P53: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{lowercase}}{{PBB|geneid=7157}} |

{{lowercase}}{{PBB|geneid=7157}} |

||

'''p53''' (also known as '''protein 53''' or '''tumor protein 53'''), is a [[tumor suppressor]] protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TP53'' gene.<ref name="pmid6396087">{{cite journal|author=Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S|title=Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene|journal=EMBO J.|volume=3|issue=13|pages=3257–62|year=1984|month=December|pmid=6396087|pmc=557846|doi=| url=| issn=}}</ref><ref name="pmid3456488">{{cite journal|author=Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM|title=Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13|journal=Nature|volume=320|issue=6057|pages=84–5|year=1986|pmid=3456488|doi=10.1038/320084a0|url= }}</ref><ref name="pmid2047879">{{cite journal|author=Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B|title=Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein|journal=Science (journal)|volume=252|issue=5013|pages=1708–11|year=1991|month=June|pmid=2047879|doi=| url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2047879|issn=}}</ref> p53 is important in [[multicellular organism]]s, where it regulates the [[cell cycle]] and, thus, functions as a [[tumor suppressor]] that is involved in preventing [[cancer]]. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the [[genome]]", the "guardian angel gene", and the "master watchman", referring to its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.<ref name="isbn0-471-33061-2">{{cite book|author=Read, A. P.; Strachan, T.|title=Human molecular genetics 2|publisher=Wiley|location=New York|year=1999|pages=|lala lala isbn=0–471–33061–2|oclc=| doi=| chapter=Chapter 18: Cancer Genetics }}</ref> |

'''p53''' (also known as '''protein 53''' or '''tumor protein 53'''), is a [[tumor suppressor]] protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TP53'' gene.<ref name="pmid6396087">{{cite journal|author=Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S|title=Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene|journal=EMBO J.|volume=3|issue=13|pages=3257–62|year=1984|month=December|pmid=6396087|pmc=557846|doi=| url=| issn=}}</ref><ref name="pmid3456488">{{cite journal|author=Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM|title=Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13|journal=Nature|volume=320|issue=6057|pages=84–5|year=1986|pmid=3456488|doi=10.1038/320084a0|url= }}</ref><ref name="pmid2047879">{{cite journal|author=Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B|title=Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein|journal=Science (journal)|volume=252|issue=5013|pages=1708–11|year=1991|month=June|pmid=2047879|doi=| url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2047879|issn=}}</ref><ref name="pmid 3001719">{{cite journal|author=McBride OW, Merry D, Givol D |title= The gene for human p53 cellular tumor antigen is located on chromosome 17 short arm (17p13) |journal=Prof. Nat'l. Acad. Sci |volume=83 |issue= |pages=130-134 |pmid= 3001719 |doi= |url= }}</ref> p53 is important in [[multicellular organism]]s, where it regulates the [[cell cycle]] and, thus, functions as a [[tumor suppressor]] that is involved in preventing [[cancer]]. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the [[genome]]", the "guardian angel gene", and the "master watchman", referring to its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.<ref name="isbn0-471-33061-2">{{cite book|author=Read, A. P.; Strachan, T.|title=Human molecular genetics 2|publisher=Wiley|location=New York|year=1999|pages=|lala lala isbn=0–471–33061–2|oclc=| doi=| chapter=Chapter 18: Cancer Genetics }}</ref> |

||

The name p53 is in reference to its apparent [[molecular mass]]: It runs as a 53-[[kilodalton]] (kDa) protein on [[SDS-PAGE]]. But, based on calculations from its [[amino acid]] residues, p53's mass is actually only 43.7 kDa. This difference is due to the high number of [[proline]] residues in the protein, which slow its migration on [[SDS-PAGE]], thus making it appear heavier than it actually is.<ref name="pmid7107651">{{cite journal |author=Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM |title=Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs |journal=J. Biol. Chem. |volume=257 |issue=18 |pages=11176–80 |year=1982 |month=September |pmid=7107651 |doi= |url=http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7107651}}</ref> This effect is observed with p53 from a variety of species, including humans, rodents, frogs, and fish. |

The name p53 is in reference to its apparent [[molecular mass]]: It runs as a 53-[[kilodalton]] (kDa) protein on [[SDS-PAGE]]. But, based on calculations from its [[amino acid]] residues, p53's mass is actually only 43.7 kDa. This difference is due to the high number of [[proline]] residues in the protein, which slow its migration on [[SDS-PAGE]], thus making it appear heavier than it actually is.<ref name="pmid7107651">{{cite journal |author=Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM |title=Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs |journal=J. Biol. Chem. |volume=257 |issue=18 |pages=11176–80 |year=1982 |month=September |pmid=7107651 |doi= |url=http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7107651}}</ref> This effect is observed with p53 from a variety of species, including humans, rodents, frogs, and fish. |

||

Revision as of 10:05, 10 October 2010

p53 (also known as protein 53 or tumor protein 53), is a tumor suppressor protein that in humans is encoded by the TP53 gene.[1][2][3][4] p53 is important in multicellular organisms, where it regulates the cell cycle and, thus, functions as a tumor suppressor that is involved in preventing cancer. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome", the "guardian angel gene", and the "master watchman", referring to its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.[5]

The name p53 is in reference to its apparent molecular mass: It runs as a 53-kilodalton (kDa) protein on SDS-PAGE. But, based on calculations from its amino acid residues, p53's mass is actually only 43.7 kDa. This difference is due to the high number of proline residues in the protein, which slow its migration on SDS-PAGE, thus making it appear heavier than it actually is.[6] This effect is observed with p53 from a variety of species, including humans, rodents, frogs, and fish.

Nomenclature

P53 is also known as:

- UniProt name: Cellular tumor antigen p53

- Antigen NY-CO-13

- Phosphoprotein p53

- Transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53)

- Tumor suppressor p53

Gene

In humans, p53 is encoded by the TP53 gene located on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13.1).[1][2][3][4] TP53 orthologs [7] have been identified in most mammals for which complete genome data are available.

In humans, the two most common polymorphisms to occur involve the substitution of an Arginine base for a Proline base. This polymorphism arises out of a SNP mutation on the 72 codon, where a guanine base is replaced by a cytosine (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9607760)

For these mammals, the gene is located on different chromosomes:

- Chimp and orangutan, chromosome 17

- Macaque, chromosome 16

- Mouse, chromosome 11

- Rat, chromosome 10

- Dog, chromosome 5

- Cow, chromosome 19

- Pig, chromosome 12

- Horse, chromosome 11

- Opossum, chromosome 2

(Italics are used to denote the TP53 gene name and distinguish it from the protein it encodes.)

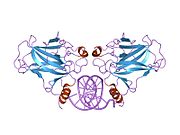

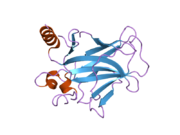

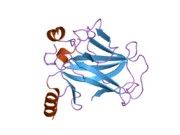

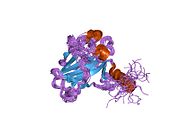

Structure

Human p53 is 393 amino acids long and has seven domains:

- N-terminal transcription-activation domain (TAD), also known as activation domain 1 (AD1), which activates transcription factors: residues 1-42.

