Sigma factor

A sigma factor (σ factor) is a protein needed for initiation of transcription in bacteria.[1] It is a bacterial transcription initiation factor that enables specific binding of RNA polymerase (RNAP) to gene promoters. It is homologous to archaeal transcription factor B and to eukaryotic factor TFIIB.[2] The specific sigma factor used to initiate transcription of a given gene will vary, depending on the gene and on the environmental signals needed to initiate transcription of that gene. Selection of promoters by RNA polymerase is dependent on the sigma factor that associates with it.[3]

The sigma factor, together with RNA polymerase, is known as the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Every molecule of RNA polymerase holoenzyme contains exactly one sigma factor subunit, which in the model bacterium Escherichia coli is one of those listed below. The number of sigma factors varies between bacterial species.[1][4] E. coli has seven sigma factors. Sigma factors are distinguished by their characteristic molecular weights. For example, σ70 is the sigma factor with a molecular weight of 70 kDa.

The sigma factor in the RNA polymerase holoenzyme complex is required for the initiation of transcription, although once that stage is finished, it is dissociated from the complex and the RNAP continues elongation on its own.

Specialized sigma factors

Different sigma factors are utilized under different environmental conditions. These specialized sigma factors bind the promoters of genes appropriate to the environmental conditions, increasing the transcription of those genes.

Sigma factors in E. coli:

- σ70(RpoD) – σA – the "housekeeping" sigma factor or also called as primary sigma factor, transcribes most genes in growing cells. Every cell has a "housekeeping" sigma factor that keeps essential genes and pathways operating.[1] In the case of E. coli and other gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, the "housekeeping" sigma factor is σ70.[1] Genes recognized by σ70 all contain similar promoter consensus sequences consisting of two parts.[1] Relative to the DNA base corresponding to the start of the RNA transcript, the consensus promoter sequences are characteristically centered at 10 and 35 nucleotides before the start of transcription (−10 and −35).

- σ19 (FecI) – the ferric citrate sigma factor, regulates the fec gene for iron transport

- σ24 (RpoE) – the extracytoplasmic/extreme heat stress sigma factor

- σ28 (RpoF) – the flagellar sigma factor

- σ32 (RpoH) – the heat shock sigma factor, it is turned on when the bacteria are exposed to heat. Due to the higher expression, the factor will bind with a high probability to the polymerase-core-enzyme. Doing so, other heatshock proteins are expressed, which enable the cell to survive higher temperatures. Some of the enzymes that are expressed upon activation of σ32 are chaperones, proteases and DNA-repair enzymes.

- σ38 (RpoS) – the starvation/stationary phase sigma factor

- σ54 (RpoN) – the nitrogen-limitation sigma factor

There are also anti-sigma factors that inhibit the function of sigma factors and anti-anti-sigma factors that restore sigma factor function.

Structure

Sigma factors have four main regions that are generally conserved:

N-terminus --------------------- C-terminus

1.1 2 3 4

| Sigma70 region 1.1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r1_1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03979 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR007127 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Sigma70 region 1.2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus RNA polymerase sigma subunit fragment containing regions 1.2 to 3.1 | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r1_2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00140 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR009042 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00592 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1sig / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Sigma70 region 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

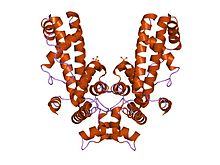

Crystal structure of a sigma70 subunit fragment from Escherichia coli RNA polymerase | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF04542 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0123 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR007627 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00592 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1sig / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Sigma70 region 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

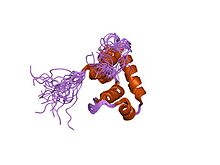

Solution structure of sigma70 region 3 from Thermotoga maritima | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r3 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF04539 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0123 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR007624 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1ku2 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Sigma70 region 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Solution structure of sigma70 region 4 from Thermotoga maritima | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r4 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF04545 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0123 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR007630 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1or7 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Sigma70 region 4.2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystal structure of Escherichia coli sigma70 region 4 bound to its -35 element DNA | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Sigma70_r4_2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08281 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0123 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013249 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1or7 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The regions are further subdivided (e.g. 2 includes 2.1, 2.2, etc.)

- Region 1.1 is found only in "primary sigma factors" (RpoD, RpoS in E.coli). It is involved in ensuring the sigma factor will only bind the promoter when it is complexed with the RNA polymerase.

- Region 2.4 recognizes and binds to the promoter −10 element (called the "Pribnow box").

- Region 4.2 recognizes and binds to the promoter −35 element.

One exception to this organization is in σ54-type sigma factors. Proteins homologous to σ54/RpoN are functional sigma factors, but they have significantly different primary amino acid sequences.

Retention during transcription elongation

The core RNA polymerase (consisting of 2 alpha (α), 1 beta (β), 1 beta-prime (β'), and 1 omega (ω) subunits) binds a sigma factor to form a complex called the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. It was previously believed that the RNA polymerase holoenzyme initiates transcription, while the core RNA polymerase alone synthesizes RNA. Thus, the accepted view was that sigma factor must dissociate upon transition from transcription initiation to transcription elongation (this transition is called "promoter escape"). This view was based on analysis of purified complexes of RNA polymerase stalled at initiation and at elongation. Finally, structural models of RNA polymerase complexes predict that, as the growing RNA product becomes longer than ~15 nucleotides, sigma must be "pushed out" of the holoenzyme, since there is a steric clash between RNA and a sigma domain. However, a recent study has shown that σ70 can remain attached in complex with the core RNA polymerase, at least during early elongation.[5] Indeed, the phenomenon of promoter-proximal pausing indicates that sigma plays roles during early elongation. All studies are consistent with the assumption that promoter escape reduces the lifetime of the sigma-core interaction from very long at initiation (too long to be measured in a typical biochemical experiment) to a shorter, measurable lifetime upon transition to elongation.

σ cycle

It long has been thought that the σ factor obligatorily leaves the core enzyme once it has initiated transcription, allowing the free σ to link to another core enzyme and initiate transcription at another site. Thus, the σ cycles from one core to another. However, Richard Ebright and coworkers, using fluorescence resonance energy transfer, later showed that the σ does not obligatorily leave the core.[5] Instead, the σ changes its binding with the core during initiation and elongation. Therefore, the σ cycles between a strongly bound state during initiation and a weakly bound state during elongation.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Gruber TM, Gross CA (2003). "Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space". Annual Review of Microbiology. 57: 441–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913. PMID 14527287.

- ^ Burton SP, Burton ZF (6 November 2014). "The σ enigma: bacterial σ factors, archaeal TFB and eukaryotic TFIIB are homologs". Transcription. 5 (4): e967599. doi:10.4161/21541264.2014.967599. PMC 4581349. PMID 25483602.

- ^ Ho TD, Ellermeier CD (April 2012). "Extra cytoplasmic function σ factor activation". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 15 (2): 182–8. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2012.01.001. PMC 3320685. PMID 22381678.

- ^ Sharma UK, Chatterji D (September 2010). "Transcriptional switching in Escherichia coli during stress and starvation by modulation of sigma activity". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 34 (5): 646–57. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00223.x. PMID 20491934.

- ^ a b Kapanidis AN, Margeat E, Laurence TA, Doose S, Ho SO, Mukhopadhyay J, Kortkhonjia E, Mekler V, Ebright RH, Weiss S (November 2005). "Retention of transcription initiation factor sigma70 in transcription elongation: single-molecule analysis". Molecular Cell. 20 (3): 347–56. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.012. PMID 16285917.

External links

- Sigma+Factor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)