Hong Kong

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China 中華人民共和國香港特別行政區 | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "March of the Volunteers"[1] | |

| City flower Bauhinia blakeana (洋紫荊) | |

Location of Hong Kong | |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | Cantonese[3] |

| Official scripts[4] | English alphabet Traditional Chinese |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Special administrative region of China[a] |

| Leung Chun-ying | |

| Geoffrey Ma | |

| Carrie Lam | |

| John Tsang | |

| Rimsky Yuen | |

| Jasper Tsang | |

| Legislature | Legislative Council |

| History | |

| 26 January 1841 | |

| 29 August 1842 | |

| 18 October 1860 | |

| 1 July 1898 | |

| 25 December 1941 to 15 August 1945 | |

• Transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom | 1 July 1997 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,104 km2 (426 sq mi) (179th) |

• Water (%) | 4.58 (50 km2; 19 sq mi)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2014 estimate | 7,234,800[7] (100th) |

• Density | 6,544[5]/km2 (16,948.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $412.300 billion[8] (44th) |

• Per capita | $56,428[8] (10th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $310.074 billion[8] (36th) |

• Per capita | $42,437[8] (18th) |

| Gini (2011) | 53.7[9] high inequality |

| HDI (2014) | very high (12th) |

| Currency | Hong Kong dollar (HK$) (HKD) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+8 (not observed) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy yyyy年mm月dd日 |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +852 |

| ISO 3166 code | HK |

| Internet TLD | .hk .香港 |

| |

| Hong Kong | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 香港 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Fragrant Harbour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 香港特別行政區 (香港特區) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 香港特别行政区 (香港特区) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Template:Contains Chinese text

Hong Kong (Chinese: 香港; lit. 'Fragrant Harbour'), officially Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China, is an autonomous territory on the southern coast of China at the Pearl River Estuary and the South China Sea.[12] Hong Kong is known for its skyline and deep natural harbour.[13] It has a land area of 1104 km2 and shares its northern border with Guangdong Province of Mainland China. With around 7.2 million inhabitants of various nationalities,[note 1] Hong Kong is one of the world's most densely populated metropolises.

After the First Opium War (1839–42), Hong Kong became a British colony with the perpetual cession of Hong Kong Island, followed by Kowloon Peninsula in 1860 and a 99-year lease of the New Territories from 1898. Hong Kong remained under continuous British control for about a century until the Second World War, when Japan occupied the colony from December 1941 to August 1945. British control resumed in 1945 following the Surrender of Japan. In the 1980s, negotiations between the United Kingdom and China resulted in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, which provided for the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong on 30 June 1997. The territory became a special administrative region of China with a high degree of autonomy[14] on 1 July 1997 under the principle of one country, two systems.[15][16] Disputes over the perceived misapplication of this principle have contributed to popular protests, including the 2014 Umbrella Revolution.

In the late 1970s, Hong Kong became a major entrepôt in Asia-Pacific. The territory has developed into a major global trade hub and financial centre.[17] The 44th-largest economy in the world,[18] Hong Kong ranks top 10 in GDP (PPP) per capita, but also has the most severe income inequality among advanced economies. Hong Kong is one of the three most important financial centres alongside New York and London,[19] and the world's number one tourist destination city.[20] The territory has been named the freest market economy.[21] The service economy, characterised by free trade and low taxation, has been regarded as one of the world's most laissez-faire economic policies, and the currency, the Hong Kong dollar, is the 13th most traded currency in the world.[22]

The Hong Kong Basic Law is its quasi-constitution which empowers the region to develop relations and make agreements directly with foreign states and regions, as well as international organizations, in a broad range of appropriate fields.[23] It is an independent member of APEC, the IMF, WTO, FIFA and International Olympic Committee among others.

Limited land created a dense infrastructure and the territory became a centre of modern architecture, and has a larger number of highrises than any other city in the world.[24][25] Hong Kong has a highly developed public transportation network covering 90 per cent of the population, the highest in the world, and relies on mass transit by road or rail.[26][27] Air pollution remains a serious problem.[28][29] Loose emissions standards have resulted in a high level of atmospheric particulates.[30] Nevertheless, residents of Hong Kong (sometimes referred to as Hongkongers) enjoy one of the longest life expectancies in the world.[31][32]

Etymology

It is not known who was responsible for the Romanisation of the name "Hong Kong" but it is generally believed to be an early imprecise phonetic rendering of the pronunciation of the spoken Cantonese or Hakka name 香港, meaning "Fragrant Harbour".[33] Before 1842, the name referred to a small inlet—now Aberdeen Harbour (香港仔, Sidney Lau: heung1gong2 jai2, Jyutping: [hoeng1gong2 zai2] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: zh-latin (help), or Hiong1gong3 zai3 in a form of Hakka, literally means "Little Hong Kong")—between Aberdeen Island and the south side of Hong Kong Island, which was one of the first points of contact between British sailors and local fishermen.[34] As those early contacts are likely to have been with Hong Kong's early inhabitants, the Tankas (水上人), it is equally probable that the early Romanisation was a faithful execution of their speech, i.e. hong1, not heung1.[35] Detailed and accurate Romanisation systems for Cantonese were available and in use at the time.[36]

The reference to fragrance may refer to the sweet taste of the harbour's fresh water estuarine influx of the Pearl River, or to the incense from factories, lining the coast to the north of Kowloon, which was stored near Aberdeen Harbour for export before the development of the Victoria Harbour.[33]

In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking was signed and the name, Hong Kong, was first recorded on official documents to encompass the entirety of the island.[37]

The name had often been written as the single word Hongkong until the government adopted the current form in 1926.[38] Nevertheless, a number of century-old institutions still retain the single-word form, such as the Hongkong Post, Hongkong Electric and the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation.

The full official name, after 1997, is "Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China". This is the official title as mentioned in the Hong Kong Basic Law and the Hong Kong Government's website;[39] however, "Hong Kong Special Administrative Region" and "Hong Kong" are widely accepted.

Hong Kong has carried many nicknames: the most famous among those is the "Pearl of the Orient", which reflected the impressive night-view of the city's light decorations on the skyscrapers along both sides of the Victoria Harbour. The territory is also known as "Asia's World City".

History

Pre-colonial

Archaeological studies support human presence in the Chek Lap Kok area (now Hong Kong International Airport) from 35,000 to 39,000 years ago and on Sai Kung Peninsula from 6,000 years ago.[40][41][42]

Wong Tei Tung and Three Fathoms Cove are the earliest sites of human habitation in Hong Kong during the Paleolithic Period. It is believed that the Three Fathom Cove was a river-valley settlement and Wong Tei Tung was a lithic manufacturing site. Excavated Neolithic artefacts suggested cultural differences from the Longshan culture of northern China and settlement by the Che people, prior to the migration of the Baiyue (Viets) to Hong Kong.[43][44] Eight petroglyphs, which dated to the Shang dynasty in China, were discovered on the surrounding islands.[45]

Ancient China

In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, conquered the Baiyue tribes in Jiaozhi (modern Liangguang region and Vietnam) and incorporated the territory into imperial China for the first time. Modern Hong Kong was assigned to the Nanhai commandery (modern Nanhai District), near the commandery's capital city Panyu.[46][47][48] In Qin dynasty, the territory was ruled by Panyu County(番禺縣) up till Jin Dynasty.

The area of Hong Kong was consolidated under the kingdom of Nanyue (Southern Viet), founded by general Zhao Tuo in 204 BC after the collapse of the short-lived Qin dynasty.[49] When the kingdom of Nanyue was conquered by the Han Dynasty in 111 BC, Hong Kong was assigned to the Jiaozhi commandery. Archaeological evidence indicates that the population increased and early salt production flourished in this time period. Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb on the Kowloon Peninsula is believed to have been built during the Han dynasty.[50]

Imperial China

From the Jin dynasty to the early period of Tang dynasty, the territory that now comprises Hong Kong was governed by Bao'an County (寶安縣). In the Tang dynasty, the Guangdong region flourished as an international trading center. The Tuen Mun region in what is now Hong Kong's New Territories served as a port, naval base, salt production centre and, later, as base for the exploitation of pearls. Lantau Island was also a salt production centre, where the salt smugglers riots broke out against the government.