- activation domain 2 (AD2) important for apoptotic activity: residues 43-63.

- Proline rich domain important for the apoptotic activity of p53: residues 64-92.

- central DNA-binding core domain (DBD). Contains one zinc atom and several arginine amino acids: residues 100-300.

- nuclear localization signaling domain, residues 316-325.

- homo-oligomerisation domain (OD): residues 307-355. Tetramerization is essential for the activity of p53 in vivo.

- C-terminal involved in downregulation of DNA binding of the central domain: residues 356-393.[8]

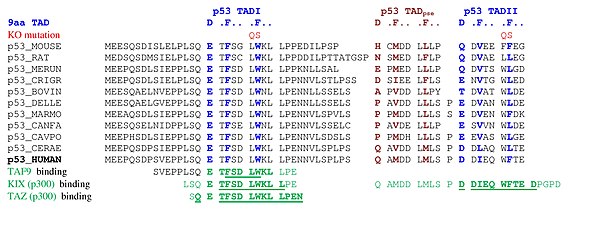

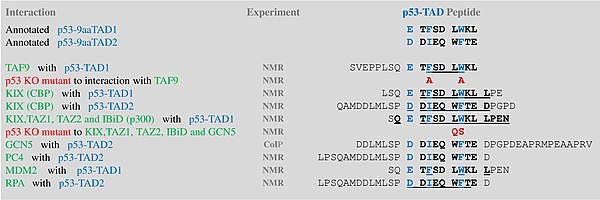

A tandem of nine-amino-acid transactivation domains (9aaTAD) was identified in the AD1 and AD2 regions of transcription factor p53.[9] KO mutations and position for p53 interaction with TFIID are listed below:[10]

9aaTADs mediate p53 interaction with general coactivators - TAF9, CBP/p300 (all four domains KIX, TAZ1, TAZ2 and IBiD), GCN5 and PC4, regulatory protein MDM2 and replication protein A (RPA).[11][12]

Mutations that deactivate p53 in cancer usually occur in the DBD. Most of these mutations destroy the ability of the protein to bind to its target DNA sequences, and thus prevents transcriptional activation of these genes. As such, mutations in the DBD are recessive loss-of-function mutations. Molecules of p53 with mutations in the OD dimerise with wild-type p53, and prevent them from activating transcription. Therefore OD mutations have a dominant negative effect on the function of p53.

Wild-type p53 is a labile protein, comprising folded and unstructured regions that function in a synergistic manner.[13]

Function

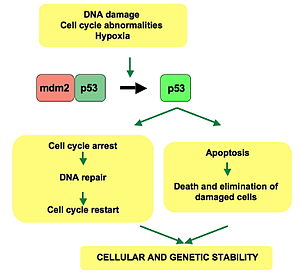

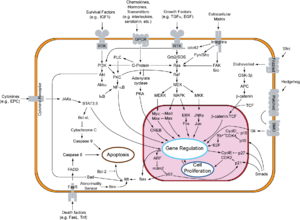

P53 has many anticancer mechanisms, and plays a role in apoptosis, genetic stability, and inhibition of angiogenesis. In its anti-cancer role, p53 works through several mechanisms:

- It can activate DNA repair proteins when DNA has sustained damage.

- It can induce growth arrest by holding the cell cycle at the G1/S regulation point on DNA damage recognition (if it holds the cell here for long enough, the DNA repair proteins will have time to fix the damage and the cell will be allowed to continue the cell cycle).

- It can initiate apoptosis, the programmed cell death, if DNA damage proves to be irreparable.

Activated p53 binds DNA and activates expression of several genes including WAF1/CIP1 encoding for p21. p21 (WAF1) binds to the G1-S/CDK (CDK2) and S/CDK complexes (molecules important for the G1/S transition in the cell cycle) inhibiting their activity.

When p21(WAF1) is complexed with CDK2 the cell cannot continue to the next stage of cell division. A mutant p53 will no longer bind DNA in an effective way, and, as a consequence, the p21 protein will not be available to act as the "stop signal" for cell division. Thus, cells will divide uncontrollably, and form tumors.[14]

Recent research has also linked the p53 and RB1 pathways, via p14ARF, raising the possibility that the pathways may regulate each other.[15]

P53 by regulating LIF has been shown to facilitate implantation in the mouse model and possibly in humans.[16]

P53 expression can be stimulated by UV light, which also causes DNA damage. In this case, p53 can initiate events leading to tanning.[17][18]

Regulation

P53 becomes activated in response to a myriad of stress types, which include but are not limited to DNA damage (induced by either UV, IR, or chemical agents such as hydrogen peroxide), oxidative stress,[19] osmotic shock, ribonucleotide depletion, and deregulated oncogene expression. This activation is marked by two major events. First, the half-life of the p53 protein is increased drastically, leading to a quick accumulation of p53 in stressed cells. Second, a conformational change forces p53 to be activated as a transcription regulator in these cells. The critical event leading to the activation of p53 is the phosphorylation of its N-terminal domain. The N-terminal transcriptional activation domain contains a large number of phosphorylation sites and can be considered as the primary target for protein kinases transducing stress signals.

The protein kinases that are known to target this transcriptional activation domain of p53 can be roughly divided into two groups. A first group of protein kinases belongs to the MAPK family (JNK1-3, ERK1-2, p38 MAPK), which is known to respond to several types of stress, such as membrane damage, oxidative stress, osmotic shock, heat shock, etc. A second group of protein kinases (ATR, ATM, CHK1 and CHK2, DNA-PK, CAK) is implicated in the genome integrity checkpoint, a molecular cascade that detects and responds to several forms of DNA damage caused by genotoxic stress. Oncogenes also stimulate p53 activation, mediated by the protein p14ARF.

In unstressed cells, p53 levels are kept low through a continuous degradation of p53. A protein called Mdm2 (also called HDM2 in humans), which is itself a product of p53, binds to p53, preventing its action and transports it from the nucleus to the cytosol. Also Mdm2 acts as ubiquitin ligase and covalently attaches ubiquitin to p53 and thus marks p53 for degradation by the proteasome. However, ubiquitylation of p53 is reversible. A ubiquitin specific protease, USP7 (or HAUSP), can cleave ubiquitin off p53, thereby protecting it from proteasome-dependent degradation. This is one means by which p53 is stabilized in response to oncogenic insults.

