Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

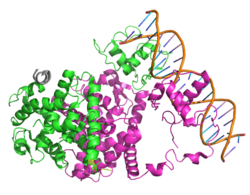

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ or PPARG), also known as the glitazone receptor, or NR1C3 (nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group C, member 3) is a type II nuclear receptor (protein regulating genes) that in humans is encoded by the PPARG gene.[5][6][7]

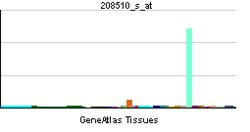

Tissue distribution

PPARG is mainly present in adipose tissue, colon and macrophages. Two isoforms of PPARG are detected in the human and in the mouse: PPAR-γ1 (found in nearly all tissues except muscle) and PPAR-γ2 (mostly found in adipose tissue and the intestine).[8][9]

Gene expression

This gene encodes a member of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) subfamily of nuclear receptors. PPARs form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) and these heterodimers regulate transcription of various genes. Three subtypes of PPARs are known: PPAR-alpha, PPAR-delta, and PPAR-gamma. The protein encoded by this gene is PPAR-gamma and is a regulator of adipocyte differentiation. Alternatively spliced transcript variants that encode different isoforms have been described.[10]

The activity PPARG can be regulated via phosphorylation through the MEK/ERK pathway. This modification decreases transcriptional activity of PPARG and leads to diabetic gene modifications, and results in insulin insensitivity. For example, the phosphorylation of serine 112 will inhibit PPARG function, and enhance adipogenic potential of fibroblasts.[11]

Function

PPARG regulates fatty acid storage and glucose metabolism. The genes activated by PPARG stimulate lipid uptake and adipogenesis by fat cells. PPARG knockout mice are devoid of adipose tissue, establishing PPARG as a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation.[12]

PPARG increases insulin sensitivity by enhancing storage of fatty acids in fat cells (reducing lipotoxicity), by enhancing adiponectin release from fat cells, by inducing FGF21,[12] and by enhancing nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate production through upregulation of the CD38 enzyme.[13]

PPARG promotes anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage activation in mice.[14]

Adiponectin induces ABCA1-mediated reverse cholesterol transport by activation of PPAR-γ and LXRα/β.[15]

Many naturally occurring agents directly bind with and activate PPAR gamma. These agents include various polyunsaturated fatty acids like arachidonic acid and arachidonic acid metabolites such as certain members of the 5-hydroxyicosatetraenoicacid and 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid family, e.g. 5-oxo-15(S)-HETE and 5-oxo-ETE or 15-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid family including 15(S)-HETE, 15(R)-HETE, and 15(S)-HpETE.[16][17][18] The phytocannabinoid tetrahydrocannabinol (THC),[19] its metabolite THC-COOH, and its synthetic analog ajulemic acid (AJA).[20] The activation of PPAR gamma by these and other ligands may be responsible for inhibiting the growth of cultured human breast, gastric, lung, prostate and other cancer cell lines.[21]

During embryogenesis, PPARG first substantially expresses in interscapular brown fat pad.[22] The depletion of PPARG will result in embryonic lethality at E10.5, due to the vascular anomalies in placenta, with no permeation of fetal blood vessels and dilation and rupture of maternal blood sinuses.[23] The expression PPARG can be detected in placenta as early as E8.5 and through the remainder of gestation, mainly located in the primary trophoblast cell in the human placenta.[22] PPARG is required for epithelial differentiation of trophoblast tissue, which is critical for proper placenta vascularization. PPARG agonists inhibit extravillous cytotrophoblast invasion. PPARG is also required for the accumulation of lipid droplets by the placenta.[11]

Interactions

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma has been shown to interact with:

Clinical relevance

PPAR-gamma has been implicated in the pathology of numerous diseases including obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cancer. PPAR-gamma agonists have been used in the treatment of hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycemia.[34][35] PPAR-gamma decreases the inflammatory response of many cardiovascular cells, particularly endothelial cells.[36] PPAR-gamma activates the PON1 gene, increasing synthesis and release of paraoxonase 1 from the liver, reducing atherosclerosis.[37]

Low PPAR-gamma reduces the capacity of adipose tissue to store fat, resulting in increased storage of fat in nonadipose tissue (lipotoxicity).[38] A soy protein diet increases adipose tissue PPAR-gamma, thereby reducing lipotoxicity.[38]

