Dopamine receptor

Dopamine receptors are a class of G protein-coupled receptors that are prominent in the vertebrate central nervous system (CNS). The neurotransmitter dopamine is the primary endogenous ligand for dopamine receptors.

Dopamine receptors are implicated in many neurological processes, including motivation, pleasure, cognition, memory, learning, and fine motor control, as well as modulation of neuroendocrine signaling. Abnormal dopamine receptor signaling and dopaminergic nerve function is implicated in several neuropsychiatric disorders.[1] Thus, dopamine receptors are common neurologic drug targets; antipsychotics are often dopamine receptor antagonists while psychostimulants are typically indirect agonists of dopamine receptors.

Dopamine receptor subtypes

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

The existence of multiple types of receptors for dopamine was first proposed in 1976.[2][3] There are at least five subtypes of dopamine receptors, D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5. The D1 and D5 receptors are members of the D1-like family of dopamine receptors, whereas the D2, D3 and D4 receptors are members of the D2-like family. There is also some evidence that suggests the existence of possible D6 and D7 dopamine receptors, but such receptors have not been conclusively identified.[4]

At a global level, D1 receptors have widespread expression throughout the brain. Furthermore, D1-2 receptor subtypes are found at 10-100 times the levels of the D3-5 subtypes.[5]

D1-like family

Activation of D1-like family receptors is coupled to the G protein Gsα, which subsequently activates adenylyl cyclase, increasing the intracellular concentration of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).[citation needed]

- D1 is encoded by the Dopamine receptor D1 gene (DRD1).

- D5 is encoded by the Dopamine receptor D5 gene (DRD5).

D2-like family

Activation of D2-like family receptors is coupled to the G protein Giα, which directly inhibits the formation of cAMP by inhibiting the enzyme adenylyl cyclase.[6]

- D2 is encoded by the Dopamine receptor D2 gene (DRD2), of which there are two forms: D2Sh (short) and D2Lh (long):

- The D2Sh form is pre-synaptically situated, having modulatory functions (viz., autoreceptors, which regulate neurotransmission via feedback mechanisms. It affects synthesis, storage, and release of dopamine into the synaptic cleft).[7]

- The D2Lh form may function as a classical post-synaptic receptor, i.e., transmit information (in either an excitatory or an inhibitory fashion) unless blocked by a receptor antagonist or a synthetic partial agonist.[7]

- D3 is encoded by the Dopamine receptor D3 gene (DRD3). Maximum expression of dopamine D3 receptors is noted in the islands of Calleja and nucleus accumbens.[8]

- D4 is encoded by the Dopamine receptor D4 gene (DRD4). The D4 receptor gene displays polymorphisms that differ in a variable number tandem repeat present within the coding sequence of exon 3.[9] Some of these alleles are associated with greater incidence of certain disorders. For example, the D4.7 alleles have an established association with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.[10][11][12]

Receptor heteromers

Dopamine receptors have been shown to heterodimerize with a number of other G protein-coupled receptors.[13] The resulting dopamine receptor heterodimers include:[13]

- D1–adenosine A1

- D1–D2 dopamine receptor heteromer

- D1–D3 dopamine receptor heteromer

- D2–D4 dopamine receptor heteromer

- D2–adenosine A2A

- D2–ghrelin receptor

- D2sh–TAAR1 (an autoreceptor heterodimer)

- D4–adrenoceptor α1B

- D4–adrenoceptor β1

Role of dopamine receptors in the central nervous system

Dopamine receptors control neural signaling that modulates many important behaviors, such as spatial working memory.[14] Although dopamine receptors are widely distributed in the brain, different areas have different receptor types densities.[citation needed]

Non-CNS dopamine receptors

Cardio-pulmonary system

In humans, the pulmonary artery expresses D1, D2, D4, and D5 and receptor subtypes, which may account for vasodilatory effects of dopamine in the blood.[15] In rats, D1-like receptors are present on the smooth muscle of the blood vessels in most major organs.[16]

D4 receptors have been identified in the atria of rat and human hearts.[17] Dopamine increases myocardial contractility and cardiac output, without changing heart rate, by signaling through dopamine receptors.[4]

Renal system

Dopamine receptors are present along the nephron in the kidney, with proximal tubule epithelial cells showing the highest density.[16] In rats, D1-like receptors are present on the juxtaglomerular apparatus and on renal tubules, while D2-like receptors are present on the glomeruli, zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal cortex, renal tubules, and postganglionic sympathetic nerve terminals.[16] Dopamine signaling affects diuresis and natriuresis.[4]

Dopamine receptors in disease

Dysfunction of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the CNS has been implicated in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, including social phobia,[18] Tourette's syndrome,[19] Parkinson's disease,[20] schizophrenia,[19] neuroleptic malignant syndrome,[21] attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),[22] and drug and alcohol dependence.[19][23]

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Dopamine receptors have been recognized as important components in the etiology of ADHD for many years. Drugs used to treat ADHD, including methylphenidate and amphetamine, have significant effects on neuronal dopamine signaling. Studies of gene association have implicated several genes within dopamine signaling pathways; in particular, the D4.7 variant of D4 has been consistently shown to be more frequent in ADHD patients.[24] ADHD patients with the 4.7 allele also tend to have better cognitive performance and long-term outcomes compared to ADHD patients without the 4.7 allele, suggesting that the allele is associated with a more benign form of ADHD.[24]

The D4.7 allele has suppressed gene expression compared to other variants.[25]

Addictive drugs

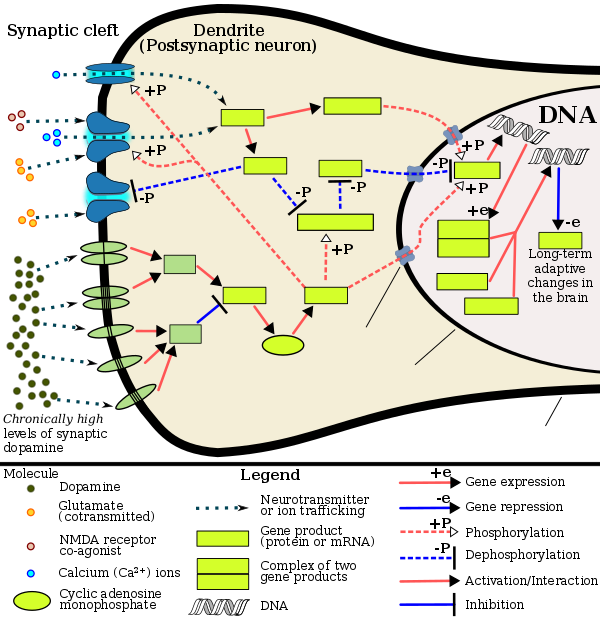

Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter involved in the reward pathway in the brain. Thus, drugs that increase dopamine signaling may produce euphoric effects. Many recreational drugs, such as cocaine and substituted amphetamines, inhibit the dopamine transporter (DAT), the protein responsible for removing dopamine from the neural synapse. When DAT activity is blocked, the synapse floods with dopamine and increases dopaminergic signaling. When this occurs, particularly in the nucleus accumbens,[26] increased D1[23] and decreased D2[26] receptor signaling mediates the "rewarding" stimulus of drug intake.[26]

Schizophrenia

While there is evidence that the dopamine system is involved in schizophrenia, the theory that hyperactive dopaminergic signal transduction induces the disease is controversial. Psychostimulants, such as amphetamine and cocaine, indirectly increase dopamine signaling; large doses and prolonged use can induce symptoms that resemble schizophrenia. Additionally, many antipsychotic drugs target dopamine receptors, especially D2 receptors.