Phosphorylation of the N-terminal end of p53 by the above-mentioned protein kinases disrupts Mdm2-binding. Other proteins, such as Pin1, are then recruited to p53 and induce a conformational change in p53, which prevents Mdm2-binding even more. Phosphorylation also allows for binding of trancriptional coactivators, like p300 or PCAF, which then acetylate the carboxy-terminal end of p53, exposing the DNA binding domain of p53, allowing it to activate or repress specific genes. Deacetylase enzymes, such as Sirt1 and Sirt7, can deacetylate p53, leading to an inhibition of apoptosis.[20] Some oncogenes can also stimulate the transcription of proteins which bind to MDM2 and inhibit its activity.

Role in disease

If the TP53 gene is damaged, tumor suppression is severely reduced. People who inherit only one functional copy of the TP53 gene will most likely develop tumors in early adulthood, a disease known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome. The TP53 gene can also be damaged in cells by mutagens (chemicals, radiation, or viruses), increasing the likelihood that the cell will begin decontrolled division. More than 50 percent of human tumors contain a mutation or deletion of the TP53 gene.[21] Increasing the amount of p53, which may initially seem a good way to treat tumors or prevent them from spreading, is in actuality not a usable method of treatment, since it can cause premature aging.[22] However, restoring endogenous p53 function holds a lot of promise.[23] Loss of p53 creates genomic instability that most often results in the aneuploidy phenotype.[24]

Certain pathogens can also affect the p53 protein that the TP53 gene expresses. One such example, human papillomavirus (HPV), encodes a protein, E6, which binds the p53 protein and inactivates it. This, in synergy with the inactivation of another cell cycle regulator, pRb, by the HPV protein E7, allows for repeated cell division manifested in the clinical disease of warts. Certain HPV types, in particular types 16 and 18, can also lead to progression from a benign wart to low or high-grade cervical dysplasia, which are reversible forms of precancerous lesions. Persistent infection of the cervix over the years can cause irreversible changes leading to carcinoma in situ and eventually invasive cervical cancer. This results from the effects of HPV genes, particularly those encoding E6 and E7, which are the two viral oncoproteins that are preferentially retained and expressed in cervical cancers by integration of the viral DNA into the host genome.[25]

In healthy humans, the p53 protein is continually produced and degraded in the cell. The degradation of the p53 protein is, as mentioned, associated with MDM2 binding. In a negative feedback loop, MDM2 is itself induced by the p53 protein. However, mutant p53 proteins often do not induce MDM2, and are thus able to accumulate at very high concentrations. Worse, mutant p53 protein itself can inhibit normal p53 protein levels.

Discovery

P53 was identified in 1979 by Lionel Crawford, David P. Lane, Arnold Levine, and Lloyd Old, working at Imperial Cancer Research Fund (UK) Princeton University/UMDNJ (Cancer Institute of New Jersey), and Sloan-Kettering Memorial Hospital, respectively. It had been hypothesized to exist before as the target of the SV40 virus, a strain that induced development of tumors. The TP53 gene from the mouse was first cloned by Peter Chumakov of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1982,[26] and independently in 1983 by Moshe Oren (Weizmann Institute).[27] The human TP53 gene was cloned in 1984.[1]

It was initially presumed to be an oncogene due to the use of mutated cDNA following purification of tumour cell mRNA. Its character as a tumor suppressor gene was finally revealed in 1989 by Bert Vogelstein working at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.[28]

Warren Maltzman, of the Waksman Institute of Rutgers University first demonstrated that TP53 was responsive to DNA damage in the form of ultraviolet radiation.[29] In a series of publications in 1991-92, Michael Kastan, Johns Hopkins University, reported that TP53 was a critical part of a signal transduction pathway that helped cells respond to DNA damage.[30]

In 1992, Wafik El-Deiry when he was working with Bert Vogelstein at Johns Hopkins University identified the consensus sequence, to which human p53 could bind, by immunoprecipitating human genomic DNA that could be bound by baculovirus-produced human p53 protein. This sequence was published in the first issue of the journal Nature Genetics in 1992 in work that is highly cited. The consensus sequence is 5'-RRRCWWGYYY-N(0-13)-RRRCWWGYYY-3' and is located in the regulatory regions of genes that are activated by the p53 transcription factor. The presence of p53 response elements in or around genes (promoters, upstream sequences, introns) is a powerful predictor of regulation and activation of a particular gene by p53.

In 1993, p53 was voted molecule of the year by Science magazine.[31]

That same year, 1993, Wafik El-Deiry when he was working with Bert Vogelstein at Johns Hopkins University discovered p21(WAF1) as a gene regulated directly by p53. This work was reported in the most highly cited paper ever published in the journal Cell, and provided a molecular mechanism by which mammalian cells undergo growth arrest when damaged. The p21(WAF1) protein binds directly to cyclin-CDK complexes that drive forward the cell cycle and inhibits their kinase activity thereby causing cell cycle arrest to allow repair to take place. p21 can also mediate growth arrest associated with differentiation and a more permanent growth arrest associated with cellular senescence. The p21 gene contains several p53 response elements that mediate direct binding of the p53 protein, resulting in transcriptional activation of the gene encoding the p21(WAF1) protein.

Interactions

P53 has been shown to interact with

- HIPK1[32]

- Replication protein A1[33][34]

- ERCC6[35][36]

- TSG101[37]

- Protein kinase R[38]

- CFLAR[39]

- XPB[35]

- CREB binding protein[40][41][42]

- CREB1[42]

- Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9[43][44]

- Prohibitin[45]

- RPL11[46]

- Ataxia telangiectasia mutated[47][48][49][50][51]

- DNA-PKcs[51][52][53]

- ATF3,[54][55]

- HIPK2[56][57]

- HIF1A[58][59][60][61]

- MED1[62][63]

- Zif268[64]

- GPS2[65]

- EFEMP2[66]

- Promyelocytic leukemia protein[67][68][69]

- PLK3[70][71]

- TP53INP1[72][73]

- Aurora A kinase[74]

- BRE[75]

- PTTG1[76]

- CHEK1[52][77][78] CCNG1,[79]

- Cyclin H[80]

- TOP1[81][82]

- PIAS1[66][83] CDC14B[84]

- BRCA2[75][85]

- BRCA1[75][86][87][88][89]

- RCHY1[90][91]

- CDC14A[84]

- E4F1[92][93]

- PARP1[94][95]

- ZNF148[96]

- HMGB1[97][98]

- Multisynthetase complex auxiliary component p38[99]

- PRKRA[100]

- Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related[48][51]

- TP53BP1[78][101][102][103][104][105][106]

- Cdk1[107][108]

- TP53BP2,[106][109] TOP2B,[110]

- TOP2A[110]

- Bloom syndrome protein[78][111][112][113]

- BAK1[114]

- PARC[115]

- RAD51[75][116][117]

- BARD1[75]

- PSME3[118]

- Aprataxin[94]

- S100B,[119]

- UBE2I[66][120][121][122]

- PIN1[123][124]

- Small ubiquitin-related modifier 1[120][125]

- Huntingtin[126]

- PTEN[127]

- KPNB1[128]

- Cyclin-dependent kinase 7[80][129]