Many insulin sensitizing drugs (namely, the thiazolidinediones) used in the treatment of diabetes activate PPARG as a means to lower serum glucose without increasing pancreatic insulin secretion. Activation of PPARG is more effective for skeletal muscle insulin resistance than for insulin resistance of the liver.[39] Different classes of compounds which activate PPARG weaker than thiazolidinediones (the so-called "partial agonists of PPARgamma") are currently studied with the hope that such compounds would be still effective hypoglycemic agents but with fewer side effects.[40]

The medium-chain triglyceride decanoic acid has been shown to be a partially-activating PPAR-gamma ligand that does not increase adipogenesis.[41] Activation of PPAR-gamma by decanoic acid has been shown to increase mitochondrial number, increase the mitochondrial enzyme citrate synthase, increase complex I activity in mitochondria, and increase activity of the antioxidant enzyme catalase.[42]

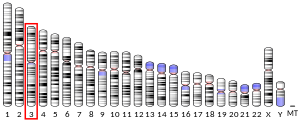

A fusion protein of PPAR-γ1 and the thyroid transcription factor PAX8 is present in approximately one-third of follicular thyroid carcinomas, to be specific those cancers with a chromosomal translocation of t(2;3)(q13;p25), which permits juxtaposition of portions of both genes.[43][44]

The phytocannabinoid cannabidiol (CBD) has been shown to activate PPAR gamma in in vitro and in vivo models.[45][46] The cannabinoid carboxylic acids THCA, CBDA and CBGA activate PAARy more efficient than their decarboxylated products; however, THCA was the acid found with highest activity. As a synthetic analog of THC‐COOH, the major non‐psychotropic metabolite of THC, ajulemic acid also is a potent PPARγ agonist. The carboxylic acid group is critical for a stronger and a long activation time.[47]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000132170 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000000440 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Greene ME, Blumberg B, McBride OW, Yi HF, Kronquist K, Kwan K, et al. (1995). "Isolation of the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma cDNA: expression in hematopoietic cells and chromosomal mapping". Gene Expression. 4 (4–5): 281–99. PMC 6134382. PMID 7787419.

- ^ Elbrecht A, Chen Y, Cullinan CA, Hayes N, Leibowitz MD, Moller DE, Berger J (July 1996). "Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of human peroxisome proliferator activated receptors gamma 1 and gamma 2". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 224 (2): 431–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1996.1044. PMID 8702406.

- ^ Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP, Chatterjee VK, Glass CK, Gonzalez FJ, et al. (December 2006). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 58 (4): 726–41. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.5. PMID 17132851. S2CID 2240461.

- ^ Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspé E, Schoonjans K, Lefebvre AM, Saladin R, et al. (July 1997). "The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (30): 18779–89. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. PMID 9228052.

- ^ Park YK, Wang L, Giampietro A, Lai B, Lee JE, Ge K (January 2017). "Distinct Roles of Transcription Factors KLF4, Krox20, and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ in Adipogenesis". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 37 (2): 18779–89. doi:10.1128/MCB.00554-16. PMC 5214852. PMID 27777310.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: PPARG peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma".

- ^ a b Suwaki N, Masuyama H, Masumoto A, Takamoto N, Hiramatsu Y (April 2007). "Expression and potential role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in the placenta of diabetic pregnancy". Placenta. 28 (4): 315–23. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2006.04.002. PMID 16753211.

- ^ a b Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, Evans RM (May 2013). "PPARγ signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future". Nature Medicine. 19 (5): 557–66. doi:10.1038/nm.3159. PMC 3870016. PMID 23652116.

- ^ Song EK, Lee YR, Kim YR, Yeom JH, Yoo CH, Kim HK, et al. (December 2012). "NAADP mediates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and insulin sensitization by PPARγ in adipocytes". Cell Reports. 2 (6): 1607–19. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.018. PMID 23177620.

- ^ a b Peluso I, Morabito G, Urban L, Ioannone F, Serafini M (December 2012). "Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis development: the central role of LDL and oxidative burst". Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 12 (4): 351–60. doi:10.2174/187153012803832602. PMID 23061409.