Genetic hypertension

Dopamine receptor mutations can cause genetic hypertension in humans.[27] This can occur in animal models and humans with defective dopamine receptor activity, particularly D1.[16]

Dopamine regulation

Dopamine receptors are typically stable, however sharp (and sometimes prolonged) increases or decreases in dopamine levels can downregulate (reduce the numbers of) or upregulate (increase the numbers of) dopamine receptors. With stimulants, downregulation of DRD1 is typically associated with loss of interest in pleasureable activities, shortened attention span, and drug seeking behavior. With antipsychotics, associated D2-like receptor upregulation can cause temporary dyskinesia, or tardive dyskinesia (fine muscles e.g. facial muscles, twitch involuntarily).[medical citation needed]

Haloperidol, and some other antipsychotics, have been shown to increase the binding capacity of the D2 receptor when used over long periods of time (i.e. increasing the number of such receptors).[28] Haloperidol increased the number of binding sites by 98% above baseline in the worst cases, and yielded significant dyskinesia side effects.

Addictive stimuli have variable effects on dopamine receptors, depending on the particular stimulus.[29] According to one study,[30] cocaine, heroin, amphetamine, alcohol, and nicotine cause decreases in D2 receptor quantity. A similar association has been linked to food addiction, with a low availability of dopamine receptors present in people with greater food intake.[31][32] A recent news article[33] summarized a U.S. DOE Brookhaven National Laboratory study showing that increasing dopamine receptors with genetic therapy temporarily decreased cocaine consumption by up to 75%. The treatment was effective for 6 days. Cocaine upregulates D3 receptors in the nucleus accumbens, possibly contributing to drug seeking behavior.[34]

Certain stimulants will enhance cognition in the general population (e.g., direct or indirect mesocortical DRD1 agonists as a class), but only when used at low (therapeutic) concentrations.[35][36][37] Relatively high doses of dopaminergic stimulants will result in cognitive deficits.[36][37]

| dopamine receptor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | Dopamine receptorsReceptorsDopamine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | GeneCards: [2]; OMA:- orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Protein fosB, also known as FosB and G0/G1 switch regulatory protein 3 (G0S3), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (FOSB) gene.[38][39][40]

The FOS gene family consists of four members: FOS, FOSB, FOSL1, and FOSL2. These genes encode leucine zipper proteins that can dimerize with proteins of the JUN family (e.g., c-Jun, JunD), thereby forming the transcription factor complex AP-1. As such, the FOS proteins have been implicated as regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, and transformation.[38] FosB and its truncated splice variants, ΔFosB and further truncated Δ2ΔFosB, are all involved in osteosclerosis, although Δ2ΔFosB lacks a known transactivation domain, in turn preventing it from affecting transcription through the AP-1 complex.[41]

The ΔFosB splice variant has been identified as playing a central, crucial[42][43] role in the development and maintenance of addiction.[42][29][44] ΔFosB overexpression (i.e., an abnormally and excessively high level of ΔFosB expression which produces a pronounced gene-related phenotype) triggers the development of addiction-related neuroplasticity throughout the reward system and produces a behavioral phenotype that is characteristic of an addiction.[42][44][45] ΔFosB differs from the full length FosB and further truncated Δ2ΔFosB in its capacity to produce these effects, as only accumbal ΔFosB overexpression is associated with pathological responses to drugs.[46]

DeltaFosB

DeltaFosB – more commonly written as ΔFosB – is a truncated splice variant of the FOSB gene.[47] ΔFosB has been implicated as a critical factor in the development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions.[43][29][48] In the brain's reward system, it is linked to changes in a number of other gene products, such as CREB and sirtuins.[49][50][51] In the body, ΔFosB regulates the commitment of mesenchymal precursor cells to the adipocyte or osteoblast lineage.[52]

In the nucleus accumbens, ΔFosB functions as a "sustained molecular switch" and "master control protein" in the development of an addiction.[42][53][54] In other words, once "turned on" (sufficiently overexpressed) ΔFosB triggers a series of transcription events that ultimately produce an addictive state (i.e., compulsive reward-seeking involving a particular stimulus); this state is sustained for months after cessation of drug use due to the abnormal and exceptionally long half-life of ΔFosB isoforms.[42][53][54] ΔFosB expression in D1-type nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons directly and positively regulates drug self-administration and reward sensitization through positive reinforcement while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[42][44] Based upon the accumulated evidence, a medical review from late 2014 argued that accumbal ΔFosB expression can be used as an addiction biomarker and that the degree of accumbal ΔFosB induction by a drug is a metric for how addictive it is relative to others.[42]

Chronic administration of anandamide, or N-arachidonylethanolamide (AEA), an endogenous cannabinoid, and additives such as sucralose, a noncaloric sweetener used in many food products of daily intake, are found to induce an overexpression of ΔFosB in the infralimbic cortex (Cx), nucleus accumbens (NAc) core, shell, and central nucleus of amygdala (Amy), that induce long-term changes in the reward system.[55]

Role in addiction

| Addiction and dependence glossary[44][56][57] | |

|---|---|

| |

Chronic addictive drug use causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic projection, which arise through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms.[43][64][65] The most important transcription factors that produce these alterations are ΔFosB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).[43] ΔFosB is the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural adaptations and behavioral effects (e.g., expression-dependent increases in drug self-administration and reward sensitization) seen in drug addiction.[42][43][44] ΔFosB overexpression has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, propofol, and substituted amphetamines, among others.[42][43][64][66][67] ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in its expression.[43][44][68] Increases in nucleus accumbens ΔJunD expression (via viral vector-mediated gene transfer) or G9a expression (via pharmacological means) reduces, or with a large increase can even block, many of the neural and behavioral alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[45][43] Repression of c-Fos by ΔFosB, which consequently further induces expression of ΔFosB, forms a positive feedback loop that serves to indefinitely perpetuate the addictive state.

ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[43][48] Natural rewards, similar to drugs of abuse, induce gene expression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens, and chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological addictive state through ΔFosB overexpression.[43][29][48] Consequently, ΔFosB is the key mechanism involved in addictions to natural rewards (i.e., behavioral addictions) as well;[43][29][48] in particular, ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is critical for the reinforcing effects of sexual reward.[48] Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess bidirectional reward cross-sensitization effects[note 1] that are mediated through ΔFosB.[29][69] This phenomenon is notable since, in humans, a dopamine dysregulation syndrome, characterized by drug-induced compulsive engagement in natural rewards (specifically, sexual activity, shopping, and gambling), has also been observed in some individuals taking dopaminergic medications.[29]

ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs or treatments that oppose its action or reduce its expression) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.[70] Current medical reviews of research involving lab animals have identified a drug class – class I histone deacetylase inhibitors[note 2] – that indirectly inhibits the function and further increases in the expression of accumbal ΔFosB by inducing G9a expression in the nucleus accumbens after prolonged use.[45][68][71][72] These reviews and subsequent preliminary evidence which used oral administration or intraperitoneal administration of the sodium salt of butyric acid or other class I HDAC inhibitors for an extended period indicate that these drugs have efficacy in reducing addictive behavior in lab animals[note 3] that have developed addictions to ethanol, psychostimulants (i.e., amphetamine and cocaine), nicotine, and opiates;[68][72][73][74] however, as of August 2015[update], few clinical trials involving humans with addiction and any HDAC class I inhibitors have been conducted to test for treatment efficacy in humans or identify an optimal dosing regimen.[note 4]

Plasticity in cocaine addiction

ΔFosB accumulation from excessive drug use

Top: this depicts the initial effects of high dose exposure to an addictive drug on gene expression in the nucleus accumbens for various Fos family proteins (i.e., c-Fos, FosB, ΔFosB, Fra1, and Fra2).

Bottom: this illustrates the progressive increase in ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens following repeated twice daily drug binges, where these phosphorylated (35–37 kilodalton) ΔFosB isoforms persist in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens for up to 2 months.[54][62] |

ΔFosB levels have been found to increase upon the use of cocaine.[76] Each subsequent dose of cocaine continues to increase ΔFosB levels with no apparent ceiling of tolerance.[citation needed] Elevated levels of ΔFosB leads to increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, which in turn increases the number of dendritic branches and spines present on neurons involved with the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex areas of the brain. This change can be identified rather quickly, and may be sustained weeks after the last dose of the drug.

Transgenic mice exhibiting inducible expression of ΔFosB primarily in the nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum exhibit sensitized behavioural responses to cocaine.[77] They self-administer cocaine at lower doses than control,[78] but have a greater likelihood of relapse when the drug is withheld.[54][78] ΔFosB increases the expression of AMPA receptor subunit GluR2[77] and also decreases expression of dynorphin, thereby enhancing sensitivity to reward.[54]

| Target gene |

Target expression |

Neural effects | Behavioral effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Fos | ↓ | Molecular switch enabling the chronic induction of ΔFosB[note 5] |

– |

| dynorphin | ↓ [note 6] |

• Downregulation of κ-opioid feedback loop | • Diminished self-extinguishing response to drug |

| NF-κB | ↑ | • Expansion of Nacc dendritic processes • NF-κB inflammatory response in the NAcc • NF-κB inflammatory response in the CP |

• Increased drug reward • Locomotor sensitization |

| GluR2 | ↑ | • Decreased sensitivity to glutamate | • Increased drug reward |

| Cdk5 | ↑ | • GluR1 synaptic protein phosphorylation • Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes |

• Decreased drug reward (net effect) |

Summary of addiction-related plasticity

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity |

Type of reinforcer | Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse | Physical exercise (aerobic) |

Environmental enrichment | ||

| ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type MSNs |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [29] |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | [29] | |||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization |

Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | [29] |

| Psychostimulant self-administration |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [29] | |

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [29] |

| Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [29] | ||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

| CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [29] | |

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens |

No | Yes | No | Yes | [29] | ||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [29] | |

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | [29] |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin |

↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [29] | |

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [29] | |||

| Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [29] | |||

Other functions in the brain

Viral overexpression of ΔFosB in the output neurons of the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway (i.e., the medium spiny neurons in the dorsal striatum) induces levodopa-induced dyskinesias in animal models of Parkinson's disease.[79][80] Dorsal striatal ΔFosB is overexpressed in rodents and primates with dyskinesias;[80] postmortem studies of individuals with Parkinson's disease that were treated with levodopa have also observed similar dorsal striatal ΔFosB overexpression.[80] Levetiracetam, an antiepileptic drug, has been shown to dose-dependently decrease the induction of dorsal striatal ΔFosB expression in rats when co-administered with levodopa;[80] the signal transduction involved in this effect is unknown.[80]

ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens shell increases resilience to stress and is induced in this region by acute exposure to social defeat stress.[81][82][83]

Antipsychotic drugs have been shown to increase ΔFosB as well, more specifically in the prefrontal cortex. This increase has been found to be part of pathways for the negative side effects that such drugs produce.[84]

See also

Notes

- ^ In simplest terms, this means that when either amphetamine or sex is perceived as "more alluring or desirable" through reward sensitization, this effect occurs with the other as well.

- ^ Inhibitors of class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes are drugs that inhibit four specific histone-modifying enzymes: HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8. Most of the animal research with HDAC inhibitors has been conducted with four drugs: butyrate salts (mainly sodium butyrate), trichostatin A, valproic acid, and SAHA;[71][72] butyric acid is a naturally occurring short-chain fatty acid in humans, while the latter two compounds are FDA-approved drugs with medical indications unrelated to addiction.

- ^ Specifically, prolonged administration of a class I HDAC inhibitor appears to reduce an animal's motivation to acquire and use an addictive drug without affecting an animals motivation to attain other rewards (i.e., it does not appear to cause motivational anhedonia) and reduce the amount of the drug that is self-administered when it is readily available.[68][72][73]

- ^ Among the few clinical trials that employed a class I HDAC inhibitor, one utilized valproate for methamphetamine addiction.[75]

- ^ In other words, c-Fos repression allows ΔFosB to accumulate within nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons more rapidly because it is selectively induced in this state.[44]

- ^ ΔFosB has been implicated in causing both increases and decreases in dynorphin expression in different studies;[42][49] this table entry reflects only a decrease.