- ING5[130] ELL,[131]

- PTK2[132]

- NUMB[133]

- ING1[134][135]

- P16[46][92][136]

- USP7[137]

- ING4[130][138]

- YWHAZ[139]

- UBE2A[140]

- Ubiquitin C[99][118][125][141][142][143][144][145]

- Werner syndrome ATP-dependent helicase[113][146]

- GNL3[147]

- BRCC3[75]

- CCAAT/enhancer binding protein zeta[148]

- WWOX[149]

- Y box binding protein 1[150][151]

- IκBα[152]

- TATA binding protein[153][154]

- HSPA9[155]

- MDM4[156][157]

- Mdm2[40][46][67][127][134][136][158][159][160][161][162][118][163][133][164][165][166][167][168][169][170][171][172]

- GSK3B[173]

- SMN1[174]

- Heat shock protein 90kDa alpha (cytosolic), member A1[128][175][176]

- TFAP2A[177]

- ANKRD2[150]

- PLAGL1[178]

- Nucleolin[179]

- NDN[180]

- SMARCB1[181]

- EP300[41][160][182][183]

- SMARCA4,[181]

- MNAT1[129]

- TFDP1[184]

References

- ^ a b c Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S (1984). "Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene". EMBO J. 3 (13): 3257–62. PMC 557846. PMID 6396087.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid6396087" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM (1986). "Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13". Nature. 320 (6057): 84–5. doi:10.1038/320084a0. PMID 3456488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B (1991). "Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein". Science (journal). 252 (5013): 1708–11. PMID 2047879.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid2047879" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b McBride OW, Merry D, Givol D. "The gene for human p53 cellular tumor antigen is located on chromosome 17 short arm (17p13)". Prof. Nat'l. Acad. Sci. 83: 130–134. PMID 3001719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Read, A. P.; Strachan, T. (1999). "Chapter 18: Cancer Genetics". Human molecular genetics 2. New York: Wiley.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lala lala isbn=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM (1982). "Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (18): 11176–80. PMID 7107651.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: TP53 coding sequence".

- ^ Harms KL, Chen X (2005). "The C terminus of p53 family proteins is a cell fate determinant". Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 (5): 2014–30. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.5.2014-2030.2005. PMC 549381. PMID 15713654.

- ^ Piskacek S, Gregor M, Nemethova M, Grabner M, Kovarik P, Piskacek M (2007). "Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain: establishment and prediction utilities". Genomics. 89 (6): 756–68. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.003. PMID 17467953.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Uesugi M, Nyanguile O, Lu H, Levine AJ, Verdine GL (1997). "Induced alpha helix in the VP16 activation domain upon binding to a human TAF". Science (journal). 277 (5330): 1310–3. doi:10.1126/science.277.5330.1310. PMID 9271577.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Uesugi M, Verdine GL (1999). "The alpha-helical FXXPhiPhi motif in p53: TAF interaction and discrimination by MDM2". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (26): 14801–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.26.14801. PMC 24728. PMID 10611293.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Choi Y, Asada S, Uesugi M (2000). "Divergent hTAFII31-binding motifs hidden in activation domains". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (21): 15912–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.21.15912. PMID 10821850.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link); Venot C, Maratrat M, Sierra V, Conseiller E, Debussche L (1999). "Definition of a p53 transactivation function-deficient mutant and characterization of two independent p53 transactivation subdomains". Oncogene. 18 (14): 2405–10. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202539. PMID 10327062.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Lin J, Chen J, Elenbaas B, Levine AJ (1994). "Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein". Genes Dev. 8 (10): 1235–46. doi:10.1101/gad.8.10.1235. PMID 7926727.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Piskacek S, Gregor M, Nemethova M, Grabner M, Kovarik P, Piskacek M (2007). "Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain: establishment and prediction utilities". Genomics. 89 (6): 756–68. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.003. PMID 17467953.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Piskacek M (2009-11-05). "9aaTAD is a common transactivation domain recruits multiple general coactivators TAF9, MED15, CBP/p300 and GCN5". Nature Precedings Pre-publication. doi:10.1038/npre.2009.3488.2.; Piskacek M (2009-11-05). "9aaTADs mimic DNA to interact with a pseudo-DNA Binding Domain KIX of Med15 (Molecular Chameleons)". Nature Precedings Pre-publication. doi:10.1038/npre.2009.3939.1.; Piskacek M; Piskacek, Martin (2009-11-20). "9aaTAD Prediction result (2006)". Nature Precedings Pre-publication. doi:10.1038/npre.2009.3984.1. - ^ The prediction for 9aaTADs (for both acidic and hydrophilic transactivation domains) is available online from ExPASy http://us.expasy.org/tools/ and EMBnet Spain http://www.es.embnet.org/Services/EMBnetAT/htdoc/9aatad/

- ^ Bell S, Klein C, Müller L, Hansen S, Buchner J (2002). "p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state". J. Mol. Biol. 322 (5): 917–27. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00848-3. PMID 12367518.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information. "The p53 tumor suppressor protein". Genes and Disease. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bates S, Phillips AC, Clark PA, Stott F, Peters G, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH (1998). "p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53". Nature. 395 (6698): 124–5. doi:10.1038/25867. PMID 9744267.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wenwei Hu, Zhaohui Feng, Angelika K. Teresky1, Arnold J. Levine (November 29, 2007). "p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF". Nature 450, 721-724.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Genome's guardian gets a tan started". New Scientist. March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D'Orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter SR, Fisher DE (2007). "Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation". Cell. 128 (5): 853–64. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.045. PMID 17350573.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Han ES, Muller FL, Pérez VI, Qi W, Liang H, Xi L, Fu C, Doyle E, Hickey M, Cornell J, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, Van Remmen H, Richardson A (2008). "The in vivo gene expression signature of oxidative stress". Physiol. Genomics. 34 (1): 112–26. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00239.2007. PMC 2532791. PMID 18445702.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vakhrusheva O, Smolka C, Gajawada P, Kostin S, Boettger T, Kubin T, Braun T, Bober (2008). "Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice". Circ. Res. 102 (6): 703–10. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. PMID 18239138.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC (1991). "p53 mutations in human cancers". Science. 253 (5015): 49–53. doi:10.1126/science.1905840. PMID 1905840.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, Lu X, Soron G, Cooper B, Brayton C, Hee Park S, Thompson T, Karsenty G, Bradley A, Donehower LA (2002). "p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes". Nature. 415 (6867): 45–53. doi:10.1038/415045a. PMID 11780111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T (2007). "Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo". Nature. 445 (7128): 661–5. doi:10.1038/nature05541. PMID 17251932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clemens A. Schmitt; Fridman, JS; Yang, M; Baranov, E; Hoffman, RM; Lowe, SW (2002). "Dissecting p53 tumor suppressor functions in vivo". Cancer Cell. 1 (3): 289–298. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00047-8. PMID 12086865.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Angeletti PC, Zhang L, Wood C (2008). "The viral etiology of AIDS-associated malignancies". Adv. Pharmacol. 56: 509–57. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56016-3. PMC 2149907. PMID 18086422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chumakov P, Iotsova V, Georgiev G (1982). "Isolation of a plasmid clone containing the mRNA sequence for mouse nonviral T-antigen". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 267 (5): 1272–5. PMID 6295732.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oren M, Levine AJ (1983). "Molecular cloning of a cDNA specific for the murine p53 cellular tumor antigen". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80 (1): 56–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.1.56. PMC 393308. PMID 6296874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Baker SJ, Fearon ER, Nigro JM, Hamilton SR, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, vanTuinen P, Ledbetter DH, Barker DF, Nakamura Y, White R, Vogelstein B (1989). "Chromosome 17 deletions and p53 gene mutations in colorectal carcinomas". Science (journal). 244 (4901): 217–21. doi:10.1126/science.2649981. PMID 2649981.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maltzman W, Czyzyk L (1984). "UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells". Mol Cell Biol. 4 (9): 1689–94. PMC 368974. PMID 6092932.

