseball League. The city has also hosted the Formula One Chinese Grand Prix at the Shanghai International Circuit every year since 2004. The city is the host of the Expo 2010 World's Fair between May 1 and October 2010.

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Shanghai is twinned with:

See also

- List of attractions in Shanghai

- List of universities and colleges in Shanghai

- List of fiction set in Shanghai

- List of films set in Shanghai

- List of economic and technological development zones in Shanghai

- Shanghai cuisine

- Shanghai International Group

- List of cities proper by population

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Land Area". Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "Water Resources". Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "Topographic Features". Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ a b "Shanghai's permanent population approaches 20 mln". People's Daily.

- ^ "Shanghai posts 8.2% growth in GDP". Shanghai Daily.

- ^ Mackerras, Colin (2001). The New Cambridge Handbook of Contemporary China. Cambridge University Press. p. 242. ISBN 0521786746.

- ^ "A Glimpse at 1930s Shanghai". Yoran Beisher. 2003-09-24. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "Shanghai now the world's largest cargo port". Asia Times Online. 2006-01-07. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "Shanghai: China's capitalist showpiece". BBC News. 2008-05-21. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

"Of Shanghai... and Suzhou". The Hindu Business Line. 2003-01-27. Retrieved 2008-03-20. - ^ a b c Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, pp.8-9.

- ^ Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, p.9.

- ^ Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, p.9, pp.11-12, p.34.

- ^ a b Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, p.10.

- ^ Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, pp.10-11.

- ^ Shanghai: Paradise for adventurers. CBC – TV. Legendary Sin Cities.

- ^ "All About Shanghai. Chapter 4 – Population ". Tales of Old Shanghai.

- ^ "Shanghai Sanctuary". TIME. July 31, 2008.

- ^ Danielson, Eric N., Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta, 2004, p.34.

- ^ « 149 comfort women houses discovered in Shanghai », Xinhua, 16 June 2005.

- ^ a b "Shanghai Statistical Yearbook". Shanghai Municipal Government. 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "Shanghai travel guide - Geography". TravelChinaGuide.com. 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "Suzhou Creek clean-up on track". People's Daily Online. 2006-12-07. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Environmental Protection in China's Wealthiest City". The American Embassy in China. July 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "1.6m flee Shanghai typhoon". The Daily Telegraph. 2007-09-19. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ a b "BBC - Average Conditions Shanghai, China". BBC. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集" (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 2024-09-22.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集 (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ CMA台站气候标准值(1991-2020) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ 上海时隔两年再发布高温红警:徐家汇站最高气温达40℃ (in Chinese). The Paper (澎湃新闻). Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ "shanghai". shanghai. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ ["http://transport.tdctrade.com/content.aspx?data=Logistics_content_en&contentid=1004574" "Shanghai port TEU throughput ranks 2nd largest in the world"]. Hong Kong Trade Development Council.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Shanghai Stock Exchange announces 2007 strategy". Hong Kong Trade Development Council. 2007-03-06. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ "RightSite.asia". RightSite.asia. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "RightSite.asia". RightSite.asia. 2004-11-20. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ "Chongqing Municipal Government - Demographics".

- ^ "Beijing's population exceeds 22 million". National Population and Family Planning Commission of China. 2010-03-02.

- ^ "Expat Evolution: Is Shanghai's full-package expat going extinct?". City Weekend Guide.

- ^ "在华居住韩国人达百万 北京人数最多达二十万". Xinhuanet.com. 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ "Shanghai Basic Facts". Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau.

- ^ "Average income hits 21,871 yuan". Shanghai Daily.

- ^ According to Johnstone, Patrick; Schirrmacher, Thomas (2003). Gebet für die Welt. Hänssler. ISBN 978-0-8133-4275-7.

- ^ "Shanghai Subway - Metro". UrbanRail.Net. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Personal Cars and China (2003)".

- ^ Sperling, Daniel and Deborah Gordon (2009), Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 219–220, ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7 . See on Chapter 8 Stimulating Chinese Innovation.

- ^ "Transportation". Shanghai Focus. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Pudong airport has most passengers from abroad (The Business Times: 9 January 2007)

- ^ Emporis GmbH. "One Lujiazui, Shanghai". Emporis.com. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ^ Collier, Robert (2007-07-08). "Warming strikes a note in China". SFGate.com. pp. A4. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ^ "Eight Cities/Six Ports: Yokohama's Sister Cities/Sister Ports". Yokohama Convention & Visitiors Bureau. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Staff, Hamburg und seine Städtepartnerschaften (Hamburg sister cities), Hamburg's official website [1], retrieved 2008-08-05

{{citation}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "International Relations of the City of Porto" (PDF). © 2006-2009 Municipal Directorateofthe PresidencyServices InternationalRelationsOffice. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ "Barcelona internacional - Ciutats agermanades" (in Spanish). © 2006-2009 Ajuntament de Barcelona. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=

Bibliography

- Danielson, Eric N. (2004). Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish/Times Editions. ISBN 981-232-578-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Elvin, Mark (1977). "Market Towns and Waterways: The County of Shanghai from 1480 to 1910," in The City in Late Imperial China, ed. by G. William Skinner. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Johnson, Linda Cooke (1995). Shanghai: From Market Town to Treaty Port. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Johnson, Linda Cooke (1993). Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China. Albany: State University of New York (SUNY).

- Horesh, Niv (2009). Shanghai's Bund and Beyond. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Erh,Deke and Johnston, Tess (2007). Shanghai Art Deco. Hong Kong: Old China Hand Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)