- Image legend

- ^ (Text color) Transcription factors

References

- ^ Girault JA, Greengard P (2004). "The neurobiology of dopamine signaling". Arch. Neurol. 61 (5): 641–4. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.5.641. PMID 15148138.

- ^ Cools AR, Van Rossum JM (1976). "Excitation-mediating and inhibition-mediating dopamine-receptors: a new concept towards a better understanding of electrophysiological, biochemical, pharmacological, functional and clinical data". Psychopharmacologia. 45 (3): 243–254. doi:10.1007/bf00421135. PMID 175391.

- ^ Ellenbroek BA, Homberg J, Verheij M, Spooren W, van den Bos R, Martens G (2014). "Alexander Rudolf Cools (1942-2013)". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 231 (11): 2219–2222. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3583-5. PMID 24770629.

- ^ a b c Contreras F, Fouillioux C, Bolívar A, Simonovis N, Hernández-Hernández R, Armas-Hernandez MJ, Velasco M (2002). "Dopamine, hypertension and obesity". J Hum Hypertens. 16 Suppl 1: S13–7. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001334. PMID 11986886.

- ^ Hurley MJ, Jenner P (2006). "What has been learnt from study of dopamine receptors in Parkinson's disease?". Pharmacol. Ther. 111 (3): 715–28. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.12.001. PMID 16458973.

- ^ Neves SR, Ram PT, Iyengar R (2002). "G protein pathways". Science. 296 (5573): 1636–9. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1636N. doi:10.1126/science.1071550. PMID 12040175.

- ^ a b [1]

- ^ Suzuki M, Hurd YL, Sokoloff P, Schwartz JC, Sedvall G (1998). "D3 dopamine receptor mRNA is widely expressed in the human brain". Brain Res. 779 (1–2): 58–74. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01078-0. PMID 9473588.

- ^ NCBI Database

- ^ Manor I, Tyano S, Eisenberg J, Bachner-Melman R, Kotler M, Ebstein RP (2002). "The short DRD4 repeats confer risk to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a family-based design and impair performance on a continuous performance test (TOVA)". Mol. Psychiatry. 7 (7): 790–4. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001078. PMID 12192625.

- ^ Langley K, Marshall L, van den Bree M, Thomas H, Owen M, O'Donovan M, Thapar A (2004). "Association of the dopamine D4 receptor gene 7-repeat allele with neuropsychological test performance of children with ADHD". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (1): 133–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.133. PMID 14702261.

- ^ Kustanovich V, Ishii J, Crawford L, Yang M, McGough JJ, McCracken JT, Smalley SL, Nelson SF (2004). "Transmission disequilibrium testing of dopamine-related candidate gene polymorphisms in ADHD: confirmation of association of ADHD with DRD4 and DRD5". Mol. Psychiatry. 9 (7): 711–7. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001466. PMID 14699430.

- ^ a b Beaulieu JM, Espinoza S, Gainetdinov RR (2015). "Dopamine receptors - IUPHAR Review 13". Br. J. Pharmacol. 172 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/bph.12906. PMC 4280963. PMID 25671228.

- ^ Williams GV, Castner SA (2006). "Under the curve: critical issues for elucidating D1 receptor function in working memory". Neuroscience. 139 (1): 263–76. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.028. PMID 16310964.

- ^ Ricci A, Mignini F, Tomassoni D, Amenta F (2006). "Dopamine receptor subtypes in the human pulmonary arterial tree". Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 26 (4): 361–9. doi:10.1111/j.1474-8673.2006.00376.x. PMID 16968475.

- ^ a b c d Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF (2003). "Renal dopamine receptors and hypertension". Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 228 (2): 134–42. PMID 12563019.

- ^ Ricci A, Bronzetti E, Fedele F, Ferrante F, Zaccheo D, Amenta F (1998). "Pharmacological characterization and autoradiographic localization of a putative dopamine D4 receptor in the heart". J Auton Pharmacol. 18 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2680.1998.1820115.x. PMID 9730266.

- ^ Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR, Abi-Dargham A, Zea-Ponce Y, Lin SH, Laruelle M (2000). "Low dopamine D(2) receptor binding potential in social phobia". Am J Psychiatry. 157 (3): 457–459. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.457. PMID 10698826.

- ^ a b c Kienast T, Heinz A (2006). "Dopamine and the diseased brain". CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 5 (1): 109–31. doi:10.2174/187152706784111560. PMID 16613557.

- ^ Fuxe K, Manger P, Genedani S, Agnati L (2006). "The nigrostriatal DA pathway and Parkinson's disease". J. Neural Transm. Suppl. Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementa. 70 (70): 71–83. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_13. ISBN 978-3-211-28927-3. PMID 17017512.

- ^ Mihara K, Kondo T, Suzuki A, Yasui-Furukori N, Ono S, Sano A, Koshiro K, Otani K, Kaneko S (2003). "Relationship between functional dopamine D2 and D3 receptors gene polymorphisms and neuroleptic malignant syndrome". Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 117B (1): 57–60. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10025. PMID 12555236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Faraone SV, Khan SA (2006). "Candidate gene studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 8: 13–20. PMID 16961425.

- ^ a b Hummel M, Unterwald EM (2002). "D1 dopamine receptor: a putative neurochemical and behavioral link to cocaine action". J. Cell. Physiol. 191 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1002/jcp.10078. PMID 11920678.

- ^ a b Gornick MC, Addington A, Shaw P, Bobb AJ, Sharp W, Greenstein D, Arepalli S, Castellanos FX, Rapoport JL (2007). "Association of the dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) gene 7-repeat allele with children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an update". Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 144B (3): 379–82. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30460. PMID 17171657.

- ^ Schoots O, Van Tol HH (2003). "The human dopamine D4 receptor repeat sequences modulate expression". Pharmacogenomics J. 3 (6): 343–8. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500208. PMID 14581929.

- ^ a b c Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, Lecca D (2004). "Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection". Neuropharmacology. 47 Suppl 1: 227–41. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. PMID 15464140.

- ^ Jose PA, Eisner GM, Felder RA (2003). "Regulation of blood pressure by dopamine receptors". Nephron Physiol. 95 (2): 19–27. doi:10.1159/000073676. PMID 14610323.