- ^ Kastan MB, Kuerbitz SJ (1993). "Control of G1 arrest after DNA damage". Environ. Health Perspect. 101 Suppl 5. Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 101: 55–8. doi:10.2307/3431842. PMC 1519427. PMID 8013425.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Koshland DE (1993). "Molecule of the year". Science. 262 (5142): 1953. doi:10.1126/science.8266084. PMID 8266084.

- ^ Kondo, Seiji (2003). "Characterization of cells and gene-targeted mice deficient for the p53-binding kinase homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 (HIPK1)". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (9): 5431–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530308100. PMC 154362. PMID 12702766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Romanova, Larisa Y (2004). "The interaction of p53 with replication protein A mediates suppression of homologous recombination". Oncogene. 23 (56): 9025–33. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207982. PMID 15489903.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Riva, F (2001). "UV-induced DNA incision and proliferating cell nuclear antigen recruitment to repair sites occur independently of p53-replication protein A interaction in p53 wild type and mutant ovarian carcinoma cells". Carcinogenesis. 22 (12): 1971–8. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.12.1971. PMID 11751427.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wang, X W (1995). "p53 modulation of TFIIH-associated nucleotide excision repair activity". Nat. Genet. 10 (2): 188–95. doi:10.1038/ng0695-188. PMID 7663514.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yu, A (2000). "Activation of p53 or loss of the Cockayne syndrome group B repair protein causes metaphase fragility of human U1, U2, and 5S genes". Mol. Cell. 5 (5): 801–10. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80320-2. PMID 10882116.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Li, L (2001). "A TSG101/MDM2 regulatory loop modulates MDM2 degradation and MDM2/p53 feedback control". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (4): 1619–24. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1619. PMC 29306. PMID 11172000.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cuddihy, A R (1999). "The double-stranded RNA activated protein kinase PKR physically associates with the tumor suppressor p53 protein and phosphorylates human p53 on serine 392 in vitro". Oncogene. 18 (17): 2690–702. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202620. PMID 10348343.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abedini, Mohammad R (2008). "Cisplatin induces p53-dependent FLICE-like inhibitory protein ubiquitination in ovarian cancer cells". Cancer Res. 68 (12): 4511–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0673. PMID 18559494.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ito, Akihiro (2002). "MDM2-HDAC1-mediated deacetylation of p53 is required for its degradation". EMBO J. 21 (22): 6236–45. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf616. PMC 137207. PMID 12426395.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Livengood, Jill A (2002). "p53 Transcriptional activity is mediated through the SRC1-interacting domain of CBP/p300". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (11): 9054–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108870200. PMID 11782467.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Giebler, H A (2000). "p53 recruitment of CREB binding protein mediated through phosphorylated CREB: a novel pathway of tumor suppressor regulation". Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (13): 4849–58. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.13.4849-4858.2000. PMC 85936. PMID 10848610.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hu, M C (1997). "JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3 are p53 N-terminal serine 34 kinases". Oncogene. 15 (19): 2277–87. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201401. PMID 9393873.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lin, Yenshou (2002). "Death-associated protein 4 binds MST1 and augments MST1-induced apoptosis". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (50): 47991–8001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202630200. PMID 12384512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fusaro, Gina (2003). "Prohibitin induces the transcriptional activity of p53 and is exported from the nucleus upon apoptotic signaling". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (48): 47853–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305171200. PMID 14500729.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Zhang, Yanping (2003). "Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (23): 8902–12. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.23.8902-8912.2003. PMC 262682. PMID 14612427.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kang, Jian (2005). "Functional interaction of H2AX, NBS1, and p53 in ATM-dependent DNA damage responses and tumor suppression". Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 (2): 661–70. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.2.661-670.2005. PMC 543410. PMID 15632067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Fabbro, Megan (2004). "BRCA1-BARD1 complexes are required for p53Ser-15 phosphorylation and a G1/S arrest following ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (30): 31251–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405372200. PMID 15159397.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Khanna, K K (1998). "ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction". Nat. Genet. 20 (4): 398–400. doi:10.1038/3882. PMID 9843217.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Westphal, C H (1997). "Genetic interactions between atm and p53 influence cellular proliferation and irradiation-induced cell cycle checkpoints". Cancer Res. 57 (9): 1664–7. PMID 9135004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Kim, S T (1999). "Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (53): 37538–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. PMID 10608806.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Goudelock, Dawn Marie (2003). "Regulatory interactions between the checkpoint kinase Chk1 and the proteins of the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (32): 29940–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301765200. PMID 12756247.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yavuzer, U (1998). "DNA end-independent activation of DNA-PK mediated via association with the DNA-binding protein C1D". Genes Dev. 12 (14): 2188–99. doi:10.1101/gad.12.14.2188. PMC 317006. PMID 9679063.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stelzl, Ulrich (2005). "A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome". Cell. 122 (6): 957–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. PMID 16169070.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Yan, Chunhong (2002). "ATF3 represses 72-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2) expression by antagonizing p53-dependent trans-activation of the collagenase promoter". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (13): 10804–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112069200. PMID 11792711.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hofmann, Thomas G (2002). "Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2". Nat. Cell Biol. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/ncb715. PMID 11740489.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kim, Eun-Joo (2002). "Identification and characterization of HIPK2 interacting with p73 and modulating functions of the p53 family in vivo". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (35): 32020–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200153200. PMID 11925430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chen, Delin (2003). "Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (16): 13595–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200694200. PMID 12606552.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ravi, R (2000). "Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Genes Dev. 14 (1): 34–44. PMC 316350. PMID 10640274.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hansson, Lars O (2002). "Two sequence motifs from HIF-1alpha bind to the DNA-binding site of p53". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (16): 10305–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.122347199. PMC 124909. PMID 12124396.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ An, W G (1998). "Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha". Nature. 392 (6674): 405–8. doi:10.1038/32925. PMID 9537326.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frade, R (2000). "RB18A, whose gene is localized on chromosome 17q12-q21.1, regulates in vivo p53 transactivating activity". Cancer Res. 60 (23): 6585–9. PMID 11118038.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Drané, P (1997). "Identification of RB18A, a 205 kDa new p53 regulatory protein which shares antigenic and functional properties with p53". Oncogene. 15 (25): 3013–24. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201492. PMID 9444950.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Liu, J (2001). "Physical interaction between p53 and primary response gene Egr-1". Int. J. Oncol. 