- ^ Hafiane A, Gasbarrino K, Daskalopoulou SS (November 2019). "The role of adiponectin in cholesterol efflux and HDL biogenesis and metabolism". Metabolism. 100: 153953. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.153953. PMID 31377319.

- ^ Dreyer C, Keller H, Mahfoudi A, Laudet V, Krey G, Wahli W (1993). "Positive regulation of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by fatty acids through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR)". Biology of the Cell. 77 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/s0248-4900(05)80176-5. PMID 8390886.

- ^ O'Flaherty JT, Rogers LC, Paumi CM, Hantgan RR, Thomas LR, Clay CE, et al. (October 2005). "5-Oxo-ETE analogs and the proliferation of cancer cells". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1736 (3): 228–36. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.08.009. PMID 16154383.

- ^ Naruhn S, Meissner W, Adhikary T, Kaddatz K, Klein T, Watzer B, et al. (February 2010). "15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is a preferential peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta agonist". Molecular Pharmacology. 77 (2): 171–84. doi:10.1124/mol.109.060541. PMID 19903832. S2CID 30996954.

- ^ O'Sullivan SE, Tarling EJ, Bennett AJ, Kendall DA, Randall MD (November 2005). "Novel time-dependent vascular actions of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 337 (3): 824–31. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.121. PMID 16213464.

- ^ Liu J, Li H, Burstein SH, Zurier RB, Chen JD (May 2003). "Activation and binding of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by synthetic cannabinoid ajulemic acid". Molecular Pharmacology. 63 (5): 983–92. doi:10.1124/mol.63.5.983. PMID 12695526.

- ^ Krishnan A, Nair SA, Pillai MR (September 2007). "Biology of PPAR gamma in cancer: a critical review on existing lacunae". Current Molecular Medicine. 7 (6): 532–40. doi:10.2174/156652407781695765. PMID 17896990.

- ^ a b Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, et al. (October 1999). "PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development". Molecular Cell. 4 (4): 585–95. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. PMID 10549290.

- ^ Schaiff WT, Barak Y, Sadovsky Y (April 2006). "The pleiotropic function of PPAR gamma in the placenta". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 249 (1–2): 10–5. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.02.009. PMID 16574314. S2CID 54322301.

- ^ Brendel C, Gelman L, Auwerx J (June 2002). "Multiprotein bridging factor-1 (MBF-1) is a cofactor for nuclear receptors that regulate lipid metabolism". Molecular Endocrinology. 16 (6): 1367–77. doi:10.1210/mend.16.6.0843. PMID 12040021.

- ^ Berger J, Patel HV, Woods J, Hayes NS, Parent SA, Clemas J, et al. (April 2000). "A PPARgamma mutant serves as a dominant negative inhibitor of PPAR signaling and is localized in the nucleus". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 162 (1–2): 57–67. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00211-2. PMID 10854698. S2CID 20343538.

- ^ Gampe RT, Montana VG, Lambert MH, Miller AB, Bledsoe RK, Milburn MV, et al. (March 2000). "Asymmetry in the PPARgamma/RXRalpha crystal structure reveals the molecular basis of heterodimerization among nuclear receptors". Molecular Cell. 5 (3): 545–55. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80448-7. PMID 10882139.

- ^ a b c Fajas L, Egler V, Reiter R, Hansen J, Kristiansen K, Debril MB, et al. (December 2002). "The retinoblastoma-histone deacetylase 3 complex inhibits PPARgamma and adipocyte differentiation". Developmental Cell. 3 (6): 903–10. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00360-X. PMID 12479814.

- ^ a b c d Kodera Y, Takeyama K, Murayama A, Suzawa M, Masuhiro Y, Kato S (October 2000). "Ligand type-specific interactions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with transcriptional coactivators". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (43): 33201–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.C000517200. PMID 10944516.

- ^ Franco PJ, Li G, Wei LN (August 2003). "Interaction of nuclear receptor zinc finger DNA binding domains with histone deacetylase". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 206 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(03)00254-5. PMID 12943985. S2CID 19487189.

- ^ Heinlein CA, Ting HJ, Yeh S, Chang C (June 1999). "Identification of ARA70 as a ligand-enhanced coactivator for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (23): 16147–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.23.16147. PMID 10347167.