- ^ Silvestri S, Seeman MV, Negrete JC, Houle S, Shammi CM, Remington GJ, Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Wilson AA, Christensen BK, Seeman P (2000). "Increased dopamine D2 receptor binding after long-term treatment with antipsychotics in humans: a clinical PET study". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 152 (2): 174–80. doi:10.1007/s002130000532. PMID 11057521.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Cross-sensitization is also bidirectional, as a history of amphetamine administration facilitates sexual behavior and enhances the associated increase in NAc DA ... As described for food reward, sexual experience can also lead to activation of plasticity-related signaling cascades. The transcription factor delta FosB is increased in the NAc, PFC, dorsal striatum, and VTA following repeated sexual behavior (Wallace et al., 2008; Pitchers et al., 2010b). This natural increase in delta FosB or viral overexpression of delta FosB within the NAc modulates sexual performance, and NAc blockade of delta FosB attenuates this behavior (Hedges et al, 2009; Pitchers et al., 2010b). Further, viral overexpression of delta FosB enhances the conditioned place preference for an environment paired with sexual experience (Hedges et al., 2009). ... In some people, there is a transition from "normal" to compulsive engagement in natural rewards (such as food or sex), a condition that some have termed behavioral or non-drug addictions (Holden, 2001; Grant et al., 2006a). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al, 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008)."

Table 1" Cite error: The named reference "Natural and drug addictions" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Fehr C, Yakushev I, Hohmann N, Buchholz HG, Landvogt C, Deckers H, Eberhardt A, Kläger M, Smolka MN, Scheurich A, Dielentheis T, Schmidt LG, Rösch F, Bartenstein P, Gründer G, Schreckenberger M (2008). "Association of low striatal dopamine d2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse". Am J Psychiatry. 165 (4): 507–14. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020352. PMID 18316420.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Paul Park (2007-08-09). "Food Addiction: From Drugs to Donuts, Brain Activity May be the Key".

- ^ Paul M Johnson& Paul J Kenny (2010-03-28). "Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats". Nature Neuroscience Year published:(2010) doi:10.1038/nn.2519

- ^ "Gene Therapy For Addiction: Flooding Brain With 'Pleasure Chemical' Receptors Works On Cocaine, As On Alcohol". 2008-04-18.

- ^ Staley JK, Mash DC (1996). "Adaptive increase in D3 dopamine receptors in the brain reward circuits of human cocaine fatalities". J. Neurosci. 16 (19): 6100–6. PMID 8815892.

- ^ Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ (January 2015). "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". J. Cogn. Neurosci.: 1–21. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060.

The present meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the magnitude of the effects of methylphenidate and amphetamine on cognitive functions central to academic and occupational functioning, including inhibitory control, working memory, short-term episodic memory, and delayed episodic memory. In addition, we examined the evidence for publication bias. Forty-eight studies (total of 1,409 participants) were included in the analyses. We found evidence for small but significant stimulant enhancement effects on inhibitory control and short-term episodic memory. Small effects on working memory reached significance, based on one of our two analytical approaches. Effects on delayed episodic memory were medium in size. However, because the effects on long-term and working memory were qualified by evidence for publication bias, we conclude that the effect of amphetamine and methylphenidate on the examined facets of healthy cognition is probably modest overall. In some situations, a small advantage may be valuable, although it is also possible that healthy users resort to stimulants to enhance their energy and motivation more than their cognition. ... Earlier research has failed to distinguish whether stimulants' effects are small or whether they are nonexistent (Ilieva et al., 2013; Smith & Farah, 2011). The present findings supported generally small effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate on executive function and memory. Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ...

The results of this meta-analysis cannot address the important issues of individual differences in stimulant effects or the role of motivational enhancement in helping perform academic or occupational tasks. However, they do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size. - ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 318. ISBN 9780071481274.

Mild dopaminergic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. ...

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. Positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrates that methylphenidate decreases regional cerebral blood flow in the doroslateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex while improving performance of a spacial working memory task. This suggests that cortical networks that normally process spatial working memory become more efficient in response to the drug. ... [It] is now believed that dopamine and norepinephrine, but not serotonin, produce the beneficial effects of stimulants on working memory. At abused (relatively high) doses, stimulants can interfere with working memory and cognitive control ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacol. Rev. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMID 24344115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Entrez Gene: FOSB FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B".

- ^ Siderovski DP, Blum S, Forsdyke RE, Forsdyke DR (Oct 1990). "A set of human putative lymphocyte G0/G1 switch genes includes genes homologous to rodent cytokine and zinc finger protein-encoding genes". DNA and Cell Biology. 9 (8): 579–87. doi:10.1089/dna.1990.9.579. PMID 1702972.

- ^ Martin-Gallardo A, McCombie WR, Gocayne JD, FitzGerald MG, Wallace S, Lee BM, Lamerdin J, Trapp S, Kelley JM, Liu LI (Apr 1992). "Automated DNA sequencing and analysis of 106 kilobases from human chromosome 19q13.3". Nature Genetics. 1 (1): 34–9. doi:10.1038/ng0492-34. PMID 1301997. S2CID 1986255.

- ^ Sabatakos G, Rowe GC, Kveiborg M, Wu M, Neff L, Chiusaroli R, Philbrick WM, Baron R (May 2008). "Doubly truncated FosB isoform (Delta2DeltaFosB) induces osteosclerosis in transgenic mice and modulates expression and phosphorylation of Smads in osteoblasts independent of intrinsic AP-1 activity". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 23 (5): 584–95. doi:10.1359/jbmr.080110. PMC 2674536. PMID 18433296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ruffle JK (Nov 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–37. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

ΔFosB as a therapeutic biomarker

The strong correlation between chronic drug exposure and ΔFosB provides novel opportunities for targeted therapies in addiction (118), and suggests methods to analyze their efficacy (119). Over the past two decades, research has progressed from identifying ΔFosB induction to investigating its subsequent action (38). It is likely that ΔFosB research will now progress into a new era – the use of ΔFosB as a biomarker. If ΔFosB detection is indicative of chronic drug exposure (and is at least partly responsible for dependence of the substance), then its monitoring for therapeutic efficacy in interventional studies is a suitable biomarker (Figure 2). Examples of therapeutic avenues are discussed herein. ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). Some of these proposed interventions have limitations (125) or are in their infancy (75). However, it is hoped that some of these preliminary findings may lead to innovative treatments, which are much needed in addiction. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (Nov 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–37. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41 ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ a b c Biliński P, Wojtyła A, Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Chwedorowicz R, Cyranka M, Studziński T (2012). "Epigenetic regulation in drug addiction". Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 19 (3): 491–6. PMID 23020045.