18 (4): 863–70. PMID 11251186.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Peng, Y C (2001). "AMF1 (GPS2) modulates p53 transactivation". Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 (17): 5913–24. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.17.5913-5924.2001. PMC 87310. PMID 11486030.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Gallagher, W M (1999). "MBP1: a novel mutant p53-specific protein partner with oncogenic properties". Oncogene. 18 (24): 3608–16. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202937. PMID 10380882.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kurki, Sari (2003). "Cellular stress and DNA damage invoke temporally distinct Mdm2, p53 and PML complexes and damage-specific nuclear relocalization". J. Cell. Sci. 116 (Pt 19): 3917–25. doi:10.1242/jcs.00714. PMID 12915590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fogal, V (2000). "Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform". EMBO J. 19 (22): 6185–95. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.22.6185. PMC 305840. PMID 11080164.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Guo, A (2000). "The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis". Nat. Cell Biol. 2 (10): 730–6. doi:10.1038/35036365. PMID 11025664.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Xie, S (2001). "Plk3 functionally links DNA damage to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis at least in part via the p53 pathway". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (46): 43305–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106050200. PMID 11551930.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bahassi, El Mustapha (2002). "Mammalian Polo-like kinase 3 (Plk3) is a multifunctional protein involved in stress response pathways". Oncogene. 21 (43): 6633–40. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205850. PMID 12242661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tomasini, Richard (2003). "TP53INP1s and homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 (HIPK2) are partners in regulating p53 activity". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (39): 37722–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301979200. PMID 12851404.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Okamura, S (2001). "p53DINP1, a p53-inducible gene, regulates p53-dependent apoptosis". Mol. Cell. 8 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00284-2. PMID 11511362.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chen, Shih-Shun (2002). "Suppression of the STK15 oncogenic activity requires a transactivation-independent p53 function". EMBO J. 21 (17): 4491–9. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf409. PMC 126178. PMID 12198151.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Dong, Yuanshu (2003). "Regulation of BRCC, a holoenzyme complex containing BRCA1 and BRCA2, by a signalosome-like subunit and its role in DNA repair". Mol. Cell. 12 (5): 1087–99. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00424-6. PMID 14636569.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernal, Juan A (2002). "Human securin interacts with p53 and modulates p53-mediated transcriptional activity and apoptosis". Nat. Genet. 32 (2): 306–11. doi:10.1038/ng997. PMID 12355087.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Tian, Hui (2002). "Radiation-induced phosphorylation of Chk1 at S345 is associated with p53-dependent cell cycle arrest pathways". Neoplasia. 4 (2): 171–80. doi:10.1038/sj/neo/7900219. PMC 1550321. PMID 11896572.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Sengupta, Sagar (2004). "Functional interaction between BLM helicase and 53BP1 in a Chk1-mediated pathway during S-phase arrest". J. Cell Biol. 166 (6): 801–13. doi:10.1083/jcb.200405128. PMC 2172115. PMID 15364958.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zhao, Lili (2003). "Cyclin G1 has growth inhibitory activity linked to the ARF-Mdm2-p53 and pRb tumor suppressor pathways". Mol. Cancer Res. 1 (3): 195–206. PMID 12556559.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Schneider, E (1998). "Regulation of CAK kinase activity by p53". Oncogene. 17 (21): 2733–41. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202504. PMID 9840937.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gobert, C (1999). "The interaction between p53 and DNA topoisomerase I is regulated differently in cells with wild-type and mutant p53". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (18): 10355–60. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10355. PMC 17892. PMID 10468612.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mao, Yinghui (2002). "Subnuclear distribution of topoisomerase I is linked to ongoing transcription and p53 status". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (3): 1235–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.022631899. PMC 122173. PMID 11805286.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kahyo, T (2001). "Involvement of PIAS1 in the sumoylation of tumor suppressor p53". Mol. Cell. 8 (3): 713–8. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00349-5. PMID 11583632.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Li, L (2000). "The human Cdc14 phosphatases interact with and dephosphorylate the tumor suppressor protein p53". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (4): 2410–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.4.2410. PMID 10644693.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Marmorstein, L Y (1998). "The BRCA2 gene product functionally interacts with p53 and RAD51". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (23): 13869–74. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13869. PMC 24938. PMID 9811893.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abramovitch, S (2003). "Functional and physical interactions between BRCA1 and p53 in transcriptional regulation of the IGF-IR gene". Horm. Metab. Res. 35 (11–12): 758–62. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814154. PMID 14710355.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ouchi, T (1998). "BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (5): 2302–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. PMC 19327. PMID 9482880.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chai, Y L (1999). "The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter". Oncogene. 18 (1): 263–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202323. PMID 9926942.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zhang, H (1998). "BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity". Oncogene. 16 (13): 1713–21. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201932. PMID 9582019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leng, Roger P (2003). "Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation". Cell. 112 (6): 779–91. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00193-4. PMID 12654245.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sheng, Yi (2008). "Molecular basis of Pirh2-mediated p53 ubiquitylation". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15 (12): 1334–42. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1521. PMID 19043414.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rizos, Helen (2003). "Association of p14ARF with the p120E4F transcriptional repressor enhances cell cycle inhibition". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (7): 4981–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M210978200. PMID 12446718.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sandy, P (2000). "p53 is involved in the p120E4F-mediated growth arrest". Oncogene. 19 (2): 188–99. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203250. PMID 10644996.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Gueven, Nuri (2004). "Aprataxin, a novel protein that protects against genotoxic stress". Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 (10): 1081–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh122. PMID 15044383.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Malanga, M (1998). "Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains of p53 and alters its DNA binding functions". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (19): 11839–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11839. PMID 9565608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bai, L (2001). "ZBP-89 promotes growth arrest through stabilization of p53". Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 (14): 4670–83. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.14.4670-4683.2001. PMC 87140. PMID 11416144.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Imamura, T (2001). "Interaction with p53 enhances binding of cisplatin-modified DNA by high mobility group 1 protein". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (10): 7534–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008143200. PMID 11106654.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dintilhac, Agnès (2002). "HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (9): 7021–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108417200. PMID 11748221.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Han, Jung Min (2008). "AIMP2/p38, the scaffold for the multi-tRNA synthetase complex, responds to genotoxic stresses via p53". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (32): 11206–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800297105. PMC 2516205. PMID 18695251.