Under the Tang dynasty, the Guangdong (Canton) region flourished as a regional trading centre. In 736 AD, the first Emperor of Tang established a military stronghold in Tuen Mun in western Hong Kong to defend the coastal area of the region.[51] The first village school, Li Ying College, was established around 1075 AD in the modern-day New Territories under the Northern Song dynasty.[52] After their defeat by the Mongols, the Southern Song court briefly moved to modern-day Kowloon City (the Sung Wong Toi site), before its final defeat at the Battle of Yamen.[53]

From the mid-Tang dynasty to early Ming dynasty, the territory that now comprises Hong Kong was governed by Dongguan County (東莞縣/ 東官縣). In Ming dynasty, the area was governed by Xin'an County (新安縣) before it was colonized by the British government. The indigenous inhabitants of what is now Hong Kong are identified with several ethnicities, including Punti, Hakka, Tanka) and Hoklo.

The earliest European visitor on record was Jorge Álvares, a Portuguese explorer who arrived in 1513.[54][55] Having founded an establishment in Macau by 1557, Portuguese merchants began trading in southern China. However, subsequent military clashes between China and Portugal led to the expulsion of all Portuguese merchants from the rest of China.

In the mid-16th century, the Haijin order (closed-door, isolation policy) was enforced and it strictly forbade all maritime activities in order to prevent contact from foreigners by sea.[53] From 1661 to 1669, Hong Kong was directly affected by the Great Clearance of the Kangxi Emperor, who required the evacuation of coastal areas of Guangdong. About 16,000 people from Hong Kong and Bao'an County were forced to emigrate inland; 1,648 of those who evacuated were said to have returned after the evacuation was rescinded in 1669.[56][57]

British Crown Colony: 1842–1941

In 1839, the refusal of Qing authorities to support opium imports caused the outbreak of the First Opium War between the British Empire and the Qing Empire. Qing's defeat resulted in the occupation of Hong Kong Island by British forces on 20 January 1841. It was initially ceded under the Convention of Chuenpee, as part of a ceasefire agreement between Captain Charles Elliot and Governor Qishan. While a dispute between high-ranking officials of both countries led to the failure of the treaty's ratification, on 29 August 1842, Hong Kong Island was formally ceded in perpetuity to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland under the Treaty of Nanking.[58] The British officially established a Crown colony and founded the City of Victoria in the following year.[59]

The population of Hong Kong Island was 7,450 when the Union Flag raised over Possession Point on 26 January 1841. It mostly consisted of Tanka fishermen and Hakka charcoal burners, whose settlements scattered along several coastal hamlets. In the 1850s, a large number of Chinese immigrants crossed the then-free border to escape from the Taiping Rebellion. Other natural disasters, such as flooding, typhoons and famine in mainland China would play a role in establishing Hong Kong as a place for safe shelter.[60][61]

Further conflicts over the opium trade between Britain and Qing quickly escalated into the Second Opium War. Following the Anglo-French victory, the Crown Colony was expanded to include Kowloon Peninsula (south of Boundary Street) and Stonecutter's Island, both of which were ceded to the British in perpetuity under the Convention of Beijing in 1860.

In 1898, Britain obtained a 99-year lease from Qing under the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory, in which Hong Kong obtained a 99-year lease of the Lantau Island, the area north of Boundary Street in Kowloon up to Shenzhen River and over 200 other outlying islands.[62][63][64]

Hong Kong soon became a major entrepôt thanks to its free port status, attracting new immigrants to settle from both China and Europe alike. The society, however, remained racially segregated and polarised under British colonial policies. Despite the rise of a British-educated Chinese upper-class by the late-19th century, race laws such as the Peak Reservation Ordinance prevented ethnic Chinese in Hong Kong from acquiring houses in reserved areas, such as the Victoria Peak. At this time, the majority of the Chinese population in Hong Kong had no political representation in the British colonial government. There were, however, a small number of Chinese elites whom the British governors relied on, such as Sir Kai Ho and Robert Hotung, who served as communicators and mediators between the government and local population.

Hong Kong continued to experience modest growth during the first half of the 20th century. The University of Hong Kong was established in 1911 as the territory's oldest higher education institute. While there was an exodus of 60,000 residents for fear of a German attack on the British colony during the First World War, Hong Kong remained peaceful. Its population increased from 530,000 in 1916 to 725,000 in 1925 and reached 1.6 million by 1941.[65]

In 1925, Cecil Clementi became the 17th Governor of Hong Kong. Fluent in Cantonese and without a need for translator, Clementi introduced the first ethnic Chinese, Shouson Chow, into the Executive Council as an unofficial member. Under his tenure, Kai Tak Airport entered operation as RAF Kai Tak and several aviation clubs. In 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out when the Japanese Empire expanded its territories from northeastern China into the mainland proper. To safeguard Hong Kong as a freeport, Governor Geoffry Northcote declared the Crown Colony as a neutral zone.

Japanese occupation: 1941–45

As part of its military campaign in Southeast Asia during Second World War, the Japanese army moved south from Guangzhou of mainland China and attacked Hong Kong on 8 December 1941.[67] The Battle of Hong Kong ended with the British and Canadian defenders surrendering control of Hong Kong to Japan on 25 December 1941 in what was regarded by locals as Black Christmas.[68]

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, the Japanese army committed atrocities against civilians and POWs, such as the St. Stephen's College massacre. Local residents also suffered widespread food shortages, limited rationing and hyper-inflation arising from the forced exchange of currency from Hong Kong Dollars to Japanese military banknotes. The initial ratio of 2:1 was gradually devalued to 4:1 and ownership of Hong Kong Dollars was declared illegal and punishable by harsh torture. Due to starvation and forced deportation for slave labour to mainland China, the population of Hong Kong had dwindled from 1.6 million in 1941 to 600,000 in 1945, when Britain resumed control of the colony on 30 August 1945.[69]

Resumption of British rule and industrialisation: 1945–97

Hong Kong's population recovered quickly after the war, as a wave of skilled migrants from China flooded in for refuge from the Chinese Civil War. When the Communists gained control of mainland China in 1949, even more skilled migrants fled across the open border for fear of persecution.[62] Many newcomers, especially those who had been based in the major port cities of Shanghai and Guangzhou, established corporations and small- to medium-sized businesses and shifted their base operations to British Hong Kong.[62] The Chinese Communist Party's establishment of a socialist state in China on 1 October 1949 caused the British colonial government to reconsider Hong Kong's open border to mainland China. In 1951, a boundary zone was demarked as a buffer zone against potential military attacks from communist China. Border posts in the north of Hong Kong began operation in 1953 to regulate the movement of people and goods into and out of British Hong Kong.

In the 1950s, Hong Kong became the first of the Four Asian Tiger economies under rapid industrialisation driven by textile exports, manufacturing industries and re-exports of goods to China. As the population grew, with labour costs remaining low, living standards began to rise steadily.[70] The construction of the Shek Kip Mei Estate in 1953 marked the beginning of the public housing estate programme to provide shelter for the less privileged and to cope with the influx of immigrants.

Under Sir Murray MacLehose, 25th Governor of Hong Kong (1971–82), a series of reforms improved the public services, environment, housing, welfare, education and infrastructure of Hong Kong. MacLehose was British Hong Kong's longest-serving governor and, by the end of his tenure, had become one of the most popular and well-known figures in the Crown Colony. MacLehose laid the foundation for Hong Kong to establish itself as a key global city in the 1980s and early 1990s.