For these reasons, ΔFosB is considered a primary and causative transcription factor in creating new neural connections in the reward centre, prefrontal cortex, and other regions of the limbic system. This is reflected in the increased, stable and long-lasting level of sensitivity to cocaine and other drugs, and tendency to relapse even after long periods of abstinence. These newly constructed networks function very efficiently via new pathways as soon as drugs of abuse are further taken ... In this way, the induction of CDK5 gene expression occurs together with suppression of the G9A gene coding for dimethyltransferase acting on the histone H3. A feedback mechanism can be observed in the regulation of these 2 crucial factors that determine the adaptive epigenetic response to cocaine. This depends on ΔFosB inhibiting G9a gene expression, i.e. H3K9me2 synthesis which in turn inhibits transcription factors for ΔFosB. For this reason, the observed hyper-expression of G9a, which ensures high levels of the dimethylated form of histone H3, eliminates the neuronal structural and plasticity effects caused by cocaine by means of this feedback which blocks ΔFosB transcription

- ^ Ohnishi YN, Ohnishi YH, Vialou V, Mouzon E, LaPlant Q, Nishi A, Nestler EJ (Jan 2015). "Functional role of the N-terminal domain of ΔFosB in response to stress and drugs of abuse". Neuroscience. 284: 165–70. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.10.002. PMC 4268105. PMID 25313003.

- ^ Nakabeppu Y, Nathans D (Feb 1991). "A naturally occurring truncated form of FosB that inhibits Fos/Jun transcriptional activity". Cell. 64 (4): 751–9. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90504-R. PMID 1900040. S2CID 23904956.

- ^ a b c d e Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M (2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958. PMID 22641964.

- ^ a b c Nestler EJ (Oct 2008). "Review. Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: role of DeltaFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–55. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure—cited earlier (Renthal et al. in press). The mechanism responsible for ΔFosB repression of c-fos expression is complex and is covered below. ...

Examples of validated targets for ΔFosB in nucleus accumbens ... GluR2 ... dynorphin ... Cdk5 ... NFκB ... c-Fos

Table 3 - ^ Renthal W, Nestler EJ (Aug 2008). "Epigenetic mechanisms in drug addiction". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 14 (8): 341–50. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.004. PMC 2753378. PMID 18635399.

- ^ Renthal W, Kumar A, Xiao G, Wilkinson M, Covington HE, Maze I, Sikder D, Robison AJ, LaPlant Q, Dietz DM, Russo SJ, Vialou V, Chakravarty S, Kodadek TJ, Stack A, Kabbaj M, Nestler EJ (May 2009). "Genome-wide analysis of chromatin regulation by cocaine reveals a role for sirtuins". Neuron. 62 (3): 335–48. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.026. PMC 2779727. PMID 19447090.

- ^ Sabatakos G, Sims NA, Chen J, Aoki K, Kelz MB, Amling M, Bouali Y, Mukhopadhyay K, Ford K, Nestler EJ, Baron R (Sep 2000). "Overexpression of DeltaFosB transcription factor(s) increases bone formation and inhibits adipogenesis". Nature Medicine. 6 (9): 985–90. doi:10.1038/79683. PMID 10973317. S2CID 20302360.

- ^ a b c d e Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ a b c d e Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW (Sep 2001). "DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (20): 11042–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811042N. doi:10.1073/pnas.191352698. PMC 58680. PMID 11572966.

- ^ Salaya-Velazquez NF, López-Muciño LA, Mejía-Chávez S, Sánchez-Aparicio P, Domínguez-Guadarrama AA, Venebra-Muñoz A (February 2020). "Anandamide and sucralose change ΔFosB expression in the reward system". NeuroReport. 31 (3): 240–244. doi:10.1097/WNR.0000000000001400. PMID 31923023. S2CID 210149592.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/wrenthal. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN (2015). "Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (2): 696–717 (Figure 1). doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8. PMC 4359351. PMID 24939695.

- ^ a b c d Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- ^ Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: Role of ΔFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–3255. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

- ^ a b Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 29: 565–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID 16776597.

- ^ Steiner H, Van Waes V (Jan 2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants". Progress in Neurobiology. 100: 60–80. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC 3525776. PMID 23085425.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (29 October 2014). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P (Feb 2009). "Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (8): 2915–20. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2915K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106. PMC 2650365. PMID 19202072.

- ^ a b c d Nestler EJ (January 2014). "Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B: 259–268. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. PMC 3766384. PMID 23643695.

Short-term increases in histone acetylation generally promote behavioral responses to the drugs, while sustained increases oppose cocaine's effects, based on the actions of systemic or intra-NAc administration of HDAC inhibitors. ... Genetic or pharmacological blockade of G9a in the NAc potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates, whereas increasing G9a function exerts the opposite effect (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). Such drug-induced downregulation of G9a and H3K9me2 also sensitizes animals to the deleterious effects of subsequent chronic stress (Covington et al., 2011). Downregulation of G9a increases the dendritic arborization of NAc neurons, and is associated with increased expression of numerous proteins implicated in synaptic function, which directly connects altered G9a/H3K9me2 in the synaptic plasticity associated with addiction (Maze et al., 2010).

G9a appears to be a critical control point for epigenetic regulation in NAc, as we know it functions in two negative feedback loops. It opposes the induction of ΔFosB, a long-lasting transcription factor important for drug addiction (Robison and Nestler, 2011), while ΔFosB in turn suppresses G9a expression (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). ... Also, G9a is induced in NAc upon prolonged HDAC inhibition, which explains the paradoxical attenuation of cocaine's behavioral effects seen under these conditions, as noted above (Kennedy et al., 2013). GABAA receptor subunit genes are among those that are controlled by this feedback loop. Thus, chronic cocaine, or prolonged HDAC inhibition, induces several GABAA receptor subunits in NAc, which is associated with increased frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). In striking contrast, combined exposure to cocaine and HDAC inhibition, which triggers the induction of G9a and increased global levels of H3K9me2, leads to blockade of GABAA receptor and IPSC regulation. - ^ Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (Feb 2013). "Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (8): 3434–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013. PMC 3865508. PMID 23426671.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and addictive disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 384–385. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b McCowan TJ, Dhasarathy A, Carvelli L (February 2015). "The Epigenetic Mechanisms of Amphetamine". J. Addict. Prev. 2015 (Suppl 1). PMC 4955852. PMID 27453897.

Epigenetic modifications caused by addictive drugs play an important role in neuronal plasticity and in drug-induced behavioral responses. Although few studies have investigated the effects of AMPH on gene regulation (Table 1), current data suggest that AMPH acts at multiple levels to alter histone/DNA interaction and to recruit transcription factors which ultimately cause repression of some genes and activation of other genes. Importantly, some studies have also correlated the epigenetic regulation induced by AMPH with the behavioral outcomes caused by this drug, suggesting therefore that epigenetics remodeling underlies the behavioral changes induced by AMPH. If this proves to be true, the use of specific drugs that inhibit histone acetylation, methylation or DNA methylation might be an important therapeutic alternative to prevent and/or reverse AMPH addiction and mitigate the side effects generate by AMPH when used to treat ADHD.

- ^ a b c d Walker DM, Cates HM, Heller EA, Nestler EJ (February 2015). "Regulation of chromatin states by drugs of abuse". Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30: 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.11.002. PMC 4293340. PMID 25486626.