- ^ Nishizawa H, Yamagata K, Shimomura I, Takahashi M, Kuriyama H, Kishida K, et al. (January 2002). "Small heterodimer partner, an orphan nuclear receptor, augments peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transactivation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (2): 1586–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M104301200. PMID 11696534.

- ^ Wallberg AE, Yamamura S, Malik S, Spiegelman BM, Roeder RG (November 2003). "Coordination of p300-mediated chromatin remodeling and TRAP/mediator function through coactivator PGC-1alpha". Molecular Cell. 12 (5): 1137–49. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00391-5. PMID 14636573.

- ^ Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Wu Z, Fan M, Xu J, O'Malley B, Spiegelman BM (November 1999). "Activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1 through transcription factor docking". Science. 286 (5443): 1368–71. doi:10.1126/science.286.5443.1368. PMID 10558993.

- ^ Lehrke M, Lazar MA (December 2005). "The many faces of PPARgamma". review. Cell. 123 (6): 993–9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. PMID 16360030. S2CID 18526710.

- ^ Kim JH, Song J, Park KW (March 2015). "The multifaceted factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in metabolism, immunity, and cancer". review. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 38 (3): 302–12. doi:10.1007/s12272-015-0559-x. PMID 25579849. S2CID 12296573.

- ^ Hamblin M, Chang L, Fan Y, Zhang J, Chen YE (June 2009). "PPARs and the cardiovascular system". review. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 11 (6): 1415–52. doi:10.1089/ARS.2008.2280. PMC 2737093. PMID 19061437.

- ^ Khateeb J, Gantman A, Kreitenberg AJ, Aviram M, Fuhrman B (January 2010). "Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) expression in hepatocytes is upregulated by pomegranate polyphenols: a role for PPAR-gamma pathway". primary. Atherosclerosis. 208 (1): 119–25. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.051. PMID 19783251.

- ^ a b Tovar AR, Torres N (March 2010). "The role of dietary protein on lipotoxicity". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1801 (3): 367–71. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.007. PMID 19800415.

- ^ Abdul-Ghani MA, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA (May 2006). "Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose". review. Diabetes Care. 29 (5): 1130–9. doi:10.2337/dc05-2179. PMID 16644654.

- ^ Chigurupati S, Dhanaraj SA, Balakumar P (May 2015). "A step ahead of PPARγ full agonists to PPARγ partial agonists: therapeutic perspectives in the management of diabetic insulin resistance". review. European Journal of Pharmacology. 755: 50–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.043. PMID 25748601.

- ^ Malapaka RR, Khoo S, Zhang J, Choi JH, Zhou XE, Xu Y, et al. (January 2012). "Identification and mechanism of 10-carbon fatty acid as modulating ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors". primary. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (1): 183–95. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.294785. PMC 3249069. PMID 22039047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hughes SD, Kanabus M, Anderson G, Hargreaves IP, Rutherford T, O'Donnell M, et al. (May 2014). "The ketogenic diet component decanoic acid increases mitochondrial citrate synthase and complex I activity in neuronal cells". primary. Journal of Neurochemistry. 129 (3): 426–33. doi:10.1111/jnc.12646. PMID 24383952.

- ^ Kroll TG, Sarraf P, Pecciarini L, Chen CJ, Mueller E, Spiegelman BM, Fletcher JA (August 2000). "PAX8-PPARgamma1 fusion oncogene in human thyroid carcinoma [corrected]". primary. Science. 289 (5483): 1357–60. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1357K. doi:10.1126/science.289.5483.1357. PMID 10958784.

- ^ Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, eds. (2007). "Chapter 20: The Endocrine System". Robbins Basic Pathology. review (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ Ramer R, Heinemann K, Merkord J, Rohde H, Salamon A, Linnebacher M, Hinz B (January 2013). "COX-2 and PPAR-γ confer cannabidiol-induced apoptosis of human lung cancer cells". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 12 (1): 69–82. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0335. PMID 23220503.

- ^ De Filippis D, Esposito G, Cirillo C, Cipriano M, De Winter BY, Scuderi C, et al. (December 2011). "Cannabidiol reduces intestinal inflammation through the control of neuroimmune axis". PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28159. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628159D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028159. PMC 3232190. PMID 22163000.