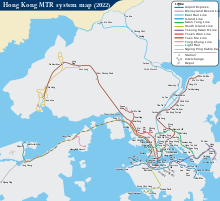

To resolve traffic congestion and to provide a more reliable means of crossing the Victoria Harbour, a rapid transit railway system (metro), the MTR, was planned from the 1970s onwards. The Island Line (Hong Kong Island), Kwun Tong Line (Kowloon Peninsula and East Kowloon) and Tsuen Wan Line (Kowloon and urban New Territories) opened in the early 1980s.[71]

Hong Kong's competitiveness in manufacturing gradually declined due to rising labour and property costs, as well as new development in southern China under the Open Door Policy introduced in 1978 which opened up China to foreign business. Nevertheless, towards the early 1990s, Hong Kong had established itself as a global financial centre along with London and New York, a regional hub for logistics and freight, one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia and the world's exemplar of Laissez-faire market policy.[72]

The Hong Kong question

Facing the uncertain future of Hong Kong, Governor MacLehose raised the question in the late 1970s. In 1983, the United Kingdom reclassifed Hong Kong as a British Dependent Territory (now British Overseas Territory) when reorganising global territories of the British Empire. Talks and negotiations began with China and concluded with the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration. Both countries agreed to transfer Hong Kong's sovereignty to the China on 1 July 1997, when Hong Kong would remain autonomous as a Special Administrative Region and be able to retain its free-market economy, British common law through the Hong Kong Basic Law, independent representation in international organisations (e.g. WTO and WHO), treaty arrangements and policy-making except foreign diplomacy and military defence.[62] It stipulated that Hong Kong would retain its laws and be guaranteed a high degree of autonomy for at least 50 years after the transfer. The Hong Kong Basic Law, based on English law, would serve as the constitutional document after the transfer. It was ratified in 1990.[62] Nevertheless, the expiry of the 1898 lease on the New Territories in 1997 created problems for business contracts, property leases and confidence among foreign investors.

Handover and Special Administrative Region status

Transfer of sovereignty

On 1 July 1997, the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China took place, officially marking the end of Hong Kong's 156 years under British colonial governance. As what was by far the largest remaining colony of the United Kingdom, the loss of Hong Kong also effectively represented the end of the British Empire. At the same time, Hong Kong switched its country of administration overnight to become China's first Special Administrative Region. Tung Chee-Hwa, a pro-Beijing business tycoon, was elected Hong Kong's first Chief Executive by a selected electorate of 800 in a televised ceremony.

Transition to Chinese rule

Soon after Hong Kong's reversion to China, the city suffered an economic double-blow from the Asian financial crisis and the pandemic of H5N1 bird flu; in December 1997, officials had to destroy 1.4 million chickens and ducks to contain the virus from spreading.[62] Subsequently, mismanagement of Tung's housing policy disrupted the market supply, sent properties prices in Hong Kong tumbling and caused many homeowners to become bankrupt due to negative equity. In 2003, Hong Kong was gravely affected by the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).[73][74] The World Health Organization reported 1,755 infected and 299 deaths in Hong Kong.[75] An estimated 380 million Hong Kong dollars (US$48.9 million) in contracts were lost as a result of the epidemic.[76]

Distrust of the Communist Party of China remained strong in the initial years of Chinese rule. A legacy of the democratic reforms by Chris Patten, China refused to recognise the legitimacy of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong after its 1994 direct election. The "Provisional" Legislative Council of Hong Kong (1997–99), which was unable to draft any new bills or authorise new legislation, completed its five-year term in 1999. The Legislative Council of Hong Kong (LegCo) resumed its full function after the 1999 LegCo election.

Despite the unopposed re-election of Tung in July 2002, the government's attempt to complete legislation of the Basic Law's Article 23 (National Security) aroused strong suspicion among Hong Kong citizens. This was due to the Article granting the police force right of access to private property, under the reason of 'safeguarding national security', without court warrants. Coupled with years of economic hardships and deflation following the Asian Financial Crisis, a mass demonstration broke out on 1 July 2003. This hastened the resignations of two government ministers and, eventually, that of Tung on 10 March 2005.[77]

Sir Donald Tsang, the then-Chief Secretary for Administration and ex-official of the British Hong Kong government, entered the 2005 election uncontested and was appointed by Beijing as the second Chief Executive of Hong Kong on 21 June 2005. Tsang also won a second term in office following the 2007 Chief Executive election under managed voting.[78] In 2009, Hong Kong hosted the 5th East Asian Games, in which nine national teams competed. The Games were the first and largest international multi-sport event ever organised and hosted by the city.[79] Major infrastructure and tourist projects also began under Sir Tsang's second term, including Hong Kong Disneyland, Ngong Ping 360 (for Tian Tan Buddha and Tseung Kwan O Line (new metro line) had their inaugurations and a new cultural complex, the West Kowloon Cultural District.

Tensions with mainland China

Since Hong Kong's reunification with China, there has been increasing social tension between Hong Kong residents and mainland Chinese due to cultural and linguistic differences, as well as accusations of unruly behaviour and spending habits of mainland Chinese visitors to the territory.[80] A 2011 survey (with a sample base of 541) in Hong Kong shows that 17% respondents considered themselves as "Chinese citizens", while 38% considered themselves just "Hong Kong citizens".[81]

In 2012 Chief Executive elections saw the Beijing backed candidate Leung Chun-Ying elected with 689 votes from a committee panel of 1,200 selected representatives, and assumed office on 1 July 2012.

Social conflicts also influenced the mass protests in 2014, primarily caused by the Chinese government's proposal on electoral reform. The debates over China's vision of granting Hong Kong full democracy have escalated into diplomatic rows between China and the United Kingdom.[82]

Governance

Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of autonomy, as its political and judicial systems operate independently from those of mainland China. In accordance with the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and the underlying principle of one country, two systems, Hong Kong has a "high degree of autonomy as a special administrative region in all areas except defence and foreign affairs".[note 2] The declaration stipulates that the region maintain its capitalist economic system and guarantees the rights and freedoms of its people for at least 50 years after the 1997 handover.[note 3] The guarantees over the territory's autonomy and the individual rights and freedoms are enshrined in the Hong Kong Basic Law, the territory's constitutional document, which outlines the system of governance of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, but which is subject to the interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC).[83][84]

The primary pillars of government are the Executive Council, the civil service, the Legislative Council, and the Judiciary. The Executive Council is headed by the Chief Executive who is elected by the Election Committee and then appointed by the Central People's Government.[85][86] The civil service is a politically neutral body that implements policies and provides government services, where public servants are appointed based on meritocracy.[87][88] The Legislative Council has 70 members, 40 seats are directly elected by universal suffrage by permanent residents of Hong Kong according to five geographical constituencies and a District Council functional constituency. 30 seats from functional constituencies are directly elected by a smaller electorate, which consists of corporate bodies and persons from various stipulated functional sectors. The entire council is headed by the President of the Legislative Council who serves as the speaker.[89][90] Judges are appointed by the Chief Executive on the recommendation of an independent commission.[15][91]

The implementation of the Basic Law, including how and when the universal suffrage promised therein is to be achieved, has been a major issue of political debate since the transfer of sovereignty. In 2002, the government's proposed anti-subversion bill pursuant to Article 23 of the Basic Law, which required the enactment of laws prohibiting acts of treason and subversion against the Chinese government, was met with fierce opposition, and eventually shelved.[92][93][94] Debate between pro-Beijing groups, which tend to support the Executive branch, and the Pan-democracy camp characterises Hong Kong's political scene, with the latter supporting a faster pace of democratisation, and the principle of one man, one vote.[95]

