Estrogen receptor beta

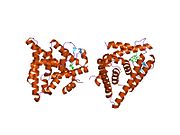

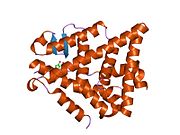

Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) also known as NR3A2 (nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group A, member 2) is one of two main types of estrogen receptor—a nuclear receptor which is activated by the sex hormone estrogen.[5] In humans ERβ is encoded by the ESR2 gene.[6]

Function

[edit]ERβ is a member of the family of estrogen receptors and the superfamily of nuclear receptor transcription factors. The gene product contains an N-terminal DNA binding domain and C-terminal ligand binding domain and is localized to the nucleus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria. Upon binding to 17-β-estradiol, estriol or related ligands, the encoded protein forms homo-dimers or hetero-dimers with estrogen receptor α that interact with specific DNA sequences to activate transcription. Some isoforms dominantly inhibit the activity of other estrogen receptor family members. Several alternatively spliced transcript variants of this gene have been described, but the full-length nature of some of these variants has not been fully characterized.[7]

ERβ may inhibit cell proliferation and opposes the actions of ERα in reproductive tissue.[8] ERβ may also have an important role in adaptive function of the lung during pregnancy.[9]

ERβ is a potent tumor suppressor and plays a crucial role in many cancer types such as prostate cancer and ovarian cancer.[10][11]

Mammary gland

[edit]ERβ knockout mice show normal mammary gland development at puberty and are able to lactate normally.[12][13][14] The mammary glands of adult virgin female mice are indistinguishable from those of age-matched wild-type virgin female mice.[12] This is in contrast to ERα knockout mice, in which a complete absence of mammary gland development at puberty and thereafter is observed.[12][14] Administration of the selective ERβ agonist ERB-041 to immature ovariectomized female rats produced no observable effects in the mammary glands, further indicating that the ERβ is non-mammotrophic.[15][14][16]

Although ERβ is not required for pubertal development of the mammary glands, it may be involved in terminal differentiation in pregnancy, and may also be necessary to maintain the organization and differentiation of mammary epithelium in adulthood.[17][18] In old female ERβ knockout mice, severe cystic mammary disease that is similar in appearance to postmenopausal mastopathy develops, whereas this does not occur in aged wild-type female mice.[13] However, ERβ knockout mice are not only deficient in ERβ signaling in the mammary glands, but also have deficient progesterone exposure due to impairment of corpora lutea formation.[13][17] This complicates attribution of the preceding findings to mammary ERβ signaling.[13][17]

Selective ERβ agonism with diarylpropionitrile (DPN) has been found to counteract the proliferative effects in the mammary glands of selective ERα agonism with propylpyrazoletriol (PPT) in ovariectomized postmenopausal female rats.[19][20] Similarly, overexpression of ERβ via lentiviral infection in mature virgin female rats decreases mammary proliferation.[20] ERα signaling has proliferative effects in both normal breast and breast cancer cell lines, whereas ERβ has generally antiproliferative effects in such cell lines.[17] However, ERβ has been found to have proliferative effects in some breast cell lines.[17]

Expression of ERα and ERβ in the mammary gland have been found to vary throughout the menstrual cycle and in an ovariectomized state in female rats.[20] Whereas mammary ERα in rhesus macaques is downregulated in response to increased estradiol levels, expression of ERβ in the mammary glands is not.[21] Expression of ERα and ERβ in the mammary glands also differs throughout life in female mice.[22] Mammary ERα expression is higher and mammary ERβ expression lower in younger female mice, while mammary ERα expression is lower and mammary ERβ expression higher in older female mice as well as in parous female mice.[22] Mammary proliferation and estrogen sensitivity is higher in young female mice than in old or parous female mice, particularly during pubertal mammary gland development.[22]

Tissue distribution

[edit]ERβ is expressed by many tissues including the uterus,[23] blood monocytes and tissue macrophages, colonic and pulmonary epithelial cells and in prostatic epithelium and in malignant counterparts of these tissues. Also, ERβ is found throughout the brain at different concentrations in different neuron clusters.[24][25] ERβ is also highly expressed in normal breast epithelium, although its expression declines with cancer progression.[26] ERβ is expressed in all subtypes of breast cancer.[27] Controversy regarding ERβ protein expression has hindered study of ERβ, but highly sensitive monoclonal antibodies have been produced and well-validated to address these issues.[28]

ERβ abnormalities

[edit]ERβ function is related to various cardiovascular targets including ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA-1). Polymorphism may affect ERβ function and lead to altered responses in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy.[29] Abnormalities in gene expression associated with ERβ have also been linked to autism spectrum disorder.[30]

Disease

[edit]Cardiovascular disease

[edit]Mutations in ERβ have been shown to influence cardiomyocytes, the cells that comprise the largest part of the heart, and can lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). There is a disparity in prevalence of CVD between pre- and post-menopausal women, and the difference can be attributed to estrogen levels. Many types of ERβ receptors exist in order to help regulate gene expression and subsequent health in the body, but binding of 17βE2 (a naturally occurring estrogen) specifically improves cardiac metabolism. The heart utilizes a lot of energy in the form of ATP to properly pump blood and maintain physiological requirements in order to live, and 17βE2 helps by increasing these myocardial ATP levels and respiratory function.[31]