Studies investigating general HDAC inhibition on behavioral outcomes have produced varying results but it seems that the effects are specific to the timing of exposure (either before, during or after exposure to drugs of abuse) as well as the length of exposure

- ^ a b Primary references involving sodium butyrate:

• Kennedy PJ, Feng J, Robison AJ, Maze I, Badimon A, Mouzon E, Chaudhury D, Damez-Werno DM, Haggarty SJ, Han MH, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Nestler EJ (April 2013). "Class I HDAC inhibition blocks cocaine-induced plasticity by targeted changes in histone methylation". Nat. Neurosci. 16 (4): 434–440. doi:10.1038/nn.3354. PMC 3609040. PMID 23475113.While acute HDAC inhibition enhances the behavioral effects of cocaine or amphetamine1,3,4,13,14, studies suggest that more chronic regimens block psychostimulant-induced plasticity3,5,11,12. ... The effects of pharmacological inhibition of HDACs on psychostimulant-induced plasticity appear to depend on the timecourse of HDAC inhibition. Studies employing co-administration procedures in which inhibitors are given acutely, just prior to psychostimulant administration, report heightened behavioral responses to the drug1,3,4,13,14. In contrast, experimental paradigms like the one employed here, in which HDAC inhibitors are administered more chronically, for several days prior to psychostimulant exposure, show inhibited expression3 or decreased acquisition of behavioral adaptations to drug5,11,12. The clustering of seemingly discrepant results based on experimental methodologies is interesting in light of our present findings. Both HDAC inhibitors and psychostimulants increase global levels of histone acetylation in NAc. Thus, when co-administered acutely, these drugs may have synergistic effects, leading to heightened transcriptional activation of psychostimulant-regulated target genes. In contrast, when a psychostimulant is given in the context of prolonged, HDAC inhibitor-induced hyperacetylation, homeostatic processes may direct AcH3 binding to the promoters of genes (e.g., G9a) responsible for inducing chromatin condensation and gene repression (e.g., via H3K9me2) in order to dampen already heightened transcriptional activation. Our present findings thus demonstrate clear cross talk among histone PTMs and suggest that decreased behavioral sensitivity to psychostimulants following prolonged HDAC inhibition might be mediated through decreased activity of HDAC1 at H3K9 KMT promoters and subsequent increases in H3K9me2 and gene repression.

• Simon-O'Brien E, Alaux-Cantin S, Warnault V, Buttolo R, Naassila M, Vilpoux C (July 2015). "The histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate decreases excessive ethanol intake in dependent animals". Addict Biol. 20 (4): 676–689. doi:10.1111/adb.12161. PMID 25041570. S2CID 28667144.Altogether, our results clearly demonstrated the efficacy of NaB in preventing excessive ethanol intake and relapse and support the hypothesis that HDACi may have a potential use in alcohol addiction treatment.

• Castino MR, Cornish JL, Clemens KJ (April 2015). "Inhibition of histone deacetylases facilitates extinction and attenuates reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0124796. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1024796C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124796. PMC 4399837. PMID 25880762.treatment with NaB significantly attenuated nicotine and nicotine + cue reinstatement when administered immediately ... These results provide the first demonstration that HDAC inhibition facilitates the extinction of responding for an intravenously self-administered drug of abuse and further highlight the potential of HDAC inhibitors in the treatment of drug addiction.

- ^ Kyzar EJ, Pandey SC (August 2015). "Molecular mechanisms of synaptic remodeling in alcoholism". Neurosci. Lett. 601: 11–9. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.051. PMC 4506731. PMID 25623036.

Increased HDAC2 expression decreases the expression of genes important for the maintenance of dendritic spine density such as BDNF, Arc, and NPY, leading to increased anxiety and alcohol-seeking behavior. Decreasing HDAC2 reverses both the molecular and behavioral consequences of alcohol addiction, thus implicating this enzyme as a potential treatment target (Fig. 3). HDAC2 is also crucial for the induction and maintenance of structural synaptic plasticity in other neurological domains such as memory formation [115]. Taken together, these findings underscore the potential usefulness of HDAC inhibition in treating alcohol use disorders ... Given the ability of HDAC inhibitors to potently modulate the synaptic plasticity of learning and memory [118], these drugs hold potential as treatment for substance abuse-related disorders. ... Our lab and others have published extensively on the ability of HDAC inhibitors to reverse the gene expression deficits caused by multiple models of alcoholism and alcohol abuse, the results of which were discussed above [25,112,113]. This data supports further examination of histone modifying agents as potential therapeutic drugs in the treatment of alcohol addiction ... Future studies should continue to elucidate the specific epigenetic mechanisms underlying compulsive alcohol use and alcoholism, as this is likely to provide new molecular targets for clinical intervention.

- ^ Kheirabadi GR, Ghavami M, Maracy MR, Salehi M, Sharbafchi MR (2016). "Effect of add-on valproate on craving in methamphetamine depended patients: A randomized trial". Advanced Biomedical Research. 5: 149. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.187404. PMC 5025910. PMID 27656618.

- ^ Hope BT (May 1998). "Cocaine and the AP-1 transcription factor complex". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 844 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:1998NYASA.844....1H. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08216.x. PMID 9668659. S2CID 11683570.

- ^ a b Kelz MB, Chen J, Carlezon WA, Whisler K, Gilden L, Beckmann AM, Steffen C, Zhang YJ, Marotti L, Self DW, Tkatch T, Baranauskas G, Surmeier DJ, Neve RL, Duman RS, Picciotto MR, Nestler EJ (Sep 1999). "Expression of the transcription factor deltaFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine". Nature. 401 (6750): 272–6. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..272K. doi:10.1038/45790. PMID 10499584. S2CID 4390717.

- ^ a b Colby CR, Whisler K, Steffen C, Nestler EJ, Self DW (Mar 2003). "Striatal cell type-specific overexpression of DeltaFosB enhances incentive for cocaine". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (6): 2488–93. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02488.2003. PMC 6742034. PMID 12657709.

- ^ Cao X, Yasuda T, Uthayathas S, Watts RL, Mouradian MM, Mochizuki H, Papa SM (May 2010). "Striatal overexpression of DeltaFosB reproduces chronic levodopa-induced involuntary movements". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (21): 7335–43. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0252-10.2010. PMC 2888489. PMID 20505100.

- ^ a b c d e Du H, Nie S, Chen G, Ma K, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Papa SM, Cao X (2015). "Levetiracetam Ameliorates L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in Hemiparkinsonian Rats Inducing Critical Molecular Changes in the Striatum". Parkinson's Disease. 2015: 253878. doi:10.1155/2015/253878. PMC 4322303. PMID 25692070.