In 2004 the government failed to gain pan-democrat support to pass its so-called "district council model" for political reform.[96] In 2009, the government reissued the proposals as the "Consultation Document on the Methods for Selecting the Chief Executive and for Forming the LegCo in 2012". The document proposed the enlargement of the Election Committee, Hong Kong's electoral college, from 800 members to 1,200 in 2012 and expansion of the legislature from 60 to 70 seats. The ten new legislative seats would consist of five geographical constituency seats and five functional constituency seats, to be voted in by elected district council members from among themselves.[97] The proposals were destined for rejection by pan-democrats once again, but a significant breakthrough occurred after the Central Government in Beijing accepted a counter-proposal by the Democratic Party. In particular, the Pan-democracy camp was split when the proposal to directly elect five newly created functional seats was not acceptable to two constituent parties. The Democratic Party sided with the government for the first time since the handover and passed the proposals with a vote of 46–12.[98]

On 31 August 2014, China disapproved a full democracy in Hong Kong by ruling that three candidates could run for elections as leader in 2017, and they would be chosen by a nomination committee.[99]

Legal system and judiciary

Hong Kong's legal system is completely independent from the legal system of mainland China. In contrast to mainland China's civil law system, Hong Kong continues to follow the English common law tradition established under British rule.[100] The essence of English common law is that it is made by judges sitting in courts, applying legal precedent (stare decisis) to the facts before them. For example, murder is a common law crime rather than one established by an Act of Parliament. Common law can be amended or repealed by Parliament; murder, for example, now carries a mandatory life sentence rather than the death penalty. According to Article 92 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong's courts may refer to decisions rendered by courts of other common law jurisdictions as precedents,[15][101] and judges from other common law jurisdictions, most commonly England, Canada and Australia, are allowed to sit as non-permanent judges of the Court of Final Appeal.[15][101]

Structurally, the court system consists of the Court of Final Appeal, the High Court, which is made up of the Court of Appeal and the Court of First Instance, and the District Court, which includes the Family Court.[102] Other adjudicative bodies include the Lands Tribunal, the Magistrates' Courts, the Juvenile Court, the Coroner's Court, the Labour Tribunal, the Small Claims Tribunal, and the Obscene Articles Tribunal.[102] Justices of the Court of Final Appeal are appointed by Hong Kong's Chief Executive.[15][101] The Court of Final Appeal has the power of final adjudication with respect to the law of Hong Kong as well as the power of final interpretation over local laws including the power to strike down local ordinances on the grounds of inconsistency with the Basic Law.[103][104]

The Department of Justice is responsible for handling legal matters for the government. Its responsibilities include providing legal advice, criminal prosecution, civil representation, legal and policy drafting and reform, and international legal co-operation between different jurisdictions.[100] Apart from prosecuting criminal cases, lawyers of the Department of Justice act on behalf of the government in all civil and administrative lawsuits against the government.[100] As protector of the public interest, the department may apply for judicial reviews and may intervene in any cases involving the greater public interest.[105] The Basic Law protects the Department of Justice from any interference by the government when exercising its control over criminal prosecution.[106][107]

Foreign relations

Hong Kong continues to play an active role in the international arena and maintains close contact with its international partners. Under the Basic Law, Hong Kong is exclusively in charge of its external relations, whilst the Government of the China is responsible for its foreign affairs. According to the Basic Law, Hong Kong may on its own, using the name "Hong Kong, China", maintain and develop relations and conclude and implement agreements with foreign states and regions and relevant international organisations in the appropriate fields, including the economic, trade, financial and monetary, shipping, communications, tourism, cultural and sports fields.[108]

As a separate customs territory, Hong Kong maintains and develops relations with foreign states and regions, and plays an active role in such international organisations as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA), and the International Basketball Federation (FIBA) in its own right under the name of Hong Kong, China. Under such special conditions, Hong Kong's international partners usually exercise particular policies to maintain relations with Hong Kong, such as the United States-Hong Kong Policy Act.

There is a large foreign representation in Hong Kong, including 59 Consulates-General, 62 Consulates and 5 officially recognised international bodies, such as the Office of the European Union.[109] Due to Hong Kong's special status, some countries' Consulates-General operate independently of their Embassies in Beijing. For example, the US Consulate General to Hong Kong is not under the jurisdiction of the Embassy in Beijing, and reports directly to the US Department of State.[110] Similarly, the British Consulate-General reports directly to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, instead of the British Ambassador in Beijing.[111]

Human rights

The Hong Kong government generally respects the human rights of its citizens, and members of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong and the District Council of Hong Kong are elected into office by Hong Kong citizens. However, there are 27 ex officio members of the district council (the Rural Committee Chairmen in the New Territories) as of the fifth District Council Assembly, and roughly half of the legislative council seats are elected by 3% of the people in Hong Kong through the functional constituency. The imbalance of voting power in the LegCo has led to widespread criticism of the its inability to represent Hongkonger's socio-economic needs.[112] In addition, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong is elected by 1,200 members based on their contributions to four different sectors of Hong Kong's society. This policy has received criticism from various political figures in Hong Kong, and led to the Umbrella Revolution. Plans to expand the voting population had begun to appear in the 2000s, and political figures liaised with the government to provide universal suffrage.

There are restrictions on freedom of the press and freedom of assembly.[113][114] 200,000 migrant workers cannot make complaints against their employers since they face deportation if dismissed from their jobs. A 2008 law against racial discrimination does not cover mainlanders, immigrants or migrant workers.[115] The police have been accused of using heavy-handed tactics toward protesters in public rallies,[116] and there is controversy regarding the extensive powers of the police.[117] Covert surveillance is another major concern.[118]

Hong Kong has a higher age-of-consent and harsher punishments for illegal homosexual acts.[119]

Internet censorship in Hong Kong operates under different principles and regulations from those of mainland China.[120] In November 2015, the newly established Innovation and Technology Bureau pushed for the legislation of the Internet Article 23, which would severely limit the legality of derivative works[121] and other activities previously permitted on the Internet.[122][123] Supporters of the bill point to the fact that Hong Kong is lagging behind in the protection of intellectual property rights, but detractors state that creative work on the Internet should be exempt from legislation, and the ordinance would severely violate human rights.

Regions and Districts

Hong Kong consists of three regions: Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories. The regions are subdivided into 18 geographic districts, each represented by a district council which advises the government on local matters such as public facilities, community programmes, cultural activities, and environmental improvements.[124]

There are a total of 541 district council seats, 412 of which are elected; the rest are appointed by the Chief Executive and 27 ex officio chairmen of rural committees.[124] The Home Affairs Department communicates government policies and plans to the public through the district offices.[125] Hong Kong has a unitary system of government; no local government has existed since the two municipal councils were abolished in 2000. As such there is no formal definition for its cities and towns.

Military

When Hong Kong's sovereignty transferred to People's Republic of China on 1 July 1997, the British barracks were replaced by a garrison of the People's Liberation Army, comprising ground, naval, and air forces, who come under the command of the Chinese Central Military Commission.