In addition, 17βE2 can alter myocardial signaling pathways and stimulate myocyte regeneration, which can aid in inhibiting myocyte cell death. The ERβ signaling pathway plays a role in both vasodilation and arterial dilation, which contributes to an individual having a healthy heart rate and a decrease in blood pressure. This regulation can increase endothelial function and arterial perfusion, both of which are important to myocyte health. Thus, alterations in this signaling pathways due to ERβ mutation could lead to myocyte cell death from physiological stress. While ERα has a more profound role in regeneration after myocyte cell death, ERβ can still help by increasing endothelial progenitor cell activation and subsequent cardiac function.[32]

Alzheimer's disease

[edit]Genetic variation in ERβ is both sex and age dependent and ERβ polymorphism can lead to accelerated brain aging, cognitive impairment, and development of AD pathology. Similar to CVD, post-menopausal women have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD) due to a loss of estrogen, which affects proper aging of the hippocampus, neural survival and regeneration, and amyloid metabolism. ERβ mRNA is highly expressed in hippocampal formation, an area of the brain that is associated with memory. This expression contributes to increased neuronal survival and helps protect against neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. The pathology of AD is also associated with accumulation of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ). While a proper concentration of Aβ in the brain is important for healthy functioning, too much can lead to cognitive impairment. Thus, ERβ helps control Aβ levels by maintaining the protein it is derived from, β-amyloid precursor protein. ERβ helps by up-regulating insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), which leads to β-amyloid degradation when accumulation levels begin to rise. However, in AD, lack of ERβ causes a decrease in this degradation and an increase in plaque build-up.[33]

ERβ also plays a role in regulating APOE, a risk factor for AD that redistributes lipids across cells. APOE expression in the hippocampus is specifically regulated by 17βE2, affecting learning and memory in individuals afflicted with AD. Thus, estrogen therapy via an ERβ-targeted approach can be used as a prevention method for AD either before or at the onset of menopause. Interactions between ERα and ERβ can lead to antagonistic actions in the brain, so an ERβ-targeted approach can increase therapeutic neural responses independently of ERα. Therapeutically, ERβ can be used in both men and women in order to regulate plaque formation in the brain.[34]

Neuroprotective benefits

[edit]Synaptic strength and plasticity

[edit]ERβ levels can dictate both synaptic strength and neuroplasticity through neural structure modifications. Variations in endogenous estrogen levels cause changes in dendritic architecture in the hippocampus, which affects neural signaling and plasticity. Specifically, lower estrogen levels lead to decreased dendritic spines and improper signaling, inhibiting plasticity of the brain. However, treatment of 17βE2 can reverse this affect, giving it the ability to modify hippocampal structure. As a result of the relationship between dendritic architecture and long-term potentiation (LTP), ERβ can enhance LTP and lead to an increase in synaptic strength. Furthermore, 17βE2 promotes neurogenesis in developing hippocampal neurons and neurons in the subventricular zone and dentate gyrus of the adult human brain. Specifically, ERβ increases the proliferation of progenitor cells to create new neurons and can be increased later in life through 17βE2 treatment.[35][36]

Ligands

[edit]Agonists

[edit]Non-selective

[edit]- Endogenous estrogens (e.g., estradiol, estrone, estriol, estetrol)

- Natural estrogens (e.g., conjugated estrogens)

- Synthetic estrogens (e.g., ethinylestradiol, diethylstilbestrol)

Selective

[edit]Agonists of ERβ selective over ERα include:

- 20-Hydroxyecdysone (ecdysterone, 20-HE, 20-E) — phytoecdysteroid[37]

- 3β-Androstanediol (3β-diol) – endogenous

- 8β-VE2

- AC-186

- Apigenin – phytoestrogen[38]

- Daidzein – phytoestrogen[38]

- DCW234

- Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) – endogenous

- Diarylpropionitrile (DPN)

- ERB-79 and its active enantiomer ERB-26

- ERB-196 (WAY-202196)

- Erteberel (SERBA-1, LY-500307)

- FERb 033 – 62-fold selectivity for ERβ over ERα[39]

- Genistein – phytoestrogen; 16-fold selectivity for ERβ over ERα[38]

- Liquiritigenin (Menerba) – phytoestrogen[38]

- Penduletin – phytoestrogen[38]

- Prinaberel (ERB-041, WAY-202041)

- S-Equol ((S)-4',7-isoflavandiol) – phytoestrogen; 13-fold selectivity for ERβ over ERα[38]

- WAY-166818

- WAY-200070

- WAY-214156

Antagonists

[edit]Non-selective

[edit]- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g., tamoxifen, raloxifene)[40]

- Antiestrogens (e.g., fulvestrant, ICI-164384)