- ^ Nadal X, Del Río C, Casano S, Palomares B, Ferreiro-Vera C, Navarrete C, et al. (December 2017). "Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid is a potent PPARγ agonist with neuroprotective activity". British Journal of Pharmacology. 174 (23): 4263–4276. doi:10.1111/bph.14019. PMC 5731255. PMID 28853159.

Further reading

- Qi C, Zhu Y, Reddy JK (2001). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, coactivators, and downstream targets". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 32 Spring (1–3): 187–204. doi:10.1385/cbb:32:1-3:187. PMID 11330046.

- Kadowaki T, Hara K, Kubota N, Tobe K, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, et al. (2002). "The role of PPARgamma in high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance". Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 16 (1): 41–5. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00206-9. PMID 11872365.

- Wakino S, Law RE, Hsueh WA (2002). "Vascular protective effects by activation of nuclear receptor PPARgamma". Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 16 (1): 46–9. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00197-0. PMID 11872366.

- Takano H, Komuro I (2002). "Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in cardiovascular disease". Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 16 (1): 108–14. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00203-3. PMID 11872377.

- Stumvoll M, Häring H (August 2002). "The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 Pro12Ala polymorphism". Diabetes. 51 (8): 2341–7. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2341. PMID 12145143.

- Koeffler HP (January 2003). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and cancers". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (1): 1–9. PMID 12538445.

- Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM (February 2003). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator". Endocrine Reviews. 24 (1): 78–90. doi:10.1210/er.2002-0012. PMID 12588810.

- Takano H, Hasegawa H, Nagai T, Komuro I (May 2003). "The role of PPARgamma-dependent pathway in the development of cardiac hypertrophy". Drugs of Today. 39 (5): 347–57. doi:10.1358/dot.2003.39.5.799458. PMID 12861348.

- Rangwala SM, Lazar MA (June 2004). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (6): 331–6. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.012. PMID 15165749.

- Cuzzocrea S (July 2004). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma ligands and ischemia and reperfusion injury". Vascular Pharmacology. 41 (6): 187–95. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2004.10.004. PMID 15653094.

- Savage DB (January 2005). "PPAR gamma as a metabolic regulator: insights from genomics and pharmacology". Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 7 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S1462399405008793. PMID 15673477.

- Pégorier JP (April 2005). "[PPAR receptors and insulin sensitivity: new agonists in development]". Annales d'Endocrinologie. 66 (2 Pt 2): 1S10–7. PMID 15959400.

- Tsai YS, Maeda N (April 2005). "PPARgamma: a critical determinant of body fat distribution in humans and mice". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 15 (3): 81–5. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.002. PMID 16039966.

- Gurnell M (December 2005). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the regulation of adipocyte function: lessons from human genetic studies". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 19 (4): 501–23. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2005.10.001. PMID 16311214.

- Cecil JE, Watt P, Palmer CN, Hetherington M (June 2006). "Energy balance and food intake: the role of PPARgamma gene polymorphisms". Physiology & Behavior. 88 (3): 227–33. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.028. PMID 16777151. S2CID 54243343.

- Rousseaux C, Desreumaux P (2007). "[The peroxisome-proliferator-activated gamma receptor and chronic inflammatory bowel disease (PPARgamma and IBD)]". Journal de la Societe de Biologie. 200 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1051/jbio:2006015. PMID 17151549.

- Eriksson JG (April 2007). "Gene polymorphisms, size at birth, and the development of hypertension and type 2 diabetes". The Journal of Nutrition. 137 (4): 1063–5. doi:10.1093/jn/137.4.1063. PMID 17374678.

- Tönjes A, Stumvoll M (July 2007). "The role of the Pro12Ala polymorphism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes risk". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 10 (4): 410–4. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3281e389d9. PMID 17563457. S2CID 30323803.

- Burgermeister E, Seger R (July 2007). "MAPK kinases as nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttles for PPARgamma". Cell Cycle. 6 (13): 1539–48. doi:10.4161/cc.6.13.4453. PMID 17611413.

- Papageorgiou E, Pitulis N, Msaouel P, Lembessis P, Koutsilieris M (August 2007). "The non-genomic crosstalk between PPAR-gamma ligands and ERK1/2 in cancer cell lines". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 11 (8): 1071–85. doi:10.1517/14728222.11.8.1071. PMID 17665979. S2CID 86480850.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.