The Basic Law of Hong Kong protects local civil affairs against any interference by the garrison; members of the garrison are subject to Hong Kong laws. The Hong Kong Government remains responsible for the maintenance of public order; however, it may ask the PRC government for assistance from the garrison in maintaining public order and in disaster relief. The PRC government is now responsible for the costs of maintaining the garrison.[92][126]

In January 2015, Hong Kong Army Cadets Association was formed for Hong Kong children over 6 years old. The inauguration ceremony was held at a PLA naval base in Hong Kong; only pro-Beijing press was invited into the venue.[127]

Geography and climate

Hong Kong is located on China's south coast, 60 km (37 mi) east of Macau on the opposite side of the Pearl River Delta. It is surrounded by the South China Sea on the east, south, and west, and borders the Guangdong city of Shenzhen to the north over the Shenzhen River. The territory's 1,104 km2 (426 sq mi) area consists of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, the New Territories, and over 200 offshore islands, of which the largest is Lantau Island. Of the total area, 1,054 km2 (407 sq mi) is land and 50 km2 (19 sq mi) is inland water. Hong Kong claims territorial waters to a distance of 3 nautical miles (5.6 km). Its land area makes Hong Kong the 179th largest inhabited territory in the world.[6][12]

As much of Hong Kong's terrain is hilly to mountainous with steep slopes, less than 25% of the territory's landmass is developed, and about 40% of the remaining land area is reserved as country parks and nature reserves.[128] Low altitude vegetation in Hong Kong is dominated by secondary rainforests, as the primary forest was mostly cleared during the Second World War, and higher altitudes are dominated by grasslands. Most of the territory's urban development exists on Kowloon peninsula, along the northern edge of Hong Kong Island, and in scattered settlements throughout the New Territories.[129] The highest elevation in the territory is at Tai Mo Shan, 957 metres (3,140 ft) above sea level.[130] Hong Kong's long and irregular coast provides it with many bays, rivers and beaches.[131] On 18 September 2011, UNESCO listed the Hong Kong National Geopark as part of its Global Geoparks Network. Hong Kong Geopark is made up of eight Geo-Areas distributed across the Sai Kung Volcanic Rock Region and Northeast New Territories Sedimentary Rock Region.[132]

Despite Hong Kong's reputation of being intensely urbanised, the territory has tried to promote a green environment,[133] and recent growing public concern has prompted the severe restriction of further land reclamation from Victoria Harbour.[134] Awareness of the environment is growing as Hong Kong suffers from increasing pollution compounded by its geography and tall buildings. Approximately 80% of the city's smog originates from other parts of the Pearl River Delta.[135]

Though it is situated just south of the Tropic of Cancer, Hong Kong has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa). Summer is hot and humid with occasional showers and thunderstorms, and warm air coming from the southwest. Typhoons most often occur in summer. They sometimes result in flooding or landslides. Winters are mild and usually start sunny, becoming cloudier towards February; the occasional cold front brings strong, cooling winds from the north. The most temperate seasons are spring, which can be changeable, and autumn, which is generally sunny and dry.[136] Snowfall is extremely rare, and usually occurs in areas of high elevation. Hong Kong averages 1,948 hours of sunshine per year,[137] while the highest and lowest ever recorded temperatures at the Hong Kong Observatory are 36.3 °C (97.3 °F) on 8 August 2015 and 0.0 °C (32.0 °F)* on 18 January 1893, respectively.[138][139] The highest and lowest ever recorded temperatures across all of Hong Kong, on the other hand, are 37.9 °C (100.2 °F)* at Happy Valley on 8 August 2015 and −6.0 °C (21.2 °F)* at Tai Mo Shan on 24 January 2016, respectively. With data beginning in 1998, the highest and lowest temperatures ever recorded at the Hong Kong International Airport are 37.7 °C (99.9 °F)* on 9 August 2015 and 2.9 °C (37.2 °F)* on 24 January 2016, respectively. Template:Hong Kong weatherboxTemplate:Hong Kong Airport weatherbox

Economy

As one of the world's leading international financial centres, Hong Kong has a major capitalist service economy characterised by low taxation and free trade. The currency, Hong Kong dollar, is the eighth most traded currency in the world as of 2010[update].[22] Hong Kong was once described by Milton Friedman as the world's greatest experiment in laissez-faire capitalism, but has since instituted a regime of regulations including a minimum wage.[140] It maintains a highly developed capitalist economy, ranked the freest in the world by the Index of Economic Freedom every year since 1995.[141][142][143] It is an important centre for international finance and trade, with one of the greatest concentrations of corporate headquarters in the Asia-Pacific region,[144] and is known as one of the Four Asian Tigers for its high growth rates and rapid development from the 1960s to the 1990s. Between 1961 and 1997 Hong Kong's gross domestic product grew 180 times while per-capita GDP increased 87 times over.[145][146][147]

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is the seventh largest in the world and has a market capitalisation of US$2.3 trillion as of December 2009.[148] In that year, Hong Kong raised 22 percent of worldwide initial public offering (IPO) capital, making it the largest centre of IPOs in the world [149] and the easiest place to raise capital. The Hong Kong dollar has been pegged to the US dollar since 1983.[150]

The Hong Kong Government has traditionally played a mostly passive role in the economy, with little by way of industrial policy and almost no import or export controls. Market forces and the private sector were allowed to determine practical development. Under the official policy of "positive non-interventionism", Hong Kong is often cited as an example of laissez-faire capitalism. Following the Second World War, Hong Kong industrialised rapidly as a manufacturing centre driven by exports, and then underwent a rapid transition to a service-based economy in the 1980s.[151] Since then, it has grown to become a leading centre for management, financial, IT, business consultation and professional services.

Hong Kong matured to become a financial centre in the 1990s, but was greatly affected by the Asian financial crisis in 1998, and again in 2003 by the SARS outbreak. A revival of external and domestic demand has led to a strong recovery, as cost decreases strengthened the competitiveness of Hong Kong exports and a long deflationary period ended.[152][153] Government intervention, initiated by the later colonial governments and continued since 1997, has steadily increased, with the introduction of export credit guarantees, a compulsory pension scheme, a minimum wage, anti-discrimination laws, and a state mortgage backer.[140]

The territory has little arable land and few natural resources, so it imports most of its food and raw materials. Imports account for more than 90% of Hong Kong's food supply, including nearly all of the meat and rice available there.[154] Agricultural activity—relatively unimportant to Hong Kong's economy and contributing just 0.1% of its GDP—primarily consists of growing premium food and flower varieties. Hong Kong is the world's eleventh largest trading entity,[155] with the total value of imports and exports exceeding its gross domestic product. It is the world's largest re-export centre.[156] Much of Hong Kong's exports consist of re-exports,[157] which are products made outside of the territory, especially in mainland China, and distributed via Hong Kong. Its physical location has allowed the city to establish a transportation and logistics infrastructure that includes the world's second busiest container port and the world's busiest airport for international cargo. Even before the transfer of sovereignty, Hong Kong had established extensive trade and investment ties with the mainland, which now enable it to serve as a point of entry for investment flowing into the mainland. At the end of 2007, there were 3.46 million people employed full-time, with the unemployment rate averaging 4.1% for the fourth straight year of decline.[158] Hong Kong's economy is dominated by the service sector, which accounts for over 90% of its GDP, while industry constitutes 9%. Inflation was at 2.5% in 2007.[159] Hong Kong's largest export markets are mainland China, the United States, and Japan.[6]

As of 2010[update] Hong Kong is the eighth most expensive city for expatriates, falling from fifth position in the previous year.[160] Hong Kong is ranked fourth in terms of the highest percentage of millionaire households, behind Switzerland, Qatar, and Singapore with 8.5 percent of all households owning at least one million US dollars.[161] Hong Kong is also ranked second in the world by the most billionaires per capita (one per 132,075 people), behind Monaco.[162] In 2011, Hong Kong was ranked second in the Ease of Doing Business Index, behind Singapore.[163]

Hong Kong is ranked No. 1 in the world in the Crony Capitalism Index by the Economist.[164]

In 2014, Hong Kong was the eleventh most popular destination for international tourists among countries and territories worldwide, with a total of 27.8 million visitors contributing a total of US$38,376 million in international tourism receipts. Hong Kong is also the most popular city for tourists, nearly two times of its nearest competitor Macau.[165]

Infrastructure

Hong Kong's transportation network is highly developed. Over 90% of daily travels (11 million) are on public transport,[26] the highest such percentage in the world.[27] Payment can be made using the Octopus card, a stored value system introduced by the MTR (Mass Transit Railway), which is widely accepted on railways, buses and ferries, and accepted like cash at other outlets.[166][167]

The city's main railway company (KCRC) was merged with MTR in 2007, creating a comprehensive rail network for the whole territory (also called MTR).[168] The MTR rapid transit system has 152 stations which serve 3.4 million people a day.[169] Hong Kong Tramways, which has served the territory since 1904, covers the northern parts of Hong Kong Island.[170]