Selective

[edit]Antagonists of ERβ selective over ERα include:

- PHTPP

- (R,R)-Tetrahydrochrysene ((R,R)-THC) – actually not selective over ERα, but rather an agonist instead of antagonist of ERα

Affinities

[edit]| Ligand | Other names | Relative binding affinities (RBA, %)a | Absolute binding affinities (Ki, nM)a | Action | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | ERβ | ERα | ERβ | |||

| Estradiol | E2; 17β-Estradiol | 100 | 100 | 0.115 (0.04–0.24) | 0.15 (0.10–2.08) | Estrogen |

| Estrone | E1; 17-Ketoestradiol | 16.39 (0.7–60) | 6.5 (1.36–52) | 0.445 (0.3–1.01) | 1.75 (0.35–9.24) | Estrogen |

| Estriol | E3; 16α-OH-17β-E2 | 12.65 (4.03–56) | 26 (14.0–44.6) | 0.45 (0.35–1.4) | 0.7 (0.63–0.7) | Estrogen |

| Estetrol | E4; 15α,16α-Di-OH-17β-E2 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 19 | Estrogen |

| Alfatradiol | 17α-Estradiol | 20.5 (7–80.1) | 8.195 (2–42) | 0.2–0.52 | 0.43–1.2 | Metabolite |

| 16-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17β-estradiol | 7.795 (4.94–63) | 50 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 17-Epiestriol | 16α-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 55.45 (29–103) | 79–80 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16,17-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 1.0 | 13 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestradiol | 2-OH-E2 | 22 (7–81) | 11–35 | 2.5 | 1.3 | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestradiol | 2-MeO-E2 | 0.0027–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestradiol | 4-OH-E2 | 13 (8–70) | 7–56 | 1.0 | 1.9 | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestradiol | 4-MeO-E2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestrone | 2-OH-E1 | 2.0–4.0 | 0.2–0.4 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestrone | 2-MeO-E1 | <0.001–<1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestrone | 4-OH-E1 | 1.0–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestrone | 4-MeO-E1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16α-Hydroxyestrone | 16α-OH-E1; 17-Ketoestriol | 2.0–6.5 | 35 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestriol | 2-OH-E3 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestriol | 4-MeO-E3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol sulfate | E2S; Estradiol 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol disulfate | Estradiol 3,17β-disulfate | 0.0004 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-glucuronide | E2-3G | 0.0079 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 17β-glucuronide | E2-17G | 0.0015 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-gluc. 17β-sulfate | E2-3G-17S | 0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estrone sulfate | E1S; Estrone 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | >10 | >10 | Metabolite |

| Estradiol benzoate | EB; Estradiol 3-benzoate | 10 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estradiol 17β-benzoate | E2-17B | 11.3 | 32.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estrone methyl ether | Estrone 3-methyl ether | 0.145 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| ent-Estradiol | 1-Estradiol | 1.31–12.34 | 9.44–80.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Equilin | 7-Dehydroestrone | 13 (4.0–28.9) | 13.0–49 | 0.79 | 0.36 | Estrogen |

| Equilenin | 6,8-Didehydroestrone | 2.0–15 | 7.0–20 | 0.64 | 0.62 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 7.9–113 | 7.9–108 | 0.09 | 0.17 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17α-estradiol | 18.6 (18–41) | 14–32 | 0.24 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17β-estradiol | 35–68 | 90–100 | 0.15 | 0.20 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17α-estradiol | 20 | 49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estradiol | 8,9-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 68 | 72 | 0.15 | 0.25 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estrone | 8,9-Dehydroestrone | 19 | 32 | 0.52 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| Ethinylestradiol | EE; 17α-Ethynyl-17β-E2 | 120.9 (68.8–480) | 44.4 (2.0–144) | 0.02–0.05 | 0.29–0.81 | Estrogen |

| Mestranol | EE 3-methyl ether | ? | 2.5 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Moxestrol | RU-2858; 11β-Methoxy-EE | 35–43 | 5–20 | 0.5 | 2.6 | Estrogen |

| Methylestradiol | 17α-Methyl-17β-estradiol | 70 | 44 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Diethylstilbestrol | DES; Stilbestrol | 129.5 (89.1–468) | 219.63 (61.2–295) | 0.04 | 0.05 | Estrogen |

| Hexestrol | Dihydrodiethylstilbestrol | 153.6 (31–302) | 60–234 | 0.06 | 0.06 | Estrogen |

| Dienestrol | Dehydrostilbestrol | 37 (20.4–223) | 56–404 | 0.05 | 0.03 | Estrogen |

| Benzestrol (B2) | – | 114 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Chlorotrianisene | TACE | 1.74 | ? | 15.30 | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylethylene | TPE | 0.074 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylbromoethylene | TPBE | 2.69 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Tamoxifen | ICI-46,474 | 3 (0.1–47) | 3.33 (0.28–6) | 3.4–9.69 | 2.5 | SERM |