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Simons, A (1997). "PACT: cloning and characterization of a cellular p53 binding protein that interacts with Rb". Oncogene. 14 (2): 145–55. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1200825. PMID 9010216.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Derbyshire, Dean J (2002). "Crystal structure of human 53BP1 BRCT domains bound to p53 tumour suppressor". EMBO J. 21 (14): 3863–72. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf383. PMC 126127. PMID 12110597.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ekblad, Caroline M S (2004). "Comparison of BRCT domains of BRCA1 and 53BP1: a biophysical analysis". Protein Sci. 13 (3): 617–25. doi:10.1110/ps.03461404. PMC 2286730. PMID 14978302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lo, Kevin W-H (2005). "The 8-kDa dynein light chain binds to p53-binding protein 1 and mediates DNA damage-induced p53 nuclear accumulation". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (9): 8172–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M411408200. PMID 15611139.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Joo, Woo S (2002). "Structure of the 53BP1 BRCT region bound to p53 and its comparison to the Brca1 BRCT structure". Genes Dev. 16 (5): 583–93. doi:10.1101/gad.959202. PMC 155350. PMID 11877378.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Derbyshire, Dean J (2002). "Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the BRCT domains of human 53BP1 bound to the p53 tumour suppressor". Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58 (Pt 10 Pt 2): 1826–9. doi:10.1107/S0907444902010910. PMID 12351827.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Iwabuchi, K (1994). "Two cellular proteins that bind to wild-type but not mutant p53". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 (13): 6098–102. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.13.6098. PMC 44145. PMID 8016121.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Luciani, M G (2000). "The C-terminal regulatory domain of p53 contains a functional docking site for cyclin A". J. Mol. Biol. 300 (3): 503–18. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3830. PMID 10884347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ababneh, M (2001). "Downregulation of the cdc2/cyclin B protein kinase activity by binding of p53 to p34(cdc2)". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283 (2): 507–12. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.4792. ISSN 0006-291X. PMID 11327730.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Naumovski, L (1996). "The p53-binding protein 53BP2 also interacts with Bc12 and impedes cell cycle progression at G2/M". Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 (7): 3884–92. PMC 231385. PMID 8668206.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Cowell, I G (2000). "Human topoisomerase IIalpha and IIbeta interact with the C-terminal region of p53". Exp. Cell Res. 255 (1): 86–94. doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4772. PMID 10666337.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wang, X W (2001). "Functional interaction of p53 and BLM DNA helicase in apoptosis". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (35): 32948–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103298200. PMID 11399766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Garkavtsev, I V (2001). "The Bloom syndrome protein interacts and cooperates with p53 in regulation of transcription and cell growth control". Oncogene. 20 (57): 8276–80. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205120. PMID 11781842.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Yang, Qin (2002). "The processing of Holliday junctions by BLM and WRN helicases is regulated by p53". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (35): 31980–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204111200. PMID 12080066.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Leu, J I-Ju (2004). "Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex". Nat. Cell Biol. 6 (5): 443–50. doi:10.1038/ncb1123. PMID 15077116.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Nikolaev, Anatoly Y (2003). "Parc: a cytoplasmic anchor for p53". Cell. 112 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01255-2. PMID 12526791.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Stürzbecher, H W (1996). "p53 is linked directly to homologous recombination processes via RAD51/RecA protein interaction". EMBO J. 15 (8): 1992–2002. PMC 450118. PMID 8617246.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Buchhop, S (1997). "Interaction of p53 with the human Rad51 protein". Nucleic Acids Res. 25 (19): 3868–74. doi:10.1093/nar/25.19.3868. PMC 146972. PMID 9380510.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Zhang, Zhuo (2008). "Proteasome activator PA28 gamma regulates p53 by enhancing its MDM2-mediated degradation". EMBO J. 27 (6): 852–64. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.25. PMC 2265109. PMID 18309296.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lin, Jing (2004). "Inhibiting S100B restores p53 levels in primary malignant melanoma cancer cells". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (32): 34071–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405419200. PMID 15178678.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Minty, A (2000). "Covalent modification of p73alpha by SUMO-1. Two-hybrid screening with p73 identifies novel SUMO-1-interacting proteins and a SUMO-1 interaction motif". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (46): 36316–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004293200. PMID 10961991.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Shen, Z (1996). "Associations of UBE2I with RAD52, UBL1, p53, and RAD51 proteins in a yeast two-hybrid system". Genomics. 37 (2): 183–6. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0540. PMID 8921390.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernier-Villamor, Victor (2002). "Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1". Cell. 108 (3): 345–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00630-X. PMID 11853669.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wulf, Gerburg M (2002). "Role of Pin1 in the regulation of p53 stability and p21 transactivation, and cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (50): 47976–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200538200. PMID 12388558.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zacchi, Paola (2002). "The prolyl isomerase Pin1 reveals a mechanism to control p53 functions after genotoxic insults". Nature. 419 (6909): 853–7. doi:10.1038/nature01120. PMID 12397362.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ivanchuk, Stacey M (2008). "p14ARF interacts with DAXX: effects on HDM2 and p53". Cell Cycle. 7 (12): 1836–50. PMID 18583933.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Steffan, J S (2000). "The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (12): 6763–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.100110097. PMC 18731. PMID 10823891.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ a b Freeman, Daniel J (2003). "PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms". Cancer Cell. 3 (2): 117–30. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00021-7. PMID 12620407.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ a b Akakura, S (2001). "A role for Hsc70 in regulating nucleocytoplasmic transport of a temperature-sensitive p53 (p53Val-135)". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (18): 14649–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100200200. PMID 11297531.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Ko, L J (1997). "p53 is phosphorylated by CDK7-cyclin H in a p36MAT1-dependent manner". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (12): 7220–9. PMC 232579. PMID 9372954.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Shiseki, Masayuki (2003). "p29ING4 and p28ING5 bind to p53 and p300, and enhance p53 activity". Cancer Res. 63 (10): 2373–8. PMID 12750254.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shinobu, N (1999). "Physical interaction and functional antagonism between the RNA polymerase II elongation factor ELL and p53". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (24): 17003–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.24.17003. PMID 10358050.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lim, Ssang-Taek (2008). "Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation". Mol. Cell. 29 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. PMC 2234035. PMID 18206965.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Colaluca, Ivan N (2008). "NUMB controls p53 tumour suppressor activity". Nature. 451 (7174): 76–80. doi:10.1038/nature06412. PMID 18172499.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Leung, Ka Man (2002). "The candidate tumor suppressor ING1b can stabilize p53 by disrupting the regulation of p53 by MDM2". Cancer Res. 62 (17): 4890–3. PMID 12208736.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Garkavtsev, I (1998). "The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control". Nature. 391 (6664): 295–8. doi:10.1038/34675. PMID 9440695.