Hong Kong's bus service is franchised and run by private operators. Five privately owned companies provide franchised bus service across the territory, together operating more than 700 routes as of 2014[update]. The largest are Kowloon Motor Bus, providing 402 routes in Kowloon and New Territories, and Citybus, operating 154 routes on Hong Kong Island; both run cross-harbour services. Double-decker buses were introduced to Hong Kong in 1949, and are now almost exclusively used; single-decker buses remain in use for routes with lower demand or roads with lower load capacity. Public light buses serve most parts of Hong Kong, particularly areas where standard bus lines cannot reach or do not reach as frequently, quickly, or directly.[171]

The Star Ferry service, founded in 1888, operates two lines across Victoria Harbour and provides scenic views of Hong Kong's skyline for its 53,000 daily passengers.[172] It acquired iconic status following its use as a setting on The World of Suzie Wong. Travel writer Ryan Levitt considered the main Tsim Sha Tsui to Central route one of the most picturesque in the world.[173] Other ferry services are provided by operators serving outlying islands, new towns, Macau, and cities in mainland China. Hong Kong is famous for its junks traversing the harbour, and small kai-to ferries that serve remote coastal settlements.[174][175] The Port of Hong Kong is a busy deepwater port, specialising in container shipping.[176]

Hong Kong Island's steep, hilly terrain was initially served by sedan chairs.[177] The Peak Tram, the first public transport system in Hong Kong, has provided vertical rail transport between Central and Victoria Peak since 1888.[178] In Central and Western district, there is an extensive system of escalators and moving pavements, including the longest outdoor covered escalator system in the world, the Mid-Levels escalator.[179]

Hong Kong International Airport is a leading air passenger gateway and logistics hub in Asia and one of the world's busiest airports in terms of international passenger and cargo movement, serving more than 47 million passengers and handling 3.74 million tonnes (4.12 million tons) of cargo in 2007.[180] It replaced the overcrowded Kai Tak Airport in Kowloon in 1998, and has been rated as the world's best airport in a number of surveys.[181] Over 85 airlines operate at the two-terminal airport and it is the primary hub of Cathay Pacific, Dragonair, Air Hong Kong, Hong Kong Airlines, and Hong Kong Express.[180][182]

Providing an adequate water supply for Hong Kong has always been difficult because the region has few natural lakes and rivers, inadequate groundwater sources (inaccessible in most cases due to the hard granite bedrock found in most areas in the territory), a high population density, and extreme seasonable variations in rainfall. Thus about 70 percent of water demand is met by importing water from the Dongjiang River in neighbouring Guangdong province. In addition, freshwater demand is curtailed by the use of seawater for toilet flushing, using a separate distribution system.[183]

Demographics

The territory's population in mid-2015 is 7.30 million,[184] with an average annual growth rate of 0.8% over the previous 5 years.[5][185] The current population of Hong Kong comprises 91% ethnic Chinese.[5][5][186][187] A major part of Hong Kong's Cantonese-speaking majority originated from the neighbouring Guangdong province,[188] from where many fled during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Civil War, and the communist rule in China.[189][190][191][192]

Residents of the Mainland do not automatically receive the Right of Abode, and many may not enter the territory freely. Like other non-natives, they may apply for the Right of Abode after seven years of continuous residency. Some of the rights may also be acquired by marriage (e.g., the right to work), but these do not include the right to vote or stand for office.[93] However, the influx of immigrants from mainland China, approximating 45,000 per year, is a significant contributor to its population growth – a daily quota of 150 Mainland Chinese with family ties in Hong Kong are granted a "one way permit".[193] Life expectancy in Hong Kong is 81.2 years for males and 86.9 years for females as of 2014[update], making it the highest life expectancy in the world.[6][194]

About 91% of the people of Hong Kong are of Chinese descent,[5][186][187] the majority of whom are Taishanese, Chiu Chow, other Cantonese people, and Hakka. Hong Kong's Han majority originate mainly from the Guangzhou and Taishan regions in Guangdong province.[188] The remaining 6.9% of the population is composed of non-ethnic Chinese.[5] There is a South Asian population of Indians, Pakistanis and Nepalese; some Vietnamese refugees have become permanent residents of Hong Kong. There are also Britons, Americans, Canadians, Japanese, and Koreans working in the city's commercial and financial sector.[note 4] In 2011, 133,377 foreign domestic helpers from Indonesia and 132,935 from the Philippines were working in Hong Kong.[198]

Hong Kong's de facto official language is Cantonese, a variety of Chinese originating from Guangdong province to the north of Hong Kong.[199] English is also an official language, and according to a 1996 by-census is spoken by 3.1 percent of the population as an everyday language and by 34.9 percent of the population as a second language.[200] Signs displaying both Chinese and English are common throughout the territory. Since the 1997 Handover, an increase in immigrants from mainland China and greater interaction with the mainland's economy have brought an increasing number of Mandarin speakers to Hong Kong.[201]

Religion

A majority of residents of Hong Kong have no religious affiliation, professing a form of agnosticism or atheism.[202] According to the US Department of State 43 percent of the population practices some form of religion.[203] Some figures put it higher, according to a Gallup poll, 64% of Hong Kong residents do not believe in any religion,[204][205] and possibly 80% of Hong Kong claim no religion.[206] In Hong Kong teaching evolution won out in curriculum dispute about whether to teach other explanations, and that creationism and intelligent design will form no part of the senior secondary biology curriculum.[207][208]

Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of religious freedom, guaranteed by the Basic Law. Hong Kong's main religions are Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism; a local religious scholar in contact with major denominations estimates there are approximately 1.5 million Buddhists and Taoists.[203] A Christian community of around 833,000 forms about 11.7% of the total population;[209] Protestants forms a larger number than Roman Catholics at a rate of 4:3, although smaller Christian communities exist, including the Latter-day Saints[210] and Jehovah's Witnesses.[211] The Anglican and Roman Catholic churches each freely appoint their own bishops, unlike in mainland China. There are also Sikh, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu and Bahá'í communities.[212] The practice of Falun Gong is tolerated.[213]

Personal income

Statistically Hong Kong's income gap is the greatest in Asia Pacific. According to a report by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme in 2008, Hong Kong's Gini coefficient, at 0.53, was the highest in Asia and "relatively high by international standards".[214][215] However, the government has stressed that income disparity does not equate to worsening of the poverty situation, and that the Gini coefficient is not strictly comparable between regions. The government has named economic restructuring, changes in household sizes, and the increase of high-income jobs as factors that have skewed the Gini coefficient.[216][217]

Education

Hong Kong's education system used to roughly follow the system in England,[218] although international systems exist. The government maintains a policy of "mother tongue instruction" (Chinese: 母語教學) in which the medium of instruction is Cantonese,[219] with written Chinese and English, while some of the schools are using English as the teaching language. In secondary schools, 'biliterate and trilingual' proficiency is emphasised, and Mandarin-language education has been increasing.[220] The Programme for International Student Assessment ranked Hong Kong's education system as the second best in the world.[221]

Hong Kong's public schools are operated by the Education Bureau. The system features a non-compulsory three-year kindergarten, followed by a compulsory six-year primary education, a compulsory three-year junior secondary education, a non-compulsory two-year senior secondary education leading to the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examinations and a two-year matriculation course leading to the Hong Kong Advanced Level Examinations.[222] The New Senior Secondary academic structure and curriculum was implemented in September 2009, which provides for all students to receive three years of compulsory junior and three years of compulsory senior secondary education.[223][224] Under the new curriculum, there is only one public examination, namely the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education.[225]

Most comprehensive schools in Hong Kong fall under three categories: the rarer public schools; the more common subsidised schools, including government aids-and-grant schools; and private schools, often run by Christian organisations and having admissions based on academic merit rather than on financial resources. Outside this system are the schools under the Direct Subsidy Scheme and private international schools.[224]