| Afimoxifene | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen; 4-OHT | 100.1 (1.7–257) | 10 (0.98–339) | 2.3 (0.1–3.61) | 0.04–4.8 | SERM |

| Toremifene | 4-Chlorotamoxifen; 4-CT | ? | ? | 7.14–20.3 | 15.4 | SERM |

| Clomifene | MRL-41 | 25 (19.2–37.2) | 12 | 0.9 | 1.2 | SERM |

| Cyclofenil | F-6066; Sexovid | 151–152 | 243 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Nafoxidine | U-11,000A | 30.9–44 | 16 | 0.3 | 0.8 | SERM |

| Raloxifene | – | 41.2 (7.8–69) | 5.34 (0.54–16) | 0.188–0.52 | 20.2 | SERM |

| Arzoxifene | LY-353,381 | ? | ? | 0.179 | ? | SERM |

| Lasofoxifene | CP-336,156 | 10.2–166 | 19.0 | 0.229 | ? | SERM |

| Ormeloxifene | Centchroman | ? | ? | 0.313 | ? | SERM |

| Levormeloxifene | 6720-CDRI; NNC-460,020 | 1.55 | 1.88 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Ospemifene | Deaminohydroxytoremifene | 0.82–2.63 | 0.59–1.22 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Bazedoxifene | – | ? | ? | 0.053 | ? | SERM |

| Etacstil | GW-5638 | 4.30 | 11.5 | ? | ? | SERM |

| ICI-164,384 | – | 63.5 (3.70–97.7) | 166 | 0.2 | 0.08 | Antiestrogen |

| Fulvestrant | ICI-182,780 | 43.5 (9.4–325) | 21.65 (2.05–40.5) | 0.42 | 1.3 | Antiestrogen |

| Propylpyrazoletriol | PPT | 49 (10.0–89.1) | 0.12 | 0.40 | 92.8 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-LE2 | 16α-Lactone-17β-estradiol | 14.6–57 | 0.089 | 0.27 | 131 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-Iodo-E2 | 16α-Iodo-17β-estradiol | 30.2 | 2.30 | ? | ? | ERα agonist |

| Methylpiperidinopyrazole | MPP | 11 | 0.05 | ? | ? | ERα antagonist |

| Diarylpropionitrile | DPN | 0.12–0.25 | 6.6–18 | 32.4 | 1.7 | ERβ agonist |

| 8β-VE2 | 8β-Vinyl-17β-estradiol | 0.35 | 22.0–83 | 12.9 | 0.50 | ERβ agonist |

| Prinaberel | ERB-041; WAY-202,041 | 0.27 | 67–72 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| ERB-196 | WAY-202,196 | ? | 180 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| Erteberel | SERBA-1; LY-500,307 | ? | ? | 2.68 | 0.19 | ERβ agonist |

| SERBA-2 | – | ? | ? | 14.5 | 1.54 | ERβ agonist |

| Coumestrol | – | 9.225 (0.0117–94) | 64.125 (0.41–185) | 0.14–80.0 | 0.07–27.0 | Xenoestrogen |

| Genistein | – | 0.445 (0.0012–16) | 33.42 (0.86–87) | 2.6–126 | 0.3–12.8 | Xenoestrogen |

| Equol | – | 0.2–0.287 | 0.85 (0.10–2.85) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Daidzein | – | 0.07 (0.0018–9.3) | 0.7865 (0.04–17.1) | 2.0 | 85.3 | Xenoestrogen |

| Biochanin A | – | 0.04 (0.022–0.15) | 0.6225 (0.010–1.2) | 174 | 8.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Kaempferol | – | 0.07 (0.029–0.10) | 2.2 (0.002–3.00) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Naringenin | – | 0.0054 (<0.001–0.01) | 0.15 (0.11–0.33) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| 8-Prenylnaringenin | 8-PN | 4.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Quercetin | – | <0.001–0.01 | 0.002–0.040 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Ipriflavone | – | <0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Miroestrol | – | 0.39 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Deoxymiroestrol | – | 2.0 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Sitosterol | – | <0.001–0.0875 | <0.001–0.016 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Resveratrol | – | <0.001–0.0032 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| α-Zearalenol | – | 48 (13–52.5) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Zearalenol | – | 0.6 (0.032–13) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zeranol | α-Zearalanol | 48–111 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Taleranol | β-Zearalanol | 16 (13–17.8) | 14 | 0.8 | 0.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalenone | ZEN | 7.68 (2.04–28) | 9.45 (2.43–31.5) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalanone | ZAN | 0.51 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Bisphenol A | BPA | 0.0315 (0.008–1.0) | 0.135 (0.002–4.23) | 195 | 35 | Xenoestrogen |

| Endosulfan | EDS | <0.001–<0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Kepone | Chlordecone | 0.0069–0.2 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| o,p'-DDT | – | 0.0073–0.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| p,p'-DDT | – | 0.03 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Methoxychlor | p,p'-Dimethoxy-DDT | 0.01 (<0.001–0.02) | 0.01–0.13 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| HPTE | Hydroxychlor; p,p'-OH-DDT | 1.2–1.7 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Testosterone | T; 4-Androstenolone | <0.0001–<0.01 | <0.002–0.040 | >5000 | >5000 | Androgen |