Furthermore, the transgenic overexpression of ΔFosB reproduces AIMs in hemiparkinsonian rats without chronic exposure to L-DOPA [13]. ... FosB/ΔFosB immunoreactive neurons increased in the dorsolateral part of the striatum on the lesion side with the used antibody that recognizes all members of the FosB family. All doses of levetiracetam decreased the number of FosB/ΔFosB positive cells (from 88.7 ± 1.7/section in the control group to 65.7 ± 0.87, 42.3 ± 1.88, and 25.7 ± 1.2/section in the 15, 30, and 60 mg groups, resp.; Figure 2). These results indicate dose-dependent effects of levetiracetam on FosB/ΔFosB expression. ... In addition, transcription factors expressed with chronic events such as ΔFosB (a truncated splice variant of FosB) are overexpressed in the striatum of rodents and primates with dyskinesias [9, 10]. ... Furthermore, ΔFosB overexpression has been observed in postmortem striatal studies of Parkinsonian patients chronically treated with L-DOPA [26]. ... Of note, the most prominent effect of levetiracetam was the reduction of ΔFosB expression, which cannot be explained by any of its known actions on vesicular protein or ion channels. Therefore, the exact mechanism(s) underlying the antiepileptic effects of levetiracetam remains uncertain.

- ^ "ROLE OF ΔFOSB IN THE NUCLEUS ACCUMBENS". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. NESTLER LAB: LABORATORY OF MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Furuyashiki T, Deguchi Y (Aug 2012). "[Roles of altered striatal function in major depression]". Brain and Nerve = Shinkei Kenkyū No Shinpo (in Japanese). 64 (8): 919–26. PMID 22868883.

- ^ Nestler EJ (Apr 2015). "∆FosB: a transcriptional regulator of stress and antidepressant responses". European Journal of Pharmacology. 753: 66–72. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.10.034. PMC 4380559. PMID 25446562.

In more recent years, prolonged induction of ∆FosB has also been observed within NAc in response to chronic administration of certain forms of stress. Increasing evidence indicates that this induction represents a positive, homeostatic adaptation to chronic stress, since overexpression of ∆FosB in this brain region promotes resilience to stress, whereas blockade of its activity promotes stress susceptibility. Chronic administration of several antidepressant medications also induces ∆FosB in the NAc, and this induction is required for the therapeutic-like actions of these drugs in mouse models. Validation of these rodent findings is the demonstration that depressed humans, examined at autopsy, display reduced levels of ∆FosB within the NAc. As a transcription factor, ΔFosB produces this behavioral phenotype by regulating the expression of specific target genes, which are under current investigation. These studies of ΔFosB are providing new insight into the molecular basis of depression and antidepressant action, which is defining a host of new targets for possible therapeutic development.

- ^ Dietz DM, Kennedy PJ, Sun H, Maze I, Gancarz AM, Vialou V, Koo JW, Mouzon E, Ghose S, Tamminga CA, Nestler EJ (February 2014). "ΔFosB induction in prefrontal cortex by antipsychotic drugs is associated with negative behavioral outcomes". Neuropsychopharmacology. 39 (3): 538–44. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.255. PMC 3895248. PMID 24067299.

Further reading

- Schuermann M, Jooss K, Müller R (Apr 1991). "fosB is a transforming gene encoding a transcriptional activator". Oncogene. 6 (4): 567–76. PMID 1903195.

- Brown JR, Ye H, Bronson RT, Dikkes P, Greenberg ME (Jul 1996). "A defect in nurturing in mice lacking the immediate early gene fosB". Cell. 86 (2): 297–309. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80101-4. PMID 8706134. S2CID 17266171.

- Heximer SP, Cristillo AD, Russell L, Forsdyke DR (Dec 1996). "Sequence analysis and expression in cultured lymphocytes of the human FOSB gene (G0S3)". DNA and Cell Biology. 15 (12): 1025–38. doi:10.1089/dna.1996.15.1025. PMID 8985116.

- Liberati NT, Datto MB, Frederick JP, Shen X, Wong C, Rougier-Chapman EM, Wang XF (Apr 1999). "Smads bind directly to the Jun family of AP-1 transcription factors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (9): 4844–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.4844L. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.4844. PMC 21779. PMID 10220381.

- Yamamura Y, Hua X, Bergelson S, Lodish HF (Nov 2000). "Critical role of Smads and AP-1 complex in transforming growth factor-beta -dependent apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (46): 36295–302. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006023200. PMID 10942775.

- Bergman MR, Cheng S, Honbo N, Piacentini L, Karliner JS, Lovett DH (Feb 2003). "A functional activating protein 1 (AP-1) site regulates matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) transcription by cardiac cells through interactions with JunB-Fra1 and JunB-FosB heterodimers". Biochemical Journal. 369 (Pt 3): 485–96. doi:10.1042/BJ20020707. PMC 1223099. PMID 12371906.

- Milde-Langosch K, Kappes H, Riethdorf S, Löning T, Bamberger AM (Feb 2003). "FosB is highly expressed in normal mammary epithelia, but down-regulated in poorly differentiated breast carcinomas". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 77 (3): 265–75. doi:10.1023/A:1021887100216. PMID 12602926. S2CID 987857.

- Baumann S, Hess J, Eichhorst ST, Krueger A, Angel P, Krammer PH, Kirchhoff S (Mar 2003). "An unexpected role for FosB in activation-induced cell death of T cells". Oncogene. 22 (9): 1333–9. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206126. PMID 12618758. S2CID 10696422.

- Holmes DI, Zachary I (Jan 2004). "Placental growth factor induces FosB and c-Fos gene expression via Flt-1 receptors". FEBS Letters. 557 (1–3): 93–8. Bibcode:2004FEBSL.557...93H. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01452-2. PMID 14741347. S2CID 6596900.

- Konsman JP, Blomqvist A (May 2005). "Forebrain patterns of c-Fos and FosB induction during cancer-associated anorexia-cachexia in rat". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (10): 2752–66. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04102.x. PMID 15926923. S2CID 40045788.

External links

- ROLE OF ΔFOSB IN THE NUCLEUS ACCUMBENS Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- KEGG Pathway – human alcohol addiction

- KEGG Pathway – human amphetamine addiction

- KEGG Pathway – human cocaine addiction

- FOSB+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

See also

- D2 short (presynaptic)

- Category:Dopamine agonists

- Category:Dopamine antagonists

External links

- "Dopamine Receptors". IUPHAR Database of Receptors and Ion Channels. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.

- Zimmerberg, B., "Dopamine receptors: A representative family of metabotropic receptors, Multimedia Neuroscience Education Project (2002)

- Scholarpedia article on Dopamine anatomy