There are eight public and one private universities in Hong Kong, the oldest being the University of Hong Kong (HKU), established in 1910–1912.[226] The Chinese University of Hong Kong was founded in 1963 to fulfill the need for a university with a medium of instruction of Chinese.[227] Competition among students to receive an offer for an undergraduate programme is fierce as the annual number of intakes is limited, especially when some disciplines are offered by select tertiary institutions, like medicine which is provided by merely two medical schools in the territory, the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine at the University of Hong Kong and the Faculty of Medicine of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In addition to the public post-secondary institutions there are also a number of private higher institutions which offer higher diplomas and associate degree courses for those who fail to enter a college for a degree study so as to boost their qualification of education, some of whom can have a second chance of getting into a university if they have a good performance in these sub-degree courses.[228][229]

Health

There are 13 private hospitals and more than 40 public hospitals in Hong Kong.[230] There is little interaction between public and private healthcare.[231] The hospitals offer a wide range of healthcare services, and some of the territory's private hospitals are considered to be world class.[232] According to UN estimates, Hong Kong has one of the longest life expectancies of any country or territory in the world.[31] As of 2012[update], Hong Kong women are the longest living demographic group in the world.[32]

There are two medical schools in the territory, one based at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the other at the University of Hong Kong.[233][234] Both have links with public sector hospitals.[233][235] With respect to postgraduate education, traditionally many doctors in Hong Kong have looked overseas for further training, and many took British Royal College exams such as the MRCP(UK) and the MRCS(UK). However, Hong Kong has been developing its own postgraduate medical institutions, in particular the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, and this is gradually taking over the responsibility for all postgraduate medical training in the territory.

Since 2011, there have been growing concerns that mothers-to-be from mainland China, in a bid to obtain the right of abode in Hong Kong and the benefits that come with it, have saturated the neonatal wards of the city's hospitals both public and private. This has led to protest from local pregnant women for the government to remedy the issue, as they have found difficulty in securing a bed space for giving birth and routine check-ups. Other concerns in the decade of 2001–2010 relate to the workload medical staff experience; and medical errors and mishaps, which are frequently highlighted in local news.[236]

Culture

Hong Kong is frequently described as a place where "East meets West", reflecting the culture's mix of the territory's Chinese roots with influences from its time as a British colony.[237] Concepts like feng shui are taken very seriously, with expensive construction projects often hiring expert consultants, and are often believed to make or break a business.[238] Other objects like Ba gua mirrors are still regularly used to deflect evil spirits,[239] and buildings often lack any floor number that has a 4 in it,[240] due to its similarity to the word for "die" in Cantonese.[241] The fusion of east and west also characterises Hong Kong's cuisine, where dim sum, hot pot, and fast food restaurants coexist with haute cuisine.[242]

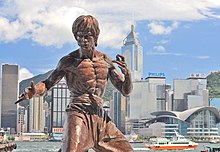

Hong Kong is a recognised global centre of trade and calls itself an "entertainment hub".[243] Its martial arts film genre gained a high level of popularity in the late 1960s and 1970s. Several Hollywood performers, notable actors and martial artists have originated from Hong Kong cinema, notably Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Chow Yun-fat, Michelle Yeoh, Maggie Cheung and Jet Li. A number of Hong Kong film-makers have achieved widespread fame in Hollywood, such as John Woo, Wong Kar-wai, and Stephen Chow.[243] Homegrown films such as Chungking Express, Infernal Affairs, Shaolin Soccer, Rumble in the Bronx, In the Mood for Love and Echoes of the Rainbow have gained international recognition. Hong Kong is the centre for Cantopop music, which draws its influence from other forms of Chinese music and Western genres, and has a multinational fanbase.[244]

The Hong Kong government supports cultural institutions such as the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. The government's Leisure and Cultural Services Department subsidises and sponsors international performers brought to Hong Kong. Many international cultural activities are organised by the government, consulates, and privately.[245][246]

Hong Kong has two licensed terrestrial broadcasters – ATV and TVB. There are three local and a number of foreign suppliers of cable and satellite services.[247] The production of Hong Kong's soap dramas, comedy series, and variety shows reach audiences throughout the Chinese-speaking world. Magazine and newspaper publishers in Hong Kong distribute and print in both Chinese and English, with a focus on sensationalism and celebrity gossip.[248] The media in Hong Kong is relatively free from official interference compared to Mainland China, although the Far Eastern Economic Review points to signs of self-censorship by media whose owners have close ties to or business interests in the People's Republic of China and states that even Western media outlets are not immune to growing Chinese economic power.[249]

Hong Kong offers wide recreational and competitive sport opportunities despite its limited land area. It sends delegates to international competitions such as the Olympic Games and Asian Games, and played host to the equestrian events during the 2008 Summer Olympics.[250] There are major multipurpose venues like Hong Kong Coliseum and MacPherson Stadium. Hong Kong's steep terrain and extensive trail network with expansive views attracts hikers, and its rugged coastline provides many beaches for swimming.[251]

Sport

Sports in Hong Kong are a significant part of its culture. Due mainly to British influence going as far back as the late 19th century, Hong Kong had an earlier introduction to Western athletics compared to other Asia regions. Football, basketball, swimming, badminton, table tennis, cycling and running have the most participants and spectators. In 2009, Hong Kong successfully organised the V East Asian Games. Other major international sporting events including the Equestrian at the 2008 Summer Olympics, Hong Kong Sevens, Hong Kong Marathon, AFC Asian Cup, EAFF East Asian Cup, Hong Kong Tennis Classic, Premier League Asia Trophy, and Lunar New Year Cup are also held in the territory. As of 2010[update], there were 32 Hong Kong athletes from seven sports ranking in world's Top 20, 29 athletes in six sports in Asia top 10 ranking. Moreover, Hong Kong athletes with disabilities are equally impressive in their performance as of 2009[update], having won four world championships and two Asian Championships.[252]

Architecture

According to Emporis, there are 1,223 skyscrapers in Hong Kong, which puts the city at the top of world rankings.[253] It has more buildings taller than 500 feet (150 m) than any other city. The high density and tall skyline of Hong Kong's urban area is due to a lack of available sprawl space, with the average distance from the harbour front to the steep hills of Hong Kong Island at 1.3 km (0.81 mi),[254] much of it reclaimed land. This lack of space causes demand for dense, high-rise offices and housing. Thirty-six of the world's 100 tallest residential buildings are in Hong Kong.[255] More people in Hong Kong live or work above the 14th floor than anywhere else on Earth, making it the world's most vertical city.[24][25]

As a result of the lack of space and demand for construction, few older buildings remain, and the city is becoming a centre for modern architecture. The International Commerce Centre (ICC), at 484 m (1,588 ft) high, is the tallest building in Hong Kong and the third tallest in the world, by height to roof measurement.[256] The tallest building prior to the ICC is Two International Finance Centre, at 415 m (1,362 ft) high.[257] Other recognisable skyline features include the HSBC Headquarters Building, the triangular-topped Central Plaza with its pyramid-shaped spire, The Center with its night-time multi-coloured neon light show; A Symphony of Lights and I. M. Pei's Bank of China Tower with its sharp, angular façade. According to the Emporis website, the city skyline has the biggest visual impact of all world cities.[258] Also, Hong Kong's skyline is often regarded to be the best in the world,[259] with the surrounding mountains and Victoria Harbour complementing the skyscrapers.[260][261] Most of the oldest remaining historic structures, including the Tsim Sha Tsui Clock Tower, the Central Police Station, and the remains of Kowloon Walled City were constructed during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[262][263][264]

There are many development plans in place, including the construction of new government buildings,[265] waterfront redevelopment in Central,[266] and a series of projects in West Kowloon.[267] More high-rise development is set to take place on the other side of Victoria Harbour in Kowloon, as the 1998 closure of the nearby Kai Tak Airport lifted strict height restrictions.[268] The Urban Renewal Authority is highly active in demolishing older areas, including the razing and redevelopment of Kwun Tong town centre, an approach which has been criticised for its impact on the cultural identity of the city and on lower-income residents.