| Dihydrotestosterone | DHT; 5α-Androstanolone | 0.01 (<0.001–0.05) | 0.0059–0.17 | 221–>5000 | 73–1688 | Androgen |

| Nandrolone | 19-Nortestosterone; 19-NT | 0.01 | 0.23 | 765 | 53 | Androgen |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone | DHEA; Prasterone | 0.038 (<0.001–0.04) | 0.019–0.07 | 245–1053 | 163–515 | Androgen |

| 5-Androstenediol | A5; Androstenediol | 6 | 17 | 3.6 | 0.9 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenediol | – | 0.5 | 0.6 | 23 | 19 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenedione | A4; Androstenedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| 3α-Androstanediol | 3α-Adiol | 0.07 | 0.3 | 260 | 48 | Androgen |

| 3β-Androstanediol | 3β-Adiol | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | Androgen |

| Androstanedione | 5α-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Etiocholanedione | 5β-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Methyltestosterone | 17α-Methyltestosterone | <0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Androgen |

| Ethinyl-3α-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3α-adiol | 4.0 | <0.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Ethinyl-3β-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3β-adiol | 50 | 5.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Progesterone | P4; 4-Pregnenedione | <0.001–0.6 | <0.001–0.010 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Norethisterone | NET; 17α-Ethynyl-19-NT | 0.085 (0.0015–<0.1) | 0.1 (0.01–0.3) | 152 | 1084 | Progestogen |

| Norethynodrel | 5(10)-Norethisterone | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | <0.1–0.22 | 14 | 53 | Progestogen |

| Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethynodrel | 0.5 (0.45–2.0) | 0.2–0.076 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Δ4-Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethisterone | 0.069–<0.1 | 0.027–<0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | – | 2.5 (1.06–5.0) | 0.6–0.8 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | – | 1.6 (0.75–1.9) | 0.070–0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Footnotes: a = (1) Binding affinity values are of the format "median (range)" (# (#–#)), "range" (#–#), or "value" (#) depending on the values available. The full sets of values within the ranges can be found in the Wiki code. (2) Binding affinities were determined via displacement studies in a variety of in-vitro systems with labeled estradiol and human ERα and ERβ proteins (except the ERβ values from Kuiper et al. (1997), which are rat ERβ). Sources: See template page. | ||||||

Interactions

[edit]Estrogen receptor beta has been shown to interact with:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000140009 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000021055 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA (June 1996). "Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (12): 5925–5930. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. PMC 39164. PMID 8650195.

- ^ Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R (August 1996). "ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor". FEBS Letters. 392 (1): 49–53. Bibcode:1996FEBSL.392...49M. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-X. PMID 8769313. S2CID 85795649.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: ESR2 estrogen receptor 2 (ER beta)".

- ^ Weihua Z, Saji S, Mäkinen S, Cheng G, Jensen EV, Warner M, Gustafsson JA (May 2000). "Estrogen receptor (ER) beta, a modulator of ERalpha in the uterus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (11): 5936–5941. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.5936W. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.11.5936. PMC 18537. PMID 10823946.

- ^ Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, Germolec DR, Korach KS, Zeldin DC (August 2007). "The impact of sex and sex hormones on lung physiology and disease: lessons from animal studies". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 293 (2): L272–L278. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00174.2007. PMID 17575008. S2CID 3175960.

- ^ Stettner M, Kaulfuss S, Burfeind P, Schweyer S, Strauss A, Ringert RH, Thelen P (October 2007). "The relevance of estrogen receptor-beta expression to the antiproliferative effects observed with histone deacetylase inhibitors and phytoestrogens in prostate cancer treatment". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 6 (10): 2626–2633. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0197. PMID 17913855.

- ^ Kyriakidis I, Papaioannidou P (June 2016). "Estrogen receptor beta and ovarian cancer: a key to pathogenesis and response to therapy". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 293 (6): 1161–1168. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4027-8. PMID 26861465. S2CID 25627227.

- ^ a b c Couse JF, Korach KS (June 1999). "Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us?". Endocrine Reviews. 20 (3): 358–417. doi:10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. PMID 10368776.

- ^ a b c d Gustafsson JA, Warner M (November 2000). "Estrogen receptor beta in the breast: role in estrogen responsiveness and development of breast cancer". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 74 (5): 245–248. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00130-8. PMID 11162931. S2CID 39714457.

- ^ a b c Nilsson S, Gustafsson JÅ (2010). "Estrogen Receptors: Their Actions and Functional Roles in Health and Disease". Nuclear Receptors. pp. 91–141. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3303-1_5. ISBN 978-90-481-3302-4.

- ^ Nilsson S, Gustafsson JÅ (January 2011). "Estrogen receptors: therapies targeted to receptor subtypes". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 89 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1038/clpt.2010.226. PMID 21124311. S2CID 22724380.