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zhang, Y (1998). "ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways". Cell. 92 (6): 725–34. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81401-4. PMID 9529249.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Li, Muyang (2002). "Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization". Nature. 416 (6881): 648–53. doi:10.1038/nature737. PMID 11923872.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Tsai, Kuo-Wang (2008). "Two wobble-splicing events affect ING4 protein subnuclear localization and degradation". Exp. Cell Res. 314 (17): 3130–41. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.002. PMID 18775696.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Waterman, M J (1998). "ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins". Nat. Genet. 19 (2): 175–8. doi:10.1038/542. PMID 9620776.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lyakhovich, Alex (2003). "Supramolecular complex formation between Rad6 and proteins of the p53 pathway during DNA damage-induced response". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (7): 2463–75. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.7.2463-2475.2003. PMC 150718. PMID 12640129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sehat, Bita (2008). "Identification of c-Cbl as a new ligase for insulin-like growth factor-I receptor with distinct roles from Mdm2 in receptor ubiquitination and endocytosis". Cancer Res. 68 (14): 5669–77. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6364. PMID 18632619.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Song, Min Sup (2008). "The tumour suppressor RASSF1A promotes MDM2 self-ubiquitination by disrupting the MDM2-DAXX-HAUSP complex". EMBO J. 27 (13): 1863–74. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.115. PMC 2486425. PMID 18566590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yang, Wensheng (2008). "CARPs enhance p53 turnover by degrading 14-3-3sigma and stabilizing MDM2". Cell Cycle. 7 (5): 670–82. doi:10.4161/cc.7.5.5701. PMID 18382127.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abe, Yoshinori (2008). "Hedgehog signaling overrides p53-mediated tumor suppression by activating Mdm2". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (12): 4838–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712216105. PMC 2290789. PMID 18359851.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dohmesen, Christoph (2008). "Specific inhibition of Mdm2-mediated neddylation by Tip60". Cell Cycle. 7 (2): 222–31. doi:10.4161/cc.7.2.5185. PMID 18264029.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brosh, R M (2001). "p53 Modulates the exonuclease activity of Werner syndrome protein". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (37): 35093–102. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103332200. PMID 11427532.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tsai, Robert Y L (2002). "A nucleolar mechanism controlling cell proliferation in stem cells and cancer cells". Genes Dev. 16 (23): 2991–3003. doi:10.1101/gad.55671. PMC 187487. PMID 12464630.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Uramoto, Hidetaka (2003). "Physical interaction of tumour suppressor p53/p73 with CCAAT-binding transcription factor 2 (CTF2) and differential regulation of human high-mobility group 1 (HMG1) gene expression". Biochem. J. 371 (Pt 2): 301–10. doi:10.1042/BJ20021646. PMC 1223307. PMID 12534345.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chang, N S (2001). "Hyaluronidase induction of a WW domain-containing oxidoreductase that enhances tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (5): 3361–70. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007140200. PMID 11058590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Kojic, Snezana (2004). "The Ankrd2 protein, a link between the sarcomere and the nucleus in skeletal muscle". J. Mol. Biol. 339 (2): 313–25. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.071. PMID 15136035.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Okamoto, T (2000). "Direct interaction of p53 with the Y-box binding protein, YB-1: a mechanism for regulation of human gene expression". Oncogene. 19 (54): 6194–202. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204029. PMID 11175333.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chang, Nan-Shan (2002). "The non-ankyrin C terminus of Ikappa Balpha physically interacts with p53 in vivo and dissociates in response to apoptotic stress, hypoxia, DNA damage, and transforming growth factor-beta 1-mediated growth suppression". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (12): 10323–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106607200. PMID 11799106.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Seto, E (1992). "Wild-type p53 binds to the TATA-binding protein and represses transcription". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (24): 12028–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.24.12028. PMC 50691. PMID 1465435.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cvekl, A (1999). "Pax-6 interactions with TATA-box-binding protein and retinoblastoma protein". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40 (7): 1343–50. PMID 10359315.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wadhwa, Renu (2002). "Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein". Exp. Cell Res. 274 (2): 246–53. doi:10.1006/excr.2002.5468. PMID 11900485.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Badciong, James C (2002). "MdmX is a RING finger ubiquitin ligase capable of synergistically enhancing Mdm2 ubiquitination". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (51): 49668–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208593200. PMID 12393902.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Shvarts, A (1997). "Isolation and identification of the human homolog of a new p53-binding protein, Mdmx". Genomics. 43 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4775. PMID 9226370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Li, Muyang (2003). "Mono- versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2". Science. 302 (5652): 1972–5. doi:10.1126/science.1091362. PMID 14671306.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Latonen, L (2001). "UV-radiation induces dose-dependent regulation of p53 response and modulates p53-HDM2 interaction in human fibroblasts". Oncogene. 20 (46): 6784–93. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204883. PMID 11709713.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Grossman, S R (1998). "p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation". Mol. Cell. 2 (4): 405–15. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80140-9. PMID 9809062.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fang, S (2000). "Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (12): 8945–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.12.8945. PMID 10722742.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Liu, G (2000). "Estrogen receptor protects p53 from deactivation by human double minute-2". Cancer Res. 60 (7): 1810–4. PMID 10766163.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Buschmann, T (2000). "SUMO-1 modification of Mdm2 prevents its self-ubiquitination and increases Mdm2 ability to ubiquitinate p53". Cell. 101 (7): 753–62. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80887-9. PMID 10892746.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Chen, J (1993). "Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains". Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 (7): 4107–14. PMC 359960. PMID 7686617.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thut, C J (1997). "Repression of p53-mediated transcription by MDM2: a dual mechanism". Genes Dev. 11 (15): 1974–86. doi:10.1101/gad.11.15.1974. PMC 316412. PMID 9271120.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wawrzynow, Bartosz (2009). "A function for the RING finger domain in the allosteric control of MDM2 conformation and activity". J. Biol. Chem. 284 (17): 11517–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.M809294200. PMC 2670157. PMID 19188367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ochocka, Anna Maria (2009). "FKBP25, a novel regulator of the p53 pathway, induces the degradation of MDM2 and activation of p53". FEBS Lett. 583 (4): 621–6. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.009. PMID 19166840.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chen, Deng (2009). "RYBP stabilizes p53 by modulating MDM2". EMBO Rep. 10 (2): 166–72. doi:10.1038/embor.2008.231. PMC 2637313. PMID 19098711.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hedström, Elisabeth (2009). "Tumor-specific induction of apoptosis by a p53-reactivating compound". Exp. Cell Res. 315 (3): 451–61. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.009. PMID 19071110.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brenkman, Arjan B (2008). "Mdm2 induces mono-ubiquitination of FOXO4". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): e2819. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002819. PMC 2475507. PMID 18665269.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Qiu, W (2008). "Retinoblastoma protein modulates gankyrin-MDM2 in regulation of p53 stability and chemosensitivity in cancer cells". Oncogene. 27 (29): 4034–43. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.43. PMID 18332869.