Cityscape

See also

Notes

- ^ The identity of Hong Kong Permanent Resident can be of any nationality, Chinese, British, or others. A person not of Chinese nationality who has entered Hong Kong with a valid travel document, has ordinarily resided in Hong Kong for a continuous period of not less than 7 years and has taken Hong Kong as his or her place of permanent residence are legally recognized as a Hongkonger. See "Right of Abode" of The Immigration Department of Hong Kong

- ^ Section 3(2) of the Sino-British Joint Declaration states in part: "The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region will enjoy a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs which, are the responsibilities of the Central People's Government."

- ^ Section 3(5) of the Sino-British Joint Declaration states that the social and economic systems and lifestyle in Hong Kong will remain unchanged, and mentions rights and freedoms ensured by law. Section 3(12) states in part: "The above-stated basic policies of the People's Republic of China ... will remain unchanged for 50 years."

- ^ The results of the 2011 census showed that the "white" population had increased from 36,384 in 2006 to 54,740 an increase of 50.4 percent.[195][196][197]

References

Citations

- ^ Basic Law – Anthem

- ^ "Should there be any discrepancy between the English and Chinese versions of this notice, the ENGLISH VERSION SHALL PREVAIL". The Legislative Council Commission. 12 December 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Note: Cantonese is the de facto standard of Chinese used - ^ Section 3(1) of the Official Languages Ordinance (Cap 5) provides that the "English and Chinese languages are declared to be the official languages of Hong Kong." The Ordinance does not explicitly specify the standard for "Chinese". While Mandarin and Simplified Chinese characters are used as the spoken and written standards in mainland China, Cantonese and Traditional Chinese characters are the long-established de facto standards in Hong Kong.

- ^ "Disclaimer and Copyright Notice". The Legislative Council Commission. 12 December 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g 2011 Population Census – Summary Results (PDF) (Report). Census and Statistics Department. February 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Hong Kong". The World Factbook. CIA. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Mid-year Population for 2014". Census and Statistics Department (Hong Kong). 12 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Hong Kong". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Half-yearly Economic Report 2012" (PDF). Government of Hong Kong. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "2015 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Ecological Footprint Atlas 2010" (PDF). Global Footprint Network. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Geography and Climate, Hong Kong" (PDF). Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ Ash, Russell (2006). The Top 10 of Everything 2007. Hamlyn. p. 78. ISBN 0-600-61532-4.

- ^ "Basic Law Bulletin Issue No. 2" (PDF). Department of Justice, HKSAR.

- ^ a b c d e "Basic Law, Chapter IV, Section 4". Basic Law Promotion Steering Committee. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Russell, Peter H.; O'Brien, David M. (2001). Judicial Independence in the Age of Democracy: Critical Perspectives from around the World. University of Virginia Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-8139-2016-0.

- ^ "2014 Global Cities Index and Emerging Cities Outlook" (PDF). Retrieved April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Field listing – GDP (PPP exchange rate), CIA World Factbook

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 16" (PDF). Long Finance. September 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Top 100 City Destinations, Ranking". Euromonitor International. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ "Hong Kong Economy: Population, Facts, GDP, Business, Trade, Inflation". www.heritage.org. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Triennial Central Bank Survey: Report on global foreign exchange market activity in 2010" (PDF). Monetary and Economic Department. Bank for International Settlements: 12. December 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Article 151, Chapter 7, Hong Kong Basic Law

- ^ a b "Vertical Cities: Hong Kong/New York". Time Out. 3 August 2008. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Home page". Skyscraper Museum. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Public Transport Introduction". Transport Department, Hong Kong Government. Archived from the original on 7 July 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ a b Lam, William H. K.; Bell, Michael G. H. (2003). Advanced Modeling for Transit Operations and Service Planning. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-08-044206-8.

- ^ "Pollution Index 2015". Numbeo. 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ "Health Effects of Air Pollution in Hong Kong". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ http://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/sites/default/files/epd/english/environmentinhk/air/studyrpts/files/final_report_mvtmpms_2012.pdf

- ^ a b "Life Expectancy Around the World". LiveScience. 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Longest Life Expectancy In World: Women In Hong Kong Now Outlast Japan". Huffington Post. 26 July 2012.

- ^ a b Room, Adrian (2005). Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company. p. 168. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Bishop, Kevin; Roberts, Annabel (1997). China's Imperial Way. China Books and Periodicals. p. 218. ISBN 962-217-511-2. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ So, Man-hing. "The Origin of the Name Hong Kong" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Kataoka, Shin; Lee, Cream (2008). "A System without a System: Cantonese Romanization Used in Hong Kong Place and Personal Names". Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics: 94.

- ^ Fairbank, John King (1953). Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854 (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 123–128. ISBN 978-0-8047-0648-3.

- ^ Hongkong Government Gazette, Notification 479, 3 September 1926

- ^ "GovHK: Residents". Hong Kong Government. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "The Trial Excavation at the Archaeological Site of Wong Tei Tung, Sham Chung, Hong Kong SAR". Hong Kong Archaeological Society. January 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 港現舊石器製造場 嶺南或為我發源地. People's Daily (in Chinese). 17 February 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Tang, Chung (2005). 考古與香港尋根 (PDF). New Asia Monthly (in Chinese). 32 (6). New Asia College: 6–8. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Li, Hui (2002). 百越遺傳結構的一元二分跡象 (PDF). Guangxi Ethnic Group Research (in Chinese). 70 (4): 26–31. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "2005 Field Archaeology on Sham Chung Site". Hong Kong Archaeological Society. January 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Declared Monuments in Hong Kong – New Territories". Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong Government. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Characteristic Culture". Invest Nanhai. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ban Biao; Ban Gu; Ban Zhao. "地理誌". Book of Han (in Chinese). Vol. Volume 28. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help) - ^ Peng, Quanmin (2001). 從考古材料看漢代深港社會. Relics From South (in Chinese). Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Keat, Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 932. ISBN 1-57607-770-5. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Archaeological Background". Hong Kong Yearbook. 21. Hong Kong Government. 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Siu Kwok-kin. 唐代及五代時期屯門在軍事及中外交通上的重要性. From Sui to Ming (in Chinese). Education Bureau, Hong Kong Government: 40–45. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Sweeting, Anthony (1990). Education in Hong Kong, Pre-1841 to 1941: Fact and Opinion. Hong Kong University Press. p. 93. ISBN 962-209-258-6.

- ^ a b Barber, Nicola (2004). Hong Kong. Gareth Stevens. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8368-5198-4.

- ^ Porter, Jonathan (1996). Macau, the Imaginary City: Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present. Westview Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8133-2836-2.

- ^ Edmonds, Richard L. (2002). China and Europe Since 1978: A European Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-52403-2.

- ^ Hayes, James (1974). "The Hong Kong Region: Its Place in Traditional Chinese Historiography and Principal Events Since the Establishment of Hsin-an County in 1573" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 14: 108–135. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Hong Kong Museum of History: "The Hong Kong Story" Exhibition Materials" (PDF). Hong Kong Museum of History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Courtauld, Caroline; Holdsworth, May; Vickers, Simon (1997). The Hong Kong Story. Oxford University Press. pp. 38–58. ISBN 978-0-19-590353-9.

- ^ Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-7007-1145-1.

- ^ John Thomson 1837–1921,Chap on Hong Kong, Illustrations of China and Its People (London,1873–1874)

- ^ Info Gov HK. "Hong Kong Gov Info." History of Hong Kong. Retrieved on 16 February 2007. Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Wiltshire, Trea (1997). Old Hong Kong. Vol. Volume II: 1901–1945 (5th ed.). FormAsia Books. p. 148. ISBN 962-7283-13-4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "History of Hong Kong". Global Times. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.