- ^ Harris HA, Albert LM, Leathurby Y, Malamas MS, Mewshaw RE, Miller CP, et al. (October 2003). "Evaluation of an estrogen receptor-beta agonist in animal models of human disease". Endocrinology. 144 (10): 4241–4249. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0550. PMID 14500559.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas C, Gustafsson JÅ (2019). "Estrogen Receptor β and Breast Cancer". Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. pp. 309–342. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-99350-8_12. ISBN 978-3-319-99349-2. ISSN 2196-9906.

- ^ Dey P, Barros RP, Warner M, Ström A, Gustafsson JÅ (December 2013). "Insight into the mechanisms of action of estrogen receptor β in the breast, prostate, colon, and CNS". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 51 (3): T61–T74. doi:10.1530/JME-13-0150. PMID 24031087.

- ^ Song X, Pan ZZ (May 2012). "Estrogen receptor-beta agonist diarylpropionitrile counteracts the estrogenic activity of estrogen receptor-alpha agonist propylpyrazole-triol in the mammary gland of ovariectomized Sprague Dawley rats". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 130 (1–2): 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.018. PMID 22266284. S2CID 23865463.

- ^ a b c Song, X. (2014). Estrogen Receptor Beta Is A Negative Regulator Of Mammary Cell Proliferation. Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 259. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/259

- ^ Cheng G, Li Y, Omoto Y, Wang Y, Berg T, Nord M, et al. (January 2005). "Differential regulation of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta in primate mammary gland". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 90 (1): 435–444. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0861. PMID 15507513.

- ^ a b c Dall GV, Hawthorne S, Seyed-Razavi Y, Vieusseux J, Wu W, Gustafsson JA, et al. (June 2018). "Estrogen receptor subtypes dictate the proliferative nature of the mammary gland". The Journal of Endocrinology. 237 (3): 323–336. doi:10.1530/JOE-17-0582. PMID 29636363.

- ^ Hapangama DK, Kamal AM, Bulmer JN (Mar 2015). "Estrogen receptor β: the guardian of the endometrium". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (2): 174–193. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu053. PMID 25305176.

- ^ Couse JF, Lindzey J, Grandien K, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS (November 1997). "Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse". Endocrinology. 138 (11): 4613–4621. doi:10.1210/endo.138.11.5496. PMID 9348186.

- ^ Koehler KF, Helguero LA, Haldosén LA, Warner M, Gustafsson JA (May 2005). "Reflections on the discovery and significance of estrogen receptor beta". Endocrine Reviews. 26 (3): 465–478. doi:10.1210/er.2004-0027. PMID 15857973.

- ^ Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Watson PH, Murphy LC (August 1998). "Altered estrogen receptor alpha and beta messenger RNA expression during human breast tumorigenesis". Cancer Research. 58 (15): 3197–3201. PMID 9699641.

- ^ Reese JM, Suman VJ, Subramaniam M, Wu X, Negron V, Gingery A, et al. (October 2014). "ERβ1: characterization, prognosis, and evaluation of treatment strategies in ERα-positive and -negative breast cancer". BMC Cancer. 14 (749): 749. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-749. PMC 4196114. PMID 25288324.

- ^ Hawse JR, Carter JM, Aspros KG, Bruinsma ES, Koepplin JW, Negron V, et al. (January 2020). "Optimized immunohistochemical detection of estrogen receptor beta using two validated monoclonal antibodies confirms its expression in normal and malignant breast tissues". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 179 (1): 241–249. doi:10.1007/s10549-019-05441-3. PMC 6989344. PMID 31571071. S2CID 203609306.

- ^ Darabi M, Ani M, Panjehpour M, Rabbani M, Movahedian A, Zarean E (January–February 2011). "Effect of estrogen receptor β A1730G polymorphism on ABCA1 gene expression response to postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy". Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 15 (1–2): 11–15. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2010.0106. PMID 21117950.

- ^ Crider A, Thakkar R, Ahmed AO, Pillai A (9 September 2014). "Dysregulation of estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), aromatase (CYP19A1), and ER co-activators in the middle frontal gyrus of autism spectrum disorder subjects". Molecular Autism. 5 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/2040-2392-5-46. PMC 4161836. PMID 25221668.

- ^ Luo T, Kim JK (August 2016). "The Role of Estrogen and Estrogen Receptors on Cardiomyocytes: An Overview". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 32 (8): 1017–1025. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.10.021. PMC 4853290. PMID 26860777.

- ^ Muka T, Vargas KG, Jaspers L, Wen KX, Dhana K, Vitezova A, et al. (April 2016). "Estrogen receptor β actions in the female cardiovascular system: A systematic review of animal and human studies". Maturitas. 86: 28–43. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.01.009. PMID 26921926.

- ^ Li R, Cui J, Shen Y (May 2014). "Brain sex matters: estrogen in cognition and Alzheimer's disease". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 389 (1–2): 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.12.018. PMC 4040318. PMID 24418360.

- ^ Zhao L, Woody SK, Chhibber A (November 2015). "Estrogen receptor β in Alzheimer's disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics". Ageing Research Reviews. 24 (Pt B): 178–190. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.001. PMC 4661108. PMID 26307455.

- ^ Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Brown CM, Povroznik JM, Simpkins JW (October 2017). "Estrogens as neuroprotectants: Estrogenic actions in the context of cognitive aging and brain injury". Progress in Neurobiology. 157: 188–211. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.12.008. PMC 4985492. PMID 26891883.

- ^ Vargas KG, Milic J, Zaciragic A, Wen KX, Jaspers L, Nano J, et al. (November 2016). "The functions of estrogen receptor beta in the female brain: A systematic review". Maturitas. 93: 41–57. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.05.014. PMID 27338976.

- ^ Maria Kristina Parr; Piwen Zhao; Oliver Haupt; Sandrine Tchoukouegno Ngueu; Jonas Hengevoss; Karl Heinrich Fritzemeier; Marion Piechotta; Nils Schlörer; Peter Muhn; Wen-Ya Zheng; Ming-Yong Xie; Patrick Diel (2014). "Estrogen receptor beta is involved in skeletal muscle hypertrophy induced by the phytoecdysteroid ecdysterone". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 58 (9): 1861–1872. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201300806. PMID 24974955.

- ^ a b c d e f Hajirahimkhan A, Dietz BM, Bolton JL (May 2013). "Botanical modulation of menopausal symptoms: mechanisms of action?". Planta Medica. 79 (7): 538–553. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328187. PMC 3800090. PMID 23408273.

- ^ Minutolo F, Bertini S, Granchi C, Marchitiello T, Prota G, Rapposelli S, et al. (February 2009). "Structural evolutions of salicylaldoximes as selective agonists for estrogen receptor beta". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 52 (3): 858–867. doi:10.1021/jm801458t. PMID 19128016.

- ^ Barkhem T, Carlsson B, Nilsson Y, Enmark E, Gustafsson J, Nilsson S (July 1998). "Differential response of estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta to partial estrogen agonists/antagonists". Molecular Pharmacology. 54 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1124/mol.54.1.105. PMID 9658195.

- ^ Nakamura Y, Felizola SJ, Kurotaki Y, Fujishima F, McNamara KM, Suzuki T, et al. (May 2013). "Cyclin D1 (CCND1) expression is involved in estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) in human prostate cancer". The Prostate. 73 (6): 590–595. doi:10.1002/pros.22599. PMID 23060014. S2CID 39130053.

- ^ Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Hiroi H, Orimo A, Hosoi T, et al. (February 1998). "The complete primary structure of human estrogen receptor beta (hER beta) and its heterodimerization with ER alpha in vivo and in vitro". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 243 (1): 122–126. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7893. PMID 9473491.

- ^ a b Poelzl G, Kasai Y, Mochizuki N, Shaul PW, Brown M, Mendelsohn ME (March 2000). "Specific association of estrogen receptor beta with the cell cycle spindle assembly checkpoint protein, MAD2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (6): 2836–2839. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.2836P. doi:10.1073/pnas.050580997. PMC 16016. PMID 10706629.

- ^ Wong CW, Komm B, Cheskis BJ (June 2001). "Structure-function evaluation of ER alpha and beta interplay with SRC family coactivators. ER selective ligands". Biochemistry. 40 (23): 6756–6765. doi:10.1021/bi010379h. PMID 11389589.

- ^ Leo C, Li H, Chen JD (February 2000). "Differential mechanisms of nuclear receptor regulation by receptor-associated coactivator 3". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (8): 5976–5982. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.8.5976. PMID 10681591.

- ^ Lee SK, Jung SY, Kim YS, Na SY, Lee YC, Lee JW (February 2001). "Two distinct nuclear receptor-interaction domains and CREB-binding protein-dependent transactivation function of activating signal cointegrator-2". Molecular Endocrinology. 15 (2): 241–254. doi:10.1210/mend.15.2.0595. PMID 11158331.

- ^ Ko L, Cardona GR, Iwasaki T, Bramlett KS, Burris TP, Chin WW (January 2002). "Ser-884 adjacent to the LXXLL motif of coactivator TRBP defines selectivity for ERs and TRs". Molecular Endocrinology. 16 (1): 128–140. doi:10.1210/mend.16.1.0755. PMID 11773444.

- ^ Jung DJ, Na SY, Na DS, Lee JW (January 2002). "Molecular cloning and characterization of CAPER, a novel coactivator of activating protein-1 and estrogen receptors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (2): 1229–1234. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110417200. PMID 11704680.

- ^ Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, de Falco A, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, et al. (October 2000). "Steroid-induced androgen receptor-oestradiol receptor beta-Src complex triggers prostate cancer cell proliferation". The EMBO Journal. 19 (20): 5406–5417. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.20.5406. PMC 314017. PMID 11032808.

- ^ Slentz-Kesler K, Moore JT, Lombard M, Zhang J, Hollingsworth R, Weiner MP (October 2000). "Identification of the human Mnk2 gene (MKNK2) through protein interaction with estrogen receptor beta". Genomics. 69 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1006/geno.2000.6299. PMID 11013076.

Further reading

[edit]- Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA (2001). "Role of estrogen receptor beta in estrogen action". Annual Review of Physiology. 63: 165–192. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. PMID 11181953.

- Warner M, Saji S, Gustafsson JA (July 2000). "The normal and malignant mammary gland: a fresh look with ER beta onboard". Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 5 (3): 289–294. doi:10.1023/A:1009598828267. PMID 14973391. S2CID 34129981.

- Saxon LK, Turner CH (February 2005). "Estrogen receptor beta: the antimechanostat?". Bone. 36 (2): 185–192. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2004.08.003. PMID 15780944.

- Halachmi S, Marden E, Martin G, MacKay H, Abbondanza C, Brown M (June 1994). "Estrogen receptor-associated proteins: possible mediators of hormone-induced transcription". Science. 264 (5164): 1455–1458. Bibcode:1994Sci...264.1455H. doi:10.1126/science.8197458. PMID 8197458.

- Schwabe JW, Chapman L, Finch JT, Rhodes D (November 1993). "The crystal structure of the estrogen receptor DNA-binding domain bound to DNA: how receptors discriminate between their response elements". Cell. 75 (3): 567–578. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90390-C. PMID 8221895. S2CID 20795587.

- Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, et al. (August 1997). "Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300". Cell. 90 (3): 569–580. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80516-4. PMID 9267036. S2CID 15284825.

- Pace P, Taylor J, Suntharalingam S, Coombes RC, Ali S (October 1997). "Human estrogen receptor beta binds DNA in a manner similar to and dimerizes with estrogen receptor alpha". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (41): 25832–25838. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.41.25832. PMID 9325313.

- Brandenberger AW, Tee MK, Lee JY, Chao V, Jaffe RB (October 1997). "Tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha (ER-alpha) and beta (ER-beta) mRNA in the midgestational human fetus". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 82 (10): 3509–3512. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.10.4400. PMID 9329394.

- Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Fried G, et al. (December 1997). "Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 82 (12): 4258–4265. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. PMID 9398750.

- Vladusic EA, Hornby AE, Guerra-Vladusic FK, Lupu R (January 1998). "Expression of estrogen receptor beta messenger RNA variant in breast cancer". Cancer Research. 58 (2): 210–214. PMID 9443393.

- Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Hiroi H, Orimo A, Hosoi T, et al. (February 1998). "The complete primary structure of human estrogen receptor beta (hER beta) and its heterodimerization with ER alpha in vivo and in vitro". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 243 (1): 122–126. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7893. PMID 9473491.

- Alves SE, Lopez V, McEwen BS, Weiland NG (March 1998). "Differential colocalization of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) with oxytocin and vasopressin in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the female rat brain: an immunocytochemical study". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (6): 3281–3286. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.3281A. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3281. PMC 19733. PMID 9501254.

- Brandenberger AW, Tee MK, Jaffe RB (March 1998). "Estrogen receptor alpha (ER-alpha) and beta (ER-beta) mRNAs in normal ovary, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and ovarian cancer cell lines: down-regulation of ER-beta in neoplastic tissues". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 83 (3): 1025–1028. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.3.4788. PMID 9506768.

- Moore JT, McKee DD, Slentz-Kesler K, Moore LB, Jones SA, Horne EL, et al. (June 1998). "Cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor beta isoforms". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 247 (1): 75–78. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.8738. PMID 9636657.

- Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Orimo A, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Muramatsu M (August 1998). "Molecular cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor betacx: a potential inhibitor ofestrogen action in human". Nucleic Acids Research. 26 (15): 3505–3512. doi:10.1093/nar/26.15.3505. PMC 147730. PMID 9671811.

- Lu B, Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Murphy LJ, Murphy LC, Watson PH (March 1998). "Estrogen receptor-beta mRNA variants in human and murine tissues". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 138 (1–2): 199–203. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(98)00050-1. PMID 9685228. S2CID 54243493.

- Seol W, Hanstein B, Brown M, Moore DD (October 1998). "Inhibition of estrogen receptor action by the orphan receptor SHP (short heterodimer partner)". Molecular Endocrinology. 12 (10): 1551–1557. doi:10.1210/mend.12.10.0184. PMID 9773978.

- Hanstein B, Liu H, Yancisin MC, Brown M (January 1999). "Functional analysis of a novel estrogen receptor-beta isoform". Molecular Endocrinology. 13 (1): 129–137. doi:10.1210/mend.13.1.0234. PMID 9892018.

- Vidal O, Kindblom LG, Ohlsson C (June 1999). "Expression and localization of estrogen receptor-beta in murine and human bone". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 14 (6): 923–929. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.6.923. PMID 10352100. S2CID 85604096.

External links

[edit]- Estrogen+Receptor+beta at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q92731 (Estrogen receptor beta) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.